Professional Documents

Culture Documents

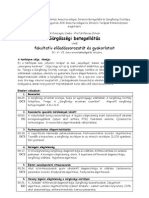

George

Uploaded by

Maria Zsuzsanna Fortes0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views10 pagesOriginal Title

george

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views10 pagesGeorge

Uploaded by

Maria Zsuzsanna FortesCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

Ik is seven o'clock on a late-

ward 12-year-old Romania

Jowibh iamigran¢ ito, at 3

ete ae ay

quietly in the background. %

Sheen Jit macoon. drapes :

I alice Ui ty claborste aa is lay hol elas

Lal fugless chandeliers, the esta Kozinski clerked at the US.

Teovbas te genie aunosphere Con of Appeals al it fo

fan exclave Baglsh “ Giet

fan amblence enhanced by the

ce

ederal

P

Kozinski in

A snowboarding libertarian and bungee-jumping intellectual, Alex Kozinski is one

‘of the most provocative and influential Federal judges in the country today. As he ~

leads his one-man charge to remake American law in a conservative mold, he's als

keeping his eyes on another prize—a seat on the Supreme Court. By Robert S.Boynton

3

youngest person. appointed

tothe Federal bench in this con

ish Tnke man, Kozioska tury Dr

blue windbreaker, a sirped ten-year, itwas an apen sec

tis shirt and jeans, which indi-

fate his unceremonious atstude

roward ifeoffthehench: Aftera —pointment many think will

day of bslinicing the scales of occur if a Republican wins the

justice, the eschews all White House next Ni

by night. The recent Suprem:

discrepancy between himself — qominees, Kozinski doesn't

hesitate to trumpet his julie

da: “E want co change

‘of American jurispri=

Spent most of his life standing dence,” he has declated.

apart fiom the cre jen his considerable

Sipping fom

says—indeed, Kozinski has

sion, energy and imellecusal

DAVIS FACTOR

cociousnes, one might think of

Kozinski as the Newt Gingrich

ofthe judicial branch—a preter

naturally youthful, superspatsi-

otic libertarian, who believes

that the combination of ad-

vanced technology, small gov=

femnment and fice markets will

steer America twvantits loro

manifest destiny, Kozinski

ideas have found fertile soi in

the Newtonian era, his engage

ing prose popping up in a dizey-

ing array of Supreme Court

decisions, la jouemals, newspa-

pers, textbooks and legal brie

‘The conservative judge Richard

Posner als him “one ofthe best

and smartest judgesin the coun-

‘ry and Harvaed constitutional

scholar Laurence Tibe consid-

cershim “one ofthe few genuine

ly interesting minds in the

Federal judiciary.” Clint Bolick,

the litigation director of the con:

servaive Institute fr Justice and

the man who helped torpedo

Lani Guinice’s nomination for

assistant attorney general, says if

he were “advising a peesdenton

the Supreme Court, Alex would

bbeon the top of my is.”

Much of Kozinski’s wide ap-

peal stems from his relentlessly

commonsense approach to lav

He believes in simple princi

ples: Cantraets should be bind

ing; people who take stupid

‘sks shoulda’t win millions of|

dollars in damages; the cones

should follow the language

of the Constitution, Ever

skeptical about governmental

interference, he possesses an

unbridled ‘enthusiasm for

property rights and the free

‘market. “Economie liberty isa

civil Uber.” he writes, “as fian-

damental as voting, travel, reli-

gion or speech.” In one

address, he jokingly envisions

American history through the

Piece by piece,

Kozinski offers up

artifacts from his

life—videotapes

of himself bungee-

jumping, and the

program and some

pictures from his

son's bar mitzvah

eee

lens of present-day litigious

ness: “Asked whether he cut

down his father’s cherry tre,

George Washington would

have taken the Fifth”

‘But Kozinski doesn’t always

‘come across like a Gingrich in

black robes: Because he sees

‘the Constitution as primarily

document that limits govern

‘ment, his postions on criminal

Jaw and defendants’ rights aze

notably liberal. He is no

rmoralist, and believes thar gov.

cemment should have as bile

power in the private sphere as

inthe publicone, He has ruled

for pomographers who “incor-

rectly guess” the age of an un-

erage actress, and has argued

that the First Amendment

protects flag burners,

“Alex is one of the true

conservative libertarians in

public life today.” says Harvard

Law School professor Alan

Dershowitz. “He shakes his fin

ger at fellow conservatives and

tells them to scrutinize govern

ment tall levels noejustwhere

ithelps their wallets”

Another reason for Kozin-

skis influence and popularity

is that he presents his ideas

with clarity and—believe it oF

nor—humor. Refreshingly

fice ofthe mangled legaese fi

vored by most jurists, his best

opinions read like pieturesque

shore stories, complete with

sharply drawn characters and

pithy morals. “Every market

hhas ite dreamers and ite

crooks,” he concludes in one

cease, and “occasionally they are

fone and the same.” A film fi

atic, he once covertly weaved

215 movie titles into an opinion,

about a Nevada cinema owner

In a Yale Law Journal article

fon Yiddish and law titled

“Lawsuit, Shmawsuit,” he

pondered the fact that the

hhame Schmuck is more com-

mon than the name Mensch

“Pethaps this is because there

are more schmucks than men-

sches,” he suggests

‘Kozinsk’s literary produe-

som doesn’e stop at leg opin

fons: While he has ambitions

to write a novel, he is more ex-

cited about his screenplay,

which chronicles the bitter

war being waged on America’s

slopes herween skiers and

snowboarders. An avid snow-

boarder himself, Korinski sides

with the latter, “The chase

scene would be lke something

from On Her Majesty's Secret

Service,” he says."“nd ofcourse,

Td work in a nice Endangered

Species Actangle.”

When he isn’t snowboard-

ing he's been known to bungee-

jump off 13-story cranes, He

reviews video games for the

Will Seeet Journal and books

for the New Republic and the

New York Times, He interviews

potential lw clerks aver poke

and since the ones he hires

‘work like dogs for him, he'll oc-

casionally take them to Las

Vegas to gamble. He is an ac-

‘complished amateur magician

and ofien practices new wicks

in his chambers. He has even

been known to break out in

song during his lectures. tone

symposium, he announced he

had unearthed the song Reagan

‘composed for Justice Antonin

Scali’s nomination, which he

then sang to the tune of

Leonard Bernstein's “Mari

“Scalia, I just picked a judge

named Scalia.

But some coure-watchers be-

lieve that Kozinski wields the

gavel offustice like a magician’s

‘wand, obscuring reactionary

poli~ (continued on page 24)

DAVIS FACTOR

Wise Guy

{continued from page 174) tes with rhetori-

caleloquenceand personal appeal. "Kezinski

gets away with a lo because he isso funny

‘and chatming,” says Nan Aron, president

of the liberal Alliance for Justice. “But he is

also very dangerous, especially with regard

to the rights of immigrants, workers and

the poor. Property rights always trump

Ihumaa rights for him.”

‘The possbiltythat Kozinské mightend up

‘on the Supreme Court adds urgency to liber

al’ criticisms. ‘They note that even fom bis

‘seat on the appeals court, Kozinski takes an

‘extremely broad view of his role as a judge,

approaching each case with an eye toward

changing the law—and society —asa whole.

‘Some colleagues gromble about what they

describe as bis arrogance and grandstanding,

‘one going so faras to call him “a smare-aleck.

pain in the ass" The more serious criticisms,

however, suggest that Kozinshi, beyond hav

ing litle sympathy for the welfare state, is de-

liberately undermining it. Fellow Ninth

Circuit judge Stephen Reinhart, a passion-

ate liberal and close friend of Kozinsk

also one of his harshest crt

think of his views? Not much

ly ‘Alex is one of the bvightest of the right

Wing, but he focuses too narrowly on proper-

ty and is tere on affirmative action and

other civil rights. I would hate to see him on

the Supreme Court, where he could do some

really serious damage. [don't know if our

ffieadship could withstand that.”

Were Korinski nominated for the Court by

«a Republican president backed by a Repub-

lican Senate, cis fir fom certain he would be

confirmed. Culturally iberarin while polit-

cally conservative, Kozinsl isbalanced along.

the fault line dividing the GOP Whether he

could woo both camps is not clea, but he

seems determined to try: Only balf joking’

Kozinski is the founder and sole member

‘of his own advocacy group, OOPPSSCA—

the Organization of People Patiently

Secking Supreme Court Appointment.

rounded by lavish flower gardens

and carefully manicured lawns, the

peach-colored stco Pasadena cour

of appeals building looks more hike

the vacation resort once was than a

place where layers and judges meet to battle

overthe ate ofthe acted Teas usual—a

loriously sunny day in southern Califor

snd Kozinsl is showing me the magisterial

views fom his enormous, window-wrapped

ofc. The walls ae covered with oficial doc

‘uments from his presidential appointments,

punctuated by photographs of Supreme

Cou justices and Ronald Reagan. In one

2s cece

‘omer stands a postr from the Spencer Tracy

film Inkeie the Wind—a monic that has 9

‘prominent place on the “KER” (Kozinski’s

Bavorite Flicks) ist, whieh the judge urges

fon me while he oversees every detail of the

preparation of our eoflee and bagels

A blue of activity, Kozinski is

pathologically charming and helpful. Piece

by piece, he offers up artifacts From his hile

videos of him snowboarding and bunge

jumping with his wife and three children;

hundreds of opinions, book reviews,

speeches and articles; lists of the books on

tape he listens to while driving to work; the

program and pictures from his soo's bar

‘mivavah; the phone numbers ofall his past

clerks, a5 well as of half the judges in the

country. He points to one name, chuckling.

“Make sure to call him—he really hates

sme." Forget paper tails—Kozinski is fol-

lowed by a superhighway of information.

Kozinski was so

outraged by Jane Fonda's

stance on Vietnam,

he boycotted Barbarella

Even at9 AM, the judge's chambers are

buzzing with setviy as his clerks —who are

‘on 24-hour call and frequently spend entice

nights responding to faxes sent from home

by their insomniac boss—wandercasuallyin

and out, trading snippets of legal gossip and

consulting about eases, "T realize that they

hhave to eat and sleep, although I'm not hap-

fy about it,” he says with mock indignation.

‘The judge is a famously demanding boss,

and it is not unusual for « decision (0 go

through 40.0r50 versions. “My dissent in the

libel ease against [New Yorker writer] Janet

Malcolm was very complicated, so ve had to

ddocighty-thrce drafts,” he notes offhandedly,

His clerks are reputed to be among the best-

‘rained lawyers in the country and regularly

move on to plum jobs clerking for justices,

including Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy

and Sandra Day O'Connor

Leaning back in an oversize leather chai,

Kozinski forms a steeple with his hands,

switches into a lecturing tone—wvhich he

drops shen he gets excited—and launches

into a: monologue about the kind of society

he's tying to create through his opinions:

“Look, we have o realize that ideas havecon-

sexquences, and legal ideas have more serious

consequences for society than most.” The

las in his view, hasan ineradicable moral

‘mension that we ignore at our peril. When,

for example, “courts tell us that someone else

is always to blame for whatever misfortune

happens to befll us, pretty soon we start to

belive ita denial of personal responsibil

ty that Kovinski devides with his Toyota

Principle (oamed for the company’s “You

asked for it, you got it” ad campaign),

“Lawyers must see the aw as“ method forre-

solving legitimate disputes rather than 2

‘means of extortion.” Kezinsks concern for

the creation of an ordered community tem-

pers his lisse-fuie approach to economic

‘and socal issues. Thus, in Layman. Combs,

heblasted profesional investors who reneged

fon a contract, “These weren't mom-and-pop

investors who mortgaged their retirement to

‘buy palladium mines in Zanzibay,” he wrote

“Ifthese subscribers can'tbe held tothe terms

ofthe contract they signed, who ever can?

“In an older legal tradition,” Kozinski ex

plains, “lawyers were primarily crusted ad-

visers who offered clients their wiscdom;

they advised their lients about long-term

interests, not just the problem at hand

‘Sometimes a lawyer might tell you that you

shouldn't ste because itis more important

tofind yourself the right kindof help than it

isto get money for your injury.

Fis remedy for “hate crmnes” exemplifies

this ant-ltigious, communitarian approach,

“Ou focus on paiishing the speaker dives

attention rom. the things we can do to re=

pair the damage,” he argues. Society’ first

responsibil, Korrinski says, is w reassure

vietims of thie rightful place in the commu

to tell ther that, despite the wrong suf

fered, they are not outcasts Asan illustration,

he points to the token war reparations

mother sill receives from Germans, which,

she values asa symbol oft citizens’ respon:

sibility for crimes against the ews.

Indeed, Kozinskt isnot shy aboutbringing

hie experiences to bear on hie legal formula

tions, He particulaey auinbutes his sensitiv

ty to fee speech and defendants’ rights to his

time in Romania. “I know what it means for

police realy to run amok,” he says. "Seeing

people hauled away in their pajamas in the

‘middle ofthe night stays with you.”

he grandson of a sivovitz bootlegger

and a grocery store owner, Kozinski

was born in Bucharest on Tuly 23,

1950, His fithes, Moses, spent most

of World War I in the ‘Tansnistsia

concentration camp, where inmates were

systematically worked 1o death. His mother,

Sabine, survived the war in a Jewish ghetto,

and met Moses in Bucharest in 1946, A

‘weaver by trade, and a Communist agitator

Wise Guy

ced a real skill co fall back on in case of a

catastrophe. But L was terrible at math and

Ina less than a C average

ovinski was more diligent in hisextracur-

ticular Tie: He began dating seriously and

xwrote a column in the Daily Brain, holding,

fom on everything from libertarian polities

te the graft in campus bathsooms. It was

1968, and as rallies against the Vietnam War

scaled, Kozinsli, who had just become a

naturalized citizen, chafed a his fellow stu-

‘dens’ polities, “Most ofthe protests were real-

ly about people justifying the fac that they

were chicken,” he says. “Students were se-

dduced by alltheanti-American rhetoric, They

hnadn’tlived under truly repressive regime”

‘So outtaged) by anti-American seatiments

was Kozinski that he boycotted (and still

fuses to ee) Jane Fonda movies —a stance

shout which he has only one regret “I wish

Thad seon Barbarella,” he says wistfully

"Maybe one day I'l watch the video—if

someone else pay’ fort

Unsuited for engineering or medicine, he

decided 10 cy his hand at law He squeaked

into UCLAS School of Law, where his casual

attitude toward work changed after he read

fan article that painted bleak picture of the

legal job market. “It std that ifyou were in

the top ten percent of the clas, you could

swrite yourown ticket. But ifyou weren' they

suggested that you could become an’ PBL

agent. That scared the shit out of me. Here T

was, a lite Jewish id with an accent ig-

sured that Pd never get jabs, Sol decided that

if was going to be employable, Pd havetobe

firstin my class. Noc second or third. Firs.”

Kozinski was managing editor of the baw

review and yas indeed graduated first in a

class of 300, With these credentials, he baad

his pick of jabs. One professor, however, en-

couraged him to clerks, suggesting he tll co

Anthony Kennedy, « new Ninth Circuit

Federal appeals judge. (And now, ofcourse, a

Supreme Court justice) The tsa hititoffin-

stantly: Kovinski loved his subsequent yearas

4 clerk and applied to the US. Supreme

Court for another clerkship, where he wa

eventually hired by Chief Justice Warten

‘Burger. Work had become hie pasion,

Following that clerkship, Kozinski prac-

ticed corporate law for dhe years ist in Los

Angeles snd then back in Washinggon at the

bic blooded firm of Covington & Burling

Buthe soon found that he wasn't cutout to be

a rainmaker; when the firm assigned im an

important client, Kozinski spent their entire

first meeting explaining why the cient dida’t

really have a ease. "Afr that” he says, “they

lee me stayin the law libra

Ronald Reagan was Kozinski’s salvation,

25 Coorg:

Ihe couldn't yet beon the Supreme Court,

well, for a conservative lawyer who wanted

to change the world, a post in the Reagan

administration was the next bes thing. And.

in the summer af 1980, with the hostages

stuck in Tehran and Jimmy Carter stuck in

the White House, a Reagan administration

seemed imminent, and Knzinsk's desire

eminently plausible except for one fac

He had no political experience or contacts

‘Then, while riding the Mecto t0 work one

day, he read a newspaper article titled

“Reagan's Lawyers.” As soon as Kozinski

got t his office, he called one of the lawyers

‘mentioned. “My name is Alex Kozinski”

he said in the forthright manner that had

become his trademark “I was first in my

class at UCLA, clerked for the Supreme

‘Court and want help Ronald Reagan.”

Soon enough, Kozinski was writing legal

memos for the campaign, After the clec-

tion, hie diligence was rewarded with a po-

sition in the White House Counsel's fice

Kozinski says of the

death penalty, “Once the

sentence is carried out,

the recidivism rate is low”

1 was a heady time for a conservative

young lawyer a bein Washington, Present

Reagan had brought with him a group of

Tawyersintent on rolling back liberal excesses

and deregulating the country. "It was une

liewably exciting, like storming the palace

during a South American revolution,”

Kozinski remembers, We were taking ver”

In 1981, Kozinski was made special eoun-

sel to the Merit Systems Proveetion Beard,

a Federal agency charged with, among ether

things, protecting whistle-blowers from

retribution, His time there ws marked by

turbulence; several employees were forced

‘out as the ambitious 30-year-old Reaganive

tied to reinvent a Federal bureaueracy from

the top down. Socially, however, Kozinski

fit right in, “Schmoozing and gessiping at

all those cocktail parties and receptions

‘was completely superficial,” he says with

feigned disgust. "And Iloved it.”

‘A year later, Kozinski spotted an opening:

Congress was ereating the U.S. Claims

Court, which would hear financial suits

against the government. "T called my friend

at Justice and told him, “I want to be chief

judge.” He just laughed and said, ‘Alex, you

aren't even thiry-two yet. We can’t make

you a Federal judge." Afer three months of

pestering, Kozinski received the appoint-

‘ment and was confirmed by the Senate

When a new group of Federal appeals

jndgeships were created in 1984, nobody

‘was surprised that Kozinski wanted one

Although noc yet 35, Kozinski had by this

time developed a strong group of support-

cers-who were eager to aul his name to the

growing ranks of young conserva

transforming the judiciary. But Senate

Demoerats—who were being steamrolled

while Reagan attempted @ replace more

than half the Federal beach—chose this

‘opportunity to fight back. "Their aim is

plain,” complained then senacor Alan

Cranston. “To pur the gavel of justice firm

lyin the ist ofthe New Right.”

Still, Kozinski's confirmation prospects

initially looked good: He was banlly a rigid

ideologue, and he was qualified, which led

the Judiciry Committee to send his eomina-

tion to a Senate vote with unanimous sup-

por. Then a grup called the Govemment

Accountability Project got into the set, accu

ing him of having politicized the Merit

‘Spstoms Protection Boar

Distraught by the attack, Kozinski tried

to fight back. He submitted in his defense a

radio editorial that had been broadcast on

Boston's WEEI praising him and attacking

the Government Accountability Project as

linked with anti-Semitic supporters of tee-

rorism, ‘The editorial baekired, however,

when itemenged that its writer was married

toone of Kozinski’s clerks and had consull-

ced with the judge in writing the piece

"Nevertheless, he was confirmed on a 5443

pany Tine vote. “Tm humbled,”

‘Kozinsi told the Netw York Times

hese days, Kozinski wants Amold

Schwarzenegger to play him in

enc-man, his prospective cre

play about a heroic, suit-sealing

juudge. A cross berween a “vigilante

Oliver Wendell Holmes” and “Learned

th brass knuckles,” Bench-mar is

‘Kozinskis judicial i, a postmodern super-

hhero dedicated 10 the fine art of conflict ar-

Ditration. Te is a joke, of course, but

Bench-mman is also vintage Kozinski: He is

making a serious point with humor

The morning afier he tells me about

-Benoh-man, Kozinski whisks into the smal,

‘modern courtroom of San Francisco’: US.

Gourtof Appeals, his black robes wishing,

‘mischievous smile on his face. Alkernately

offering folksy, offhand summaries of com-

plex cases and. challenging lawyers with

‘mind-bending hypothetials, Kozinshs has a

Hand

in his youth, Moses was made viee-prescent

cof a textile factory when the Soviet-backed

_zoveiniment took over after the war

Life in postwar Romania was not easy for

the Kovinskis, even with Moses's party exe

lentils. Nor was the gulf berween commu-

nisms theory and its reality lost on Alex: At

age eight, the boy got his father into trouble

by publidly asking him how a govenment

with so many political prisoners could poss-

bly publish a newspaper called Free Romania

"Thereafier, Moses use hand signals to indi.

‘cate when Alex should keep quiet

A difficult life became even harder when

the Kozinskis applied to leave Romania in

1958, Moses was immediately fired from

his executive position and sent back to the

looms; Sabine lost her job as a government

typist and was reduced to taking dictation

at home. “She would type on a small

portable typewriter with three fingers,”

Kozinski remembers. “She made eight

copies of each page and I would stack the

carbons for her. We were so poor that every

afternoon, Fd melt the graphite in the sun

0 she could use them again.

Permission to eave was finally granted in

1W6l. Allowed only one suitease each, the

Kozinskis arrived in Vienna on Christmas

Day and spent the next ten months debating

whether to settle in Israel or the United

‘States. Aer visting relatives in Tel Avy Alex

‘was desperate o goto Israel, bur Moses, fear=

fil about the wars he knew his son would

have to fight there, decided on Amesca. To

rmollify his distraught son, he promised two

things: They could go to Issel if ie in the

US. didn’t work out, and upon arriving in

America, Alex would get his own television

“One taste of chocolate and bubble gum

and [was capitalist,” remembers Kozinski

T spent the first several years glued to the

television, sucking up American culeare.”

The Kozinskis had always been firm be-

lievers in the importance of education, and

in Baltimore, asin Bucharest, Alex was sub-

ject to a series of language and music

lessons. "My mother told me that every

thing you learn is another weapon in the

battle for life.” Sabine attached a wai

typical of Holocaust survivors

mediocre, don't stand out, don’t be differ

‘ent-or something might happen to you."

‘Alex was happy to comply: “Inever studied.

[followed her instructions to the letter.”

Five years alter coming to Baltimore, the

family moved to Los Angeles, where

‘Moses opened a small grocery store. After

high school, lex enrolled at UCLA to

study engineering, “My parents pushed me

into i,” he says, “They believed you need-

No RESEMBLANCE WHATSOEVER,

Auuilable 01 CD and Casese from Giams Records

(81995 Gi Rear

Sia.

Special

_ Edition

203

courtroom demeanor informed by playful

borscht-ele humor. But beneath the come

dy, Kozinshi keeps the litigants focused on

the fundamental issues at hand, probing

weaknesses witha surgeon's skill

In one of this morning's cases—against

a bookkeeper accused of absconding with

company funds—Kozinski wants to know

‘mony. The hookekeeper's defense is that she

simply botched the numbers. The proseeu-

tion argues that she was corrupt rather than

incompetent. "The whole ease comes down

to this question,” Kozinski concludes, “Wis

the bookkeeper confused, or was she el?

‘The proscentor breathes a sigh of rele:

‘The bookkeeper, it seers, had managed the

bbooks well enough until the money's disap-

pearance, so surely “confused” isthe wrong,

answer. But with his nest question,

Kozinski gently hegins to tug at a thread

that could unravel the prosecution's case

“L guess i all boils down to the issue of

whether beingan accountant iean essential

characteristic or not. Let's say we had

something like a DNA test, where you

could take a blood sample and say: Yap,

that’s a bookkeeper, of, that’s not a book

keeper Then our problem would be saved,

‘wouldn’cit?” Kozinski asks pointedly.

The prosecutor shifts nervously fom foot

to foot. If he pursues Kozinska’s analoy

hell be forced to admit that—ualike with

Fingerprints or DNA—there is no scientific

method with which to tell the difference be-

tsvecn a bad bookkeeper and a dishonest

‘one, But fhe admits that, he discredits his

‘expert witness. So the prosecutor dodges

Kozinski's question. “But, uh, then that

‘would be a diflerent case,” he offers lecby.

“Ofcourse itis different ease,” Kazinski

says testy, “but iF yon answer my question,

Tl show you how the two are relate.”

Tn an attempt to delay the inevitable, the

prosecutor switches the subject and stam

mers on fora few minutes about other ix

sues before slinking back to h

Rejuvenated, the defense springs up for his

rebuttal, apparently confident chat Kozin

ski as swung the ease his way.

Remember,” cautions the judge, luxur-

antlycoling his Transylvanian 1s, “eases are

‘more alien loscthan won on rebuttal.”

‘Stunned by Kozinsk’s bluntness, the de-

fense lamyerstandk silent fora few seconds."

take that into consideration,” he says meekly

and sts down without utering a word. The

‘entire courtroom dissolves into laughter

thong

Kozinski brings a certain

informality to the courtroom, his

constitutional philosophy—the

compass guiding his vast array of

decisions —is anything bot lax. It

revolves, he explains, around thrce pring

ples: textual fidelity (interpretations

should be grounded in the actual words of

the Constitution), completeness (provi

sions in the Constitution should not be is-

nosed or emasculated) and consistency

(similar phrases should be construed in

similar ways). “The Constitution is com

plicated, old

thar is meant to have some play in the

joins,” he says. “Buc ie must have limits to

ad multilayered document

its interpretation or else you are simply

taking advantage of its flexibility for your

‘own purposes, You ean’ just find anything

you want co find ini.”

There are some, however, who believe

Kozinski applies his intezpretive principles

in as inconsistent a fashion as the liberals

he criticizes. “I don’ think i is possible 10

ict theory of constitutional

interpretation,” says University of South-

ern California lav

Chemerinsky. “Kozinski follows his theo

have such

professor Erwin

Fics ia some areas and not in others. His

Volumes One and Two

Includes two new songs

recorded exclusively for Volume Two.

“featuring she fre single and video

Kingston Town

Wise Guy

opinions involving the takings clause [the

portion of the Fath Amendment that re-

quires that citizens be compensated when

the government “takes” or reduces the value

of their property|, for instance, tend to be

very broad and don't square at all with his

decisions involving criminal law!

“However one evaluates Kozinski’s con-

sistency his libertarian vision is having a

tremendous impact on all levels of lave in

America, from the Supreme Court to legal

textbooks. That’ not accidental: Kozinski

ffien consciously crate decisions wid

eye tovward getting them into vexthooks,

thereby bringing the next generation

of lawyers around to his views, “Those

first years of law school are very forma:

tive," Kozinski says, “and although T may

not get a hundred percent or even fifty

percent of them to see things my way, I

will get owenty-five pereent.”

‘Kozinski’s influence can also be seen in

the debate over capital punishment: When

a jury deliberated over whether to exe

cute convicted child-killer Susan Smith,

Kozinski’s writings were widely cited

Capital punishment, he argued in a much

liscussed article excespted by the New York

Times, is essentially a problem of resource

(Continued from page 201) theatrical _is

most evident to Smith in ‘wo presidential

performances that have entranced her foras

long as she can remember: One is John E,

‘Kennedy's Bay of Pigs speech and the other

is Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s fireside

chats “Tas fascinated by how someone in

1 postion of power uses language to sway

people,” marvels Smith. “With FDR, those

chats—which Pve he

ally

them very early in my interest in language

sand identity and I saw wat you have todo,

T said co mysel You have to say something

from such a profound place that it has a

music which intoxicates people.”

rd, never readies

we the rhythm ofa walezT listened to

mith often tells the story of a

feminist critic who deseribed her

acting the role of a white woman

asacritique of white women. "Up

‘until that time I'd thought that if

try to give these accurate accounts, then

that’s enough,” Smith remembers. “But I

realized that no matter what I'm doing,

the fact of my race and my gender is going.

to be really present, and once I embraced

that and stil played everybody, my work

25a Goerge.

allocation, and should be analyzed acconi-

ing to market principles: We give the death

penalty to too many people for too many

crimes and without killing enough of them,

creating a backlog that would require one

‘execution every day for 26 years to clear up.

“The death penalty isa public good we all

pay fr,” he wirote, “0 we should find out

whether we are getting our money's worth

Kozinski suggested we construct a moral

hieraechy of esl in onder to decide whom to

execute. “Everyone on death row is. ver

bad,” he wrote, “but even within that de

praved group, it’s possible 10 make moral

judgments about how deeply someone has

‘stepped down the eungs ofl.” Dismissing

arguments that innocent defendants are

sometimes put to death and that capital pun-

ishment is given disproportionately to

African-Americans, Kozinski defended its

derorent value. “Once the sentence is carsied

‘ot, the recidivism rateis low” he concluded.

Grisly sentiments like these would surely

shore up Kozinski’s conservative credentials

should he ever fae the Senate's scrutiny fora

Supreme Court appointment. But his nomi-

nation would prove a dilemma for the

Republicans: Kozinsl’s passionate defense

of First and Fourth Amendment rights

became political. As my onetime teacher,

the poet Diane Wakoski, said: ‘Your ene”

‘mies make a hero out of you.

Although she hasn't always recognized

iat the time, race has been an issue in

‘Smith's life since her early years living

with her parents and four sibli

black middle-class neighborhood in

‘more. She grew up thinking her

neighborhood hal never been different,

“You have to say

something from such a

profound place

that it has a music which

intoxicates people”

but recently discovered otherwise. "My

parents were the first black people to move

in, They busted that block!” she says.

“Being black and middle-class is a dif.

ferent thing from white middle-class,”

Smith continues. "I's a community that's

trying to create itself as an institution at

the same time that those in it are tying 10

would give the far right reason (0 pause.

“He's too unpredictable, he isn'ta Seaia ora

Thomas, says New York University law pro-

fessor Stephen Gilles. "Kozinsli is a truly

independent thinker, and we are ata point

where presidents want only ure things.”

Kozinsk is perfectly happy on the Ninth

Cineuit he insists. "Besides i'm running for

a seat on the Coust 'm probably not doing it

the right way,” he says, “Pm not saying that T

haven'tthougheaboutit,butifT censored my-

self in hopes of influencing a confirmation

hearing that probably won't ever happen, Pa

be Kimiting myself erly: Here on the Ninth

Gieuit Fan think about legal issues lke a

professor. Iewould bea shame to give that up

alli the name of sme vain hope.

Lofiy sentiments indeed. ‘The judge cer

tainly seems content with his if on the na-

tion's second highest court—safe from lizmus

texs and probing senators. Bur might this be

ploy, the subtle political ruse of announcing

your don't want a jab inthe hopes of thereby

bettering your chances of geting it? “Okay” T

ask him, “iFyou're not running forthe Cour,

then where do you stand on Roe Made?”

Kozinla’s eyes dart back and forth."Well,

you see’ hesays,an enormous, sy grin taking

‘over his ace, “Te never sead it?” c

get away, Baltimore was very segropated. 1

knew had to getaway from it,but hadn't

realized how much my mother wanted me

to as well until I visited recently with the

ncipal of my high school, who told

sme.” Growing up asablack female in segre-

gated Baltimore, Smith fel lost. “There's

this fecling of unworthiness, and atthe same

time you're tld you're not supposed to have

feelings of unworthiness,” she remembers.

ein Baltimore through her

ens then graduated in 1971 from Beaver

ollege in Pennsylvania—at that time sn

all-female institution, naw coed, San

rancisco is where Smith says she really

‘grew up. She stayed with an aunt who had

intrigued her since childhood. “She wore

furs and had been rumored to have been

‘4 kept woman,” says Smith, What Smith

found was someone to admire: a strong

‘and wonderful married woman who, like

her, had gotten away from the nest.

Now, almost ewo decades later, Smith

stands in font of the unoccupied gra

four-story building downtown that for-

merly housed the American Conservatory

Theater. This ie where she discovered her

calling, and its clear that the place still

hholds profound meaning for her. She got

her MRA. here in 1977, when it was

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Cikkek 22.körmendinéDocument67 pagesCikkek 22.körmendinéMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- The LightcyclerDocument36 pagesThe LightcyclerMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- Relatorio Abutre - VCF PDFDocument57 pagesRelatorio Abutre - VCF PDFMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- 13 - Operational StrategyDocument5 pages13 - Operational StrategyMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- Energy Conservation in Asia PDFDocument410 pagesEnergy Conservation in Asia PDFMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- PK Book 6614Document577 pagesPK Book 6614Maria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- Codigo MaritimoDocument106 pagesCodigo MaritimoMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- Codigo PenalDocument224 pagesCodigo PenalDiego BayerNo ratings yet

- TematikaDocument2 pagesTematikaMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet