Professional Documents

Culture Documents

743

743

Uploaded by

ashCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

743

743

Uploaded by

ashCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/14450276

CT differentiation of tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcinomatosis

Article in American Journal of Roentgenology · October 1996

DOI: 10.2214/ajr.167.3.8751693 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

134 753

8 authors, including:

Illsun Jung Moon-Soon Lee

Soongsil University Chungbuk National University

14 PUBLICATIONS 349 CITATIONS 253 PUBLICATIONS 5,074 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Young Kim Pyo Nyun Kim

University of Massachusetts Medical School Asan Medical Center

45 PUBLICATIONS 956 CITATIONS 250 PUBLICATIONS 6,239 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Budd Chiari Syndrome Field Study View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Pyo Nyun Kim on 05 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

CT Differentiation of Tuberculous

Peritonitis and Peritoneal

Carcinomatosis

Hyun Kwon Ha1 OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this study was to determine the potential of CT for distin-

Jung rnJung2 guishing tuberculous peritonitis from peritoneal carcinomatosis in I 35 clinically or patholog-

Moo Song Lee3 ically proven cases.

Byung GilChoi2 MATERIALS AND METHODS. Abdominal CT scans in 135 patients of tuberculous

Moon-Gyu Lee1 peritonitis (ii = 42) and peritoneal carcinomatosis (ii = 93) with documented omental, mesen-

Young Hwan Kim1 teric. or peritoneal pathology were retrospectively reviewed. CT findings were evaluated in

Pyo Nyun Kim1 each group of patients for the morphologic appearance of mesenteric or omental abnormali-

Yong HoAuh1 ties as well as for visualization of the spleen and liver. the lymph nodes, and ascites. Statisti-

cal comparisons using multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed to adjust for

the differences in CT findings between the two groups.

RESULTS. Mesenteric changes were more commonly seen in patients with tuberculous

peritonitis (98%) than in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (70%) (p < .01). Micronod-

ules (less than 5 mm in diameter) were noted in approximately one halfofpatients with tuber-

culous peritonitis or peritoneal carcinomatosis. but macronodules (5 mm in diameter) were

much more frequently seen in patients with tuberculous peritonitis (52%) than in patients

with peritoneal carcinomatosis (12%) (p < . 01). The omentum appeared to be more irregu-

larly infiltrated in peritoneal carcinomatosis patients (p < .01 ). The thin omental line covering

the infiltrated omentum was seen in 13 patients with tuberculous peritonitis but in only four

patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (p < .01 ). In peritoneal or extraperitoneal masses in

patients with tuberculous peritonitis. a low-density center was seen in I 8 cases (43%) and cal-

cification was noted in six cases ( 14%). The prevalences of splenomegaly and splenic calcifi-

cation were higher in patients with tuberculous peritonitis. Using multivariate analysis, we

calculated the sensitivity of CT for predicting tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcino-

matosis as 69% and 9 1%, respectively.

CONCLUSION. Although most CT findings that we analyzed overlap these diseases,

using a combination of CT findings increased our ability to distinguish tuberculous peritonitis

from peritoneal carcinomatosis.

T ubereulou.s

reduced

infection

in incidence

has been

but still remains

greatly matosis

overlap

is difficult

of imaging

or impossible

findings.

because

However,

of an

until

a persistent problem in endemic recently many researchers have described van-

Received April 21, 1995; accepted after revision April 8, 1996. areas or in immunocompromised patients. ous CT findings separately for each disease

1 Department of Radiology, Asan Medical Center, University Although in many instances tuberculous perito- entity [2-61. and compansn studies of both

of Ulsan Medical College, 388-1 Poongnap-Dong Sonpa-Ku, nitis can be diagnosed clinically and radiologi- diseases are limited. If a clear separation

Seoul 138-040, Korea. Address correspondence to H. K. Ha.

cally. a difficulty is encountered in patients between these diseases can be made. invasive

2Department of Radiology, St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic who lack typical symptoms and laboratory data studies, such as peritoneoscopy or exploratory

University Medical College, Seoul 137-701, Korea.

or whose chest films are normal, thus often laparotomy, might no longer be needed to con-

3Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan

mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis I I 1. If firm the diagnosis. The purpose of this study

Medical College, Seoul 138-040, Korea.

there is diffuse infiltration of the peritoneum. was to determine the potential of CT for distin-

AJR 1996;167:743-748

omentum, or mesentery with no suggestion of guishing tuberculous peritonitis from perito-

0361-803X19611673-743 primary tumor on CT, distinguishing between neal carcinomatosis in 135 clinically or

© American Roentgen Ray Society tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcino- pathologically proven cases.

AJR:167, September 1996 743

Ha et al.

Materials and Methods undetermined origin. Penitoneal carcinomatosis or its main branches. Splenoniegaly was defined as

In reviewing the medical records of patients was confirmed by laparotomy or laparoscopy (a = a spleen equal to or greater than 13 cm 71. The

who presented with tuberculous peritonitis 42) and paracentesis or aspiration biopsy (,i = 51). assessment of these findings was binary. and we did

between March 1991 and February 1994, we At surgery, widespread implantation of miliary not attempt to quantify the severity.

selected for analysis 42 patients who showed defi- tumor nodules was frequently found covering the Statistical qualitative and quantitative differ-

nite ornental, mesentenic. or penitoneal changes on serosal surfaces of the viscera. Paracentesis often ences in CT findings between the two groups were

CT scans and whose diagnoses were pathologically yielded a straw-colored or bloody fluid. analyied using Fisher’s exact test. Then, using a

or clinically proved as tuberculous peritonitis. Dur- CT was performed on commercially available software prograni (SAS Institute. Cary, NC). we

ing the same period. we also collected records of equipment (Somatom Plus-S: Siemens, Erland, performed a multivariate logistic regression analy-

93 consecutive patients with pathologically proven Germany, or GE Quick System; General Electric, sis 181 to determine which paranieters were useful

penitoneal carcinornatosis and obvious peritoneal Milwaukee, WI) using five, eight, or 10 slices at 8-, for distinguishing tuberculous peritonitis froni

disease on CT. No cases had both tuberculous pen- 10-, or 15-mm intervals from the dome of the dia- penitoneal carcinomatosis. Thereafter. the proba-

tonitis and pentoneal carcinornatosis concurrently. phragm to the symphysis pubis. The patients rou- bility of tuberculous peritonitis could be calculated

Clinical charts and surgical or pathologic findings tinely received oral and IV contrast material. The for each patient. With these data, the accuracy of

were also reviewed for each case. IV contrast medium, iopamidol (lopamiro 300; CT for predicting tuherculous peritonitis or perito-

The 42 patients with tuberculous peritonitis Bracco. Milano, Italy), was administered as a beilus neal carcinomatosis was obtained.

were between 8 and 74 years old (mean, 37 years followed by rapid drip infusion. CT scans of both

old); I 8 were men, and 24 were women. Of these groups were reviewed independently by two expeni-

patients. 14 were confirmed to have gastrointesti- enced radiologists; these observers were unaware of Results

nal tract involvement. and 29 had pulmonary the final diagnosis. CT scans in both groups were Mesentery

tuberculosis. No patients had a history of IV drug evaluated in random order. When interpretations

abuse or AIDS. The diagnoses were established by differed, a third radiologist reviewed the cases and The most conimon niesenteric changes

pathologic analyses obtained from laparotomy. majority opinion was used for a final decision. CT noted on CT included micronodular or macro-

laparoscopy. or fine-needle aspiration biopsy (ii = findings were compared for the morphologic nodular lesions, thickening of the mesentenic

30) or by improvement seen on abdominal CT appearance of mesenteric or omental abnormalities leaves (Fig. I ). and loss of normal mesentenic

studies following prescribed antituberculous che- as well as for visualization of the spleen and liver, configuration in both diseases. These mesen-

rnotherapy (a = 12). Of these 42 patients, 27 had the lymph nodes, and ascites. Mesentenic nodules tenic abnormalities were niore frequently seen

the wet form and I 5 had the dry form of tubercu- were divided into micronodular (less than 5 mm)

in patients with tuberculous peritonitis (98Ck)

bus peritonitis. In the patients who underwent sur- and macronodular (5 mm) forms, and loss of the

than in those with penitoneal carcinomatosis

gery. the wet form was associated with ascites of a normal configuration of the mesentery was mdi-

(70%) (/) < .01 ) (Table I).

yellowish turbid color, whereas the dry form cated when the mesentery showed an admixture of

soft-tissue densities, fluid densities, bowel

Micronodules (Fig. 2 were noted in 52% of

showed firmly matted intestine covered by a and

fibninous exudate. Also, visceral and panietal peri- loops. Omental pathology was divided into nodular patients with tuberculous peritonitis or penito-

toneal surfaces became studded with rniliary (presence of nodular masses). smudged (infiltration neal carcinomatosis (Table 2), whereas macro-

tubercles. The omenturn, which was usually in- with ill-defined lesions), or caked (soft-tissue nodules were seen in 22 (52C/ ) of the tubercu-

volved, was greatly thickened. Pathologic diagno- replacement) forms based on morphologic appear- bus peritonitis patients and I I ( I 2C/ ) of the

sis was made by observing caseating necrosis on ance. The omentum was considered to be smoothly penitoneal carcinoriiatosis patients (p < .01 ). For

the specimen and by culturing Mvcobacteriu,n thickened when the infiltrated omentum had a tumors that showed macronodules in penitoneal

tubereulo.s’is from the ascitic fluid or lymph nodes smooth border or showed a smooth transition from carcinomatosis patients. the origin was the

or by penitoneal biopsy. thick to thin portions; the omentum was considered

stomach in five, the rectum in one, the bile duct

The 93 patients with penitoneal carcinomatosis irregularly thickened when showing an irregular

in one, the uterus in one. the ovary in one, the

were between 19 and 89 years old (mean, 51 years border. The attenuation of the a.scites was compared

breast in one. and the lung in one. The macro-

old); 49 were men. and 44 were women. Patho- with fluid density of the gallbladder. renal cyst. or

logic proof of the primary tumor was available in bowel if not opacified with oral contrast agent. Loc- nodules seen in 22 of the tuberculous peritonitis

all cases; tumor origins were ovary in 31 patients, ulated ascites was defined as a localized, often patients had low-density centers in I 5 patients

stomach in 29, colon in eight, bile duct in five, round or oval fluid collection with mass effect. (Fig. 3). uniformly sized lesions in I 3 patients.

pancreas in five. uterus in three. liver in two, small Lymphadenopathy at unusual sites meant lymphad- and calcification in three patients.

intestine in two, and breast in two; six were of enopathy that did not follow the course of the aorta

Fig. 1.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 62-year-old wom- Fig. 2.-Peritoneal carcinomatosis due to cholangiocar- Fig. 3.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 24-year-old wom-

an. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows thin lines cinoma in 43-year-old man. Contrast-enhanced CT scan an. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows macronodular

(arrows) along course of mesenteric vessels, repre- shows micronodular type of peritoneal tumor seeding type of masses (ml with low-density centers and

senting thickened mesenteric leaves. (arrows) and nodular implants (arrowheads) on parietal thickened peripheral wall. Also note tiny calcifications

peritoneum. Note large amount of ascites present. (arrows) in some masses.

744 AJR167, September 1996

CT Differentiation of Tuberculous Peritonitis and Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

normalities on CT scans, whereas these

#{149}F±i:1P Patterns of M...nterlc Changss

abnormalities were present in 12 patients

. . Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis with peritoneal carcinomatosis (13%) (p <

Finding

(n=42) (n=93)

.05). These findings in both groups are

Mesenteric changes 98% (41/42) 70% (65/93) <.01 shown in Table 5. Of the five patients with

Nodule 93% (38/41) 91% (59/65) NS tuberculous peritonitis who had hypodense

Thickening 44% (18/41) 20% (13/65) <.05 splenic masses (size range, 0.8-I .6 cm)

Loss of nor mal configuration 7% (3/41) 5% (3/65) NS (Fig. 7), three of the masses were pathologi-

Note.-NS = not significant cally or clinically proven; two were con-

firmed at surgery; and one had improved by

the time of follow-up CT. Six patients with

c Nodul.. peritoneal carcinomatosis also had hypo-

dense masses (size range, 1 .0-6.0 cm), two

Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Find ing of which were multilocular in appearance;

(n=42) (n=93)

although pathologic confirmation was not

Micronodulea 52% (22/42) 52% (48/93) NS

made for these lesions, they were considered

Macronoduleb 52% (22/42) 12% (11/93) <.01 to represent metastatic lesions from primary

Cysticc 68% (15/22) 18% (2/11) <.05

tumors at other sites (four ovarian tumors,

Solid 32% (7/22) 82% (9/1 1) <.05 one rectal carcinoma, one of unknown ori-

Uniform 59% (13/22) 18% (2111) <.05 gin) because none of these lesions was seen

Variable 41% (9/22) 82% (9/11) <.05 on initial CT scans. The splenomegaly in six

Calcificationd 14% (3/22) 0% (0/11) NS patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis was

Note.-NS not significant

due to underlying liver cirrhosis or chronic

Micronodule: <5mm. hepatitis. In our series, hepatic involvement

bMacronodule: 5mm.

was not as frequent as splenic involvement

CCystic represents a mass with a low-density center and was seen in 18 patients (43%) with tuberculous peritonitis when

in patients with tuberculous peritonitis; only

including both peritoneal and extraperitoneal masses.

dCalcifications were also noted in enlarged lymph nodes at other sites in three patients. three such patients showed tiny parenchy-

mal calcifications.

Omentum dial region (Fig. 8); two of the nine patients. in Ascites

Omental abnormalities were noted in 26 the paravertebral region; and the remaining two Ascites was present in 27 patients with tuber-

patients (62%) with tuberculous peritonitis and patients. in the iliopsoas compartment. All 10 culous peritonitis (64%) and in 78 patients with

in 80 patients (86%) with peritoneal carcinoma- patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis had petitoneal carcinomatosis(M%)(p < .05) (Table

tosis (p < .01) (Table 3). Smudged omentum involvement of the pericardial nodes. No 6). The distribution patterns and the attenuation

was the most common pattern of infiltration in patients with paravertebral or iliopsoas nodal ofthe ascites did not significantly differ between

both groups, although omental cake (Figs. 4 and involvement exhibited concomitant spinal in- the two groups (Fig. 9). However, fluid accumu-

5) was more common in patients with pento- volvement. In addition, calcifications within lation in the lesser sac occurred more frequently

neal carcinomatosis. The omentum was more enlarged lymph nodes were seen in five patients in the patients with pentoneal carcinomatosis (p

irregular (78% versus 19%) (p < .01) and with tuberculous peritonitis. < .05), but this finding is ofquestionable signifi-

thicker (2.6 cm versus I .7 cm) in patients with cance because the amount of ascites in the

Liver and Spleen patients with tuberculous peritonitis was less

pentoneal carcinomatosis than in patients with

tuberculous peritonitis. In addition, we found Thirteen of the 42 patients with tubercu- than the amount in patients with pentoneal carci-

that the thin fibrous wall (omental line) (Fig. 6) bus peritonitis (3 1%) showed splenic ab- nomatosis (p < .05).

covering the infiltrated omentum was much

more frequently seen in patients with tubercu-

bus peritonitis (50% versus 5%) (p < .01). l1i:1*Patterns ofOmsntal hangss . .

Lymph Node

. . Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Finding (n 42)

=

(n = 93) p

Peripancteatic lymph node involvement along

Omental changesa 62% (26/42) 86% (80/93) <.01

the branches of the celiac axis (Fig. 7) was seen

in 18 patients with tuberculous peritonitis Nodular 0% (0/26) 13% (10/80) NS

(43%) (Table 4); the degree of lymphadenopa- Smudged 92% (24/26) 68% (54/80) <.05

thy was minimal in nine patients and severe in Caked 8% (2/26) 20% (16/80) NS

the remaining nine, and two of the nine patients Thickness 1.7 cmb 2.6 cmb

with severe involvementdeveloped mild biliaty Smooth 81% (21/26) 20% (16/80) <.01

tree dilatation. We found no statistically signifi- Irregular 19% (5/26) 78% (62/80) <.01

cant differences between the two groups in the Omental line (+) 50% (13/26) 5% (4/80) <.01

prevalence oflymphadenopathy at unusual sites;

Note.-NS = not significant

five ofthe nine patients with tuberculous perito- a0nly the predominant finding was counted if different patterns coexisted.

nitis showed lymphadenopathy in the pencar- bMean maximum thickness.

AJR:167, September 1996 745

Ha et al.

Fig. 4.-Penitoneal carcinomatosis due to breast car- Fig. 5.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 30-year-old woman. Fig. 6.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 19-year-old worn-

cinoma in 58-year-old woman. Contrast-enhanced CT Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows omental cake an. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows thin densely

scan shows omental cake (solid arrows) with ascites. (arrows) and diffuse mesentenc infiltration with nodules enhancing peripheral rim (omental line) (arrowheads)

Parietal peritoneum (open arrow) is also thickened. and thickened leaves. Also note loculated intraperitoneal that covers omental infiltration. Ornentum also ap-

fluid collection (A) and diffuse peritoneal thickening. pears to be uniform in thickness.

Fig. 7.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 32-year-old man. Con- Fig. 8.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 8-year-old child. Fig. 9.-Tuberculous peritonitis in 50-year-old man.

trast-enhanced CT scan reveals partially calcified mass- Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows small masses Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows high-density as-

es (closed arrow) in region of portacaval space. Note (arrows) in penidiaphragmatic region. cites (A) in peritoneal cavity.

small hypodense mass (open arrow) in spleen, which

was surgically proven to be tuberculous granuloma.

Multivariate Analysis sidered. With these data, tuberculous peritoni- larity. Ifthe result is zero or greater, tubercu-

A model of multivariate logistic analysis tis was predicted in 29 of the 42 patients, for a bus peritonitis can be suggested.

was performed with the following variables: sensitivity of 69% (confidence intervals, 55-

omental irregularity; omental line; splenic ab- 83%), whereas peritoneal carcinomatosis was

predicted in 85 of 93 patients for a sensitivity Discussion

normalities, including splenomegaly or calcifi-

cation; and mesenteric macronodule (Table 7). of 91% (confidence intervals, 85-97%). CT has been chosen recently as a major

Statistical analysis system software estimated Instead of using the probability drawn diagnostic technique for diffuse or focal peri-

the values of the logistic regression coeffi- from the equation that we suggested. a sim- toneal diseases. However, CT still poses

cients included in the expression z = a + 1i. pie rule can also be used for differentiating problems, such as low sensitivity for detect-

where cx is an intercept term of logistic regres- the diseases. The rule is to add one point if a ing minimal peritoneal disease, especially

sion, 3 is the regression coefficients, and x is mesenteric macronodule is present, one for when the lesions are less than 1 cm in diame-

the value of the independent variables. The z splenic abnormality, and two for omental ter [9]. Also common are nonspecific find-

value can be obtained by using the data in line and to subtract two for omental irregu- ings in benign or malignant diseases [10].

Table 7: z = -0.98 - 2.59 (omental irregular-

ity) + 2.59 (omental line) + 166 (mesenteric

IViLymph Nod. Distribution

macronodule) + I .60 (splenic abnormality).

The probability of tuberculous peritonitis in . Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Site

each individual patient can be drawn from this (n=42) (n=93) p

equation: probability = eZ/( I + e7). To separate Pelvic 5% (2/42) 13% (12/93) NS

patients with tuberculous peritonitis from Celiaca 43% (18/42) 40% (37/93) NS

those with peritoneal carcinomatosis, the cut Paraaortic 60% (25/42) 38% (35/93) <.05

point was 0.5; if the predictive value was Unusualb 21% (9/42) 11% (10/93) NS

greater than 0.5. tuberculous peritonitis was

Note.-NS = not significant

considered, and if the predictive value was less 8Celiac represents the branches of the celiac axis.

bUnusual sites include the pericardial and paravertebral regions or the iliopsoas compartment.

than 0.5, peritoneal carcinomatosis was con-

746 AJR:167, September 1996

CT Differentiation of Tuberculous Peritonitis and Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

IVi:1Splenic Abnormality nocarcinoma of the ovary have been reported

to contain histologic calcification in approxi-

. . Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Finding mately 30% of cases because of psammoma

(n = 42) (n = 93) p

bodies [12].

Present 31% (13/42) 13% (12/93) <.05 The prevalence and patterns-that is, nod-

Splenomegaly 92% (12/13) 50% (6/12) <.05 ular, smudged, or caked-of omental abnor-

Mass 38% (5/13) 50% (6/12) NS malities were not significantly different in

Calcification 54% (7/13) 0% (0/12) <.01 either disease. Although omental cake was

Note.-NS = not significant. commonly seen in peritoneal carcinomatosis

in our and another study [ I 01, we observed

that this finding was not pathognomonic for

Patterns of Ascites this disease. Rather than analysis of omental

infiltration pattern. the observation of outer

. Tuberculous Peritonitis Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

(n=42) contour of the infiltrated omentum appeared

(n=93)

to be more valuable for differentiating both

64% (27/42) 84% (78/93) <.05

conditions; irregular thickening of the infil-

52% (14/27) 26% (20/78) <.05

trated omentum favored the diagnosis of peri-

48% (13/27) 74% (58178) <.05

toneal carcinomatosis. Interestingly, a thin

4% (1/27) 14% (11/78) NS

omental line, which is a fibrous wall covering

19% (5/27) 47% (37/78) <.05 the infiltrated omentum and is presumed to

15% (4/27) 15% (12/78) NS develop from a long-term chronic peritoneal

26% (7/27) 27% (21/78) NS process, was more common in patients with

Note.-NS = not significant. tuberculous peritonitis (p < .01); the reason

for the much lower occurrence of this finding

in peritoneal carcinomatosis may be that both

the nodular and the smudged patterns of infil-

oglsdc R.gr.sslon Analysis tration appear to be commonly replaced by

soft-tissue masses (omental cake) in the late

stage of this disease.

Peripancreatic lymph node involvement

along the branches ofthe celiac axis (43%) is a

well-recognized manifestation of abdominal

tuberculosis and reflects the distribution of

lymphatic drainage from the small bowel and

liver. When confined to these areas and adher-

Even though our series was confined to the detection of these lesions partially depends ent to the pancreas. the lymph nodes sometimes

advanced cases of obvious penitoneal dis- on the presence of ascites as well as on the simulate a primary pancreatic carcinoma. It is

ease, we achieved a high accuracy rate using location of the lesion. The presence of ascites also interesting to note that biliary tract obstruc-

multivaniate analysis of CT for distinguish- in more than two thirds of our patients may tion in such circumstances is rare despite the

ing between these two diseases. explain the high detection rate of micronod- severe degree of lymphadenopathy. as other

Our results showed that the prevalence of ules. researchers have also demonstrated [16, 17J. If

macronodules in the mesentery was uncom- The low-density center in the peritoneal the masses in these regions contain calcifica-

mon in penitoneal carcinomatosis. The com- masses has been regarded as one of the char- tions, tuberculosis may be the primary cause of

mon occurrence of mesentenic micro- or acteristic findings of abdominal tuberculosis a lesion. Although the prevalence of lymphade-

macronodules in tuberculous peritonitis [2, 4]. It was caused either by caseation nopathy at unusual sites did not differ signifi-

appears to be because tuberculous peritonitis necrosis or pus and was noted in I 8 (43%) of cantly between the two diseases, the

develops from the rupture of mesenteric the 42 patients when including peritoneal and involvement of paravertebral regions or the ili-

lymph nodes seeded by the hematogenous or extraperitoneal masses. However. this find- opsoas compartment seems to be rare in perito-

lymphatic routes from the primary lesion ing is not pathognomonic for tuberculosis neal carcinomatosis.

sites I 1 I I or direct spread from the serosa by because it can also be seen in Burkitt’s lym- The spleen has been reported to be com-

continuity from adjacent glands or structures: phoma I 14] or in treated lymphoma, meta- monly involved in tuberculosis secondary to

therefore. the mesentenic nodules seen on CT static malignancy. pyogenic abscess, or diffuse parenchymal involvement or as a non-

represent tubercles either in the lymph nodes Whipple’s disease [5, 15]. The calcifications specific response to infection: a high preva-

or on mesentenic surfaces. CT may not easily within macronodules in the mesentery or lence of splenomegaly was noted in I 8 of 27

detect micronodules on the mesentenic sun- enlarged lymph nodes at other sites, as seen cases of abdominal tuberculosis [2]. Because

face because of its inherent limitation for in six of our patients, favored the diagnosis miliary dissemination is a common form of

imaging such small lesions [9. 12]. However, of tuberculous infection, although peritoneal tuberculous involvement in the spleen. CT

as shown by other researchers [ I 31. CT tumor implants from primary serous cystade- may not detect these lesions ifcalcifications do

AJR 167, September 1996 747

Ha et al.

not develop; macronodular involvement of land, OH, for her editorial assistance in the 9. Silverman PM, Osborne M, Dunnick NR, Bandy

several centimeters rarely occurs in abdominal preparation of the manuscript. LC. CT prior to second-look operation in ovarian

cancer. AJR 1988:150:829-832

tuberculosis [18]. In addition, although the

10. Cooper C, Jeffrey RB, Silverman PM, Federle MR

spleen is an organ rarely affected by meta-

Chun GH. Computed tomography of omental

stases [19], our study showed that the presence References pathology. J ComputAssist Tomogr 1986;I0:62-66

of a splenic mass was not helpful in differenti- I . Nance FC. Disease of the peritoneum, retroperi- 1 1. Thoeni RF, Margulis AR. Gastrointestinal tuber-

ation of these diseases. toneum, mesentery. and omentum. tn: Haubrich culosis. Semin Roentgenol 1978:14:283-294

WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, eds. Bockus gastroen- 12. Mitchell DG, Hill MC, Hill 5, ZaloudekC. Serous car-

terology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1995: cinoma of the ovary: CT identification of metastatic

3061-3096 calcified implants. Radiology 1986;158:649-652

Conclusion

2. Hunlick DH, Megibow AJ, Naidich DP, Hilton S. 13. Burack WR, Hollister RM. Tuberculous peritoni-

We attempted to distinguish tuberculous Cho KC, Balthazar El. Abdominal tuberculosis: tis. Am J Med 1960; 28:510-523

peritonitis from peritoneal carcinomatosis on CT evaluation. Radiology 1985:157:199-204 14. Li DKD. Rennie CS. Abdominal computed tomog-

Cr. Although most of the findings analyzed 3. Hanson RD. Hunter TB. Tuberculous peritonitis: raphy in Whipple’s disease. J Comput Assist

overlap in both diseases, use of a combination CT appearance. AiR 1985:144:931-932 Tomogr 1980:4:630-633

of CT findings, that is, mesenteric macronod- 4. Epstein BM, Mann JH. CT of abdominal tubercu- 15. Krudy AG, Dunnick WR, Magrath IT, Shawker

losis. AiR 1982:139:861-866 TH, Doppman JL, Spiegel R. CT of American

ule, irregularity of the infiltrated omentum,

5. Walkey MM. Friedman AC, Sohotra P. Radecki Burkitt lymphoma. AiR 1981:136:747-754

omental line, or splenic abnormalities includ- PD. CT manifestations of peritoneal carcinomato- 16. Kohen MD, Altman KA. Jaundice due to a rare

ing splenomegaly or calcification, increases sis.AJR 1988:150:1035-1041 cause: tuberculous lymphadenitis. Am J Gastro-

the ability of CF to distinguish tuberculous 6. Jeffrey RB Jr. CT demonstration of peritoneal enterol 1973:59:48-53

peritonitis from peritoneal carcinomatosis. implants. AiR 1980:135:323-326 17. Murphy TF, Gray GE Biliary obstruction due to tuber-

7. Johnson PM, Spencer RP. The spleen. In: Free- culous lymphadenitis.AmJMed 10:68:452-4M

man LM, Johnson PM, eds. Clinical scintillation 18. Choi BI, Im JG, Han MC, Lee HS. Hepatosplenic

imaging. 2nd ed, New York: Grune & Stratton, tuberculosis with hypersplenism: CT evaluation.

Acknowledgment Gastminiest Radiol 1989:14:265-267

1975:639-670

We thank Bonnie Hami, Department of Radiol- 8. Hosmer DW Jr. Lemeshow 5, eds. Applied logis- 19. BergeT Splenic metastases: frequencies and patterns.

ogy. University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleve- tic regression. New York: Wiley, 1989:1-23 Acta PatholMicrobiolScand 1974:82:499-506

748 AJR:167, September 1996

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- What Are The Causes of Elevated TSH in A Newborn?: Clinical InquiriesDocument3 pagesWhat Are The Causes of Elevated TSH in A Newborn?: Clinical InquiriesalimNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation Peptic Ulcer: Ma. Christina T. Alvarez Wup - Bs Nursing Iii-2Document18 pagesCase Presentation Peptic Ulcer: Ma. Christina T. Alvarez Wup - Bs Nursing Iii-2Shane Aileen AngelesNo ratings yet

- Med ProjectDocument23 pagesMed Projectapi-527956594No ratings yet

- Pharmacogenetics 141110022651 Conversion Gate01Document45 pagesPharmacogenetics 141110022651 Conversion Gate01Jeevan Khanal0% (1)

- A Case Study Utilizing Vojta Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Therapy To Control Symptoms of A Chronic Migraine Sufferer 2011 Journal of Bodywork ADocument4 pagesA Case Study Utilizing Vojta Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Therapy To Control Symptoms of A Chronic Migraine Sufferer 2011 Journal of Bodywork AJose J.No ratings yet

- Medical Report PDFDocument1 pageMedical Report PDFCesar DsousaNo ratings yet

- PediatricsDocument87 pagesPediatricsCarlos HernándezNo ratings yet

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 DashboardDocument24 pagesMassachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 DashboardJohn WallerNo ratings yet

- OB OSCE ReviewerDocument5 pagesOB OSCE ReviewerPao Ali100% (1)

- Tumor Control After Palliative Hypofractionated Quad-Shot EBRT Followed by BrachytherapyDocument7 pagesTumor Control After Palliative Hypofractionated Quad-Shot EBRT Followed by Brachytherapynaya_kawaiiNo ratings yet

- ACCREDITED PEDIA ON Chong Hua Hospital Mandaue & Cancer CenterDocument6 pagesACCREDITED PEDIA ON Chong Hua Hospital Mandaue & Cancer CenterBrenna BiancaNo ratings yet

- Francis N. Ramirez, MDDocument9 pagesFrancis N. Ramirez, MDPridas GidNo ratings yet

- First Aid AssignmentDocument10 pagesFirst Aid AssignmentmusajamesNo ratings yet

- Aromasin 25 MG Coated Tablets SMPCDocument9 pagesAromasin 25 MG Coated Tablets SMPCpedjaljubaNo ratings yet

- Role of Vamana in The Management of Switra With Special Reference To Vitiligo Case StudyDocument3 pagesRole of Vamana in The Management of Switra With Special Reference To Vitiligo Case StudyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Health Manpower PlanningDocument7 pagesHealth Manpower PlanningAkash GoreNo ratings yet

- Idl 2021 MD 0265Document1 pageIdl 2021 MD 0265sfda.badrmedicalNo ratings yet

- Aisha TuDocument21 pagesAisha TuDedan GideonNo ratings yet

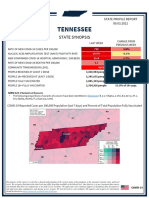

- Tennessee State Profile Report 20210903 PublicDocument17 pagesTennessee State Profile Report 20210903 PublicAnonymous GF8PPILW5No ratings yet

- Group 7 - Subgroup 2 Chief ComplaintDocument5 pagesGroup 7 - Subgroup 2 Chief ComplaintKAYLLIEN DURANNo ratings yet

- A Pilot Randomized Trial of Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbations Treatment StrategiesDocument51 pagesA Pilot Randomized Trial of Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbations Treatment StrategiesIuri NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Orthopaedics PunchDocument6 pagesOrthopaedics PunchHicham GawishNo ratings yet

- Ms II NCPDocument2 pagesMs II NCPABIL ABU BAKARNo ratings yet

- Criterios Beers 2019Document21 pagesCriterios Beers 2019Lissy TabordaNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda The Science of LifeDocument7 pagesAyurveda The Science of Lifecaptain490% (1)

- Uropathogen Resistance and Antibiotic Prophylaxis: A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesUropathogen Resistance and Antibiotic Prophylaxis: A Meta-AnalysisVijayakanth VijayakumarNo ratings yet

- Effect of Passive Smoking During Pregnancy On Birth Weight of NeonatesDocument3 pagesEffect of Passive Smoking During Pregnancy On Birth Weight of NeonatesMito JerickoNo ratings yet

- Phillips SWOTDocument9 pagesPhillips SWOTlinh_nd123No ratings yet

- Aggressive Periodontitis inDocument5 pagesAggressive Periodontitis inOctavian CiceuNo ratings yet

- UNIT II MedicalDocument34 pagesUNIT II Medicalangelax1.1No ratings yet