Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Syncope: How The EEG Helps in Understanding Clinical Findings

Uploaded by

Carlos AcostaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Syncope: How The EEG Helps in Understanding Clinical Findings

Uploaded by

Carlos AcostaCopyright:

Available Formats

Scientific Commentaries Brain 2014: 137; 308–312 | 309

replication more effectively than cells from patients with LHON.

Collectively, these findings indicate that mitochondrial mass in- References

creases in response to LHON mutations and large increases may Barboni P, Carbonelli M, Savini G, Ramos Cdo V, Carta A, Berezovsky A,

be protective in asymptomatic carriers. Presumably, the increased et al. Natural history of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy: longitudinal

amount of mitochondrial compensates for the defect of respiratory analysis of the retinal nerve fiber layer by optical coherence tomography.

chain complex I in the patients. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 623–27.

DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system.

Although this excellent translational research study by Giordano

Annu Rev Neurosci 2008; 31: 91–123.

et al. (2014) strongly supports the notion that mitochondrial bio- Giordano C, Iommarini L, Giordano L, Maresca A, Pisano A,

genesis is protective in LHON, proof of this concept will require Valentino ML, et al. Efficient mitochondrial biogenesis drives incom-

identification of the factor(s) responsible for activating mitochon- plete penetrance in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2014;

drial proliferation and experimental manipulation of the biogenesis 137: 335–53.

Giordano C, Montopoli M, Perli E, Orlandi M, Fantin M, Ross-

factors in cells and animal models. If validated and extended,

Cisneros FN, et al. Oestrogens ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction

these observations will have clinical diagnostic and therapeutic im- in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2011; 134: 220–34.

plications, as noted by the authors. For example, they note that Larsson NG, Andersen O, Holme E, Oldfors A, Wahlstrom J. Leber’s

levels of mitochondrial DNA in white blood cells of LHON muta- hereditary optic neuropathy and complex I deficiency in muscle. Ann

Downloaded from http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/ at Belgorod State University on February 6, 2014

tion carriers may prove to be a biomarker predictive of developing Neurol 1991; 30: 701–8.

blindness. Identification of the pathway responsible for mitochon- Leber TH. Ueber hereditäre und congenital-angelegte Sehnervenleiden.

Graefe’s Archiv Ophthalmol 1871; 17: 249–91.

drial DNA biogenesis will provide a pharmacological target to pre-

Newman NJ. Hereditary optic neuropathies: from the mitochondria to

vent blindness in unaffected mutation carriers. Studies have the optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 517–23.

already demonstrated promising therapeutic effects of activating Viscomi C, Bottani E, Civiletto G, Cerutti R, Moggio M, Fagiolari G, et al.

mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse models of mitochondrial dis- In vivo correction of COX deficiency by activation of the AMPK/PGC-

eases with defects of the respiratory chain (Wenz et al., 2008; 1alpha axis. Cell Metab 2011; 14: 80–90.

von Graefe A. Ein ungewöhnlicher Fall von hereditäre amaurose. Arch

Viscomi et al., 2011). Remarkably, Giordano et al. have shown

Ophthalmol 1858; 4: 266–8.

that asymptomatic LHON mutation carriers may already be taking Wallace DC. A new manifestation of Leber’s disease and a new explan-

advantage of enhancing mitochondrial mass to prevent blindness. ation for the agency responsible for its unusual pattern of inheritance.

Brain 1970; 93: 121–32.

Michio Hirano, MD Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, Hodge JA, Schurr TG, Lezza AMS, et al.

Columbia University Medical Centre Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber’s hereditary optic

neuropathy. Science 1988; 242: 1427–30.

New York, NY USA

Wenz T, Diaz F, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Activation of the PPAR/

E-mail: mh29@cumc.columbia.edu PGC-1 alpha pathway prevents a bioenergetic deficit and effectively

improves a mitochondrial myopathy phenotype. Cell Metab 2008; 8:

doi:10.1093/brain/awu005 249–56.

Syncope: how the EEG helps in understanding

clinical findings

Although it is now widely accepted that the key to accurate et al., 2002, 2006; Wieling et al., 2009; Tannemaat et al.,

diagnosis and risk stratification of syncope is a thoughtful 2013).

and scrupulous history, exactly what is meant by the history In this issue of Brain, van Dijk et al. (2014) provide fascinating

remains unclear, and moving it from experts to front-line work- and informative insights into why some symptoms cluster with

ers has proven difficult. Partly this is because syncope is simply a each other in patients with vasovagal syncope. The authors per-

symptom, like fever, with a plethora of potential causes. Partly formed detailed EEG and videometric analyses of 69 patients with

as well this reflects the multitude of somewhat overlapping positive responses to head-up tilt table testing. The EEG provides

symptoms and signs for the most common form, the ‘faint’ or an objective marker of brain dysfunction during the cerebral

vasovagal syncope. There are several clinical features that are hypoperfusion that accompanies syncope. For nearly 60 years

known to be helpful in the differential diagnosis of loss of con- investigators have described EEG patterns during provoked reflex

sciousnesses, based on quantitative symptom studies. These for syncope (Gastaut and Fischer-Williams, 1957; Ammirati et al.,

example help distinguish epileptic convulsions and pseudosyn- 1998; Sheldon et al., 1998; Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2008).

cope from syncope, but such studies were aimed at clinical de- Two patterns have been described. A ‘slow-flat-slow’ pattern is

cision-making. They reported just the most highly significant characterized by an initial slow phase in which delta waves appear

clinical points and do not help clinicians make sense of the and wave amplitude increases, a sudden flattening of the EEG,

welter of symptoms that clinical experience suggests (Sheldon and a return to normal brain activity through a slow phase.

310 | Brain 2014: 137; 308–312 Scientific Commentaries

A ‘slow’ pattern consists only of an increasing and decreasing observed in syncope associated with profound bradyarrhythmia

slowing. The slow-flat-slow pattern was considered to be a sign or asystole during implantable loop recordings (Petkar et al.,

of more severe cerebral hypoperfusion and has been observed 2012). Therefore, in the absence of control groups, such as pa-

more commonly in cardio-inhibitory syncope compared with the tients with non-syncopal loss of consciousness and with syncope

other subtypes, and associated with the presence of convulsive from other causes, it may be a while before we are confident that

movements during syncope. However, with the exception of these clinical sign patterns are useful in the differential diagnosis of

small studies and the specific evaluation of convulsive-like move- transient loss of consciousness. Moreover, signs that can easily be

ments during syncope, few studies have investigated both EEG observed after intensive review of a video might not be easily

patterns and signs and symptoms during syncope. recalled and described by a bystander after a ‘real life’ syncope

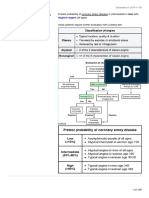

Van Dijk et al. (2014) describe signs and haemodynamic and episode. Second, the video analysis might be biased by both the

EEG changes using videometric data in 69 cases of tilt-induced absence of blinding to EEG results and the camera position, which

vasovagal syncope. Their results confirm that EEG flattening is a did not allow the analysis of peripheral movements.

sign of more severe cerebral hypoperfusion than EEG slowing In conclusion, from a clinical standpoint, this study can help us

alone. Indeed, patients with the slow-flat-slow EEG pattern had in recognizing syncope associated with a deeper hypoperfusion,

a lower minimum blood pressure, longer ECG pauses and duration which might be more symptomatic and require more diagnostic

Downloaded from http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/ at Belgorod State University on February 6, 2014

of loss of consciousness and more often had asystole than those and therapeutic effort. Moreover, the description of symptoms

patients with the slow EEG pattern. In addition, the authors ana- that have rarely been described as associated with syncope, such

lysed several clinical signs occurring during syncope, according to as oral automatisms, might eventually help with the differential

the EEG pattern of the patient and the phase in which they diagnosis of transient loss of consciousnesses with atypical clinical

occurred. As already underlined in previous studies, pallor, sweat- patterns.

ing and having the eyes open during syncope occurred in almost

every patient: the five patients with eyes closed during syncope Monica Solbiati1 and Robert Sheldon2

1

were all in the slow pattern group, suggesting that eye opening Medicina ad Indirizzo Fisiopatologico, Dipartimento di Scienze

might not occur if the brain hypoperfusion is mild. Dilated pupils, Biomediche e Cliniche ‘L. Sacco’, Ospedale ‘L. Sacco’, Università

making sounds, jerks, eye movements and oral automatisms were degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

2

observed in 450% of the population. The authors propose a clas- Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta, University of Calgary,

sification of clinical signs based on their relation to the EEG phase. Calgary, AB, Canada

Type A signs occur during the first slow phase, are present during

the flat phase and stop in the second slow phase. They include Correspondence to: Robert Sheldon, MD, PhD, FRCP(C),

loss of consciousness, eye opening and general stiffening with Professor of Cardiac Sciences,

Libin Cardiocascular Institute of Alberta of the University of Calgary,

possible arm raising. Type B signs occur only during EEG slowing

3280 Hospital Drive NW,

and they likely require some cortical involvement. They include

Calgary, AB, Canada, T2N4N1

myoclonic jerks, nonsensical talking, non-verbal sounds, and au- E-mail: sheldon@ucalgary.ca

tomatisms. Patients also reported auras and near-death experi-

ences. Type C signs occur only during EEG flattening and are doi:10.1093/brain/awt363

mainly roving eye movements and stertorous breathing, suggest-

ive of subcortical generation. Finally, type D signs, including jaw

dropping and snoring, are less specific and may occur in either

phase.

References

The van Dijk et al. (2014) paper provides an important contri- Ammirati F, Colivicchi F, Di Battista G, Garelli FF, Santini M.

Electroencephalographic correlates of vasovagal syncope induced by

bution to our understanding of syncope symptoms. It offers a

head-up tilt testing. Stroke 1998; 29: 2347–51.

unique opportunity to analyse reflex syncope symptoms and Gastaut H, Fischer-Williams M. Electro-encephalographic study of syn-

signs related to EEG changes, and therefore to clarify the patho- cope: its differentiation from epilepsy. Lancet 1957; 273: 1018–25.

physiology of some of the clinical events related to syncope. It Martinez-Fernandez E, Garcı́a FB, Gonzalez-Marcos JR, Peralta AG,

provides insight into why some symptoms are clustered with each Garcia AG, Deya AM. Clinical and electroencephalographic features

of carotid sinus syncope induced by internal carotid artery angioplasty.

other. Moreover, signs that have never been described as syn-

Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 269–72.

cope-related could now help clinicians to distinguish syncope Petkar S, Hamid T, Iddon P, Clifford A, Rice N, Claire R, et al. Prolonged

from other causes of loss of consciousness. implantable electrocardiographic monitoring indicates a high rate of

Nevertheless, before being able to extend the study’s findings to misdiagnosis of epilepsy–REVISE study. Europace 2012; 14: 1653–60.

everyday clinical practice, we must consider that the study has a Sheldon RS, Koshman ML, Murphy WF. Electroencephalographic

findings during presyncope and syncope induced by tilt table testing.

few weaknesses. First, a very selected population in a highly moni-

Can J Cardiol 1998; 14: 811–16.

tored setting was analysed. The same findings may not be true in Sheldon R, Rose S, Connolly S, Ritchie D, Koshman ML, Frenneaux M.

either spontaneous vasovagal syncope or syncope from other Diagnostic criteria for vasovagal syncope based on a quantitative

causes. For example, the onset of partial seizures has been history. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 344–50.

Scientific Commentaries Brain 2014: 137; 308–312 | 311

Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, Connolly SJ, Koshman MS, Lee MA, et al. van Dijk JG, Thijs RD, van Zwet E, Tannemaat MR, van Niekerk J,

Historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Benditt DG, et al. The semiology of tilt-induced reflex syncope in

Cardiol 2002; 40: 142–8. relation to electroencephalography changes. Brain 2014; 137: 576–85.

Tannemaat MR, van Niekerk J, Reijntjes RH, Thijs RD, Sutton R, van Wieling W, Thijs RD, van Dijk N, Wilde AAM, Benditt DG, van Dijk JG.

Dijk JG. The semiology of tilt-induced psychogenic pseudosyncope. Symptoms and signs of syncope: a review of the link between physi-

Neurology 2013; 81: 752–8. ology and clinical clues. Brain 2009; 132: 2630–42.

A (mini) pill for stroke?

In this issue of Brain, Bushra Wali et al. (2014) describe the effi- infarct volume may be a poor guide to functional improvement,

cacy of progesterone in an animal model of ischaemic stroke and, and in many animal models (Howells et al., 2010) the neurobe-

in so doing, provide data of importance for clinical translation, havioural consequences of focal cerebral ischaemia resolve rapidly,

while at the same time raising the bar for high quality reporting meaning that long-term efficacy is difficult to measure. Using a

Downloaded from http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/ at Belgorod State University on February 6, 2014

of in vivo research (Wali et al., 2014). combination of behavioural endpoints, Wali et al. (2014) demon-

The development of new treatments for stroke is a tricky busi- strate firstly that there is a sustained behavioural deficit 3 weeks

ness (O’Collins et al., 2006), and so finding an established drug after the injury, and secondly that the efficacy of progesterone

that might have therapeutic efficacy is a tantalizing prospect. was retained at these later time points. This response appeared

Abundant preclinical data support a neuroprotective effect of pro- to be independent of the delay to treatment—that is, the benefi-

gesterone in experimental stroke and traumatic brain injury, and a cial effect of treatment initiated 6 h after the induction of focal

phase III trial is under way. Given that the safety profile of pro- ischaemia was retained whether outcome was measured 3 days, 9

gesterone is already known, such reprovisioning would accelerate days or 21 days later. Conversely, the lack of benefit of treatment

drug development. A potential confounding influence is sex- and initiated 24 h after ischaemia was largely consistent across times of

age-related differences in circulating progesterone. Women who outcome measurement, although it is a simplification to say there

experience stroke are usually post-menopausal, and modelling the was no efficacy with late treatment; for locomotion (distance tra-

menopause in animals is generally achieved by ovariectomy. In a velled in the open field) and for measures of gait quality (stride

meta-analysis of the effects of progesterone in animal models of length, paw print area, limb swing speed) the data are consistent

focal cerebral ischaemia, Wong et al. (2013) found that proges- with a biologically important effect, which the experiment was not

terone increased mortality in young female hormonally-intact ani- powered to detect. As the authors point out, if efficacy is sus-

mals, and had no effect on lesion volume in adult ovariectomized tained beyond 6 h this would substantially broaden the pool of

females (Wong et al., 2013). In human studies, patients taking patients potentially eligible for progesterone treatment. This effi-

hormone replacement therapy (either oestrogen alone or oestro- cacy at longer delays to treatment suggests effects on regener-

gen plus progesterone) at the time of their stroke seemed to have ation and repair as well as neuroprotection, consistent with reports

a worse outcome (Bath and Gray, 2005); however, the effect of that progesterone promotes post-ischaemia synaptogenesis (Zhao

progesterone on its own is unknown. et al., 2011), increases circulating endothelial progenitor cells (Li

Wali et al. (2014) avoid the confounding effect of circulating et al., 2012), and promotes neurogenesis (Barha et al., 2011) and

progesterone and effects of ovariectomy by restricting attention to neural regeneration (Li et al., 2012).

aged (12-month-old) male rats. They systematically explore the The most important thing about this study, however, is the

limits to efficacy in ways that will help inform clinical trial effort made by the authors to minimize the risk that their findings

design. For delay to treatment, the authors establish that efficacy are confounded by bias (Kilkenny et al., 2010; Landis et al.,

is retained at 6-h delays but lost at 24-h delays, thus validating the 2012). By randomly allocating animals to the various experimental

use of a 6-h window in clinical trials. For drug dose, they show groups, they ensure that the only systematic differences between

maximum efficacy at the lowest dose tested [16 mg/kg on Day 1 the groups were those designed into the experiment. Of course,

(in two doses 5–6 h apart), 8 mg/kg for the next 6 days], with there will be differences between laboratory animals, but the in-

32 mg/kg (Day 1)/16 mg/kg thereafter marginally less effective, vestigators performed a power calculation to ensure that their

and 64 mg/kg (Day 1)/32 mg/kg thereafter clearly less effective. experiment was large enough to account for these chance differ-

These doses are at the higher end of those identified in the review ences and still see any treatment effects of a size considered im-

of Wong et al. (2013) who found no dose-response relationship. portant. The authors take care to report the number of animals

These dosage regimes are, however, loosely analogous to those recruited to each experimental cohort, and the number surviving

that have been used in some clinical trials in traumatic brain injury, ischaemia surgery and to the time that outcome is measured. This

where the total daily dose has ranged from 2 mg/kg to 12 mg/kg. allows the reader to judge whether improved outcome may be

The study by Wali et al. (2014) is also important in that it because of a healthy survivor effect (O’Collins et al., 2011), and

explores efficacy in aged animals with outcomes measured at ex- is particularly important where a drug has previously been re-

tended times after the stroke has occurred. One difficulty in as- ported to increase mortality. Finally, by blinding the assessment

sessing the efficacy of drugs used to treat stroke is that residual of outcome the authors give us greater confidence that the

You might also like

- A 10-Year Old Girl With Neck Pain: Clinical HistoryDocument4 pagesA 10-Year Old Girl With Neck Pain: Clinical HistorywillygopeNo ratings yet

- J Clinph 2013 03 031Document7 pagesJ Clinph 2013 03 031Andres Rojas JerezNo ratings yet

- Neurophysiological Signatures in AlzheimerDocument26 pagesNeurophysiological Signatures in AlzheimerLeslie Silva TamayoNo ratings yet

- Frisoni-11 Criterios ADDocument4 pagesFrisoni-11 Criterios ADMARIA MONTSERRAT SOMOZA MONCADANo ratings yet

- 31-Year-Old Man With Balint'S Syndrome and Visual Problems: Clinical History and NeuroimagingDocument4 pages31-Year-Old Man With Balint'S Syndrome and Visual Problems: Clinical History and NeuroimagingwillygopeNo ratings yet

- Retinal Abnormatilites As A Diagnostic or Prognostic Marker of SchizophreniaDocument6 pagesRetinal Abnormatilites As A Diagnostic or Prognostic Marker of SchizophreniatratrNo ratings yet

- Science Research Journal 15 NovDocument7 pagesScience Research Journal 15 Novnaresh kotraNo ratings yet

- Cognitive ConsequencesDocument4 pagesCognitive ConsequencesMamadou FayeNo ratings yet

- Proximity To Dementia Onset and Multimodal Neuroimaging ChangesDocument12 pagesProximity To Dementia Onset and Multimodal Neuroimaging ChangesaffanbasmalahNo ratings yet

- Gruen 2007Document2 pagesGruen 2007cristianNo ratings yet

- Adult LeucodystrophyDocument12 pagesAdult LeucodystrophylauraalvisNo ratings yet

- Epilepsia - 2019 - Hanin - Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers of Status EpilepticusDocument13 pagesEpilepsia - 2019 - Hanin - Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers of Status EpilepticusAmira GharbiNo ratings yet

- E RefdDocument13 pagesE RefdGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Brainstem LesionsDocument7 pagesBrainstem LesionsErnesto Ochoa MonroyNo ratings yet

- Heterotopia PV GruposDocument12 pagesHeterotopia PV GruposJuan D. HoyosNo ratings yet

- Yoshiyama 2012Document13 pagesYoshiyama 2012yusufNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1795094Document24 pagesNihms 1795094syedrayyanahmed2003No ratings yet

- Neuroimaging Comparison of Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech and Progressive Supranuclear PalsyDocument9 pagesNeuroimaging Comparison of Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech and Progressive Supranuclear PalsyJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraNo ratings yet

- A Clinician's Approach To Peripheral NeuropathyDocument12 pagesA Clinician's Approach To Peripheral Neuropathytsyrahmani100% (1)

- cVEMP y oVEMP en ESCLEROSIS MULTIPLEDocument8 pagescVEMP y oVEMP en ESCLEROSIS MULTIPLEJaneth GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Neuropharmacology: Tjitske Kleefstra, Annette Schenck, Jamie M. Kramer, Hans Van BokhovenDocument12 pagesNeuropharmacology: Tjitske Kleefstra, Annette Schenck, Jamie M. Kramer, Hans Van Bokhovenastir1234No ratings yet

- 2020 Clinical Association of White MatterDocument9 pages2020 Clinical Association of White MatterMarco MerazNo ratings yet

- Art Acta - Neurol.belgicaDocument6 pagesArt Acta - Neurol.belgicaAna GabrielaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Diagnostic Techniques in The Differential Diagnosis of Epileptic and Nonepileptic SeizuresDocument34 pagesA Review of Diagnostic Techniques in The Differential Diagnosis of Epileptic and Nonepileptic Seizurestayfan1No ratings yet

- Botulinum Toxin A For Upper Limb SpasticityDocument3 pagesBotulinum Toxin A For Upper Limb SpasticityTerrence ChanNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory Cortical Demyelination in Early Multiple SclerosisDocument10 pagesInflammatory Cortical Demyelination in Early Multiple SclerosisWulan AzmiNo ratings yet

- New Insights Into The Pathophysiology of Alzeimer's DiseaseDocument2 pagesNew Insights Into The Pathophysiology of Alzeimer's DiseaseMarília Cavalcante LemosNo ratings yet

- Evidence of CNS Impairment in HIV Infection: Clinical, Neuropsychological, EEG, and MRI/MRS StudyDocument7 pagesEvidence of CNS Impairment in HIV Infection: Clinical, Neuropsychological, EEG, and MRI/MRS StudyLuther ThengNo ratings yet

- Frohman 2006Document11 pagesFrohman 2006Alfredo Enrique Marin AliagaNo ratings yet

- Proof of Progression Over Time Finally Fulminant Brain Muscle An 2009 SeiDocument3 pagesProof of Progression Over Time Finally Fulminant Brain Muscle An 2009 Seibilal hadiNo ratings yet

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome After Lumbar PunctureDocument2 pagesPosterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome After Lumbar PunctureMedtext PublicationsNo ratings yet

- BH 010060 ENGDocument2 pagesBH 010060 ENGCarlosNo ratings yet

- Biomarcadores Neuroinmunes en Esquizofrenia. 2014Document11 pagesBiomarcadores Neuroinmunes en Esquizofrenia. 2014Stephanie LandaNo ratings yet

- Advantage of Modified MRI Protocol For HDocument148 pagesAdvantage of Modified MRI Protocol For HasasakopNo ratings yet

- Wang 2004Document13 pagesWang 2004Ricardo Jose De LeonNo ratings yet

- Cerri Et Al. 2017Document7 pagesCerri Et Al. 2017JD SánchezNo ratings yet

- Vertigo MeniereDocument5 pagesVertigo MeniereHamba AllahNo ratings yet

- Consensus Paper of The WFSBP Task Force On Biological Markers of Dementia The Role of CSF and Blood Analysis in The Early and Differential DiagnosisDocument17 pagesConsensus Paper of The WFSBP Task Force On Biological Markers of Dementia The Role of CSF and Blood Analysis in The Early and Differential DiagnosisDeepthi Chandra Shekar SuraNo ratings yet

- 356 FullDocument15 pages356 FullLeonel Ivan AngelesNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer Mechanisms and Therapeutic StrategiesDocument19 pagesAlzheimer Mechanisms and Therapeutic StrategiesArtemis LiNo ratings yet

- Visual Evoked Potentials in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: MethodsDocument6 pagesVisual Evoked Potentials in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: MethodsYulianti PurnamasariNo ratings yet

- 人工智能在神经病理学中的应用:基于深度学习的tau蛋白病变评估Document23 pages人工智能在神经病理学中的应用:基于深度学习的tau蛋白病变评估meiwanlanjunNo ratings yet

- Fnana 12 00025Document11 pagesFnana 12 00025Mohamed TahaNo ratings yet

- Discoveries 08 110Document19 pagesDiscoveries 08 110Riki AntoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis Bench To Bed - Alexzander A.A. Asea, Fabiana G PDFDocument189 pagesMultiple Sclerosis Bench To Bed - Alexzander A.A. Asea, Fabiana G PDFHîrjoabă IoanNo ratings yet

- Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers of Status Epilepticus - 2020Document40 pagesCerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers of Status Epilepticus - 2020Reny Wane Vieira dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Flanagan Et Al 2014 EEG-fMRI Focal Epilepsy - Local Activation and Regional NetworksDocument11 pagesFlanagan Et Al 2014 EEG-fMRI Focal Epilepsy - Local Activation and Regional NetworksCindy ZuritaNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Pitfalls in Scalp EEG - Current Obstacles and Future Directions - SandorDocument21 pages2023 - Pitfalls in Scalp EEG - Current Obstacles and Future Directions - SandorJose Carlos Licea BlancoNo ratings yet

- Zs Urka 2013Document4 pagesZs Urka 2013trukopNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning: A Young Man With Recurrent Paralysis, Revisable White Matter Lesions and Peripheral Neuropathy Word Count: 945Document13 pagesClinical Reasoning: A Young Man With Recurrent Paralysis, Revisable White Matter Lesions and Peripheral Neuropathy Word Count: 945aileenzhongNo ratings yet

- Nonepileptic Seizures - An Updated ReviewDocument9 pagesNonepileptic Seizures - An Updated ReviewCecilia FRNo ratings yet

- Vestibular Neuritis, or Driving Dizzily Through Donegal: PerspectiveDocument2 pagesVestibular Neuritis, or Driving Dizzily Through Donegal: PerspectiveBono GatouzouNo ratings yet

- EEGfindingsinCOVID 19relatedencephalopathyDocument5 pagesEEGfindingsinCOVID 19relatedencephalopathyLeonardo PunshonNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0969996120304940 MainDocument22 pages1 s2.0 S0969996120304940 MainAmanda MosiniNo ratings yet

- Si OlfatorioDocument15 pagesSi OlfatorioMariana Lizeth Junco MunozNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical NeuroscienceDocument3 pagesJournal of Clinical NeurosciencejicarrerNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0149763421002682 MainDocument21 pages1 s2.0 S0149763421002682 MainAna Catarina De Oliveira Da Silv LaborinhoNo ratings yet

- So 2010Document10 pagesSo 2010Pablo Sebastián SaezNo ratings yet

- Mean Diffusivity and Fractional Anisotropy As Indicators of Disease and Genetic Liability To SchizophreniaDocument18 pagesMean Diffusivity and Fractional Anisotropy As Indicators of Disease and Genetic Liability To SchizophreniaAlexander AnhaiaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Seized: Linguistic Considerations of the Effects of Epilepsy on Cognition in Children with Benign Childhood EpilepsyFrom EverandChildhood Seized: Linguistic Considerations of the Effects of Epilepsy on Cognition in Children with Benign Childhood EpilepsyNo ratings yet

- 2007 Fundamentals of Eeg TechnologyDocument46 pages2007 Fundamentals of Eeg TechnologyJoshua ParikesitNo ratings yet

- Localización EegDocument5 pagesLocalización EegCarlos AcostaNo ratings yet

- Acute EEG Patterns Associated With Transient Ischemic AttackDocument9 pagesAcute EEG Patterns Associated With Transient Ischemic AttackCarlos AcostaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Laplacian Montages: American Journal of Electroneurodiagnostic TechnologyDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Laplacian Montages: American Journal of Electroneurodiagnostic TechnologyCarlos AcostaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Abou Khalil Montages Polarity Localization HandoutDocument86 pagesLecture 1 Abou Khalil Montages Polarity Localization HandoutPablo MartinezNo ratings yet

- The AASM Manual For The Scoring of Sleep and Associated EventsDocument136 pagesThe AASM Manual For The Scoring of Sleep and Associated EventsSerkan KüçüktürkNo ratings yet

- AASM Visual Scoring Infants ChildrenDocument44 pagesAASM Visual Scoring Infants ChildrenCarlos AcostaNo ratings yet

- ClinicalNeurophysiology3e2009 PDFDocument915 pagesClinicalNeurophysiology3e2009 PDFriddhi100% (2)

- SyncopeDocument58 pagesSyncopeNabeel Kouka, MD, DO, MBA, MPH100% (1)

- Apo Prazosin PiDocument9 pagesApo Prazosin PiNadya UtariNo ratings yet

- Shadow Health Anxiety - SubjectiveDocument5 pagesShadow Health Anxiety - SubjectiveKatherine Smith100% (1)

- VT 2Document49 pagesVT 2Micija CucuNo ratings yet

- Lvot o IiDocument179 pagesLvot o Iimona300No ratings yet

- Approach To Seizures in ChildrenDocument12 pagesApproach To Seizures in ChildrenShamen KohNo ratings yet

- Dehydration: By: M. SofyanDocument2 pagesDehydration: By: M. Sofyansofyan novrizalNo ratings yet

- Holly Barlow-Austin LawsuitDocument57 pagesHolly Barlow-Austin LawsuitNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- CPR I Prva PomocDocument169 pagesCPR I Prva PomocBudimirOrbiterNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 PDFDocument5 pagesChapter 6 PDFMay ChanNo ratings yet

- Sword Art Online Progressive - Volume 01 PDFDocument400 pagesSword Art Online Progressive - Volume 01 PDFAditya D NegiNo ratings yet

- Passmedicine Top 100 ConceptsDocument9 pagesPassmedicine Top 100 Conceptsmohamed elyasNo ratings yet

- Patient Evaluation and Wound Assessment: Key Practice PointsDocument6 pagesPatient Evaluation and Wound Assessment: Key Practice PointsFofiuNo ratings yet

- 16 Vascular Diseases of Nervous System-QDocument24 pages16 Vascular Diseases of Nervous System-QAdi PomeranzNo ratings yet

- IMS MCQ Bank 2023 VXDocument28 pagesIMS MCQ Bank 2023 VXAbdulrahman AlharbiNo ratings yet

- MCQ of NeurologyDocument45 pagesMCQ of Neurologyeffe26100% (6)

- Health Teaching Plan (PRINT)Document11 pagesHealth Teaching Plan (PRINT)CG Patron BamboNo ratings yet

- Vertigo and DizzinessDocument14 pagesVertigo and Dizzinessa7mad thunaibatNo ratings yet

- 1, Assessment 3 CHCPRP003 Reflect On and Improve Professional PracticeDocument43 pages1, Assessment 3 CHCPRP003 Reflect On and Improve Professional PracticeRashid Mahmood Arqam100% (1)

- Focus Charting Review PDFDocument9 pagesFocus Charting Review PDFTenIs ForMeNo ratings yet

- Altered Tissue PerfusionDocument10 pagesAltered Tissue PerfusionLaurence ZernaNo ratings yet

- Hi-Yield Notes in Im & PediaDocument20 pagesHi-Yield Notes in Im & PediaJohn Christopher LucesNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVE STUDY ON KENT by GaskinDocument18 pagesCOMPARATIVE STUDY ON KENT by GaskinmdasNo ratings yet

- NBME 1 Block 1 - 4 EditedDocument77 pagesNBME 1 Block 1 - 4 Editedalex karevNo ratings yet

- Dzudie 2020Document7 pagesDzudie 2020Andi Tiara S. AdamNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Medical Emergencies in The Dental Office 7th Edition Stanley F MalamedDocument3 pagesTest Bank For Medical Emergencies in The Dental Office 7th Edition Stanley F MalamedMisti Keane100% (34)

- Bowel Nosodes by PatersonDocument28 pagesBowel Nosodes by PatersonBhaskar Datta75% (4)

- Zanki Step 2 - Cardiovascular SystemDocument129 pagesZanki Step 2 - Cardiovascular SystemChunlei WangNo ratings yet

- Du 26Document2 pagesDu 26BDI92No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument37 pagesUntitledclaudiaNo ratings yet