Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Athens in Jerusalem

Athens in Jerusalem

Uploaded by

Ben FortisCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Athens in Jerusalem

Athens in Jerusalem

Uploaded by

Ben FortisCopyright:

Available Formats

ATHENS IN JERUSALEM.

ON THE DEFINITION OF JEWISH PHILOSOPHY

The question what Jewish philosophy is and why this field is important

for the academic study of philosophy has often been a subject of debate.

The academic study of Jewish philosophy started in the middle of the

nineteenth century with the pioneering work of Manuel Joel and

Salomon Munk. It was the early period of die Wissenschaft des

Judentums. Since these early years in the academic study of Jewish philos-

ophers, scholars have debated on what is Jewish and what is philosoph-

ical in Jewish philosophy. This discussion focuses on questions like: is

Jewish philosophy a philosophy of Judaism, is it a specifically Jewish

contribution to the debate on philosophical problems, is it a part of

philosophy of religion or is it broader, is it philosophizing by Jews, is

there really such a thing as Jewish philosophy, is the term not an internal

contradiction?

In reply to these questions some scholars argue that philosophy

entered Judaism as an external influence which is not essentially typical

of Judaism. Julius Guttmann, for instance, opens his standard work Die

Philosophie des Judentums from 1933 with the claim that the Jewish

people did not arrive at philosophical thought by its own efforts, but

received philosophy externally. He believes that the history of Jewish

philosophy is the history of the reception of an alien body of thought,

which was then merged into Jewish thought. I Eliezer Schweid and

Aviezer Ravitzky also state that Jewish philosophy is the result of

external influences. According to Ravitzky, as long as Jewish thought

remains within what he calls the framework of the rabbinic tradition,

regardless of the era, no attempt is undertaken to formulate it in univer-

sally valid terms. The internal certainty of the particular tradition is suffi-

cient. Jewish philosophy only develops in confrontation with the outside

world, as in the Hellenistic period in Alexandria, in the Iberian peninsula

I J. Guttmann, Die Philosophie desJudentums, Munchen 1933, 9. In the revised and ex-

panded Hebrew version of this book, Ha-philosophia shel ha-yahadut Uerusalem 1951)

and in its English translation, Philosophies of Judaism (New York 1964) Guttmann's posi-

tion is unchanged.

S. Berger, M. Brocke and 1. Zwiep (eds.), Zutot 2.001, I07-III.

1°7

Downloaded from Brill.com01/17/2020 08:47:28PM

via FU Berlin

ZUTOT 2001 - JEWISH THOUGHT

in the Middle Ages, in Italy during the Renaissance, in Germany in the

modern era. Schweid adds that Jewish philosophy in the Middle Ages

lags behind developments in non-Jewish philosophy, because it is the

result of external influences, and so is anachronistic.'

This description of the matter is problematic. Against Schweid's

statement about the anachronistic character of Jewish philosophy, I

mention only Mendelssohn's innovative contribution to contemporary

philosophy and his original discussion of Judaism within the framework

of Enlightenment thought, and the innovative aspect of Hermann

Cohen's concept of Judaism in the context of his critical discussion of

Kant's legacy. Other examples are easily found, for instance Levinas.

They show that Schweid's claim, if in fact it applies to the Middle Ages, is

not valid in the modern era.

Second, the claim that philosophy is essentially alien to Judaism

reflects an essentialism which is hard to prove. It is true that Jewish

philosophy developed in the Diaspora, and that Judaism in Palestine

during the First and Second Temple Period does not have philosophers

like the pre-Socratics, Plato, or Aristotle. But these facts do not warrant

the conclusion that philosophy is essentially alien to Judaism (Guttman,

Schweid), nor that Jewish thought does not need philosophy as long as it

remains within the framework of the rabbinic tradition (Ravitzky). Such

a claim confuses inception with essence, and forgets that rabbinic

thought in Antiquity did not develop in a vacuum. Rabbinic thought in

Antiquity, too, shows Greek and other influences which made construc-

tive contributions to it.3 The germination and flowering of Jewish philos-

ophy can also be interpreted as the rise and development of something

that was already present, potentially or essentially. Ravitzky's claim that

rabbinic thought does not need philosophy as long as it remians within its

own domain seems at odds with the Talmud's words on what we can call

the architecture of knowledge. The passage in question reads: 'Raba said,

2 A. Ravitzky, History and Faith. Studies in Jewish philosophy. Amsterdam Studies in

Jewish Thought 2, Amsterdam 1996, 4f.; E. Sehweid, Toledot ha-philosophia ha-yehudit

mi-Rasag 'ad Rambam, Jerusalem 1970, 3ff.

1 See, among others, Ph. Alexander, '"Quid Athenis et Hierosolymis?" Rabbinic Mid-

rash and Hermeneutics in the Graeeo-Roman World', in P.R. Davies, R.T. Write, eds, A

Tribute to Geza Vermes. Essays on Jewish and Christian Literature and History, Sheffield

1990, 101-124. There are many reference books in this field, such as The Cambridge His-

tory of Judaism, vol. 2, ed. by W:D. Davies and L. Finkelstein, Cambridge 1989.

108

Downloaded from Brill.com01/17/2020 08:47:28PM

via FU Berlin

ATHENS IN JERUSALEM

when a man is led to judgement [in the next world], he will be asked: did

you understand one thing from the other, havanat davar mi-tokh davar'.

Rashi says of this last question: to understand one thing from the other is

knowledge, da'at.4 The principle of understanding one thing from the

other corresponds to what, for brevity's sake and in general terms, I call

the analytical method or the principle of deduction. So this passage illus-

trates the important place which the analytical method for acquiring

knowledge occupies in (traditional) rabbinic Judaism: one of the six

questions which you will be asked in the next world is whether you have

acquired knowledge by means of the deductive principle. The passage

also illustrates that, at the very least, a methodological affinity can be

observed between rabbinic thought and philosophy. And this observation

renders problematic the statement that rabbinic thought does not need

philosophy. In addition, the statement shows a striking contrast with

Maimonides' assertion in Mishneh Torah that study of the Torah not only

includes oral and written doctrine but also logic, hermeneutical princi-

ples for the interpretation of the Torah, physics, and metaphysics.5

To press home my objection I follow Zev Harvey in referring to a

Greek philosopher who lived shortly after Alexander the Great.

Theophrastus of Eresus, a pupil of Plato and Aristotle, was head of the

Peripatetic School after Aristotle's death. In his work Peri Eusebeias,

which has been passed down in fragments, Theophrastus includes a

description of the sacrificial rites of the Jews, and in passing remarks that

Jews are philosophoi to genos, philosophers by nature, who spend all day

discussing the deity, and at night study the stars and say prayers.6

According to this ancient fragment of text, which comes from Athens and

not from Jerusalem, philosophy is not alien to Jews and Judaism.

4 bT Shabo 3 Ta, and Rashi ad loc.: havanat davar mi-tokh davar haynu da'at.

\ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Talmud Torah i.II and Hilchot Yesode ha-To-

rah iv.13; Moreh ha-Nevukhim iii,51, ed. Y. Kapach, 3 vols, Jerusalem 1972., 674£.; The

Guide of the Perplexed, trans/. S. Pines, Chicago 1963,619.

6 See fragment 2.6.1 of Peri Eusebeias, in Theophrastus of Eresus. Sources for his Life,

Writings, Thought, and Influence, ed. and trans/. by W.W. Fortenbaugh e.a., Leiden 1993"

vo/. 2., 42.2. See also W.Z. Harvey, 'Sa'adiah, Mendelssohn, and the Theophrastus Thesis:

Paradigms of Jewish Enlightenment. A Response to Raphael Jospe', in R. Jospe, ed., Para-

digms in Jewish Philosophy, Cranbury 1997,60-69.

109

Downloaded from Brill.com01/17/2020 08:47:28PM

via FU Berlin

ZUTOT 2001 - JEWISH THOUGHT

What do Athens and Jerusalem have in common?? Unlike Tertullian,

who was one of the first to ask this question, Jewish philosophy sees

Athens and Jerusalem as symbols of Greek and Jewish thought. The two

are often presented as each other's opposites. There is a great deal of

debate in modern Jewish philosophy on the status of Jerusalem, and on

what Athens and Jerusalem have in common. My position in this discus-

sion is that it is wrong to see Athens and Jerusalem as essentially opposed.

Instead, we do better to characterize the field of study as Athens in

Jerusalem and Jerusalem in Athens. In Jewish philosophy Athens is an

essential and integral part of Jerusalem, and Jerusalem of Athens.

Jewish philosophy is, first of all, the critical articulation of Jewish

culture, that is, its heritage and modes of actual manifestation. I use the

terms critique and critical here in the classic sense of 'giving account of',

as we find in, e.g., in Plato and Kant. As a critique of Jewish culture,

Jewish philosophy is part, indeed, of philosophy proper. The exposition

and evaluation of Jewish culture is an attempt to give an account of the

Jewish ways of life and ways of thinking in all their varieties throughout

the ages. And the 'tribune' before which Judaism is evaluated is that of

reason. This definition is a knowing wink to the Golden Age of reason in

German-Jewish philosophy, as it commenced with Moses Mendelssohn

and found its culmination and its temporary closure in Hermann Cohen.

Mendelssohn, Samuel Hirsch, Salomon Formstecher, Salomon Stein-

heim, Nachman Krochmal, Manuel Joel, Cohen, and their contempo-

raries, attempted to offer a critical account of Judaism according to

contemporary philosophical standards and terminology. This critique

was aimed at elucidating both the Jewish value and the philosophical

validity of Jewish philosophy. After Cohen German-Jewish philosophy

shifted away from its critical idealistic foundation. Franz Rosenzweig

and other dialogicists distanced themselves from the reliable and rigorous

tradition of critical idealism and, remarkably, reverted to a pre-critical

kind of thinking with its supposed duality of thought and perception,

inner and outer world, reason and revelation, and the primacy of

language over thought.

The question of giving account in terms of reason is what Athens and

Jerusalem have in common. In Mendelssohn and in Cohen, for instance,

7 Cf. Tertullian, De prescrlptlOne haereticorum, vn.9: Quid ergo Athenis et

Hierosolymis. Tertulliani opera, pars I, Turnholti 1954,193.

110

Downloaded from Brill.com01/17/2020 08:47:28PM

via FU Berlin

ATHENS IN JERUSALEM

this part of their philosophy is focused on the exposition of the Jewish

tradition in the context of the religion of reason. But Judaism is obviously

more than religion, Jewish culture is more comprehensive than the

rabbinic tradition. And so, generally speaking, this part of Jewish philos-

ophy involves more than the clarification of this tradition.

In the second place Jewish philosophy includes the contribution to

contemporary philosophy, 'Jerusalem in Athens'. In Mendelssohn this

contribution includes the Phiidon, the Morgenstunden, the discussion of

the separation of Church and State in his Jerusalem, and Mendelssohn's

criticism of what Lessing and others saw as the necessary connection

between Enlightenment thought and Christianity. This criticism emerges

from the discussion between Mendelssohn and Lessing on the concept of

Lessing's Das Christentum der Vernunft, on which Lessing had been

working since 1751-3 and on which he apparently debated with

Mendelssohn at the beginning (1754) of their friendship,8 and from the

discussion between Mendelssohn and Lavater. In Hermann Cohen this

part involves for instance his view of the connection between Judaism

and socialism, or his criticism of Kant's separation of law and morality.

Finally, the observations which I have made above on the nature of

our field of studies and the various problems that are related to its defini-

tion are based on the presupposition that Jewish philosophy is part of

philosophy proper and, consequently, moves along with the trends and

developments of philosophy.

Reinier Munk

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

8 According to Mendelssohn's Morgenstunden, GS II, 369 (JubA III.2) 133, and An die

Freunde Lessings (1786), GS III, 6 (JubA lIb 189) Mendelssohn and Lessing discussed (a

draft version of) Das Christentum der Vernunft in the early years of their friendeship, which

took a start in 1754. Mendelssohn and Lessing both refer to this discussion in their corre-

spondence; d. Mendelssohn's letter to Lessing of February 1st In4, and Lessing's to Men-

delssohn d.d. May 1st 1774, in GS V 192-193 194-195 (JubA XII.2, 39-41,46-47). See also

A. Altmann, Moses Mende/ssohns Friihschriften zur Metaphysik, Tiibingen 1969, 2ooff.

III

Downloaded from Brill.com01/17/2020 08:47:28PM

via FU Berlin

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Pirkey AvotDocument125 pagesPirkey AvotPeter Novak100% (3)

- 3000 Years of JUDAISM and JerusalemDocument4 pages3000 Years of JUDAISM and JerusalemJan Erl Angelo RosalNo ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Pesachim 47: Lechem HapanimDocument32 pagesDaf Ditty Pesachim 47: Lechem HapanimJulian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- CAS Myths and FactsDocument48 pagesCAS Myths and FactsJohn Bowen BrownNo ratings yet

- Starting Guide and ContentsDocument3 pagesStarting Guide and Contentspeludo4856No ratings yet

- 1 STDocument1 page1 ST4TorahNo ratings yet

- Holocaust Analogies: Repaying The Mortgage: by Tony Greenstein, in RETURN, March 1990Document11 pagesHolocaust Analogies: Repaying The Mortgage: by Tony Greenstein, in RETURN, March 1990SFLDNo ratings yet

- Illuminating The Light of Chanukah: Bayamim Hahem Bazman HazehDocument3 pagesIlluminating The Light of Chanukah: Bayamim Hahem Bazman Hazehoutdash2No ratings yet

- Pharisees, Sadducees & EssenesDocument2 pagesPharisees, Sadducees & EssenesWilliam .williamsNo ratings yet

- Reflection of The Books of TanakDocument2 pagesReflection of The Books of TanakKyle AmatosNo ratings yet

- Maimonides - Melachim UMilchamotDocument41 pagesMaimonides - Melachim UMilchamotst iNo ratings yet

- Ashkenazi Names - The Etymology of The Most Common Jewish SurnamesDocument7 pagesAshkenazi Names - The Etymology of The Most Common Jewish SurnamesJarmitage123No ratings yet

- Yoel RosenfeldDocument142 pagesYoel Rosenfeldmahlik marshallNo ratings yet

- Jewish Standard, December 8, 2017Document72 pagesJewish Standard, December 8, 2017New Jersey Jewish StandardNo ratings yet

- Yair Harel (Visiting Israeli Artist 2014) - BiographyDocument1 pageYair Harel (Visiting Israeli Artist 2014) - BiographymagnesmuseumNo ratings yet

- Holocaust NotesDocument33 pagesHolocaust Notesapi-288401561No ratings yet

- Kristine Keren Holocaust SurvivorDocument2 pagesKristine Keren Holocaust SurvivorJessi FreezeNo ratings yet

- Descendants of The Anusim (Crypto - Jews) in Contemporary Mexico 2009Document239 pagesDescendants of The Anusim (Crypto - Jews) in Contemporary Mexico 200998fg09nm56sd100% (2)

- Reveiw of Old Testament Theology by MoberlyDocument4 pagesReveiw of Old Testament Theology by Moberly321876No ratings yet

- What Is JudaismDocument50 pagesWhat Is JudaismCharlie P Calibuso Jr.No ratings yet

- Yisro Q&ADocument2 pagesYisro Q&ARabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- The Decline of Jewish Ritual Purity Obse PDFDocument1 pageThe Decline of Jewish Ritual Purity Obse PDFGudino WolfangNo ratings yet

- EJM 054 Decter, Prats - The Hebrew Bible in Fifteenth-Century Spain - Exegesis, Literatura, Philosphy, and The Arts PDFDocument300 pagesEJM 054 Decter, Prats - The Hebrew Bible in Fifteenth-Century Spain - Exegesis, Literatura, Philosphy, and The Arts PDFRes Iudeorum StudiosusNo ratings yet

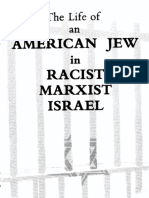

- 1985 - The Life of An American Jew in Racist Marxist Israel - J BernsteinDocument46 pages1985 - The Life of An American Jew in Racist Marxist Israel - J BernsteinSam Sam100% (1)

- Seeking Torah, Seeking God - Psalm 119Document4 pagesSeeking Torah, Seeking God - Psalm 119Lulo GpeNo ratings yet

- Canaanite LanguagesDocument3 pagesCanaanite LanguagesDimitris KakarotNo ratings yet

- The Halachical Status of The Herodian DynastyDocument7 pagesThe Halachical Status of The Herodian DynastyfocusmpublicNo ratings yet

- The Blessings Book: Siddur Tehillat HDocument21 pagesThe Blessings Book: Siddur Tehillat HShmueli GonzalesNo ratings yet

- MethonDocument6 pagesMethonAlthara BaldagoNo ratings yet

- Rav Muschel PDFDocument1 pageRav Muschel PDFMeyer MuschelNo ratings yet