Professional Documents

Culture Documents

978-1-4899-3458-1 - 11 Logo Caballito

Uploaded by

Daniela Tapia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views2 pagesOriginal Title

978-1-4899-3458-1_11 logo caballito

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views2 pages978-1-4899-3458-1 - 11 Logo Caballito

Uploaded by

Daniela TapiaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Acquired aphasia in

childhood

Childhood speech-language disorders can be divided into develop-

mental disorders and acquired disorders (Ludlow, 1980). Developmental

disorders of speech and language are those which onset prior to the

emergence of language (Le. between birth and one year of age).

Consequently children with developmental language disorders have

never developed language normally. Although it is usually presumed

that primary developmental speech-language disorders are caused by

dysfuflctioning of the central nervous system, in most cases they have

an idiopathic origin (Le. the cause is unknown). Developmental

speech-language disorders can, however, occur secondary to con-

ditions such as peripheral hearing loss, mental retardation, cerebral

palsy, child autism, birth trauma and environmental deprivation.

Acquired speech-language disorders, on the other hand, are

disturbances in speech-language function that result from some form

of cerebral insult after language acquisition has already commenced

(Hecaen, 1976). The cerebral insult, in turn, can result from a variety

of aetiologies, including head trauma, brain tumours, cerebrovascular

accidents, infections, convulsive disorders (intractable epilepsy) and

electroencephalographic abnormalities (Miller et at., 1984). Typically

these children have commenced learning language normally and were

acquiring developmental milestones at an appropriate rate prior to

injury.

Of the two types of childhood language disorder, the acquired

variety most closely resembles the acquired adult communicative

disorders discussed in earlier chapters. Unfortunately, many texts on

the language disorders in the past have paid this important group of

neurologically based speech-language disorders only scant attention.

This chapter will review acquired childhood speech-language dis-

orders in terms of their aetiology and clinical features.

B. E. Murdoch, Acquired Speech and Language Disorders

© B.E. Murdoch 1990

Acquired childhood aphasia 283

11.1 ACQUIRED CHILDHOOD APHASIA

11.1.1 Clinical features of acquired childhood aphasia

Children with acquired language disorders are referred to as having

acquired aphasia. The clinical features of acquired childhood aphasia

are manifestly different in a number of ways to those of adult aphasia.

In particular, there appear to be two major differences between

acquired aphasia in children and aphasia in adu~ts. First, the

recovery process is described as being more rapid and complete in

children (Lenneberg, 1967). Secondly, in the majority of cases,

acquired childhood aphasia is predominantly non-fluent, its major

features being mutism and lack of spontaneity of speech (Alajouanine

and Lhermitte, 1965; Hecaen, 1976; Fletcher and Taylor, 1984).

Further, with some rare exceptions, the acquired aphasia in children

does not appear to fall into clear-cut syndromes evocative of the well-

known aphasia sub-types described in adults (see Chapter 2).

Although there is some variation between reports in the literature,

the symptoms most reported in the classical studies to be character-

istic of acquired childhood aphasia include initial mutism (suppression

of spontaneous speech) followed by: a period of reduced speech

initiative; a non-fluent speech output; simplified syntax (telegraphic

expression); impaired auditory comprehension abilities (particularly in

the early stages post-onset); an impairment in naming; dysarthria; and

disturbances in reading and writing (primarily in the acute stage post-

onset). Most authors suggest that fluent aphasia and receptive dis-

orders of oral speech such as literal and verbal paraphasic errors,

logorrhoea, and perseverations are only rarely found in children with

acquired aphasia. There is, however, evidence to suggest that the age

of the child has a role to play in determining whether or not these

symptoms occur in a particular case. Some authors are of the opinion

that the primarily non-fluent pattern of aphasia is only prevalent in

children who are less than ten years of age at the onset of the aphasia

(Poetzl, 1926; Guttmann, 1942; Alajouanine and Lhermitte, 1965). For

example, Alajouanine and Lhermitte (1965) found that the pre-

dominant features of the acquired aphasia demonstrated by children

at < 10 years of age included decreased auditory comprehension,

severe writing deficit, and no logorrhoea, paraphasias or persever-

ation. These same authors, however, reported that the acquired

aphasia demonstrated by children > 10 years of age is a more fluent

form of aphasia, with paraphasia present, less frequent articulatory

and phonetic disintegration and disturbed written language. Other

authors, however, are of the opinion that the non-fluent type of

You might also like

- Treatment in Epileptic Encephalopathy With ESES and Landau-Kleffner SyndromeDocument6 pagesTreatment in Epileptic Encephalopathy With ESES and Landau-Kleffner SyndromeDaniela TapiaNo ratings yet

- Department of Neuropediatrics U.C.L. 10/1303 St. Luc University Clinic 10, Avenue Hippocrate 1200 Brussels BelgiumDocument2 pagesDepartment of Neuropediatrics U.C.L. 10/1303 St. Luc University Clinic 10, Avenue Hippocrate 1200 Brussels BelgiumDaniela TapiaNo ratings yet

- Acquired Cmldhood Aphasia: Outcome One Year After OnsetDocument2 pagesAcquired Cmldhood Aphasia: Outcome One Year After OnsetDaniela TapiaNo ratings yet

- 978-94-011-3582-5 - 3 Caballito LogoDocument2 pages978-94-011-3582-5 - 3 Caballito LogoDaniela TapiaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Gait Analysis For Assessment of Chronic Low Back Pain From Lumbar Facet JointsDocument8 pagesGait Analysis For Assessment of Chronic Low Back Pain From Lumbar Facet Jointspion tvNo ratings yet

- Colostomy Care: Sital B Sharma MSC Nursing Part I Con, NBMCDocument39 pagesColostomy Care: Sital B Sharma MSC Nursing Part I Con, NBMCShetal Sharma100% (1)

- Torsten Zuberbier, Clive Grattan, Marcus Maurer Urticaria and AngioedemaDocument256 pagesTorsten Zuberbier, Clive Grattan, Marcus Maurer Urticaria and AngioedemasajithaNo ratings yet

- Vocal Function Exercises For Presbylaryngis: A Multidimensional Assessment of Treatment OutcomesDocument10 pagesVocal Function Exercises For Presbylaryngis: A Multidimensional Assessment of Treatment OutcomesJulia GavrashenkoNo ratings yet

- Ma A LoxDocument2 pagesMa A LoxMicah_Ela_Lao_2724No ratings yet

- Reckeweg Base 10 PDFDocument2 pagesReckeweg Base 10 PDFTrikala2016No ratings yet

- Techniques in BandagingDocument2 pagesTechniques in BandagingKate William DawiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Medical Surgical Nursing Patient Centered Collaborative Care 7th Edition IgnataviciusDocument9 pagesTest Bank For Medical Surgical Nursing Patient Centered Collaborative Care 7th Edition IgnataviciusM Syaiful Islam43% (7)

- Minimally Invasive Lumbar Spine SurgeryDocument29 pagesMinimally Invasive Lumbar Spine SurgerySourabh AlawaNo ratings yet

- Module 13 Health CareDocument69 pagesModule 13 Health CareCid PonienteNo ratings yet

- Rilantono, Lily L. 5 Rahasia Penyakit Kardiovaskular (PKV) - Jakarta: Badan Penerbit Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia 2012. p.279-287Document1 pageRilantono, Lily L. 5 Rahasia Penyakit Kardiovaskular (PKV) - Jakarta: Badan Penerbit Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia 2012. p.279-287Tegar DharmaNo ratings yet

- Corporate OverviewDocument45 pagesCorporate OverviewMohit SinghNo ratings yet

- Appliedmicro Micro D& R AgamDocument83 pagesAppliedmicro Micro D& R Agamjanijkson29No ratings yet

- Introduction - CPR PerspectiveDocument62 pagesIntroduction - CPR PerspectiveImtiaz AhmadNo ratings yet

- Guava Leaves As Soap Research PaperDocument5 pagesGuava Leaves As Soap Research Papergz8pjezc100% (1)

- Pandemic MGT Module UGDocument113 pagesPandemic MGT Module UGFantastic AswinNo ratings yet

- Rguhs Thesis Topics in OrthopaedicsDocument6 pagesRguhs Thesis Topics in Orthopaedicsjanetrobinsonjackson100% (1)

- Investigatory Biology Calss 12Document19 pagesInvestigatory Biology Calss 12DEEPAKNo ratings yet

- Thesis Diabetes Mellitus PDFDocument5 pagesThesis Diabetes Mellitus PDFdeborahgastineaucostamesa100% (2)

- Text Book For B.A BSW 1st Sem EnglishDocument32 pagesText Book For B.A BSW 1st Sem EnglishAdam CrownNo ratings yet

- 37 - Shock in ObstetricsDocument22 pages37 - Shock in Obstetricsdr_asaleh90% (10)

- Đề 9. Đề thi thử TN THPT môn Tiếng Anh theo cấu trúc đề minh họa 2021 - Cô Oanh 9 - Có lời giảiDocument14 pagesĐề 9. Đề thi thử TN THPT môn Tiếng Anh theo cấu trúc đề minh họa 2021 - Cô Oanh 9 - Có lời giảiBình Bùi thanhNo ratings yet

- Hematology: Mohamad H Qari, MD, FRCPADocument49 pagesHematology: Mohamad H Qari, MD, FRCPASantoz ArieNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER-12 - Community Health NursingDocument8 pagesCHAPTER-12 - Community Health Nursingjanmishelle208No ratings yet

- DR Shubham Gare Orthopaedics Synopsis PresentationDocument13 pagesDR Shubham Gare Orthopaedics Synopsis PresentationdrshubhamgareNo ratings yet

- Management of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineDocument9 pagesManagement of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineNur IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Classification Pathophysiology Diagnosis and ManagDocument10 pagesClassification Pathophysiology Diagnosis and ManagHeru SetiawanNo ratings yet

- BicitraDocument1 pageBicitraKerra AnasatasiaNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National UniversityDocument44 pagesMinistry of Education and Science of Ukraine V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National UniversityDrTushar GoswamiNo ratings yet

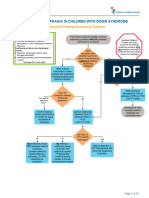

- Aspiration and Dysphagia in Children With Down SyndromeDocument23 pagesAspiration and Dysphagia in Children With Down SyndromeJessa MaeNo ratings yet