Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eliade Sacred Profane Intro and CH1 PDF

Eliade Sacred Profane Intro and CH1 PDF

Uploaded by

Timothy P0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views30 pagesOriginal Title

Eliade-Sacred-Profane-Intro-and-CH1.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views30 pagesEliade Sacred Profane Intro and CH1 PDF

Eliade Sacred Profane Intro and CH1 PDF

Uploaded by

Timothy PCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 30

THE

SACRED

AND

THE y

prorane

TIE NATURE OF RELIGION

by Mircea Eliade

‘Translated from the French

by Willard R. Trask

A Harvest Boole « Harcourt, Ine

Orowle Aas NowYrk Son Digs Teno London

The extraordinary interest aroused all over the

‘world by Rudolf Otto's Das Heilige (The Sacred), pub-

Tished in 1917, still persists, Its success was certainly

due to the author's new snd original point of view. Tn-

stead of studying the ideas of God and religion, Ovo

undertook to analyze the modalities of the religious

experience. Gifted with great psychological subtety, and

thoroughly prepared by his twofold training 28 theo-

logian and historian of religions, he succeeded in de-

termining the content and speciic characteristics of

religious experience. Passing over the rational and

‘speculative side of religion, he concentrated chiefly on

its irrational aspect. For Otto had read Luther wr ad

‘understood what the “living God” meant to a believer.

It was not the God of the philosophers—of Erasmus,

8

fo ample wa mt an eta hat en 4

tro morlepr,eearil poe a

Jin the divine wrath. re ied

In eli Ovo ethno dir he

certo hs fh taal eres

Hens eng of torr blr ha acre, ee

thewetnpng stn (wron emer),

sy (jt) al rent a orn

tony ef pee nt li fr elie

fecnane my (eyo fon) in wich

to fs of flyer Os Saracen al

"ccc mnie (hom a ume),

tetany on of op af

Chine poe Th unos post lng

“aly oe" (ge ode) eng aly wd

°

10 The Sere end he Frofone

totaly different. I i like nothing human oF cosmic

confronted with it, man senses his profound nothing-

pea, fels that he is ony a creature, or in the words in

‘which Abraham addressed the Lord, is “but dust and

ashes” (Genesis, 18, 27).

"The sacred always manifests itself as a reality of a

wholly different order from “natural” reais. Tt is

true that language naively expresses the tremendumy oF

the mojesas, othe mysterum fascinans by terms bore

rowed from the world of nature or from man's secular

‘meatal life But we know that this analogical terminol-

‘ogy is due precisely to human inability to expres the

‘ganz ender; all that goes beyond man’s natural expe-

renee, language is reduced to suggesting by terms taken

from that experience.

“After forty year, Ot's analyses have not lost their

value; readers ofthis book will profit by reading and

reflecting on them. But in the following pages we adopt

4 diferent perpestive. We propose to present the phe-

‘nomenon of the sacred in ll ts eomplexty, and not only

{nwo far siti irrational. What will concern us is not

the relation between the rational and nonrational ele-

ments of religion but the sacred in is entirety. The fst

‘pombe dfnition ofthe sacred is that it isthe opposite

ofthe profane. The aim ofthe following pages isto ills

trate and define this opposition between sacred and

profane,

Inuroducion ML

[WHEN THE SACRED MANIFESTS ITSELF

‘Man becomes aware of the sacred bocause it

sanifet isl, shows itself as something whelly differ-

ent from the profane. To designate the act of manifes-

tation of the sacred, we have proposed the term hiero-

hany. It is a Siting trm, bocause it does

anything further; it expresses no moro than i is

{nits etymological content, i. that something sacred

shous itself tows? Te could be said that the history of

religions—from the most primitive to the most highly

Aeveloped—is constituted by a great number of hieror

phanies, by manifestations of excred realities. From the

most elementary hierophany—e,, manifestation ofthe

‘acred in some ordinary abject, a stone or a tee—t0

the supreme hierophany (which, for a Christian, isthe

incarnation of God in Jesus Christ) there is no solution

of continuity. In each case we are confronted by the same

rysterious act—the manifestation of comeing of a

‘wholly diferent order, a reality that does not belong to

cour world, in objects that are an integral past of our

natural “profane” world.

‘The modern Occidental experiences a certain uneas-

ness before many manifestation ofthe sacred. He finds

itditicalt to accept the fact that, for many human beings,

the sacred can be manifesta in stones or tees, for

Ct Me id, Pate in Compra Raion Kaw Yi, Sed

{Ward GR pp. 7 Cd hear w Pater

12 The Sucred and the Profane

‘example. But as wo shall soon see, what is involved is

rot @ veneration ofthe stone in itself, a cult ofthe tree

in iteelf. The sacred txee, the sacred sione are not

adored as stone or tree; they aro worshipped precisely

Decause they are hierophanies, because they show some-

thing that is no longer stone or tree but the sacred, the

‘pons andere.

Tt is impossible to overemphasize the paradox repre-

sented by every hierophany, even the most elementary.

By manifesting the sacred, any object becomes something

else, yet it continues to remain itself, for it continues to

participate in its surrounding coemic milieu. A sacred

stone remains a stone; apparently (or, more precisely,

from the profane point of view), nothing distinguishes it

from all other stones. But for those to whom a stone

reveals itself as sacred, its immediate reality is trans

‘muted into a supernatural reality. In other words, for

those who have a religious experience all mature is

capable of revealing itself as cosmic sacrality. The

‘cosmos in ts entirety ean become a hierophany.

"The man ofthe archaie eoceties tends to live as much

‘as possible inthe sacred or in close proximity to com

secrated object. The tendeney is perfectly understand-

able, because, for primitives as for the man of all pre-

modem societies, the sacred is equivalent to a poter,

‘end, inthe last analysis to reality. Tho sacred is eaturated

‘with being. Saored power moans reality and at the same

time endutingness and eflcacity. The polarity sacred

Invodtion 18

‘profane is often expressed as an opposition between real

‘and unreal ox psoudoreal. (Naturally, we must not expect

to find the archaie languages in possession of this philo-

sophical terminology, real-unreal, ete; but we find the

thing.) Thus its easy to understand that religious man.

deeply desires to be, to participate in reality, to be satu

rated with power.

‘ur chicf concern in the following pages will be to

lucidate this subject—to show in what ways religions

‘man attempts to remain as long as possible in a sacred

universe, and honco what hia total experiance of life

‘proves to be in comparison with the experience of the

‘man without religious feeling, of the man who lives, or

‘wishes to live in a deeacralized world. It should be said

at once that the completely profane world, the whelly

ecacralizod cosmos, isa recent discovery inthe history

‘of the human eprit. It does not devolve upon us to show

by what historieal processes and as the result of what

changes in spiritual attitudes and behavior modern man

thas desacralized hie world and assumed a profane exist

fence. For our purpose it is enough to observe that

Aesacralization pervades the entre experience of the

‘nonreligious man of modern societies and that, in com

sequence, he finds it increasingly dificult to rediscover

the existential dimensions of religious man in the archaic

VA The Sacred and the Profane

‘two MopES OF BEING IN THE WORLD

“he syst vide the two models of emp

sionosneed an profane wil be appre when we

Sout dese eed pce ordeal building of

fhe human bbitaons othe veretin of tho rlgoas

‘paren of time, o he reltons of religous man to

aurea the world of tos, or the coseration of

mane fuels te sncraiy wit wich ms tal

fen (on yk a an be aa

Simply calling wo mind win the cy ote hous mata,

eer hve ume fr ner and nomaligons

wean wil howe ith to not vividness al that die

Angus such woman om @ an Delong 10 ay

trehae nocny or even fsm « pena af Chinn

Europe. For em conedowseay pysologeal act

PetMngy sas and sais in rom oly an oremnic

‘enomenon however chit ay al be encumbered

By tabu Cinporngy for execpt prwlar rules for

wating pepe” frig tome sean behavior

Shuapoved by total morality) Bat forthe pet,

Soc an acts never singly piyiloial i yore

mom a scromonts tht yeoman wit the

Te lize that sacred and pro-

"Tho wader wil ery soon rain that

fone avetro moses af bing in he wl, to existential

ane need by ta te our of Bs history.

‘Tuco mutes of being inthe world aze not of conern

Iniroduction 18

only to the history of religions or to sociology; they are

‘ot the object only of historical, sociological, or ethno-

logical stady. Inthe last analysis, the sacred and profane

modes of being depend upon the diflerent positions thet

rman has conquered in the cosmos; hence they are of

oncern both to the philosopher and to anyone seeking

to diseover tho possible dimensions of human existonce.

{is Sor this reseon that, though he ie a historian of

religions, the author of this book proposes not to enfine

himself only tothe perspective of his particular science.

‘Tho man of the traditional societies is admittedly a homo

religiosus, but his behavior forms part of the general

Ipchavior of mankind and hence is of eoncera ta philo-

sophical anthropology, to phenomenology, to peychol-

oy.

‘The better to bring out the specific charactoriatia of

1ife in a world capable of becoming sacred, I shall not

hesitate to cite examples from many religions belonging

to different periods and cultures. Nothing can tako the

place of the example, the concrete fact. Tt would be wse-

less to discuss the structure of sacred space without

showing, by particular examples, how such a space is

ceonetacted and why it becomes qualitatively different

from the profane space by which it is surrounded. I

shall select such examples from among the Mesopo-

tamians, the Indians, the Chines, the Kwakiutl and other

primitive peoples. From the historicocultural point of

view, such a juxtaposition of zeligious data pertaining

16 There nd the Profene

se far removed in time and pace i ot wie

‘ere danger. Fo thre slays the of falling

hak ino the eros ofthe nineeeth extry and, p=

‘Sealy, of believing with Tylor Frazer tat th

fenton ofthe buan do natzal phennmens is

Ahifore. But he progres scompised in earl ey

ogy and in the istry of religions bas shown tht

{Sie bot always tv, nt a's eins to nate

tre often conlitond by hs clare and ewe, fly,

hy iar. :

Bot the import hing fr ou prpse is bring

ut the opie characteristic of the religious e=p-

Snes: ratber than to show is merous vations and

{be diferencs cased by hioy. Ro womevhat si

inorder obtain a bter grap of the poate phenme-

to, we shld have recourse fo mats heterogeneous

‘Etnglen ends by ide with Homer an Dante, quote

inde, Chins, and Mexican poem; that soul tke

Int eideraon not only pete: pontng a histor-

{Sl common Jemoiaaor (Home, Vrg, Dass) but

loo cea tat ae dependent upon oie etic,

Fro the pit af vow of Ierarybiory, sch juste

positon ar tobe viewed wih suicion; but hey ae

Tall too jet isto dsr the pone plenomenon

uch i we prope fo chow te exeataldierece

Tewera poate language and th ataran language

of everyday ite

Iurotucéon AT

Our primary concern is to present the specie

dimensions of religious experience, to bring out the

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

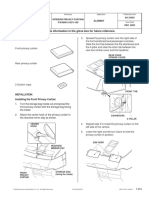

- Installation Instructions: Keep This Information in The Glove Box For Future ReferenceDocument5 pagesInstallation Instructions: Keep This Information in The Glove Box For Future ReferenceTimothy PNo ratings yet

- Installation Instructions: Keep This Information in The Glove Box For Future ReferenceDocument4 pagesInstallation Instructions: Keep This Information in The Glove Box For Future ReferenceTimothy PNo ratings yet

- Competition Schedule Seasa Ina 2019Document3 pagesCompetition Schedule Seasa Ina 2019Timothy PNo ratings yet

- Model Year 2001: Owners ManualDocument13 pagesModel Year 2001: Owners ManualTimothy PNo ratings yet

- Airgun Internal BallisticsDocument6 pagesAirgun Internal BallisticsTimothy PNo ratings yet