Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anita Chan China Free Labour Force

Uploaded by

Dileep Menon0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views22 pagesLabour Markets

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLabour Markets

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views22 pagesAnita Chan China Free Labour Force

Uploaded by

Dileep MenonLabour Markets

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 22

nan lersity] at 19:19 23 September 2014

Dowaloaded by (Australi

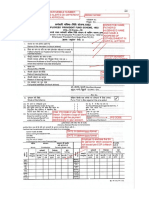

csapbri4.cnd 28/06/2000 13:45 Page 260 é

14

Globalization, China’s Free

(Read Bonded) Labour Market, and

the Chinese Trade Unions

ANITA CHAN

Once largely cut off in the days of Mao from the world’s capitalist

economy, in the two decades since the 1970s China has out-

competed all of its Asian neighbours in attracting foreign direct

investment (FD), becoming the world’s second largest recipient of

FDI after the United States. Formerly largely self-reliant, China has

become a huge exporter of labour-intensive consumer goods. Many

teasons account for the scale and speed at which China has

obtained investment capital and penetrated international export

markers. One that is frequently cited is that Chinese labour is cheap

compared to most of its East and South-East Asian neighbours.!

From an almost complete absence of a labour market two decades

ago — when factory jobs were strictly allocated by the authorities —

China now has a relatively flexible labour market, It also has a

geographically mobile labour force, an estimated ‘floating

population’ of at least 70 million rural people on the move all over,

the country in search of urban jobs (Beja, 1996). This abundant

supply of cheap labour will help ensure thar China remains

internationally competitive for some years to come.

‘Manufacturers from elsewhere in Asia who have established

factories in Southern China repeatedly assert that if labour costs and

work conditions cannot be kept strictly in line, they will move their

facilities to Vietnam or Indonesia (Chan, 1998a). Their joint venture

partners in China normally are local government bodies, who find

1tin their own interests to try to sustain a profitable environment for

+he firms. They have become willing participants in an effort to keep

a lid on the wages and conditions of labour of the migrant workers

who have flooded into Southern China from poorer inland

provinces in search of work. This part of the new labour market has

deen placed at the service of the forces of globalization. The local

Downloaded by [Australian ‘eongaiversion at 19:19 23 September 2014

Gsapbed.get 28/06/2008 23.45 Page 262

CHINA'S FREE (READ BONDED) LABOUR MARKET 26],

authorities’ capacity to provide this has been enhanced by decentral-

ization of the political system, level by level — to the province, city,

county, township, village and down to the workplace (Zweig, 1995).

Despite this decentralization, the central government has

attempted to keep pace with China’s rapid economic transformation

by issuing Party fiats and by enacting a large number of laws over

the past decade. However, these high-level efforts have often been

given a local twist or ignored. As far as labour-management

relations are concerned, as will be seen in the following pages, a

deregulated situation has often led to abusive management practices,

deteriorating labour standards and violations of labour laws. These

malpractices first appeared in the foreign-funded sector,

predominantly in the firms established by investors from Hong

Kong, Taiwan and Korea. These are concentrated in the coastal

provinces, and in a ripple effect, their management techniques have

spread to the inland regions and into the state sector.

Various scholars have described how China’s economic reforms

have affected Chinese enterprises and, in turn, workers (O'Leary,

1992; Ng and Ip, 1994; Warner, 1996; Zhu and Campbell, 1996;

Leung, 1997). This contribution will focus on how globalization

and a deregulated economic situation affect China’s ‘free’ labour

market and conditions of work. It will also examine the Chinese

unions’ attempts to adjust to the new developments in this ‘free?

labour market.

‘Free’ is deliberately put in inverted commas because the thrust

of my argument is that the Chinese labour market introduced by

the economic reforms is ‘free’ only in a superficial way. To be sure,

most workers are no longer constrained by the Maoist system of

allocating people to jobs under « planned command economy. Yet,

large numbers of people today are constrained instead in the sense

that they have become bonded labour. As shall be observed, two

separate types of bonded labour have emerged in China: one in the

non-state sector (especially in many of the labour-intensive foreign-

funded joint ventures) and another in the state-owned indus

‘THE ‘FREE’ LABOUR MARKET AND BONDED LABOUR

Bonded Labour in the Non-State Sector

Very large numbers of peasant migrants from Cl

aA

Iniversity] at 19:19 23 September 2014

Downloaded by (Australian Nations

Hl

Ccaptertignd 29/o0/as0e 2345 rage 262.

262 GLOBALIZATION AND LABOUR IN THE ASIA PACIFIC

interior provinces fill most of the production-line positions in the

factories that have sprouted in the coastal regions, For example, in

the industrially booming delta region of Guangdong in Southern

China, about 90 per cent of production line workers are migrants.

In the less developed regions where locals ae still willing to work

at very low wages they work alongside such migrants on

production lines.’ But China’s household registration (bukou)

system ensures that the large numbers of migrant workers do not

enjoy the same status as the local residents (Mallee, 1995: 1-29).

For social control purposes, the central government during the

‘Maoist period curtailed geographic mobility through this system, in.

particular controlling rural-urban migration. Even today, the

household registration system acts as a ‘sluice gate’ regulating the

rural-urban flow. Ic allows more workers into the economic zones

and economically booming areas when they are needed and drives

them out when infrastructure becomes stretched to the limit or

when economic recessions strike. Their resicential status is similar

to that of foreign ‘guest workers’ subject to tight ‘immigration’

controls. To leave their villages peasants are required to apply for a

permit from their local government. To stay in any other district

they have to apply to the local police station for a temporary

residential permit. When they are offered employment they need to

secure a contract with an employer, and ther application to work

then has to be approved by the local labour bureau, which issues a

work permit. Periodically, the police carry out raids to round up

those who do not possess the temporary residential and work

permits (Zhao, 1996: 42-6). Those caught are harassed, humiliated

and mistreated, thrown into detention centres and then deported

from the cities.

Most of those who are allowed to stay live in crowded

dormitories provided by the factories, or in shanties. They are not

entitled to any of the benefits enjoyed by local residents, such as

social welfare, nor may they bring their spouses or children with

them. Once their labour is no longer required they are supposed t0

0 back to their place of origin.* Socially, they are discriminated

against by local residents (Chan et al., 1992: 299-308). In the face

of all of these impediments, their work experience is precarious

and exploitative (see, for example, Gao, 1994; Solinger, 1998).

The household registration system provides fertile conditions

for the creation of a system of forced and bonded labour. For a

A

iniversity) at 19:19 23 September 2014

Downloaded by [Australian Nation:

Jesapprza.qxa 29/08/2000 13:45 Page 263 é

CHINA'S FREE (READ BONDED) LABOUR MARKET 963,

start, workers are required to buy their temporary work permit in

one lump sum. In places where the cost of the permit is too high

for the migrants to afford, the factory often pays for it on behalf of

the worker

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Carswell LabouringDocument27 pagesCarswell LabouringDileep MenonNo ratings yet

- Transforming The Company Manage Change, Compete Win by Colin Coulson-ThomasDocument419 pagesTransforming The Company Manage Change, Compete Win by Colin Coulson-ThomasDileep MenonNo ratings yet

- Help Form19Document3 pagesHelp Form19Dileep MenonNo ratings yet

- Age of TennysonDocument36 pagesAge of TennysonDileep MenonNo ratings yet

- Towards The Romantic RevivalDocument17 pagesTowards The Romantic RevivalDileep MenonNo ratings yet

- Ananthanarayan and Paniker's Textbook of MicrobiologyDocument672 pagesAnanthanarayan and Paniker's Textbook of MicrobiologyDileep MenonNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)