Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Uses of Diode Lasers in Orthodontics PDF

Uploaded by

monwarul azizOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Uses of Diode Lasers in Orthodontics PDF

Uploaded by

monwarul azizCopyright:

Available Formats

©2004 JCO, Inc. May not be distributed without permission. www.jco-online.

com

Clinical Uses of Diode Lasers

in Orthodontics

JAMES J. HILGERS, DDS, MS

STEPHEN G. TRACEY, DDS, MS

O rthodontists have long been challenged by

tissue problems that can occur during or after

treatment. Until now, their only viable option for

waves run parallel to one another rather than

being divergent), uniphasic (the light waves have

synchronous peaks and valleys), and intense

the more severe cases has been to refer them to (able to change the nature of targeted tissues).

the periodontist—to say nothing of the many These properties make laser light extremely

other soft-tissue discrepancies that are not signif- focused and powerful.

icant enough for referral, but do affect the final Lasers have come into widespread usage in

results, especially esthetic appearance. general dentistry in the last decade. What makes

The diode soft-tissue laser is a highly effec- the diode laser particularly applicable in ortho-

tive and predictable new device for simple recon- dontics is that its wavelength is between 800 and

touring of tissue, requiring only a topical anes- 980 nanometers—appropriate for removing soft

thetic. In our opinion, the diode laser will soon tissues, due to their pigmentation and hemoglo-

gain wide acceptance in orthodontics because of bin content. Energy from the laser is converted in

its ease of use, reasonable cost, positive patient a photothermal reaction, making it possible to

response, and impact on esthetic results. “paint away” targeted soft tissue in a controlled

and focused manner without unwanted side

effects on the surrounding teeth. Of course, there

How the Laser Works are lasers of higher wavelength and intensity that

Laser is an acronym for light amplification can target hard tissues.

by stimulated emission of radiation. Laser light A diode laser suitable for orthodontics can

has four properties that make it different from cost $8,000-15,000. Although this might seem

ordinary light: it is monochromatic (composed of expensive, the laser’s functionality and ease of

a single wavelength), columnated (the light use make it cost-effective. There are several

A B

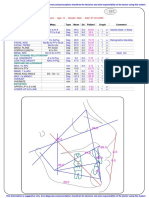

Fig. 1 A. HOYA ConBio DioDent laser, with LCD control panel, on movable cart. B. Tray setup includes pro-

tective eyewear, mirror, periodontal probe, carbon articulating paper, compounded TAC 20% topical anes-

thetic, foam applicators, and application plate with wells holding hydrogen peroxide and anesthetic. Gauze 2"

× 2" sponges saturated with water (not alcohol, which is combustible under laser light) can be used for

charred tissue debridement.

266 © 2004 JCO, Inc. JCO/MAY 2004

Dr. Hilgers is a Contributing Editor of the Journal of Clinical Ortho-

dontics and in the private practice of orthodontics at 26302 La Paz

Road #202, Mission Viejo, CA 92691; e-mail: hilgersj@hilgersortho.

com. Dr. Tracey is in the private practice of orthodontics in Upland,

CA. Both authors are certified members of the Academy of Laser

Dentistry.

Dr. Hilgers Dr. Tracey

diode lasers on the market; we have chosen the or lengthier procedures, but we have not found it

HOYA ConBio DioDent* (Fig. 1). necessary to exceed that amount.

A 400-micron optical fiber is recommend-

ed over a 300-micron fiber, which is slightly

Operative Procedure

more friable and breakable. Before each patient

To prevent unnecessary thermal degenera- use, 2-3mm should be cut off the end of the fiber

tion, the Academy of Laser Dentistry advises to avoid cross-contamination (Fig. 2). A small

using the least amount of power that can effec- cleaving stone is used to nick the fiber before it

tively accomplish a desired procedure. A setting is broken off; care should be taken to cut cleanly,

of 1 watt at a continuous pulse (as opposed to a so that the laser light source is focused rather

gated or intermittent pulse) has proved effective than dispersed. The optical fiber is then inserted

for most soft-tissue procedures. A setting of 1.25 into a plastic wand with a disposable tip for use

watts may be required with more fibrous tissues in the mouth (Fig. 3). The fiber is activated by

pulsing the laser on a dark surface such as carbon

*Trademark of HOYA Photonics, Inc., 47733 Fremont Blvd., articulating paper (Fig. 4).

Fremont, CA 94538. www.conbio.com.

The anesthetic of choice is a compounded

topical TAC 20% (Tetracaine 4%, Phenylephrine

2%, and Lidocaine 20%). The combination of the

two local anesthetics has a profound effect, while

Phenylephrine promotes local hemostasis to re-

duce systemic absorption and thus prolong the

duration of action. After the mucosal area is

dried, the peppermint-flavored topical gel is

applied to the target tissues with a Q-tip or cotton

roll and left in place for three minutes before the

laser procedure is initiated. Its peak effect will

Fig. 2 Before each patient use, 2-3mm on end of

optical fiber nicked with small cleaving stone and

cut off cleanly.

Fig. 4 Optical fiber activated by tapping it lightly

Fig. 3 After cutting, plastic wand with new dispos- on dark surface. Small holes on carbon articulat-

able tip fitted over optical fiber for use in mouth. ing paper indicate laser is ready for use.

VOLUME XXXVIII NUMBER 5 267

A

B

Fig. 6 A. Periodontal probe used to measure

depth of gingival sulcus. Bone sounding deter-

mines biological width, which should be at least 2-

3mm. B. Pinpricks made in tissue with tip of perio-

Fig. 5 16-year-old female patient with impacted dontal probe indicate precise amount of tissue to

upper left cuspid that had been brought into posi- be removed.

tion. Redundant tissue at cervical cuff did not

diminish after several months of treatment, and

root positions create esthetic asymmetry that is

apparent in patient’s smile. cation of the amount of tissue to be reduced (Fig.

6B).

The vaporization and removal of target tis-

occur within six minutes and last a minimum of sue is referred to as “ablatement”. Safety goggles

20-30 minutes. are imperative for patients, surgical staff, and any

When recontouring numerous anterior observers to prevent inadvertent exposure to

teeth, particular attention should be paid to the reflected energy or stray light (Fig. 7A). These

overall smile line. Many patients have an asym- goggles are not sunglasses, but wavelength-spe-

metrical tissue drape (Fig. 5). The most attractive cific eyewear manufactured especially for laser

smiles show 100% of the anterior teeth, although light. The near-infrared laser light is not visible

1-2mm of gingival display is generally not dis- to the operator; the visible red-wavelength light

pleasing. The zenith, or highest point of contour, is an aiming beam that indicates where the laser

of the tissue on the tooth should be slightly distal is being focused.

to the center of the long axis. Laying dental floss The diode laser is activated with a foot

across the height of the tissue contours can be pedal. The operator gently moves the fiberoptic

helpful in evaluating a gingival smile line. wand over the target tissue, using a light brush

A periodontal probe is used to measure the stroke to “paint away” the desired amount of tis-

depth of the sulcus (Fig. 6A). A biological width sue (Fig. 7B). The tip is held at a slight angle to

of at least 2-3mm, as determined by bone sound- provide a beveled, natural contour, instead of an

ing, should normally be maintained, but as little abrupt ledge. Care should be taken to avoid

as .5mm of tissue will regenerate over time. excessive contact, which might cause unwanted

Scribing a line with pinpricks of the periodontal collateral damage. An assistant should hold an

probe will help the operator maintain the appro- aspirator at the ablatement site to remove charred

priate biological width and provide an exact indi- tissue and associated odors.

268 JCO/MAY 2004

A

B

B

Fig. 7 Diode laser tissue ablatement procedure.

A. Operatory team and patient wear wavelength-

specific protective goggles. B. Assistant holds

aspirator close to target tissue to remove charred

tissue and odors. Red light is aiming beam that

indicates where invisible laser light is focused.

C

Fig. 9 Patient seven days after ablatement. Com-

posite veneer was added to facial surface of cus-

pid immediately after laser procedure. Note

improved occlusion and esthetic balance in

Fig. 8 Ablatement area cleaned with hydrogen patient’s smile.

peroxide to remove charred tissue.

After the laser procedure is completed, a ultrasoft toothbrush to use while the surgical site

cotton pledget soaked in hydrogen peroxide is is healing. Gentle brushing will promote healing,

used to debride the area of charred tissue, allow- but the patient should be made aware that some

ing the clinician to check the shape and bevel of light post-operative bleeding is not unusual for

the gingival cuff (Fig. 8). Although most patients several days after the procedure. The diode laser

report almost no pain, an over-the-counter pain is especially effective at killing bacteria at the

medication such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen surgical site, which also promotes effective and

is recommended. The patient should be given an rapid healing (Fig. 9).

VOLUME XXXVIII NUMBER 5 269

Clinical Uses of Diode Lasers in Orthodontics

A

Fig. 10 A. 13-year-old female patient showing un-

even crown display, especially in maxillary central

incisors, after orthodontic treatment. B. Improve-

ment in tissue drape immediately after diode laser

surgery. C. Post-operative healing six weeks later.

C C

Clinical Uses of the Diode Laser appliances are removed, gingival swelling sub-

sides, and oral hygiene improves. Occasionally,

1. Gingival Recontouring and Sculpting (Fig. 10) however, the tissue levels will not align properly

Orthodontic tooth movement often creates due to the distance of tooth movement, root posi-

uneven tissue levels. The tissues will normally tions, hormonal changes, periodontal response,

adjust to the reconstituted bone heights once the or poor hygiene. This problem is especially unat-

270 JCO/MAY 2004

Hilgers and Tracey

A A

B B

C C

Fig. 11 A. 44-year-old female patient with low and Fig. 12 A. Five months after space creation, upper

thick frenum attachment resulting in diastema. right cuspid had not broken through gingival tis-

B. Frenum removed with diode laser. C. Healing 22 sue. B. Access gingivectomy performed with

days later, with little post-operative discomfort. diode laser. C. Bracket placed and wire engaged

immediately after surgery.

tractive in the upper anterior teeth. Sculpting or require removal of fibrous interseptal tissue

reshaping the tissue once swelling has subsided should be referred to the periodontist, simple

can create a more pleasant smile and improve frenum removal is well within the capability of

periodontal health where residual gingival hyper- the diode laser.

trophy exists.

3. Access Gingivectomy (Figs. 12,13)

2. Frenectomy (Fig. 11)

When a tooth resists eruption, with a thin

Although complex frenectomies that layer of tissue covering its surface, treatment can

VOLUME XXXVIII NUMBER 5 271

Clinical Uses of Diode Lasers in Orthodontics

A A

B B

C C

Fig. 13 A. 12-year-old female patient with incom- Fig. 14 A. 12-year-old female patient showing

pletely erupted peg lateral incisors preventing hypertrophy of tissue around brackets. B. Excess

bracket placement. B. Access gingivectomy per- tissue removed with diode laser. C. Healing two

formed with diode laser. C. Brackets in place. months later, demonstrating marked improvement

in tissue health and esthetics.

be delayed for months. One of the most common

uses of the diode laser is for the removal of tissue orthodontic brackets, inhibiting hygiene and

covering unerupted teeth. Ablatement of such tis- slowing tooth movement. Even prodigious tooth

sue should be performed judiciously, so that the brushing may not be enough to make this excess

tooth is exposed only to the extent needed to tissue recede, and the orthodontist has had few

place a bracket. The diode laser vaporizes the tis- options short of appliance removal. The diode

sue without bleeding, allowing the tooth to be laser can quickly and easily remove swollen tis-

etched, sealed, and bonded. Once the exposed sue without undue patient discomfort.

tooth has been erupted sufficiently, more excess

tissue can be removed.

5. Operculum Removal (Fig. 15)

4. Gingivectomy of Hypertrophic Tissue (Fig. 14) Another common laser procedure is the

removal of the operculum covering erupting

Hypertrophic tissue can swell around teeth. This tissue can inhibit band or bracket

272 JCO/MAY 2004

Hilgers and Tracey

A

Fig. 15 A. 15-year-old male patient with operculum covering distolingual aspect of lower left second molar.

B. Operculum removed with diode laser. C. Placement of bonded buccal minitube immediately after surgery.

placement, slowing treatment. REFERENCES

1. ANSI Z136.3 (1996) Safe Use of Lasers in Health Care Facili-

6. Other Uses ties, Laser Institute of America, Orlando, FL, 1996.

2. Bar-Am, A.; Lessing, J.B.; Niv, J.; Brenner, S.H.; and Peyser,

Preparations for veneers and treatment of M.R.: High- and low-power CO2 lasers: Comparison of results

aphthous ulcers and herpetic lesions have also for three clinical indications, J. Reprod. Med. 38:455-458,

1993.

shown promising responses to the diode laser. 3. Catone, G.A. and Alling, C.C.: Laser Applications in Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery, Saunders, Philadelphia, 1998.

4. Coluzzi, D.J.; Rice, J.H.; and Coleton, S.: The coming of age

Conclusion of lasers in dentistry, Dent. Today 17:64-66, 1998.

5. Fitzpatrick, R.E.; Ruiz-Esparza, J.; and Goldman, M.P.: The

As orthodontists become increasingly depth of thermal necrosis using the CO2 laser: A comparison

focused on esthetics, new tools that can greatly of the superpulsed mode and conventional mode, J. Dermatol.

Surg. Oncol. 17:340-344, 1991.

improve the quality of their treatment results are 6. Frentzen, M. and Koort, H.J.: Lasers in dentistry: New possi-

becoming available. Clinicians are finding diode bilities with advancing laser technology? Int. Dent. J. 40:323-

laser soft-tissue ablatement to be an amazingly 332, 1990.

7. Gutierrez, T. and Raffetto, N.: Managing soft tissue using a

simple procedure. Advantages of diode laser laser: A 5-year retrospective, Dent. Today 18:62-63, 1999.

therapy in orthodontics include: 8. Mercer, C.: Lasers in dentistry: A review, Part I, Dent. Update

• Single-appointment procedure, using only a 23:74-80, 1996.

9. Moritz, A.; Gutknecht, N.; Doertbudak, O.; Goharkhay, K.;

topical anesthetic, with little pain or bleeding. Schoop, U.; Schauer, P.; and Sperr, W.: Bacterial reduction in

• Cost-effective for both patient and practice. periodontal pockets through irradiation with a diode laser, J.

• Reduces treatment time. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 15:33-37, 1997.

10. Pick, R.M. and Colvard, M.D.: Current status of lasers in soft

• Vastly improves esthetic results. tissue dental surgery, J. Periodontol. 64:589-602, 1993.

• Enhances the practice’s high-tech image. 11. Polanyi, T.G.: Laser physics: Medical applications, Otolaryn-

We highly recommend that any orthodon- gol. Clin. N. Am. 16:753-774, 1983.

12. Rowson, J.E.: The contact diode laser: A useful surgical instru-

tist interested in pursuing diode laser surgery ment for excising oral lesions (abstr.), Br. J. Oral Maxillofac.

attend a one-day accreditation program, spon- Surg. 33:123, 1995.

sored by the Academy of Laser Dentistry, which 13. Taylor, J. and Dickerson, W.G.: Case reports: Lasers in soft-tis-

sue management, RDH 19:41,71, 1999.

is offered frequently at various U.S. locations. 14. Walsh, J.T. Jr. and Deutsch, T.F.: Pulsed CO2 laser tissue abla-

tion: Measurement of the ablation rate, Lasers Surg. Med.

8:264-275, 1988.

15. Wilder-Smith, P.; Dang, J.; and Kurosaki, T.: Investigating the

range of surgical effects on soft tissue produced by a carbon

dioxide laser, J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 128:583-588, 1997.

VOLUME XXXVIII NUMBER 5 273

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Preparation: Self-Paced Scripting in Servicenow FundamentalsDocument5 pagesPreparation: Self-Paced Scripting in Servicenow FundamentalsCrippled SoulNo ratings yet

- Therm Coal Out LookDocument27 pagesTherm Coal Out LookMai Kim Ngan100% (1)

- ABO Case Report Work File PDFDocument9 pagesABO Case Report Work File PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- A 3D Computer Aided Design System Applied To Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthodontics PDFDocument12 pagesA 3D Computer Aided Design System Applied To Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthodontics PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Ricketts Analysis: Max. PositionDocument1 pageRicketts Analysis: Max. Positionmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Investigation of The Efficacy of Low Lavel Laser PDFDocument9 pagesA Clinical Investigation of The Efficacy of Low Lavel Laser PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- 9 Didactica MaestrosDocument6 pages9 Didactica MaestrosCalderon RafaNo ratings yet

- Cellular Effect Related To The Clinical Uses of Laser in Orthodontics PDFDocument5 pagesCellular Effect Related To The Clinical Uses of Laser in Orthodontics PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Buccal Corridor PDFDocument6 pagesBuccal Corridor PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Clinical Effect of CO2 Laser in Reducing Pain in Orthodontics PDFDocument5 pagesClinical Effect of CO2 Laser in Reducing Pain in Orthodontics PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Cellular Effects Related To The Clinical Uses of Laser in OrthodonticsDocument5 pagesCellular Effects Related To The Clinical Uses of Laser in Orthodonticsmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- MBT Versatile Bracket Placement Guide Ifu PDFDocument1 pageMBT Versatile Bracket Placement Guide Ifu PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Laser Debonding of Ceramic Brackets PDFDocument5 pagesLaser Debonding of Ceramic Brackets PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- The Ricketts Analysis Uses The Following MarkersDocument2 pagesThe Ricketts Analysis Uses The Following Markersmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Bcoe Examinee Worksheet PDFDocument1 pageBcoe Examinee Worksheet PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Dental Orthodontic Technology Rem F1MA34 PDFDocument10 pagesDental Orthodontic Technology Rem F1MA34 PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Clinical Effect of CO2 Laser in Reducing Pain in Orthodontics PDFDocument5 pagesClinical Effect of CO2 Laser in Reducing Pain in Orthodontics PDFmonwarul azizNo ratings yet

- Stet 2023 (Computer Science) Full Form: Programming Learning Center Search On Youtube:-@plc - SD Like and SubscribeDocument7 pagesStet 2023 (Computer Science) Full Form: Programming Learning Center Search On Youtube:-@plc - SD Like and SubscribeShiv KantNo ratings yet

- De La Salle University College of Business Course Checklist: Basirec SystandDocument2 pagesDe La Salle University College of Business Course Checklist: Basirec SystandncllpdllNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Deep Learning-Based Real-Time AI Virtual Mouse System Using Computer Vision To Avoid COVID-19 SpreadDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Deep Learning-Based Real-Time AI Virtual Mouse System Using Computer Vision To Avoid COVID-19 SpreadRatan teja pNo ratings yet

- Updating The Network Controller Server CertificateDocument4 pagesUpdating The Network Controller Server CertificateNavneetMishraNo ratings yet

- Jan Lokpal Bill Lok Sabha Rajya SabhaDocument4 pagesJan Lokpal Bill Lok Sabha Rajya SabhasushkanwarNo ratings yet

- Applying Lean Techniques in The Infrastructure Project: Jubail Industrial City, Suadi ArabiaDocument20 pagesApplying Lean Techniques in The Infrastructure Project: Jubail Industrial City, Suadi ArabiaYogesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- TTD's Role in EducationDocument37 pagesTTD's Role in Educationsri_iasNo ratings yet

- Precision Agriculture Using LoraDocument22 pagesPrecision Agriculture Using Loravrashikesh patilNo ratings yet

- FINANCE CASES AND TOPICSDocument7 pagesFINANCE CASES AND TOPICSFuzael AminNo ratings yet

- Labour Welfare Management at Piaggio vehicles Pvt. LtdDocument62 pagesLabour Welfare Management at Piaggio vehicles Pvt. Ltdnikhil kumarNo ratings yet

- 231025+ +JBS+3Q23+Earnings+Preview VFDocument3 pages231025+ +JBS+3Q23+Earnings+Preview VFgicokobayashiNo ratings yet

- Posteguillo The Semantic Structure of Computer Science Research ArticalsDocument22 pagesPosteguillo The Semantic Structure of Computer Science Research ArticalsRobin ThomasNo ratings yet

- Kamor Ul Islam Jakoan Kobir Riad Omar Faruk Iqramul Hasan MD Abdur Rahman MD Kamrul Hasan FahimDocument16 pagesKamor Ul Islam Jakoan Kobir Riad Omar Faruk Iqramul Hasan MD Abdur Rahman MD Kamrul Hasan FahimRezoan FarhanNo ratings yet

- CAO 2018 T3 Question PaperDocument2 pagesCAO 2018 T3 Question Paperharsh guptaNo ratings yet

- Cisco CallManager Express 10Document8 pagesCisco CallManager Express 10Bryan GaviganNo ratings yet

- Purpose: IT System and Services Acquisition Security PolicyDocument12 pagesPurpose: IT System and Services Acquisition Security PolicysudhansuNo ratings yet

- Top Triangle Bikini Kinda PatternDocument5 pagesTop Triangle Bikini Kinda PatternVALLEDOR, Dianne Ces Marie G.No ratings yet

- BCA IV Sem Open Source TechnologyDocument4 pagesBCA IV Sem Open Source TechnologyKavya NayakNo ratings yet

- Principles of BioenergyDocument25 pagesPrinciples of BioenergyNazAsyrafNo ratings yet

- BIR Rule on Taxing Clubs OverturnedDocument2 pagesBIR Rule on Taxing Clubs OverturnedLucky JavellanaNo ratings yet

- Lasco v. UN Revolving Fund G.R. Nos. 109095-109107Document3 pagesLasco v. UN Revolving Fund G.R. Nos. 109095-109107shannonNo ratings yet

- Soil Fabric LoggingDocument4 pagesSoil Fabric LoggingCaraUnggahNo ratings yet

- FINAL REPORT (L ND M)Document84 pagesFINAL REPORT (L ND M)MuzamilNo ratings yet

- 5TH International Conference BrochureDocument5 pages5TH International Conference Brochureanup patwalNo ratings yet

- Thar Du Kan Calculation Report-13.02.2020 PDFDocument141 pagesThar Du Kan Calculation Report-13.02.2020 PDFZin Ko LinnNo ratings yet

- Multi-User Collaboration With Revit WorksetsDocument10 pagesMulti-User Collaboration With Revit WorksetsRafael Rafael CastilloNo ratings yet

- SC Judgment-Second AppealDocument29 pagesSC Judgment-Second AppealNarapa Reddy YannamNo ratings yet

- Brochure Thermoformer Range enDocument52 pagesBrochure Thermoformer Range enJawad LOUHADINo ratings yet