Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Did Aristotle Have A Concept of Intuitio

Uploaded by

denisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Did Aristotle Have A Concept of Intuitio

Uploaded by

denisCopyright:

Available Formats

DID ARISTOTLE HAVE A CONCEPT OF “INTUITION”?

Did Aristotle have a concept of “intuition”?

Some thoughts on translating nous

Han Baltussen

In this paper I propose to review existing translations of nous in Aristotle in order

to show that translating it as “intuition” is problematic. A proposal to find a new

direction for interpreting the term is given, based on a richer understanding of the

modern notion of intuition in cognitive psychology. I end with adding some pas-

sages to the usual set which deserve further investigation.

Introduction

In at least three accounts discussing knowledge Aristotle makes certain claims

about how we acquire knowledge, and in one passage he talks about a form of

comprehension which is described as “an unmediated grasp of important founda-

tional concepts” (e.g. APost. 99b20–211). This phrase, translating important Greek

terms, already commits itself to a certain interpretation of key concepts, centered

around nous. In this paper it is my modest aim to discuss an issue connected to

translation and its impact on interpreting concepts. I will first introduce the prob-

lem and its context before dealing with the choices underlying translation. As this

is a preliminary exploration, the net result will be limited and mostly negative in

that I reject the indiscriminate use of “intuition” for nous and only give a rough

sketch of how this line of enquiry could be pursued.2

The usual way to unpack Aristotle’s statement quoted above is to focus on

“unmediated”, and to say that what he means is grasping a state of affairs or an

object without (discursive) reasoning. Reasoning would here have to be deductive

reasoning, so that “unmediated” can also be read as “without explicitly providing

1

I have followed the normal convention of referring to passages in Aristotle, which is to refer to

the page numbers, column letters and/or chapter sections of the standard edition of the works of

Aristotle, edited by Bekker. These page numbers, column letters and chapter sections are repeated

in all modern editions of Aristotle’s works.

2

I take my approach to be complementary to Lesher 1973, who (with some qualifications) also goes

against describing nous as intuition (45, 64), attacking the problem from the Greek side and nar-

rowly focused on APost.

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'?53

Some thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

HAN BALTUSSEN

a cause or a middle term”. The Aristotelian notion I am talking about is of course

nous. The claims Aristotle makes about nous have evoked elaborate discussion, in

particular over the question whether his account of knowledge is really empiri-

cist or whether at the end of his Posterior Analytics in his genetic account of

the acquisition of knowledge (the famous chapter 2.19), he gives in to a form

of rationalism (Kahn, 1981). But in this paper I shall not decide between the

Aristotle, by Francesco Hayez, 1811.

54 thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'? Some

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

DID ARISTOTLE HAVE A CONCEPT OF “INTUITION”?

empiricist or rationalist camp. In most interpretations the notion of nous receives

different translations but many use the term “intuition” — a term which in almost

all cases remains either undefined or under-defined. It is my claim that the trans-

lations cover up the more fundamental issue to what extent the modern concept

of intuition (whatever that is) can be mapped onto Aristotle’s account of nous or

intellect, and whether such categories as “empirical” and “rational” do justice to his

view (cf. Kahn, 1981).

I believe that the translation of nous as “intuition” covers up a misconstrual of

this notion which requires clarification. Moreover, since nous is said to play a role in

the attainment of basic starting-points (APost. 2.1; Topics 1.14), one’s initial reaction

is to resist giving such an important role to what many take to be a non-rational

faculty. It also raises the further question, which I cannot answer here, of how it

relates to the claim that dialectic reaches principles and why Aristotle would need

both. So for now I intend to do two things: first, to look for a clearer and, as I hope

to show, a richer notion of intuition from a contemporary perspective; secondly, to

place this against Aristotle’s implicit and explicit claims about nous. The main part

of the paper constitutes an exploration of the notion “intuition” and is partly in the

form of a critique of some existing interpretations. I stress that it represents a pre-

liminary exploration of a terminological issue which is fundamental to interpreting

Aristotle’s core notion of “unmediated grasp”.

I. Empirical versus a priori?

Given that we do not have one systematic treatise setting out Aristotle’s “theory”

of knowledge, the first problem with his epistemology is that one needs to recon-

struct it from several passages in different works. At least three accounts typical

of his perspectival approach are usually included: there is his account in the On

the soul, dealing with perception and mental processes, another in the Ethics on

mental states preceding proper actions, and yet another one in Posterior Analytics

on a formalised system of demonstration based on unmediated, true premises.

Here it is not obvious how to reconcile the foundationalist claims in his dialectical

methodology with the so-called scientific claims about knowledge. Barnes (1969)

countered the Baconian picture that the Posterior Analytics would be a systema-

tised methodology for scientific investigation, while suggesting that it was rather a

methodology for teaching and imparting knowledge. Yet more recently Burnyeat

(1981) qualified this by pointing out that this would be a poor form of pedagogy,

while he suggests persuasively to view demonstration as a way of imparting under-

standing by leading the advanced student on the basis of her implicit knowledge to

full and understanding by demonstrative method.

Limitations of space do not allow to bring out the investigative role dialectic

(defined in a specific way) can play according to Aristotle and how it is useful in

the search for “first principles” as a kind of meta-theory, so a summary account

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'?55

Some thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

HAN BALTUSSEN

will have to suffice here. Aristotle argues (rightly) that a specific science cannot

determine its own principles within the framework of its own field (Top. 101b;

Rhet. 1352b). Thus dialectic can be construed as a valuable part of scientific metho-

dology, arguing from foundations to the foundations, whereas Posterior Analytics

represents the deductive route arguing from foundations (cf. Evans, 1977).

Let us now consider some of the implicit claims about nous which can be found

in the following translations: “intellectual intuition” (Ross), “mental intuition”

(Alan), “intellect” (Grote), “intuitive reason” (Lee, Ross). These translations seem to

make nous a quasi-mystical element in the account of how we acquire knowledge.

It is important to see that this is not a mere verbal point. The specification of adjec-

tives in e.g. Ross’ and Alan’s version (“intellectual” and “mental”) sound an apolo-

getic note and apparently are meant to qualify the concept in such a way that we

may forgive them for using the word “intuition” at all. Whatever the word means,

they seem to tell us, we should be picking out the intellectual aspect of it, while

implying that there is some other side to intuition, the kind we don’t want here.

While we all use the word “intuition”, and think we more or less know what it

means, this seems to involve some kind of self-referential justification in that we

very often don’t make explicit what it means. To put it another way, we seem to

know intuitively what the word “intuition” means. This is highly uninformative

and smacks of circularity. But in approaching an ancient thinker with similar and

systematic concerns about knowledge it is unwise not to be explicit about such

complex terms. One simply does not want to import unwarranted meanings or

notions. The least one can say, and usually does say, is that intuition involves

immediacy in grasping objects or states of affairs. But that seems hardly sufficient.

So should we say intuition is a composite of intellectual and non-intellectual ele-

ments, or can it only be one of these? Or is there yet another way of interpreting

it? Whichever way we do interpret it, it seems clear that our own (modern) idea

of intuition is likely to be of importance in trying to define Aristotle’s nous. We

should however beware that we do not import or impose our notions onto his,

which as we just saw leads to an awkwardly apologetic or distorted rendering of

terms.

There is currently considerable debate and progress on our understanding

of intuitive knowledge and its role in discovery and creative thinking. I want to

explore how contemporary views on workings of the mind might help understand

this idea of immediacy and insight in Aristotle. I here make selective use of some

current ideas on intuition in cognitive sciences, most of which make no reference

to Aristotle.

A recent account of intuition in the area of psychology will help us establish

some firmer ground for defining intuition on the basis of evidence acquired in

experiments. G. Claxton has written a broad study on the role of intuition collect-

ing up the results of empirical investigations spanning several decades. His aim

is encapsulated in a remark about the still current position towards the notion of

56 thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'? Some

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

DID ARISTOTLE HAVE A CONCEPT OF “INTUITION”?

intuition: “Those who disparage intuition are reacting, often unwittingly, against

the presumption that intuition constitutes a form of knowledge that is ‘higher’ than

mere reason, or even infallible” (Claxton, 1998:50). A two-step analysis will show

how we can make sense of this statement, and it will also allow us to argue about

the relation between the rational and non-rational in a meaningful way. I should

stress that Claxton is not trying to clarify intuition per se or — to mention another

common example in this context — to explain such things as the female intuition

of mothers who just “know” what their babies want (without wanting to disparage

this). Claxton rather focuses on creative thought, in particular when we are forced

to deal with new and complex situations which require creative decisions. The evi-

dence shows that decisions made after study and reflection of complex data usually

arise without full awareness of their origin. His emphasis is also more on the proc-

ess of intuition as non-linguistic thought rather than on its results and the question

to what extent they are a reliable basis for belief or decisions.

I shall start by provisionally adopting Claxton’s new definition for intuition:

“a mental process which is non-conscious, but nevertheless rational”. This work-

ing definition will allow us to disentangle the rational from the irrational within

the concept of intuition, which Claxton sees as a kind of borderline phenomenon

between conscious and non-conscious thought. Claxton’s analysis is based on a

very interesting synthesis of a range of recent experiments into creative non-con-

scious mental processes which exhibit patterns indicating a degree of rule-follow-

ing and consistency (i.e. they can be termed rational). Experts have agreed for some

time that the Freudian notion is untenable, that is, we should not divide the mind

up into conscious and subconscious, in which the second is that infamous quag-

mire of problems from one’s personal past. It remains to be seen, however, to what

extent the negative aspect of the Freudian dichotomy still influences the way in

which we speak about intuition and a concept such as Aristotle’s nous. The sense of

embarrassment noticeable in the authors of the early twentieth century, indicates

that they were not yet free from this implicit set of values regarding the oppositions

rational/conscious and non-rational/unconscious.

As an alternative to the Freudian picture of intuitive thought Claxton argues

persuasively for a double threshold in our mental make-up, one between the con-

scious and non-conscious, while further subdividing the non-conscious into two

sections, one of which is located “below” the conscious and above the subconscious.

The criterion here is accessibility, that is, the extent to which we are consciously

aware of our mental operations. On the basis of indirect evidence, certain non-

conscious processes can be shown to be rational, in the sense that they obey

certain implicit rules (for example, we normally anticipate the shape and size of

a room upon entering, assuming it will not have a floor slanting at a very sharp

angle; experiments using optical illusions show that the suggestion of a sharp slant

upon entering a room will take us by surprise and influence our body movements

accordingly without conscious decisions). One major outcome of the experiments

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'?57

Some thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

HAN BALTUSSEN

is that there is a very active (though slow) mode of thinking, which, while non-con-

scious, has a major role in creative thought. Such evidence is mostly indirect, but

the sample is considerable and accumulative. The basic mechanisms of this “under-

mind” (Claxton, 1997:52) are analogy and imagery, and it is non-linguistic thought

which operates according to certain rules. That is the reason why I think this can be

helpful in looking at Aristotle’s notion of “unmediated insight” or “comprehension”

(Barnes): just because we don’t know where an idea is coming from does not mean

it cannot be valuable.

The implications of this division of the mind are considerable. First, it helps

to demystify those activities of the mind which are involved in creative thinking,

famously reported by scientists as thinking in images when reaching important

insights or making breakthrough discoveries (Kekule, Einstein). Second, it allows

for a form of rational thought at a non-conscious level which can be used as an

explanatory factor in making thinking responsible for the premature articulation of

ideas. The transition from this implicit knowledge to a more explicit form might be

exemplified, for example, by the so-called “tip-of-the-tong phenomenon”, where cer-

tain ideas only “break” through the (upper) threshold into our consciousness when

one is relaxed and uninhibited by rational control. Claxton’s aim is to make us trust

our intuitions more, ours is to reach a more detailed understanding of intuition.

II. Aristotle and premature articulation

If we now go back to Aristotle, this picture can be usefully tested. There are obvious

similarities with this notion of “intuitive” thought as the premature articulation of

ideas and intuition.3 It would of course be rash to think there can be a full overlap

in the features that are emerging from modern cognitive views and the functions

ascribed to nous, as there are also some clear differences. For instance, the contem-

porary view is not that intuition is infallible (see Claxton quote p. 4; cf. Kal, 1988:47

ff.) whereas for Aristotle nous itself cannot err (APost. 2.19, 100b7–8). But what this

more explicit and richer notion of intuition does do is avoid the embarrassment

of the irrational so often implied in the corrective definitions and translations dis-

cussed earlier: by allowing for a non-conscious, or pre-conscious, stage of thinking

which exhibits regularity (“rules”), we can be justified in thinking that non-con-

scious thought is not fully irrational.

What kind of work did Aristotle expect the nous to do? We can glean certain

things from the way in which he positions it at the centre of the theoretical and

practical, featuring in both intellectually high-order insight and as immediate grasp

as a basis for know-how (practical nous in the ethics and crafts, EN 6). Aristotle

makes at least the following claims (based on Lesher and Barnes):

3

Cf. Kahn, 1982, 396: “the preliminary or pre-scientific recognition of a phenomenon”.

58 thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'? Some

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

DID ARISTOTLE HAVE A CONCEPT OF “INTUITION”?

(1) it is “more accurate” (akribesteron) than any other kind of knowledge

(100b8–9) and “more true” than episteme (not be taken as infallibility, as Lesher

points out [63], since both episteme and nous are always true. Akribeia here

seems to mean “most in possession of its first principles”)

(2) it is also called both gnôsis (“knowledge by acquaintance”) and epistêmê

(“scientific knowledge”), 99b24, cf. 71b16, 72b18–21, 76a 16–22 (Burnyeat 1981:

131)

(3) it is a way of grasping things which are most knowable and familiar in them-

selves (100b9–10; cf. 72 b24–5), a disposition (hexis gnôrizousa) which implies

full conviction and understanding (presumably “full” as opposed to “implicit”

or “partial”)

(4) nous represents a more abstract level of understanding, in the sense that it

is said to be “further from perception” (inferred from 86a29, cf. Barnes, 1993:

187).

These features suggest a path to understanding which allows empirical input

(Lesher, 1973:62): obviously much more is involved, but it is clear that Aristotle

allows it to be reached by induction. So if we adhere to the sense of “intuition”

defined as a grasp of things in an unmediated way, we can, I think, still use the

term for nous. Think of a person concerned with making moral decisions and how

to explain her reasoning in such a way that she would not have to go through a

syllogism first before implementing action, yet somehow she knows the reason for

doing it (a worry about Aristotle’s picture). This form of intuitive grasping might

account for that, since the suppressed premise is grasped (as in the enthymeme).

One consequence of this position seems to be that we have to reject Lesher’s

rejection of “intuition”. He tentatively presents two definitions, one (which he

accepts) is rather bland and uninformative: “simply to have an insight or realize a

truth” (1973:64). The other is “a faculty which acquires knowledge about the world

in an a priori or non-empirical manner” (ibid.). I think the underlying distinction

between intuition and empirical is a telling one. It limits intuition to the part of

mental activity which is not relying on empirical evidence.

His conclusion that nous is “the grasp of the universal principle, acquired by

induction from particular cases and constituting the source of scientific knowl-

edge” seems plausible. This interpretation allows us to determine to what degree the

grasp of principles involves reasoning of some or any kind. I would also hold that

it saves us from the suppressed embarrassment of requiring a term which needs

“upgrading” to become philosophically acceptable. Barnes’ term “comprehension”

avoids that aspect by sufficiently indicating intellectual activity, but it seems an

impoverishment in relation to the perceptual basis of intuitive thought.

I admit that this thumbnail account is only a first exploration and leaves much

undiscussed, such as the role of phantasia which is an important factor in memory,

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'?59

Some thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

HAN BALTUSSEN

dreaming and as intermediary between perception and thought. Another impor-

tant question is whether we can attribute to Aristotle a notion of unconscious proc-

esses at all. It is this particular question which I want to look at briefly as a way of

indicating the next possible step in the analysis of nous.

III. Unexplored territory: pre-conscious

processes in Aristotle?

If I am right to take this revised version of nous as sometimes representing sud-

den unmediated grasp, this could lead to an interesting follow-up. It allows for

certain aspects of Aristotle’s remarks to be taken as an indication of an awareness

of unconscious processes. Granted, it is of course one thing to use contemporary

concerns and research into intuition as a way of clarifying Aristotle’s — in itself a

justifiable method in history of philosophy —, it is quite another to claim that he

came close to a notion of intuition like ours. I shall therefore present a few exam-

ples to see whether there is room for further narrowing the gap between his notion

and ours. This means I will tentatively explore some passages rather than present a

fully argued case.

Four passages come to mind which exhibit features hinting at creative thought:

(i) analogical thought is mentioned in Topics 1.15–18, where he discusses the

instruments for coming up with arguments and propositions, and recommends

trying to think “laterally”, across generic borders of certain areas and disciplines;

(ii) pictorial thought processes are mentioned in On Memory which somehow

gives place to the non-linguistic (perhaps to be compared to some aspect of

phantasia).

In addition, there are those thought processes we are not always aware of while

they occur:

(iii) In On Dreams he speaks of “unnoticed” stimuli which do occur and return

in dreams. What could these be, and what does he mean by “unnoticed” (after

all he is able to talk about them)?

(iv) Finally, he mentions a mental activity called ankhinoia: “a talent for ‘quick

thinking’”, which in the context of syllogistic reasoning means “‘spotting’ the

middle term (cause) in an imperceptible time” (APost. 1.34, 89b10–11; Barnes

translates “acumen”). Here the language resorts to visual metaphors, as if it were

only a matter of “seeing” the solution: what Aristotle may be trying to convey

here is the immediate and non-linguistic aspect of thought. It is “immediate”

both in time and in appearance, because it takes no time at all, and lacks “media-

tion” by way of intermediate premises or steps.

60 thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'? Some

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

DID ARISTOTLE HAVE A CONCEPT OF “INTUITION”?

These examples may exhibit rather superficial similarities with what we now think

of as intuitive thought. Yet the views expressed exhibit, if not explicitly then per-

haps intuitively, a grasp of certain aspects of non-conscious processes in our men-

tal make-up. This deserves a closer look, not only to arrive at better documented

picture of his account of mental states, but also to explore further whether his

view on an understanding of, and thinking about, the world was setting out on a

new path by including less obvious features of our mental capacities into a wider

epistemological framework.

To conclude, I hope to have shown that a way of approaching the issue of

“unmediated grasp of basic concepts” from a new angle can be fruitful. The con-

ceptual analysis will need to progress by reformulating the problem as to how we

can think about nous and its contemporary counterparts. Post-Freudian analysis

requires awareness of the cultural baggage involved in common parlance about the

mind’s characteristics and activities. The lack of a full overlap between Aristotelian

nous and our modern “intuition” warns us not to clarify one problematic term with

another.

Bibliography

Barnes, 1969

J. Barnes, “Aristotle’s Theory of Demonstration”, Phronesis 14:123–152.

Barnes, 1984

J. Barnes, The Complete Works of Aristotle (Princeton, 2 vols).

Barnes, 1993

J. Barnes, Aristotle. Posterior Analytics (Oxford University Press 1993; first ed. 1975).

Bolton, 1987

R. Bolton, “Definition and Scientific Method in Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics and Genera-

tion of Animals”. In Philosophical Issues in Aristotle’s Biology, ed. A. Gotthelf and J. G. Len-

nox, (CUP, Cambridge–New York), 120–66.

Burnyeat, 1981

M. Burnyeat, “Aristotle on Understanding Knowledge.” In Aristotle on Science: The Posterior

Analytics, ed. E. Berti: 97–139.

Claxton, 1998

G. Claxton, Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind. How Intelligence Increases When You Think Less

(Fourth Estate, London; first ed. 1997).

De Paul – Ramsey, 1998

M. De Paul, M. and W. Ramsey, Rethinking Intuition. The Psychology of Intuition and its role

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'?61

Some thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

HAN BALTUSSEN

in philosophical Inquiry. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Evans, 1977

J. D. G. Evans, Aristotle’s Concept of Dialectic (Cambridge).

Kahn, 1981

C. Kahn, “The Role of Nous in the Cognition of First Principles in Posterior Analytics II,

19”. In Aristotle on Science: The Posterior Analytics, ed. E. Berti: 385–414.

Kal, 1988

V. Kal, On intuition and discursive reasoning in Aristotle (Leiden–New York, 1988).

Lesher, 1973

J. Lesher, “The Meaning of ‘nous’ in the Posterior Analytics”, Phronesis 18:44–68.

Ross, 1949

W. D. Ross, Aristotle’s Prior and Posterior Analytics (Oxford).

Tredennick, 1960

H. Tredennick, Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics (Greek and English transl., Loeb Harvard

University Press 1960).

62 thoughts on translating 'nous'. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and

Baltussen, Han. 2007. Did Aristotle have a concept of 'intuition'? Some

G. Couvalis (eds.) "Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial International Conference of Greek Studies,

Flinders University June 2005", Flinders University Department of Languages - Modern Greek: Adelaide, 53-62.

Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au

You might also like

- IGO2016Document29 pagesIGO2016denisNo ratings yet

- 2nd Iranian Geometry Olympiad: September 2015Document13 pages2nd Iranian Geometry Olympiad: September 2015denisNo ratings yet

- IGO2017Document25 pagesIGO2017denisNo ratings yet

- 6 Iranian Geometry Olympiad: Contest Problems With SolutionsDocument43 pages6 Iranian Geometry Olympiad: Contest Problems With SolutionsdenisNo ratings yet

- Fifth Iranian Geometry Olympiad: The Problems Along With Their SolutionsDocument30 pagesFifth Iranian Geometry Olympiad: The Problems Along With Their SolutionsdenisNo ratings yet

- Online Books by Topic: Online Resources For Olympiad TrainingDocument1 pageOnline Books by Topic: Online Resources For Olympiad TrainingdenisNo ratings yet

- past tense (минало време) past participle (минало причастие)Document14 pagespast tense (минало време) past participle (минало причастие)denisNo ratings yet

- IGO2015 Solutions English PDFDocument33 pagesIGO2015 Solutions English PDFNarendrn KanaesonNo ratings yet

- Sting: Shape of My HeartDocument3 pagesSting: Shape of My HeartdenisNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Forensic Analysis of GlassDocument9 pagesForensic Analysis of GlassAbrea AbellaNo ratings yet

- REELY Chapter 7 Flashcards - QuizletDocument2 pagesREELY Chapter 7 Flashcards - QuizletCERTIFIED TROLLNo ratings yet

- Executive MBA BrochureDocument36 pagesExecutive MBA BrochureAzad AMİROVNo ratings yet

- MT Evenness Tester 2341 EN 2022-03Document4 pagesMT Evenness Tester 2341 EN 2022-03Quynh TrangNo ratings yet

- Econ 620 SyllabusDocument3 pagesEcon 620 SyllabusTOM ZACHARIASNo ratings yet

- Man and Historical Action PDFDocument19 pagesMan and Historical Action PDFAldrin GarciaNo ratings yet

- Akash Final PDFDocument28 pagesAkash Final PDFMohnish AkhilNo ratings yet

- Rijwana Hussein Final EssayDocument18 pagesRijwana Hussein Final EssayhusseinrijwanaNo ratings yet

- 2019jahh 22 447GDocument12 pages2019jahh 22 447GTomi DwiNo ratings yet

- Thetentrin: DeviceDocument84 pagesThetentrin: Deviceorli20041No ratings yet

- 1.3. Intention of This StudyDocument1 page1.3. Intention of This StudyJack FrostNo ratings yet

- A Level Physics Units & SymbolDocument3 pagesA Level Physics Units & SymbolXian Cong KoayNo ratings yet

- Project Plan FLIP FLOPDocument5 pagesProject Plan FLIP FLOPClark Linogao FelisildaNo ratings yet

- Application of Spatial Technology in Mal PDFDocument8 pagesApplication of Spatial Technology in Mal PDFdevNo ratings yet

- 2020 Oulade The Neural Basis of Language DevelopmentDocument7 pages2020 Oulade The Neural Basis of Language DevelopmentzonilocaNo ratings yet

- Layers - of - The - Atmosphere Final Na GrabeDocument23 pagesLayers - of - The - Atmosphere Final Na GrabeJustine PamaNo ratings yet

- Factoring Perfect Square Trinomials: Lesson 4Document29 pagesFactoring Perfect Square Trinomials: Lesson 4Jessa A.No ratings yet

- Activity 9 Measuring Mass Calculating DensityDocument5 pagesActivity 9 Measuring Mass Calculating Densityapi-285524270No ratings yet

- PHINS Guideline - Rev A3Document63 pagesPHINS Guideline - Rev A3Marzuki ChemenorNo ratings yet

- Motivation TheoriesDocument26 pagesMotivation TheoriesShalin Subba LimbuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Issues On Human DevelopmentDocument25 pagesChapter 3 Issues On Human DevelopmentJheny Palamara75% (4)

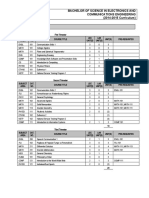

- Program Structure: Bachelor of Science in Electronics and Communications Engineering (2014-2015 Curriculum)Document5 pagesProgram Structure: Bachelor of Science in Electronics and Communications Engineering (2014-2015 Curriculum)Zainab KadhemNo ratings yet

- SQL Statement Select From Per - People - F Where Person - Id 130Document37 pagesSQL Statement Select From Per - People - F Where Person - Id 130pankajNo ratings yet

- Appendix A 2Document7 pagesAppendix A 2MUNKIN QUINTERONo ratings yet

- MSDS - SpaDocument6 pagesMSDS - SpaChing ching FongNo ratings yet

- SAQOL 39 Proxy Version Sr55z7Document5 pagesSAQOL 39 Proxy Version Sr55z7Fernanda VegaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelWarda Ul HasanNo ratings yet

- Applications: Functions andDocument350 pagesApplications: Functions andJason UchennnaNo ratings yet

- IAL Mathematics Formula BookDocument34 pagesIAL Mathematics Formula BookHaleef Mk0% (1)

- ManualDocument272 pagesManualAkash AroraNo ratings yet