Professional Documents

Culture Documents

978 4 431 67897 7 - 14 PDF

Uploaded by

Sunil Chandra0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesOriginal Title

978-4-431-67897-7_14.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pages978 4 431 67897 7 - 14 PDF

Uploaded by

Sunil ChandraCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

The Brain and Zen

JAMES H. AUSTIN

Summary. This chapter briefly touches on some plausible psychophysiological

considerations involved in several large topics. Topics highlighted include the

attentive aspects of meditation; meditative retreats and the momentary "quickenings"

that can occur during them; the superficial states of absorption; the deeper states

of awakening (kensho-satori) and of "Pure Being"; and the rare later advanced

stage of ongoing enlightened traits. If we wish to understand how the Zen training

process arrives at its transforming potentials, we need to clarify which brain func-

tions are "let go of" during these various steps. The psychophysiology of triggering

mechanisms and the dissociations during transitional intervals are useful points at

which to begin.

Keywords. Zen mechanisms, Enlightenment, Thalamus, Limbic system, Neuro-

messengers

With all your science can you tell how it is,

and whence it is that light comes into the soul?

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

An outline of the Path of Zen is presented in my companion chapter in this volume.

However, no such diagram suffices to answer Thoreau's question, nor could any of the

speculations briefly advanced in these next few pages. For our challenge is (1) to

"explain" meditation and quickenings; (2) next, to clarify the mechanisms underlying

such diverse states as the absorptions, the awakenings (kensho-satori), and Being; and

(3) finally, to explain how a sage's brain could mature into the rare stage of ongoing

enlightened traits. Elsewhere, the following abbreviated comments receive a more

detailed treatment (Austin 1998).

Zen Meditation as an Attentive Art

Starting from the foundations of calmness and clarity, two styles of meditation

emerge. They tend to be used alternately.

Department of Neurology, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO

80262, USA

94

K. Miyoshi et al. (eds.), Contemporary Neuropsychiatry

© Springer-Verlag Tokyo 2001

The Brain and Zen 95

Receptive meditation deploys an open awareness during "just sitting." Employing

a light touch, it becomes a simple, bare, inclusive noticing of events, distracting or

otherwise. Neither focused nor cultivated by struggle, it still notices when attention

strays, then brings it gently back to the present moment. Concentrative meditation is

a focused attentive process more willfully sustained and one-pointed. Finally, one may

become more or less absorbed in it.

True, the right inferior parietal lobule and the right middle frontal gyrus help us

"attend" to events in both sides of extrapersonal space (Johannsen 1997). Yet, attention

remains an "associative" function. It draws on deep subcortical reservoirs, including

the pulvinar of the thalamus. Moreover, most of our processing occurs subconsciously,

effortlessly, preattentively, in less than 1I20'h of a second (Austin 1998, pp. 271-281).

Meditative Retreats Involve Somnolence, Stress

Responses, Sensory-Motor Deprivation, and

Self-Discipline

Yes, breathing out tends to dampen the firing rates of nerve cells in the amygdala, and

theta waves in the EEG may correlate with the intervals of undistracted calmness and

clarity reached during deeper levels of meditation. However, meditators struggle

during prolonged retreats (Austin 1998, pp. 138-140). They struggle not only to

remain attentive and to stay awake but also to endure major degrees of physical and

psychic suffering (Austin 1998, pp. 355-358). During self-emptying (kenosis), one

learns self-discipline.

Retreats, like "Outward Bound" experiences, are opportunities to find the "inner"

self. Retreats become effective agencies of personal change, to the degree that they (1)

evoke in the brain a calibrated series of physiological instabilities and stress responses;

and (2) develop meditators' capacities to endure anguish and to find how much they

create their own discomforts, resistances, and boredom.

"Quickenings" reflect a variety of corresponding surges in the activities of mes-

senger molecules in the brain. Some of these varied phenomena tend to occur at the

advancing tidal edges of conventional arousals. They arise either as part of circadian

(daily) or of ultradian rhythms (every 90 min or so). Quickenings also seem to enter

during the dynamic transitions between waking/drowsiness and sleep/REM sleep.

Quickenings arise especially when the brain's own stress responses-releasing bio-

genic amines, peptides, acetylcholine, glutamate, and GABA-have gone on to desta-

bilize and disrupt sleep cycles and other biorhythms.

States of Absorption, of "Awakening" (Kensho-Satori),

and of "Pure Being"

These phenomena are extraordinary alternate states of consciousness. To understand

Zen, it is essential to observe what they "let go" of, or subtract. In this regard,

certain GABA, and peptide, inhibitory functions can help us understand how

these three categories of states could express such selective "deletions" from

consciousness.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- p1386b PDFDocument290 pagesp1386b PDFSunil Chandra100% (2)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Wellness Worksheet 010Document2 pagesWellness Worksheet 010Abiud UrbinaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lymphatic SystemDocument22 pagesLymphatic SystemdrynwhylNo ratings yet

- Health Assessment ChecklistDocument14 pagesHealth Assessment ChecklistLindy JaneNo ratings yet

- DLL in Science 10 Third QuarterDocument16 pagesDLL in Science 10 Third QuarterAlfred NeriNo ratings yet

- What Is RH Sensitization During PregnancyDocument14 pagesWhat Is RH Sensitization During PregnancyKeisha Ferreze Ann QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Dr. RECKEWEGDocument73 pagesDr. RECKEWEGtaichi767% (3)

- DR Luh - Role of PMR in NICUDocument50 pagesDR Luh - Role of PMR in NICUad putraNo ratings yet

- A Simplified Understanding of Anterior GuidanceDocument5 pagesA Simplified Understanding of Anterior GuidanceSinta Marito HutapeaNo ratings yet

- Leitenberg Henning 1995 Sexual FantasyDocument28 pagesLeitenberg Henning 1995 Sexual FantasyLoui LogamNo ratings yet

- Manju Arora PDFDocument8 pagesManju Arora PDFSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- Exam PDFDocument1 pageExam PDFSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- Ed567093 PDFDocument6 pagesEd567093 PDFSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- Exploring Ghanaian Death Rituals and Funeral PracticesDocument8 pagesExploring Ghanaian Death Rituals and Funeral PracticesSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- VSLW JKTK CHP CKT+KKJ) (KM+S GQ, Ys Jgs VukjaDocument8 pagesVSLW JKTK CHP CKT+KKJ) (KM+S GQ, Ys Jgs VukjaSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- BHHN 107Document6 pagesBHHN 107Sunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- C - C C D R: Hi Ming Hiao Hapter Eath AteDocument13 pagesC - C C D R: Hi Ming Hiao Hapter Eath AteSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- RimjhimDocument7 pagesRimjhimSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- Chapter04 - Quadratic Equation-Jeemain - Guru PDFDocument54 pagesChapter04 - Quadratic Equation-Jeemain - Guru PDFSunil ChandraNo ratings yet

- Summative q2 Weeks 1-2Document21 pagesSummative q2 Weeks 1-2Joehan DimaanoNo ratings yet

- Auto Logous TransfusionDocument39 pagesAuto Logous TransfusionSuresh KumarNo ratings yet

- Full Lab ReportDocument5 pagesFull Lab ReportchampmorganNo ratings yet

- Fits, Faints and Funny Turns in Children - Mark MackayDocument6 pagesFits, Faints and Funny Turns in Children - Mark MackayOwais Khan100% (1)

- Evolution Epidemiology and Etiology of Temporomandibular Joint DisordersDocument6 pagesEvolution Epidemiology and Etiology of Temporomandibular Joint DisordersCM Panda CedeesNo ratings yet

- PermlDocument11 pagesPermlFayeNo ratings yet

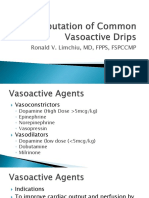

- Computation of Common Vasoactive DripsDocument23 pagesComputation of Common Vasoactive DripsRoxanneGailBigcasGoleroNo ratings yet

- PdaDocument11 pagesPdaMitch C.No ratings yet

- Blood Cell - An Overview of Studies in Hematology PDFDocument360 pagesBlood Cell - An Overview of Studies in Hematology PDFnaresh sharmaNo ratings yet

- Pneumo Tot MergedDocument103 pagesPneumo Tot MergedAndra BauerNo ratings yet

- What Is Life? A Guide To Biology: Second EditionDocument62 pagesWhat Is Life? A Guide To Biology: Second Editionanother dbaNo ratings yet

- Plant and Animal Tissue TestDocument5 pagesPlant and Animal Tissue TestSri Suhartini100% (1)

- Digestive System of Silkworm by R NDocument17 pagesDigestive System of Silkworm by R NRaghvendra NiranjanNo ratings yet

- Formative Assessment Intro To Metabolismm PDFDocument3 pagesFormative Assessment Intro To Metabolismm PDFJoy VergaraNo ratings yet

- Principles of Osteoarthritis - Its Definition, Character, Derivation (Etc.,) - B. Rothschild (Intech, 2012) WWDocument602 pagesPrinciples of Osteoarthritis - Its Definition, Character, Derivation (Etc.,) - B. Rothschild (Intech, 2012) WWSilvia AlexandraNo ratings yet

- SLH S 20 00050Document34 pagesSLH S 20 00050VsnuNo ratings yet

- Structure, Types and Various Methods For Estimation of HaemoglobinDocument49 pagesStructure, Types and Various Methods For Estimation of HaemoglobinChandra ShekharNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Caprine Anatomy: A Complete Text On General and Systemic AnatomyDocument5 pagesEssentials of Caprine Anatomy: A Complete Text On General and Systemic AnatomyBharat KafleNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency AnemiaDocument12 pagesIron Deficiency AnemiaFeraNoviantiNo ratings yet

- Fluid Volume DisturbancesDocument36 pagesFluid Volume Disturbancesafricanviolets9100% (1)

- Patient Care StudyDocument49 pagesPatient Care StudyKwabena AmankwaNo ratings yet