Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Measuring Costs and Outcomes of Tele-Intervention When Serving Families of Children Who Are Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing

Uploaded by

anaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring Costs and Outcomes of Tele-Intervention When Serving Families of Children Who Are Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing

Uploaded by

anaCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.

edu

Measuring Costs and Outcomes

of Tele-Intervention When Serving Families

of Children who are Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing

Kristina M. Blaiser, PhD, CCC-SLP,1 Diane Behl, MEd,2

Catherine Callow-Heusser, PhD,2 K arl R. White, PhD2

1

Department of Communicative Disorders and Deaf Education, College of Education

and Human Services, Utah State University, Logan, UT

2

National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management, Utah State University,

Logan, UT

Abstr act

Background: Optimal outcomes for children who are deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH) depend on access to high quality,

specialized early intervention services. Tele-intervention (TI), the delivery of early intervention services via telehealth

technology, has the potential to meet this need in a cost-effective manner.

Method: Twenty-seven families of infants and toddlers with varying degrees of hearing loss participated in a randomized

study, receiving their services primarily through TI or via traditional in-person home visits. Pre- and post-test measures of

child outcomes, family and provider satisfaction, and costs were collected.

Results: The TI group scored statistically significantly higher on the expressive language measure than the in-person

group (p =.03). A measure of home visit quality revealed that the TI group scored statistically significantly better on the

Parent Engagement subscale of the Home Visit Rating Scales-Adapted & Extended (HOVRS-A+; Roggman et al., 2012).

Cost savings associated with providing services via TI increased as the intensity of service delivery increased. Although

most providers and families were positive about TI, there was great variability in their perceptions.

Conclusions: Tele-intervention is a promising cost-effective method for delivering high quality early intervention services

to families of children who are DHH.

Keywords: Deaf/hard-of-hearing, tele-intervention, early intervention

Approximately 3 children per 1,000 are born with (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2013).

permanent hearing loss, making this the most frequent In fact, a letter to all early intervention state programs

congenital condition in the United States (White, 2007). from the US Departments of Education and Health and

When not detected and treated early, children who Human Services noted a “growing national crisis in the

are deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH) experience speech provision of essential early intervention and health care

and language delays that contribute to problems with services for infants and toddlers with hearing loss” (Hager

cognitive, language, academic, and social development & Giannini, personal communication, July 21, 2006). The

(White, Forsman, Eichwald, & Muñoz , 2010). Twenty primary reasons such inadequate services occur include

years ago, children born with hearing loss were typically the following (CDC, 2013; White, 2007):

not identified until they were 2 to 3 years old (Towards • There is a severe shortage of professionals who are

Equality, 1988; White, 2007). Today universal newborn trained and knowledgeable about current methods for

hearing screening, coupled with advances in hearing effectively educating children who are DHH;

• Childhood hearing loss is a relatively low incidence

technologies (e.g., digital hearing aids, cochlear implants) condition, which means that children who are DHH may

and early intervention programs, enables most children live a great distance from the specialized services they

who are DHH to achieve on par with their hearing peers need;

(Koehlinger, Owen Van Horne, & Moeller, 2013). Such • The lack of a “critical mass” of children who are DHH in

positive outcomes are most likely, however, if children are a given area, particularly rural areas, makes it difficult to

identified within the first months after birth and receive find appropriately trained early intervention providers;

appropriate medical, audiological, and educational and

services (McCann et al., 2009). • Even in densely populated areas, accessing professionals

who are knowledgeable and trained can be challenging

Although the benefits of early intervention for given the geographic dispersion of children who are

children who are DHH have been demonstrated, many of DHH, the shortage of adequately trained professionals,

these children are still not receiving appropriate services and scheduling or transportation constraints.

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129) 3

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

Because of recent improvements in information and Method

communication technology, telehealth has the potential

of addressing these challenges. Tele-intervention (TI), A randomized control trial was employed, including the

also referred to as virtual home visits (VHV), has the collection of child, family, provider, and cost data. Pretest

potential to ensure families of children with special needs data were collected prior to the six-month intervention

– including those who are DHH – receive family-centered, period, followed by post-test data collection.

routines-based early intervention services in the natural

environment. Participants

Over a decade ago, the American Speech-Language-

Hearing Association (Rosenfeld, 2002) reported that Families enrolled in the Utah Schools for the Deaf and

11% of survey respondents used telepractice to provide Blind (USDB) Parent Infant Program (PIP) were invited

services. More recently, a survey of Early Hearing to participate in this study. Thirty-five families whose

Detection and Intervention (EHDI) systems conducted primary language was English were randomly assigned

by the National Center for Hearing Assessment and to TI or traditional in-person intervention groups. Children

Management (NCHAM, 2010) found that of 48 US states in each group were matched on age, degree of hearing

and territories, 42% had telehealth or telepractice efforts loss, geographic location (i.e., rural or urban), and

under way or planned, primarily for early intervention and communication modality (American Sign Language (ASL)

communication-related therapies. To advance this effort, or Listening and Spoken Language (LSL). Of the initial

the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association 38 families, both pre-and post-test data were collected

(ASHA, 2005a; 2005b) issued the statement, “telepractice for 27 families and included in subsequent analyses. Of

is an appropriate model of service delivery for the the eight families who were randomly assigned but not

profession of speech-language pathology. Telepractice included in the data reported here, three families moved

may be used to overcome barriers of access to services out of the service area before the study was completed,

caused by distance, unavailability of specialists … and one withdrew from the study because they preferred to

impaired mobility (p. 1).” not receive TI services, and four did not have child pretest

Unfortunately, few rigorous studies of the efficacy or data. Additionally, one family included in the analysis was

cost-effectiveness of services provided through two-way randomly assigned to the TI group but refused TI services

conferencing systems have been conducted (Hjelm, 2005; after the first visit though they continued to receive in-

Mashima & Doarn, 2008; Scott et al., 2007; Wootton, person visits. Because of the “intent to treat” with TI

2001). A recent monograph provides the most current services, their data were included with the TI group in

published information about the use of TI to support the analyses. As shown in Table 1, the groups were well

early intervention to infants and toddlers who are DHH matched on these key variables.

(Blaiser, Edwards, Behl, & Muñoz, 2012; Behl, Houston, &

Stredler-Brown, 2012). Similar to previous literature on this

topic, articles in the monograph describe applications of Table 1. Family and Child Characteristics at Beginning

this technology and draw attention to the need for better of Study

evidence, with very little evidence being reported.

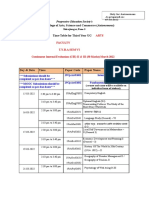

In response to the need for higher quality evidence, a Characteristic TI Group In-Person Group

study was designed to compare the costs and effects of

TI compared to traditional in-person early intervention Final Sample Size 13 14

service delivery. The study engaged providers and Average child age 18 (10-28) 19 (2-33)

families from a state-wide early intervention program for in months (range)

infants and toddlers who were DHH.

Male/Female 6/7 4/10

Additional Disabilities 2 Multiple, 1 Multiple,

1 Down syndrome 1 Down syndrome

Cochlear Implants 2 2

Communication choice: 5/8/0 5/8/1

ASL/LSL/Undecided

Nine PIP providers were involved in delivery of the early

4 International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129)

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

intervention services with each provider serving children for the LDS scales were established in previous studies,

in both groups (TI and in-person). Immediately prior to the reflecting strong inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability,

start of the study period, each provider participated in a and internal consistency (Strong, Clark, Barringer,

2-hour training covering use of equipment, preparation Walden, & Williams, 1992; Tonelson, 1980).

procedures, and typical session routines. Video examples

of TI sessions were viewed. Over the first few weeks of Caregiver and provider perceptions

the study, providers were contacted regularly to monitor

challenges with the equipment, connectivity, or other Researcher-developed self-report surveys administered

service delivery issues. No directed training pertaining to families in the TI group as well as to providers were

to the use of coaching or other best practices was used as pre- and post-test measures. Surveys included

provided beyond what the providers received within their Likert-type items as well as open-ended questions

employment setting. pertaining to perceptions about the benefits and

challenges of using TI as well as their own comfort with

Intervention the use of TI.

During the six-month period from January through Home visit quality

June 2013, families in each of the groups were scheduled

to receive PIP services in accordance with their The quality of intervention and interpersonal dynamics

Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). The mean of the intervention sessions were rated using the Home

number of prescribed monthly sessions was two visits Visit Rating Scales-Adapted & Extended (HOVRS-A+;

per month. Children in the TI group received one of these Roggman et al., 2012), which is designed to measure

visits via two-way video conferencing. A second visit excellence based on evidence-based practices for home

with the same provider was an in-person home visit as visits with families of children ages birth to 24 months.

required by state Part C policies. The scales measure four indicators of home visit quality

Families in the TI group and PIP providers were based on the home visitor’s responsiveness to family,

provided with laptops preprogrammed with Voice over relationship with family, facilitation of the parent-child

Internet Protocol (VoIP) software with additional software interaction, and non-intrusiveness and collaboration.

and procedures to ensure compliance with the Health Three additional scales provide indicators of home

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). visitor effectiveness during the home visit: parent-child

Connectivity speeds for families and providers were interaction, parent engagement, and child engagement.

assessed prior to intervention. Five of the families and one Strong internal consistency is reported (Vogel et al., 2011).

provider in the study had no Internet access or insufficient Video recordings of four families in the TI group and four

bandwidth, and a variety of methods were used to ensure families in the comparison group with matched providers

adequate connectivity. Midway through the study, all were independently coded by one of the authors of the

families who had insufficient bandwidth were upgraded HOVRS-A+.

to a minimum of 1.5 Mbps, with the costs covered by the

researchers. Costs

The costs of providing services (TI and in-person) were

Instrumentation measured using a researcher-developed cost form that

included service delivery time; travel time and expenses;

A variety of measures were used to assess the and equipment and Internet service costs. Additional

children’s developmental outcomes, user perceptions, technology costs and technical support time were also

quality of the intervention, and costs. included. Providers completed cost forms every other

week during four months of the study.

Child outcomes

The amount of progress made by each child in receptive

and expressive language was measured using the SKI-

HI Language Development Scale (LDS; Hope Publishing,

2004). This criterion-referenced scale is developmentally

ordered and contains a list of communication and

language skills in varying intervals for different ages.

Each age interval is represented by enough observable

receptive and expressive language skills to obtain a good

profile of a child’s language ability. Reliability and validity

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129) 5

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

Results Caregiver and provider perceptions

The following results are based on pre-post measures After about three months, caregivers in the TI group

following a six-month intervention period. rated their satisfaction a 6.9 on a 10-point scale with 10

being highly satisfied. An additional self-report survey

Child outcomes was administered to providers at postest. Post-test

data revealed that, compared to the onset of the study,

As shown in Figure 1, mean scores in receptive and caregivers felt that TI services were helpful in reducing the

expressive language skills for children in the TI group number of visits missed due to illness or bad weather and

were higher than children in the comparison group did not interfere with their relationships and interactions

when covaried on pretest scores and chronological age. with providers. The most significant benefit reported

Differences in favor of the TI group were statistically by families was that TI facilitated family engagement

significant for expressive language (p =.03, standardized during sessions and put the family “in the driver’s seat.”

mean difference effect size, or SMDES = .40), but not for The biggest challenge and most frustrating aspect was

receptive language (p = .22, SMDES = .23). Effect sizes connectivity. Caregivers reported that they learned how

in favor of the TI group for both expressive and receptive to help their child more through TI than in traditional

language differences are noteworthy. in-person visits, and that they were more involved in the

TI sessions. In addition to difficulties with technology,

caregivers reported challenges with keeping their child

engaged and feeling that the visit was less personal than

the in-person visit.

A post-test self-report survey was administered to

providers to obtain their perspectives on the strengths

and challenges of TI. Post-test data revealed that,

compared to the onset of the study, providers used video

conferencing technology more in their personal life, felt

more comfortable with coaching, and shifted the focus of

interactions in sessions from parent-visitor interactions

to parent-child interactions. Providers continued to have

reservations about personal contact with families in a

TI model and providing therapy that supported natural

environments. Based on qualitative responses, providers

appreciated the benefits of reduced travel time in serving

families who live far away as well as avoiding exposure to

an ill family member.

Home visit quality

Recordings of sessions independently scored by an

Figure 1. Pre- and post-test differences in LDS scores for

In-person and TI groups. author of the HOVRS-A+ indicated that average ratings

favor the TI group. Group means, standardized mean

difference effect sizes (SMDES), and the results of

statistical tests of differences between groups are shown

in Table 2. All differences favor the TI group except child

engagement, though differences in child engagement are

quite small as shown in Figure 2. Additionally, the group

difference for Parent Engagement during Home Visit was

statistically significant (p < .05), indicating that parents

in the TI group were more engaged during the TI session

than parents in the comparison group during the home

visit.

6 International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129)

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

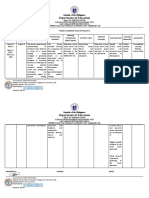

Table 2. Statistics Showing HOVRS Differences between TI for the two groups (20 and 17 minutes for the in-

and Comparison Groups person group, and 19 and 22 minutes for the TI group,

respectively). Consequently,

the cost of salaries and wages

HOVRS Scale Mean: Mean: Standard SMDES p-value for providers to prepare,

TI Comparison Error

deliver, and document services

Home Visitor Responsiveness 4.177 4.073 0.459 0.2 0.645 was assumed to be the same

to Family (HVRESP) for children in both groups.

For each child in the

Home Visitor Relationship 5.485 4.765 0.438 1.6 0.509 in-person group, providers

with Family (HVFamRel)

drove an average of 22 miles

Home Visitor Facilitation 4.966 4.034 0.446 2.1 0.332 in each direction, requiring an

of Parent–Child Interaction extra 60 minutes of their time

(HVFacPCint) (valued at $55 per hour for

salary and benefits) and a cost

Home Visitor 4.058 3.192 0.656 1.3 0.654

Non-Intrusiveness & of $22 for driving expenses

Collaboration (HVCollab) (valued at $0.50 per mile).

Thus, each home visit cost an

Parent–Child Interaction 5.875 4.875 0.382 2.6 0.160 additional $77 in provider time

during Home Visit (PCInteract) and expenses as compared

Parent Engagement during 5.599 4.401 0.200 6.0 0.017 to a TI visit. Additional costs

Home Visit (PEngage) for children in the TI group

included enhanced Internet

Child Engagement during 5.186 5.314 0.493 -0.3 0.174 service and software licensing

Home Visit (CEngage) fees ($60/month) for the

provider, and for each family

a computer, microphone,

camera and monitor (one time cost of $1,000), enhanced

Internet service and software costs ($60 per month per

family), and their share of the technology specialist who

was responsible for system set up, training parents and

providers in using the equipment, and ongoing support

($50 per month per family).

Using these figures, the estimated cost of providing

services for a two-year period to 15 families (assumed

to be the average “caseload” for a single provider) is

shown in Figure 3. As seen in this figure, if every child

received an average of only one visit per month, in-person

services are less expensive than TI services. However, if

more frequent services were provided, TI services have a

growing financial advantage. If 3-4 visits were provided to

each child each month (similar to what is reported in an

ongoing study being conducted by the National Institutes

of Health (Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss, 2013),

the cost savings for providing services to 15 families using

TI instead of in-person services would be $56,280 to

$86,970 over a 24 month period. Such cost savings, taken

Figure 2. HOVRS differences between TI and comparison together with the evidence that children in the TI group

groups. (as described herein) make as good or better progress

in receptive and expressive language, suggests that TI

should be seriously considered as a way of delivering

Costs services to all 0-3 year old children who are DHH.

The amount of time providing services to children was

similar for both groups (59 minutes for in-person and

51 minutes for TI). Time spent preparing for visits and

documentation/record keeping was almost identical

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129) 7

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

Both provider and caregiver perceptions of

TI improved dramatically when connectivity

issues were solved. Programs interested in

implementing TI services need to consider and

account for cost and time related to making

sure that providers and families have sufficient

bandwidth. One of the most salient results of

this study was the value of setting the goal

of 1.5 Mbps upload and download speeds

to ensure adequate communication quality.

Figure 3. Cost savings for TI when compared to In-person This means that families living in remote areas

home visit. without access to sufficient bandwidth are still likely to

face challenges in accessing important services.

The cost analysis provided evidence that, given an

average of three to four intervention sessions per month,

Discussion the cost savings from TI over time could be substantial.

Given the financial challenges faced by many early

This randomized controlled study contributes to our intervention programs as the demand for their services

current knowledge about the costs and effects of TI when grow, the results of this study suggest that TI is a viable

compared to in-person home visits. Though the sample method to ensure the needed intensity of services can be

sizes in this study were relatively small and the duration of provided.

the study was short, the resulting evidence indicates that There are other potential benefits of TI that were not

children of families who receive TI services (as described targeted for measurement, yet are worth noting. For

herein) make more developmental progress in language example, one family preparing for a cochlear implant

skills than children receiving services through in-person surgery was able to receive additional consultation via

early intervention home visits. Both families and providers TI from an audiologist about device choice and have

indicated that a benefit of TI was the convenience of not this consultation held at a time when the father could be

leaving home or office to travel across town in traffic or present. This would probably not have been possible if

bad weather, and when children or other family members the audiologist would have been required to make an in-

were sick. person visit. Such anecdotes reflecting interdisciplinary

This study’s use of a comprehensive measure of the teaming point to another important outcome to be

quality of intervention is also a significant contribution to measured in future studies.

the investigation of TI. Best practices in early intervention This study has limitations that must be considered in

encourage providers to facilitate and “coach” families the interpretation of the results. First, although the sample

in interactions with their children. As shown above, size was larger than most other TI studies with children

TI resulted in increased parent-child engagement, as who are DHH reported in the literature, studies with even

opposed to child-provider interactions.These results larger samples are needed. Second, the short duration

could be due to the nature of the delivery system itself of the intervention period and the limited intensity of

whereby the providers interact more with caregivers than service delivery may have reduced the documentation

children during TI-based early intervention sessions. As a of potential outcomes, particularly given the initial

result, TI providers facilitate parent-child interactions and connectivity challenges faced by some of the TI families.

ultimately improve the caregiver’s ability to nurture their Additional research using standardized measures of child

child’s development, through the use of TI. Though the development versus criterion-referenced tools also would

sample included in this analysis was small, it accounted strengthen the evidence base. Finally, there are additional

for provider differences by including families in each factors to be investigated in regard to the role of TI. For

group for each provider. However, further research with example, the degree of training and skill set required for

a larger sample size is needed to replicate these results. optimal TI implementation is an area of further study.

Additionally, monitoring changes in the quality of home In conclusion, this study demonstrated that TI has the

visits over time would be a valuable contribution. potential to ensure that all families who have children who

Provider and caregiver perceptions varied greatly are DHH, regardless of their geographic location, have

in terms of support for TI. Two families withdrew from access to high quality, specialized early intervention. TI

the study, preferring not to use the TI service delivery not only increases a family’s access to providers, but, due

model. The reasons given suggest that the families felt to the nature of the TI interactions, also has the potential

that the additional effort associated with learning a new to be more successful in supporting the use of “coaching”

technology was not desirable or feasible for them at families in their natural environments. This message

the time. Technology challenges faced by many of the is important to share with payors of early intervention

partcipants during the first few months of the study also services, who may be skeptical of TI (Cason, Behl, &

influenced provider and caregiver satisfaction with TI.

8 International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129)

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

Ringwalt, 2012). It is likely the reality of limited budgetary References

resources to meet the growing demand of services will

lead to the acceptance of TI. It behooves TI supporters to 1. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

be prepared with evidence to support this direction. (2005a). Audiologists providing clinical services via

telepractice. [Position statement].

2. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

(2005b). Speech-language pathologists providing clinical

services via telepractice. [Position statement].

3. Behl, D., Houston, K. T., & Stredler-Brown, A. (2012). The

value of a learning community to support telepractice for

infants and toddlers with hearing loss. Volta Review, 112,

313-296.

4. Blaiser, K., Edwards, M., Behl, D., & Muñoz, K. (2012).

Tele-intervention services at Sound Beginnings at Utah

State University. Volta Review, 112, 365-372.

5. Cason, J., Behl, D., & Ringwalt, S. (2012). Overview

of states’ use of telehealth for the delivery of early

intervention (IDEA Part C) services. International Journal

of Telerehabilitation, 4, 39-46. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2012.6105

6. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013).

Summary of national CDC 2011 EHDI data. Retrieved

from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-

data2011.html

7. Hjelm, N. M. (2005). Benefits and drawbacks of

telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 11,

60-70.

8. Hope Publishers. (2004). Language Development Scale.

Retrieved from http://www.hopepubl.com

9. Koehlinger, K., Owen Van Horne, A. J., & Moeller, M. P.

(2013). Grammatical outcomes of 3 & 6 year old children

with mild to severe hearing loss. Journal of Speech-

Language-Hearing Research. Manuscript in preparation.

10. Mashima, M. & Doarn, C. (2008). Overview of telehealth

activities in speech-language pathology. Telemedicine

and e-Health, 14, 1101-1117.

11. McCann, D.C., Worsfold, S., Law, C.M., Mullee, M.,

Petou, S., Stevenson, J.,… Kennedy, C.R. (2009).

Reading and communication skills after universal

newborn screening for permanent childhood hearing

impairment. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94, 293-

297.

12. National Center for Hearing Assessment and

Management. (2010). NCHAM 2010 Telehealth Survey.

Retrieved from http://www.infanthearing.org/telehealth/

docs/Telehealth%20Survey%20Summary.pdf

13. Outcomes of children with hearing loss: A study of

children ages birth to six. 2013. Funded by the National

Institute of Deafness and Other Communicative

Disorders grant # DC009560. Retrieved from http://www.

uiowa. edu/~ochl.

14. Roggman, L.A., Cook, G.A., Innocenti, M.S., Jump

Norman, V.K., Christiansen, K., Boyce, L. K., …

Hallgren, K. (2012). Home Visit Rating Scales—Adapted

and Extended (HOVRS-A+). Baltimore, MD: Brooks

Publishing.

15. Rosenfeld, M. (2002, October). Report on the ASHA

speech-language pathology health care survey.

Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing

Association.

16. Scott, R.E., McCarthy, F.G., Jennett, P.A., Perverseff,

T., Lorenzetti, D., Saeed, A., … Yeo, M. (2007).

Telehealth outcomes: A synthesis of the literature and

recommendations for outcome indicators. Journal of

Telemedicine and Telecare, 13(Suppl)2, 1-38.

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129) 9

International Journal of Telerehabilitation • telerehab.pitt.edu

17. Strong, C. J., Clark, T. C., Barringer, D. G., Walden,

B. E., & Williams, S. A. (1992). SKI-HI home-based

programming for children with hearing impairments:

Demographics, child identification, and program

effectiveness, 1979-1991. A three-year study conducted

at the SKI-HI Institute. Logan, UT: SKI-HI Institute, Utah

State University.

18. Tonelson, S. W. (1980). A validation study of the SKI-HI

language development scale (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

(AAT 8102583)

19. Toward Equality. (1988). A report to the Congress

of the United States: Toward equality- Commission

on Education of the Deaf. Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

20. Vogel, C.A., Boller, K., Xue, Y., Blair, R., Aikens, N.,

Burwick, A., … Stein, J.. (2011). Learning as we go:

A first snapshot of Early Head Start programs, staff,

families, and children. Report No. 2011-7. Washington,

DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation,

Administration for Children and Families, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services.

21. White, K. R., (2007). Early intervention for children with

permanent hearing loss: Finishing the EHDI revolution.

The Volta Review, 106, 237-258.

22. White K. R., Forsman, I., Eichwald, J., & Muñoz, K.

(2010). The evolution of early hearing detection and

intervention programs in the United States. Seminars in

Perinatology, 34, 170-179.

23. Wootton, R. (2001). Recent advances: Telemedicine.

British Medical Journal, 323, 557-560.

10 International Journal of Telerehabilitation • Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall 2013 • (10.5195/ijt.2013.6129)

You might also like

- Overcoming Barriers To Using Telehealth For Standardized Language AssessmentsDocument11 pagesOvercoming Barriers To Using Telehealth For Standardized Language Assessments賴奕全No ratings yet

- 2017 Wales THE EFFICACY OF TELEHEALTH DELIVERED SPEECHDocument16 pages2017 Wales THE EFFICACY OF TELEHEALTH DELIVERED SPEECHpaulinaovNo ratings yet

- Clinician Perspectives On Telehealth Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument16 pagesClinician Perspectives On Telehealth Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder During The COVID-19 PandemicrenatoNo ratings yet

- Aud 0000000000000212Document10 pagesAud 0000000000000212axel pqNo ratings yet

- Kegunaan Bahan BangunanDocument11 pagesKegunaan Bahan BangunanyofitaNo ratings yet

- Treating Rural Pediatric Obesity Through Telemedicine: Baseline Data From A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesTreating Rural Pediatric Obesity Through Telemedicine: Baseline Data From A Randomized Controlled Trialapi-546998503No ratings yet

- Hodge 2018Document7 pagesHodge 2018Ines Arias PazNo ratings yet

- 1-22 Cole, Pickard Et Al., 2019 TelehealthDocument8 pages1-22 Cole, Pickard Et Al., 2019 Telehealthamericangurl1284681No ratings yet

- Early Intervention Guidelines for Deaf ChildrenDocument42 pagesEarly Intervention Guidelines for Deaf ChildrenNadzira KarimaNo ratings yet

- EhswallDocument15 pagesEhswallapi-533702960No ratings yet

- Assessment of Hearing Loss in ChildrenDocument25 pagesAssessment of Hearing Loss in ChildrenCristóbal Murillo MuñozNo ratings yet

- Part C EligibilityDocument6 pagesPart C Eligibilityapi-260192872No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0738399121001701 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0738399121001701 MainYaumil FauziahNo ratings yet

- Early Intervention in Children 0 6 Years With A R 2014 Hong Kong Journal oDocument9 pagesEarly Intervention in Children 0 6 Years With A R 2014 Hong Kong Journal oCostiNo ratings yet

- Alighieri 2020Document10 pagesAlighieri 2020Natalia AlberoNo ratings yet

- Inclusion of Toddlers - AutismDocument18 pagesInclusion of Toddlers - AutismVarvara MarkoulakiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric TeleNP Feasibility and RecommendationsDocument11 pagesPediatric TeleNP Feasibility and RecommendationsInes Arias PazNo ratings yet

- Báo 3Document9 pagesBáo 3Thanh Nhàn Nguyễn ThịNo ratings yet

- Early Hearing Detection and InterventionDocument10 pagesEarly Hearing Detection and InterventionNina KondićNo ratings yet

- J Jfludis 2021 105843Document21 pagesJ Jfludis 2021 105843ANDREA MIRANDA MEZA GARNICANo ratings yet

- Health Care Changes For Children With Special Health CareDocument8 pagesHealth Care Changes For Children With Special Health CareexaNo ratings yet

- Capstone HuacasiDocument40 pagesCapstone Huacasiapi-397532577No ratings yet

- Comparing hearing screening outcomes using smartphone audiometry by specialist and non-specialist healthcare workersDocument10 pagesComparing hearing screening outcomes using smartphone audiometry by specialist and non-specialist healthcare workersNadia DhyaNo ratings yet

- Csa ExaminationDocument21 pagesCsa ExaminationCorina IoanaNo ratings yet

- Home-Based Early Intervention With Families of Children With Disabilities: Who Is Doing What?Document25 pagesHome-Based Early Intervention With Families of Children With Disabilities: Who Is Doing What?eebook123456No ratings yet

- Efficacy of A Reading and Language Intervention For Children With Down Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesEfficacy of A Reading and Language Intervention For Children With Down Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled TrialRubashni SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Sarah Dababnah, Susan L. Parish, Lauren Turner Brown, Stephen R. HooperDocument7 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Sarah Dababnah, Susan L. Parish, Lauren Turner Brown, Stephen R. HooperDanya KatsNo ratings yet

- Pathways To Services For Children With Cerebral Palsy in Selangor and The Federal Territory, Kuala LumpurDocument4 pagesPathways To Services For Children With Cerebral Palsy in Selangor and The Federal Territory, Kuala LumpurAznaeym AbdLatifNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Co-Occurring Disabilities in Young Children Who AreDocument24 pagesAssessment of Co-Occurring Disabilities in Young Children Who AreMariana BucurNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossDocument6 pagesKnowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossMaria P12No ratings yet

- Cochlear ImplantsDocument53 pagesCochlear ImplantsSovitJungBaralNo ratings yet

- 2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Document17 pages2019 - JSLHR S 18 0301Andreia TavaresNo ratings yet

- Practice: Social Work in ActionDocument17 pagesPractice: Social Work in ActionUSFMFPNo ratings yet

- Telepsychiatry: Effective, Evidence-Based, and at A Tipping Point in Health Care Delivery?Document34 pagesTelepsychiatry: Effective, Evidence-Based, and at A Tipping Point in Health Care Delivery?Riza Agung NugrahaNo ratings yet

- AAPD Teledentistry 2021Document2 pagesAAPD Teledentistry 2021Francisca Abarca CifuentesNo ratings yet

- A North Dakota Prevalence Study of Nonverbal School-Age ChildrenDocument13 pagesA North Dakota Prevalence Study of Nonverbal School-Age ChildrenJaavyeraa' BelenNo ratings yet

- Nur 330 - Health Promotion ProjectDocument12 pagesNur 330 - Health Promotion Projectapi-375928224No ratings yet

- Ford 2003Document9 pagesFord 2003Arif Erdem KöroğluNo ratings yet

- 2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inDocument17 pages2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inLucia CavasNo ratings yet

- Beliefs of Filipino Caregivers On Occupational Therapy Through TelehealthDocument4 pagesBeliefs of Filipino Caregivers On Occupational Therapy Through TelehealthBETINA NICOLE SYNo ratings yet

- Guidelines AconselhamentoDocument28 pagesGuidelines Aconselhamentoraquelgsilva17No ratings yet

- Part C Early Intervention Enrollment Patterns in Low Birth Weight InfantsDocument7 pagesPart C Early Intervention Enrollment Patterns in Low Birth Weight InfantsFarin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Interact Integrate ImpactDocument11 pagesInteract Integrate ImpactSanziana SavaNo ratings yet

- Economics of Education Review 72 (2019) 30-43Document14 pagesEconomics of Education Review 72 (2019) 30-43iraastutikNo ratings yet

- Training Adults and Children with ASD to be Compliant with Dental AssessmentsDocument10 pagesTraining Adults and Children with ASD to be Compliant with Dental AssessmentsSpecial CareNo ratings yet

- The Bucharest Early Intervention Project - Adolescent Mental Health and Adaptation Following Early DeprivationDocument8 pagesThe Bucharest Early Intervention Project - Adolescent Mental Health and Adaptation Following Early DeprivationMerly JHNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Knowledge - Parents Experience of The NeuropsychiatricDocument11 pagesNegotiating Knowledge - Parents Experience of The NeuropsychiatricKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- It Felt Like There Was Always Someone There For Us Supporting ChildrenDocument10 pagesIt Felt Like There Was Always Someone There For Us Supporting ChildrenHuế Nguyễn PhươngNo ratings yet

- Child Development - 2011 - Lowell - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Child FIRST A Comprehensive Home‐Based InterventionDocument16 pagesChild Development - 2011 - Lowell - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Child FIRST A Comprehensive Home‐Based InterventionCláudia Isabel SilvaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0190740915000870 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0190740915000870 Main PDFYusranNo ratings yet

- Caso Programa TeacchDocument12 pagesCaso Programa TeacchsaraNo ratings yet

- Early Intervention Guidelines for Children with Hearing LossDocument2 pagesEarly Intervention Guidelines for Children with Hearing LossAbuzar AliNo ratings yet

- Early InterventionDocument13 pagesEarly Interventionapi-290229666No ratings yet

- OSF FinalDocument38 pagesOSF Finalinas zahraNo ratings yet

- Telehealth As A Model For Providing Behaviour AnalDocument36 pagesTelehealth As A Model For Providing Behaviour AnalNabilah AuliaNo ratings yet

- Diaryquestionnairetv 2Document17 pagesDiaryquestionnairetv 2GeorgetownELPNo ratings yet

- LR EffectivenessDocument24 pagesLR Effectivenessapi-349022556No ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Effective Strategies For Reducing Screen Time Among Young ChildrenDocument17 pagesSystematic Review of Effective Strategies For Reducing Screen Time Among Young ChildrenAdrienn MatheNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersFrom EverandClinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersNo ratings yet

- Supporting Families Experiencing Homelessness: Current Practices and Future DirectionsFrom EverandSupporting Families Experiencing Homelessness: Current Practices and Future DirectionsNo ratings yet

- Baby Mouse PatternDocument27 pagesBaby Mouse Patternlamarinescu100% (1)

- Marriage and Family Therapists Working With Couples Who Have Children With AutismDocument12 pagesMarriage and Family Therapists Working With Couples Who Have Children With AutismanaNo ratings yet

- TI Participation Consent FormDocument2 pagesTI Participation Consent FormanaNo ratings yet

- Implementing and Preparing For Home VisitsDocument10 pagesImplementing and Preparing For Home VisitsanaNo ratings yet

- Telepractice Self Eval Form PDFDocument1 pageTelepractice Self Eval Form PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Telepractice Self Eval Form PDFDocument1 pageTelepractice Self Eval Form PDFanaNo ratings yet

- DEC - RPs - 5-1-14 PDFDocument14 pagesDEC - RPs - 5-1-14 PDFanaNo ratings yet

- DEC - RPs - 5-1-14 PDFDocument14 pagesDEC - RPs - 5-1-14 PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Checklist For Determining Home Capacity For Tele PDFDocument1 pageChecklist For Determining Home Capacity For Tele PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Family Routines Inventory PDFDocument2 pagesFamily Routines Inventory PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Modern College Arts Time Table TYBA Sem VI March 2022Document2 pagesModern College Arts Time Table TYBA Sem VI March 2022Aniket SalveNo ratings yet

- PC 314 REVIEWER QUIZ 1 AND 2Document10 pagesPC 314 REVIEWER QUIZ 1 AND 2Victor S. Suratos Jr.No ratings yet

- Luo - Plo4 - Edte608 Final Assessment ProjectDocument7 pagesLuo - Plo4 - Edte608 Final Assessment Projectapi-549590947No ratings yet

- Results-Based Performance Management System (RPMS) : PortfolioDocument82 pagesResults-Based Performance Management System (RPMS) : PortfolioLilibeth Allosada LapathaNo ratings yet

- Pangasinan State UniversityDocument6 pagesPangasinan State UniversityGretz DoriaNo ratings yet

- Summury of A Research in DEDocument2 pagesSummury of A Research in DEu061542No ratings yet

- Welcome Madison 2013 2014Document97 pagesWelcome Madison 2013 2014Alexander León PuelloNo ratings yet

- Farwell SpeechDocument1 pageFarwell SpeechSaurabh ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- LAS 432 Technology, Society, and CultureDocument5 pagesLAS 432 Technology, Society, and CultureAlan MarkNo ratings yet

- Eng8 WLP Q3 Week3Document3 pagesEng8 WLP Q3 Week3ANNABEL PALMARINNo ratings yet

- Devachan or HeavenworldDocument14 pagesDevachan or HeavenworldOldan AguilarNo ratings yet

- Mukhyamantri Yuva Scholarship DetailsDocument1 pageMukhyamantri Yuva Scholarship DetailsUtsavNo ratings yet

- Study and Reference Guide-Instructor RatingDocument7 pagesStudy and Reference Guide-Instructor RatingJeff LightheartNo ratings yet

- Good Math Lesson PlansDocument36 pagesGood Math Lesson PlansZulsubhaDaniSiti100% (1)

- Architectural School Design Study CasesDocument117 pagesArchitectural School Design Study CasesRazan KhrisatNo ratings yet

- Task Sheet 1.1-5 RevisedDocument3 pagesTask Sheet 1.1-5 RevisedEL FuentesNo ratings yet

- WEB-Robot Awakening Kinder 2 (English)Document131 pagesWEB-Robot Awakening Kinder 2 (English)Administracion TuproyectoNo ratings yet

- Night Figurative LanguageDocument2 pagesNight Figurative Languageapi-542555028No ratings yet

- Fixed Mindset Vs Growth MindsetDocument16 pagesFixed Mindset Vs Growth MindsetTop Gear AutosNo ratings yet

- Date Sheet Term II Assessment II 2022-23Document2 pagesDate Sheet Term II Assessment II 2022-23nameNo ratings yet

- Ingles 1 Modelo de ExamenDocument5 pagesIngles 1 Modelo de ExamenNiki LMNo ratings yet

- Classroom Structure ChecklistDocument1 pageClassroom Structure ChecklistBella Bella100% (1)

- Accreditation Standard For Quality School Governance - Application - 1Document10 pagesAccreditation Standard For Quality School Governance - Application - 1Ankur DhirNo ratings yet

- Par Statements - Updated 2016Document2 pagesPar Statements - Updated 2016K DNo ratings yet

- B.ed SyllabusDocument123 pagesB.ed SyllabusextraworkxNo ratings yet

- NetApp Partner LevelsDocument1 pageNetApp Partner LevelsPanzo Vézua GarciaNo ratings yet

- Contoh Soalan Public PerceptionDocument27 pagesContoh Soalan Public Perception12035safyaabdulmalikNo ratings yet

- Karina Castillo: I Am A 30 Year Old Woman Looking To Further Expand My Career As A Session Singer in The Music IndustryDocument7 pagesKarina Castillo: I Am A 30 Year Old Woman Looking To Further Expand My Career As A Session Singer in The Music IndustryKarina PorterNo ratings yet

- Allison ResumeDocument2 pagesAllison Resumeapi-351570174No ratings yet

- Bridge Technical Expert to Modernize Nepal's Bridge TechnologiesDocument6 pagesBridge Technical Expert to Modernize Nepal's Bridge TechnologiesRam NepaliNo ratings yet