Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2

2

Uploaded by

adiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2

2

Uploaded by

adiCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Review

Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3750

Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Clinical Review for

the General Physician

Muhammad H. Majeed 1 , Sadaf Arooj 2 , Muhammad Abbas Khokhar 3 , Tamoor Mirza 4 , Ali A.

Ali 5 , Zahid H. Bajwa 6

1. Department of Psychiatry, Natchaug Hospital, East Lyme, CT, USA 2. Radiology, Holy Family Hospital,

Rawalpindi, PAK 3. Medical Oncology and Radiotherapy, King Edward Medical University, Lahore , PAK

4. Psychiatry, Clinical Director, Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin, AUS 5. Psychiatry, Icahn School of

Medicine at Mount Sinai, Elmhurst Hospital Center, Flushing, NY, USA 6. Pain Medicine, Tufts University

School of Medicine/Tufts Medical Center, Boston, USA

Corresponding author: Ali A. Ali, aliahsanloona@gmail.com

Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article

Abstract

General practitioners (GPs) are often the first clinicians to encounter patients with trigeminal

neuralgia (TN). Given the gravity of the debilitating pain associated with TN, it is important for

these clinicians to learn how to accurately diagnose and manage this illness. The objective of

this article is to provide an up-to-date literature review regarding the presentation,

classification, diagnosis, and the treatment of TN. This article also focuses on the long-term

management of these patients under the care of GPs. GPs play an important role in the

management of patients with TN by following the evidence-based management guidelines. The

most important aspects of the management of TN are discussed in this review article.

Categories: Family/General Practice, Neurology, Pain Management

Keywords: trigeminal neuralgia, tic douloureux, headaches, pain management, neurology, general

psychiatry, primary care

Introduction And Background

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is also called tic douloureux. The first account of TN is found in the

writing of Avicenna in the 11th century, but it was John Fothergill who gave the modern

description of TN in his 1773 paper on the subject [1]. In the 21st century medicine, the

pathophysiology of TN has been established through a deeper understanding of the physiology

and development of imaging techniques. Due to its episodic nature, its initial presentation and

the long-term management of these patients fall under the care of the general practitioners

Received 09/18/2018

(GPs).

Review began 11/06/2018

Review ended 12/17/2018

Published 12/18/2018 Review

© Copyright 2018 Prevalence

Majeed et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the terms of A survey of the GPs in the United Kingdom reported the incidence of TN as 26 per 100,000 per

the Creative Commons Attribution year, between 1992 to 2002 [2]. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

License CC-BY 3.0., which permits estimates the incidence rate of 12 per 100,000 people per year [3]. There is gender variability in

unrestricted use, distribution, and

the incidence of TN with a female to male ratio of 1.74:1 with most of the cases occurring after

reproduction in any medium, provided

the original author and source are

50 years of age [4].

credited.

How to cite this article

Majeed M H, Arooj S, Khokhar M, et al. (December 18, 2018) Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Clinical Review for

the General Physician . Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750

Presentation

Almost 87% of all facial pains are related to dental or oral mucosal lesions [5]. The most

common causes of facial and jaw pain are listed in Table 1. Clinical history, examination,

investigations, and imaging are important to make a correct diagnosis [6]. TN is characterized

by an abrupt onset and short-lived unilateral shock-like pain, limited to the distribution of the

trigeminal nerve. Triggers for classical TN (CTN) usually include mastication (73%), touch

(69%), tooth brushing (66%), eating (59%), talking (58%), and cold wind on the face (50%).

Combing hair is not usually a common trigger for TN. There can be concomitant background

pain within the distribution of the nerve. Trigger zones are present in more than 90% of the

patients, with touch and vibrations being the most common stimuli in provoking pain. Pain is

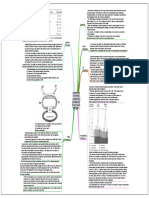

usually distributed along the V2 and V3 branches (Figure 1). Pain occurs slightly more often

(59% to 66%) on the right side of the face and rarely (3% to 5%) is bilateral. Its diagnostic

criteria from The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) are summarized

in Table 2.

Common Causes of Facial Pain

1. Oral cavity and salivary gland lesions (infection, trauma, inflammation, space-occupying lesion)

2. Facial bones and joint diseases

3. Paranasal sinus disease

4. Neuro-vascular disorders

5. Psychosomatic disorders

TABLE 1: Common causes of facial pain

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 2 of 8

FIGURE 1: Overview of distribution of the trigeminal nerve and

its terminal branches

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 3 of 8

ICHD-3 Diagnostic Criteria for Trigeminal Neuralgia

A. Pain has all of the following characteristics:

1. Lasting from a fraction of a second to two minutes

2. Severe intensity

3. Electric shock-like, shooting, stabbing or sharp in quality

B. Precipitated by innocuous stimuli within the affected trigeminal distribution

C. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

TABLE 2: ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for trigeminal neuralgia

ICHD-3: International Classification of Headache Disorders

Clinicians should be aware of other disorders such as painful trigeminal neuropathy that can

present like TN. Herpes Zoster infestation of the trigeminal ganglion of the ophthalmic nerve,

chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, migraine, cluster

headache, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia are among the differential diagnoses of TN. A list of

differential diagnoses is presented in Table 3.

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 4 of 8

Associated

Diagnosis Location Frequency Nature Demographic Treatment

symptoms

Triggered by

Unilateral; ear,

Slightly more swallowing or Pharmacologic

Glossopharyngeal tonsils, Electrical or

Paroxysmal common in coughing; treatment is similar

neuralgia larynx, and lancinating

women spontaneous to TN.

tongue

remissions

High-flow 100%

Unilateral; Episodic;

Stabbing, Ipsilateral; ptosis, oxygen; ergot

ocular, frontal, 15 to 180- 18-40 years

Cluster headache burning, and miosis, tearing, preparations;

and temporal minute Males

throbbing and rhinorrhea prednisone;

areas episodes

methysergide

Multiple Ipsilateral

Chronic Ocular, frontal, Stabbing,

five to 45- conjunctival

paroxysmal and temporal burning, and Females Indomethacin

minute injection,

hemicrania areas throbbing

episodes lacrimation

Unilateral; Conjunctival

15 to 120- Burning,

periorbital, 23 to 77 injection, tearing, Corticosteroids; anti-

SUNHA second stabbing, or

neuralgiform years; males rhinorrhea, and epileptic drugs

episodes electric pain

headache facial flushing

20 years and Ophthalmoplegia;

Tolosa-Hunt Unilateral; retro- Steady gnawing

Constant above; males spontaneous Corticosteroids

syndrome orbital or boring

and females resolution

Unilateral;

Burning pain,

HZ involving the ophthalmic 60 to 70

sometimes Vesicular eruption

trigeminal division in the Constant years; males Antivirals; steroids

accompanied by within seven days

ganglion majority of and females

neuralgic pain

cases

TABLE 3: Differential diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia

HZ: Herpes Zoster, TN: trigeminal neuralgia, SUNHA: short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks

Classification

In the third edition of the ICHD-3, TN is sub-classified into classical, secondary, and idiopathic

causes [7]. In CTN, pain occurs along the distribution of TN without any obvious reasons other

than neurovascular compression. CTN has recurrent paroxysms of unilateral facial pain and

involves pain-free periods or concomitant background facial pain. Persistent background pain,

bilateral symptoms, the patient’s age less than 50 years, focal neurological signs, and sensory

impairment raise the suspicion for etiologies other than CTN. Multiple sclerosis (MS), space-

occupying lesions, and neuropathy are among the common causes of secondary TN (STN). STN

is caused by underlining pathology, and frequently on clinical examination, sensory

abnormalities could be elicited. Patients experience unilateral facial pain in paroxysmal fashion

and may have background continuous or near continuous pain. Multiple sclerotic plaques at the

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 5 of 8

trigeminal root entry zone or in the pons, causing impairment in the TN pathway, are the most

common cause of STN. About 2% of patients with MS have TN [8]. A space-occupying lesion

coming in contact with TN can cause recurrent paroxysms of unilateral facial pain. Idiopathic

TN is a condition that shows the classical symptoms of TN, but neither electrophysiological

tests nor radiological investigations show significant abnormalities. In this review article, we

will primarily discuss CTN.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Several observations lead to the vascular-compression theory of CTN, which indicates that TN

is caused by the pressure of blood vessels on the trigeminal nerve as it exits the brain stem.

Most commonly, a rostroventral superior cerebellar artery loop compresses the trigeminal

nerve and causes the symptoms [9].

Diagnosis

CTN is a clinical diagnosis based on the history of the patient and a thorough physical exam,

particularly a neurological exam. Magnetic resonance imagining/angiography (MRI/MRA) is

often used to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude other possible causes of facial pain. Imaging

techniques can help locate the area of the neurovascular loop as well as find any secondary

causes. Neurophysiological recording of trigeminal brainstem reflexes and trigeminal evoked

potentials help detect the lesion [7]. Medical treatment for most patients with CTN is required.

Medical therapy helps provide relief from excruciating pain and decrease in pain frequency and

duration as well as the associated symptoms. Patients who are resistant to or unable to tolerate

medications can be candidates for surgical treatment.

Treatment

The European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Quality Standards Subcommittee of

the American Academy of Neurology consider carbamazepine (CBZ) as the drug of choice for the

treatment of TN [10]. CBZ is also the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved

medication for the treatment of TN. CBZ is an anticonvulsant that is structurally close to

tricyclic compound imipramine. It works by the inhibition of sodium channel activity and the

modulation of calcium channels. Its efficacy in the treatment of TN is well established. In a

review of several studies, CBZ provided a high level of pain control (58% to 100%), while the

placebo success rate was only 0% to 40% [10]. However, providers should be aware of

tachyphylaxis with the use of CBZ. The typical starting dose is 100 to 200 mg twice daily and

then is gradually increased to 200 mg. The usual maintenance dose is 600 to 1200 mg in divided

doses with a desired therapeutic blood level of 4 to 12 ug/ml. The initial half-life of CBZ is

around 30 hours, but because of auto-induction of cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4, it is

reduced to 10 to 12 hours. This decrease in half-life necessitates monitoring the serum levels,

twice daily dose scheduling, or use of a time-release formulary. The presence of the human

leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B*15:02 allele is a genetic susceptibility marker of developing

Stevens-Johnson syndrome in high-risk (Asians) populations. Patients with Asian ancestry

should be screened for this allele before starting CBZ, and if positive, the use of CBZ should be

avoided. More common side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, and nausea. Severe side

effects include aplastic anemia, hyponatremia, and abnormal liver function tests. Regular

monitoring of blood counts, liver function tests, and serum sodium levels is recommended.

Oxcarbazepine (OXC) is an analog of CBZ that has better tolerability, predictable metabolism,

and fewer interactions with other medications. Both OXC and CBZ were proven equally

effective in the reduction of pain attacks and intensity in at least three head-to-head trials [10].

Serum sodium levels should be periodically monitored in patients taking OXC. Some small,

open-label studies support the use of pregabalin, gabapentin, topiramate, levetiracetam, and

valproic acids as well [11]

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 6 of 8

Local anesthetics such as alcohol, glycerol, phenol, tetracaine, or bupivacaine injections are

used in the diagnosis and treatment of TN [12]. These percutaneous injections can provide

relief from pain for a few months to years. Injections of botulin toxin A also help reduce the

pain intensity and frequency in TN [13]. Patients, whose symptoms are refractory to medical

treatment or if they are unable to tolerate it due to side effects, are preferred candidates for

surgical procedures for the treatment of TN. Usually, surgical therapies involve decompression

of the nerve by resetting the vascular loop around the nerve or sometimes resetting the nerve

that carries the pain signals [14].

Percutaneous trigeminal ganglion balloon compression rhizotomy is usually reserved for

patients who cannot tolerate the above-mentioned treatments or are refractory to it [15].

Percutaneous radiofrequency gangliolysis, trigeminal ganglion compression, and retrogasserian

glycerol rhizolysis are different techniques utilized to ablate the ganglion. These procedures

have high initial success rates. Microvascular decompression (MVD) is conducted under general

anesthesia using a microscope to identify the trigeminal nerves. The artery or vein causing

pressure on the trigeminal nerve is removed or repositioned to relieve the compression. This

procedure is performed endoscopically as well [16]. Stereotactic radiosurgery with Gamma-

knife or Cyber-knife radiosurgery is also used in the treatment of TN [17-18]. Peripheral

neurectomy is reserved for patients who have failed medical and other conservative surgical

treatments or are not suitable candidates for them [19]. The development of atypical facial pain

is a common after-effect of the procedure. TN is usually chronic and may take a psychological

toll on the patient as well. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, a

subdivision of the National Institute of Health, United States, provides information,

treatment, and support to patients suffering from TN and their families [3]. To check for the

efficacy of treatment or its side effects, patients should be monitored at regular intervals with

their general physicians. The recurrence of symptoms is common after medical or surgical

treatment.

Conclusions

TN is a rare disease but often associated with debilitating pain and disability. Various

neurological and infectious causes can mimic its symptoms, and the exact diagnosis is

recommended prior to initiation of treatment. CBZ is the drug of choice and the only FDA

medication approved for TN. Other treatment options include neuroleptic blocks and surgical

alternatives. Given the insidious nature of the disease, general physicians play a crucial role in

the management of TN.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors

declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial

support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships:

All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the

previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or

activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dennis Barbon from Frank H. Netter, MD School of Medicine

for his contribution of Figure 1, Overview of distribution of the trigeminal nerve and its

terminal branches.

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 7 of 8

References

1. Pearce JMS: Trigeminal neuralgia (Fothergill’s disease) in the 17th and 18th centuries . J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003, 74:1688. 10.1136/JNNP.74.12.1688

2. Hall GC, Carroll D, Parry D: Epidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary

care perspective. Pain. 2006, 122:156-162.

3. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Trigeminal neuralgia fact sheet .

(2018). Accessed: April 12, 2018: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-

Education/Fact-Sheets/Trigeminal-Neuralgia-Fact-Sheet.

4. Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralth E, Kurland, LT: Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal

neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Ann Neurol. 1990, 27:89-95.

10.1002/ana.410270114

5. Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al.: The global burden of headache: a documentation of

headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007, 27:193-210. 10.1111/j.1468-

2982.2007.01288.x

6. Quail G: Atypical facial pain--a diagnostic challenge . Aust Fam Physician. 2005, 34:641-645.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The

International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia.

2013, 33:629-808.

8. Hooge JP, Redekop WK: Trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis . Neurology. 1995, 45:1294-

1296. 10.1212/WNL.45.7.1294

9. Love S, Coakham HB: Trigeminal neuralgia pathology and pathogenesis . Brain. 2001,

124:2347-2360.

10. Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, et al.: AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia

management. Eur J Neurol. 2008, 15:1013-1028. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02185.x

11. Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al.: Practice parameter: the diagnostic evaluation and

treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards

Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of

Neurological Societies. Neurology. 2008, 71:1183-1190. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326598.83183.04

12. Goto F, Ishizaki K, Yoshikawa D, Obata H, Arii H, Terada M: The long lasting effects of

peripheral nerve blocks for trigeminal neuralgia using high concentration of tetracaine

dissolved in bupivacaine. Pain. 1999, 79:101-103.

13. Zhang H, Lian Y, Ma Y, Chen Y, He C, Xie N, Wu C: Two doses of botulinum toxin type A for

the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: observation of therapeutic effect from a randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Headache Pain. 2014, 15:65. 10.1186/1129-2377-15-

65

14. Parmar M, Sharma N, Modgill V, Naidu P: Comparative evaluation of surgical procedures for

trigeminal neuralgia. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2013, 12:400-409. 10.1007/s12663-012-0451-x

15. Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Bekar A, Berk C: Percutaneous controlled radiofrequency trigeminal

rhizotomy for the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: 25-year experience with 1,600

patients. Neurosurgery. 2001, 48:524-32.

16. Bohman L, Pierce J, Stephen JH, Sandhu S, Lee JK: Fully endoscopic microvascular

decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: technique review and early outcomes. Neurosurg

Focus. 2014, 37:18. 10.3171/2014.7.FOCUS14318

17. Baschnagel AM, Cartier JL, Dreyer J, et al.: Trigeminal neuralgia pain relief after gamma knife

stereotactic radiosurgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014, 117:107-111.

10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.12.003

18. Karam SD, Tai A, Snider JW, et al.: Refractory trigeminal neuralgia treatment outcomes

following CyberKnife radiosurgery. Radiat Oncol. 2014, 9:257-10.

19. Ali F, Prasant M, Pai D, Aher AV, Kar S, Safiya T: Peripheral neurectomies: a treatment option

for trigeminal neuralgia in rural practice. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012, 3:152-10.

10.4103/0976-3147.98218

2018 Majeed et al. Cureus 10(12): e3750. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3750 8 of 8

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Zhang - Synopsis of The Golden Cabinet With 300 CasesDocument566 pagesZhang - Synopsis of The Golden Cabinet With 300 CasesMarshall100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Case Simulation 123 IjcgDocument3 pagesCase Simulation 123 IjcgIrish Jane GalloNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Infection Prevention BrochureDocument2 pagesInfection Prevention BrochureTeguh Aprian Maulana GultomNo ratings yet

- Abstracts of The 2016 TTS CongressDocument929 pagesAbstracts of The 2016 TTS CongresspksdfpksdNo ratings yet

- Physiology of PregnancysDocument10 pagesPhysiology of PregnancysadiNo ratings yet

- Tan 2013Document12 pagesTan 2013adiNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Pregnancy: Learning ObjectivesDocument3 pagesPhysiology of Pregnancy: Learning ObjectivesadiNo ratings yet

- 6-Physiological Changes of PregnancyDocument12 pages6-Physiological Changes of PregnancyadiNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Normal PregnancyDocument1 pagePhysiology of Normal PregnancyadiNo ratings yet

- A Clinical, Radiological and Etiological Study of Neonatal PneumoniaDocument4 pagesA Clinical, Radiological and Etiological Study of Neonatal PneumoniaadiNo ratings yet

- Uia34 Obstetric and Foetal Physiology - Implications For Clinical Practice in Obstetric Analgesia and AnaesthesiaDocument4 pagesUia34 Obstetric and Foetal Physiology - Implications For Clinical Practice in Obstetric Analgesia and AnaesthesiaadiNo ratings yet

- Alaiyan 2017Document5 pagesAlaiyan 2017adiNo ratings yet

- Alsop 2012Document10 pagesAlsop 2012adiNo ratings yet

- Lazaroni 16Document4 pagesLazaroni 16adiNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Pneumonia in Developing Countries: Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal EdDocument10 pagesNeonatal Pneumonia in Developing Countries: Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal EdadiNo ratings yet

- BCCADocument17 pagesBCCAadiNo ratings yet

- Birkbak 2018Document11 pagesBirkbak 2018adiNo ratings yet

- Body-Stalk Anomaly. A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument5 pagesBody-Stalk Anomaly. A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureadiNo ratings yet

- Sumber DuaDocument6 pagesSumber DuaadiNo ratings yet

- Patogenesis Lesi Pre-Kanker 1Document9 pagesPatogenesis Lesi Pre-Kanker 1adiNo ratings yet

- CBD - Snake Bite Firda WidasariDocument28 pagesCBD - Snake Bite Firda WidasarifirdaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Performance Summary Statistics To Be Posted On The Chaco Website JK Feb27 2017Document1 page2014 Performance Summary Statistics To Be Posted On The Chaco Website JK Feb27 2017api-135630290No ratings yet

- Cardiac Rehabilitation CHF DR Novaria P SPKFRDocument29 pagesCardiac Rehabilitation CHF DR Novaria P SPKFRNovaria PuspitaNo ratings yet

- Quiz 2 Obstetrics Nursing: Untitled SectionDocument11 pagesQuiz 2 Obstetrics Nursing: Untitled SectionBeverly DatuNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 InfoDocument49 pagesCOVID 19 InfoDrop ThatNo ratings yet

- Combined Okell NotesDocument202 pagesCombined Okell Notessameeramw100% (5)

- Biomedicines: EDTA Chelation Therapy in The Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases: An UpdateDocument13 pagesBiomedicines: EDTA Chelation Therapy in The Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Updateniknik73No ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Failure in The ICU COCC 2016Document14 pagesGastrointestinal Failure in The ICU COCC 2016Julia González López100% (1)

- Hypertrophic Lichen Planus - A Case Report: Mirjana PARAVINADocument8 pagesHypertrophic Lichen Planus - A Case Report: Mirjana PARAVINAPruebaNo ratings yet

- 6 Endometrial Polyp - Libre PathologyDocument4 pages6 Endometrial Polyp - Libre PathologyfadoNo ratings yet

- Group-5 - NCP - Ges HypDocument2 pagesGroup-5 - NCP - Ges HypWallen Jey VelascoNo ratings yet

- .Document33 pages.3bdullah al3yuniNo ratings yet

- ACL and HTODocument5 pagesACL and HTOHalawa205No ratings yet

- Positive RT-PCR Test Results in Discharged COVID-1Document12 pagesPositive RT-PCR Test Results in Discharged COVID-1Mustafa MullaNo ratings yet

- ArthritisDocument22 pagesArthritisअनुरूपम स्वामीNo ratings yet

- Pediatric HypoglycemiaDocument2 pagesPediatric HypoglycemiaBelindA1494No ratings yet

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManDocument12 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManChaii De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 6 - Resources - Medical Glossary - SpanishDocument24 pages6 - Resources - Medical Glossary - SpanishLituanya Saldivar100% (1)

- Injection TechniquesDocument11 pagesInjection TechniquesLeon OngNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 Infectious EpidemiologyDocument89 pagesCHAPTER 2 Infectious EpidemiologyteklayNo ratings yet

- MICROBIOLOGY HOMEWORK SET A-QuestionsDocument2 pagesMICROBIOLOGY HOMEWORK SET A-QuestionschristinejoanNo ratings yet

- Criteria Donor of BloodDocument3 pagesCriteria Donor of Bloodapi-269388039No ratings yet

- Taller Ingles 11Document3 pagesTaller Ingles 11SERGIO ReinaNo ratings yet

- Final Literature Review-Antineoplastic AgentsDocument5 pagesFinal Literature Review-Antineoplastic Agentsapi-703108884No ratings yet

- Arbo VirusesDocument67 pagesArbo Virusesneelam badruddin100% (1)

- Pérdida de Músculo Esquelético y Pronóstico de Pacientes Con Cáncer de MamaDocument7 pagesPérdida de Músculo Esquelético y Pronóstico de Pacientes Con Cáncer de MamaJesus Maturana YañezNo ratings yet