Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BH Ojo Ramos Zincke (2014) Local and Global Communication

Uploaded by

bherrera1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BH Ojo Ramos Zincke (2014) Local and Global Communication

Uploaded by

bherrera1Copyright:

Available Formats

Current Sociology http://csi.sagepub.

com/

Local and global communications in Chilean social science: Inequality and

relative autonomy

Claudio Ramos Zincke

Current Sociology 2014 62: 704 originally published online 24 February 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0011392114521374

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://csi.sagepub.com/content/62/5/704

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International Sociological Association

Additional services and information for Current Sociology can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://csi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://csi.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Aug 27, 2014

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Feb 24, 2014

What is This?

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

521374

research-article2014

CSI0010.1177/0011392114521374Current SociologyRamos Zincke

Article CS

Current Sociology

Local and global

2014, Vol. 62(5) 704–722

© The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

communications in Chilean sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0011392114521374

social science: Inequality and csi.sagepub.com

relative autonomy

Claudio Ramos Zincke

Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Chile

Abstract

This article analyzes the connections of the social sciences in Chile with the knowledge

produced in central countries in comparison to those established within Chile and

with other Latin American countries, paying particular attention to the connections

regarding theory. It is based on content analysis of academic publications, and on social

network analysis applied to a database of more than 20,000 bibliographical references

generated for this research project from the universe of investigations published by

Chilean social scientists over a period of seven years in the first decade of this century,

in journals and books, both in Chile and abroad. The results show that, regarding

international communications, there is a low level of connectivity with other Latin

American countries, but that the communications among Chilean authors are relatively

important and particularly those with a group of local theorists who occupy central

positions in the network. This does not appear to be a pattern of cognitive dependence

although it occurs within the context of a global science that is characterized by a

remarkable inequality.

Keywords

Citation, cognitive dependence, scientific communication, scientific regulation, social

network, social science

Corresponding author:

Claudio Ramos Zincke, Department of Sociology, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Cienfuegos 46, Santiago,

Chile.

Email: cramos@uc.cl

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 705

The objective of this article is to analyze the connections of the social sciences in Chile,

a Latin American semi-peripheral country, with the knowledge produced in central coun-

tries in comparison with those established within Chile and with other Latin American

countries, paying particular attention to the connections regarding theory. This is dis-

cussed in the horizon of concerns for scientific regulatory and evaluative mechanisms

and their effects on peripheral or semi-peripheral countries like Chile. Such mechanisms

create a notable separation between central science and marginal science. According to

some authors, together with this separation is established a relationship of intellectual or

cognitive dependency, or a colonialism of knowledge (Connell, 2007; Lander, 2004;

Mignolo, 2003, 2004). However, when the whole of the body of knowledge produced in

the social sciences and the communications established by the scientists of these periph-

eral or semi-peripheral countries are examined – and not merely the sub-set selected by

the devices of the core countries is studied – the situation is more blurred and the depend-

ency relationship becomes much less evident; there is a play of local and global relation-

ships that is much more complex, wherein dependency and autonomy superimpose

themselves. From such perspective, this article seeks to provide some empirical elements

for the discussion of the thesis of cognitive dependence based on the study of the particu-

lar case of Chile.

With that objective, in the following sections: (1) I review the stratified construction

of the social sciences at the international level and the devices that shape it, including the

role of local scientific institutionality and I pay attention to the interpretation made of

this as a situation of cognitive dependence; (2) I describe the methodology used for the

empirical research; (3) I analyze the distribution pattern of local and international com-

munications of the social sciences in Chile, (4) giving special consideration to the con-

nections with theorists; and (5) I arrive at conclusions regarding local and global scientific

communications and the possible condition of cognitive dependence.

Building ‘central science’, the mechanisms for its

production and its effects in Latin America

Science, in all its areas, has had a transnational orientation since its beginnings with

modernity, gathering knowledge from diverse parts of the world and it has claimed the

universality of the knowledge generated – although in practice there has been a clear

predominance of the knowledge originating in the central countries, without a proper

validation in other places of the world. This predominance is strengthened by the pecu-

liar characteristics of the devices employed in recent decades to select and to regulate

scientific production.

Together with the advances made in defining methodological procedures for evaluat-

ing and proving its hypothetical statements, science has had to design institutional mech-

anisms for communicating, evaluating and selecting scientific communications. The first

printed bibliography –a register of about 10,000 books– was made in 1545, and putting

it together took years of work (Burke, 2002). The publication in journals of the results of

scientific undertakings began in 1665. The scientific societies and academies that arose

during the 17th century were crucial for the invention of the scientific journal, the use of

which began to expand as a communication medium in replacement of the letters,

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

706 Current Sociology 62(5)

treatises and books which were the common way of communication until then. The first

two journals appeared in 1665, one in England – the famous Philosophical Transactions

– and another in France (Merton, 1973). The generalized practice of using footnotes

comes from the 17th century (Burke, 2002) and only in the 19th century did the format

of scientific papers become more or less established and generally adopted, including the

peer review system and the standardization and general usage of the academic apparatus

of notes and quotes (Merton, 1973). Scientific societies, congresses, academic journals,

the peer review system and bibliographic references are some of the procedures taken for

granted today but that have only gradually been refined and stabilized over four

centuries.

Following the Second World War, at a time of tremendous growth in scientific activ-

ity, a last great device appeared that would have powerful effects on the structure of

global science in the decades to come: the bibliometric register of articles and authors,

and of the quotes that refer to them in a body of journals selected as being the best

known. It is a device supported by the mechanisms already operative in a scientific jour-

nal, particularly the bibliographical references and the peer review procedure, and by a

prestige structure that had taken form and was recognized in some fields of science.

There were several other trials attempted previously, but the Scientific Citation Index

(SCI), developed by Eugene Garfield in the US, finally imposed itself around 1961. It

was based on an automated procedure that does away with human classification, and was

managed by a private institution with commercial aims, the Institute for Scientific

Information (ISI). Originally concentrating on the biomedical field, it rapidly expanded

to involve other disciplines, and in 1972 the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI)

appeared. Garfield’s institute would be bought in 1992 by Thomson Business Information

(now Thomson Reuters), another private and multinational corporation, based in Canada

and the US, that strengthened the services provided by the index and moved its operation

onto the Internet, multiplying its earnings (De Bellis, 2009). These indexes became the

main tools for regulating science around the world, being the main ways to manage the

relevance of the articles and the levels of prestige of scientists, enjoying an undisputed

preeminence through the end of the 20th century. They are an answer to the enormous

proliferation of publications, which would become unmanageable both for the scientific

community and other users of scientific information if they could not rely on these filter-

ing and ranking mechanisms of published literature.

When these indexes were put together, there was no great effort made to achieve

within them a representation of the various regions of the world. Selection was made

with a view towards the central countries, and particularly from an Anglo-Saxon point

of view. This is reflected in the predominance of the English language: between 1998

and 2007, 94.5% of the articles in the SSCI were written English, and only 0.4% in

Spanish, for example (Gingras and Mosbah-Natanson, 2011). This involves the benefit

of having a lingua franca for science but it has an asymmetrical cost for access (Ammon,

2011). As regards regional representativeness, during the 1970s there was next to no

presence of Latin America or Asia. There was only one journal from Chile among all of

the scientific disciplines. In later years there has been an effort to increase the diversity

of origins, but despite all of that, there is still a great concentration. In 2010, the US and

Europe were the source of 84.3% of all of the journals included in the SCCI, with 49.5%

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 707

from the US, 23.7% from the United Kingdom and fewer than 3% from Latin America

(Rodríguez, 2010).

In 2004, the Elsevier publishing company based in Europe (Amsterdam) launched a

new database and citations index, Scopus, which broke the monopoly of the North

American Thomson Scientific.1 At the same time, other more open search engines like

Google Scholar gained relevance. This caused an overall increase of the number of pub-

lications included in these indexes, although Scopus, with its commercial outlook, the

greatest change that produced was the increase in the proportion of European publica-

tions (Guédon, 2011).

These indexes and citation databases that mix the selectivity characteristic of pre-

existent scientific recognition with the selectivity criteria that arise from the geopolitical

and sociocultural positions of those who construct the index, provide orientation for the

searching and reading of scientists and for the making of institutional decisions, particu-

larly those of librarians in purchasing scientific publications (Vessuri, 2008). They gen-

erate a collective ‘Matthew effect’, not only referring to the most visible authors who are

recognized as prestigious, as described by Merton (1973), but also referring to visible

journals recognized as prestigious. As a result of their selection in the index they concen-

trate the preferences for publication and reading, to the detriment of others that are not

included. This produces a massive ratification of the privileged status of these journals.

The initial qualification of the journals is self-validated. Those that are included, and

thereby made visible, are more frequently cited, and those that are excluded and there-

fore less visible do not attract submissions for publication or citations, at least not as a

consequence of the effect propagated worldwide that the index produces. Even more, the

exclusion extends to entire regional clusters of journals and the sub-representation

becomes consolidated, resulting in a configuration of a global science that is markedly

associated with the central countries, particularly the Anglo-Saxon countries, as a per-

formative effect of the mechanisms registering publications and citations. SSCI and

Scopus shape this central science; the very make-up of the devices and the way they

operate cause this shaping to stabilize and reproduce itself.

Since the 1990s, as a reaction against this scientific marginalization, several indexes

and journal databases have been created in Latin America: Redalyc, Latindex and Scielo.

They try to articulate and increase the visibility of the regional production in the social

sciences. Scielo, also including Spain and Portugal, promoted by the Brazilian govern-

ment, is the index that has achieved the greatest recognition from the academic world. In

second place is Latindex, which operates from Mexico and is chosen above all for its

most demanding version: Latindex Catálogo (Guédon, 2011; Rodríguez, 2010).

The scientific institutions in Chile, in the area of the social sciences, have assigned

full validity to the central indexes, especially to the SSCI, commonly referred to as ISI,

and to Scopus, assuming them as objective and unquestionable standards of quality.

Scielo is recognized as belonging to a secondary category and Latindex to a third rank

category. The National Council for Science and Technology (Conicyt), which is the pri-

mary source of government support for research in the social sciences, currently defines

that a requirement for the approval of a research project proposal is the achievement of

at least one ISI publication. In 2007 Conicyt imposed this condition, whereas before it

had only been a recommendation.2 Furthermore, within the competition among social

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Este es el caso de la

revista ‘Estudios

708 según

Públicos’, Current Sociology 62(5)

encuesta aplicada a 37

investigadores

science research projects, operated by Conicyt, researchers receives almost three times

destacados del mundo

as manynacional,

académico qualifying fuepoints for an ISI or a Scopus publication than for a Scielo publica-

tion, points

considerado como lathat are often decisive factors in the overall approval decision. And it is

worthwhile

revista pointing

más valorada. A out that Chile has a very limited number of ISI journals: none in

sociology,

pesar one in en

de este hecho, political science and two in anthropology, which undoubtedly puts

la competencia

pressure on por la to publish abroad. On the other hand, some of the better recognized

people

financiación de

and most

proyectos read journals in Chile are neither ISI nor Scielo indexed. This is the case of

la calificación

Estudios Públicos,

en puntos apenas which in a survey that I applied among 37 outstanding researchers of

the national

recibe un tercio o academic world, was considered to be the most highly valued journal. In

spiteque

menos of this

una fact, in the competition for project funding, it receives a third or fewer points

revista

publicada

than a en revistas in an ISI or Scopus journal.

publication

indexadas en ISI o de

Scopus. Something similar occurs with the evaluations made in the country of the institutional

productivity at universities or other scientific centers.3 The most frequently used indica-

tor for ranking and making comparisons is the number of ISI publications. As a conse-

quence, an increasing number of universities, particularly new private universities,

founded since the 1980s, are now offering economic incentives for achieving that type of

publications, with amounts of money that, in some cases, are close to a month’s salary,

being extremely attractive, given the tight economic situation of scholars in Chile. Some

universities include this kind of incentive for Scielo publications, repeating the stratified

pattern, by offering sums that are between half and one-third of those offered for ISI

articles. Furthermore, these publications, especially those in ISI, are considered to be a

privileged indicator of individual productivity and so they influence professional

advancement. In that way, Chilean scientific institutions themselves, wherein the very

researchers

¿Puede participate,

concluirse ((de promote the reproduction of this stratified structure of a central

lo observado: 91% de highly valued, and a peripheral science.

social science, more

What, then,

los artículos are the

chilenos seeffects of this structuring of global science, and the way of embed-

ding Chilean

registran socialde

en revistas sciences in it? It is clearly a type of communication that has been

Europa y USA))

established on aque

foundation of inequality, for which the rules for the selection of journals

existe una dependencia

are set by scientific regulatory corporations located in the central countries and the selec-

cognitiva o intelectual?

tionesta

¿Es of articles is defined by evaluators who are principally from those same countries.

una cuestión

Local social

de colonialidad delscience competes at a disadvantage, and nor do its local academic institu-

tions stimulate,

saber? En las últimas as we have seen, publication in local journals, no matter how well quali-

décadas

fied theysurge

are. un

pensamiento crítico

When we look at scientific communications from the point of view of the databases

cuyo hilo conductor es

and indexes

la dependencia of centralized science, the following results emerge (see Table 1). Scientific

production in Latin America barely exists for the central countries: Europe and the US

cognitiva o epistémica

make fewer

(Mignolo, 2004),than 1% of their citations to authors from that region. For its part, Latin

el tipo

de conocimiento

America orientates 90.1% of its references to those countries, a situation that is repeated

colonial (Lander, 2004)

in Asia and Oceania. This is to say, if we make an evaluation on the basis of the exchange,

y, en general, en cuanto

althen we have

problema de alas

total imbalance.

Can it be

relaciones centro /concluded from this that there is a cognitive or intellectual dependence? Is

this a matter

periférico en la of coloniality of knowledge? Over the past decades, a thread of critical

generación

thought hasdel appeared regarding epistemic or cognitive dependency (Mignolo, 2004), the

conocimiento (Alatas,

colonial nature of knowledge (Lander, 2004) and, in general, about the problem of the

2003; Burawoy et al,

relationships

2010;. Connell,between

2007; the central and the peripheral countries as regards the generation

Mignolo, 2003, 2004;

UNESCO, 2011).

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 709

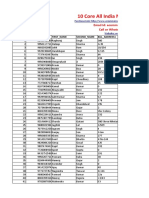

Table 1. The orientation of the social science citations worldwide, 2003–2005 (in the 200

most cited journals, in percentages).

Country or region making the reference

USA Europe Latin America

Country USA 78.1 47.9 56.2

or region Europe 20.4 50.3 33.9

referred to Latin America 0.2 0 6.9

Rest of the world 1.3 1.8 3.0

100.0 100.0 100.0

Desde estos puntos

Source: de

SSCI, Gingras and Mosbah-Natanson (2011).

vista, el problema es el

uso excesivo e

of knowledge

inapropiados de (Alatas, 2003; Burawoy et al., 2010; Connell, 2007; Mignolo, 2003, 2004;

categorías UNESCO,

y del juicio2011). From this point of view, the problem is the excessive and inappropriate

teórico y use

conceptual

of theoretical and conceptual categories generated in the central countries, without

generados desde los

países centrales,the

giving sinnecessary

el attention to their coincidence with local realities in the peripheral

countries,

necesario cuidado en and without a local production able to generate its own stream of knowledge,

que taleswhich

juicioscould

o develop a cognitive relation, on an equal standing, with the core countries,

categorías and, furthermore, which could overcome the marginality of autochthonous currents of

coincidan

con las realidades

thought.

locales de los países

Although science supports itself upon a global accumulation of knowledge and has an

periféricos, impidiendo

inherent

generar sus propios pretension of universality, in the social sciences, local references are extremely

important,

flujos locales de in a way that is not present in other scientific disciplines. In this regard, all the

social de

conocimientos; science disciplines involve important and meaningful configurations of knowl-

lograse superar esos

edge associated to local areas (e.g., sociological knowledge about France, political sci-

problemas se podría

desarrollar una relación of certain realities of the United States, and so on). Even in the field of

ence knowledge

cognitiva economics,

de confianza, which certainly has a self-image of being global, some of its theoretical

dando pieconstructs

a igualdadand de statements contain marked national differences, as shown with conspicu-

condicionesousfrente

precision

a losin the study made by Fourcade (2009) that compares the USA, the UK and

países centrales,

France; they, por

flags of the universal nature of knowledge, so ardently waved by economists,

otra parte, generando

cause those

las posibilidades para

differences to pass unnoticed. Such cognitive differences are associated with

the peculiar

superar la marginalidad characteristics of the institutions that deal with the production and transmis-

sion of knowledge, and with their ways of entanglement with the rest of society.

de las corrientes

autóctonas de To analyze the situation of cognitive dependence in a particular country, like Chile,

pensamiento.

my assertion is that it is not adequate to judge the direction of scientific communications

and to ponder the possible cognitive dependence with regard to the central countries by

limiting our observation to what happens in the central indexes and citation databases. It

needs to be taken into account that this Latin American social science, which makes

fewer than 10% of its references to Latin American countries (Gingras and Mosbah-

Natanson, 2011), represents but a small fraction of the social science production in this

region, and that the authors of this group, selected by central indexes, are precisely those

involved in establishing a dialogue with the production of the central countries. So it is

necessary that we analyze what is going on with the rest of the national production.

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

ESO ES LO QUE SE

PRETENDE HACER

710 Current Sociology

EN ESTE 62(5)

ARTÍCULO,

EN EL CASO

CHILENO. ELEGÍ ESTE

That is what I shall do here with regard to Chile. I choose this countryPAÍS to examine

PARA EXAMINAR

ideas about cognitive dependence. In global economic and power relations, IDEASChile,SOBRE LA

although subordinate to core countries, has an intermediate position and has DEPENDENCIA

been consid-

ered a semi-peripheral country (Babones and Alvarez-Rivadulla, 2007). ItCOGNITIVA.

can be sug- EN LA

ECONOMÍA Y EL

gested that the results found regarding Chile could be hypothetically extended SISTEMA to other

DE

semi-peripheral countries, at least from the region, such as Brazil, Mexico and Uruguay.

RELACIONES

I will analyze, then, what direction scientific communications take whenGLOBALES

we base ourDE

analysis on the universe of social scientific production being generated in PODER,

the country,

and how strong the orientation is towards the central countries as opposed toCHILE -AUNQUE PAÍS

the orienta-

SUBORDINADO A LOS

tion towards Chile itself and the Latin American region. PAÍSES CENTRALES-

As part of this analysis and by paying attention to the assertions about TIENE cognitive

UNA POSICIÓN

dependence, I also question what is happening regarding theory. Theory isINTERMEDIAat the very Y HA

center of the making of scientific observation and of the way reality is interpreted and

SIDO CONSIDERADO

explained. So I seek to identify the sources of theory used in the country – inCOMO

terms of UN thePAÍS

SEMI-PERIFÉRICO

theorists referred to by national researchers and with whom they establish a(Babones

dialogue in y Alvarez-

their publications – and who are the most central theorists in the field. At theRivadulla,

same time, 2007). A

I ask if there are local theorists who are relevant within the network of theoretical

PARTIRcon- DE LOS

nections. Once that has been analyzed, the question is what the findings RESULTADOS,

have to say SE

about the eventuality of cognitive dependence. PODRÍA DECLARAR A

CHILE

HIPOTÉTICAMENTE

Methodology COMO EQUIPARABLE

A OTROS PAÍSES

For this analysis of the scientific communications as observed from the Chilean field

SEMIPERIFÉRICOS,

itself, I have taken three basic disciplines of the social sciences: sociology,POR LO MENOS

which has DE

LA ZONA, COMO

achieved notable progress in becoming established institutionally in this country during

BRASIL, MÉXICO Y

the 1960s; political science, at first with strong links with and dependence URUGUAY

upon sociol-

ogy but gradually consolidating its own institutionality since the 1980s; and anthropol-

ogy, which made early progress in the country, at the beginning of the 20th century,

although its institutionalization and development have been slower (Fuentes and Santana,

2005; Garretón, 2005; Palestini et al., 2010; Ramos, 2005; Ramos and Canales, 2009;

Rehren, 2005). Economics was not included because for Chilean scientists, at least in the

period studied, it is conceived as a separated field, whereas sociology, political science

and anthropology are viewed as part of the same field. This is similar in the social sci-

ences of other Latin American countries (Trindade, 2007). The discipline of economics,

with all the complexities involved, would require its own research.

Research into scientific communications has habitually considered only articles pub-

lished in journals, because of their accessibility. This is valid in sciences like chemistry

or biology, where most of the results of research effectively appear in journal articles, but

Con el finin de

theevitar

sociallasciences, the pattern of publications is different. In particular, sociology has

distorsiónbeen a culture

((cuando el of the book, as indicated by Clemens et al. (1995) writing about the US,

análisis and

se limita

thereaare estimates that suggest that ‘between 40% and 60% of the literature of the

artículos)), se incluyen

todos lossocial sciences is comprised of books’ (Archambault and Larivière, 2011: 264). So, in

formatos

order to avoid distortion, I have included all the formats that are relevant to social scien-

relevantes a la difusión

social del conocimiento dissemination in the country: books, book chapters, journal articles and

tific knowledge

científicopublicly available working papers.

en el país:

libros, capítulos de

libros, artículos de

revistas y de

documentos de trabajo Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

(‘working-papers’)

disponibles anualmente.

Ramos Zincke 711

I concentrated attention on publications that make up the core of scientific activity:

publications that report research results, which is to say those that involve the generation of

new knowledge through systematic research, empirical or theoretical. Therefore, I have

excluded book reviews and opinion pieces, and texts that do not meet the minimal require-

ments for selection in a social science journal of recognized quality. To select a text, its

author – or at least one of the authors, in the cases of multiple authors – should have under-

graduate or graduate education in one of the three aforementioned disciplines. I included

not only researchers who were Chilean citizens, but also those who were residents in Chile

during the period of study and who were active participants in their disciplines.

The research tried to cover the universe of texts that fulfilled the requirements men-

tioned and that were published between 2000 and 2006. The research team gave special

attention to gathering material produced outside of the central metropolitan region, and

we traveled to regional centers looking for texts. We also reviewed a variety of series of

working papers and institutional publications, both private and public, and from interna-

tional organizations located in Chile, and we requested texts from those researchers who

Usando lamight

lógicahave

de copies of those that we were unable to locate. Regarding publications made

in foreign

análisis de co-citación journals, we reviewed ISI and Scielo social science journals, and looked for

Chilean

consideramos queauthors

una who wrote in them. All of this was a demanding effort made to achieve

conexión aentre dos coverage, so that those texts that were finally not identified nor found would

maximum

autores en temas

teóricos, produce represent a very small fraction of the whole body of work, and there are no rea-

have to

sons for

cuando ambos sonthinking that there was any bias involved in their being excluded; their distribu-

tion must

co-citados en el corpus be random. The final corpus comprised 479 texts.

With2003).

del texto (Gmür, two other researchers, we read each text, reviewed it and made its characteriza-

tion based on a variety of features, one of which, pertinent to this article, was the intended

destination of knowledge. We determined the principal destination for the knowledge

generated considering what was said explicitly in the texts themselves and through infer-

ences based on available data.

Furthermore, we recorded all the bibliographical references contained in each text.

After long and very time-consuming work, we obtained a total of 21,787 bibliographic

references, and we specified all of the characteristics of each one.

Among the references we distinguished those that cite theorists, understood as authors

whose work reaches sufficient levels of abstraction and generalization articulating a

hypothetical argumentation with sufficient coherence, consistency and originality. To

study the connections with theorists and the networks that involve them we applied

social network analysis (Degenne and Forsé, 2004; Scott, 2000; Wasserman and Faust,

1994). Using the logic of co-citation analysis we considered that a connection between

two theoretical authors occurs when they are both cited in the same text of the corpus

(Gmür, 2003).4

Local and global dimensions of social science in Chile

Table 2 presents the distribution of the publications effectively found and studied,

according to discipline of the authors and format of the publication. These figures con-

firm the importance of books in Chile as media for transmitting knowledge in the social

sciences, especially in sociology. This reveals the degree of distortion that may result

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Del total de los textos

encontrados, sólo el

7,6% se publican en el

712 extranjero. Se podría Current Sociology 62(5)

suponer que, apoyado

en este pequeño grupo,

Table es2. sobre

Distribution

quienesof publications

se ha by format and discipline (in percentages).

ejercido el impacto de

Format TOTAL Disciplines

los países centrales

definiendo desde ese Sociology Political science Anthropology

7,6 % la agenda local

Journalde

article

investigación. Sólo 42.4 34.0 52.1 53.8

Book orunbook

grupo muy pequeño

chapter 35.9 45.2 23.6 25.5

Workingde paper

estosortextos

similar format 21.7 20.8 24.3 20.8

ubicados en la esfera

central de la ciencia, 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

ocupan un lugar (479) (268) (165) (106)

relevante en las citas

Note: In some cases, there have been multiple authors and a text was classified in more than one discipline,

nacionales de

so the total of the articles by discipline is greater than the sum of the articles.

publicaciones, mientras

que los otros se

from anlocalizaron

analysis of enpublications

una in the social sciences that does not take this format into

segunda línea de citas y

account. The book

reconocimiento. Por is a cognitive product with manifestly different characteristics and

with capabilities

otra parte, casithat an article has not, that are outstanding in the field of the social sci-

la mitad

ences.deIn los

order

mástofrecuentes

include descriptive stories and explanations of some complexity in

society, with an

autores integrative

citados en el aim, supported by an adequately developed line of argument

país no han publicado

and backed up by a store of empirical material, a journal article is insufficient. There are

afuera de Chile. Es

numerous works in the social sciences that have made considerable impact in Chile that

decir, EN LAS

have been published

CIENCIAS as books. I can mention: Chile: The Anatomy of a Myth, by Tomás

SOCIALES,

Moulian; Chilean Identity, by Jorge Larraín; The Paradoxes of Modernization, by the

EL PRESTIGIO

UNDP; Culture and Modernization

INTERNACIONAL NO in Latin America, by Pedro Morandé; and The

COINCIDE CON EL

Shadows of the Future, by Norbert Lechner. The impact achieved by such works would

PRESTIGIO

be unimaginable

NACIONAL. ALGO

in the format of a journal article. One cannot find journal articles of

comparable

PECULIAR,levels ENTRE

of impact. On the one hand, those formulations are not condensable

into the

LOStight space allowed for an article; and on the other, academic journals in Chile

MEJORES

are of INVESTIGADORES

a very restricted level of circulation within the academy and they are not generally

able toLOCALES QUE from outside academia.

attract a public

APARECEN EN EL

Of the total of the texts found, only 7.6% had been published abroad. One might sup-

CONCIERTO

pose that it is basically over

INTERNACIONAL EN this small group that the central countries would have exer-

cised an

SUinfluence

MAYORÍA in ESOS

defining their research agenda. Of these texts, located in the sphere

of central science, TIENEN

CHILENOS a few also occupied positions of relevance in national publications and

RELACIONES

citations, whereas theCON others were located in a second line of citations and recognition.

On theLASotherINSTITUCIONES

hand, nearly half of the most frequently cited authors in the country have

EN LOS PAÍSES

not been published abroad.

CENTRALES. Por lo That is to say, in the social sciences, international prestige

does not

quecoincide with national prestige. Something peculiar to those who are better

esa condición

playersfacilita

of themantener

international game is that most of them have relationships with institutions

in the contactos

central countries,

personales which

y facilitates their maintenance of personal contacts and a

una presencia física en

physical presence in those countries, and not merely a connection by way of their pub-

esos países, más allá

lished de

writing.

su conexión por

To medio

appraise dethe relative importance of local and global dimensions of Chilean social

artículos

science, the analysis of the distribution of bibliographic references provides us with a

publicados.

measure of the degree of attention that social scientists give to local production of

knowledge – either to the national or to Latin American production – in contrast with

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 713

the attention given to knowledge generated in the central countries; this allows us to

determine the direction textual communications take. Thus, we have classified the

21,787 identified references according to the cited author’s country. The categories

applied are: (1) Chile; (2) other Latin American country; (3) the USA (and Canada,

although there are few references to this country); (4) the UK (mainly England ); (5)

France; (6) Germany; (7) Spain; (8) other European country (Belgium, Italy, Poland,

Austria, Sweden, etc.); (9) other country (India, Japan, Israel, China, Australia,

Singapore, etc.); (10) several countries for the same reference or unidentifiable country.

The resulting distribution of the references is presented in Table 3, which also groups

them according to the discipline of the researcher making the citation.

Table 3. Distribution by country of the bibliographic references, according to the discipline of

the citing author (distribution of the cited authors, in percentages).

Country of origin of Discipline of the citing Chilean author TOTAL

author cited

Sociology Political science Anthropology

Chile 44.6 39.2 43.2 42.6

Other Latin American 10.7 10.2 12.7 10.8

country

USA/Canada 14.1 27.8 11.9 18.5

UK 4.6 6.0 5.3 5.2

France 5.6 2.7 7.0 4.8

Germany 6.3 4.0 4.2 5.3

Spain 5.6 4.5 7.4 5.5

Other European country 3.0 3.8 2.6 3.2

Other country 0.4 0.8 0.6 0.6

Several or unidentified 5.0 1.0 5.1 3.6

countries

TOTAL 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

(11,582) (7369) (2836) (21,787)

It can be observed that Chilean social science shows a clear local vector: 42.6% of the

references cite Chilean authors and allude to discussions about the country. There is a

clear orientation to the social problems that are of local concern: social inequality, pov-

erty, educational problems, the evaluation of public policy, social movements, gender,

etc. and the knowledge generated has a significant orientation towards local audiences.

If we consider the destination for which the work was intended, apart from the aca-

demic community itself, the other large destination for knowledge is the state. About

40% of all the production of the three disciplines studied has that destination, whether

because of demands coming from the state itself, or because they are the initiative of

other institutions – universities, non-governmental organizations or international

organizations – which seek to influence in the definition of policies, programs or other

governmental decisions. Sociology, particularly, demonstrates a strong connection

with the state apparatus: nearly half of its production is interconnected with the state

or oriented in its direction. Governmental organisms such as the National Institute for

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

714 Current Sociology 62(5)

Youth (INJUV) or the National Service for Women (SERNAM) are frequently demand-

ing social science research. On the other hand, 18% of the production is oriented

towards civil society entities (social movements, NGOs, political parties, etc.).

As we see in Table 3, the international or global direction is also very important in the

communications Chilean social scientists made. Particularly important are those com-

munications that have to do with the production of the central countries (42.5% of all the

references), the USA appearing as the main pole of attraction.

Comparing disciplines, political science appears as the most focused on the global

orientation: 48.8% of its references are made to central countries (vs. 39.2% from sociol-

ogy and 38.2% from social anthropology). In this discipline also noteworthy is the

greater relative importance assumed by the US. It is, moreover, the discipline in which

the members have a greater number of publications in foreign journals. Thus, political

science is the discipline that now appears to be the most internationalized.5

The regional dimension – references to knowledge generated within Latin America

– has a reduced presence: only 10.8%. The field of social science in Chile shows little

interest in Latin American production. We do not have comparative information for peri-

ods in the past for Chile, but I would think that the proportion of references made to Latin

America has been decreasing since 1970s, when there was much more attention to the

region. In fact, according to an analysis for the entire region, using the SSCI database,

the citations from Latin American authors to other Latin Americans have been declining

in number: in the period 1993–1995 they corresponded to 11.7% of total citations, while

between 2003 and 2005 this figure dropped to 6.9%, giving way to a greater proportion

of connections with the US and Europe (Gingras and Mosbah-Natanson, 2011).

Regarding the inequality between central science and regional science derived from the

operation of indexing and ranking systems, the variety of forms of pressure and institutional

incentives that place greater value on the central standards determined by ISI and Scopus

have been turning researchers towards the publications that are blessed by said indexes, and

that seems to be setting the future tendency. In the case of sociology, during the decade of

the 1990s the average of ISI publications was 1.5 articles per year (Farías, 2004); in the

period 2010–2012 the rate is 15.3 by year (Web of Science). The Scielo and Latindex

Catálogo publications have also increased in number but well below that rate of growth.

The strong institutional preference for prioritizing ISI publications can increasingly

tilt the balance towards global connections, especially Anglo-Saxon. In fact, in ISI arti-

cles the references to national authors are substantially lower, still much lower than those

in books, book chapters and articles with Scielo or Latindex indexing, or articles without

indexing.

This value given to the central standards, which leads scientists to seek publication at

the international level, especially in English, causing negative impacts on national jour-

nals and the publication of books, is constantly being criticized by scholars and local

authorities, but universities and scientific institutions apply those standards of evaluation

because they are broadly legitimized and have become part of the rules of the game.

The structure of communications with theorists

To investigate the connections with theorists, I began by reviewing the existence of

references to a list of 120 internationally recognized theorists, and found that, from the

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 715

total of 21,787 bibliographic references, 10% were referred to them: 11.4% in sociol-

ogy, 7.5% in political science and 10.5% in anthropology.6 There were 50 theorists who

got more than 10 references in the whole field, but in each discipline about 40% of

references were concentrated on five main authors (52.4% in anthropology, 39.9% in

sociology and 37.8% in political science). See Table 4, which presents the 25 most cited

authors in the field.

Table 4. Internationally renowned theorists most cited in the field (the top 25, in

percentages).

Author Country Discipline of the citing researcher TOTAL

Sociology Political Anthropology

science

1 Luhmann, Niklas Germany 11.9 (1) 0.5 13.2 (2) 9.4

2 Bourdieu, Pierre France 7.0 (3) 1.0 16.5 (1) 6.9

3 Giddens, Anthony England 7.1 (2) 2.7 7.4 (4) 6.1

4 Habermas, Jürgen Germany 6.6 (4) 4.4 6.6 (5) 6.1

5 Beck, Ulrich Germany 6.3 (5) 1.7 3.3 4.8

6 Foucault, Michel France 2.7 2.4 8.7 (3) 3.5

7 Touraine, Alain France 4.5 1.5 0.8 3.3

8 García Canclini, Argentina 3.1 0.2 5.4 2.8

Néstor

9 Mainwaring, Scott USA 0.1 11.2 (1) 0.0 2.7

10 Weber, Max Germany 2.7 3.7 0.4 2.6

11 Sartori, Giovanni Italy 1.0 5.9 0.0 2.0

12 Bauman, Zygmunt Poland / 2.4 1.5 0.8 2.0

England

13 Huntington, Samuel USA 0.5 6.8 (3) 0.0 2.0

14 Parsons, Talcott USA 2.9 0.2 0.0 1.9

15 Lipset, Seymour USA 0.0 7.8 (2) 0.0 1.8

16 Maturana, Chile 2.0 0.0 3.7 1.8

Humberto

17 O’Donnell, Argentina 0.7 5.6 0.0 1.8

Guillermo

18 Castel, Robert France 1.6 1.0 2.1 1.5

19 Nohlan, Dieter Germany 0.2 6.1 (4) 0.0 1.5

20 Geertz, Clifford USA 1.0 0.0 5.8 1.4

21 Lijphart, Arend Holland 0.1 5.9 (5) 0.0 1.4

22 Martín-Barbero, Spain / 2.2 0.0 0.0 1.4

Jesús Colombia

23 Marx, Karl Germany 1.7 0.7 0.0 1.3

24 Castoriadies, Greece / 1.5 0.5 1.7 1.3

Cornelius France

25 Willke, Helmut Germany 1.9 0.0 0.0 1.2

(1092) (409) (242) (1743)

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Entre los teóricos más La ciencia política, en

citados sólo el 12% son cambio, se diferencia

716

de América Latina... notablemente

Current Sociology 62(5) de la

Esta baja cifra… pauta de autores. La

ratificaría un patrón de sociología y la

división delThere

trabajoare strong similarities between sociology and anthropology regarding antropología the son

authors with

((internacional)), esethe highest quantities of citations; of the top five in each discipline, four arepor los "

dominadas

patrón deja Political science, in contrast, markedly differs from that patterngrandes

a los países

matched. teóricos"

of authors.

centrales la producción (Bourdieu, Luhmann,

Sociology and anthropology are dominated by the ‘big theorists’ (Bourdieu, Luhmann,Giddens),

Habermas,

teórica... lo que podría

Habermas,

entenderse como un Giddens), while in political science middle-range theorists are emphasized,

mientras que en ciencia

authors that

patrón cognitivo de are more closely tied to empirical research on the basis of which they estab-

política la influencia se

lish abstract generalizations (Mainwaring, Lipset, Huntington, etc.). Moreover,

dependencia. while en

concentra in los

sociology and anthropology the major countries of origin of the theorists are teóricos

Europeande alcance

medio, autores más

– Germany, France and England – in political science, the USA dominates: the three ligados

estrechamente

most cited authors in this discipline are of US origin. a la investigación

Among the most cited theorists only 12% are of Latin American originempírica, or have had basados en la

prolonged stays in the region and show a close relationship with it: García cualCanclini,

Ellos ((QUIÉNES

Maturana, O’Donnell, Martín-Barbero, Germani, Cardoso, Laclau, and Hinkelammert. GUIDDENS Y CIA?))

llegan a

One of them – Maturana – additionally, is not properly a social scientist and does not

generalizaciones

make a reflection focused on the social reality of Latin America. Laclau,conceptuales meanwhile,

despite being born in Argentina and concerned with the analysis of his native country, Lipset,

(Mainwaring,

has developed most of his work primarily in the central countries. This low figure of 12%etc.). Por

Huntington,

would ratify the pattern of a division of work in which the theory is basically otraproduced

parte, mientras que

la sociología y la

in the teórica

La producción central countries. The theoretical production from the region is antropologíasecondarily en los

reported,

de la región de Américaso that the theoretical connection is primarily established with the central

países coun-

principales de

tries,una

Latina tiene in what could be understood as a pattern of cognitive dependency. origen de los teóricos

importanciaAll of the above notwithstanding, and although the dominance of the central

secundaria, soncountries

europeos -

en esa medida

in termslaof the development of theory in the field of social science is quite clear, Alemania,

a review Francia e

prioridad teórica guarda Inglaterra - en la ciencia

of the national

relación principalmente production permits us to identify a group of Chilean authors who are fre-

política, la EE.UU.

quently cited; and even though they are not recognized as international-level

con los países theorists,

domina: los tres autores

they have

centrales, en lo que developed abstract arguments of some generality that have achieved

mása citados

signifi-en esta

cant level of

podría entenderse diffusion within national borders and additionally extending their

como ideas,son

disciplina in de origen

un patrón cognitivo

some cases, to other Latin American countries. We could say that they areestadounidense.

‘local theo-

dependiente

rists’ or, more precisely, authors doing theoretical work, since they do not focus entirely

on theory and are not generally recognized as theorists. In this group we considered, due

to being the most cited: Eugenio Tironi, José Joaquín Brunner, Norbet Lechner, Tomás

Moulian, Jorge Larraín, Sonia Montecinos, Pedro Morandé, Fernando Robles and Oscar

Godoy, as ranked according to the number of citations.

If we include these authors in the total group of theorists, they receive 16.8% of all

theoretical references. Although a low proportion, it is not negligible and may have influ-

ence in the national process of generation of knowledge. Whether it actually has this

influence or not is the next question, whose answer I seek to advance using network

analysis. I ask, then, how these producers of knowledge, these local theorists, connect

with theorists from the North and how central or peripheral are their positions in the

resulting theoretical network of the field. For this I appeal to the logic of co-citation

analysis. I consider 73 authors, a sum of 64 international and those nine local authors.

The network analysis applied allows identifying a grouping of central authors such as

Habermas, some others at a clearly peripheral position such as Jon Elster, Harold

Garfinkel and Chantal Mouffe, and a third set in an intermediate position, like Norberto

Bobbio or Richard Sennett. At the center are the greatest theorists: along with one of the

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

El análisis de las redes esta condición se repite,

((de co-citación de 73 al hacer el análisis de

autores, 64 de ellos las redes por fuera de

Ramos Zincke 717

internacionales y, las disciplinas: en

locales, los nueve sociología... al igual que

classics – Weber

restantes)) – there is a group of authors

hay un of the asecond

en cuanto los half of the 20th century:

grupo de autores

Habermas, Bourdieu,de Luhmann,

la Giddens andantropólogos,

Foucault. Butentrealso,

los closely intertwined

segunda mitad del siglo que Lechner aparece

with them, are

XX: Habermas,

several of the ‘local theorists’, prominently

como uno de los

Moulian, Larraín, Brunner,

Lechner and Tironi.

Bourdieu Luhmann, Analyzing the networks separately

“brokers” más by discipline, this situation is

repeated: in sociology,

Giddens y Foucault Moulian occupies a position

destacadosof great centrality in the theoretical

network; in political science, Lechner and Tironi have such a position; and in the field of

entrelazados

((INTER-DEPENDIENT

anthropology Montecinos and Lechner are the central authors, constituting Lechner an

ES DE MANERA

exceptional

SIMÉTRICA Y

case of a political scientist cited by the anthropologists, making him one of

theSUPLEMENTARIA))

most prominent brokers in the whole field.

con teóricos

reconocidos localmente:

Conclusions

Moulian, Larraín,

Brunner,

When observed with a global perspective, considering the results of central indexing

platforms, the data reveal a strong divide between central and peripheral social sciences.

However, when the relations between local social science and global science are observed

from the point of view of the local space of a particular dependent and semi-peripheral

country, Chile, the picture is more balanced than when observed from the perspective of

the central indexing devices. One sees a body of social science that deals intensively with

local situations and requirements, with extensive connections among local authors;

although, on the other hand, paying special attention to what central scientific production

could provide.

The great relevance of the references made to the theorists of central countries is

unquestionable and, in that sense, Chile is part, to a large degree, of the international

division of labor, in which theoretical production is being realized principally in the core

countries. Nevertheless, there is also a group of local authors who do creative work

elaborating abstract propositions, of a theoretical nature, referring fundamentally to local

reality, who are frequently cited, and who are strongly intermingled with the interna-

tional theorists (as confirmed by the co-citation analysis). One might say that the use and

assimilation of international theories happens, to a large degree, within this mediating

and translating network. Therefore, to conclude, on the basis of the relevance that the use

of knowledge from the central countries has, that there is a situation of cognitive depend-

ence would be exaggerated or at least an excessively simplified statement. If a central

characteristic of cognitive dependence is to use knowledge that is inadequate for the

local reality, which has the imprint from the central countries, without a filter, translation

or criticism (Alatas, 2001, 2003), it could be argued that within this local circle of theo-

retical development such a creative and adaptive process is occurring. As a matter of fact,

a review of the works of said authors leads us to the conclusion that among them such

translation work – critical and adaptive – is really taking place. These results in the

Chilean case contradict some of the statements made under the idea of cognitive depend-

ence, allowing us to criticize the generalizations made about it and could further discus-

sion of this notion.

An historical review of social science in Chile allows us to confirm that from the

beginning, together with the institutionalization of this way of generating knowledge,

there have been such receptive, adaptive and creative processes (Barrios and Brunner,

1988; Beigel, 2010, 2011; Brunner, 1988; Franco, 2007). The period between 1960 and

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

718 Current Sociology 62(5)

1973 is a conspicuous example in this regard, with a significant production of social sci-

ence knowledge, focused on the local reality and with a profuse use of theories coming

from the central countries (Beigel, 2010).7 Around 1980, also, there is a significant theo-

retical elaboration and debate trying to develop ways to analyze the social reality of

Chile under dictatorship. The field of local social science has conserved endogenous

capabilities for generating knowledge, although it is situated within an international

framework of inequality regarding the flow and appreciation of that knowledge.

A matter of concern regarding the observed pattern of global connections is the fact

that the local production is not sufficiently valued and projected on a global level and that

the local institutions do not help to increase its value and international projection, but

rather they place obstacles in the path of its achievement. The problem is this and not the

pronounced utilization of international publications. The central indexes, like SSCI and

Scopus, despite the fact that they began with a definitely local character, referring to

countries like the USA and UK, have defined themselves from the start as global, as

representing a science authentically universal, covering the whole world, whereas, in

contrast, the regional indexes of Latin America, like Scielo and Latindex, are conceived

and projected as local, and are used by the countries of the region – definitely so in Chile

– as second class indexes. In such a way, unintentionally, and despite all of the reiterated

public discourse against the situation of scientific inequality, academic institutions

become an accomplice in maintaining and reproducing the distinction between central

science (coincidental with what is produced in the central countries) and peripheral sci-

ence (correlated with what is produced by the peripheral countries).

Consequently, if there is no change in the central and regional indexation procedures

or in the ranking criteria employed by scientific institutions in Chile, the inequality

between central and peripheral science will remain. On the other hand, the strong empha-

sis given to global science by universities and public funding institutions is a threat to the

current local focus and relative autonomy of the social sciences in this country.

Acknowledgements

I thank Andrea Canales and Stefano Palestini for their valuable collaboration in the research, and

Fernando Valenzuela, Fernanda Beigel and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

This work was part of a research supported by the National Council of Science and Technology of

Chile under Fondecyt grants number 1070814 and 1121124.

Notes

1. For advertising reasons, Thomson currently hosts its products under the name ‘Web of

Science’, and Elsevier under the name of ‘Sciverse Scopus’.

2. The respective fund for scientific research (Fondecyt) was created in 1982 and throughout

its 30 years of existence has financed more than 15,000 projects, from all disciplines, for a

total of about US$1,500 million. The amounts invested have steadily grown since the late

1980s and since 2006 have had an accelerated growth, so that in 2011 the awarded amounts

where three times larger than the 2005 funds. For its part, the policy of putting ISI publica-

tions as the required standard has had its effects: in the late 2000s, the annual number of ISI

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 719

publications more than doubled that of the beginning of the decade and in the period 2007–

2011, 23% of all ISI publications in the country came from projects funded by Fondecyt

(Fondecyt, 2012).

3. In Chile there are 59 universities and numerous research centers, however approximately

80% of ISI publications are generated by six universities (Baeza, 2010: 161).

4. We do this from a mode-2 network, of texts and theorists, and then we reduce it to a mode-1

of theorists. For this analysis we have used a variety of software programs: ORA, Ucinet and

Pajek.

5. Additionally, within Conicyt, the political science study group is the group that, for evaluat-

ing researchers, gives more qualifying points to ISI publications, well beyond the points given

to Scielo or Latindex publications.

6. The list of theorists includes producers of grand theory, middle-range theories and theoreti-

cal generalizations. There is no difference between positive and negative citations, since all

involve establishing a connection to the respective author, even if it is only to criticize him.

Moreover, the links with critical content are very scarce.

7. For a broader and deeper discussion of the relation between autonomy and dependence, see

Beigel (2010), covering the period between 1950 and 1980, referring to Chile and Argentina.

References

Alatas S (2001) The study of the social sciences in developing societies: Towards and adequate

conceptualization of relevance. Current Sociology 49(2): 1–19.

Alatas S (2003) Academic dependency and the global division of labour in the social sciences.

Current Sociology 51(6): 599–613.

Ammon U ( 2011) La hegemonía del inglés. In: UNESCO (ed.) Informe sobre las ciencias sociales

en el mundo. Las brechas del conocimiento. México: UNESCO and Foro Consultivo, pp.

159–160.

Archambault E and Larivière V (2011) Los límites de la bibliometría en el análisis de la literatura

en ciencias sociales y humanidades. In: UNESCO (ed.) Informe sobre las ciencias sociales

en el mundo. Las brechas del conocimiento. México: UNESCO and Foro Consultivo, pp.

263–267.

Babones S and Alvarez-Rivadulla MS (2007) Standardized income inequality data for use in cross-

national research. Sociological Inquiry 77: 3–22.

Baeza J (2010) El caso de Chile. In: Santelices B (ed.) El rol de las universidades en el desarrollo

científico y tecnológico. Educación superior en iberoamérica. Informe 2010. Santiago, Chile:

Centro Universitario de Desarrollo (CINDA) and Universia, pp. 153–162.

Barrios A and Brunner JJ (1988) La sociología en Chile. Instituciones y practicantes. Santiago,

Chile: Flacso.

Beigel F (2010) Autonomía y dependencia académica. Universidad e investigación científica en

un circuito periférico: Chile y Argentina (1950–1980). Buenos Aires: Editorial Biblos.

Beigel F (2011) Misión Santiago. El mundo académico jesuita y los inicios de la cooperación

internacional católica. Santiago, Chile: LOM Ediciones.

Brunner JJ (1988) El caso de la sociología en Chile. Formación de una disciplina, Santiago, Chile:

Flacso.

Burawoy M, Chang MK and Feiy-yu Hsieh M (2010) Facing an Unequal World: Challenges for

a Global Sociology (3 vols). Tapei, Taiwan: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica and

International Sociological Association.

Burke P (2002) Historia social del conocimiento. De Gutenberg a Diderot. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

720 Current Sociology 62(5)

Clemens E, Powell W, McIlwaine K and Okamoto D (1995) Careers in print: Books, journals, and

scholarly reputations. American Journal of Sociology 101(2): 433–494.

Connell R (2007) Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

De Bellis N (2009) Bibliometrics and Citation Analysis. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press.

Degenne A and Forsé M (2004) Les Réseaux sociaux. Paris: Armand Colin.

Farías F (2004) La sociología chilena en la década de los noventa. Cinta de Moebio 19: 55–66.

Fondecyt (2012) Fondecyt 30 años. Santiago, Chile: Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y

Tecnológico.

Fourcade M (2009) Economists and Societies: Discipline and Profession in the United States,

Britain and France, 1890s to 1990s. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Franco R (2007) La Flacso clásica (1957–1973). Vicisitudes de las ciencias sociales latinoameri-

canas. Santiago, Chile: Flacso y Catalonia.

Fuentes C and Santana G (2005) El ‘boom’ de la ciencia política en Chile: Escuelas, mercado y

tendencias. Revista de Ciencia Política 25(1): 16–39.

Garretón MA (2005) Social sciences and society in Chile: Institutionalization, breakdown and

rebirth. Social Science Information 44 (2 & 3): 359–409.

Gingras I and Mosbah-Natanson S (2011) ¿Dónde se producen las ciencias sociales?. In: UNESCO

(ed.) Informe sobre las ciencias sociales en el mundo. Las brechas del conocimiento. México:

UNESCO and Foro Consultivo, pp. 153–158.

Gmür M (2003) Co-citation analysis and the search for invisible colleges: A methodological evalu-

ation. Scientometrics 57(1): 27–57.

Guédon JC (2011) El acceso abierto y la división entre ciencia ‘principal’ y ‘periférica’. Crítica y

Emancipación 3(6): 135–180.

Lander E (2004) Universidad y producción de conocimiento: Reflexiones sobre la colonialidad del

saber en América Latina. In: Sánchez I and Sosa R (eds) América Latina: Los desafíos del

pensamiento crítico. México: Siglo XXI Editores, pp. 167–179.

Merton RK (1973) The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Mignolo W (2003) Historias locales/diseños globales. Colonialidad, conocimientos subalternos y

pensamiento fronterizo. Madrid: Ediciones Akal.

Mignolo W (2004) Colonialidad global, capitalismo y hegemonía epistémica. In: Sánchez I and

Sosa R (eds) América Latina: Los desafíos del pensamiento crítico. México: Siglo XXI

Editores, pp. 113–137.

Palestini S, Ramos C and Canales A (2010) La producción de conocimiento antropológico social

en el Chile post-transición: Discontinuidades del pasado y debilidades del presente. Estudios

Atacameños 39: 101–120.

Ramos C (2005) Cómo investigan los sociólogos chilenos en los albores del siglo XXI: Paradigmas

y herramientas del oficio. Persona y Sociedad 19 (3): 85–119.

Ramos C and Canales A (2009) Political science in Chile: Positivistic hegemony, institutional

power, and discipline isolation. In: XXI IPSA World Congress of Political Science, Santiago,

Chile, 12–16 July 2009.

Rehren A (2005) La evolución de la ciencia política en Chile: Un análisis exploratorio (1980–

2000). Revista de Ciencia Política 25(1): 40–55.

Ríos M, Godoy L and Guerrero E (2003) ¿Un nuevo silencio feminista? Santiago de Chile: Centro

de Estudios de la Mujer/Editorial Cuarto Propio.

Rodríguez L (2010) Las revistas iberoamericanas en Web of Science y Scopus: Visibilidad inter-

nacional e indicadores de calidad. In: VII Seminario Hispano-Mexicano de Investigación en

Bibliotecología y Documentación, Ciudad de México, 7–9 abril 2010.

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

Ramos Zincke 721

Scott J (2000) Social Network Analysis. A Handbook. London: Sage.

Trindade H (ed.) (2007) Las ciencias sociales en América Latina en perspectiva comparada.

México: Siglo XXI Editores.

UNESCO (ed.) (2011) Informe sobre las ciencias sociales en el mundo. Las brechas del cono-

cimiento. México: UNESCO and Foro Consultivo.

Vessuri H (2008) El futuro nos alcanza: Mutaciones previsibles de la ciencia y la tecnología. In:

Gazzola AL and Didriksson A (eds) Tendencias de la educación superior en América Latina

y el Caribe. Caracas: IESALC-UNESCO, pp. 55–86.

Wassermann S and Faust K (1994) Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author biography

Claudio Ramos Zincke, PhD in sociology, is professor at Alberto Hurtado University, Chile. His

main research interest is the study of science and technology, focused on social sciences in Chile.

Currently, he is investigating the processes of social measurement that occur inside the state and

the construction and diffusion of sociological narratives, alongside the performative consequences

of both processes. He has recently published the book El ensamblaje de ciencia social y sociedad.

Conocimiento científico, gobierno de las conductas y producción de lo social (2012).

Résumé

Cet article analyse les connexions entre les sciences sociales chiliennes et la connaissance

produite dans les pays du centre, en les comparant avec les connexions existantes entre

ce même pays et les autres pays latino-américains, tout en accordant une attention

particulière au domaine théorique. Ce travail s’appuie sur l’analyse du contenu de

publications académiques et l’analyse du réseau social d’une base de données de plus

de trente milles références bibliographiques, issues de projets de recherche publiés par

des chercheurs en sciences sociales chiliens dans des revues et des livres au Chili et

à l’extérieur, durant une période de sept ans dans la première décennie de ce siècle.

Les résultats montrent que le niveau de connexions avec les autres pays de l’Amérique

Latine est bas mais que les communications entre les auteurs chiliens sont relativement

nombreuses, surtout celles qui concernent un groupe de théoriciens locaux qui

occupent des positions centrales dans le réseau. Il ne semble pas qu’il s’agisse ici d’une

forme de dépendance cognitive bien qu’elle se produise dans le contexte d’une science

internationale caractérisée par une remarquable inégalité.

Mots-clés

Communication scientifique, dépendance cognitive, réseau social, régulation scientifique,

sciences sociales, citation

Resumen

Este artículo analiza las conexiones de las ciencias sociales en Chile con el conocimiento

que se produce en los países centrales, en comparación con las establecidas en el mismo

país y en otros países de América Latina, prestando especial atención a las conexiones

con respecto a la teoría. Se basa en el análisis de contenido de publicaciones académicas

y en el análisis de redes sociales aplicado a una base de datos de casi treinta mil

referencias bibliográficas generadas por este proyecto de investigación del universo de

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

722 Current Sociology 62(5)

investigaciones publicadas por científicos sociales chilenos en revistas y libros, tanto en

Chile como en el extranjero, en un período de siete años en el primer década de este

siglo. Los resultados muestran que, en relación con las comunicaciones internacionales,

existe un bajo nivel de conectividad con otros países de América Latina, pero que las

comunicaciones entre autores chilenos son relativamente importantes y en particular

los que tienen un grupo de teóricos locales que ocupan posiciones centrales en la

red. Este no parece ser un patrón de dependencia cognitiva, aunque se produce en el

contexto de una ciencia global que se caracteriza por una desigualdad notable.

Palabras clave

Comunicación científica, dependencia cognitiva, red social, regulación científica, ciencias

sociales, citación

Downloaded from csi.sagepub.com at University of Lausanne on November 6, 2014

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Moon Landing ConspiracyDocument17 pagesMoon Landing ConspiracyElianeSalamNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- SAP FICO Resume - Exp - 3.5 YearsDocument3 pagesSAP FICO Resume - Exp - 3.5 Yearsranga67% (3)

- 2014 Macdonald PeerReviewDocument17 pages2014 Macdonald PeerReviewbherrera1No ratings yet

- 2 - PaintingDocument26 pages2 - PaintingELLEN MASMODINo ratings yet