Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unheard Sounds of the Past

Uploaded by

HansOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unheard Sounds of the Past

Uploaded by

HansCopyright:

Available Formats

An Unheard-of Organology

w hen we look to the past to better understand the present, sometimes things go

missing: they go unreported or under-reported; they never existed or never rose into a position to

be noticed. Usually, a combination of a number of factors is at work. When it comes to music, miss-

ing sounds are literally unheard of, and the classification of their techniques and technologies is an

unheard-of organology. Of course, when something is unheard of, it can also entail a form of abuse.

Luckily, one of the natural habitats of abuse is the editorial, so I would like to take this opportunity

to argue for two new organological categories: aural instruments and significant instruments.

AURAL INSTRUMENTS

Conventional musical instruments are modeled upon the utterance, whether the voice is the instru-

ment or the utterance takes the form of an act of performing upon any other instrument. Simply

stated, we have instrument organologies that privilege sending over receiving. But before discussing

aural instruments, shouldn't we rethink instruments of utterance? And where better to start than

with the voice? The voice in Western culture was long dependent upon a soul situated singularly and

centrally along the axis of a symmetrical body. The same position within the body is also occupied

by the pineal gland, which Descartes thought housed the soul, and the mouth itself.

Two technical practices dislocated the voice forever: ( 1 ) phrenology and early neurology and ( 2 )

phonography. On Franz Joseph Gall's map of the scalp, speech was located off center near the left

frontal lobe, where, in 1839, the French physician Jean Baptiste Bouillaud found it upon the corti-

cal surface of a patient who had, in a botched suicide, shot off part of his skull. Bouillaud wrote, "Cu-

rious to know what effect it would have on speech if the brain were compressed, we applied to the

exposed part a large spatula pressing from above downwards and a little from front to back. With

moderate pressure, speech seemed to die on his lips; pressing harder and more sharply, speech not

only failed but a few words were cut off suddenly" [ I ] .

In a new organology, Bouillaud's spatula would stand proudly next to violins, French horns and

the Moog Synthesizer; is it not to the voice what the piano key is to the string? O r is it the first mod-

ern sampler, albeit in reverse, because the sound is muted? Likewise, when the British neurologist

Wilder Penfield placed, as though it were a phonographic needle settling upon an LP record, a wire

electrode down upon the cortical grooves of a patient, the patient swore he heard a gramophone

playing in the room. "You did have one did you not?" he asked Penfield afterwards [2]. Instead of

bringing flesh upon wire while playing an electric guitar, electric wire is brought down upon flesh

to create an instrument that plays hearing from the biorecording technology called memory. Please

don't try this at home.

Conventional uttered instruments can be in the spirit of Romanticism, where the voice and human

expression has presumptuous, transfigurative power, or in that " 0 " at the head of each line of Expres-

sionist poetry intent upon rhyming with "cosmos." The same can be found underlying the performed

intervals structuring the music of the spheres and in almost all the synaesthetic systems arising within

spiritism, French Symbolism and the Russian avant-garde, in which the two sonic elements attendant

upon humans thatjust so happen to be tied up in the heavens are the periodic waveforms of musical

tones and those of spoken vowels. There would be no problem with this if it were simply humans

making designs upon the heavens or talking to each other, but there are a number of other species

who, as history has proven, suffer terribly when humans are too involved in what it is to be human.

The human ear, however, hears the human voice among all the sounds in the world.

Although the phonograph was known early on as the Speaking Machine, it was also a listening

machine. It not only set the voice askew from the body's symmetrical soul, it exiled the voice from

the body entirely, sending it out to where all things are heard. Preceded scriptually by the alphabeti-

cal recording of speech and the notational recording of music, it was the first general mode of sound

recording to record all sound. Coupled with this ability was a new paradigmatic notion of sound

wherein ideas about one sound and all sound proliferated.

Over three decades later, Luigi Russolo became the first person to systematically incorporate this

phonographic aesthetic within music. Later on, we could clearly hear the phonograph speaking

when John Cage called for sounds to be heard in themselves and proclaimed that all sounds can be

LEONARD0 MUSIC JOURNAL, Vol. 5, pp. 1-3, 1995 1

music; one need only listen. Both Russolo and Cage partook of an important musical strateg?. of the

avant-garde, \\.hereby music, previously consisting of sounds proscribed by the utterances of conven-

tional musical performance, went outside this sphere to incorporate all audible or potentially au-

dible sounds.

Ho~vever,it is important to keep in mind that, contrary to holv the widespread uncritical reception

of Cage's ideas would ha\-e it, the outcome of a desire (where\-er one might find it) to hear all the

sounds of the ~vorldas music not only reiterates the totalizing strains within regimes of utterance, but

also runs counter to his professed anti-anthropomorphism. In the name of the dissolution of the

ego, Cage heard the ~vorldthrough a patently human category achieving through centripetal means

~vllatthe Romantic voice achieved centrifugally. Cage pushed listening quite aggressi\-ely to the ex-

tent that he said that there lvas no such thing as silence; its impossibility ~vascertified by the anechoic

chamber in n.hic11 h e heard his blood circulating and nervous system in operation. Moreo\-er.

microphony might make the entire inaudible world, including ~nolecularvibrations, subject to listen-

ing and thus to music: "That Tve ha\-e no ears to hear the music the spores shot off from basidia make

obliges us to busy ourselves microphonically" [3]. This denial of the finitude of human audition be-

longs to the realm of denials that has historically fueled American enthusiasms and assuaged culpa-

bility, and it demonstrates a desire for an aphenomenal pervasi\-eness of sound that exceeds that of

light: there is no night for the Cagean ear.

Nevertheless, Cage was an important builder and user of t~voof the more notable aural instru-

ments: the piano and the anechoic chamber itself. The piano that "played" Cage's 4'33"is simply the

inverse of the piece performed in the anechoic chamber: muting the surrounding sounds, the

anechoic chamber made the sounds of the body audible, whereas muting the piano displaced atten-

tion to the surrounding sounds. There are rare precursors to Cage's muting: Mayakovsky said after a

\-isit to New York that one should not "extoll noise but . . . put up sound absorbers, we poets must

talk in the carsn[3] and the Dadaist Tristan Tzara suggested that "everything which might make a

sharp sound will be covered with a thin layer of rubber" [j].

The de-amplification of the anechoic chamber, the 4'33" piano, Bouillaud's spatula and Tzara's

rubber are simply the inverse in music, speech and sound of the Cagean microphone that amplifies

absolutely everything. The Cagean microphone has many more precursors, including a conjecture

~vithinthe 1933 Italian Futurist radio manifesto L a Rndia, by F.T. hlarinetti and Pino hlasnata: "The

reception, amplification and transfiguration of vibrations emitted by matter. Just as today we listen

to the song of the forest and the sea so tomorrow shall we he seduced by the vibrations of a diamond

or a flower" [GI. And in the late nineteenth century there was Thomas Edison's "molecular music,"

accidentally disco\-ered as a result of the inadvertent production of sound by means of the carbon

button amplifying the stressed molfements of the telephone handle. An assistant amplified his

memory of this carbon button: "The passage of a delicate camel's hair brush was magnified to the

roar of a mightywind. The footfalls of a tiny gnat sound like the tramp of Rome's cohorts. The tick-

ing of a watch could be heard o\-er a hundred miles" [7].

In Takehisa Kosugi's ,blicro I, from the mid-1960s, a large sheet of paper is cr~impledaround a live

microphone and then left alone to let loose its sounds as it expands: this pun on sheet music implies

that scores, having sufficient materiality and potential for movement, need no instrumental perform-

ers to make music. The insects and other phenomena in David Dunn's recent Chaos @ The Emergrnt

Jlind of the Pond (recorded by means of hydrophones in North American fresh-~vaterponds) ~vould

make us agree with David Cronenberg's Brundle-Fly that the emergent mind has contributing to it a

full-scale insect philosophy. Dunn's critique of Cage argues that Cage decontextualized a n d

musicalized sounds, whereas, "My direct experience of nature convinces me that the \\.orlds I hear

are saturated with an intelligence emergent from the \-ery f~illnessof interconnection which sustains

them. Every living being is a sacred event reaching out from its unique coherence to construct a re-

ality. lye need not anthropomorphize the life around us. Instead we may celebrate those mysterious

occasions which have given rise to each form of mind" [8].

Speaking of mind, Yoko Ono's mind music often bridges the categories of both conceptual and

aural instruments. Her wordscore EIPE PIECE 111, St~ozuPircr (autumn 1963) reads, in part: "Take a

tape of the sound of the snow falling. This should be done in the e\-ening. Do not listen to the tape.

Cut it and use it as strings to tie gifts with." It echoes Hakuin: "How I would ha\-e them hear/In the

\\.oods of Shinoda/At an old temple/\l\'hen the night is deepening/The sound of the snolr-fall!" [9]

Similarly, a 1962 word score by Milan Knizak calls for a radio broadcast of a snowstorm.

Christian hlarclay's more recent The Bratles (1989) is a pillow crocheted from audiotape on ~vllich

all the Beatles' music has been recorded: a true objet r'nore. The potential state of silence in hlarclay's

object is not simply an occasion for contemplative tranquility, because at any instant it can become

audible and boisterous. In this case, the means of amplification belie the existence of psychotechnics

of the type discovered by Penfield's patient. Thus, an object could ostensibly be silent and deafen-

ing at the same time, a koan-like state ironically excluded from Cagean aesthetics.

Historically, the line dividing sound from musical sound was drawn at the threshold of signification

[I()]. The arts somehow overlooked the fact that the worlds of sound are much larger than musical

sound-and this includes twentieth-centu~composition's incorporation. from Russolo on\vards, of

"extra-musical sound" as a means of rein~igoratingmusic. To truly incorporate sound, of course,

would dissolve these bounds of music as they have been historically argued-along with their atten-

dant genre principles-and substantiate areas unambiguously outside existing conceptions of music.

This already occurs within all daily experience of environments and media and across the li~ninal

thresholds of apperception itself. Yet, to understand these phenomena, to bring them effectively

into fields of artistic practice, would require material notions based in poetics and semiosis-not

"musical semiotics." but something emanating from a more comprehensive technique of aurality

that has yet to be developed. How might this affect instruments? M'e can consider how it might im-

pinge upon something already familiar: the sampler. il'here and what exactly is the instrument in

this case? The sound of a normal musical instrument is located and limited by the physical materi-

als, mechanics and acoustics of the instrument itself. However, the sound of a sampler lies in a me-

diated elsewhere or an)where. M'hether the sampled sound is of extinct amphibians o r a quiz s h ~ \ ~

host, the location of the sound-and thus, of the instrument-exists in at least two places at once,

o r modulates between o r arnong two o r more locations. The instrrlment could easily be conceived

as the class of sounds the sampler organizes and the way it organizes them; in this respect, the sam-

pler is not a new instrument, but is the possibi1it:- for an infinity of new instruments. But the design

of samplers is too imbued with music: ho\v could the crude segmentation of a piano keyboard give

way to a significant design? And there is training: the discipline required to master a significant in-

strument may be of the same order as that of a virtuoso sitar or a three-chord guitar in a punk band.

Please try this at home.

DOrGLls IiIHX

Lronardo bIusic Journdl I~zte7nntional( ;o-hdllo~

References

W I ! ~ , '.\, >it. 4 vrrsjoii of this edlto~-ialwas

puhlishetl in Japanese in I n t ~ r ( ; o t s t ? r u n ~ r9i ~(Summer

t ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 1IIII4)

1. F r ~ n c i ,Schiller. Pnul Bror.a (Brrlele\. (:.\: (.nil. of (:alifi)rnia Press. 1979) p. 173

3. f o h n (:age, .A ImrFrots .Ilondn, ( I l i d d l e t o r ~ n(

. :T

Clrslelnn Yni\. Press. 1967) p, 31.

Tire 1 4 oj .\lay~ikoi~\kr.Bolesla~vTnhorski. tranq. (NelvYorli: Orion Press, 19iO) p. 380.

4. IZiLtor Cll~rosr~lski,

5 . Tristdn "/dl-a, "Seeds ' ~ n t lBlan" (19:3.5). .i{~p,p,osimate.Alan ariil Oiher \liilingr, Mar\ Ann C a ~ s trans.

, (Detroit: \ l ' d ~ n eState

Cnll. PI-rs,, 1979) p. 215.

6. F.T. 31'11-inett1m r i Pino Mdznatd. "1.a Rarii,~"(109Y) 111 F.T. 'rlariilrtti, Tvorrn r I i ~ u e x r i o n eI'iit~i~-zsta

ii'erona: -41-noldo

\Iondador1 Editore, 1968) pp. 176-180; trarlslatrd b\ Stephen Sartarrlli in I)ougla> lia1111and Gregor-\ IZl~itelread,rds . Iliru-

Irnaynaiion: Sozlrzd. Rriiiiii nrzd iize Ailnnt-Gnide (Cambridge. I t : \[IT Press. 1992) p p 26.3-268.

7. Frdncis,Jehl..Ilunlii Park Reninis(rntur, \ h l 1 (Ilearhorn. I l l : Edlson Institute, 19:17) p. 140

8. Program notes for the Tokyo Sound(:ultnre performance, S o ~ e n r i ) e1093

~

9. (:ired in 1)alirts T. Suruhi. l.iu!rig b~ Zuti (Toh\o. Sanseido, 1949) p. 183.

10. For an introduirion to this general line of tholcght. see 1)ouglas b h n . "'Track Orgdnolop-," Ortobr755 [ 1090).Reprinted in

Simon Pennv, rii.. C'ntirnl Inuur In Lluiiionir .lled!n ( 4 I h a n ~SI3-k'

: Press. 1!1!11,)

Editorial 3

You might also like

- (Studies in Literature and Science) Michel Serres, Genevieve James, James Nielson-Genesis - University of Michigan Press (1995)Document154 pages(Studies in Literature and Science) Michel Serres, Genevieve James, James Nielson-Genesis - University of Michigan Press (1995)OneirmosNo ratings yet

- Kruth Patricia + Stobart Henry (Eds.) - Sound (Darwin College Lectures, 11) (1968, 2000)Document242 pagesKruth Patricia + Stobart Henry (Eds.) - Sound (Darwin College Lectures, 11) (1968, 2000)mersenne2No ratings yet

- Kontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Four Channels: Temporary Analysis NotesDocument16 pagesKontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Four Channels: Temporary Analysis NotesAkaratcht DangNo ratings yet

- Improvisation Entanglement Awareness PhysicalityDocument6 pagesImprovisation Entanglement Awareness PhysicalitytheredthingNo ratings yet

- CUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonDocument26 pagesCUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonYotam KadoshNo ratings yet

- How To Transpose Music To A New KeyDocument4 pagesHow To Transpose Music To A New KeyIsrael Mandujano Solares100% (1)

- Planarch Codex: The Path of Ghosts: An Ancestral Cult Recently Popular Among Thieves & AssassinsDocument2 pagesPlanarch Codex: The Path of Ghosts: An Ancestral Cult Recently Popular Among Thieves & AssassinshexordreadNo ratings yet

- Poem MakingDocument171 pagesPoem MakingJennifer Thompson100% (2)

- 4 The Meditation Object of Jhana 0Document65 pages4 The Meditation Object of Jhana 0CNo ratings yet

- The Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFDocument11 pagesThe Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFLeonardo Luigi PerottoNo ratings yet

- I Have Never Seen A SoundDocument6 pagesI Have Never Seen A SoundAna Cecilia MedinaNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Nature of HarmonyDocument11 pagesNotes On The Nature of HarmonyxNo ratings yet

- tmp6849 TMPDocument31 pagestmp6849 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Instruments To Perform Color (In 20th Century Music)Document10 pagesInstruments To Perform Color (In 20th Century Music)Aviva Vogel Cohen GabrielNo ratings yet

- Chime Instrument: The Chimes Went Through A Number of DesignDocument6 pagesChime Instrument: The Chimes Went Through A Number of Designapi-283419849No ratings yet

- 19th Century Music - Emerging Aesthetics.Document3 pages19th Century Music - Emerging Aesthetics.pdcraneNo ratings yet

- Psychoacoustics: Art Medium SoundDocument3 pagesPsychoacoustics: Art Medium SoundTheodora CristinaNo ratings yet

- Music's OriginsDocument9 pagesMusic's OriginsEric MorenoNo ratings yet

- 01-A Provisional History of Spectral MusicDocument17 pages01-A Provisional History of Spectral MusicVictor-Jan GoemansNo ratings yet

- Music A Tool - FullDocument6 pagesMusic A Tool - FullTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Improvisation As Dialectic in Vinko Globokar's CorrespondencesDocument36 pagesImprovisation As Dialectic in Vinko Globokar's CorrespondencesMarko ŠetincNo ratings yet

- Music and The Emergence of Experimental Science in Early Modern EuropeDocument17 pagesMusic and The Emergence of Experimental Science in Early Modern EuropeEarth StinkNo ratings yet

- Hans KellerDocument9 pagesHans KellerPaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- CYMATICS Visible SoundDocument3 pagesCYMATICS Visible SoundkurumeuNo ratings yet

- Acousmatics: Chaeff R Calle Dtsclo EdDocument3 pagesAcousmatics: Chaeff R Calle Dtsclo EdPedro Porsu CasaNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument11 pagesResearch Paperapi-660335387No ratings yet

- What Is Musicology 2000Document13 pagesWhat Is Musicology 2000Raman100% (1)

- MeaningS of SoundDocument9 pagesMeaningS of SoundRobert ReigleNo ratings yet

- In-Between Painting and MusicDocument24 pagesIn-Between Painting and MusicSinan Samanlı100% (1)

- Music and ArchitectureDocument18 pagesMusic and ArchitectureJavier Pérez100% (1)

- A Brief History of Violin AcousticsDocument9 pagesA Brief History of Violin AcousticsmahamamaNo ratings yet

- Varese's Vision of Electronic MusicDocument2 pagesVarese's Vision of Electronic MusicSanjana SalwiNo ratings yet

- Presentation 2 The Devil'S IntervalDocument5 pagesPresentation 2 The Devil'S IntervalallysterNo ratings yet

- In Other Words How Stockhausen Stopped WDocument16 pagesIn Other Words How Stockhausen Stopped WFelipeNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Acoustic EcologyDocument4 pagesAn Introduction To Acoustic EcologyGilles Malatray100% (1)

- Music Helps You HealDocument6 pagesMusic Helps You HealJeremy Cabillo100% (1)

- 20th Century MusicDocument5 pages20th Century MusicDavidNo ratings yet

- Barlow SynthrumentationDocument18 pagesBarlow SynthrumentationIgor SantosNo ratings yet

- SLAWSON - The Color of SoundDocument11 pagesSLAWSON - The Color of SoundEmmaNo ratings yet

- Kenneth GaburoDocument2 pagesKenneth GaburoAlexander KlassenNo ratings yet

- Space Resonating Through Sound - Iazzetta y Campesato PDFDocument6 pagesSpace Resonating Through Sound - Iazzetta y Campesato PDFlucianoo_kNo ratings yet

- JOHN YOUNG Reflexions On Sound Image Design PDFDocument10 pagesJOHN YOUNG Reflexions On Sound Image Design PDFCarlos López Charles100% (1)

- Straebel-Sonification MetaphorDocument11 pagesStraebel-Sonification MetaphorgennarielloNo ratings yet

- Future of MusicDocument4 pagesFuture of MusicFrancisco EmeNo ratings yet

- John Cage - Experimental Music DoctrineDocument5 pagesJohn Cage - Experimental Music Doctrineworm123_123No ratings yet

- Scelsi and MessiaenDocument5 pagesScelsi and MessiaenmozartsecondNo ratings yet

- How Music Affects The Brain-41Document5 pagesHow Music Affects The Brain-41api-302958260No ratings yet

- Gesture in Contemporary Music - Edson ZanpronhaDocument19 pagesGesture in Contemporary Music - Edson ZanpronhamykhosNo ratings yet

- What Is SoundDocument16 pagesWhat Is SoundKeys2000No ratings yet

- (Ebook - TXT) Wicca, Magick, Occult - Pythagoras and Circle of FifthsDocument2 pages(Ebook - TXT) Wicca, Magick, Occult - Pythagoras and Circle of FifthsSebekAbRaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Microtonal MusicDocument28 pagesContemporary Microtonal MusicAnonymous IvXgIt8100% (1)

- Comparative Study of Music and Architecture From TDocument18 pagesComparative Study of Music and Architecture From TsubulataNo ratings yet

- Newm Icbox: Sitting in A Room With Alvin LucierDocument10 pagesNewm Icbox: Sitting in A Room With Alvin LucierEduardo MoguillanskyNo ratings yet

- Reynolds VareseDocument61 pagesReynolds VaresePatrick ReedNo ratings yet

- Wishart, Trevor - Sonic Composition in TONGUES of FIRE PDFDocument9 pagesWishart, Trevor - Sonic Composition in TONGUES of FIRE PDFvalsNo ratings yet

- Composing Intonations After FeldmanDocument12 pagesComposing Intonations After Feldman000masa000No ratings yet

- Rwannamaker North American Spectralism PDFDocument21 pagesRwannamaker North American Spectralism PDFImri TalgamNo ratings yet

- Barker 2010 Musical Aesthetics in Ptolemy's Harmonics. ArtDocument19 pagesBarker 2010 Musical Aesthetics in Ptolemy's Harmonics. ArtSantiago Javier BUZZINo ratings yet

- Improvisation As SurrealismDocument12 pagesImprovisation As SurrealismAlejandro Salvatore BenitoNo ratings yet

- Tracking Production Strategies: Identifying Compositional Methods in Electroacoustic MusicDocument15 pagesTracking Production Strategies: Identifying Compositional Methods in Electroacoustic MusicDaríoNowakNo ratings yet

- 026 031 Wire March Joan La BarbaraDocument6 pages026 031 Wire March Joan La BarbararaummusikNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningFrom EverandPostcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningJohannes Salim Ismaiel-WendtNo ratings yet

- Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaFrom EverandBreathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaNo ratings yet

- A Horological and Mathematical Defense of Philosophical PitchFrom EverandA Horological and Mathematical Defense of Philosophical PitchNo ratings yet

- Serres - Feux Et Signaux de Brume - Virginia Woolf's LighthouseDocument23 pagesSerres - Feux Et Signaux de Brume - Virginia Woolf's LighthouseHansNo ratings yet

- F23-Grant WDocument1 pageF23-Grant WHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - Science and The Humanities - The Case of TurnerDocument17 pagesSerres - Science and The Humanities - The Case of TurnerHansNo ratings yet

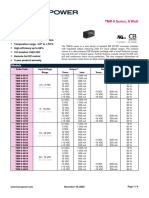

- tmr6 DatasheetDocument4 pagestmr6 DatasheetHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - ('What Are The Questions That Fascinate You' - 'What Do You Want To Know') - ResponseDocument5 pagesSerres - ('What Are The Questions That Fascinate You' - 'What Do You Want To Know') - ResponseHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - Ego Credo PDFDocument12 pagesSerres - Ego Credo PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - India (The Black and The Archipelago) On FireDocument13 pagesSerres - India (The Black and The Archipelago) On FireHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - Origin of Geometry, IV PDFDocument8 pagesSerres - Origin of Geometry, IV PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - Literature and The Exact SciencesDocument33 pagesSerres - Literature and The Exact SciencesHansNo ratings yet

- Bryce HellDocument4 pagesBryce Hellsy734No ratings yet

- Serres and Hallward - The Science of Relations - An InterviewDocument13 pagesSerres and Hallward - The Science of Relations - An InterviewHansNo ratings yet

- Serres - Anaximander - A Founding Name in HistoryDocument9 pagesSerres - Anaximander - A Founding Name in HistoryHansNo ratings yet

- (Niran Abbas) Mapping Michel Serres (Studies in Li PDFDocument238 pages(Niran Abbas) Mapping Michel Serres (Studies in Li PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Being Singular Plural (Nancy)Document57 pagesBeing Singular Plural (Nancy)kegomaticbot420100% (1)

- Michel Serres & Bruno LaTour - Conversations On Science, Culture, and Time.Document216 pagesMichel Serres & Bruno LaTour - Conversations On Science, Culture, and Time.Emre GökNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Critical Social Sciences ) Paul Paolucci-Marx's Scientific Dialectics (Studies in Critical Social Sciences) - BRILL (2007) PDFDocument342 pages(Studies in Critical Social Sciences ) Paul Paolucci-Marx's Scientific Dialectics (Studies in Critical Social Sciences) - BRILL (2007) PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Merleau-Ponty and the Weight of TraditionDocument36 pagesMerleau-Ponty and the Weight of TraditionHansNo ratings yet

- 2013, The Idea of Communism 2 PDFDocument216 pages2013, The Idea of Communism 2 PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - The Nature and Value of EqualityDocument19 pagesCastoriadis - The Nature and Value of EqualityHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - The Retreat From Autonomy - Post-Modernism As Generalized ConformismDocument10 pagesCastoriadis - The Retreat From Autonomy - Post-Modernism As Generalized ConformismHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - The State of The Subject TodayDocument39 pagesCastoriadis - The State of The Subject TodayDavo Lo SchiavoNo ratings yet

- La Crisis Del Proceso de IdentificaciónDocument14 pagesLa Crisis Del Proceso de Identificaciónmiopia611No ratings yet

- Castoriadis - The Logic of Magmas and The Question of AutonomyDocument33 pagesCastoriadis - The Logic of Magmas and The Question of AutonomyHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - Reflections On Racism PDFDocument12 pagesCastoriadis - Reflections On Racism PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - Institution of Society and ReligionDocument17 pagesCastoriadis - Institution of Society and ReligionHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - The Impossibility of Reforms in The Soviet UnionDocument7 pagesCastoriadis - The Impossibility of Reforms in The Soviet UnionHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - Individual, Society, Rationality, HistoryDocument32 pagesCastoriadis - Individual, Society, Rationality, HistoryHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis - From Marx To Aristotle, From Aristotle To UsDocument72 pagesCastoriadis - From Marx To Aristotle, From Aristotle To UsHansNo ratings yet

- Castoriadis, Howard and Pacom - Autonomy - The Legacy of The Enlightenment - A Dialogue WDocument19 pagesCastoriadis, Howard and Pacom - Autonomy - The Legacy of The Enlightenment - A Dialogue WHansNo ratings yet

- The Art of Teresa Wingar p.3Document40 pagesThe Art of Teresa Wingar p.3Rob RiendeauNo ratings yet

- National Poetry Month Activity KitDocument7 pagesNational Poetry Month Activity KitHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNo ratings yet

- When I Was No Bigger Than A Huge by Jose Garcia VillaDocument4 pagesWhen I Was No Bigger Than A Huge by Jose Garcia Villagandaku2No ratings yet

- Literary Movements: ..:: Syllabus 6 Semester::.Document4 pagesLiterary Movements: ..:: Syllabus 6 Semester::.FARRUKH BASHEERNo ratings yet

- PantaloonsDocument32 pagesPantaloonskrish_090880% (5)

- How To Spot A Fake aXXo or FXG Release Before You Download!Document4 pagesHow To Spot A Fake aXXo or FXG Release Before You Download!jiaminn212100% (3)

- Self Talk: 25 Questions To Ask Yourself Instead of Beating Yourself UpDocument8 pagesSelf Talk: 25 Questions To Ask Yourself Instead of Beating Yourself UpMaissa100% (3)

- GrammerDocument9 pagesGrammerParawgay DanarNo ratings yet

- B. Pharm 4th SemDocument30 pagesB. Pharm 4th SemNeelutpal16No ratings yet

- Stair Details by 0631 - DAGANTADocument1 pageStair Details by 0631 - DAGANTAJay Carlo Daganta100% (1)

- Film Analysis Glas by Bert Haanstra: Hrithik Ameet Surana 1810110081Document3 pagesFilm Analysis Glas by Bert Haanstra: Hrithik Ameet Surana 1810110081hrithikNo ratings yet

- Poetry and History - Bengali Ma?gal-K?bya and Social Change in Pre PDFDocument583 pagesPoetry and History - Bengali Ma?gal-K?bya and Social Change in Pre PDFChitralekha NairNo ratings yet

- Pisces Kissing Style: Slow KisserDocument2 pagesPisces Kissing Style: Slow Kisserfadila batoulNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 07 May 2021Document2 pagesAdobe Scan 07 May 2021Puteri AdlyyenaNo ratings yet

- MonacoDocument7 pagesMonacoAnonymous 6WUNc97No ratings yet

- The Self from Philosophical PerspectivesDocument23 pagesThe Self from Philosophical PerspectivesCludeth Marjorie Fiedalan100% (1)

- Resume 2020 - AlanaDocument2 pagesResume 2020 - Alanaapi-508463391No ratings yet

- Wisdom of Hindu Philosophy Conversations With Swami Chinmayanda Nancy Patchen FreemanDocument50 pagesWisdom of Hindu Philosophy Conversations With Swami Chinmayanda Nancy Patchen FreemansrivatsaNo ratings yet

- Parappa The Rapper 2Document65 pagesParappa The Rapper 2ChristopherPeter325No ratings yet

- Skyfall Representation and Global InfluenceDocument37 pagesSkyfall Representation and Global InfluenceDee WatsonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsRedenRosuenaGabrielNo ratings yet

- Sanjeev KapoorDocument12 pagesSanjeev KapoorPushpendra chandraNo ratings yet

- Children of Bodom - Were Not Gonna Fall BassDocument4 pagesChildren of Bodom - Were Not Gonna Fall BassEnrique Gomez DiazNo ratings yet

- Class 8 - TopicsDocument33 pagesClass 8 - TopicsAmit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Pedestrian BridgesDocument16 pagesPedestrian Bridgesdongheep811No ratings yet

- TG - Music 7 - Q1&2Document45 pagesTG - Music 7 - Q1&2Antazo JemuelNo ratings yet