Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Legitimacy Industry Maturity and Foresight

Uploaded by

Aladdin PrinceCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Legitimacy Industry Maturity and Foresight

Uploaded by

Aladdin PrinceCopyright:

Available Formats

Strat.

Change 23: 171–183 (2014)

Published online in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/jsc.1969 RESEARCH ARTICLE

‘Space of Possibles’? Legitimacy, Industry Maturity, and

Organizational Foresight1

Lindsay Stringfellow

University of Exeter Business School, UK

Mairi Maclean

University of Exeter Business School, UK

The roots of the awareness and

perception from which T he dispositions and invisible cognitive structures central to organizational foresight

are more likely to emerge in young or transforming industries, which are less

constrained by the need to achieve institutional legitimacy.

organizational foresight emerge

are often unconscious, being

embedded in invisible cognitive

structures which organize

practices. Introduction

Organizational foresight can be viewed as a technical, rational process involving

The emergence of organizational

the analysis of an organization’s environment by its management, who anticipate

foresight is intimately linked to

the institutional context of the and design strategies for the future (Constanzo, 2004; Constanzo and MacKay,

firm, the modes of legitimacy 2009; Tsoukas and Shepherd, 2004a,b). Another perspective that we adopt in this

which dominate that environment, paper sees organizational foresight as the accumulation of microscopic emergent

and how balanced these actions that together conspire to make the future of the organization (Cunha,

conditions are with the subjective 2004; Tsoukas and Chia, 2002). We build on the practice perspective of foresight

disposition of the organization.

as a social process through which organizations act on the present in order to make

The stability and convergence that sense of possible futures (Andriopoulos and Gotsi, 2006; Loveridge, 2008). Fore-

characterize mature industries sight is a web of decisions made by agents with a personal stake in the outcomes,

orientate organizations toward

and it has been linked with the ability to be a vigilant sensor, a skilled improviser,

institutional legitimacy and the

and able to cope with local problems as they emerge (Chia, 2004a,b). An organi-

conservation of existing social

relations and practices. zation’s stake in the outcomes, however, will vary according to its own character-

istics and those of the industry in which it operates, and some organizations may

seek to maintain the status quo. Often the development of foresight emerges

subconsciously, from the relationship of the context of the organization and its

practices to the pathways of possibility inscribed in invisible cognitive structures,

and it is this aspect of foresight that we aim to uncover.

In this paper, we draw on the work of the pre-eminent French sociologist

Pierre Bourdieu (1977, 1990) and his theory of practice in order to explore how

organizational foresight emerges in relation to social structure. Bourdieu’s work

1

JEL classification codes: M10, M11, M14.

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

Strategic Change: Briefings in Entrepreneurial Finance DOI: 10.1002/jsc.1969

172 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

provides a relational framework for multilevel analysis practice shed light on issues of legitimacy and organiza-

that overcomes the dualities of structure and agency, and tional foresight, before discussing our implications for

which is inherently focused on practice. It thereby allows practice and research.

a deep understanding of foresight to emerge, one that

appreciates the ‘reweaving of actors’ webs of beliefs and

habits of action to accommodate new experiences’ The legitimacy landscape

(Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 567). Bourdieu’s social theory If foresight is linked to learning and sense making (Tsoukas

centers on practice and reproduction, which link with the and Shepherd, 2004a; Weick, 2001) and the capacity to

idea of foresight, acknowledging that: grasp the relevant features of social currents likely to shape

the direction of future events (Whitehead, 1933), it is also

. . . all actors are conditioned by the past — that is, discernibly interwoven with issues of legitimacy. Legiti-

by the particular trajectories they have historically macy denotes the conformation of an entity with the

followed — what is possible in the present and in the norms, values, and expectations of the social context

future cannot ignore what has gone on before — social within which it exists (Oliver, 1996; Suchman, 1995). It

systems have memory. (Tsoukas and Shepherd, is inherently a social construction, which signals a subjec-

2004b: 139) tive judgment of acceptance, appropriateness, and desir-

ability, allowing organizations to access the resources

We also draw on theories of legitimacy to conceptual- needed to survive and grow (Zimmerman and Zeitz,

ize how organizations embedded in mature versus emerg- 2002: 414). Legitimacy is therefore a precondition for

ing industries have different possibilities to ‘penetrate and organizational survival, and tempers the sphere of oppor-

transgress established boundaries’ (Chia, 2008: 27). tunities open to firms. It is an important constituent of

Drawing on recent empirical and conceptual contribu- organizational foresight, since it helps organizations to

tions in entrepreneurship, we develop a Bourdieusian per- understand the nature of the challenges, particularly in

spective of foresight as the emergence of a ‘space of gauging the strategic usefulness of passive conformity or

possibles’ (Bourdieu, 1996b: 236), which creates the pos- active manipulation (Oliver, 1991). Perceiving future

sibility for agency, and we present a model of the dynam- changes and foreseeing emerging challenges is a primary

ics of organizational foresight across more or less strategy for maintaining legitimacy, and a range of per-

institutionalized environments. ceptual strategies is needed to monitor the cultural envi-

With this agenda in mind, we have structured the ronment and assimilate elements into the organization’s

paper as follows. In the first section, we outline the theo- processes (Suchman, 1995). Similarly, organizational fore-

retical foundations of the legitimacy literature and how sight indicates ‘the organisational ability to read the envi-

different perspectives relate to organizational foresight. ronment — to observe, to perceive — to spot subtle

Next, we detail research in entrepreneurship to illuminate differences’ (Tsoukas and Shepherd, 2004b: 140).

further the role of context and field dynamics on processes The legitimacy literature proposes two main approaches

of legitimation and the practice of foresight. Following to managing legitimacy, strategic and institutional, and

this, we discuss Bourdieu’s theoretical framework and how these contrasting perspectives can create conflicting

the concept of foresight relates to habitus and the space accounts of legitimacy (Oliver, 1991). The strategic

of ‘possibles’ within fields. Finally, we return to the entre- approach to legitimacy sees competition and conflict

preneurship literature and show how recent conceptual among social organizations as involving the conflict

and empirical developments using Bourdieu’s theory of between systems of beliefs or points of view (Pfeffer, 1981:

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 173

9). The strategic perspective depicts legitimacy as a foresight also requires a sense of time, a way of relating

resource that organizations manage and extract instru- past, present, and future, and a recognition that ‘the future

mentally from their environments in order to achieve their has no place to come from but the past’ (Neustadt and

goals (Suchman, 1995). Institutional legitimacy, by con- May, 1986).

trast, emphasizes how culture directs organizations to Strategic legitimacy concerns active behavior, and the

conform to generally accepted norms, values, and beliefs manipulation and deployment of evocative symbols to

(Scott, 1994). Therefore, legitimacy is not an operational garner legitimacy, for instance, through improvising or

resource, but rather a set of constitutive beliefs externally resource combination behaviors (Tornikoski and Newbert,

constructed which make the organization appear natural 2007). The proactive and managerial nature of strategic

and meaningful (Suchman, 1995). Subconscious adapta- legitimacy would make the practice of organizational fore-

tion means that organizations reflect similar forms and sight one aspect of the development of this resource.

practices, and isomorphic processes limit the potential for However, it is also true that strategic efforts often remain

resistance or strategic action (DiMaggio and Powell, a symbolic reaction to legitimacy efforts, and ‘ . . . orga-

1983). nizations deem it as important simply to “appear” consis-

Institutional legitimacy appears counter-intuitive to tent with the normative demands from their societal

organizational foresight, since isomorphic processes are context’ (Palazzo and Scherer, 2006: 74). Palazzo and

associated with the homogenization of structural forms Scherer (2006: 74) suggest that the strategic approach is

within organizations (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983) and a overly focused on pragmatic legitimacy, which assumes

diminishing capacity to respond to uncertain future that organizations have ‘the power to strategically influ-

changes (Scott and Meyer, 1991). The paradox of embed- ence their societal context thus manipulating the process

ded agency means that actors are rooted in institutional of legitimacy ascriptions.’ Strategic manipulation does not

fields with shared cognitive frames, which makes it diffi- help to create moral legitimacy, based on conscious moral

cult to envisage new practices. As Weick (2001: 136) puts judgments, or cognitive legitimacy, which relates to the

it, as time passes organizations acquire ‘a trained incapac- ways in which the societal context regards an organization

ity to see the world differently.’ The solution to this and its output, procedures, structures, and leader behavior

paradox is that agency is distributed in the structures (Suchman, 1995).

actors have created, meaning that embedding structures The legitimacy literature suggests that the context in

can provide a platform for the unfolding of entrepreneur- which organizational foresight emerges is socially and cul-

ial activities (Garud et al., 2007). Institutional entrepre- turally embedded. The likelihood of foresight arising, and

neurs break with existing rules and practices associated the relative benefits of conformance, selection, manipula-

with the dominant institutional logics, and ‘leverage tion, and creation efforts (Suchman, 1995; Zimmerman

resources to create new institutions or to transform exist- and Zeitz, 2002) are conditioned by the nature of the

ing ones’ (Maguire et al., 2004: 657). Institutional entre- environment, the characteristics of the organization, and

preneurship can therefore link institutional views of the process through which legitimacy is managed and

legitimacy and organizational foresight, which entails the sustained (Kostova and Zaheer, 1999). Uncertainty, tur-

capacity to imagine alternative possibilities. Institutional bulence, uniqueness, and complexity in the environment

entrepreneurship requires the ability ‘to contextualize past may provide openings for organizations to strategically

habits and future projects within the contingencies of put forth practices or models (Constanzo, 2004; Zimmer-

the moment’ (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998: 963) if exist- man and Zeitz, 2002) but in mature, institutionalized

ing institutions are to be transformed. Organizational contexts the strategic options may be quite different

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

174 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

(Suddaby and Greenwood, 2005). In the following neurial firms in reacting to change but, thus far, the legiti-

section, we draw on the legitimacy literature in entrepre- mating capabilities of established ventures are often

neurship to illuminate the role of organizational context perceived as reactionary rather than visionary (Dewald

(Welter, 2011). and Bowen, 2010).

Research has been increasing into the dynamics of

entrepreneurial survival in new and emerging industries,

Legitimacy in different entrepreneurial contexts although the particular role of organizational foresight in

Entrepreneurship research tends to focus on the dynamics relation to strategic action is relatively underexplored

of legitimation for new ventures, and often the context is (Drori et al., 2009). New ventures entering an emerging

an emerging rather than an established industry. New field face two legitimacy dilemmas: establishing the cred-

ventures lack indicators of legitimacy such as past perfor- ibility of their own venture, and inventing and reinventing

mance, making it vital that they foster an impression of the legitimacy of the field in the context of a dynamic,

credibility and viability in order to persuade resource turbulent environment. David et al. (2013) found that

holders to commit to the venture (Packalen, 2007; Zim- actors in emerging fields could not leverage logics, posi-

merman and Zeitz, 2002). Drawing on the notion of tions, and collectivities within their field to establish

strategic legitimacy, researchers have examined how the legitimacy, and must instead draw on external fields, and

liability of newness is overcome using impression manage- seek the support of authorities and elites. Nicholls (2010:

ment (Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001), social networks 612) found that ‘the pre-paradigmatic status of a field

(Smith and Lohrke, 2008), and symbolic management allows resource-rich actors to leverage power over the

(Zott and Huy, 2007). From this perspective, there are legitimating processes that characterize progress toward

manageable processes and practices that garner organiza- institutionalization,’ which has significant implications

tional foresight and enhance legitimacy, such as reflexivity, for non-dominant field actors. It has been proposed that

organizational restructuring, and ‘the sensitivity of the organizational foresight in high-velocity environments

entrepreneur to changes in business conditions and their requires proactiveness and ‘ephemeral, illusionary and

willingness to act on them’ (Fuller et al., 2008). The insti- futuristic business models’ that can cope with a fast-

tutional legitimacy of new ventures is less explored, changing technological, competitive, and regulatory envi-

although Tornikoski and Newbert (2007) found it to be ronment (Bourgeois and Eisenhardt, 1988).

less significant in emergence than strategic management. The dearth of entrepreneurship research that examines

There is relatively less attention paid in the entrepre- legitimacy in mature fields may be explained by the fact

neurship literature to the ongoing need to maintain legiti- that entrepreneurship tends to highlight novelty, and dis-

macy in established ventures. Such firms also need to ruptions generated by creative destruction (Shane and

maintain a relationship with a fragmented environment, Ventakaraman, 2000). Garud et al. (2007) note that,

heterogeneous demands, and the environmental unre- from a sociological perspective, change associated with

sponsiveness linked to isomorphism (DiMaggio and entrepreneurship involves deviations from a specified

Powell, 1983; Suchman, 1995). Literature exploring the norm, and that in general entrepreneurship takes the per-

concept of ‘entrepreneurial foresight’ has pointed out that spective of change over continuity. By contrast, it is gener-

a key focus of importance for entrepreneurial activities is ally acknowledged that in mature industries roles and

mastering the art of continued anticipation, proactiveness, relationships are relatively stable and that over time power

and innovation (Fontela et al., 2006). The practice of relations and coalitions will have been established (DiMag-

organizational foresight should assist developing entrepre- gio and Powell, 1983). Mature fields also tend to be more

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 175

stratified, with elite firms able to sustain a logic that is ‘socially rare and distinctive tastes, skills, knowledge and

favorable to their interests, which makes entrepreneurial practices’ (Holt, 1998: 3). The cultural elite dominate the

efforts to gain legitimacy more arduous (Lounsbury and field, retaining the power to classify and categorize literary

Glynn, 2001). In mature fields, entrepreneurship may be work, which indicates status or symbolic capital, and the

slowed down by the need to attend to issues of institu- elite act as gatekeepers to the field’s social networks and

tional legitimacy, and this is likely to impact on the emer- memberships, thereby creating social capital (Anheier

gence of organizational foresight. In order to explore et al., 1995).

further the intricacies of legitimation and organizational The third element of Bourdieu’s theoretical triad con-

foresight in different institutional and environmental con- cerns habitus, which consists of ‘systems of durable, trans-

texts, we now turn to Bourdieu and introduce his rich posable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to

system of thought as a tool for explaining the multidi- function as structuring structures’ (Bourdieu, 1977: 72).

mensional and situated nature of organizational practice. Habitus is key to understanding the relationship between

action and structure, representing a subjectively embodied

disposition or generative social psychological structure

Bourdieu’s practice perspective that does not determine action, but rather orientates actors

Research momentum has been building in recent years in to particular ways of thinking, feeling, and acting, thereby

management and organization studies into the role of guiding their goals and strategies. Contrary to criticisms

situated practice in explaining social phenomena (De of habitus as overly structuralism (King, 2000), it repre-

Clerq and Voronov, 2009a; Maclean et al., 2012a; Ozbil- sents an ‘active generative matrix of action’ (Lizardo,

gin and Tatli, 2005). Practice theory links social structure 2009: 9) and a cognitive structure capable of producing

with shared understandings, and focuses on how actors and sustaining institutional action (Fararo and Butts,

engage in iterative ‘wayfinding’ (Chia, 2004c) and impro- 1999). Thus, habitus is intimately related to issues of

vise their route through ‘a world that remains in a con- legitimacy, as it is this ‘feel for the game’ that creates cul-

stant state of flux’ (De Clerq and Voronov, 2009a; Tsoukas tural alignment between individuals and the field in which

and Chia, 2002). Bourdieu’s theory of practice offers a they operate. Foresight is also congruous to habitus, given

conceptual framework that can accommodate the rela- ‘[T]he practices produced by the habitus [are] the strat-

tional and institutional features that orientate the cultiva- egy-generating principle enabling agents to cope with

tion of organizational foresight. unforeseen and ever-changing situations’ (Bourdieu,

Bourdieu’s work centers on a theoretical triad consist- 1977: 72).

ing of field (representing the social structure), the various To explore this link further, organizational foresight

forms of capital (which are related to power relations), and should be seen as rooted in cognition (Das and Teng,

the habitus (disposition) (Dobbin, 2008; Malsch et al., 1999) and a sensitivity to tensions and ‘unconscious meta-

2011). Agents are in constant competition for capital physics’ shaping dominant habits of thought (Whitehead,

(which exists in economic, cultural, social, and symbolic 1933). Habitus explains our capacity to ‘think with the

forms) within dynamic fields, which are distinct social body’ and to ‘know without concepts’ (Bourdieu, 1984:

spaces where different forms of capital dominate (Bourdieu, 471), which results in doxa. Doxa implies a complicity

1986). For example, in the literary field, writers of popular between objective structures and embodied structures,

fiction gain access to economic capital that may be denied and ‘an adherence to relations of order which, because

to the literary elite, yet the field remains orientated toward they structure inseparably both the real world and the

cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1993), which consists of thought world, are accepted as self-evident’ (Bourdieu,

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

176 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

1984: 471). Doxa legitimates socially produced structural Bourdieu notes that the most obscure principle of

orders, and when objective and subjective orders are in action lies neither in structures nor in consciousness, but

equilibrium these result in the tacit, taken-for-granted of rather in ‘the relation of immediate proximity between

the social world (Berger and Luckmann, 1967) and in objective structures and embodied structures in habitus’

effect produce belief. Ultimately, objective structural (Bourdieu, 1996a: 38). Other authors have noted the

arrangements are arbitrary and doxa creates a reality based need to bring cognition into the sociological study of

on the socially forgotten imposition of hierarchies of culture and society (DiMaggio, 1997), but Bourdieu

value, or symbolic violence (Lizardo, 2009). These struc- understands cognition, in habitus, in a broader sense.

tures can come, however, out of phase; the existing order Habitus thus relates to the unconscious structure of fore-

can be transformed and questioned, and it is disjuncture sight and strategic sense making, which Chia (1994) notes

which may enable organizational foresight to arise. remains relatively unexplored.

Bourdieu (1996b) calls this the ‘space of possibles,’ and In the next section, we draw on recent conceptual and

this space presents itself as the relationship between sets empirical developments in entrepreneurship to illuminate

of dispositions and the structural chance of access to posi- how organizational foresight, legitimacy, and field dynam-

tions (Bourdieu, 1993: 64–65). The space of ‘possibles’ is ics can be understood through a Bourdieusian lens.

perceived through habitus, ‘which will, stimulated by this

perception, become able to occupy a position’ (Van Legitimacy and organizational foresight

Maanan, 2009: 71). Recent research in entrepreneurship has begun to explore

From a Bourdieusian perspective, foresight would not the notion of legitimacy using Bourdieu’s practice per-

represent metaphysical agency, but is ‘produced by the spective (De Clerq and Voronov, 2009a; Stringfellow

same system of embodied structures that would have et al., 2013). Theoretically, De Clerq and Voronov

resulted in unproblematic accommodation had the objec- (2009a–c) have developed the notion of legitimacy as an

tive structures remained in line with the subjective struc- enactment of entrepreneurial habitus, which enables a

tures’ (Lizardo, 2009: 27). Lizardo (2009) makes an theorization of the potentially contradictory nature of

insightful link between Bourdieu’s work and the little newcomers’ legitimacy. The contradiction arises from

recognized influence of the psychological genetic structur- newcomers’ need to balance the need to ‘fit in’ with the

alism of Jean Piaget on his theoretical framework. Habitus, institutional norms and taken-for-granted assumptions of

Lizardo (2009) points out, is seldom seen as a structure field incumbents (De Clerq and Voronov, 2009a) and the

but usually as a stand-in for individual or subjective con- need to ‘stand out’ as an entrepreneur. Fields are character-

sciousness, which is then faced with macro-level struc- ized by particular forms of capital, and they reproduce

tures. The Piagetian notion of a psychological (cognitive) dominant narratives of how new entrants should behave

structure (Piaget, 1970) allows: (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992), as well as specialized

and explicit knowledge and belief systems that are used as

. . . an appreciation of the sense in which the habitus evaluation criteria, requiring newcomers to fit in (Scott,

is a ‘structured structure’ and how the intersection of 1994). However, newcomers must also stand out, as aspir-

field and internalized dispositions in habitus is in fact ing entrepreneurs need to be perceived as challenging the

the meeting point of two ontologically distinct but dominant narrative of a field and bringing something new

mutually constitutive structural orders (objective and (De Clerq and Voronov, 2009a). The degree to which this

internalized) and not the point at which ‘agency’ meets is the case depends on the extent to which the new entrant

structure. (Lizardo, 2009: 10) is innovative versus imitative (Cliff et al., 2006), and the

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 177

relative balance will depend on the maturity of the field adapting to the changing environment and prevailing

(Stringfellow et al., 2013). trends from outside the professional field. In practice, this

De Clerq and Voronov (2009b) suggest that the rela- meant that the apostates would apply professional codes

tive benefit of institutional legitimacy, or fitting in, will of ethics more loosely, forging close relationships with

be high in mature fields. Building on this suggestion, their clients rather than maintaining their independence,

Stringfellow et al. (2013) present an empirical study using and being more openly orientated toward financial con-

Bourdieu’s practice theory to explore how legitimacy and cerns rather than client care (Stringfellow et al., 2013).

resource acquisition are constructed, relationally, by busi- Ultimately, compared with the ‘traditional’ profile, the

ness owners in a mature, institutionalized field. They apostates found it problematic to access resources such as

present a study of the owners of small accounting ventures information and new clients, suggesting they lacked legiti-

from which it emerges that two distinct groups of entre- macy in a mature field, where there is a doxic relation to

preneurs, with specific capital configurations, achieved the social world (Bourdieu, 1977). By contrast, the large

varying levels of success acquiring resources and legiti- accounting firms have been able to act as institutional

macy, which they term ‘traditional’ and ‘apostate.’ The entrepreneurs through boundary bridging and boundary

relationship of these groups to the dynamics of the field misalignment processes, implying that they are ‘immune

sheds light on how practice informs organizational fore- to coercive and normative processes because their market

sight, and how the success of foresight-based actions is activities expand beyond the jurisdiction of field-level

intimately linked to the institutional context. regulations’ (Greenwood and Suddaby, 2006: 27).

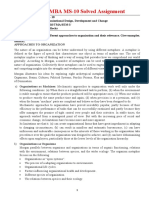

The ‘apostates’ in the study are those business owners Building on these insights, as well as the broader litera-

who have abandoned or renounced previously held beliefs tures of organizational foresight, entrepreneurial legitimacy,

or principles (the doxa) as to how a professional accoun- and Bourdieu’s practice theory, we have developed a model

tant should practice. This profile evaluated the future of how foresight emerges relative to the maturity of the

differently from the ‘traditional’ profile, and felt they were field and its legitimating characteristics. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Competing roles of doxa and foresight in mature and emerging fields.

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

178 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

In mature industries, habitus (which informs practice) By contrast, in emerging or transforming industries

tends to be aligned with the objective structure of the there is a lack of clearly defined templates, and organiza-

field, which is defined by a relatively stable social order tions need to legitimize new activity and establish patterns

and a collective memory that favors constancy and is of behavior (Déjean et al., 2004). Within such fields, it is

resistant to change (Bourdieu, 1990). Legitimacy in such more likely that a disjuncture between the subjective

fields is often based on cognitive and moral judgments of structure of habitus and the objective structures of the

the entity’s appropriateness to taken-for-granted norms, field will occur; or alternatively, the field is less rigidly

or doxa, associated with an institutional perspective of stratified and therefore the space of possibles opens up.

legitimacy. When there is alignment between the habitus This reflexive habitus can identify doxa, or taken-for-

and the field, or a strong hierarchical structure within granted structures and doctrines that were previously

the field, the ‘space of possibles’ will be limited and invisible and accepted subconsciously. Heterodox dis-

therefore habitus inclines toward orthodoxy rather than courses, such as those associated with organizational fore-

foresight. Dominant players who enjoy a position of sight, can therefore emerge which still relate to the past

seniority and power in the field use conservation strategies and present dynamics of the field, but which position the

aimed at defending their position and sustaining the doxic organization in accordance with anticipation of an alter-

social relations of the field (Swartz, 1997). In mature native future. In emerging fields, newcomers can use this

fields, the need to achieve institutional legitimacy tends foresight to generate strategies of succession aimed at

to limit the potential for creativity and foresightful prac- achieving dominance, whilst balancing the dual require-

tices, unless an exogenous shock, or the relationship ments of ‘fitting in’ and ‘standing out’ (De Clerq and

of organizations to the field, changes in such a way that Voronov, 2009a). Alternatively, iconoclasts, who tend to

the field itself is transformed, for example through insti- pursue strategies of subversion — which is a more radical

tutional entrepreneurship (Greenwood and Suddaby, attempt to break free from the dominant group by dis-

2006). crediting the status quo and legitimating its logics and

Newcomers entering a mature field will tend to pursue practices, that is acting as institutional entrepreneurs

strategies of succession aimed at gaining access to domi- (David et al., 2013) — may also channel organizational

nant positions in the field, but these will tend to be con- foresight. Owing to the disjuncture of habitus from the

sistent with ‘fitting in’ and adopting existing cognitive institutionalized norms of the field, foresight tends to be

norms, models, scripts, and patterns of behavior (De associated with strategic and pragmatic legitimacy, which

Clerq and Voronov, 2009b; Stringfellow et al., 2013; is directed toward self-interested actions.

Zimmerman and Zeitz, 2002). The collective memory

structures of habitus place boundaries around cognition,

creating the problem of reclusiveness ‘as illustrated in path Discussion and conclusion

dependence, persistent organizational routines, and orga- The practice of entrepreneurship is itself intertwined with

nizational memory’ ( Jarzabkowski, 2004: 533). Icono- legitimacy and organizational foresight, the navigation of

clasts or rule breakers in mature industries will lack dynamic tensions that exist between everyday structures

institutional legitimacy, and are likely to be punished as and sense making of those structures, and ‘the continuous

deviants, as was found with the apostates in the Stringfel- evaluation of different organisational futures’ (Fuller and

low et al. (2013) study. It is therefore less likely (although Warren, 2006). Here, we have used Bourdieu’s theory of

not impossible) that organizational foresight will emerge practice to explore how organizational foresight may

in mature, institutionalized contexts. emerge, and how it relates to the underlying legitimating

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 179

dynamics of the field. Foresight can emerge when there is neurs (Greenwood and Suddaby, 2006). The struggle for

a disjuncture between the objective structures of the field legitimacy goes hand in hand with the struggle between

and the subjective structures of the habitus, since: ‘At positions and the agents who occupy them; and ‘in the

crucial points of disjuncture, dislocation invites distance phase of equilibrium, the space of positions tends to

taking, reappraisal and the development of fresh under- govern the space of positions-takings’ (Bourdieu, 1996b:

standings (Heidegger, 1962), which can be further refined 231). In a weakly institutionalized field:

in light of experience and rendered dispositional’ (Maclean

et al., 2012b: 400). This means that social structures, . . . agents always have an objective margin of

which normally function below the level of consciousness freedom at their disposal (which they can yes or no

and discourse, become apparent (Bourdieu, 1984). This make use of, dependent on their ‘subjective’

disjuncture may result from the unbalanced relationship dispositions), no matter how tight the requirements

between an agent’s habitus and her position, because of included in their position may be. (Bourdieu,

field-level transformations such as crisis, social and cul- 1993: 65)

tural change, or because the field itself is young and in

flux. The resulting reflexive mode of habitus can identify Radical changes in the structure of positions can only

doxa, with the potential to generate instead heterodox, happen under two conditions: if innovations are already

foresightful strategies. present in the field and they can be accepted by at least a

The objective structure of the field will condition the small number of people; or if support can be found in

style of these strategies and their respective chances of external forces (Bourdieu, 1996b). The model of legiti-

success. Dominant incumbents in mature fields will macy and foresight that we have presented here does not

usually generate conservative strategies that defend ortho- preclude the possibility of foresight emerging in mature

doxy or the prevailing discourse. Newcomers to mature fields, but rather suggests that the doxic relation to the

fields are likely to pursue succession strategies that are social world in such fields means there is less likely to be

aimed at ‘fitting in’ and gaining access to dominant posi- a disjuncture between habitus and the objective structures

tions. By contrast, newcomers in emerging or transform- of the field. Such fields are highly stratified, with stable,

ing fields will use organizational foresight to generate routinized interactions between embedded members that

succession strategies that allow them to both fit in and may limit organizational foresight, due to the taken-for-

stand out. Iconoclasts are more peripheral to the domi- grandness of institutionalized, embedded practice. The

nant group, and generate heterodox discourses aimed at ‘space of possibles’ is more restricted, but this may be

subversion, which ultimately may result in new organiza- disturbed by environmental factors such as ‘social

tional forms and institutional entrepreneurship. There is upheaval, technological disruptions, competitive discon-

a greater potential to create strategic legitimacy in new or tinuities and regulatory change’ (Greenwood and Suddaby,

transforming fields, and organizational foresight is more 2006: 28), which precipitate either the need for foresight,

likely to flourish without the constraints of a high degree or the entry of new players into the organizational field.

of institutionalization. The core contributions of this paper lie in conceptual-

Although there is always an opportunity to play the izing why organizational foresight may or may not emerge

game in more than one way, in mature, institutionalized in different institutional contexts and in theorizing the

fields it is unlikely that iconoclasts who go against the consequences of foresight in relation to organizations

field’s doxa will be perceived as legitimate, unless they achieving either institutional or strategic legitimacy. Our

possess sufficient resources to act as institutional entrepre- model illustrates a Bourdieusian practice perspective of

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

180 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

foresight that accommodates the structure of the field, Bourdieu P. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. Essays on Art

which determines possibilities, with the subjective rela- and Literature. Polity Press: Cambridge.

tionship of habitus to the field that generates the invisible Bourdieu P. 1996a. The State Nobility. Translated by Lauretta

cognitive structures central to organizational foresight. As C. Clough. Polity Press: Cambridge.

with all research, we acknowledge that this paper has Bourdieu P. 1996b. The Rules of Art, Genesis and Structure

limitations, particularly (given spatial constraints), the of the Literary Field. Stanford University Press: Cornwall,

lack of empirical data to support our conclusions (see, CA.

however, Stringfellow et al., 2013). Nevertheless, we hope

Bourdieu P, Wacquant L. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociol-

the model of foresight and legitimacy developed here can ogy. Chicago University Press: Chicago.

serve as a basis for future research that takes a practice

Bourgeois L, Eisenhardt K. 1988. Strategic decision processes

perspective of foresight as an inherently social process.

in high velocity environments: Four cases in the microcom-

Given that we created our model largely based on

puter industry. Management Science 34: 816–835.

Bourdieu’s writing, in conjunction with empirical findings

Chia R. 1994. The concept of decision: A deconstructive analy-

in a mature field, it would be interesting to examine its

sis. Journal of Management Studies 31: 781–806.

appropriateness in young, emerging, or high-velocity

fields (cf. Sarpong, 2011; Sarpong and Maclean, 2011, Chia R. 2004a. The shaping of dominant modes of thought.

2012). Future studies could also examine dominant, new- Rediscovering the foundations of management knowledge. In

Jeffcut P (ed.), The Foundations of Management Knowledge.

comer, and iconoclast groups to test if and how organiza-

Routledge: London, pp. 169–187.

tional foresight relates to the strategies of conservation,

succession, and subversion outlined in our model. Chia R. 2004b. Re-educating attention: What is foresight and

how is it cultivated? In Tsoukas H, Shepherd J (eds), Managing

References the Future: Foresight in the Knowledge Economy. Blackwell:

Oxford, pp. 21–37.

Andriopoulos C, Gotsi M. 2006. Probing the future: Mobilis-

ing foresight in multiple-product innovation firms. Futures Chia R. 2004c. Strategy-as-practice: Reflections on the research

38(1): 50–66. agenda. European Management Review 1(1): 29–34.

Anheier H, Gerhards J, Romo F. 1995. Forms of capital and Chia R. 2008. Enhancing entrepreneurial learning through

social structure in cultural fields: Examining Bourdieu’s social peripheral vision. In Harrison R, Leitch C (eds), Entrepreneur-

topography. American Journal of Sociology 100(4): 859–903. ial Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Applications. Rout-

ledge: London, pp. 27–43.

Berger P, Luckman T. 1967. The Social Construction of Reality:

A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Penguin Books: Cliff J, Jennings D, Greenwood R. 2006. New to the game and

Harmondsworth. questioning the rules: The experiences and beliefs of founders

Bourdieu P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge who start imitative vs. innovative firms. Journal of Business

University Press: Cambridge. Venturing 21(5): 633–663.

Bourdieu P. 1984. Distinction. Translated by Richard Nice. Constanzo LA. 2004. Strategic foresight in a high-speed envi-

Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA. ronment. Futures 36(2): 219–235.

Bourdieu P. 1986. The forms of social capital. In Richardson J Constanzo L, MacKay RB (eds). 2009. Handbook of Research

(ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of on Strategy and Foresight. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham.

Education. Greenwood: New York.

Cunha M. 2004. Time traveling: Organizational foresight as

Bourdieu P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Polity Press: temporal reflexivity. In Tsoukas H, Shepherd J (eds), Manag-

Cambridge. ing the Future. Blackwell: Oxford.

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 181

Das T, Teng B. 1999. Cognitive biases and strategic decision- Fontela E, Guzmán J, Pérez M, Santos F. 2006. The art of

making: An integrating perspective. Journal of Management entrepreneurial foresight. Foresight 8(6): 3–13.

Studies 36(6): 757–778.

Fuller T, Warren L. 2006. Entrepreneurship as foresight: A

David R, Sine W, Haveman H. 2013. Seizing opportunities in complex social network perspective on organisational fore-

emerging fields: How institutional entrepreneurs legitimated sight. Futures 38(8): 956–971.

the professional form of management consultancy. Organiza-

Fuller T, Warren L, Argyle P. 2008. Sustaining entrepreneurial

tion Science 24(2): 356–377.

business: A complexity perspective on processes that produce

De Clerq D, Voronov M. 2009a. Toward a practice perspective: emergent practice. International Entrepreneurship and Manage-

Entrepreneurial legitimacy as habitus. International Small ment Journal 4(1): 1–17.

Business Journal 27(4): 395–419.

Garud R, Hardy C, Maguire C. 2007 Institutional entrepre-

De Clerq D, Voronov M. 2009b. The role of domination in neurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special

newcomers’ legitimation as entrepreneurs. Organization 16(6): issue. Organization Studies 28(7): 957–969.

799–827.

Greenwood R, Suddaby R. 2006. Institutional entrepreneur-

De Clerq D, Voronov M. 2009c. The role of cultural and sym- ship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy

bolic capital in entrepreneurial capability to meet expectations of Management Journal 49(1): 27–48.

about conformity and innovation. Journal of Small Business

Management 47(3): 398–420. Heidegger M. 1962. Being and Time. Harper & Row: New

York, NY.

Déjean F, Gond J, Leca B. 2004. Measuring the unmeasured:

An institutional entrepreneur strategy in an emerging indus- Holt D. 1998. Does cultural capital structure American con-

try. Human Relations 57: 741–764. sumption? Journal of Consumer Research 25(1): 1–25.

Dewald J, Bowen F. 2010. Storm clouds and silver linings: Jarzabkowski P. 2004. Strategy as practice: Recursiveness,

Responding to disruptive innovations through cognitive resil- adaption, and practices-in-use. Organization Studies 25(4):

ience. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 34(1): 197–218. 529–560.

DiMaggio P. 1997. Culture and cognition. Annual Review of King A. 2000. Thinking with Bourdieu against Bourdieu: A

Sociology 23: 263–287. ‘practical’ critique of the habitus. Sociological Theory 18:

417–433.

DiMaggio P, Powell W. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Insti-

tutional isomorphism and collective rationality in orga- Kostova T, Zaheer S. 1999. Organizational legitimacy under

nizational fields. American Sociological Review 48(April): conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enter-

147–160. prise. Academy of Management Review 24(1): 64–81.

Dobbin F. 2008. The poverty of organizational theory: Lizardo O. 2009. The cognitive origins of Bourdieu’s habitus.

Comment on ‘Bourdieu and organizational analysis.’ Theory Available at https://www3.nd.edu/~olizardo/papers/jtsb

and Society 37(1): 53–63. -habitus.pdf.

Drori I, Honig B, Sheaffer Z. 2009. The life cycle of an internet Lounsbury M, Glynn M. 2001. Cultural entrepreneurship:

firm: Scripts, legitimacy, and identity. Entrepreneurship Theory Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic

& Practice 33(3): 715–738. Management Journal 22: 545–564.

Emirbayer M, Mische A. 1998. What is agency? American Loveridge D. 2008. Foresight: The Art and Science of Anticipating

Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023. the Future. Routledge: New York.

Fararo T, Butts C. 1999. Advances in generative structuralism: Maclean M, Harvey C, Chia R. 2012a. Sensemaking, storytell-

Structured agency and multilevel dynamics. The Journal of ing and the legitimization of elite business careers. Human

Mathematical Sociology 24: 1–65. Relations 65(1): 17–40.

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

182 Lindsay Stringfellow and Mairi Maclean

Maclean M, Harvey C, Chia R. 2012b. Reflexive practice and Sarpong D, Maclean M. 2012. Mobilizing differential visions

the making of elite business careers. Management Learning for new product innovation. Technovation 32(12): 694–702.

43(4): 385–404.

Scott W. 1994. Institutions and organizations: Toward a theo-

Maguire S, Hardy C, Lawrence T. 2004. Institutional entrepre- retical synthesis. In Scott W, Meyer J (eds), Institutional Envi-

neurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy ronments and Organizations. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.

in Canada. Academy of Management Journal 47: 657–679. 55–80.

Malsch B, Gendron Y, Grazzini F. 2011. Investigating interdis- Scott W, Meyer J. 1991. The organization of societal sectors. In

ciplinary translations: The influence of Pierre Bourdieu on Powell W, DiMaggio P (eds), The New Institutionalism in

accounting literature. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Organizational Analysis. University of Chicago Press: Chicago,

Journal 24(2): 194–228. pp. 390–422.

Neustadt R, May E. 1986. Thinking in Time: The Use of History Shane S, Venkataraman S. 2000. The promise of entrepreneur-

for Decision Makers. Free Press: New York. ship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review

Nicholls A. 2010. The legitimacy of social entrepreneurship: 26(1): 217–226.

Reflexive isomorphism in a pre-paradigmatic field. Entrepre- Smith D, Lohrke F. 2008. Entrepreneurial network develop-

neurship Theory and Practice 34(4): 611–633. ment: Trusting in the process. Journal of Business Research

Oliver C. 1991. Strategic responses to institutional processes. 61(4): 315–322.

Academy of Management Review 16(1): 145–179. Stringfellow L, Shaw E, Maclean M. 2013. Apostasy versus

Oliver C. 1996. The institutional embeddedness of economic legitimacy: Relational dynamics and routes to resource

activity. Advances in Strategic Management 13: 163–186. acquisition in entrepreneurial ventures. International Small

Business Journal, January 13, 2013. DOI: 10.1177/02662426

Ozbilgin M, Tatli A. 2005. Understanding Bourdieu’s contribu- 12471693.

tion to organization and management studies. Academy of

Management Review 30(4): 855–869. Suchman M. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institu-

tional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20:

Packalen K. 2007. Complementing capital: The role of status, 571–610.

demographic features, and social capital in founding teams’

ability to obtain resources. Entrepreneurship Theory and Prac- Suddaby R, Greenwood R. 2005. Rhetorical strategies of legiti-

tice 31(6): 873–891. macy. Administrative Science Quarterly 50: 35–67.

Palazzo G, Scherer A. 2006. Corporate legitimacy as delibera- Swartz D. 1997. Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre

tion: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics Bourdieu. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

66: 71–88. Tornikoski E, Newbert S. 2007. Exploring the determinants of

Pfeffer J. 1981. Management as symbolic action: The creation organizational emergence: A legitimacy perspective. Journal of

and maintenance of organizational paradigms. In Cummings Business Venturing 22: 311–335.

L, Staw B (eds), Research in Organizational Behavior. JAI Press:

Tsoukas H, Chia R. 2002. On organizational becoming:

Greenwich, CT, pp. 1–52.

Rethinking organizational change. Organization Science 13(5):

Piaget J. 1970. Structuralism. Basic Books: New York. 567–582.

Sarpong D. 2011. Towards a methodological approach: Theo- Tsoukas H, Shepherd J. 2004a. Organization and the future. In

rising scenario thinking as a social practice. Foresight 13(2): Tsoukas H, Shepherd J (eds), Managing the Future: Foresight

4–17. in the Knowledge Economy. Blackwell: Oxford.

Sarpong D, Maclean M. 2011. Scenario thinking: A practice Tsoukas H, Shepherd J. 2004b. Coping with the future:

based approach to the identification of opportunities for inno- Developing organizational foresightfulness. Futures 36(2):

vation. Futures 43(10): 1154–1163. 137–144.

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

‘Space of Possibles’? 183

Van Maanan H. 2009. How to Study Art Worlds. Amsterdam Whitehead A. 1933. Adventures of Ideas. Macmillan: New York.

University Press: Amsterdam.

Zimmerman M, Zeitz G. 2002. Beyond survival: Achieving

Weick KE. 2001. Making Sense of the Organization. Blackwell: new venture growth by building legitimacy. Academy of Man-

Malden, MA. agement Review 27(3): 414–431.

Welter F. 2011. Contextualizing entrepreneurship — concep- Zott C, Huy Q. 2007. How entrepreneurs use symbolic man-

tual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and agement to acquire resources. Administrative Science Quarterly

Practice 35(1): 165–184. 52(1): 70–105.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Lindsay Stringfellow is a Senior Lecturer in the Mairi Maclean is Professor of International

Department of Organisation Studies at the Management and Organisation Studies at the

University of Exeter Business School. Her research University of Exeter Business School. Her research

interests are related to issues of legitimacy, interests include international business elites and

particularly in the traditional professions, and elite power, especially from a Bourdieusian

exploring broad issues of structure, agency, and perspective, entrepreneurial philanthropy, history,

power conceived of within the theoretical domain of and organization studies.

scholars such as Bourdieu.

Correspondence to:

Lindsay Stringfellow

University of Exeter Business School

Rennes Drive

Exeter EX4 4PU, UK

e-mail: l.j.stringfellow@exeter.ac.uk

Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Strategic Change

DOI: 10.1002/jsc

Copyright of Strategic Change is the property of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and its content may

not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's

express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for

individual use.

You might also like

- Training For Wisdom With The Illeist Diary MethodDocument25 pagesTraining For Wisdom With The Illeist Diary MethodMike McDNo ratings yet

- 4 Key Aspects To VariographyDocument14 pages4 Key Aspects To Variographysupri100% (2)

- Morse 101.v2PDocument75 pagesMorse 101.v2PNL100% (2)

- Pol-Gov: Lesson 1Document29 pagesPol-Gov: Lesson 1Romilyn Mangaron PelagioNo ratings yet

- Organization and ManagementDocument34 pagesOrganization and ManagementCpdo Bago86% (7)

- Managing ExpectationsDocument24 pagesManaging ExpectationsSandesh KesarkarNo ratings yet

- Corporate Foresight and Its Effect On Innovation, Strategic Decision Making and Organizational Performance - BankingDocument18 pagesCorporate Foresight and Its Effect On Innovation, Strategic Decision Making and Organizational Performance - BankingAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Towards A Critical Theory of Spirit: The Insistent Demands of Erna Brodber's MyalDocument12 pagesTowards A Critical Theory of Spirit: The Insistent Demands of Erna Brodber's MyalDaniel EspinosaNo ratings yet

- BUSM4403 Assignment 1Document5 pagesBUSM4403 Assignment 1Thao LuongNo ratings yet

- 03 - Donaldson 2001 Contingency Theory Cap.1Document17 pages03 - Donaldson 2001 Contingency Theory Cap.1FabianoNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Reading SkillsDocument23 pagesFundamental Reading SkillsMary Joy DailoNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Lab1 PDF - 06-13Document11 pagesChemistry Lab1 PDF - 06-13cagdianad Dj100% (2)

- The Composition of Electroacoustic Music: by Rodolfo CaesarDocument72 pagesThe Composition of Electroacoustic Music: by Rodolfo CaesarDaríoNowakNo ratings yet

- Barley y Tolbert InstitutionalizationDocument25 pagesBarley y Tolbert InstitutionalizationNanNo ratings yet

- 1.3. Kenneth BensonDocument22 pages1.3. Kenneth BensonLuis Alberto Rocha MartinezNo ratings yet

- 2017 Berthod BC Instit TheoryDocument5 pages2017 Berthod BC Instit TheoryJasmina MilojevicNo ratings yet

- Ethichs and Corporate CultureDocument18 pagesEthichs and Corporate CultureShamlee RamtekeNo ratings yet

- The Political Cybernetics of Organ IsationsDocument30 pagesThe Political Cybernetics of Organ IsationsmyollesNo ratings yet

- For All Types of Assignments and Research Writing HelpDocument21 pagesFor All Types of Assignments and Research Writing HelpStena NadishaniNo ratings yet

- From Ritual To Reality: Demography, Ideology, and Decoupling in A Post-Communist Government AgencyDocument25 pagesFrom Ritual To Reality: Demography, Ideology, and Decoupling in A Post-Communist Government AgencyAnonymous KJBbPI0xeNo ratings yet

- Nonaka DynamicTheoryOrganizational 1994Document25 pagesNonaka DynamicTheoryOrganizational 1994Milin Rakesh PrasadNo ratings yet

- Ranson StructuringOrganizationalStructures 1980Document18 pagesRanson StructuringOrganizationalStructures 1980Hay LinNo ratings yet

- Understanding Institutions: Different Paradigms, Different ConclusionsDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Institutions: Different Paradigms, Different ConclusionsJAN STIVEN ASUNCIÓN FLORESNo ratings yet

- Organizational InnovationDocument33 pagesOrganizational InnovationKalakriti IITINo ratings yet

- Organizational RolesDocument18 pagesOrganizational RolesFabiano Pires de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Internasional Chapter Basic Organizational DesignDocument12 pagesJurnal Internasional Chapter Basic Organizational DesignMc KeteqmanNo ratings yet

- Aula 5 - Maguire Institutional EntrepreneurshipDocument13 pagesAula 5 - Maguire Institutional EntrepreneurshipferreiraccarolinaNo ratings yet

- IGNOU MBA MS-10 SolvedDocument15 pagesIGNOU MBA MS-10 SolvedtobinsNo ratings yet

- Greenwood e Suddaby (2006) - Institutional Entrepreneurship in Mature FieldsDocument23 pagesGreenwood e Suddaby (2006) - Institutional Entrepreneurship in Mature FieldsVinciusNo ratings yet

- Toward A Diagnostic Tool For Organizational Ethical Culture With Futures Thinking and Scenario PlanningDocument13 pagesToward A Diagnostic Tool For Organizational Ethical Culture With Futures Thinking and Scenario PlanningbinabazighNo ratings yet

- Documento 1Document27 pagesDocumento 1Santiago Espitia TorresNo ratings yet

- Beyond Constraint - How Institutions Enable IdentitiesDocument33 pagesBeyond Constraint - How Institutions Enable IdentitiesCamilo Adrián Frías Tilton100% (1)

- Career Development Insight From Organisation TheoryDocument15 pagesCareer Development Insight From Organisation TheoryRenata gomes de jesusNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 1047831095900063 MainDocument22 pages1 s2.0 1047831095900063 MainRendy GunawanNo ratings yet

- J Management Studies - 2004 - Wright - Resourceful Sensemaking in An Administrative GroupDocument21 pagesJ Management Studies - 2004 - Wright - Resourceful Sensemaking in An Administrative GroupMelita Balas RantNo ratings yet

- Presentation Final MT&a.Document24 pagesPresentation Final MT&a.zain.naqviNo ratings yet

- Orlikowski, W. (1996) Improvising Organizational Change Over TimeDocument31 pagesOrlikowski, W. (1996) Improvising Organizational Change Over TimeDon McNishNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0048733313000450 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0048733313000450 MainlolNo ratings yet

- ML - Notes Barley and Tolbert (1997)Document5 pagesML - Notes Barley and Tolbert (1997)luisNo ratings yet

- Thorton e Ocasio (2008) - Institutional LogicsDocument31 pagesThorton e Ocasio (2008) - Institutional LogicsVinciusNo ratings yet

- Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University, Sage Publications, Inc. Administrative Science QuarterlyDocument26 pagesJohnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University, Sage Publications, Inc. Administrative Science QuarterlySabin ShresthaNo ratings yet

- St4S39-V1 Systems Thinking Assessment Essay 1: by Joseph Wabwire (Id Number: 74108522/)Document19 pagesSt4S39-V1 Systems Thinking Assessment Essay 1: by Joseph Wabwire (Id Number: 74108522/)Joseph Arthur100% (7)

- Macro Environment and Organisational Structure A ReviewDocument9 pagesMacro Environment and Organisational Structure A ReviewEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Danielson 2004Document31 pagesDanielson 2004AzmatIslamNo ratings yet

- R I I ? K M S: Ational or Nstitutional Ntent Nowledge Anagement Adoption in Audi Public OrganizationsDocument23 pagesR I I ? K M S: Ational or Nstitutional Ntent Nowledge Anagement Adoption in Audi Public OrganizationsHani BerryNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Institutional Theory and Contingency TheoryDocument4 pagesA Comparison of Institutional Theory and Contingency TheoryrajiragaNo ratings yet

- Creati ChaosDocument6 pagesCreati Chaosyoxik31823No ratings yet

- Management For Engineers Part4Document25 pagesManagement For Engineers Part4Aswin SNo ratings yet

- Sociomaterial Practices: Exploring Technology at Work: EssaiDocument14 pagesSociomaterial Practices: Exploring Technology at Work: Essaiyz2104382No ratings yet

- Unit 2 Organisational Processes: ObjectivesDocument14 pagesUnit 2 Organisational Processes: ObjectivesJaya AravindNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Organisational BehaviourDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Organisational Behaviourakshatjha089No ratings yet

- IGNOU MBA MS-10 Solved Assignment 2013Document17 pagesIGNOU MBA MS-10 Solved Assignment 2013mukulNo ratings yet

- Symposium: Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and FutureDocument15 pagesSymposium: Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and FutureIsmail JamesNo ratings yet

- Article Reviewed By:: Tollera SisayDocument3 pagesArticle Reviewed By:: Tollera SisayTatekia DanielNo ratings yet

- Top 10 IS Theories 2014 PDFDocument24 pagesTop 10 IS Theories 2014 PDFimzoo_wickedNo ratings yet

- Institutional LogicsDocument32 pagesInstitutional LogicsКсюня БогдановнаNo ratings yet

- Chung 2015Document9 pagesChung 2015Mutia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- NONAKASesion 4Document9 pagesNONAKASesion 4leonav22No ratings yet

- Powell Bromley EncyclopediaDocument13 pagesPowell Bromley EncyclopediaEnes KılıçNo ratings yet

- 32 QuestionsDocument14 pages32 Questionsfabar21399No ratings yet

- Centralization 2Document14 pagesCentralization 2Qasim ButtNo ratings yet

- PPM EN 2005 03 JanczakDocument14 pagesPPM EN 2005 03 JanczakTeddy jeremyNo ratings yet

- Module in Discipline and Ideas in Social Sciences: Performance StandardsDocument13 pagesModule in Discipline and Ideas in Social Sciences: Performance StandardsJervis HularNo ratings yet

- Scott 1987 The Adolescence of Institutional TheoryDocument20 pagesScott 1987 The Adolescence of Institutional TheorywalterNo ratings yet

- A Review On Effect of Culture, Structure, Technology and Behavior On OrganizationsDocument8 pagesA Review On Effect of Culture, Structure, Technology and Behavior On Organizationsyoga sugiastikaNo ratings yet

- PA 301 Institutional TheoryDocument42 pagesPA 301 Institutional Theorytom villarinNo ratings yet

- Designing Organizations Does Expertise MatterDocument16 pagesDesigning Organizations Does Expertise MattervafegarNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Field of Organizational BehaviourDocument32 pagesIntroduction To The Field of Organizational BehaviourSubharaman VenkitaNo ratings yet

- Scenario Thinking: Preparing Your Organization for the Future in an Unpredictable WorldFrom EverandScenario Thinking: Preparing Your Organization for the Future in an Unpredictable WorldNo ratings yet

- R&D Intensity and Corporate Foresight - Their Relationship and Joint Impact On Firm PerformanceDocument16 pagesR&D Intensity and Corporate Foresight - Their Relationship and Joint Impact On Firm PerformanceAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Association Between Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performanceevaluating - The - Association - BetDocument11 pagesEvaluating The Association Between Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performanceevaluating - The - Association - BetAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Corporate Foresight in Multinational Business StrategiesDocument15 pagesCorporate Foresight in Multinational Business StrategiesAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Making Use of Corporate Foresight - Lessons Learnt From Industrial PractiseDocument13 pagesMaking Use of Corporate Foresight - Lessons Learnt From Industrial PractiseAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Designing Foresight and Foresighting Design Opportunities For Learning and Collaboration Via ScenariosDocument13 pagesDesigning Foresight and Foresighting Design Opportunities For Learning and Collaboration Via ScenariosAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- The Ideomotor Recycling Theory For Tool Use, Language, and ForesightDocument14 pagesThe Ideomotor Recycling Theory For Tool Use, Language, and ForesightAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- A Theoretical Model For Networked ForesightDocument16 pagesA Theoretical Model For Networked ForesightAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Aspects of Corporate ForesightDocument14 pagesThe Psychological Aspects of Corporate ForesightAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Corporate Foresight: The Alien Nature of Business Visioning and Pre-Emptive ActionDocument3 pagesCorporate Foresight: The Alien Nature of Business Visioning and Pre-Emptive ActionAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Introducing The Competitive Dimension To Corporate ForesightDocument10 pagesIntroducing The Competitive Dimension To Corporate ForesightAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- A Policy Agenda To Develop Human Capital For The Modern EconomyDocument24 pagesA Policy Agenda To Develop Human Capital For The Modern EconomyAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Multiplication of Negative ScenariosDocument17 pagesMultiplication of Negative ScenariosAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Contemporary Latin America Through The Hypotheses of Institutional Political EconomyDocument41 pagesInterpreting Contemporary Latin America Through The Hypotheses of Institutional Political EconomyAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- ICT-Tools in Foresight - A DelDocument11 pagesICT-Tools in Foresight - A DelAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Explicating The Future of Work - Perspectives From IndiaDocument20 pagesExplicating The Future of Work - Perspectives From IndiaAladdin Prince100% (1)

- The Changing Nature of WorkDocument18 pagesThe Changing Nature of WorkAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Modern Globalization Processes On Innovative Development of Labor PotentialDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Modern Globalization Processes On Innovative Development of Labor PotentialAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Moment of InertiaDocument13 pagesMoment of InertiaAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Adult Learning, Economic Growth and The Distribution of IncomeDocument13 pagesAdult Learning, Economic Growth and The Distribution of IncomeAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Effect of Informal Training On Skill Levels of Manufacturing WorkersDocument15 pagesEffect of Informal Training On Skill Levels of Manufacturing WorkersAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- A Changing Labour Market - Economic Recovery and JobsDocument13 pagesA Changing Labour Market - Economic Recovery and JobsAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- The Determinants of Lifelong LearningDocument13 pagesThe Determinants of Lifelong LearningAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Moment of InertiaDocument13 pagesMoment of InertiaAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Icom IC-746 Pro Instruction ManualDocument116 pagesIcom IC-746 Pro Instruction ManualYayok S. AnggoroNo ratings yet

- Moment of InertiaDocument13 pagesMoment of InertiaAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- UN Well Being of NationsDocument121 pagesUN Well Being of NationsAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Higher Education in 2040 A GlobalDocument159 pagesReflections On Higher Education in 2040 A GlobalAladdin PrinceNo ratings yet

- Hendrick 1986Document11 pagesHendrick 1986pmbhatNo ratings yet

- Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning DomainsDocument10 pagesBloom's Taxonomy of Learning DomainsMa. Rhodora MalicdemNo ratings yet

- On Sequential AnalysisDocument9 pagesOn Sequential Analysisyashi0% (1)

- Preference and ChoiceDocument29 pagesPreference and ChoiceShanuNo ratings yet

- HALLIDAY'S Systemic Functional GrammarDocument14 pagesHALLIDAY'S Systemic Functional GrammarPinky Mariel MangayaNo ratings yet

- Dean Radin Et Al - Assessing The Evidence For Mind-Matter Interaction EffectsDocument14 pagesDean Radin Et Al - Assessing The Evidence For Mind-Matter Interaction EffectsHtemaeNo ratings yet

- Chisquare Indep Sol1Document13 pagesChisquare Indep Sol1Munawar100% (1)

- An Analysis of Accuracy Level of Google Translate (Fix Thesis)Document5 pagesAn Analysis of Accuracy Level of Google Translate (Fix Thesis)NisrinadifNo ratings yet

- Quality Manual: Pylon Electronics IncDocument47 pagesQuality Manual: Pylon Electronics Incpaeg6512No ratings yet

- Theories and Principles of Health EthicsDocument21 pagesTheories and Principles of Health EthicsIris MambuayNo ratings yet

- Two Tail Tests:: Accept The Null HypothesisDocument8 pagesTwo Tail Tests:: Accept The Null HypothesisAneelaMalikNo ratings yet

- Preponderance of Evidence.: Explanation: Most of The States in America Use Clear and Convincing Evidence For DisbarmentDocument11 pagesPreponderance of Evidence.: Explanation: Most of The States in America Use Clear and Convincing Evidence For DisbarmentRia Evita RevitaNo ratings yet

- A Multidimensional Physical Self-Concept and Its Relations To Multiple Components of Physical FitnessDocument13 pagesA Multidimensional Physical Self-Concept and Its Relations To Multiple Components of Physical FitnessEva DepalogNo ratings yet

- CJ NEWTON - Idealism As An Educational Philosophy - An Analysis - May 2011Document10 pagesCJ NEWTON - Idealism As An Educational Philosophy - An Analysis - May 2011Chris Ackee B NewtonNo ratings yet

- Stability Studies and Estimating Shelf Life With Regression ModelsDocument1 pageStability Studies and Estimating Shelf Life With Regression ModelsYourOwn60No ratings yet

- 2.1. Methodological Directions in Translation StudiesDocument12 pages2.1. Methodological Directions in Translation StudiesYousef Ramzi TahaNo ratings yet

- Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods R PDFDocument1 pageDesigning and Conducting Mixed Methods R PDFjonephNo ratings yet

- CH 1 Fundamentals of Expert SystemsDocument48 pagesCH 1 Fundamentals of Expert SystemsSerak ShiferawNo ratings yet

- Tugas Sintesis 30 ArtikelDocument22 pagesTugas Sintesis 30 ArtikelErnita AprianiNo ratings yet

- Analysis For Business Chi-Square TestDocument28 pagesAnalysis For Business Chi-Square TestthamiradNo ratings yet

- IGNOU - B.Sc. - MTE09: Real AnalysisDocument327 pagesIGNOU - B.Sc. - MTE09: Real Analysisephunt100% (1)

- Group 6 - Paper N3Document7 pagesGroup 6 - Paper N3Denis Omar Huaman YactayoNo ratings yet