Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Encase: A Case Study in Computer-Forensic Technology: Lee Garber

Uploaded by

Media Penelitian Dan Pengembangan Kesehatan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

105 views1 pageArtikel majalah komputer

Original Title

computer magazine article

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentArtikel majalah komputer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

105 views1 pageEncase: A Case Study in Computer-Forensic Technology: Lee Garber

Uploaded by

Media Penelitian Dan Pengembangan KesehatanArtikel majalah komputer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

IEEE

C O MP U TER Computer Magazine Technology News January 2001

SO C IE T Y

EnCase: A Case Study in Computer-Forensic Technology

Lee Garber

If you talk to many of the police de- in which deleted files and other poten- still not something the layman can pick

partments in the US with computer- tial evidence can be stored, said Shel- up right away. Even an IT person needs

forensics units, they’ll tell you that the don. Users generally could not view a good week of training on the soft-

tool they use most often is EnCase. such areas of the drive via the operating ware.”

In fact, about 2,000 law-enforcement system alone. Some criminals apparently are also

agencies around the world use it, ac- In displaying files, EnCase can sort aware of EnCase. Detective Christopher

cording to Jennifer Higdon, spokesper- them based on various criteria, such as Hapsas of the Los Angeles County

son for Guidance Software, manufac- extension or time stamp. In addition, Sheriff’s Department’s High-Tech

turer of EnCase. EnCase compares known file signatures Crimes Detail said there is a utility

EnCase, a 1-Mbyte program written with file extensions so investigators can called Evidence Eliminator that zeroes

in C++, offers an integrated set of foren- determine whether the user has tried to out a hard drive, rendering EnCase use-

sic utilities. Up to 15 tools were re- hide evidence from detection by chang- less.

quired to provide the same functionality ing its extension. Guidance also offers Nonetheless, said William D. Taylor,

in the past, which made the investiga- an EScript macro language that lets ad- president and CEO of the International

tive process time-consuming, expensive, vanced users build EnCase tools to pro- Association of Computer Investigative

and sometimes incomplete, said com- vide customized functionality. Specialists, “It’s a great program. I use

pany president and general counsel John Although EnCase automates the ex- it every day. It does the work for you, if

M. Patzakis. amination process, Patzakis said, “It is you know what you’re doing.”

With EnCase, investigators start by

placing a suspect’s hard drive in their

forensic computer. The drive can be

from a Windows, Macintosh, Linux, or

DOS machine. EnCase then makes a

bit-stream mirror image of the drive.

The mirror image is mounted as a

read-only evidence file. This prevents

investigators from altering the data and

thereby invalidating it as evidence, said

Bob Sheldon, Guidance’s vice president

and director of training. To verify that

mirror-image data is the same as the

original, EnCase calculates cyclical re-

dundancy checksums and MD5 hashes.

EnCase subsequently reconstructs

the drive’s file structure using logical

data in the mirror image. The investiga-

tor can then examine the drive via a

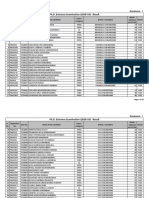

Windows GUI, as shown in the figure.

The Windows interface lets investiga-

tors use multiple tools to multitask,

something that past forensic tools’ DOS

interfaces didn’t permit, Sheldon noted.

In examining a drive, EnCase goes

EnCase lets investigators examine digital evidence files via a Windows interface. EnCase

beneath the operating system to view all

also can combine related evidence files from different drives into one case file. On the left is

of the data—including file slack, unallo- a case file’s directory structure, at the top right is the list of evidence files in the directory

cated space, and Windows swap files— the user has accessed, and at bottom right is the selected file.

Copyright © 2001 IEEE. Reprinted with permission from IEEE Computer Society’s Computer Magazine. Originally appeared as side-

bar to “Computer Forensics: High-Tech Law Enforcement,” in the January 2001 issue.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Lecture0 INT217Document25 pagesLecture0 INT217Shubham BandhovarNo ratings yet

- Computer-3 1st QuarterDocument5 pagesComputer-3 1st QuarterEdmar John SajoNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Digital Marketing Term PaperDocument4 pagesTerm Paper Digital Marketing Term PaperJonathan Jezreel InocencioNo ratings yet

- Result - Final (Annexure - I) - 923680Document25 pagesResult - Final (Annexure - I) - 923680patelsandip1989No ratings yet

- KerosDocument9 pagesKerosMarius Mihail BențaNo ratings yet

- 崇正华小下午班放学指南 - 致家长 -, 1 Mac 2021Document37 pages崇正华小下午班放学指南 - 致家长 -, 1 Mac 2021yanNo ratings yet

- Use of Mobius: THE Transformations IN Neural Networks and Signal Process1 N GDocument10 pagesUse of Mobius: THE Transformations IN Neural Networks and Signal Process1 N GNavneet KumarNo ratings yet

- Omarlift Brochure - HM Pump UnitDocument1 pageOmarlift Brochure - HM Pump UnitKhaled ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Maximum Supported Hopping Rate Measurements Using The Universal Software Radio Peripheral Software Defined RadioDocument7 pagesMaximum Supported Hopping Rate Measurements Using The Universal Software Radio Peripheral Software Defined RadioM FarhanNo ratings yet

- Adhesive Bandage: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument6 pagesAdhesive Bandage: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchtokagheruNo ratings yet

- DsersDocument15 pagesDsersT JNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Online Submission of ApplicationsDocument15 pagesGuidelines For Online Submission of ApplicationsMuhammad Asif Mumtaz FaridiNo ratings yet

- IsfileexistsDocument25 pagesIsfileexistsRAMESHNo ratings yet

- Hungarian Algorithm For Solving The Assignment ProblemDocument10 pagesHungarian Algorithm For Solving The Assignment ProblemRavi GohelNo ratings yet

- Manual IFQ Monitor en Rev 08-2022Document50 pagesManual IFQ Monitor en Rev 08-2022Gerald StiflerNo ratings yet

- READ ME - InfoDocument2 pagesREAD ME - InfoSalih AktaşNo ratings yet

- Gmaw and Metal TransferDocument14 pagesGmaw and Metal TransferAnant AjithkumarNo ratings yet

- Tabla Dim Tuberia R410aDocument1 pageTabla Dim Tuberia R410aFernandoNo ratings yet

- Tec 516 Topic 2 Legal and Ethical Questions Scavenger HuntDocument8 pagesTec 516 Topic 2 Legal and Ethical Questions Scavenger Huntapi-623433089No ratings yet

- Introduction To Library Metrics: Statistics, Evaluation and AssessmentDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Library Metrics: Statistics, Evaluation and Assessmentgopalshyambabu767No ratings yet

- 117JJ112016Document2 pages117JJ112016DEVULAL BNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Robotics Matlab CodeDocument7 pagesPHD Thesis On Robotics Matlab Codeprdezlief100% (2)

- Conference Report TemplateDocument4 pagesConference Report TemplateAALUMGIR SHAH100% (2)

- Amira: AMIRA Camera Sets Mechanical AccessoriesDocument1 pageAmira: AMIRA Camera Sets Mechanical AccessoriesJonathanNo ratings yet

- Technology and Society Unit 3Document21 pagesTechnology and Society Unit 3me niksyNo ratings yet

- Penetration Testing (White)Document1 pagePenetration Testing (White)alex mendozaNo ratings yet

- Nsec Btech Brochure 2022 ReDocument71 pagesNsec Btech Brochure 2022 ReFood RestorersNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Resume Action Words TipsDocument3 pages2.2 Resume Action Words TipsMichelle SavanneNo ratings yet

- Oxford Solutions Intermediate Cumulative Test Answer Keys ADocument5 pagesOxford Solutions Intermediate Cumulative Test Answer Keys AAleks50% (2)

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To System AdministrationDocument27 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction To System AdministrationAbdul KilaaNo ratings yet