Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Intra-Operative Peritoneal Lavage - Who Does It An PDF

Uploaded by

Ad NanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Intra-Operative Peritoneal Lavage - Who Does It An PDF

Uploaded by

Ad NanCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/7691517

Intra-operative peritoneal lavage - Who does it and why?

Article in Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England · August 2005

DOI: 10.1308/1478708051847 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

59 3,253

5 authors, including:

Matthew G Tytherleigh Steven Thrush

Burjeel Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE National Health Service

29 PUBLICATIONS 590 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 313 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Ridzuan Farouk

National University Hospital - NUH

106 PUBLICATIONS 3,838 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Coloproctology techniques View project

The iBRA (implant Breast Reconstruction evAluation) Study View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Matthew G Tytherleigh on 27 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

AUDIT

The Royal College of Surgeons of England

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 255–8

doi 10.1308/1478708051847

Intra-operative peritoneal lavage – who does it and

why?

OJH WHITESIDE1, MG TYTHERLEIGH1, S THRUSH2, R FAROUK1, RB GALLAND1

1

Department of Surgery, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK

2

Department of Surgery, Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford, UK

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION Intra-operative peritoneal lavage (IOPL) is widely practised but its benefits are unclear. The frequency and pat-

tern of its use amongst general surgeons is investigated.

METHODS A postal questionnaire was sent to 153 general surgical consultants and registrars enquiring about their use of

IOPL. The surgeon was asked the volume and type of lavage fluid used, under various circumstances.

RESULTS 118 (77%) questionnaires were returned. 115 (97%) surgeons used IOPL. The majority of surgeons (61%) lavaged

until the fluid was clear, 20% used more than 1 l and 17% used between 500–1000 ml. In the case of the dirty abdomen

(i.e. gross pus or faecal peritonitis), 47% used saline as the lavage fluid, 38% aqueous betadine, 9% water and 3% antibiotic

lavage. Similar results were found in the case of a contaminated abdomen (i.e. a breached hollow viscus). 34% of surgeons

used IOPL during clean cases. 36% used water lavage during intra-abdominal cancer surgery; 21% lavaged with saline and

17% with betadine. More registrars (47%) than consultants (29%) lavaged with water during cancer surgery. Consultants, how-

ever, used more aqueous betadine.

CONCLUSIONS The frequency of use and choice of lavage fluid varies widely. The successful management of the septic

abdomen rests on at least 3 tenants – systemic antibiotics, control of the source of infection and aspiration of gross contami-

nants. There is little good evidence in the literature to support IOPL in the management of the septic abdomen. The use of

IOPL during cancer surgery is supported by in vitro evidence. The current use of IOPL, as shown by this study, appears not to

be evidence based.

KEYWORDS

Intra-operative peritoneal lavage

CORRESPONDENCE TO

Mr RB Galland, Department of Surgery, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading RG1 5AN, UK

E: Robert.Galland@rbbh-tr.nhs.uk

The initial management of peritoneal sepsis is clearly woman by Morse in Norwich in 1911 and he employed 17

established and includes general resuscitation, aspiration of pints of hot water to lavage the abdominal cavity.4 At this

gross contaminants, instigating systemic treatment with time in the US, however, Deaver began to question the use-

antibiotics and ultimately controlling the source of contam- fulness of IOPL, declaring that it was important not to

ination.1 Though these measures are beyond dispute, intra- spread infection across the peritoneal cavity through the

operative peritoneal lavage (IOPL) is also undertaken regu- use of lavage.5 This philosophy was also adopted in the UK

larly with the aim of reducing peritoneal contamination. as evidenced by Lord Moynihan in 1926, and IOPL was all

This treatment is controversial and may owe more to histor- but abandoned.6 A resurgence of IOPL occurred in the late

ical use than any real scientific evaluation. 1950s as a result of Burnett who wrote a seminal paper on

IOPL appears to have been first performed in 1905 by a the treatment of peritonitis using peritoneal lavage.3 This

gynaecologist, Joseph Price, who advocated lavage with showed that patients with a contaminated peritoneum had

sterile water.2 A few years later, in 1911, a surgeon named an improved outcome having undergone lavage. Since then,

Torek, found that saline lavage reduced the mortality of numerous papers have examined the use of various irriga-

patients from 100% to 33%.3 The first successful closure of tion fluids but debate continues as to whether lavage should

a perforated gastric ulcer was performed on a 20-year-old be undertaken and, if so, which solution should be used.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 255–8 255

WHITESIDE TYTHERLEIGH THRUSH FAROUK GALLAND INTRA-OPERATIVE PERITONEAL LAVAGE – WHO DOES IT AND WHY?

IOPL may have four functions. All fluids, including ster- or faecal peritonitis), 47% used saline as the lavage fluid,

ile saline and water, may act as a physical cleaner, washing 38% aqueous betadine, 9% water and 3% antibiotic lavage

away bacteria debris and body fluids such as blood or bile. (Fig. 1). Similar results were found in the case of a contam-

Lavage with such fluids will also have a dilutional effect inated abdomen (presence of a breached hollow viscus).

when instilled and then aspirated from the abdomen. Of surgeons, 34% used IOPL during clean cases. In addi-

Another function is that of an antibacterial agent. tion, 36% used water lavage during intra-abdominal cancer

Antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine and povidone iodine or surgery; 21% lavaged with saline and 17% with betadine.

antibiotics, such as tetracycline, cephradine and metronida- More registrars (47%) than consultants (29%; P < 0.05)

zole, may be toxic to bacteria. Finally, IOPL may result in lavaged with water during cancer surgery. Consultants used

tumour and bacterial cell lysis, an effect that is dependent more aqueous betadine. Two consultants noted that they

upon cell tonicity. would have used tetracycline lavage but were prevented

We have undertaken to look at the current practice with- from doing so by the hospital pharmacy. There were no

in two regions and relate this to the literature. regional differences in the use of IOPL.

Methods Discussion

A simple questionnaire was sent to general surgical con- IOPL is a procedure employed frequently, yet there is little

sultants and registrars working in the Oxford and South West evidence to show its benefits. This survey of a group of

Thames regions. The questionnaire asked about the volume, general surgeons shows the diverse opinions and practices.

type and under what circumstances IOPL would be used. The vast majority of surgeons used IOPL, the main premise

for this being the dilution and removal of contamination

from within the abdomen. At first, this seems logical but

Results

does have one main disadvantage; the conversion of a

A total of 153 general surgeons working in the Oxford and localised area of contamination to a generalised one has

South West Thames regions at the time of the study were been shown to occur experimentally using radiolabelled

sent questionnaires. Of these, 118 (77%) responded and 115 markers.7 There are two clinical studies that are relevant.

(97%) surgeons used IOPL. The first was an uncontrolled, non-randomised study of 21

The majority of surgeons (61%) lavaged until the fluid patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery who had

was clear, 20% used more than 1 l and 17% used 500–1000 IOPL with 5 l of normal saline and received no peri-

ml. In the case of the dirty abdomen (presence of gross pus operative intravenous antibiotics.8 This showed that,

despite a large decrease in bacterial counts shown on swabs

taken from all areas of the abdomen, the lavage group had

high rates of postoperative wound infection (47%), intra-

abdominal abscess (26%) and septicaemia (13%) when

compared to the control group (rates of 37%, 8% and 3%,

respectively). The authors attribute this to the dis-

semination of organisms by the fluid. Lack of use of

intravenous antibiotics is also likely to have played a role.

The practice of IOPL following a standard appendicectomy

is now discouraged as it spreads contamination around the

peritoneal cavity.

The second was a prospective randomised trial using

Ringer’s lactate as the IOPL fluid and compared this with

simple removal of contamination with suction. This

revealed no difference in mortality and septic complication

rates. Peri-operative intravenous antibiotics were used.9

The history of lavage with antiseptics can be traced back

to 1923 when alcohol was used to reduce mortality in peri-

tonitis from 100% to 4%.10 Since then, the lack of toxicity of

saline to micro-organisms gave added interest to antiseptics.

However, although they have a wide spectrum of activity and

Figure 1 The use of different types of lavage fluid. a rapid action, there is a problem with toxicity to the native

tissues. Platt et al.10 performed an animal study comparing

256 Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 255–8

WHITESIDE TYTHERLEIGH THRUSH FAROUK GALLAND INTRA-OPERATIVE PERITONEAL LAVAGE – WHO DOES IT AND WHY?

povidone iodine, taurolin, noxythidin and chlorhexidine as In 1986, Silverman et al.20 ran a prospective randomised

intraperitoneal antiseptics, though without actually study of 159 patients who had undergone either elective or

lavaging, and found chlorhexidine significantly reduced emergency intestinal surgery. The authors compared nor-

early mortality though this was not maintained beyond 5 mal saline lavage with lavage using 2 l of normal saline

days postoperatively. Povidone iodine has undergone two containing 2 g of tetracycline. Again, there was a reduction

prospective randomised studies. The first in 1979 evaluated in wound infection but no difference in intra-abdominal

IOPL with 1% povidone iodine and showed an incidence of abscess formation or septicaemia. All patients received

1.3% intra-abdominal abscess compared to 10.2% in those intravenous antibiotics including metronidazole and one

who had saline lavage.11 All patients had peri-operative other antibiotic.

intravenous antibiotics. Weaknesses in this study include Schein et al.21 performed a prospective randomised trial

the lack of mortality data and the possibility of increased of 87 patients undergoing emergency laparotomies for peri-

intra-abdominal abscess in those who survived a more tonitis. Patients were randomised to receive no IOPL, IOPL

severe peritonitis. Vallance and Waldron12 found no differ- with saline or IOPL with chloramphenicol solution. The

ence between povidone iodine and saline IOPL in these cir- authors concluded that neither IOPL with saline or antibi-

cumstances. Again, this paper has a small number of otics influenced the outcome for these patients in terms of

patients (53) and had an uneven randomisation allocation mortality or wound infection rates.21

with more patients with appendicitis in the saline group and Wound infection could be reduced by IOPL but this may

relatively more bowel perforations in the povidone iodine also be achieved with instillation of topical antibiotics into

group. Interestingly, they also found that chlorhexidine the wound. There is no good evidence to show that IOPL

lavage made no difference. The use of taurolidine has also with antibiotics is any better than conventional peri-opera-

been investigated but only by a retrospective, non-controlled tive intravenous antibiotics.

study which showed a reduction in mortality and morbidity Continuous peritoneal lavage is a recognised treatment

when used during appendicectomy.13 This was not confirmed, for acute pancreatitis, though controversial. A meta-analy-

however, during a randomised trial.14 Hydrogen peroxide sis evaluating continuous peritoneal lavage in acute pan-

lavage was investigated by Lawson and Lavery15 using an ani- creatitis over eight randomised prospective clinical trials

mal model and demonstrated that normal saline lavage was including a total of 333 patients did not reveal a significant

superior to no lavage or lavage with hydrogen peroxide solu- improvement in the mortality or morbidity with the use of

tion which appeared to have greater toxicity than benefit. this technique.22

There is no controlled in vivo data available. The role of IOPL and cancer surgery has a number of

The discovery of penicillin, in 1928, and then the devel- important considerations, which have been investigated in

opment of further antibiotics led to the inevitable use of the case of colorectal cancer. Umpleby et al.23 showed that

antibiotics as lavage fluids. The first use is attributable to viable exfoliated cancer cells were frequently present in

Dees16 and subsequently nearly every available antibiotic large numbers at the site of intestinal anastomoses, sup-

has been used. Important considerations include the reach- porting their potential role for suture-line recurrence. Yu

ing of therapeutic serum levels from peritoneal installation and Cohn24 showed that tumour spillage at the time of the

in order that bactericidal effects can be obtained within 1 operation is a major cause of cancer recurrence. Cancer

min following exposure of bacteria to topical antibiotics.17 cells have also been found on the doughnuts of bowel fol-

Krukowski et al.18 advocated the use of tetracycline solution lowing the use of the circular stapler.25 Rectal washout with

as a lavage fluid, reporting excellent results. saline has been shown to reduce the number of cancer cells

Many earlier studies into IOPL did not routinely employ within the lumen and at the site of the anastomosis.26,27 The

intravenous antibiotics and were not randomised or con- best results, however, come from performing the rectal

trolled; therefore, it is difficult to relate them to this day and washout with a hypotonic solution such as water and/or

age. In 1967, Noon et al.19 took 430 patients with peritoneal antiseptic.28,29 To take this evidence further, if the presence

contamination, performing saline lavage on half and com- of exfoliated cancer cells lying within the peritoneum were

paring them with a study group in which kanamycin and a cause of local recurrence, then theoretically, IOPL would

bacitracin were used for lavage and irrigation of the subcu- be useful to reduce the number of cancer cells and, hence,

taneous tissues. The majority of patients had intravenous the future local recurrence rate.

antibiotics in the postoperative period. Septic complica-

tions, the majority of which were wound infections, were

Conclusions

found to be twice as common in the control group, but the

mortality and the incidence of intra-abdominal abscess The successful management of the septic abdomen rests on

were the same in both groups. This suggests that wound at least three tenants – use of systemic peri-operative

infection is reduced with the use of topical antibiotics. antibiotics, control of the source of infection and aspiration

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 255–8 257

WHITESIDE TYTHERLEIGH THRUSH FAROUK GALLAND INTRA-OPERATIVE PERITONEAL LAVAGE – WHO DOES IT AND WHY?

of gross contaminants.1 IOPL is routinely undertaken if pus 14. Baker DM, Jones JA, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS et al. Taurolidine peritoneal lavage as

is found in the abdomen. Its use, however, for the clean or prophylaxis against infection after elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 1994;

clean/contaminated abdomen appears to be based on habit 81: 1054–6.

and is hard to justify when the evidence is so conflicting. 15. Lawson KJ, Lavery I. Hydrogen peroxide vs normal saline lavage in experimental

The same is also true for IOPL for cancer. The evidence fecal peritonitis. Cleve Clin J Med 1987; 54: 279–84.

for tumour lysis, well proved in the in vitro model, has not 16. Dees J. A valuable adjunct to perforated appendices. Miss Doc 1940; 18:

been subjected to a rigorous randomised trial. This study 215–7.

highlights the variation in practice and hence the correct 17. Scherr D, Dodd T. Brief exposure of bacteria to topical antibiotics. Surg

indications for IOPL remain unresolved. Gynecol Obstet 1973; 17: 87–90.

18. Krukowski ZH, Koruth NM, Matheson NA. Antibiotic lavage in emergency sur-

References gery for peritoneal sepsis. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1986; 31: 1–6.

1. Schein M, Saadia R, Decker G. Intraoperative peritoneal lavage. Surg Gynecol 19. Noon G, Beall A, Jordan G et al. Clinical evaluation of peritoneal irrigation with

Obstet 1988; 166: 187–95. antibiotic solution. Surgery 1967; 62: 73–8.

2. JP. Surgical intervention in cases of general peritonitis. Proc Phil County Med 20. Silverman SH, Ambrose NS, Youngs DJ, Shepherd AF, Roberts AP, Keighley

Soc 1905; 26: 192–4. MR. The effect of peritoneal lavage with tetracycline solution on postoperative

3. King J. The treatment of peritonitis using peritoneal lavage. Ann Surg 1957; infection. A prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 1986;

145: 675–82. 29: 165–9.

4. Cope Z. Pioneers in Acute Abdominal Surgery. London: Oxford Medical 21. Schein M, Gecelter G, Freinkel W, Gerding H, Becker PJ. Peritoneal lavage in

Publication, 1938. abdominal sepsis. A controlled clinical study. Arch Surg 1990; 125: 1132–5.

5. Deaver J. The diagnosis and treatment of peritonitis of the upper abdomen. 22. Platell C, Cooper D, Hall JC. A meta-analysis of peritoneal lavage for acute pan-

Boston Med Surg 1910; 162: 485–90. creatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16: 689–93.

6. Moynihan B. Abdominal Operations. London: WB Saunders, 1926: 113. 23. Umpleby HC, Fermor B, Symes MO, Williamson RC. Viability of exfoliated col-

7. Rosenheim N, Blacke D, McIntyre P et al. The effect of volume on the distribution of orectal carcinoma cells. Br J Surg 1984; 71: 659–63.

substances instilled into the peritoneal cavity. Gynecol Oncol 1978; 6: 106–10. 24. Yu SK, Cohn Jr I. Tumor implantation on colon mucosa. Arch Surg 1968; 96:

8. Minervini S, Bentley S, Youngs D, Alexander-Williams J, Burdon DW, Keighley 956–8.

MR. Prophylactic saline peritoneal lavage in elective colorectal operations. Dis 25. Gertsch P, Baer HU, Kraft R, Maddern GJ, Altermatt HJ. Malignant cells are

Colon Rectum 1980; 23: 392–4. collected on circular staplers. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 238–41.

9. Hunt JL. Generalized peritonitis. To irrigate or not to irrigate the abdominal cav- 26. Sayfan J, Averbuch F, Koltun L, Benyamin N. Effect of rectal stump washout on

ity. Arch Surg 1982; 117: 209–12. the presence of free malignant cells in the rectum during anterior resection for

10. Platt J, Jones RA, Bucknall RA. Intraperitoneal antiseptics in experimental bac- rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1710–2.

terial peritonitis. Br J Surg 1984; 71: 626–8. 27. Jenner DC, de Boer WB, Clarke G, Levitt MD. Rectal washout eliminates exfoli-

11. Sindelar WF, Mason GR. Intraperitoneal irrigation with povidone-iodine solution ated malignant cells. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1432–4.

or the prevention of intra-abdominal abscesses in the bacterially contaminated 28. Basha G, Penninckx F, Mebis J, Filez L, Geboes K, Yap P. Local and systemic

abdomen. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1979; 148: 409–11. effects of intraoperative whole-colon washout with 5 per cent povidone-iodine.

12. Vallance S, Waldron R. Antiseptic vs. saline lavage in purulent and faecal peri- Br J Surg 1999; 86: 219–26.

tonitis. J Hosp Infect 1985; 6 (Suppl A): 87–91. 29. Docherty JG, McGregor JR, Purdie CA, Galloway DJ, O’Dwyer PJ. Efficacy of

13. Browne MK. Antibiotic lavage for peritonitis. BMJ 1979; 2: 1004–5. tumoricidal agents in vitro and in vivo. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1050–2.

258 Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 255–8

View publication stats

You might also like

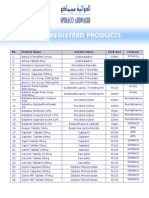

- Registerd Product of SPIMACO.Document6 pagesRegisterd Product of SPIMACO.Ahmad AlshewaymanNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Project Report-Sanjitkumar Vaghel Enrollment No030301006Document66 pagesSummer Internship Project Report-Sanjitkumar Vaghel Enrollment No030301006Sanjit M Vaghel50% (2)

- Cutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseDocument6 pagesCutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseRhian BrimbleNo ratings yet

- Notes Clinicalreview PDFDocument8 pagesNotes Clinicalreview PDFLuthie SinghNo ratings yet

- UrogynaecologiDocument6 pagesUrogynaecologir_ayuNo ratings yet

- Bilas LambungDocument12 pagesBilas LambungNthie UnguNo ratings yet

- Role of Open Surgical Drainage or Aspiration in Management of Amoebic Liver AbscessDocument9 pagesRole of Open Surgical Drainage or Aspiration in Management of Amoebic Liver AbscessIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Measure BUN Creat Urine LeakageDocument4 pagesMeasure BUN Creat Urine Leakagerendi wibowoNo ratings yet

- 43 Iajps43052018 PDFDocument6 pages43 Iajps43052018 PDFiajpsNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Postpartum Urinary Retention A Case RepoDocument3 pagesProlonged Postpartum Urinary Retention A Case RepoeeeNo ratings yet

- General Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueDocument3 pagesGeneral Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueRahul SinghNo ratings yet

- Oral Rehydration Therapy For Preoperative Fluid and Electrolyte Man-AgementDocument9 pagesOral Rehydration Therapy For Preoperative Fluid and Electrolyte Man-AgementSasmira JamalNo ratings yet

- 296 1179 1 PBDocument2 pages296 1179 1 PBKriti KumariNo ratings yet

- Subtotal Versus Total Abdominal Hysterectomy Randmoized Clinial Trial With 14-Year Questionnaire Follow UpDocument54 pagesSubtotal Versus Total Abdominal Hysterectomy Randmoized Clinial Trial With 14-Year Questionnaire Follow UpJoe HoroNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument12 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofFarizka Dwinda HNo ratings yet

- Perforated Peptic Ulcer - An Update: ArticleDocument14 pagesPerforated Peptic Ulcer - An Update: ArticleMuhammad ibnu kaesar PurbaNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical SciencesDocument6 pagesPharmaceutical SciencesiajpsNo ratings yet

- 08 Re-LaparotomyaftercesareanDocument8 pages08 Re-LaparotomyaftercesareanFarhanNo ratings yet

- Bladder Explosion During Transurethral Resection Surgery Case SeriesDocument21 pagesBladder Explosion During Transurethral Resection Surgery Case SeriesAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Reoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDocument8 pagesReoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDiego Andres VasquezNo ratings yet

- Primary Abdominal Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report: Cases Journal August 2009Document5 pagesPrimary Abdominal Ectopic Pregnancy: A Case Report: Cases Journal August 2009Sha AbdulaNo ratings yet

- Extended Left Colon ResectionsDocument4 pagesExtended Left Colon ResectionsAndreeaPopescuNo ratings yet

- Reducing Blood Loss at Open Myomectomy Using Triple Tourniquets: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesReducing Blood Loss at Open Myomectomy Using Triple Tourniquets: A Randomised Controlled TrialAlrick GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Positioning The Instillation of Contrast Cystography: Does It Provide Any Clinical Benefit?Document17 pagesPositioning The Instillation of Contrast Cystography: Does It Provide Any Clinical Benefit?Indah GitaswariNo ratings yet

- Moberg 2007Document5 pagesMoberg 2007Julio Adan Campos BadilloNo ratings yet

- Role of Imaging in Clinical Islet TransplantationDocument15 pagesRole of Imaging in Clinical Islet TransplantationR BNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3Document3 pagesJurnal 3Ega Gumilang SugiartoNo ratings yet

- Amilaze PredictivDocument7 pagesAmilaze PredictivDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Laplant 2018Document14 pagesLaplant 2018AndikaNo ratings yet

- Safe CholecystectomyDocument60 pagesSafe CholecystectomyCarlos Reyes100% (1)

- Complicationsoflapmyomectomy ANZ 2010Document7 pagesComplicationsoflapmyomectomy ANZ 2010Nadila 01No ratings yet

- Haemodialysis Adequacy-2Document73 pagesHaemodialysis Adequacy-2Nining KurniasihNo ratings yet

- Corto y Largo PlazoDocument6 pagesCorto y Largo PlazoElard Paredes MacedoNo ratings yet

- Acute Intestinal ObstructionDocument9 pagesAcute Intestinal ObstructionRoxana ElenaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Gallbladder Content Spillage in Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDocument18 pagesEvaluation of Gallbladder Content Spillage in Laparoscopic CholecystectomyIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Turkey: A Review of 5,000 CasesDocument2 pagesUpper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Turkey: A Review of 5,000 CasesEnderson MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Clinical Profile, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Management of Pyogenic Liver AbscessDocument11 pagesClinical Profile, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Management of Pyogenic Liver AbscessIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Mormont - Marked 24-h Rest Activity Rhythms Are Associated With Better Quality of LifeDocument9 pagesMormont - Marked 24-h Rest Activity Rhythms Are Associated With Better Quality of LifeFernandoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 Mainal malikNo ratings yet

- Five-Year Follow Up of A Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Subtotal With Total Abdominal HysterectomyDocument7 pagesFive-Year Follow Up of A Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Subtotal With Total Abdominal Hysterectomyjhon heriansyahNo ratings yet

- Do We Need Anorectal Physiology Work Up in The Daily Colorectal Praxis?Document6 pagesDo We Need Anorectal Physiology Work Up in The Daily Colorectal Praxis?soudrackNo ratings yet

- Red Cell Transfusion: Blood Transfusion and The AnaesthetistDocument20 pagesRed Cell Transfusion: Blood Transfusion and The AnaesthetistDesi OktarianaNo ratings yet

- Fluid Management in Extensive Liposuction A.37Document9 pagesFluid Management in Extensive Liposuction A.37Juan Esteban Hernandez SantamariaNo ratings yet

- EN Differences in The Effect of Using SteriDocument6 pagesEN Differences in The Effect of Using SteriZaki HafizNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?Document4 pagesPattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?neildamiNo ratings yet

- Jenis Jenis LukaDocument4 pagesJenis Jenis LukaMuchtar RezaNo ratings yet

- Appendiceal Mass: Is Interval Appendicectomy "Something of The Past"?Document4 pagesAppendiceal Mass: Is Interval Appendicectomy "Something of The Past"?galihmuchlishermawanNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy:An Experience of 200 Cases: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesLaparoscopic Cholecystectomy:An Experience of 200 Cases: Original ArticleAndrei GheorghitaNo ratings yet

- Hydrostatic Reduction of Intussusception in Children - A Single Centre ExperienceDocument9 pagesHydrostatic Reduction of Intussusception in Children - A Single Centre ExperienceMostafa MosbehNo ratings yet

- Annals of Medicine and Surgery: Case ReportDocument4 pagesAnnals of Medicine and Surgery: Case ReportDimas ErlanggaNo ratings yet

- Complicated Parapneumonic Effusion and Empyema Thoracis: Microbiology and Predictors of Adverse OutcomesDocument9 pagesComplicated Parapneumonic Effusion and Empyema Thoracis: Microbiology and Predictors of Adverse OutcomesabhikanjeNo ratings yet

- Article 1615981002 PDFDocument3 pagesArticle 1615981002 PDFMaria Lyn Ocariza ArandiaNo ratings yet

- XX Rru-11-269Document8 pagesXX Rru-11-269Ashwin KumarNo ratings yet

- Brunner's Gland Adenoma: Case ReportDocument3 pagesBrunner's Gland Adenoma: Case ReportasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Biloma After Cholecystectomy 2Document5 pagesBiloma After Cholecystectomy 2Rashid LatifNo ratings yet

- Medical Doctors Practice Regarding The Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Management at Mohammed Salih Edris Bleeding CenterDocument7 pagesMedical Doctors Practice Regarding The Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Management at Mohammed Salih Edris Bleeding CenterInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Conventional Versus Laparoscopic Surgery For Acute AppendicitisDocument4 pagesConventional Versus Laparoscopic Surgery For Acute AppendicitisAna Luiza MatosNo ratings yet

- Complications of Ovariohysterectomy and Orchiectomy in Companion AnimalsDocument17 pagesComplications of Ovariohysterectomy and Orchiectomy in Companion AnimalsCarolina Soler GómezNo ratings yet

- GALAinpregnancyDocument6 pagesGALAinpregnancyumar faruqiNo ratings yet

- Sultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsDocument25 pagesSultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsMikhail NurhariNo ratings yet

- Isolated Hepatocytes: Preparation, Properties and Applications: Preparation, Properties and ApplicationsFrom EverandIsolated Hepatocytes: Preparation, Properties and Applications: Preparation, Properties and ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) : This Document Is Downloaded At: 2013-07-02 08:34:41 CSTDocument15 pagesSEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) : This Document Is Downloaded At: 2013-07-02 08:34:41 CSTAndi MuhammadNo ratings yet

- DIR BF Antiseptics and Sterilization MethodsDocument2 pagesDIR BF Antiseptics and Sterilization MethodsLaura GarciaNo ratings yet

- Consideration of Povidone-Iodine As A Public Health Intervention For COVID-19Document3 pagesConsideration of Povidone-Iodine As A Public Health Intervention For COVID-19Anil KumarNo ratings yet

- 06 - June RsmitalagaDocument61 pages06 - June RsmitalagaJZik SibalNo ratings yet

- Povidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisDocument4 pagesPovidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisNur AjiNo ratings yet

- Home Treatment For Mild Shell Rot in TurtlesDocument3 pagesHome Treatment For Mild Shell Rot in TurtlesSa'ad Abd Ar RafieNo ratings yet

- ChlorhexidineDocument46 pagesChlorhexidineGabrielle Nicole Cruz LimlengcoNo ratings yet

- Lacey 1979Document7 pagesLacey 1979ABDO ELJANo ratings yet

- SazalDocument24 pagesSazalRAGHU NATH KARMAKERNo ratings yet

- Communicable Disease Nursing Part I IntroductionDocument5 pagesCommunicable Disease Nursing Part I Introductionchelljynxie100% (4)

- 02 - Asepsis and AntisepsisDocument31 pages02 - Asepsis and AntisepsisFirst ImpactNo ratings yet

- Persediaan 2017, 2018Document1,061 pagesPersediaan 2017, 2018Selly RianiNo ratings yet

- HOPE 1 - Q1 - W9 - Mod9Document12 pagesHOPE 1 - Q1 - W9 - Mod9Donajei RicaNo ratings yet

- Biocides in Antiseptics and SoapsDocument41 pagesBiocides in Antiseptics and SoapsSérgio - ATC do BrasilNo ratings yet

- Betadine GargleDocument2 pagesBetadine GargleTerry Mae Atilazal SarciaNo ratings yet

- PovidoneDocument2 pagesPovidoneElizabeth WalshNo ratings yet

- 03 030744e PVP Iodine GradesDocument20 pages03 030744e PVP Iodine Gradesdipakrussia0% (1)

- My SeminarDocument52 pagesMy SeminarvinnycoolbuddyNo ratings yet

- Ypf Alkes 25052023Document8 pagesYpf Alkes 25052023Jihad MalikNo ratings yet

- Betadine Douche - Google Search PDFDocument1 pageBetadine Douche - Google Search PDFIgn Haryo SusenoNo ratings yet

- 5 - AntiseptikDocument2 pages5 - AntiseptikAlifia Nur RizkiNo ratings yet

- List of Common MedicinesDocument2 pagesList of Common MedicinesDianne Macaraig100% (2)

- Analytical Survival STOMP II FAKDocument6 pagesAnalytical Survival STOMP II FAKme mineNo ratings yet

- Wound Cleansing Solution OptionsDocument2 pagesWound Cleansing Solution Optionsronique reidNo ratings yet

- Detrox, DisinfectantDocument67 pagesDetrox, Disinfectantsumiya mashadiNo ratings yet

- Basic Load (Individual) Veterinarian Field PackDocument3 pagesBasic Load (Individual) Veterinarian Field PackJohn MillerNo ratings yet

- 6 Sept 23 LKDocument178 pages6 Sept 23 LKDurrah Zati YumnaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Diagnosis Planning Implementation Rationale EvaluationDocument11 pagesAssessment Diagnosis Planning Implementation Rationale EvaluationYzel Vasquez AdavanNo ratings yet