Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reading 2 Álvarez&Michelson Lin's Festschrift Nov 1

Uploaded by

JENNIFER SANCHEZ MUÑOZ0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views31 pagesA design perspective on intercultural communication in second/foreign language

education

Original Title

Reading 2 Álvarez&Michelson Lin's Festschrift Nov 1 (1)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA design perspective on intercultural communication in second/foreign language

education

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views31 pagesReading 2 Álvarez&Michelson Lin's Festschrift Nov 1

Uploaded by

JENNIFER SANCHEZ MUÑOZA design perspective on intercultural communication in second/foreign language

education

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 31

A

design perspective on intercultural communication in second/foreign language

education

José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia, School of Language Sciences, Universidad del Valle,

Colombia

Kristen Michelson, Department of Classical and Modern Languages and Literatures, Texas

Tech University

INTRODUCTION

Developing intercultural competence among second/foreign language (S/FL) students has

long been a stated objective of S/FL education. At times this outcome has been assumed by

mere virtue of learning another language, while at others it has been more intentionally

taught and measured, through models (e.g. Byram, 1997; Fantini, 2009) and conceptual

orientations (Kramsch, 2011; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013) that have emerged from within

and beyond the field of applied linguistics. A genealogical look into these models traces

back to decades of study into the nature and inter-relationship of language and

communication, the epitome of which has been the concept of communicative competence

(CC), which has continued to dominate classroom practice since the early 70s, and has been

highly influential for models of intercultural competence (IC). Yet, the rootedness of models

of IC in historical conceptions of communicative competence poses several problems for

their actual use within S/FL classrooms. One of the principal limitations inherited from

traditional views of CC is that communication remains verbocentric, operationalized as

linguistic activity. A second concern is that communication is considered a cognitive,

individual activity, rather than a social, co-constructed, multimodal process of meaning

making. A third limitation is their focus on the learner as intercultural speaker,

downplaying processes of interpretation that take place both in face-to-face encounters

and in intercultural engagement with texts.

In the paper that follows, we explore the way in which IC frameworks, as applied to S/FLE,

constrain possibilities for pedagogy through these limitations, and through their

predominant focus on assessing individual cognitive achievement to the detriment of

guiding students in learning to perform the kind of semiotic work that takes place in every

act of communication. First, we trace the development of notions of CC and IC, highlighting

ways that IC frameworks have failed to account for the different elements that intervene in

communication processes. Next, we argue for a shift in focus from developing and assessing

intercultural competence to developing interculturality, and highlight ways in which the

S/FLE classroom is particularly well-suited to this by expanding learners’ interpretative

frameworks, and thus their semiotic resources. Finally, we draw on heuristics from social

semiotics and multiliteracies pedagogies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; New London Group,

1996) to present possibilities for reconceptualizing IC in S/FLE.

FROM COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE TO INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATIVE

COMPETENCE

During the last five decades much of the conceptual and research work in the area of

second/foreign language education (S/FLE) has spun around the concept of

communicative competence. Likewise, the concept itself has provided intellectual basis for

pedagogical activity, curriculum design, and teacher education guidelines. Despite

extensive and often controversial academic discussions begotten by the two words that

compound the term--competence and communication (Taylor, 1988; Widdowson, 1989;

Spolsky, 1989; Celce-Murcia, Dörnyei, & Thurrell, 1995; Leung, 2005; Firth & Wagner,

2007; Block, 2014, Blommaert & Rampton, 2011; Álvarez Valencia, 2018)--the term

remains dominant in the field of applied linguistics.

Hymes first introduced the concept in the early 70s as a reaction to Chomsky’s prevailing

linguistic view of competence. In Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, Chomsky (1965), evoking

the Saussurean distinction between langue (language as a system) and parole (speech),

offered his distinction between competence (the ideal speaker-listener’s knowledge of

language) and performance (the manifestation of language in concrete situations).

Chomky’s idea of linguistic competence was underlain by a monolithic view of language,

dissociated from any social context, and the priority of an idealized monolingual native

speaker was the role model for language development.

Hymes’ (1972) contribution to the understanding of communicative competence lies in the

centrality he gave to meaning and context and the way they are connected in a co-

creational and indexical dynamic with culture (Waugh, Álvarez Valencia, Do, Michelson, &

Thomas, 2013). Thus, ‘competence to communicate’ comprises not only the underlying

linguistic, social, cultural and psychological knowledge, but also the rules governing

appropriate and acceptable use of language. Hymes’ understanding of communication

transcended the traditional verbocentric and context-free views of communication and

language. Drawing on Jakobson (1960), Hymes acknowledges that in communicative

events, along with linguistic resources, interlocutors draw on other semiotic modes of

meaning making. Accordingly, an analyst should examine a communicative event as a

whole system of communication, which includes among other factors:

… the various available channels, and their modes of use, speaking, writing, printing, drumming,

blowing, whistling, singing, face and body motion as visually perceived, smelling, tasting, and tactile

sensation; (4) the various codes shared by various participants, linguistic, paralinguistic, kinesic,

musical, and other (Hymes, 1974, p. 13).

By bringing the social and the cultural dimensions into the understanding of

communicative production and broadening the purview of communication to include

semiotic modes beyond the linguistic mode, the sociolinguistic revolution--in part

championed by Hymes (1972, 1974)--articulated a dynamic view of language in use

“situated in the flux and pattern of communicative events” (Hymes, 1974, p. 12) within a

speech community. At the same time, it clearly forecasted the advent of multimodality as a

more comprehensive approach to understanding the current communication landscape

and its textual habitats (Álvarez Valencia, 2016a, 2018).

Hymes’ view of language and communication had paramount ramifications for S/FLE

where the concept of communicative competence was immediately adopted (Savignon,

1972) in such a way as to inform the inauguration of the Communicative Language

Teaching approach (Savignon, 1983, 1991; Berns, 1990; Richards & Rodgers, 2001).

However, this transfer and further recontextualization of CC in the field of language

education in the long run distorted Hymes’ original comprehension of the concept

(Widdowson, 1989; Leung, 2005). Dubin (1989) asserts that:

it is apparent that over time there has been a shift away from an agenda for finding out what is

happening in a community regarding language use to a set of statements about what an idealized

curriculum for L2 learning/acquisition should entail . . . [The concept of communicative competence]

has moved away from being a societally-grounded theory in terms of describing and dealing with

actual events and practices of communication which take place within particular cultures (p. 174, as

cited in Leung, 2005, p. 124).

One of the main consequences of the didactization of the concept of CC was the loss of its

dynamic nature and the reduction of the phenomenon of communication to the exchange of

linguistic (verbal) messages (Álvarez Valencia, 2018). Highly influenced by the structural

paradigm, the field of applied linguistics privileged a cognitive, mechanical, and

individualistic view of language and communication (Firth & Wagner, 2007). Under this

perspective, it appeared convenient to establish an object of study (language and

communication) whose principal features were its systematicity, homogeneity, stability,

and transparency. This in turn facilitated curricular/syllabus development, test

construction, pedagogical and material design which bolstered the profitable business of

S/FL teaching and learning (Crystal, 1997; Graddol, 2006).

Likewise, the concepts of CC specifically, and communication more broadly, have been

strongly informed by developments in the field of second language acquisition (SLA),

where communication has been conceptualized as a facilitator to acquire language through

the exchange of transactional messages (e.g. the interactional hypothesis) and thereby

develop a linguistic system, with little regard to social and cultural dimensions; then later

as a tool for meaning negotiation, and more recently as “as an arena for positioning the

speaker vis-à-vis the wider community” in multilingual and multicultural societies

(Eisenchlas, 2009, p. 56) where communication becomes a site where issues of power,

identity, social structure, polities, and ideologies are indexed. Eisenchlas’ discussion

provides a context in which to understand an evolution of the models of CC from more

psycholinguistic-oriented (Canale & Swain, 1980; Bachman, 1990) to sociocultural or

intercultural views of communication (Byram, 1997).

Communication and models of communicative competence

Although many consider Canale and Swain’s (1980) framework to be the first model of CC,

their proposal was indeed a reaction to various existing ‘theories of communicative

competence’ at the time (e.g. Munby, 1978) that they deemed incomplete. Canale and

Swain’s (1980) initial tripartite model, composed of grammatical, sociolinguistic, and

strategic competence, was later modified (Canale, 1983) to include discourse competence.

Canale (1983) provides a rather instrumental definition of communication stating that it is

“the exchange and negotiation of information between at least two individuals through the

use of verbal and non-verbal symbols, oral/written visual modes, and production and

comprehension processes” (p. 4). In following, to a certain extent, Chomsky’s distinction

between competence and performance, Canale defined CC as “underlying systems of

knowledge and skills required for communication” (p. 5) where knowledge referred to

linguistic information available in the brain, and skills featured an individual capacity to

use that linguistic information in actual communication. The four areas of knowledge and

skills proposed by Canale comprised grammatical competence (i.e. understanding the

code); sociolinguistic competence (i.e. appropriateness of meaning and form in relation to

contextual factors and participants); discourse competence (i.e. the capacity to design

cohesive and coherent texts); and strategic competence (i.e. the capacity to use verbal and

nonverbal communication strategies to enhance effectiveness in communication, including

compensating for communication breakdowns).

Canale’s (1983) model presents an important conceptual improvement from that of Canale

and Swain (1980) in that the former acknowledges the role of nonverbal communication

that had been previously omitted. Yet, Canale’s (1983) proposal locates nonverbal

communication primarily in the sociolinguistic and strategic components of communicative

competence. Although this is an important step in recognizing the multimodal nature of

communication, this modular understanding of CC and particularly nonverbal

communication overlooks the fact that communication is an embodied (i.e. expression of

the body) manifestation of human experience (Wachsmuth, Lenzen, & Knoblich, 2008).

This omission is clearly observed in the way discourse competence is defined, which is

limited to the use of verbal devices to design unified texts (Canale, 1983). This definition

misses the point in so far as that in interactional exchanges speakers combine features of

nonverbal communication such as gesture, gaze, touch, and spatial distribution to create

discursive coherence and cohesion. In fact, the creation of coherence and cohesion in

interactive exchanges relies heavily “on the presence of an expressive body and its relation

to objects and other expressive bodies” (Wachsmuth, Lenzen & Knoblich, 2008, p. 3).

Bachman (1990), and later Bachman and Palmer (1996) proposed and refined their own

models of CC. Although initially conceived for the area of language testing, their model has

gained currency and has also informed language teaching and curriculum development.

Evoking Eisenchlas (2009), Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) model focuses on language use

(instead of communication) defined “as the creation or interpretation of intended

meanings in discourse, or as the dynamic and interactive negotiation of intended meanings

between two or more individuals in a particular situation” (pp. 61-62). Notice, though, that

despite being presented as a model that emphasizes language use, it draws heavily on

cognitive theory, judging from the two broad areas that comprised what they termed

‘communicative language ability’: language knowledge, or “a domain of information in

memory” (Bachman & Palmer’s, 1996, p. 67) and strategic competence, or “a set of

metacognitive strategies” (p. 67).

Within language knowledge are organizational knowledge and pragmatic knowledge,

where the former integrates Canale’s (1983) grammatical competence and discourse

competence, now termed grammatical knowledge and textual knowledge, respectively.

Grammatical knowledge involves knowledge of vocabulary, syntax, phonology and

graphology that contribute to recognition and creation of grammatically correct sentences.

Textual knowledge, on the other hand, includes knowledge of cohesion and of elements of

rhetorical and conversational organization.

Unlike Canale’s (1983) model, Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) proposal highlights the role of

pragmatics in communication. For the latter, pragmatic knowledge is the users’ capacity to

produce language related to their communicative goals and which is appropriate in a

particular context of language use. Pragmatic knowledge incorporates functional

knowledge (i.e. a user’s ability to produce utterances or sentences connected to their

communicative goals and in relation to an interlocutor’s intentions, as well as knowledge of

different functions of language that allow speakers to express and understand experience,

manipulate, create, and establish relationships (ideational, manipulative, instrumental, and

imaginative functions), and sociolinguistic knowledge. Sociolinguistic knowledge

broadened the description rendered in Canale’s model and incorporated dimensions such

as awareness about dialects of varieties, registers, idiomatic expressions, cultural

references and figures of speech that enable users “to create or interpret language that is

appropriate to a language use setting” (Bachman & Palmer, 1996, p. 70).

Drawing on Faerch and Kasper’s (1983) psycholinguistic model of language production,

Bachman (1990) and Bachman and Palmer (1996) describe their second component--

strategic competence--as a set of metacognitive strategies that enable cognitive

management in language use. Strategic competence operates by combining the elements of

user involvement in goal setting, assessment of communicative resources, and planning of

language use. Different from Canale and Swain (1980) and Canale’s (1983) strategic

competence which related more to users’ socio-interactive strategies to solve

communicative breakdowns, this newer understanding of strategic competence focused

more on users’ cognitive and affective mechanisms that could be used either in interactive

communication or in other contexts of discourse comprehension, such as reading a novel.

Although Bachman (1990) and Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) models are considered to

have provided a more comprehensive understanding of communicative competence than

Canale and Swain’s (1980) and Canale’s (1983) models, in our view the models fall short of

acknowledging the multimodal nature of communication and results in legitimizing a

verbocentric view of communication. Communication is reduced to ‘language use’ and

dimensions such as nonverbal communication are outright eschewed. In referring to

Canale’s (1983) definition of strategic competence, Bachman (1990) states: “these

definitions include non-verbal manifestations of strategic competence, which are clearly an

important part of strategic competence in communication, but which will not be dealt with

in this book” (pp. 100-101).

Prompted by the lack of direct relationship between models of CC and objectives of

language instruction, Celce-Murcia, Dörnyei, and Thurrell (1995) proposed a ‘pedagogically

motivated model’ of communicative competence to inform Communicative Language

Teaching. The major emphasis of this model is discourse competence, which establishes a

relation of co-creation with sociocultural competence (knowledge of how to communicate

in accordance with social and cultural contextual conditions), linguistic competence,

(knowledge of lexico-grammatical elements) and actional competence (the capacity to use

speech acts and speech acts sets in conveying and understanding communicative intent).

Another component is strategic competence, which follows Canale and Swain’s (1980)

conceptualization in that it is the “knowledge of communication strategies and how to use

them” (Celce-Murcia et al., 1995, p. 26). As such it includes strategies to initiate, terminate,

maintain or redirect communication in the face of interactive difficulties or communication

breakdowns.

A particular strength of this model is its ability to show, theoretically, a clear

interrelationship between the different components harnessed around discourse

competence. Moreover, it provides a more detailed list of elements that comprise each

competence providing guidelines “for curriculum design, language analysis, materials

development, teacher training, classroom research, and language assessment” (p. 30).

Nonetheless, similar to other models, it falls short of specifying exactly how curriculum

designers or instructors could do so. Celce-Murcia et al. (1995) seem to expand previous

views of language and communication granting relevance to dimensions such as culture

and identity, as language is “not simply a communication coding system but also an integral

part of the individual's identity and the most important channel of social organization,

embedded in the culture of the communities where it is used” (p. 23).

Similar to Canale’s (1983) model, an asset of Celce-Murcia et al.’s (1995) proposal is that it

includes specific elements of nonverbal communication (kinesic, proxemic, haptic,

paralinguistic) within sociocultural competence, suggesting an underlying view that face-

to-face communication involves more than verbal exchanges. Nevertheless, this

perspective is reductive because it ignores other types of texts that users can create which

combine not only oral or written language but also images, artifacts and other semiotic

resources. As in the previous models, communication and CC are reduced to knowledge

and capabilities that are solely in the mind of interlocutors and not the product of co-

creation between cognitive and material resources and their affordances available in the

ecological spaces that surround communicative practices.

Of all the models presented so far, Celce-Murcia et al. (1995) forecast current interest in

intercultural aspects of interaction through their inclusion of cross-cultural awareness

within sociocultural competence. They vouch for its need because “there are so many

culture-specific do's and don't's that without any knowledge of these, a language learner is

constantly walking through a cultural minefield” (Celce-Murcia et al., 1995, p. 25). Although

the perspective underlying this statement falls within the tradition of cross-cultural studies

(Spencer-Oatey & Franklin, 2009; Hofstede, 2012) characterized by conceptualizing

cultural practice as static knowledge that allows for the creation of lists of behavioral do’s

and don’ts for intercultural teaching, the authors open the door for discussing the role of

the cultural background of interlocutors in transnational encounters, an issue that at the

time had been discussed extensively in cross-cultural psychology (Hofstede, 1991),

anthropology (Hall 1959, 1966; Hall & Hall, 1990) and business management

(Trompenaars, 1993), with little development, however, in the field of language education.

It was only in the late 1990s that the contact between members of different cultural origins

was directly addressed in the area of S/FLE by Byram (1997) who proposed a model that

was instrumental for the Council of Europe’s eventual model of CC in the Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

In 2001 The Council of Europe published the first version of the CEFR. More recently the

document has been updated to develop more detailed descriptors, and include illustrative

scales for mediation, reaction to literature, online interaction, young learners, and sign

languages (Council of Europe, 2018). CEFR was designed as a result of the work of an

interdisciplinary team across Europe with the aims of

promoting and facilitating co-operation among educational institutions in different countries;

providing a sound basis for the mutual recognition of language qualifications; assisting learners,

teachers, course designers, examining bodies and educational administrators to situate and co-

ordinate their efforts; facilitating quality in language education and promoting a Europe of open-

minded plurilingual citizens (Council of Europe, 2018, p. 25-26).

The CEFR breaks with Chomsky’s traditional distinction between competence and

performance and instead focuses on proficiency by proposing a ‘descriptive scheme of

language proficiency’, which, in this model, comprises the ability to perform

communicative language activities drawing on general competences or savoirs (e.g.

knowledge of the world), and communicative language competences (linguistic,

sociolinguistic and pragmatic), while making use of appropriate communicative strategies

(reception, production, interaction, mediation). As a proficiency model of CC, the CEFR

“embraces a view of competence as only existing when enacted in language use” (Council of

Europe, 2018, p. 33). Evoking Bachman and Palmer’s underlying view of communication,

the CEFR equates communication with language use and adopts an action-oriented

approach that “put[s] the co-construction of meaning (through interaction) at the centre of

the learning and teaching process” (Council of Europe, 2018, p. 27).

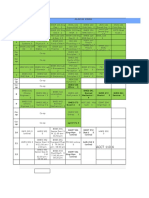

Figure 1. Components of the Descriptive Scheme of Language Proficiency (Council of

Europe, 2018, p. 30).

Unlike previous models of communicative competence that highlighted language skills

(listening, speaking, reading and writing) as core outcomes around which to design

communicative activities, the CEFR privileges communicative language activities and

strategies of reception (e.g. identifying cues and inferring), production (e.g. spoken and

written messages produced through strategies such as planning, compensating and

monitoring and repairing co-constructed language), interaction (e.g. spoken, written and

online interactional activities that are supported by interaction strategies such as turn

taking, cooperating, and asking for clarification), and mediation, which seem to more aptly

reflect how people use language. This latter - mediation - marks a clear shift from previous

models of CC in that:

In mediation, the user/learner acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or

convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes from one language to another

(cross-linguistic mediation). The focus is on the role of language in processes like creating the space

and conditions for communicating and/or learning, collaborating to construct new meaning,

encouraging others to construct or understand new meaning, and passing on new information in an

appropriate form. The context can be social, pedagogic, cultural, linguistic or professional (Council of

Europe, 2018, p. 103).

By introducing the concept of mediation, the CEFR situates its proposal within a

constructivist paradigm where language users-as-mediators adopt a central role in co-

designing and negotiating meanings through the construction of a pluricultural shared

space where linguistically and culturally diverse interlocutors are expected to engage in

positive and successful intercultural exchanges. In this way, the CEFR presents a more

comprehensive discussion of the intercultural dimension, scarcely found in Canale (1983),

Bachman and Palmer (1996) or Celce-Murcia et al.’s (1995) models. While the CEFR locates

the intercultural dimension within sociolinguistic or pragmatic competence, the former

models, to a great extent in consonance with Byram (1997), describe the intercultural

dimension as a separate component, yet still in close conjunction with pragmatic and

sociolinguistic competences. Nonetheless, in the CEFR, intercultural (pluricultural)

capabilities appear as communicative language activities and strategies rather than as a

full-fledged competence as presented in other models of intercultural competence (see also

Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009).

What is noticeable about the ‘descriptive scheme of language proficiency’ is that the idea of

reaching CC is substituted by the idea of reaching language proficiency. The traditional

components of CC are subsumed under a broader umbrella and the component of strategic

competence common to all previous models is conceptualized as communicative language

strategies that include planning, execution, and evaluation and repair, all of which operate

in different modes of communication: production, reception, interaction, and mediation. By

doing this, the CEFR evokes Celce-Murcia at al’s (1995) decision of locating the strategic

competence as surrounding the other components of CC to foreground the ubiquity of

strategic activities, thereby marking a step forward in showing the interrelatedness of the

components of CC.

However, a critical look at the CEFR’s model of language proficiency leads one to conclude

that it is unable to transcend the verbocentric perspective characteristic of its predecessor

models. In this model, language precedes communication as can be observed in the

‘descriptive scheme of language proficiency’ (see Figure 1) where ‘Overall Language

Proficiency’ appears as a superordinate term within which the components of CC appear as

subordinated. Moreover as shown above, communication is equated with language use, a

purview that is not completely aligned with the constructivist and ecological principles to

which the CEFR claims to adhere: “CEFR scheme is highly compatible with several recent

approaches to second language learning, including the task-based approach, the ecological

approach and in general all approaches informed by sociocultural and socio-constructivist

theories” (Council of Europe, 2018, pp. 29-30). In particular, we find limited

correspondence with ecological perspectives where language constitutes a semiotic system

among other systems that constitute communication. In this regard, van Lier (2004) states:

Language is not a system of communication that occurs in a vacuum. On the contrary, it is an integral

part of many connected meaning-making systems, in other words, it’s part of semiotics. In Chapter 2 I

presented a diagram of concentric circles that shows how important gestures, intonation, social and

cultural knowledge of various kinds, and so on, are. Meaning-making processes draw on all

those systems and clues, in interpretive processes of complex kinds (p. 223).

Although the CEFR acknowledges that paralinguistic elements participate in

communicative exchanges and includes descriptors for paralinguistic strategies, it does not

stray from the discourse that these elements are subservient to the language realm. As a

result, it dismisses the fact that paralinguistic elements (e.g. gesture, gaze) are part of a

semiotic system that informs communication as a whole. Yet, all types of communication

are multimodal in some way (Kress, 2010; Álvarez Valencia, 2016a; 2018). van Lier (2004)

asserts that “[c]ommunication is in reality always multimodal, that is, it involves more than

just seen or heard language. It also involves artifacts, pictures, gestures, movement and

much else” (p. 184). The CEFR, however, does not necessarily coincide with this postulate,

noting that: “Online interaction is dealt with separately because it is multimodal” (Council

of Europe, 2018, p. 93).

In sum, the CEFR, as well the models described in this section, represent a valuable

contribution to the understanding of the concepts of CC and communication in language

learning and teaching. Along its path, the field of applied linguistics and in particular

language teaching and learning have benefitted from contributions from different

disciplinary areas (Stern, 1983) that have enriched applied linguistics’ understanding

regarding the why, the what, and the how of its object of inquiry.

Different comprehensions of language (Graddol, 1993; Richards & Rodgers, 2001; van Lier,

2004; Kumaravadivelu, 2006; Larsen-Freeman, 2011; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013; Álvarez

Valencia, 2016b) and communication (Eisenchlas, 2009), along with their relationship with

one another, continue to emerge. Synthetic, logical, quantifiable, descriptivist and

categorical discursive constructions common in quantitative and positivist views of

knowledge inform most of the models of CC discussed above. In most cases their creation

has been motivated by assessment and testing agendas, which explains why subjective

dimensions such as power dynamics that partake in communication are absent from these

models, and instead communication has been reduced to an objective, transactional,

measurable activity. Kramsch (2016), for example, calls attention to this omission and

indicates that all human communication is a site of struggle where power is constantly

framed and re-framed. She proposes symbolic competence as “the ability to judge when to

speak and when to remain silent, when to talk about the inequalities of the ongoing talk

and when to let them pass, when to complain or counter-attack, and when to gently but

unmistakably read just the balance of power through humor or irony” (2016, p. 526). In

other words, symbolic competence implies a capability to identify how communicative

practices index discursive constructions about identity, race, gender, politics, and economic

interests.

The question about what it is that language teachers ought to teach–language (i.e. one of

many semiotic codes), or communication (i.e. meaning-making through all semiotic

modes), or discourse (i.e. culture and communication in mutually constitutive relationship

with one another)--is still unresolved given the verbocentric centrifugal forces of the

academic tradition that have governed applied linguistics. Although the language teaching

field has made enormous strides in studying language as communication (as exemplified by

the models of CC discussed above), it has failed to realize that language is not the only

component of communication, but one among many other semiotic systems that comprise

communication and constitute a discourse system. Furthermore, by presenting face-to-face

interaction as the main source of CC, it has also failed to acknowledge that in pedagogical

practice students’ interactions with other types of texts constitute a major resource for

communicative and (inter)cultural growth. The discussion around the development of CC

has become more complex with the recent emphasis on the cultural dimension, engendered

by recent developments in the social sciences and the transition from what some scholars

have called the ‘cultural turn’ (Byrnes, 2002; Byram, Holmes, & Savvides, 2013) towards

the ‘intercultural turn’ (Borghetti, 2013). We now turn to discussion of models of IC that

have been recruited in service of measuring yet another competence, and demonstrate their

rigid attachments to their CC predecessors.

INTERCULTURAL MODELS IN SECOND/FOREIGN LANGUAGE EDUCATION

Except for the model of language proficiency proposed by the CEFR, in previous models of

CC the role of the intercultural dimension was marginal. Although they acknowledged the

relevance of cultural or cross-cultural aspects in S/FLE, their understanding aligned more

with a culturalist view (Bayart, 2005; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013; Dervin, 2010); that is, the

precept that cultural groups are homogeneous, stereotypical, and groupings are logical and

static. The intercultural perspective had long developed in other disciplines including

communication, social and cross-cultural psychology, anthropology, international business,

cultural studies, sociology (Balwin, 2017; Jackson, 2014), before gaining relevance in the

area of S/FLE through the work of scholars such as Geneviève Zarate, Michael Byram,

Claire Kramsch, John Corbett, Manuela Guilherme, Anthony Liddicoat and Angela Scarino,

to name only a few.

In higher education in general, and in S/FLE in particular, the most commonly

used and referenced IC models are those developed by Bennett (1986), Fantini (2009),

Byram (1997), and Deardorff (2006). Bennett's (1993) Developmental Model of

Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) is a linear model that describes individuals transitioning

from an ethnocentric to an ethnorelative state after experiencing six stages: Denial,

Defense, Minimization, Acceptance, Cognitive Adaptation, and Behavioral Adaptation.

Accordingly, in the first three stages the individual is not able to see outside his/her own

perspective while in the latter the individual develops the ability to think pluralistically.

The assumption is that individuals progress along a continuum toward a state of

ethnorelativity, which can be facilitated by encounters with people from other cultures. A

fundamental view inherent in this model is the framing of IC development (which it in fact

terms ‘intercultural sensitivity’) in the context of an individual’s reaction to a cultural

context (rejection of another cultural context and/or people through denial or defense

versus acceptance through acculturation or adaptation). Development is thus presumed to

occur in a linear process as a result of intercultural contact: specifically, where a sojourner

leaves his or her home country, travels to another country (and cultural context) and must

negotiate his or her affective feelings and reactions to a variety of cultural and social

situations.

Fantini (2009)’s comprehensive model comprises a series of attributes, abilities,

dimensions, and target language proficiency and developmental levels. With regard to

attributes, Fantini (2009) poses that an interculturally competent speaker is characterized

by qualities such as “flexibility, humor, patience, openness, interest, curiosity, empathy,

tolerance for ambiguity, and suspending judgments” (p. 459). In turn, these attributes

contribute to communicative efficiency achieved through three abilities: ability to establish

and maintain relationships, to avoid distortion or communication breakdown, and to

cooperate to accomplish a task with an interlocutor. The author then introduces four

dimensions that are common to other IC models: knowledge, attitudes, skills and

awareness, where awareness takes central stage as the propeller for development of other

dimensions. Like others, Fantini’s model incorporates a developmental component,

however distinguishes itself from Bennett’s (1986) developmental model by

acknowledging that IC is longitudinal and undergoes periods of progression, regression, or

stagnation. Fantini (2009) asserts that “target language proficiency is frequently ignored in

many models of intercultural competence” (Fantini, 2009, p. 459), which he deems vital, in

that the level of proficiency in the target language constrains or enhances, qualitatively and

quantitatively, the attainment of intercultural competence. However, here the language

dimension is reduced to knowledge of the host country language, thereby assuming that IC

is developed in the context of international travel.

Byram’s (1997) model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) is grounded in a

view of culture as “meanings, beliefs, and behaviours” (34), and an interactionist view of

communication where every encounter involves meaning negotiation. Unlike other models

of IC, Byram’s model integrates three traditional components of CC proposed in previous

frameworks: linguistic, sociolinguistic, and discourse competence. Likewise, like most

frameworks of IC (Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009), Byram’s model also contains cognitive,

affective, and behavioral domains, calling these: knowledge (or savoirs), attitudes of

openness and curiosity (savoir être), and skills. The latter domain is subdivided into three

areas: skills of interpreting and relating (savoir comprendre), skills of discovery and

interaction (savoir apprendre/faire), and critical cultural awareness/political education

(savoir s’engager) (pp. 89-102). More recently, Byram (2008) has expanded the component

of savoir s’engager linking it to the promotion of intercultural citizenship. The popularity of

Byram’s model in educational contexts can be attributed to the fact that not only does it

introduce a general descriptor for each IC dimension, facilitating assessment, but also a set

of curricular objectives that further qualifies each general descriptor. Byram’s (1997)

model developed out of the context of the Council of Europe around the time that

discussions about plurilingualism and interculturality were central to the European project

of charting S/FL learners’ language development through the CEFR. The imagined audience

for this model was, at the time, sojourning European students traveling to other countries

for exchange or study abroad. The interculturally competent individual in Byram’s original

model was an intercultural speaker (Byram, 1997, p. 72), which was a countermove to the

notion of native speaker in S/FLE (Wilkinson, 2012), a decidedly unattainable goal, and

therefore emphasized instead the flexibility of S/FL students in intercultural encounters,

specifically, encounters resulting from international mobility between nations. Although it

was not proposed with a specific accompanying assessment instrument, the model has

served as point of departure for others, such as the Intercultural Competence Assessment

(INCA) (European Commission, 2004) project which proposes levels of IC and assessment

rubrics describing a participant’s skill level.

Deardorff’s (2006) Pyramid Model of IC, although less frequently used in applied linguistics

research, is widely cited within the professional field of study abroad (in the US context),

particularly for the way in which her work offers a concrete model for educational

institutions to begin developing a comprehensive assessment system. IC in this context is

seen as a general project of US higher education, unlike Byram’s model where IC

development is linked to S/FL education. Like Bennett (1986) and Byram (1997),

Deardorff’s model incorporates cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. The

process begins within the individual and some ‘Requisite Attitudes’ that imply

predisposition of favorable attitudes such as respect, openness and curiosity. The

individual moves in a circular, recursive process from having these favorable pre-

dispositions, to developing specific ‘Knowledge and Comprehension’ and ‘Skills’ (e.g. listen,

observe, interpret), to the next phase which involves a shift in the internal frameworks

(‘Desired Internal Outcomes’), followed finally by an external outcome, i.e. the way in which

an individual behaves (‘Desired external Outcomes’ ). This process then feeds back into

the attitudes held by an individual and allows the cycle to repeat. In Deardorff’s model, the

“Knowledge & Comprehension” outcome includes “Cultural self-awareness, deep cultural

knowledge, and sociolinguistic awareness” (Deardorff, 2006, p. 256), thus we see a specific

reference to the importance of language, however, this is not a salient characteristic of the

model.

A critical appraisal of these four IC/ICC models highlights their limitations in their

respective views of communication. Although Byram’s and Fantini’s models highlight the

role of language and communication in developing IC, they are fraught with some of the

same limitations that characterize models of CC. First and foremost, they adopted a concept

of competence traditionally associated with the cognitive realm, thereby locating CC or IC

in the individual, and fragmenting competence into different components. The models

discussed here, and in general most models of IC, are list-oriented models (Matsuo, 2012;

Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009) because they prescribe cognitive (knowledge), emotional

(attitudes), and behavioral (skills) components upon which an individual should be

assessed. By focusing on the individual and locating IC in the mind, these models ignore the

notion that in communicative acts, competence is not located uniquely inside an

interlocutor, and are unable to theorize the interlocutor, the relational and interactional

aspects of communication, interdependencies, combinations, and levels of development

(Matsuo, 2012; Dervin, 2010). In terms of pedagogical practice, Matsuo (2012) asserts that

list-oriented models do not assist teachers properly because although they permit teachers

to identify when elements of the competence are present or absent in individual students,

it is difficult for teachers to operationalize them in terms of establishing relations and

dependencies among the competencies, let alone aligning pedagogical practice with these

outcomes. In their urge to comply with institutional and market demands rooted in

positivist assessment logics, proper of Eurocentric epistemological views (Peña Dix, in

press; Dervin, 2010; Lynch, 2001; Borghetti, 2017), commercial assessment models of CC

and IC (e.g., Hofstede, 2012; Hammer, 2012) have become desirable objects that, in the end,

support the one-size-fits-all ideology underlying pedagogical material design and

approaches in S/FL teaching. As a result, narrow, monolithic and static views of culture and

communication are imposed.

With the exception of Byram’s (1997) model which does include nonverbal elements of

communication and also acknowledges that discovery and interaction with ‘documents’ are

also sources of IC development, the models emphasize face-to-face encounters as the main

source of competency development, downplaying the role of engagement with other types

of texts as relevant sources for promoting interculturality. The models’ historical

conceptions of IC as anchored in interactional encounters between members of

transnational groups have given rise to a preponderance of empirical studies where IC is

didacticized primarily through such pedagogical formats and spaces as study abroad (e.g.

Shiri, 2015; Shively, 2010), telecollaboration (e.g. Ware, 2005; 2013), classroom role plays,

international guest speakers (e.g. Liu, 2017), and so forth. Many such activities involve

either physical or virtual mobility and therefore contact with speakers of the target

language or “cultural informants” from countries associated with the target language (see

also Piątkowska & Strugielska, 2017; Sercu, 2004). These formats and activities suggest a

view of IC as emerging only in people-to-people contact spaces, and place the pedagogical

focus on analysis of and/or reflection on interactions, miscommunications, or differences in

pragmatics. Such projects also tend to focus on the learner-as-speaker, and the

communicative patterns he or she adopts and deploys in moments of interaction. Put

another way, attention is focused on the productive mode of communication, and the

visible behaviors of learners that can be measured against the backdrop of the prescribed

ingredients that are theorized as evidence of IC.

Thus models of IC seem to serve as a signpost for what being intercultural looks like, but do

not adequately address, nor guide, in processes of becoming intercultural. By outlining the

ingredients of an interculturally competent individual, they serve to facilitate educational,

and indeed commercial, projects of assessment, yet leave behind any substantial

articulation of how exactly learners can get there. Although we acknowledge the relevance

of historical and contemporary models of CC and IC and the role they have played in

extending the horizons of applied linguistics, we argue that in S/FLE we should depart

from practice to design dynamic models, and not from models to design practice.

REFRAMING GOALS FOR SECOND/FOREIGN LANGUAGE EDUCATION

Indeed, foreign language education is particularly synergistic with fostering interculturality

if one takes the perspective that becoming intercultural requires knowing how to read both

micro-level signs (i.e. in the interactional moment where meanings are being expressed)

and macro-level signs (i.e. the kind of social positioning occurring, and the broader socio-

cultural context). By “reading” we are referring to processes of “reading” individuals in

face-to-face communication situations, as well as processes of reading texts. In the

remainder of this chapter we argue that developing students’ interpretative capacities

through encounters with texts can be a precursor to more successful1 face-to-face

encounters with others, as the interpretive strategies and stances students can learn to

adopt in processes of textual interpretation can be, theoretically, applied to processes of

“reading” people. As Kern (2000) has asserted, “cultural understanding does not

automatically result from communication contact alone, but depends on a negotiation of

difference in genres, interaction styles, local institutional cultures, and culture more

broadly” (p. 276).

Following many others (e.g. Kramsch, 2011, 2016; Holliday, Hyde & Kullman, 2010;

Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013; Scollon, Scollon & Jones, 2012), we conceptualize culture as

dynamic and discursively constructed. Cultures, or rather discourse communities (Kramsch,

1995), emerge based on affinities (e.g. shared work, ethnic origins, hobbies, etc.), where

affiliations are fluid, and patterns of interaction—including social practices and

communication—are simultaneously conventional and variable. Individuals choose

particular forms of verbal and non-verbal communication (e.g. language, forms of

discourse, politeness strategies, clothing, gestures, body language, etc.) based on a

combination of their available semiotic resources, their understanding of conventions, their

choice to conform or not with those conventions, the particular identities they wish to

express, and/or the ideological stance they adopt. Thus, understanding culture requires

understanding discourse systems (Scollon, Scollon & Jones, 2012; Swaffar, Arens, and

Byrnes, 1991). An interculturally competent individual must have a certain degree of

discourse community-specific knowledge and a general intercultural stance that is open to

listening exquisitely in the communication moment for clues into how and why a speaker,

or text-author, is expressing him/herself in a particular way.

We propose that encounters with discourse communities via the interpretation of material

texts that not only incorporate the linguistic dimension but also other semiotic resources

that partake in meaning making processes can serve as a pre-text for successful encounters

with others. In so doing, we draw upon a multimodal social semiotic approach (Kress,

2010), including the notions of design and multimodality, and Pedagogies of Multiliteracies

(New London Group, 1996; Cope and Kalantzis, 2009), including the notion of genre in

order to demonstrate the compatibility of these principles in helping learners to prepare

for, participate in, and analyze intercultural encounters. Indeed, much scholarship has

argued for integrating activities of curating and/or analyzing cultural texts and discourses

in S/FLE contexts in the interest of developing IC, for example: portfolios exploring

stereotypes (Allen, 2004), analyzing ads (Moeller & Faltin Osborn, 2014) or film and other

media (Xue & Pan, 2012; Etienne & Vanbaelen, 2006, 2017; Daniel, 2017). While not all

studies necessarily refer to the development of IC, per se, such pedagogical projects align

with our view of intercultural experiences as occurring not only in the spaces of encounter

of individuals with members of other discourse communities, but also with texts of those

communities.

Intercultural communication as the encounter of designs of meaning

Each act of textual creation and interpretation involves processes of designing meanings. In

invoking the concept of design, we draw upon Kress (2000a; 2010; with van Leeuwen,

2001) where ‘designing’ is sign-making. Following a social semiotic perspective, ‘design’ is

both representation (i.e. the selection of material resources needed in designing) and

communication (i.e. the consideration of one’s interlocutors, communication context, what

is socially appropriate, or transgressive.) ‘Design’, therefore, simultaneously incorporates

both structure and human processes of transforming social structures in creating a new

sign (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000). ‘Design’ is inherently dynamic: it implies that sign-makers

are constantly making choices in the moment of production of a message. This nuanced

view of ‘design’ underlies Kress’ (2010) multimodal social semiotic model of

communication, wherein a ‘rhetor’ is an agentive sign-maker who creates a sign in

response to a ‘prompt’ in the world. The rhetor, also often one in the same individual as the

‘designer’, selects the most apt resources for meaning making based on the particular

context in which s/he is acting (i.e. relationship with the interlocutor or institution, etc.).

The model accounts for an ‘interpreter’ who then takes this message (called the ‘ground’)

as a ‘prompt’ for meaning making in an ongoing chain of semiosis (Kress, 2010, p. 53). Acts

of meaning within this model occur out of the ‘interest’ of the sign maker; that is to say, the

rhetor has a particular goal or purpose: to communicate an idea, or an identity, or promote

a particular institutional discourse (e.g. Michelson & Álvarez Valencia, 2016). What is more,

the rhetor/designer is not merely choosing an available sign and re-using it, but rather is

re-making a new sign from available resources, based on what s/he considers to be the

most suitable semiotic resources for expression of his or her meanings.

As understood in Kress’ (2010) conceptualization of communication and ‘design’, identity

is not a static construct that is fixed prior to a particular moment of interaction or textual

production, but rather identity is constructed in the very act of such productions. As such,

this particular social semiotic conception of communication aligns with contemporary

notions of intercultural communication that view all interactions as negotiated

interactions. Put another way, we do not have identities or cultures, we perform them

(Holliday, Hyde & Kullman, 2010; Piller, 2000, cited in Dervin & Liddicoat, 2013) and those

performances are dependent on the dynamic nature of the communication context. The

notion of ‘design’ is further compatible with dynamic conceptions of intercultural

communication because it foregrounds the fact that the manner in which an individual

expresses meanings is partially related to the extent of their available design resources.

Furthermore, the available designs from which learners, teachers, or designers choose apt

resources for meaning making are culturally shaped. Different cultures have different

modal priorities, i.e. modes that are preferred over others as the most apt modes for

representation and communication of meaning (Kress, 2000, p. 199) not to mention

different linguistic available resources between individuals who share the same language.

Individuals’ selection of apt resources is thus shaped by what they have available to them

through their socialization, history, current context; in other words, what they have

gathered as meaning making resources throughout their lives (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000).

The extraordinary range of resources available to individuals for designing are “never

simply of one culture but of the many cultures in their lived experience; the many layers of

their identity and the many dimensions of their being” (ibid., p. 204). Reiterating a central

theme in Kress’ work, Cope and Kalantzis (2000) also assert that designing does not merely

involve reproducing; rather designing is about creating (ibid.). Kress (2003) refers to this

process of designing as “doing semiotic work” (p. 37) in that by using signs, designers

simultaneously transform the environment in which the work is done, and are themselves,

also transformed in the process (Kress, 2000a, p. 155).

From pedagogical practice to dynamic models

Reframing the central goal of S/FLE from one of developing CC, and by extension

intercultural CC, to one of expansion of learners’ semiotic resources opens up substantial

new possibilities for teaching for interculturality. We now turn to a review of three

pedagogical projects from our own and others’ work in both L1 and L2 environments

which illuminate the ways in which broader views of communication--as multimodal, as

encounters with texts, as dynamic and socially co-constructed--have found relevance

within classroom contexts. Together, these pedagogies suggest a set of ingredients for

teaching for interculturality in shifting the focus from one of being interculturally

competent to one of becoming an effective intercultural interpreter and meaning designer

through attention to another rhetor’s designs of meaning and to one’s own meaning

designs that ensue from interactions with texts.

Designing meaning through multimodal genres

Ryshina-Pankova (2013) outlines the design of an advanced course in German centered

around discourses of environmentalism in Germany, using a range of genres through which

to expose students to both historical and contemporary discourses around this topic. By

virtue of incorporating multiple textual genres, students are invited into this topic and its

attendant discourses through multiple access points. Genre-based pedagogies are

especially compelling in engaging learners in inquiry of authentic texts of S/FL discourse

communities through analysis of how lexicogrammatical choice, author, audience, purpose

interconnect within a particular genre through the development of close reading of texts.

Furthermore, genre, through its role in “coordinat(ing) resources, … specify(ing) just how a

given culture organizes this meaning potential into recurrent configurations of meaning,

and phas(ing) meaning through stages” (Martin, 2009, p. 12) offers important pedagogical

scaffolds for the individual learner and the level of within-course instruction through its

predictable structures (Swaffar, 2004; Byrnes, 2005; Maxim, 2006), and its “web of text-

based performances that mobilize(s) audiences’ expectations in particular ways” (Arens,

2008, p. 39). Finally, as Byrnes, (2006) asserts: “careful meta-awareness of language use in

context not only encourages interpretive depth in and of itself; it also provides a

sophisticated, language-based, and transparent entree into an understanding of culture….”

(p. 43). Not only does Ryshina-Pankova incorporate multiple genres, she is intentional

about incorporating a range of multimodal genres. Multiple modes are important because,

as Kress (2003) asserts, different modes organize knowledge in different ways; each brings

its own distinct epistemological commitments (p. 57). As Kress describes: “The question

asked by speech, and by writing, is: ‘what were the salient events and in what (temporal)

order did they occur?’… while the question asked by display is: ‘what were the salient

entities in the visually encountered and recollected world, and in what order are they

related?’” (p. 14). Thus expansion of modes beyond a linguistic, verbocentric-only mode

typically prioritized in S/FL classrooms substantially expands possibilities for

understanding communication, and by extension intercultural communication. In addition

to the incorporation of multiple multimodal genres, a further strength of Ryshina-

Pankova’s (2013) project lies in the enumeration of specific guiding questions that serve as

a framework for helping learners unpack meanings in multimodal texts, all while drawing

upon their developing knowledge of discourses of environmentalism gleaned through

various texts.

Designing meaning through inner multi-modal sign-making

Taylor (2014) reports on a pedagogical project in which 13- and 14-year old students read

four different texts in their first language (two literary and two non-literary) and were

interviewed about their ‘inner sign-making’ in responses to those texts either through

visual sketches or through spoken or written signs (p. 230). Students’ responses were

categorized as either visual images, sounds, feelings, sensations, inner speech, or

reminders, categories that had emerged out their responses to texts in a previous phase of

the study. Visual images were the most common type of sign created by the students, which

the researcher analyzed through Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2006) Grammar of Visual

Design framework. Specifically, among the group of five students’ responses were various

physical positions that they imagined for themselves vis à vis characters in one of the texts,

some imagining themselves on a similar plane, and others on a mountain top looking down

at the characters. Further responses evidenced students’ visualizations of the texts in either

film-like or series of still images, as well as students’ awareness of their voicing of the text

at various moments. Finally, all students shared experiences of sensations and feelings

experienced in the reading process, which varied from student to student. One could

imagine an extension of this project in which students are privy to each others’ inner multi-

modal signs as responses to texts. By sharing responses among the class, students become

sensitive to the variable reading positions taken up by individuals, which Swaffar and

Arens (2005) tacitly suggest is a precursor to becoming interculturally ‘competent’: “For

learners to behave as adults in cultural contexts, they must learn to negotiate cultural

differences, not expect absolute consensus, for example, about the meaning of a … text” (p.

95). Furthermore, allowing students to render their responses to texts through more than

mere verbal responses affords an expansion of possibilities for readers to design meanings

as they interact with texts.

Re-designing meaning through the voice of an other

Michelson and Petit (2017), drawing on Michelson and Dupuy (2014), present a model for

guiding students in encounters with multimodal texts, where students designed meanings

not as themselves, but through the lenses of fictitious characters whose identities the

students developed within the context of a Global Simulation2 framework. Interactions

between students-as-characters took place within the context of an imagined apartment

building in contemporary Paris, and in response to various situations and events the

characters encountered in their personal and professional lives. Situations, though

fictionalized, emerged out of actual events (e.g. mayoral elections in Paris, a controversial

immigration case), whose discourses students came to know through encounters with

texts. For example, in the case of the controversial arrest of Leonarda, an undocumented

high-schooler from Kosovo, students engaged with texts that summarized the events and

also presented various responses to those events. Specifically, they read an online news

article, in which were embedded: an image of Leonarda, an audio clip featuring groups of

highschoolers protesting in the streets, and a video clip of President Hollande’s public

address justifying the arrest. Students were guided in processes of interpretation and

analysis of texts by reflecting on visual designs in the image (i.e., colors, layout, posture),

their inter-relationship with the linguistic designs of the caption, and the relationship of

this ensemble of designs to the topic of immigration and the implied emotions of the young

girl. Further, they reflected on language forms (registers, colloquial expressions,

passive/active constructions) used by various rhetors, and the way in which these carried

particular messages. Authors present a sample set of guiding questions inviting students to

reflect on these different genres, as well as excerpts from students-as-characters’

responses to these events (e.g. social media posts, phone conversations with neighbors,

personal journal entries about the events). Authors demonstrate the way some students

were able to take up forms of discourse that reflected both their characters’ identities and

the ways in which French people were talking about and reacting to the events; in other

words, these students-as-characters became part of the conversations of the

foreign/second language discourse world, even if only virtually in the context of the

simulation. Additionally, students reflected on their design choices, in some cases

becoming aware of how the vehicle of the character invited them to think into and from

within a perspective outside of their default first language/cultural frame, as noted by one

student: “I believe that my character . . . was very different from myself and my general

opinions but by creating a character that contradicts your values or opinions you are

challenged to find the background knowledge to support these views” (Michelson & Petit,

2017, p. 154).

Taken together, these sample projects offer a heuristic for interpreting visual images,

demonstrate how entry into S/FL discourse worlds can be brought about through

encounters with multiple genres, offer expanded design possibilities for readers to express

their thoughts and feelings related to texts, call to attention learners’ own reflections on

their reading processes through their voicing of their responses, and offer concrete

examples of what can occur when learners are invited to redesign meanings through the

voice of an other in their own textual productions. Although not always explicitly stated in

these projects, such pedagogies align well with broader views of communication and

intercultural communication and multiliteracies approaches to teaching (New London

Group, 1996; Cope & Kalantzis, 2009), through their attention to the multi-modal nature of

semiotic resources for meaning-making, multiple ways in which meanings can be made

through the choice of available semiotic designs, and the acknowledgement of the

multitude of different backgrounds and social histories brought to the communication

situation.

We depart from these pedagogical models to formulate the following general principles for

S/FL education within a general project that reframes the concept of communication and

intercultural competence to focus on students’ process of becoming effective intercultural

interpreters and meaning designers.

1) Because different genres recruit semiotic forms differently and organize them according

to expected conventions of particular discourse communities, instruction should

incorporate multiple textual genres, with guided analysis of the relationship between

material semiotic resources and social, cultural or ideological meanings.

2) Because different modes communicate knowledge differently, instruction should

incorporate opportunities for interpretation of, as well as design of multimodal texts.

3) Similarly, learners should be invited to respond to texts not only through language, but

through other modes that might allow them to most aptly represent their interpretations.

4) Because our textual responses arise from encounters between our subjectivities and the

text, guidance in and dialogue around texts should be de rigeur.

5) Learners should be provided with opportunities for perspective-shift in order to raise

conscious awareness of values being conveyed and the semiotic resources being used to

convey those values.

6) Active, conscious, and articulated reflection on meaning designs, in both interpretive and

productive communication modes should accompany all encounters with texts.

In our view, adopting and incorporating these principles into the design of S/FL classroom

practice more completely acknowledges communication as occurring within different

design modes, within particular, situated, social contexts, and as a dynamic process of

choosing designs that most aptly fit a communication situation. Indeed, the models

presented here represent only a few of the growing number of projects that demonstrate

the way that S/FL classroom practice is already teaching for interculturality, which we

propose can be understood as:

an ability to move beyond the default mode of merely applying one's own available designs to a

communication situation, through development of the knowledge of other possible available designs

and a sensitiveness to understanding how such designs might be being recruited in order to make

meaning.

Intercultural communication is, ultimately, about encounters with others--whether in face-

to-face interactions, online interactions, or mediated through textual productions. In any

initial encounter, it is natural to “read” others against the backdrop of existing stereotypes

about particular communities or groups with which we associate our interlocutors or the

texts before us. In the S/FL classroom where language and culture are mediated largely by

texts, we have a particular opportunity to foster skills of learning to read others against the

backdrop of new discourse worlds, by guiding students in detailed analyses of textual

designs, introspection on their own responses to those designs, and by calling to conscious

awareness the subjective positions we take up in the interpretation of others’ designs. In

learning to “read” texts, we can learn to interpret semiotic design choices (e.g. language,

image, sound, intonation, gesture, etc.) based on a text’s context of production, including

author interest, assumed or intended audience, etc. Such textual interpretive skills might

also then mirror a general disposition of learning to read others not against stereotypical

backdrops, but rather against the backdrop of the identities and interests we ‘read’ them to

be performing and expressing in that moment.

However, such dynamic design processes elude facile measurement. Indeed, frameworks

such as the New London Group’s (1996) Pedagogy of Multiliteracies, Cope & Kalantzis’

(2009) Learning by Design, and Kramsch’s (2006; 2011) conception of symbolic competence

present excellent points of departure for teaching designing meanings in both interpretive

and productive domains. And, while countless research and pedagogical projects in first

and second language education have taken up these orientations to learning, literacies

pedagogies remain in the margins of S/FL educational practice. Yet, literacies pedagogies

are directly tied to interculturality if one considers that becoming intercultural involves

becoming sensitive to both conventions and breaks with convention of particular forms of

discourse recruited for communication across a broad range of cultural texts and contexts,

and becoming sensitive to the variable ways in which rhetors recruit different signs and

symbols in order to convey messages based on a combination of their available design

resources, their understanding of conventions, their choice to conform or not with those

conventions, the particular identities they wish to express, and the ideological stance they

adopt.

CONCLUSION

As elaborated throughout this chapter, the rootedness of S/FLE in narrow notions of

communication and a pre-occupation with ‘competence’ in models of communicative and

intercultural competence places emphasis--both theoretically and practically--on

measuring and assessing learner outcomes, and has greatly constrained possibilities for

implementation of more dynamic frameworks into mainstream pedagogical practice. This

preoccupation construes the object of learning in S/FLE as one of acquiring a linguistic

code to a degree of proficiency that affords ‘appropriate’ interactions with interlocutors

rather than one whose central aim could be seen as expanding semiotic resources for

meaning-making, resources that would then theoretically be available in all forms of

intercultural communication: not only the interactional encounter between members of

transnational groups, but also at the intranational and intragroup level, where different

sociocultural practices and choices about the presentation of self that crystalize

individuals' identities and affiliations are inherent in every encounter. Waugh, Álvarez

Valencia, Do, Michelson & Thomas (2013) reminded us that “[l]inguistics has moved from a

monologic view of the language faculty towards a more dialogical, pluralistic, dynamic and

integrative view of how speakers, contexts and meaning interplay” (p. 634). Paradoxically,

mainstream S/FL language education continues to lag behind, though not for a dearth of

materials. If education purports to prepare students for experiences in the world, then it is

the responsibility of S/FL education to embrace a view of communication that more aptly

reflects how meanings are made and exchanged in all manner of encounters.

References

Allen, L. Q. (2004). Implementing a culture portfolio project within a constructivist

paradigm. Foreign Language Annals, 37(2), 232–239.

Álvarez Valencia, J.A. (2016a). Meaning making and communication in the multimodal age:

Ideas for language teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(1), 98-115.

Álvarez Valencia, J. A. (2016b) Language views on social networking sites for language

learning: the case of Busuu, Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29:5, 853-867, DOI:

10.1080/09588221.2015.1069361

Álvarez Valencia, J.A. (2018). Visiones de lengua y enseñanza de lengua extranjera: una

perspectiva desde la multimodalidad. In M. Machado (Ed.), Reflexões, perspectivas e

práticas no estágio supervisionado em letras (pp. 56-72). Cáceres, MG: Editora Unemat.

Arens, K. (2008). Genres and the standards: Teaching the 5 C's through texts. The German

Quarterly, 81(1), 35–48.

Bachman, L. (1990) Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford University

Press

Bachman, L. F. & Palmer A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Baldwin, B. (2017). Murky waters: Histories of intercultural communication. In I. Chen

(Eds.), Research in intercultural communication (pp. 19-43). Boston, MA: Walter de

Gruyter.

Bayart, J. F. (2005) The illusion of cultural identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(2), 179-196.

Berns, M. (1990). Contexts of competence social and cultural considerations in

communicative language teaching. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media,

LLC.

Block, D. (2014). Moving beyond “lingualism”: Multilingual embodiment and multimodality

in SLA. In S. May (Ed), The multilingual turn (pp. 54-77). Abingdon: Routledge.

Blommaert, J., & Rampton, B. (2011). Language and superdiversity: A position paper (Paper

70) . Retrieved from Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies website:

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/innovation/groups/ldc/publications/workingpapers/70.pdf

Borghetti, C. (2013). Integrating intercultural and communicative objectives in the foreign

language class: a proposal for the integration of two models. The Language Learning

Journal, 41(3), 254-267, DOI: 10.1080/09571736.2013.836344

Borghetti, C. (2017). Is there really a need for assessing intercultural competence?: Some

ethical issues. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 44 (Jul.). Retrieved from

http://mail.immi.se/intercultural/nr44/borghetti.html

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2008). From foreign language education to education for intercultural

citizenship. Essays and reflections. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Holmes, P., & Savvides, N. (2013). Intercultural communicative competence in

foreign language education: Questions of theory, practice and research. The Language

Learning Journal, 41(3), 251-253.

Byrnes, H. (2002). The cultural turn in foreign language departments: Challenge and

opportunity. Profession, 114-129.

Byrnes, H. (2005). Literacy as a framework for advanced language acquisition. ADFL

Bulletin, 37(1), 11–15.

Byrnes, H. (2006). A semiotic perspective on culture and foreign language teaching:

Implications for collegiate materials development. In V. Galloway & B. Cothran (Eds.),

Language and culture out of bounds: Discipline-blurred perspectives on the foreign

language classroom (pp. 37–66). Boston, MA: Heinle Thomson.

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language