Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Provoked The Lex Porcia PDF

What Provoked The Lex Porcia PDF

Uploaded by

Stephanie WyleneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Provoked The Lex Porcia PDF

What Provoked The Lex Porcia PDF

Uploaded by

Stephanie WyleneCopyright:

Available Formats

What Provoked the Lex Porcia?

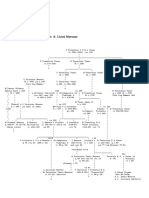

Arthur J. Wylene

In the Roman Republic, citizens enjoyed the right of provocatio, i.e., the right to

appeal to the people against punishments imposed by magistrates. While this right was

fundamental to Roman civil society - occupying a place similar to our Anglo-American

right to trial by jury - its origins and contours remain deeply controversial. One

particularly vexing question is whether, when, and how this right was extended to citizens

(and punishments) outside the city of Rome (typically defined as the area more than one

mile beyond the pomerium).

The traditional theory is that provocatio originally existed only within the city

limits of Rome (being tied to the tribunes' auxilium and the plebs self-help), but was later

extended to Italy and the provinces by a Lex Porcia carried by P. Porcius Laeca (either

during his praetorship in 195 or - more likely - his tribunate in 199). (See generally

Lintott, Provocatio. From the struggle of the orders to the Principate, ANRW I.2

(1972).) However, this is not universally accepted. Alternative theories range from the

posit that provocatio applied without geographic limit from its inception (Giovanni,

Consulare Imperium, 1983) to the hypothesis that it never legally applied outside the city.

(Greenidge, The 'Provocatio Militiae' and Provincial Jurisdiction (Classical Review,

1896) and The Porcian Coins and the Porcian Laws (Classical Review, 1897).)

Accepting that provocatio applied in the provinces (in any period) raises the difficult

subsidiary question of whether legionaries could appeal the sentences of their

commanders (to flogging, execution, or both). (See generally Nicolet, The World of the

Citizen in Republican Rome, p. 406 (1988).)

Heitland believed that all three Porcian laws (Cic. Rep. 2.54) concerned the

penalty of flogging, rather than provocatio proper. (M. Tulli Ciceronis pro C. Rabirio,

with notes by W.E. Heitland, pp. 100-108 (1882).) He explained the second of these laws,

by P. Porcius Laeca, as follows: "[T]he principal enactment of this law was the extension

of the privilege [against flogging] to all citizens living or carrying on civilian pursuits in

Italy beyond the mile radius and in the provinces" adding that "the benefit of the new law

rested as will be seen almost entirely with the travelling capitalists."

In my view, Heitland was half right. The law by passed by Porcius Laeca plainly

did concern provocatio - as evidenced by both the famous "Provoco" coin (Crawford

RRC 301/1) and Cicero's dramatic exclamation "O Lex Porcia!" in his attack on Verres.

(Cic. Verr. 2.5.163.) However, Heitland's suppositions regarding the purpose and

beneficiaries of the law have merit. The early second century saw dramatic expansion of

Roman military (and thus magisterial) activity outside of Italy - particularly in the Greek

east, an area of great commercial interest to Roman merchants. This would almost

certainly have led to increased contacts - and potential conflicts - between Roman

civilians and magistrates in the field. Whereas in earlier times, a Roman citizen

Copyright © 2014 by Arthur J. Wylene

interacting with a magistrate outside of Italy would likely have been a soldier, now he

might be an equite on business in (or adjacent to) an eastern war zone. The demand for

some form of legal protection for such civilians (i.e., wealthy men of substance) is a

logical reaction to these developments. Under this analysis, provocatio militae need not -

and would not - have extended to soldiers, thereby avoiding many evidentiary and

conceptual difficulties on that point. A Lex Porcia extending provocatio to civilian

citizens overseas would thus fit both the available evidence and the historical context.

It may further be worth considering the suggestion of Greenidge and J. S. Reid

(On Some Questions of Roman Public Law, JRS, 1911) that provocatio was extended first

to Italy - whether by custom or law - and only later to citizens overseas, which would fit

the historical development hypothesized above, and the different juridic treatment

accorded to Italy in related contexts. However, that is beyond the scope of this post.

Copyright © 2014 by Arthur J. Wylene

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Greek and Roman Sculpture in America (Art Ebook)Document448 pagesGreek and Roman Sculpture in America (Art Ebook)George Bakalas100% (3)

- Neer, Athenian Treasury at DelphiDocument36 pagesNeer, Athenian Treasury at DelphiKaterinaLogotheti100% (1)

- Antiquity Index, Lists and Tables Brill's New Pauly - Encyclopaed PDFDocument612 pagesAntiquity Index, Lists and Tables Brill's New Pauly - Encyclopaed PDFHellas SPQRNo ratings yet

- The Panegyricus of IsocratesDocument196 pagesThe Panegyricus of Isocratesthersitesslaughter-1No ratings yet

- Koine Greek: 2 Origins and HistoryDocument7 pagesKoine Greek: 2 Origins and Historynico-rod1No ratings yet

- Anthony Blunt - Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1700Document214 pagesAnthony Blunt - Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1700Karmen StančuNo ratings yet

- Pella Curse TabletDocument3 pagesPella Curse TabletAlbanBakaNo ratings yet

- HUM 2220 Rome Engineering An Empire Notetaking GuideDocument4 pagesHUM 2220 Rome Engineering An Empire Notetaking GuideDelmarie RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Illyria and IllyriansDocument3 pagesIllyria and IllyriansAdrian RepustićNo ratings yet

- GOLDSWORTHY, A. (2003) - The Complete Roman ArmyDocument226 pagesGOLDSWORTHY, A. (2003) - The Complete Roman ArmyNikolina33% (6)

- Varrones Murenae Ver3 - 2 PDFDocument33 pagesVarrones Murenae Ver3 - 2 PDFJosé Luis Fernández BlancoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Ancient History Volume 05 The Fifth Century BCDocument582 pagesCambridge Ancient History Volume 05 The Fifth Century BCBarbara Nazor100% (3)

- Marcus Junius BrutusDocument5 pagesMarcus Junius Brutusjoshualarco21No ratings yet

- Creators Conquerors and Citizens A History of Ancient Greece Robin Waterfield Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesCreators Conquerors and Citizens A History of Ancient Greece Robin Waterfield Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFanita.burlingame501100% (9)

- Athens-Attica LOWRES NewDocument69 pagesAthens-Attica LOWRES Newspidi3103No ratings yet

- Essential Question: - What Were The Lasting Characteristics of The Roman Republic & The Roman Empire?Document20 pagesEssential Question: - What Were The Lasting Characteristics of The Roman Republic & The Roman Empire?Canc3 LoliNo ratings yet

- The Roman CivilizationDocument10 pagesThe Roman CivilizationKyra Dabon JamitoNo ratings yet

- The Veterans and The Romanization of SpainDocument12 pagesThe Veterans and The Romanization of SpainlosplanetasNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political Motives: Factors That Motivated European Kingdoms To Explore The WorldDocument7 pagesEconomic and Political Motives: Factors That Motivated European Kingdoms To Explore The WorldHaru HaruNo ratings yet

- Homoioi. A. Andrews in "The Government of Classical Sparta" Goes Beyond A SimpleDocument6 pagesHomoioi. A. Andrews in "The Government of Classical Sparta" Goes Beyond A SimpleGiantPizzaFishNo ratings yet

- ONUS Army Ejercitos enDocument1 pageONUS Army Ejercitos encothysoNo ratings yet

- Basileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedDocument2 pagesBasileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedAnnabelle ArtiagaNo ratings yet

- Ancient History and The Antiquarian - Arnaldo MomiglianoDocument32 pagesAncient History and The Antiquarian - Arnaldo MomiglianoIgor Fernandes de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Domination of Philip IIDocument3 pagesDomination of Philip IIRéka RadványiNo ratings yet

- CICERON Comentario Pro RoscioDocument200 pagesCICERON Comentario Pro Roscioperulo1No ratings yet

- A Brief History of RomeDocument3 pagesA Brief History of RomeClaireAngelaNo ratings yet

- Caesar To The Empire Study GuideDocument19 pagesCaesar To The Empire Study Guideapi-320899644No ratings yet

- A Study of The Keles Event in Ancient Greece. From The Pre-Classical Period To The 1st Century B.C PDFDocument261 pagesA Study of The Keles Event in Ancient Greece. From The Pre-Classical Period To The 1st Century B.C PDFAlmasyNo ratings yet

- Democracy in AthensDocument2 pagesDemocracy in AthensSára UhercsákNo ratings yet

- Western Civilization Volume I To 1715 9th Edition Spielvogel Test BankDocument22 pagesWestern Civilization Volume I To 1715 9th Edition Spielvogel Test Banktimothyamandajxu100% (23)