Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Probiotics: Clinical Review

Uploaded by

IrhamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Probiotics: Clinical Review

Uploaded by

IrhamCopyright:

Available Formats

clinical review Probiotics

clinical review

Probiotics

Nancy Toedter Williams

I

n recent years, both research and

consumer interest in probiotics Purpose. The pharmacology, uses, dosag- didiasis. There is no consensus about the

have grown. Increasing clini- es, safety, drug interactions, and contrain- minimum number of microorganisms that

dications of probiotics are reviewed. must be ingested to obtain a beneficial ef-

cal evidence supports some of the

Summary. Probiotics are live nonpatho- fect; however, a probiotic should typically

proposed health benefits related to genic microorganisms administered to contain several billion microorganisms to

the use of probiotics, particularly in improve microbial balance, particularly increase the chance that adequate gut

managing certain diarrheal diseases. in the gastrointestinal tract. They consist colonization will occur. Probiotics are gen-

Probiotics are defined as “live micro- of Saccharomyces boulardii yeast or lactic erally considered safe and well tolerated,

organisms which when administered acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and with bloating and flatulence occurring

in adequate amounts confer a health Bifidobacterium species, and are regulated most frequently. They should be used cau-

as dietary supplements and foods. Probi- tiously in patients who are critically ill or

benefit on the host.”1 The term pro-

otics exert their beneficial effects through severely immunocompromised or those

biotic was initially used in the 1960s various mechanisms, including lowering with central venous catheters since sys-

and comes from a Greek word mean- intestinal pH, decreasing colonization and temic infections may rarely occur. Bacteria-

ing “for life.” Although a relatively invasion by pathogenic organisms, and derived probiotics should be separated

new word, the beneficial effects of modifying the host immune response. from antibiotics by at least two hours.

certain foods containing live bacteria Probiotic benefits associated with one Conclusion. Probiotics have demonstrated

have been recognized for centuries. species or strain do not necessarily hold efficacy in preventing and treating vari-

true for others. The strongest evidence ous medical conditions, particularly those

However, it was not until the early

for the clinical effectiveness of probiotics involving the gastrointestinal tract. Data

20th century that investigators sug- has been in the treatment of acute diar- supporting their role in other conditions

gested gut flora could be altered with rhea, most commonly due to rotavirus, are often conflicting.

beneficial bacteria replacing harmful and pouchitis. More research is needed to

microbes, leading to the concept of clarify the role of probiotics for preventing Index terms: Antiinfective agents; Contrain-

probiotics.2-4 antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Clostridium dications; Diarrhea; Dietary supplements;

Probiotics, which are regulated difficile infection, travelers’ diarrhea, ir- Dosage; Drug interactions; Mechanism of

ritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, action; Probiotics; Regulations; Toxicity

as dietary supplements and foods,

Crohn’s disease, and vulvovaginal can- Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2010; 67:449-58

consist of yeast or bacteria. They are

available as capsules, tablets, packets,

or powders and are contained in vari-

ous fermented foods, most common-

ly yogurt or dairy drinks. Probiotic bacillus and Bifidobacterium species. cable to another strain, even within

products may contain a single mi- The yeast Saccharomyces boulardii one species. Therefore, generaliza-

croorganism or a mixture of several also appears to have health benefits. tions about potential health benefits

species. Table 1 lists common micro- It is noteworthy that probiotic effects should not be made.2,5,6,8,9

organisms used as probiotics. The tend to be specific to a particular The rationale for using probiotics

most widely used probiotics include strain, so a health benefit attributed involves restoring microbial balance.

lactic acid bacteria, specifically Lacto- to one strain is not necessarily appli- More than 500 different bacterial

Nancy Toedter Williams, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCNSP, is Associate The author has declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Professor of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, Southwestern

Oklahoma State University, c/o Norman Regional Health System, Copyright © 2010, American Society of Health-System Pharma-

Pharmacy Services, 901 North Porter, Box 1308, Norman, OK 73070- cists, Inc. All rights reserved. 1079-2082/10/0302-0449$06.00.

1308 (nancy.williams@swosu.edu). DOI 10.2146/ajhp090168

The early guidance of Joseph Pepping, Pharm.D., is acknowledged.

Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010 449

clinical review Probiotics

Table 1.

tion), colonize and reproduce in the decrease the symptoms of lactose

Microorganisms Used as gut, attach and adhere to the intesti- intolerance.11,15-17

Probiotics2,5-7 nal epithelium, and stabilize the bal- Other illnesses not associated

ance of the gut flora. Furthermore, with the gastrointestinal tract or

Bacteria probiotic strains must be safe and gut microbiota, including various

Lactobacillus species effective in humans, remain viable urogenital problems (e.g., bacterial

L. acidophilus for the shelf life of the product, and vaginosis, candidal vaginitis, urinary

L. bulgaricus not have pathogenic properties.2,9-11 tract infections), may also respond

L. casei

Products containing more than one to probiotics.2,6,8,15 Probiotics have

L. crispatus

L. fermentum

organism are particularly appeal- also been studied for their role in

L. gasseri ing for two reasons: colonization in treating upper respiratory infections

L. johnsonii some patients may occur with one (e.g., acute otitis media); reducing

L. lactis strain and not another, and probiotic the risk of colon and bladder cancer,

L. plantarum mixtures may be synergistic in sup- allergic diseases, and atopy; boosting

L. reuteri pressing pathogens. immune response; and preventing

L. rhamnosus GG dental caries.2,14,15,17,18

Bifidobacterium species Uses

B. adolescentis Probiotics have been used for the Pharmacology

B. animalis

prevention and treatment of various Although the exact mechanisms of

B. bifidum

medical conditions and to support action of probiotics are not known,

B. breve

B. infantis

general wellness. Some of their bene- several have been proposed. As

B. lactis ficial health effects have been validat- mentioned previously, the most fre-

B. longum ed, while other uses are supported by quently used probiotics include lactic

Bacillus cereus limited evidence. Not only are probi- acid bacteria, particularly Lactoba-

Enterococcus faecalisa otic effects strain specific, probiotic cillus and Bifidobacterium species.

Enterococcus faeciuma products may vary from each other, These bacteria produce lactic acid,

Escherichia coli Nissle and greater benefits may be seen with acetic acid, and propionic acid, which

Streptococcus thermophilus one lot of probiotics versus another lower the intestinal pH and suppress

Yeast due to the complexity of quality the growth of various pathogenic

Saccharomyces boulardii

control with live microorganisms. bacteria, thereby reestablishing the

a

Concerns exist about using enterococci as pro- balance of the gut flora.6,7

Furthermore, combination agents

iotics because of possible pathogenicity and van-

b

comycin resistance. can make it challenging to quantify Another mechanism of bacterial

particular clinical benefits.2,12,13 interference involves the production

Illnesses associated with the gas- of various substances, such as hydro-

species reside in the adult gastroin- trointestinal tract have been a com- gen peroxide, organic acids, bacterio-

testinal tract.6,8 Some microbes are mon target of probiotics, mainly due cins, and biosurfactants, that are toxic

considered beneficial to the human to their ability to restore gut flora. to pathogenic microorganisms.7,10,14

host, while others are pathogenic. The strongest evidence for the use of One probiotic with this abil-

An appropriate balance of gut flora probiotics lies in the treatment of cer- ity is Lactobacillus species strain GG,

is generally maintained; however, tain diarrheal diseases, especially ro- which has been shown to secrete a

antibiotics, immunosuppressive taviral diarrhea in children. Clinical low-molecular-weight compound

medications, surgery, and irradiation studies have also supported the role that inhibits a broad spectrum of

can cause an increase in the patho- of probiotics in treating pouchitis.2,8,9 gram-positive, gram-negative, and

genic bacteria and disrupt this ho- Data are inconsistent regarding the anaerobic bacteria. 19 In addition,

meostasis. Probiotics, which contain efficacy of probiotics for antibiotic- S. boulardii, a nonpathogenic yeast,

beneficial bacteria and yeast, may associated diarrhea (AAD) and may have a role in Clostridium dif-

restore the microbial balance in the travelers’ diarrhea. 2 ,8 A lthough ficile infection by producing a pro-

gastrointestinal tract.5-7 clinical trial results are conflicting, tease that decreases the toxicity of

In order for probiotics to be suc- probiotic therapy may also be ben- C. difficile toxins A and B.20

cessful, they must possess certain eficial in the treatment of Crohn’s Probiotics also decrease coloniza-

characteristics. Probiotic organisms disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), ir- tion of pathogenic organisms in the

must be able to withstand passage ritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and urinary and intestinal tracts by com-

through the gastrointestinal tract Helicobacter pylori infections.5,8,14,15 petitively blocking their adhesion to

(i.e., survive acid and bile degrada- Probiotics have also been shown to the epithelium.14 Lactobacilli have

450 Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010

clinical review Probiotics

been shown to inhibit the attachment Nutrition conducted a double-blind, which were prescribed for five days.

of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumo- placebo-controlled, multicenter Only two preparations—LGG and a

niae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa to study involving 287 children age mixture of four bacterial strains (Lac-

uroepithelial cells and intestinal epi- 1–36 months from 10 countries who tobacillus delbrueckii var bulgaricus,

thelial cells.21,22 This inhibition may were admitted to the hospital with Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactoba-

occur because lactobacilli cause steric moderate-to-severe diarrhea, most cillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacte-

hindrance and upregulate intestinal commonly due to rotavirus or an rium bifidum)—were associated with

mucins, which are high-molecular- unknown pathogen.25 The patients a significantly shorter median dura-

weight glycoproteins produced by were randomized to receive oral re- tion of diarrhea (78.5 and 70 hours,

epithelial cells; the result is the for- hydration solution plus placebo or respectively; p < 0.001) compared

mation of a protective barrier. In ad- oral rehydration solution plus a live with children who received oral rehy-

dition, lactobacilli strengthen the gut preparation of LGG. Patients who dration solution alone (115.5 hours).

mucosal barrier by stabilizing tight were given LGG versus placebo had a One day after initiation of probiot-

junctions between epithelial cells and shorter mean ± S.D. duration of diar- ics, children who were given LGG

decreasing intestinal permeability.7 rhea (58.3 ± 27.6 hours versus 71.9 ± or the probiotic mixture also had a

Another proposed mechanism of 35.8 hours, p = 0.03) and a shorter significantly lower daily stool output

action of probiotics involves immu- hospital stay (78.8 ± 22.2 hours ver- compared with the other groups (p <

nomodulation. Animal studies have sus 96.3 ± 21.4 hours, p = 0.04). In 0.001). The other three preparations

found that some probiotic strains addition, patients treated with LGG (S. boulardii, Bacillus clausii, and

augment the immune response by were less likely to have persistent Enterococcus faecium SF 68) did not

stimulating the phagocytic activity diarrhea (i.e., diarrhea lasting longer significantly affect the duration and

of lymphocytes and macrophages.18 than seven days) (2.7% versus 10.7% severity of diarrhea.

Probiotics also increase immuno- of those receiving placebo, p < 0.01).

globulin A (IgA) and stimulate cy- Van Niel et al. 26 conducted a AAD and C. difficile infection

tokine production by mononuclear meta-analysis of nine clinical trials There is evidence that probiotics

cells.15,18 Kaila et al.23 found that (n = 765) involving children younger can prevent AAD and treat C. difficile

children with acute rotaviral diar- than three years with acute infectious infection (CDI); however, data are

rhea who were given Lactobacillus diarrhea who received Lactobacillus conflicting or inconclusive.2,5,13,14,17

rhamnosus strain GG (LGG) had an species, most frequently LGG. The The most common probiotic mi-

increased IgA, immunoglobulin G, studies examined were random- croorganisms used for these diseases

and immunoglobulin M response, ized, blinded, controlled trials that include lactobacilli and S. boular-

resulting in a shortened duration of measured diarrhea duration and the dii.5 Two meta-analyses of studies

gastroenteritis symptoms. frequency of diarrheal stools on the examining the use of probiotics to

Numerous health effects are as- second day of treatment. The meta- prevent AAD suggested that concur-

sociated with probiotic use. While analysis revealed a reduced mean rent administration of probiotics

some of these indications are well duration of diarrhea by 0.7 day (95% (most commonly lactobacilli and

documented, probiotics are often confidence interval [CI], 0.3–1.2 S. boulardii) with antibiotics re-

used to treat conditions for which days) and a decrease in diarrhea fre- sulted in a reduced frequency of

data regarding the efficacy of probi- quency by a mean of 1.6 stools per diarrhea.28,29 The first meta-analysis,

otics are lacking or conflicting.3,9,24 day on day 2 of treatment (95% CI, which examined 7 trials (n = 881),

This article focuses on the more- 0.7–2.6 fewer stools) in children who revealed a combined relative risk

common uses of probiotics. received probiotics. (RR) of 0.3966 (95% CI, 0.27–0.57)

All probiotics are not equally ef- in favor of a beneficial effect of

Acute diarrhea fective in treating acute diarrhea in probiotics for reducing the risk of

There is convincing evidence from children. Canani et al.27 illustrated AAD. 28 The other meta-analysis

multiple studies supporting the ef- this point and emphasized that the yielded a combined odds ratio of

ficacy of probiotics in the treatment particular probiotic preparation 0.37 (95% CI, 0.26–0.53; p < 0.001)

of acute diarrhea, especially in chil- should be chosen based on solid effi- for pooled data from all 9 trials

dren with rotavirus infection. The cacy data. In their study, 571 children (n = 1214), supporting probiotic

probiotics most frequently studied age 3–36 months with acute diarrhea treatment over placebo in the pre-

for treating acute diarrhea include were randomized to one of six differ- vention of AAD.29

LGG and Lactobacillus reuteri.2,7,15,17 ent treatment groups: oral rehydra- A third meta-analysis reviewed

The European Society for Pediatric tion solution alone (control group) 25 randomized controlled trials (n =

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and or one of five probiotic preparations, 2810) examining the use of probiot-

Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010 451

clinical review Probiotics

ics for the prevention of AAD and ized 245 American tourists traveling probiotics (most commonly lacto-

6 randomized controlled trials (n to various developing countries to re- bacilli and bifidobacteria) improved

= 354) of probiotic therapy for the ceive LGG or placebo. Those travelers global IBS symptoms (RRpooled, 0.77;

treatment or prevention of CDI.30 who ingested LGG had a mean daily 95% CI, 0.62–0.94) and reduced ab-

The meta-analysis revealed that LGG, risk of developing diarrhea of 3.9%, dominal pain (RRpooled, 0.78; 95% CI,

S. boulardii, and various mixtures of compared with 7.4% for travelers 0.69–0.88) compared with placebo.38

two probiotic strains significantly taking placebo (p = 0.05). In contrast, This meta-analysis was not able to

reduced the frequency of AAD. How- Katelaris et al.35 found that ingestion examine other types of individual IBS

ever, only S. boulardii in combination of L. acidophilus or Lactobacillus fer- symptoms (e.g., bloating or disten-

with oral vancomycin or metronida- mentum strain KLD did not reduce sion, flatulence, stool frequency) or

zole or both significantly decreased the frequency of diarrhea among 282 the effectiveness of specific probiotic

the recurrence of CDI. Other pro- British soldiers deployed to Belize. strains due to insufficient data. A re-

biotics tested, including LGG and McFarland 36 conducted a meta- view of 14 clinical trials also revealed

Lactobacillus plantarum 299v in analysis of 12 studies (n = 4709), that probiotics (most commonly lac-

combination with oral vancomycin which included the two above- tobacilli, bifidobacteria, and VSL#3)

or metronidazole, were not effective mentioned studies,34,35 on the role improved overall symptoms associat-

in decreasing CDI recurrence rates. of probiotics in the prevention of ed with IBS compared with placebo;

On the other hand, a recent study travelers’ diarrhea. The types of pro- however, the contributing studies

found that the rate of C. difficile colo- biotics in the meta-analysis included had methodological limitations.37 Al-

nization in 44 critically ill patients S. boulardii (4 studies), various types though probiotics may be beneficial

receiving antibiotics was significantly of lactobacilli (6 studies), and probi- in treating IBS symptoms, limita-

reduced by enteral administration otic mixtures (2 studies). The meta- tions exist in interpreting trial results

of L. plantarum 299v (p < 0.05).31 It analysis revealed that probiotics due to the lack of standardization of

is important to note that this study significantly prevented travelers’ di- strains, dosages, treatment durations,

was stopped prematurely due to the arrhea (pooled relative risk [RRpooled], and assessment of clinical outcomes.

low rate of enrollment and reduced 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79–0.91; p < 0.001). More data are needed before probiot-

funding. ics can be recommended as typical

In contrast to the previous studies IBS care in the treatment of IBS.37,38

that found that probiotics reduced IBS is characterized by abdominal

the rate of CDI, a systematic review pain, bloating, flatulence, and altered Inflammatory bowel disease

of 8 randomized controlled trials bowel habits. These symptoms may Inf lammatory diseases of the

did not find sufficient evidence for be due to bacterial overgrowth in digestive tract include UC, Crohn’s

routine probiotic use in CDI.32 A the small intestine, causing increased disease, and pouchitis. An im-

Cochrane Library review also con- fermentation activities and gas pro- balance of intestinal microf lora,

cluded that there was inadequate ev- duction.37 Some studies suggest that specifically high numbers of en-

idence to support the adjunctive use probiotics may be beneficial in re- teroadhesive and enterohemorrhagic

of probiotics for CDI.33 While results ducing bloating and flatulence asso- E. coli with UC and reduced levels of

have been inconsistent, some stud- ciated with IBS. The probiotics used bifidobacteria with Crohn’s disease,

ies have indicated that probiotics, most frequently in the treatment of may contribute to the inflammation

especially S. boulardii, may prevent IBS include lactobacilli and bifido- seen with these diseases. Probiotics

C. difficile overgrowth and decrease bacteria. In addition, a combination may improve the microbial balance

CDI recurrence. product (VSL#3, VSL Pharmaceuti- of the indigenous flora. Although

cals, Inc., Towson, MD) has reduced studies have been conflicting, probi-

Travelers’ diarrhea abdominal bloating and flatulence. otics seem to be an attractive option

Results of studies evaluating the This preparation contains eight bac- in the treatment and prevention of

effectiveness of probiotics for pre- terial organisms in large numbers: inflammatory bowel disease, provid-

venting travelers’ diarrhea have three bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium ing an appealing alternative to the

been inconsistent, possibly due to longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, and use of antibiotics.5,7

the probiotic strain used and the Bifidobacterium breve), four lactoba- Several studies examining the role

various trip destinations. Similar to cilli (L. acidophilus, Lactobacillus ca- of probiotics in UC have suggested

AAD and CDI, the most commonly sei, L. bulgaricus, and L. plantarum), that they can induce or maintain

studied probiotics for travelers’ and S. thermophilus.12,24 disease remission. Three controlled

diarrhea include lactobacilli and A recent meta-analysis involv- trials compared the probiotic E. coli

S. boulardii.5,8 Hilton et al.34 random- ing 20 trials (n = 1404) found that Nissle 1917 with mesalamine in UC

452 Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010

clinical review Probiotics

and found that the two therapies found that a six-month regimen of for one year or until relapse. Similar

were similar in preventing disease Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 was not to the previous study, 17 of the 20 pa-

relapse, suggesting that the probiotic effective in preventing endoscopic tients treated with VSL#3 remained

was equivalent to standard therapy recurrence of Crohn’s disease after in remission at one year versus only

with mesalamine in maintaining surgical resection. 1 of 16 patients who received placebo

remission.39-41 Two of the studies Various studies support the use (p < 0.0001). In addition to pre-

had notable limitations—diverse of probiotics, particularly VSL#3, in venting relapses, Gionchetti et al.47

patient population39 and short study reducing relapse rates and maintain- showed that the probiotic mixture

duration 40—but the more recent ing remission of pouchitis. Pouchitis VSL#3 was significantly more effec-

study was methodologically more is a nonspecific inflammation of tive than placebo in preventing the

sound and confirmed the results of the ileal reservoir, which is formed occurrence of pouchitis (p < 0.05)

the other two studies.41 The particu- surgically after an ileal pouch–anal during the first year after pouch for-

lar nonpathogenic E. coli probiotic anastomosis from a proctocolec- mation in this randomized, double-

strain used in these three studies has tomy. It is characterized by increased blind, placebo-controlled study in-

been shown to colonize the intestine stool frequency and abdominal volving 40 patients.

and antagonize the pathogenic bac- cramping.46-48 Although the etiology In contrast to those studies with

teria seen with UC.40 Another study of pouchitis is unknown, it may be encouraging results using VSL#3 in

investigated the use of S. boulardii in associated with decreased lactobacilli pouchitis, a three-month trial involv-

25 patients who developed a mild- and bifidobacteria counts as well as ing LGG did not show any benefit as

to-moderate clinical flare-up of UC increased concentrations of other primary therapy for ileal pouch in-

while taking standard maintenance bacteria.46 In addition to modifying flammation.49 This trial did not show

therapy with mesalamine.42 For vari- the endogenous flora, VSL#3 alters differences in the mean pouchitis

ous reasons, treatment with corticos- the immune response in pouchitis disease activity index scores between

teroids was not suitable for these pa- by raising tissue levels of the antiin- treatment with LGG and placebo,

tients. Clinical remission, confirmed flammatory cytokine interleukin 10 and only 40% of patients who re-

endoscopically, was attained in 68% and reducing tissue levels of tumor ceived the probiotic had LGG recov-

of patients after adding a four-week necrosis factor a, interferon g, and ered in their fecal flora.

course of S. boulardii to mesalamine matrix metalloproteinase activity.47,48

treatment. This study was limited by In a randomized, double-blind, Allergy

its small sample size, lack of a con- placebo-controlled trial involving Several studies have found that

trol group, and open-label design. 40 patients with chronic relapsing probiotics have a beneficial effect on

Bibiloni et al.43 noted that a six-week pouchitis, Gionchetti et al.46 found atopic eczema. Kalliomaki et al.50 con-

course of VSL#3 was also effective in that VSL#3 was significantly more ducted a double-blind, randomized,

inducing remission or causing a re- effective than placebo in maintaining placebo-controlled trial in which 159

sponse in 77% of patients with active remission after nine months. All 20 pregnant women with a family his-

mild-to-moderate UC that was un- placebo-treated patients experienced tory of atopic disease were given LGG

responsive to conventional therapy. a relapse within four months, while or placebo daily for two to four weeks

This open-label trial also lacked a 17 of the 20 patients treated with before their expected delivery date,

control group and involved only 34 VSL#3 remained in remission after followed by administration of the

patients. nine months (p < 0.001). When the probiotic or placebo to the newborn

Studies have also investigated probiotic was discontinued at the infant for 6 months; 132 participants

the role of probiotics in maintain- study’s end, these 17 patients also completed the trial. There was a 50%

ing remission of Crohn’s disease. experienced relapse within four reduction in the frequency of atopic

Guslandi et al.44 noted that patients months. In addition, fecal concentra- eczema during the first two years

with inactive Crohn’s disease had a tions of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, of the children’s lives in those given

significantly lower clinical relapse and S. thermophilus increased signifi- probiotics compared with placebo

rate when receiving a six-month cantly from baseline in patients treat- (23% [15 of 64] versus 46% [31 of

regimen of S. boulardii plus me- ed with VSL#3 (p < 0.001). Mimura et 68]; RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.32–0.84; p =

salamine versus treatment with me- al.48 confirmed the efficacy of VSL#3 0.008). This cohort was reexamined

salamine alone (6.25% versus 37.5%, in maintaining remission in patients after four years, and significantly

p = 0.04), suggesting that the pro- with recurrent or refractory pouchi- fewer children who had previously

biotic yeast may be beneficial in the tis. In this study, 36 patients whose received LGG were diagnosed with

maintenance treatment of Crohn’s pouchitis was in remission were ran- atopic eczema compared with pla-

disease. In contrast, Marteau et al.45 domized to receive VSL#3 or placebo cebo (26% [14 of 53] versus 46% [25

Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010 453

clinical review Probiotics

of 54]; RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33–0.97), ly for 14 days. Within one week, one ity, and purity of the bacteria or

suggesting that the protective effect or both of the Lactobaccillus strains yeast in probiotics can vary among

of this probiotic on atopic eczema were recovered from the vaginas of products due to the complexity of

in at-risk children continues beyond all 10 women, and no VVC occurred quality control with live microor-

infancy. 51 In another randomized during the study. Hilton et al.56 found ganisms and the lack of universal

double-blind study, 27 infants (mean that consumption of 8 oz of yogurt quality-assurance programs. 13,38,57

age, 4.6 months) with atopic eczema containing L. acidophilus daily for six One study analyzed 18 commercially

received formula supplemented with months reduced vaginal colonization available probiotic products available

probiotics (either LGG or Bifido- and infection by Candida species in in the United States and found that

bacterium lactis Bb-12) or the same a crossover trial involving 33 women 7 (39%) had differences between the

formula without probiotics.52 After 2 with recurrent VVC, 13 of whom stated and actual concentrations of

months, the Scoring Atopic Derma- completed the protocol. The mean bacteria.61

titis index, which reflects the extent number of candidal infections of Probiotic dosing varies depending

and severity of atopic eczema, was the vagina and candidal coloniza- on the product and specific indica-

reduced significantly in the infants tion in the vagina and rectum were tion. No consensus exists about the

given probiotic-supplemented for- significantly lower in the women minimum number of microorgan-

mulas compared with those who did who consumed yogurt versus the isms that must be ingested to ob-

not receive probiotic supplementa- control group (0.38 versus 2.54, p = tain a beneficial effect.16 Typically,

tion (p = 0.002). 0.001 and 0.84 versus 3.23, p = 0.001, a probiotic should contain several

respectively). However, these three billion microorganisms to increase

Genitourinary infections studies had important methodologi- the likelihood of adequate gut colo-

Abnormal vaginal microbiota cal limitations, including small sam- nization.28 For lactobacilli, typical

may lead to symptomatic infections, ple sizes, inadequate controls, and doses used in studies ranged from

including vulvovaginal candidiasis lack of blinding. Two of the studies 1–20 billion colony-forming units

(VVC). Lactobacilli, especially Lac- lacked detailed statistical analyses,54,55 per day. For S. boulardii, most studies

tobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus one study had a high attrition rate,56 examined daily doses ranging from

iners, are the predominant vaginal and more than half of the women in 250 to 500 mg.57 Table 2 summarizes

microorganisms in healthy premeno- one study had recently completed dosing for various probiotic strains

pausal women. When the normal treatment with antifungal medica- based on doses found to be effica-

vaginal microflora is disrupted, such tions.54 Therefore, it is difficult to cious in human studies. Products

as with use of broad-spectrum anti- reliably conclude whether probiotics should be stored according to the

biotics, overgrowth of Candida albi- can prevent recurrent VVC. manufacturer’s recommendations,

cans may occur, causing VVC. Restor- since some may require refrigeration.

ing the normal flora with lactobacilli Dosages and product selection In addition, preparations may have a

may help treat this genital infection.53 Probiotics are available as supple- limited shelf life, and many prepara-

Hilton et al.54 conducted a study in- ments (i.e., tablets, capsules, or tions contain several different spe-

volving 28 women with a history of powders) and as fermented dairy cies, so dosing may vary depending

recurrent VVC who also had signs products (i.e., yogurt and milk). on the product.

and symptoms of active VVC. After Their efficacy relies on their ability to Various probiotics are available in

the administration of vaginal sup- survive passage through the gastro- the United States; however, only those

positories containing LGG twice intestinal tract and colonize a tissue products that have been evaluated in

daily for seven days, all of the women section. To prevent destruction by controlled human studies should be

reported an improvement in vagi- gastric acid and intestinal bile salts, recommended. Some examples of

nal symptoms and reduced vaginal some probiotic preparations may be these commercially available prepa-

erythema and discharge. Reid et al.55 enteric coated or microencapsulated. rations include LGG (Culturelle,

investigated the ability of an orally For colonization to occur, probiotics Amerifit Brands, Fairfield, NJ),

administered solution containing must contain living, viable organisms S. boulardii (Florastor, Biocodex, Inc.,

L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. fermentum and must be ingested on a regular Beauvais, France), B. infantis 35624

RC-14 to colonize the vagina in 10 basis in order to maintain effective (Align, JB Laboratories, Holland,

women who were asymptomatic for concentrations.57-60 Unfortunately, MI), and VSL#3.62 Yogurt products

infection but who had a history of the manufacturing process may fermented with probiotics should

recurrent urogenital infections, pri- cause living organisms to become be labeled with a “Live and Active

marily recurrent VVC. The probiotic nonviable, thus reducing probiotic Cultures” seal, specifying that the

solution was administered twice dai- effectiveness.32 The quantity, qual- preparation contains a minimum

454 Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010

clinical review Probiotics

of 100 million viable bacteria per keted by Dannon/Danone as “Bifidus are generally considered safe and

gram at the time of manufacture. An regularis.”57,62,63 well tolerated. The most common

example is Activia yogurt (Dannon/ adverse effects include bloating

Danone, Paris, France), which con- Adverse effects and safety and flatulence; however, these are

tains B. animalis DN-173 010, mar- When ingested orally, probiotics typically mild and subside with con-

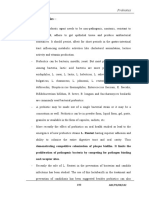

Table 2.

Probiotic Species and Dosinga

Indication and Probiotic Recommended Dosage Regimen

Acute infectious diarrhea in infants and

children

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) At least 1010 CFU in 250 mL of oral rehydration solution25; 1010–1011 CFU twice daily for

2–5 days26

Lactobacillus reuteri 10 –1011 CFU daily up to 5 days26

10

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea

Saccharomyces boulardii 4 × 109–2 × 1010 CFU daily for 1–4 wk30

LGG 6 × 109–4 × 1010 CFU daily for 1–2 wk30

Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus 2 × 109 CFU daily for 5–10 days30

bulgaricus

L. acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum 5 × 109 CFU daily for 7 days30

L. acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis 1 × 1011 CFU daily for 21 days30

Clostridium difficile infection

S. boulardii 2 × 1010 CFU (1 g) daily for 4 wk plus vancomycin and/or metronidazole30

Travelers’ diarrhea

LGG 2 × 109 bacteria daily starting 2 days before departure and continued throughout

trip34

S. boulardii 5 × 109–2 × 1010 CFU daily starting 5 days before departure and continued

throughout trip36

Irritable bowel syndrome

VSL#3b 9 × 1011 CFU daily for 8 wk38

Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 106–1010 CFU daily for 4 wk38

LGG and other organisms 8–9 × 109 CFU daily for 6 mo24,38

Ulcerative colitis (UC)

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 Active UC: 5 × 1010 bacteria twice daily until remission (maximum of 12 wk), followed

by 5 × 1010 bacteria daily for a maximum of 12 mo39; inactive UC: 5 × 1010 bacteria

daily (study duration was 12 wk)40

S. boulardii Active UC: 250 mg 3 times daily for 4 wk plus mesalamine42

VSL#3b Active UC: 1.8 × 1012 bacteria (two 3-g sachets) twice daily for 6 wk plus conventional

therapy43

Crohn’s disease

S. boulardii Maintenance therapy: 1 g daily for 6 mo plus mesalamine44

Pouchitis

VSL#3b Maintenance therapy: 1.8 × 1012 bacteria daily, given as 3-g sachets twice daily (study

duration was 9 mo)46; maintenance therapy: 1.8 × 1012 bacteria daily, given as two

3-g sachets once daily (study duration was 12 mo)48

Atopic disease prevention

LGG 1010 CFU daily for 2–4 wk before expected delivery in pregnant women, followed by

infant administration for 6 mo50

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

LGG 109 bacteria per suppository inserted twice daily for 7 days54

L. rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus At least 109 bacteria suspended in skim milk given orally twice daily for 14 days55

fermentum RC-14

L. acidophilus 8 oz yogurt containing ≥108 CFU/mL ingested daily for 6 mo56

a

CFU = colony-forming units.

b

VSL#3 is a mixture of eight probiotic organisms (Lactobacillus casei, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, B. longum, Bifidobacterium breve, B. infantis, and

Streptococcus thermophilus).

Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010 455

clinical review Probiotics

tinued use.24,57,58 Constipation and species.69 Fortunately, most cases of course and putting them at risk for

increased thirst have also rarely been probiotic bacteremia or fungemia developing infectious complications,

associated with S. boulardii.64 One have responded well to appropriate including infected pancreatic necro-

theoretical concern associated with antibiotic or antifungal therapy. sis. This multicenter, randomized,

probiotics includes the potential for In a review of the literature, Boyle double-blind, placebo-controlled

these viable organisms to move from et al.69 identified major and minor trial involved 298 patients who

the gastointestinal tract and cause risk factors for probiotic-associated received a multispecies probiotic

systemic infections. Although rare, sepsis. Major risk factors included preparation (L. acidophilus, L. casei,

probiotic-related bacteremia and immunosuppression (including a Lactobacillus salivarius, Lactobacillus

fungemia have been reported.65 It is debilitated state or malignancy) and lactis, B. bifidum, and B. lactis) or

estimated that the risk of developing prematurity in infants. Minor risk placebo, administered enterally twice

bacteremia from ingested lactobacilli factors were the presence of a central daily for a maximum of 28 days. The

probiotics is less than 1 per 1 million venous catheter, impairment of the study found that this combination of

users,66 and the risk of developing intestinal epithelial barrier (such as six probiotic strains did not decrease

fungemia from S. boulardii is esti- with diarrheal illness), cardiac valvu- infectious complications in patients

mated at 1 per 5.6 million users.64 lar disease (Lactobacillus probiotics with predicted severe acute pancrea-

Another theoretical risk associated only), concurrent administration titis but rather was associated with

with probiotics involves the possible with broad-spectrum antibiotics to significantly more deaths than was

transfer of antibiotic resistance from which the probiotic is resistant, and placebo (24 versus 9, p = 0.01) and

probiotic strains to pathogenic bac- administration of probiotics via a an increased risk of bowel ischemia in

teria; however, this has not yet been jejunostomy tube (this method of the probiotics group compared with

observed.65,66 delivery could increase the number placebo (9 versus 0, p = 0.004). The

Although no serious adverse of viable probiotic organisms reach- authors stated that probiotics should

events have been described in clinical ing the intestine by bypassing the not be routinely given to patients with

trials, systemic infections associated acidic contents of the stomach). The predicted severe acute pancreatitis and

with specific probiotics have been authors recommended that probiot- should be used cautiously in critically

noted in isolated reports. These in- ics be used cautiously in patients ill patients or those at risk for nonoc-

clude sepsis or endocarditis with lac- with one major risk factor or more clusive mesenteric ischemia.

tobacilli, fungemia with S. boulardii, than one minor risk factor.

and liver abscess with LGG.24,65 Bac- It is important to remember that Drug interactions

teremia due to lactobacilli rarely oc- the overall risk of developing an Since probiotics contain live mi-

curs, but predisposing factors include infection from ingested probiotics croorganisms, concurrent admin-

immunosuppression, prior hospi- is very low, particularly when used istration of antibiotics could kill

talization, severe underlying comor- by generally healthy individuals. In a large number of the organisms,

bidities, previous antibiotic therapy, Finland, LGG has been routinely reducing the efficacy of the Lacto-

and prior surgical interventions.67 added to dairy products since 1990.70 bacillus and Bifidobacterium species.

There have been several documented Despite a substantial increase in the Patients should be instructed to

cases of fungemia associated with consumption of LGG-containing separate administration of antibi-

use of S. boulardii. Those at greatest products from 1995 through 2000, otics from these bacteria-derived

risk include critically ill or highly im- there was no significant change in the probiotics by at least two hours.58,72

munocompromised patients or those incidence of Lactobacillus-associated Similarly, S. boulardii might interact

with central venous catheters in bacteremia observed during the sur- with antifungals, reducing the ef-

place. When S. boulardii capsules are veillance period of 1990–2000. ficacy of this probiotic.73 According

opened at the bedside for adminis- A recent study found an increased to the manufacturer, Florastor, which

tration through the nasogastric tube, risk of mortality when probiot- contains S. boulardii, should not be

central venous catheters may become ics were used to prevent infectious taken with any oral systemic antifun-

contaminated and serve as the source complications in patients with pre- gal products.74 Probiotics should also

of entry for the organism.68 Although dicted severe acute pancreatitis.71 be used cautiously in patients taking

there have been infrequent reports These patients had acute pancrea- immunosuppressants, such as cy-

of lactobacillemia and fungemia, to titis and an elevated Acute Physiol- closporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine,

date there have been no reports of ogy and Chronic Health Evaluation and chemotherapeutic agents, since

bifidobacterial sepsis associated with (APACHE) II score, Imrie/modified probiotics could cause an infection

the use of a probiotic, supporting the Glasgow score, or C-reactive protein or pathogenic colonization in immu-

low pathogenicity of bifidobacteria value, predicting a severe disease nocompromised patients.58,72,73

456 Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010

clinical review Probiotics

Precautions and contraindications provided. Future research needs to ium difficile-associated diarrhea, and

recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated

Since probiotics contain live mi- encompass more well-designed clini- diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;

croorganisms, there is a slight chance cal trials in larger populations and 42(suppl 2):S64-70.

that these preparations might cause for longer durations to better evalu- 14. MacIntyre A, Cymet TC. Probiotics: the

benefits of bacterial cultures. Compr Ther.

pathological infection, particularly in ate the efficacy of probiotics. 2005; 31:181-5.

critically ill or severely immunocom- 15. Scarpellini E, Cazzato A, Lauritano C et

promised patients. Probiotic strains Conclusion al. Probiotics: which and when? Dig Dis.

2008; 26:175-82.

of Lactobacillus have also been re- Probiotics have demonstrated 16. Farnworth ER. The evidence to support

ported to cause bacteremia in patients efficacy in preventing and treating health claims for probiotics. J Nutr. 2008;

with short-bowel syndrome, possibly various medical conditions, particu- 138(suppl):1250S-4S.

17. Goldin BR, Gorbach SL. Clinical indica-

due to altered gut integrity.57,58,72,73 larly those involving the gastroin- tions for probiotics: an overview. Clin

Caution is also warranted in patients testinal tract. Data supporting their Infect Dis. 2008; 46(suppl 2):S96-100.

with central venous catheters, since role in other conditions are often 18. Reid G, Jass J, Sebulsky MT et al. Potential

uses of probiotics in clinical practice. Clin

contamination leading to fungemia conflicting. Microbiol Rev. 2003; 16:658-72.

has been reported when Saccharomy- 19. Silva M, Jacobus NV, Deneke C et al.

ces capsules were opened and admin- References Antimicrobial substance from a human

1. Guidelines for the evaluation of probiot- Lactobacillus strain. Antimicrob Agents

istered at the bedside.68,73 ics in food: report of a Joint FAO/WHO Chemother. 1987; 31:1231-3.

Lactobacillus preparations are Working Group. London, Ontario, Can- 20. Castagliuolo I, Riegler MF, Valenick L

contraindicated in persons with a ada: Food and Agriculture Organization et al. Saccharomyces boulardii protease

of the United Nations and World Health inhibits the effects of Clostridium difficile

hypersensitivity to lactose or milk.75 Organization; 2002. toxins A and B in human colonic mucosa.

S. boulardii is contraindicated in 2. Senok AC, Ismaeel AY, Botta GA. Probiot- Infect Immun. 1999; 67:302-7.

patients with a yeast allergy.73,76 No ics: facts and myths. Clin Microbiol Infect. 21. Chan RC, Reid G, Irvin RT et al. Com-

2005; 11:958-66. petitive exclusion of uropathogens from

contraindications are listed for 3. Schrezenmeir J, de Vrese M. Probiotics, human uroepithelial cells by Lactobacillus

bifidobacteria, since most species prebiotics, and synbiotics—approaching whole cells and cell wall fragments. Infect

are considered nonpathogenic and a definition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001; Immun. 1985; 47:84-9.

73(suppl):361S-364S. 22. Mack DR, Michail S, Wei S et al. Probiot-

nontoxigenic.57,72 4. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert ics inhibit enteropathogenic E. coli adher-

Consultation on evaluation of health ence in vitro by inducing intestinal mucin

Limitations and nutritional properties of probiotics gene expression. Am J Physiol. 1999;

in food including powder milk with live 276:G941-50.

Probiotics are regulated as dietary lactic acid bacteria. Cordoba, Argentina: 23. Kaila M, Isolauri E, Soppi E et al. En-

supplements and not subjected Food and Agriculture Organization of hancement of the circulating antibody

to the same rigorous standards as the United Nations and World Health secreting cell response in human diarrhea

Organization; 2001. by a human Lactobacillus strain. Pediatr

medications. A challenge with these 5. Santosa S, Farnworth E, Jones PJ. Probiot- Res. 1992; 32:141-4.

products involves the complexity of ics and their potential health claims. Nutr 24. Probiotics. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2007;

quality control with live microorgan- Rev. 2006; 64:265-74. 49:66-8.

6. Alvarez-Olmos MI, Oberhelman RA. 25. Guandalini S, Pensabene L, Zikri MA et

isms. As a result, individuals may Probiotic agents and infectious diseases: al. Lactobacillus GG administered in oral

obtain a product that is ineffective a modern perspective on a traditional rehydration solution to children with

or that contains varying quantities therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 32:1567- acute diarrhea: a multicenter European

76. trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;

of bacteria or yeast. Published stud- 7. Doron S, Gorbach SL. Probiotics: their 30:54-60.

ies involving probiotics have often role in the treatment and prevention of 26. Van Niel CW, Feudtner C, Garrison

utilized small sample sizes and lacked disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006; MM et al. Lactobacillus therapy for acute

4:261-75. infectious diarrhea in children: a meta-

appropriate randomization, blind- 8. Pham M, Lemberg DA, Day AS. Probiot- analysis. Pediatrics. 2002; 109:678-84.

ing, or control groups. Therefore, the ics: sorting the evidence from the myths. 27. Canani RB, Cirillo P, Terrin G et al. Pro-

results from many probiotic studies Med J Aust. 2008; 188:304-8. biotics for treatment of acute diarrhoea

9. Vanderhoof JA, Young R. Probiotics in in children: randomised clinical trial of

should be interpreted cautiously due the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; five different preparations. BMJ. 2007;

to methodological limitations. There 46(suppl 2):S67-72. 335:340-2.

is also heterogeneity among stud- 10. Vanderhoof JA, Young RJ. Current and 28. Cremonini F, Di Caro S, Nista EC et al.

potential uses of probiotics. Ann Allergy Meta-analysis: the effect of probiotic

ies, since different probiotic doses, Asthma Immunol. 2004; 93(suppl 3):S33- administration on antibiotic-associated

strains, treatment durations, and 7. diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;

patient populations may have been 11. Goldin BR. Health benefits of probiotics. 16:1461-7.

Br J Nutr. 1998; 80(suppl 2):S203-7. 29. D’Souza AL, Rajkumar C, Cooke J et al.

used. Since probiotic effects are spe- 12. Wald A, Rakel D. Behavioral and comple- Probiotics in prevention of antibiotic as-

cific to a particular strain, this may mentary approaches for the treatment sociated diarrhoea: meta-analysis. BMJ.

have important implications when of irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin 2002; 324:1361-6.

Pract. 2008; 23:284-92. 30. McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiot-

interpreting meta-analyses, particu- 13. Surawicz CM. Role of probiotics in ics for the prevention of antibiotic as-

larly if strain designations were not antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Clostrid- sociated diarrhea and the treatment of

Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010 457

clinical review Probiotics

Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastro- for prophylaxis of postoperative recur- potential applications. Curr Issues Intest

enterol. 2006; 101:812-22. rence in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, Microbiol. 2002; 3:39-48.

31. Klarin B, Wullt M, Palmquist I et al. Lac- double blind, placebo controlled GETAID 61. Katz JA, Pirovano F, Matteuzzi D et al.

tobacillus plantarum 299v reduces coloni- trial. Gut. 2006; 55:842-7. Commercially available probiotic prepa-

sation of Clostridium difficile in critically 46. Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A et al. rations: are you getting what you pay

ill patients treated with antibiotics. Acta Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance for? Gastroenterology. 2002; 122(suppl 1):

Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008; 52:1096-102. treatment in patients with chronic A-459. Abstract.

32. Dendukuri N, Costa V, McGregor M et pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo- 62. Sanders ME. Probiotics: background

al. Probiotic therapy for the prevention controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000; and product table. www.usprobiotics.org

and treatment of Clostridium difficile- 119:305-9. (accessed 2009 Mar 23).

associated diarrhea: a systematic review. 47. Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Helwig U et al. 63. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Da-

CMAJ. 2005; 173:167-70. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with pro- tabase. Yogurt monograph. www.natural

33. Pillai A, Nelson RL. Probiotics for treat- biotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo- database.com (accessed 2009 Mar 23).

ment of Clostridium difficile-associated controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003; 64. Karpa KD. Probiotics for Clostridium dif-

colitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst 124:1202-9. ficile diarrhea: putting it into perspective.

Rev. 2008; 1:CD004611. 48. Mimura T, Rizzello F, Helwig U et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2007; 41:1284-7.

34. Hilton E, Kolakowski P, Singer C et al. Once daily high dose probiotic therapy 65. Snydman DR. The safety of probiotics.

Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG as a diarrheal (VSL#3) for maintaining remission in Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46(suppl 2):S104-

preventive in travelers. J Travel Med. 1997; recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Gut. 11.

4:41-3. 2004; 53:108-14. 66. Borriello SP, Hammes WP, Holzapfel W

35. Katelaris PH, Salam I, Farthing MJ. Lac- 49. Kuisma J, Mentula S, Jarvinen H et al. et al. Safety of probiotics that contain

tobacilli to prevent traveler’s diarrhea? N Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG on lactobacilli or bifidobacteria. Clin Infect

Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1360-1. Letter. ileal pouch inflammation and micro- Dis. 2003; 36:775-80.

36. McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics bial flora. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 67. Salminen MK, Rautelin H, Tynkkynen

for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea. 17:509-15. S et al. Lactobacillus bacteremia, clinical

Travel Med Infect Dis. 2007; 5:97-105. 50. Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Arvilommi significance, and patient outcome, with

37. Wilhelm SM, Brubaker CM, Varcak EA H et al. Probiotics in primary prevention special focus on probiotic L. rhamnosus

et al. Effectiveness of probiotics in the of atopic disease: a randomised placebo- GG. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38:62-9.

treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. controlled trial. Lancet. 2001; 357:1076-9. 68. Munoz P, Bouza E, Cuenca-Estrella M et

Pharmacotherapy. 2008; 28:496-505. 51. Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Poussa T et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia: an

38. McFarland LV, Dublin S. Meta-analysis of al. Probiotics and prevention of atopic emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect

probiotics for the treatment of irritable disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomised Dis. 2005; 40:1625-34.

bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003; 69. Boyle RJ, Robins-Browne RM, Tang ML.

2008; 14:2650-61. 361:1869-71. Probiotic use in clinical practice: what are

39. Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey 52. Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sutas Y et al. Probiot- the risks? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006; 83:1256-

PM et al. Non-pathogenic Escherichia ics in the management of atopic eczema. 64.

coli versus mesalazine for the treatment Clin Exp Allergy. 2000; 30:1604-10. 70. Salminen MK, Tynkkynen S, Rautelin H

of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. 53. Reid G, Bruce AW. Urogenital infections et al. Lactobacillus bacteremia during a

Lancet. 1999; 354:635-9. in women: can probiotics help? Postgrad rapid increase in probiotic use of Lacto-

40. Kruis W, Schutz E, Fric P et al. Double- Med J. 2003; 79:428-32. bacillus rhamnosus GG in Finland. Clin

blind comparison of an oral Escherichia 54. Hilton E, Rindos P, Isenberg HD. Lac- Infect Dis. 2002; 35:1155-60.

coli preparation and mesalazine in main- tobacillus GG vaginal suppositories and 71. Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Bus-

taining remission of ulcerative colitis. vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:1433. kens E et al. Probiotic prophylaxis in

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997; 11:853-8. Letter. predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a

41. Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J et al. Main- 55. Reid G, Bruce AW, Fraser N et al. Oral randomised, double-blind, placebo-

taining remission of ulcerative colitis probiotics can resolve urogenital infec- controlled trial. Lancet. 2008; 371:651-9.

with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle tions. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 72. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Da-

1917 is as effective as with standard me- 2001; 30:49-52. tabase. Bifidobacteria monograph. www.

salazine. Gut. 2004; 53:1617-23. 56. Hilton E, Isenberg HD, Alperstein P et naturaldatabase.com (accessed 2009 Mar

42. Guslandi M, Giollo P, Testoni PA. A pilot al. Ingestion of yogurt containing Lac- 23).

trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in ulcer- tobacillus acidophilus as prophylaxis for 73. Natural Medicines Comprehensive

ative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. candidal vaginitis. Ann Intern Med. 1992; Database. Saccharomyces boulardii

2003; 15:697-8. 116:353-7. monograph. www.naturaldatabase.com

43. Bibiloni R, Fedorak RN, Tannock GW 57. Kligler B, Cohrssen A. Probiotics. Am (accessed 2009 Mar 23).

et al. VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces Fam Physician. 2008; 78:1073-8. 74. Florastor (Saccharomyces boulardii lyo)

remission in patients with active ulcer- 58. Natural Medicines Comprehensive package insert. Beauvais, France: Bioco-

ative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; Database. Lactobacillus monograph. dex; 2005-09.

100:1539-46. www.naturaldatabase.com (accessed 75. Drugdex System. Lactobacillus mono-

44. Guslandi M, Mezzi G, Sorghi M et al. 2009 Mar 23). graph. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson

Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance 59. Sutton A. Product development of probi- Micromedex (accessed 2009 Mar 23).

treatment of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. otics as biological drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 76. Drugdex System. Saccharomyces boulardii

2000; 45:1462-4. 2008; 46(suppl 2):S128-32. monograph. Greenwood Village, CO:

45. Marteau P, Lemann M, Seksik P et al. Inef- 60. Kailasapathy K. Microencapsulation Thomson Micromedex (accessed 2009

fectiveness of Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 of probiotic bacteria: technology and Mar 23).

458 Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Mar 15, 2010

You might also like

- فورماDocument11 pagesفورما22368717No ratings yet

- Non Dairy Probiotic Bev - Mini ReviewDocument9 pagesNon Dairy Probiotic Bev - Mini Reviewacharn_vNo ratings yet

- Makalah 2Document8 pagesMakalah 2ainanNo ratings yet

- Pro Bio TicsDocument17 pagesPro Bio TicsMithun90No ratings yet

- Probiotics Review and Future AspectsDocument5 pagesProbiotics Review and Future AspectsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Gut Health From Prebiotic FibresDocument4 pagesGut Health From Prebiotic Fibrescklcat1437No ratings yet

- Application of Probiotics in Food Products PDFDocument7 pagesApplication of Probiotics in Food Products PDFMay MolinaNo ratings yet

- Probiotics and Prebiotics As Functional Foods: State of Art: Review ArticleDocument12 pagesProbiotics and Prebiotics As Functional Foods: State of Art: Review ArticleHania MalikNo ratings yet

- Probiotics and Prebiotics: Effects On Diarrhea: by Guest On 12 March 2018Document9 pagesProbiotics and Prebiotics: Effects On Diarrhea: by Guest On 12 March 2018ajengNo ratings yet

- A-The Importance of Probiotic Institut Rosell Inc. (Montreal, QCDocument4 pagesA-The Importance of Probiotic Institut Rosell Inc. (Montreal, QCAMIT JAINNo ratings yet

- Probiotics Not So PDFDocument3 pagesProbiotics Not So PDFnwkimuin3328No ratings yet

- 15065-Article Text-270676-1-10-20140307Document5 pages15065-Article Text-270676-1-10-20140307mekyno32No ratings yet

- Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Health SciencesDocument6 pagesAsian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Health SciencesadesidasolaNo ratings yet

- EXAMEN - 3EPPLI 30i+RFMHS 6 PDFDocument13 pagesEXAMEN - 3EPPLI 30i+RFMHS 6 PDFS Lucy PraGaNo ratings yet

- Probiotics Nutritional Therapeutic Tool 2329 8901 1000194Document8 pagesProbiotics Nutritional Therapeutic Tool 2329 8901 1000194Javier MartinNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Probiotic Application in Animal Health and Nutrition A ReviewDocument16 pagesRecent Advances in Probiotic Application in Animal Health and Nutrition A Reviewmonica lizzeth VanegasNo ratings yet

- ProbioticDocument36 pagesProbioticstranger13790No ratings yet

- Vip Del Bro Ferment UmDocument0 pagesVip Del Bro Ferment Umabdelaziz_ismail685662No ratings yet

- (Immunology and Microbiology) Edited by Everlon Cid Rigobelo-Probiotics-IntechOpen (2012) PDFDocument635 pages(Immunology and Microbiology) Edited by Everlon Cid Rigobelo-Probiotics-IntechOpen (2012) PDFJonatasPereiraSilvaNo ratings yet

- Prebiotics, Probiotics and SynbioticsDocument42 pagesPrebiotics, Probiotics and SynbioticsDrKrishna DasNo ratings yet

- Pre 2Document6 pagesPre 2ruNo ratings yet

- Health Bene Ts of Probiotics: A Review: Maria Kechagia, Dimitrios Basoulis, (... ), and Eleni Maria FakiriDocument8 pagesHealth Bene Ts of Probiotics: A Review: Maria Kechagia, Dimitrios Basoulis, (... ), and Eleni Maria FakiriDuminda MadushankaNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Experimental Allergy: The Role of Probiotics in The Management of Allergic DiseaseDocument9 pagesClinical and Experimental Allergy: The Role of Probiotics in The Management of Allergic DiseaseKim NhungNo ratings yet

- Overview of Differences Between MicrobiaDocument10 pagesOverview of Differences Between MicrobiaAlanGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Probiotics: An Update To Past ResearchesDocument17 pagesProbiotics: An Update To Past ResearchesBenjamin Light LttNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Ealth Beneftts of Ro Iotics RevieDocument9 pagesReview Article: Ealth Beneftts of Ro Iotics RevieMñz LipeNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Gene TherapyDocument3 pagesThe Benefits of Gene TherapyLevi AckermanNo ratings yet

- Role of Probiotics in Human Health PDFDocument8 pagesRole of Probiotics in Human Health PDFHenry MonologueNo ratings yet

- Probiotics: Presented by Nida E Zehra MSC Biotechnology Sem-IiDocument29 pagesProbiotics: Presented by Nida E Zehra MSC Biotechnology Sem-IiAbbas AliNo ratings yet

- Role of Lactobacillus Reuteri in Human Health and Diseases: Qinghui Mu, Vincent J. Tavella and Xin M. LuoDocument17 pagesRole of Lactobacillus Reuteri in Human Health and Diseases: Qinghui Mu, Vincent J. Tavella and Xin M. LuoHuy Tân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Fish & Shell Fish Immunology: S.K. NayakDocument13 pagesFish & Shell Fish Immunology: S.K. NayakYasir MahmoodNo ratings yet

- 2011 Probiotics Prebiotics and Synbiotics Impact On The Gut Immune System and AllergicDocument11 pages2011 Probiotics Prebiotics and Synbiotics Impact On The Gut Immune System and AllergicAleivi PérezNo ratings yet

- Probiotics Article 2019 PDFDocument10 pagesProbiotics Article 2019 PDFLuiis LimaNo ratings yet

- Application of Microencapsulated Synbiotics in Fruit-Based BeveragesDocument10 pagesApplication of Microencapsulated Synbiotics in Fruit-Based BeveragesBruna ParenteNo ratings yet

- Probiotics and Health: A Review of The Evidence: E. WeichselbaumDocument35 pagesProbiotics and Health: A Review of The Evidence: E. WeichselbaumJavierjongNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: A Gastroenterologist's Guide To ProbioticsDocument18 pagesNIH Public Access: A Gastroenterologist's Guide To ProbioticsFernanda ToledoNo ratings yet

- Probio PCCDocument8 pagesProbio PCCCherry San DiegoNo ratings yet

- 19 Probiotics PrebioticsDocument22 pages19 Probiotics PrebioticsGâtlan Lucian100% (1)

- Clinical Uses of Probiotics: S R M - ADocument5 pagesClinical Uses of Probiotics: S R M - AWahyu RedfieldNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document11 pagesChapter 6Maca Vera RiveroNo ratings yet

- Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics-A ReviewDocument11 pagesProbiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics-A ReviewAnanyaNo ratings yet

- Probiotics: Jonathan D. CrewsDocument11 pagesProbiotics: Jonathan D. CrewsIulia CeveiNo ratings yet

- Probiotics - by Shyam Sunder JayalwalDocument44 pagesProbiotics - by Shyam Sunder JayalwaljayalwalshyamNo ratings yet

- Review 2 ProbioticsDocument4 pagesReview 2 ProbioticsJose Oscar Mantilla RivasNo ratings yet

- Role of ProbioticsDocument2 pagesRole of ProbioticsAJPEDO LIFENo ratings yet

- Guru Nanak Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and TechnologyDocument11 pagesGuru Nanak Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and TechnologySomali SenguptaNo ratings yet

- J. Nutr.-2007-De Vrese-803S-11SDocument9 pagesJ. Nutr.-2007-De Vrese-803S-11SArsy Mira PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Colonisation, Microbiota and Future Probiotics?: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesIntestinal Colonisation, Microbiota and Future Probiotics?: Original ArticleSherif Abou BakrNo ratings yet

- Prebiotics Probiotics Synbiotics Functional Foods PDFDocument6 pagesPrebiotics Probiotics Synbiotics Functional Foods PDFAttila TamasNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Ealth Bene Ts of Ro Iotics RevieDocument7 pagesReview Article: Ealth Bene Ts of Ro Iotics RevieGuneyden GuneydenNo ratings yet

- Acfrogbdptmf56s1siyxu2og1 J8mpghw0xmlmenslfrleoetc66rt7stitnmyxvnbbl2rccbikgrlrtllqdlnljwt6y Adokixllnd6 Rj1cjewjiie7ee4ol1muvu0jof N6vysa79et2lzln7Document5 pagesAcfrogbdptmf56s1siyxu2og1 J8mpghw0xmlmenslfrleoetc66rt7stitnmyxvnbbl2rccbikgrlrtllqdlnljwt6y Adokixllnd6 Rj1cjewjiie7ee4ol1muvu0jof N6vysa79et2lzln7Komang Indra Kurnia TriatmajaNo ratings yet

- Universidad Abierta y A Distancia de México: Licenciatura en Nutrición AplicadaDocument6 pagesUniversidad Abierta y A Distancia de México: Licenciatura en Nutrición AplicadadianaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 10 01723Document27 pagesNutrients 10 01723nguyen thu trangNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Ealth Bene Ts of Ro Iotics RevieDocument8 pagesReview Article: Ealth Bene Ts of Ro Iotics RevieNatália LopesNo ratings yet

- Probiotik Di PencernaanDocument16 pagesProbiotik Di PencernaanAtikah MNo ratings yet

- Pro Bio TicsDocument21 pagesPro Bio TicsNazmul Karim FarukiNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Probiotics and Prebiotics: Genus Species Strain DesignationDocument3 pagesA Guide To Probiotics and Prebiotics: Genus Species Strain DesignationAshutosh Kumar TripathyNo ratings yet

- Prebiotik ProbiotikDocument8 pagesPrebiotik ProbiotikEka PutriNo ratings yet

- Consumer's Guide to Probiotics: How Nature's Friendly Bacteria Can Restore Your Body to Super HealthFrom EverandConsumer's Guide to Probiotics: How Nature's Friendly Bacteria Can Restore Your Body to Super HealthNo ratings yet

- Maternal History InterviewDocument4 pagesMaternal History InterviewaringkinkingNo ratings yet

- Recommended Reading MeterialsDocument160 pagesRecommended Reading MeterialsdilNo ratings yet

- Summative Test No. 2 in Physical Education - 6 Quarter - 1Document6 pagesSummative Test No. 2 in Physical Education - 6 Quarter - 1Ma. Carmela Balaoro100% (1)

- Case Write Up - Dengue FeverDocument22 pagesCase Write Up - Dengue FevervijayaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam in Gec 5Document2 pagesFinal Exam in Gec 5Janine PantiNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument3 pagesResearch ProposalShellaNo ratings yet

- 2013 Constitution of ZimbabweDocument141 pages2013 Constitution of ZimbabweKelly GumboNo ratings yet

- CPR Quiz - Kahoot!Document10 pagesCPR Quiz - Kahoot!jayshondedrick7No ratings yet

- Annual Report 2013 2014Document98 pagesAnnual Report 2013 2014rahulNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda PDFDocument3 pagesAyurveda PDFyuvi087No ratings yet

- Introduction To NCDDocument20 pagesIntroduction To NCDBriantono100% (1)

- Irfan Khan: ProfileDocument3 pagesIrfan Khan: ProfileIrfan AfghanNo ratings yet

- Alternative Healing... What Nobody UnderstandsDocument7 pagesAlternative Healing... What Nobody UnderstandsJonas Sunshine Callewaert100% (1)

- Resume 2Document1 pageResume 2api-339327307No ratings yet

- Unit 13 Managing Human Resources in Health and Social CareDocument4 pagesUnit 13 Managing Human Resources in Health and Social Carechandni0810No ratings yet

- Unstable AnginaDocument5 pagesUnstable AnginaAria AlysisNo ratings yet

- FPM Advanced PainDocument11 pagesFPM Advanced PainHisham SalamehNo ratings yet

- DR Fred Poston Dermatologist To The Stars Has A PracticeDocument1 pageDR Fred Poston Dermatologist To The Stars Has A PracticeAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- ESSIAC Tea BrochureDocument2 pagesESSIAC Tea Brochurepatrickng794No ratings yet

- Blood Culture TV RaoDocument61 pagesBlood Culture TV RaoLavina D'costaNo ratings yet

- Achievements of UAE UnionDocument11 pagesAchievements of UAE UnionShahroz Asif100% (5)

- Project Charter Final VersionDocument16 pagesProject Charter Final Versionapi-240946281100% (3)

- Reading Comprehension 2 "Giving Direction"Document7 pagesReading Comprehension 2 "Giving Direction"Ardi KendariNo ratings yet

- Journal-Of-Hypertension 2Document2 pagesJournal-Of-Hypertension 2Basema HashhashNo ratings yet

- BA5019Document30 pagesBA5019pranay patnaikNo ratings yet

- ChoreaDocument17 pagesChoreaNamarig IzzaldinNo ratings yet

- BM32 Participant List enDocument5 pagesBM32 Participant List enAlbert MusabyimanaNo ratings yet

- Extras From WHS Assessment 2 Template 1Document15 pagesExtras From WHS Assessment 2 Template 1Meghla MeghlaNo ratings yet

- Semi-Annual HSE Performance ReportDocument16 pagesSemi-Annual HSE Performance ReportAbdellatef HossamNo ratings yet

- Nursing Exam Questions Practice Test VDocument6 pagesNursing Exam Questions Practice Test VTiffany D'Alessandro Gordon94% (18)