Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ceelie

Uploaded by

mustafasacarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ceelie

Uploaded by

mustafasacarCopyright:

Available Formats

CARING FOR THE

CRITICALLY ILL PATIENT

Effect of Intravenous Paracetamol

on Postoperative Morphine Requirements

in Neonates and Infants Undergoing

Major Noncardiac Surgery

A Randomized Controlled Trial

Ilse Ceelie, MD, PhD Importance Continuous morphine infusion as standard postoperative analgesic therapy

Saskia N. de Wildt, MD, PhD in young infants is associated with unwanted adverse effects such as respiratory depression.

Monique van Dijk, MSc, PhD Objective To determine whether intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) would

significantly (⬎30%) reduce morphine requirements in neonates and infants after ma-

Margreeth M. J. van den Berg, MD jor surgery.

Gerbrich E. van den Bosch, MD Design, Setting, and Patients Single-center, randomized, double-blind study con-

Hugo J. Duivenvoorden, PhD ducted in a level 3 pediatric intensive care unit in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Patients were

71 neonates or infants younger than 1 year undergoing major thoracic (noncardiac) or ab-

Tom G. de Leeuw, MD

dominal surgery between March 2008 and July 2010, with follow-up of 48 hours.

Ron Mathôt, PharmD, PhD Interventions All patients received a loading dose of morphine 30 minutes before

Catherijne A. J. Knibbe, PharmD, PhD the end of surgery, followed by continuous morphine or intermittent intravenous

Dick Tibboel, MD, PhD paracetamol up to 48 hours postsurgery. Infants in both study groups received mor-

phine (boluses and/or continuous infusion) as rescue medication on the guidance of

T

HE TREATMENT OF PAIN IN the validated pain assessment instruments.

young children has improved Main Outcome Measures Primary outcome was cumulative morphine dose (study

after the publications by Anand and rescue dose). Secondary outcomes were pain scores and morphine-related ad-

et al1,2 in 1987 that made clear verse effects.

that neonates have well-developed no- Results The cumulative median morphine dose in the first 48 hours postoperatively was

ciceptive pathways and therefore are ca- 121 (interquartile range, 99-264) g/kg in the paracetamol group (n=33) and 357 (in-

pable of experiencing pain. Because un- terquartile range, 220-605) g/kg in the morphine group (n=38), P⬍.001, with a between-

treated pain is both an unwanted group difference that was 66% (95% CI, 34%-109%) lower in the paracetamol group.

experience and ultimately may lead to Pain scores and adverse effects were not significantly different between groups.

adverse consequences,3-6 opioids were Conclusion and Relevance Among infants undergoing major surgery, postopera-

introduced and have been used ever tive use of intermittent intravenous paracetamol compared with continuous mor-

since.7 Opioid therapy, however, is as- phine resulted in a lower cumulative morphine dose over 48 hours.

sociated with adverse effects, in par- Trial Registration trialregister.nl Identifier: NTR1438

ticular respiratory depression.8 Re- JAMA. 2013;309(2):149-154 www.jama.com

searchers, therefore, are in search of fants. One, a randomized controlled trial cardiac thoracic or abdominal surgery,

alternative analgesic regimens in neo- of rectal paracetamol in neonates aged failed to show such an effect.10 The other,

nates and infants.9 0 to 2 months undergoing major non- however, demonstrated a fentanyl-

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) has

been proposed as an alternative. To the Author Affiliations: Intensive Care and Departments of Pharmacology, Leiden University, Leiden, the Neth-

of Pediatric Surgery (Drs Ceelie, de Wildt, van Dijk, erlands (Dr Knibbe); and Department of Clinical Phar-

best of our knowledge, only 2 studies van den Berg, van den Bosch, Knibbe, and Tibboel) macy, St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Neth-

have evaluated the opioid-sparing ef- and Anesthesiology (Dr de Leeuw), Erasmus MC– erlands (Dr Knibbe).

fect of paracetamol as add-on medica- Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, the Nether- Corresponding Author: Saskia N. de Wildt, MD, PhD,

lands; Departments of Medical Psychology and Erasmus MC–Sophia Children’s Hospital, Room

tion in postoperative neonates and in- Psychotherapy, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (Dr Duiven- Sp3458, Dr Molewaterplein 60, 3015 GJ Rotterdam,

voorden); Clinical Pharmacology Unit–Department the Netherlands (s.dewildt@erasmusmc.nl).

Hospital Pharmacy, Academic Medical Centre, Am- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient Section Editor: Derek

For editorial comment see p 183. sterdam, the Netherlands (Dr Mathôt); Leiden/ C. Angus, MD, MPH, Contributing Editor, JAMA

Amsterdam Center for Drug Research, Division (angusdc@upmc.edu).

©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 149

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

INTRAVENOUS PARACETAMOL IN NEONATES AND INFANTS

sparing effect of intravenous paracetamol operatively. When patients were ran- Assessments

in infants aged 6 to 24 months follow- domized to receive paracetamol (30 To assess pain, the patient’s nurse per-

ing ureteroneocystostomy.11 The dis- mg/kg per day in 4 doses), a placebo in- formed pain assessment every 8 hours

crepancy between these studies may be fusion of normal saline was adminis- and additionally when behavior sug-

explained by the different paracetamol tered continuously at the same rate as gested pain. Pain and distress assess-

formulations. Neither study directly an equivalent morphine infusion. When ments were performed using the

compared the analgesic effect of mor- randomized to receive morphine (pa- NRS-11 and COMFORT-B scale, re-

phine with that of paracetamol as pri- tients aged ⱕ10 days, 2.5 g/kg1.5 per spectively, which are extensively vali-

mary analgesic. It could be argued that hour; patients aged 11 days to 1 year, dated scales in neonates and infants.16-20

intravenous paracetamol with an op- 5 g/kg1.5 per hour), normal saline was When using the NRS-11, caregivers

tion for rescue morphine boluses may administered 4 times daily as placebo rate the observed pain on a scale from

further reduce postoperative opioid con- in a volume similar to the intravenous 0 to 10, where 0 represents “no pain”

sumption.12 paracetamol dose. Placebos could not and 10 represents “the worst pain pos-

We performed a randomized con- be distinguished from the active study sible,” using whole numbers (11 inte-

trolled trial in infants who had under- drug in color, odor, or viscosity. The gers including zero). The COMFORT-B

gone major abdominal and thoracic morphine dosing schedule accounts scale consists of 6 behavioral items18:

(noncardiac) surgery. The aim of this for age-related changes in morphine alertness; calmness/agitation; crying or,

trial was to determine if intravenous clearance in addition to weight; eg, a in case of artificial ventilation, breath-

paracetamol would reduce the cumu- 10-kg infant would receive 16 g/kg ing reaction; physical movements;

lative morphine dose needed to pro- per hour, a 5-kg infant, 11 g/kg per muscle tone; and facial tension. A

vide adequate analgesia by at least 30%. hour; an infant weighing 3 kg and trained intensive care nurse observes a

older than 10 days, 9 g/kg per hour; patient for a 2-minute period, during

METHODS and an infant weighing 3 kg and aged which all items are assessed on a 5-point

Patients 10 days or younger, 4 g/kg per numerical scale (1-5). The most dis-

Inthissingle-center,randomized,double- hour. 13,14 For comparison, interna- tressed behavior during the 2-minute

blind study, all children younger than 1 tional guidelines15 suggest 10 to 30 period is scored, resulting in a total

year undergoing major thoracic (noncar- g/kg per hour. score of 6 to 30.

diac) or abdominal surgery between In both study groups, rescue mor- Pain is indicated with an NRS-11

March 2008 and July 2010 at the Eras- phine (patients aged 0 through 10 days, score of 4 or greater. Distress is indi-

mus MC–Sophia Children’s Hospital in 10 g/kg; patients aged 11 days to 1 cated with an NRS-11 score less than

Rotterdam,theNetherlands,wereeligible year, 15 g/kg) was administered when- 4 and COMFORT-B score of 17 or

forinclusion.Inclusioncriteriawerepost- ever Numeric Rating Scale-11 (NRS- greater. Interrater reliability had been

conceptual age of 36 1/7 week or older 11) and COMFORT-Behavior Scale established on the basis of 10 paired ob-

to 1 year of age; body weight greater than (COMFORT-B) scores indicated pain. servations with a nurse already trained.

1500 g; and undergoing major thoracic Rescue doses were administered every A linear weighted Cohen greater than

(noncardiac) or abdominal surgery. 10 minutes when needed, with a maxi- 0.65 was found for all nurses. The me-

Exclusion criteria were extracorpo- mum of 3 per hour. If pain persisted, a dian scored linear weighted for the

real membrane oxygenation treat- continuous morphine rescue infusion COMFORT-B scale was 0.79 (inter-

ment; neurologic dysfunction, he- was started at 1.25 g/kg1.5 per hour quartile range [IQR], 0.72-0.86).

patic dysfunction, or renal insufficiency; (patients aged 0 through 10 days) or 2.5 The Surgical Stress Score was com-

prenatal or postnatal administration of g/kg1.5 per hour (patients aged 11 days puted by the surgeon; scores range from

opioids or psychotropic drugs (anti- to 1 year), after a loading dose of 100 3 to 22, with higher scores indicating

epileptics, benzodiazepines, antidepres- g/kg. When patients then still needed more severe surgical stress.21

sants) for more than 24 hours; known rescue morphine 3 times per hour, the

allergy to or intolerance for paracetamol infusion dose was doubled. Eventu- Randomization and Blinding

or morphine; and administration of opi- ally, if pain persisted in spite of the res- Patients had an equal probability of as-

oids in the 24 hours prior to surgery. cue morphine boluses and the continu- signment to study groups. Stratified ran-

The study was approved by the Eras- ous morphine infusion at a maximum domization was used in combination

mus MC ethics review board; written dose, fentanyl was started. If pain de- with random permuted blocks. Ini-

informed consent from parents or le- creased, as documented by NRS-11 tially, we stratified for 4 age groups: 0

gal representatives was obtained. scores below 4 for more than 12 hours, to 10 days, 11 days to 3 months, 3 to 6

morphine dosage was reduced by 50%. months, and 6 to 12 months. A hospi-

Study Design In case of discomfort (COMFORT-B tal pharmacist carried out computer

Patients were randomized to receive score ⱖ17 and NRS-11 score ⬍4), mid- randomization in advance, and codes

either morphine or paracetamol post- azolam was started. were safely stored. Inclusion numbers

150 JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 ©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

INTRAVENOUS PARACETAMOL IN NEONATES AND INFANTS

for the second, third, and fourth age Study End Points hours to 336 g/kg per hour, based on

groups were falling behind after 9 The primary end point was the cumu- previous data)24 in the intravenous

months of inclusion (18 included in the lative morphine dose, ie, the sum of the paracetamol group compared with the

first group, 2 in the second, 11 in the intraoperative loading dose, the mor- morphine group clinically relevant.

third, 3 in the fourth). We then de- phine study dose, and the rescue mor- Using these assumptions, the number

cided to randomize into 2 age groups: phine doses. of patients required in each group

0 through 10 days and 11 days to 1 year, Secondary end points were mor- equaled 32, as shown by a power analy-

because major changes in pharmaco- phine rescue dose in micrograms per sis in which the ␣ level of significance

kinetics of morphine are to be ex- kilogram in the first 48 hours postop- was fixed at .05 (2-tailed) and the

pected in the first 10 days of life, with eratively, number of extra rescue mor- level was fixed at .20. Considering a

relatively minor changes thereafter.13 phine doses and infusions (each res- dropout rate of 15%, 37 patients per

A new randomization schedule was cue dose or rescue dose in combination group were needed.

computer generated by the same phar- with a rescue infusion start or in- Interim Evaluation. The study was

macist. Only the pharmacist had crease counted as one), number of pa- to be discontinued when more than 18

access to group allocation during the tients receiving rescue doses, average patients would have needed a rescue

study period, for preparation of study NRS-11 and COMFORT-B scores, and morphine infusion (ie, 3 doses of mor-

medication. morphine-related adverse effects. phine and start of background mor-

Morphine-related adverse effects phine). This cutoff was chosen be-

Standardized Anesthesia were defined as (1) need for mechani- cause in this situation both intravenous

Anesthesia was induced by thiopental cal ventilation, reintubation, or both; paracetamol and the morphine start-

(3-5 mg/kg) or by inhalation with sevo- (2) apnea, defined as oxygen satura- ing dose were inadequate as primary

flurane in air/oxygen mixture. Fentanyl tion by pulse oximetry less than 94% analgesia.

(2-5 g/kg) was administered before tra- or respiratory rate less than 20 The pharmacist and the statistician

cheal intubation, with a cumulative total breaths/min longer than 30 seconds; performed this interim evaluation af-

dose of 5 g/kg before the surgical pro- (3) naloxone administration; (4) bra- ter inclusion of 20 patients; the phar-

cedure. Tracheal intubation was facili- dycardia, defined as heart rate less macist, statistician, and investigators re-

tated with cis-atracurium (0.15 mg/kg), than 80 beats/min and more than 30 mained blinded.

except for rapid-sequence inductions, for seconds per episode other than attrib- Statistical Analysis. Descriptive

which succinylcholine (2 mg/kg) was ad- utable to or directly related to the dis- statistics served to compare clinical

ministered. Anesthesia was maintained ease or operation; (5) hypotension, characteristics. The Kolmogorov-

with oxygen/air and isoflurane, titrated defined as need for vasoactive medica- Smirnov test served to assess distribu-

to an end tidal concentration of 0.8% to tion or additional fluid boluses; (6) tion of the variables. Groups were

1.2%. Extra doses of fentanyl (2 g/kg) seizures, when other causes could be compared using t test or Mann-

were administered when heart rate or ruled out; (7) gastrointestinal adverse Whitney test. Odds ratios and 95% CIs

mean arterial blood pressure was 10% or effects, defined as ileus signs or need were estimated to compare groups

more above baseline values. Periopera- for antiemetics or laxatives; and (8) with respect to adverse events as

tive fluids were given in a standardized urinary retention. dichotomous variables (yes/no). Other

way, and normoglycemia was main- proportions were compared by using

tained alongside normothermia (35.5⬚C Clinical Data Collection 2 tests with continuity correction or

to 37⬚C). Clinical data collected were sex, age at using Fisher exact test when appropri-

All patients received a loading dose surgery, body weight, duration and type ate. Level of significance was set at .05,

of morphine (100 g/kg) 30 minutes of surgery (thoracic or abdominal), co- 2-sided.

before the anticipated end of the sur- medication, mechanical ventilation Statistical analyses were performed

gical procedure. Postoperatively they postoperatively, severity-of-illness using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc).

were directly transferred to the inten- scores (Pediatric Risk of Mortality 3, for

sive care unit, where study medica- which higher scores indicate higher risk RESULTS

tion was started within 5 minutes af- of mortality [maximum score, 74], and Patient Characteristics

ter arrival. An attempt to extubate all Pediatric Index of Mortality 2, for which We initially enrolled 74 patients. How-

patients was made in the operating the score [%] indicates the predicted ever, informed consent was with-

room. When extubation was not fea- death rate).22,23 drawn in 1 patient before start of the

sible in the operating room, patients study procedure, 1 patient eventually

were extubated in the intensive care Statistical Methods did not undergo major surgery (no in-

unit as soon as spontaneous breathing Power Analysis. We considered a 30% tussusception present at laparos-

was sufficient, per the attending phy- reduction in cumulative morphine copy), and 1 patient had blood test re-

sician’s judgment. dose (from 480 [SD, 200] g/kg per 48 sults obtained just before surgery that

©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 151

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

INTRAVENOUS PARACETAMOL IN NEONATES AND INFANTS

revealed abnormal liver function sure of congenital diaphragmatic her- curonium, on account of which the

(FIGURE 1). nia and repair of intestinal atresia and NRS-11 and the COMFORT-B could

The characteristics of the remain- esophageal atresia. not be applied, and therefore the study

ing 71 patients did not differ signifi- One patient with gastroschisis in the medication was terminated and re-

cantly between the paracetamol and paracetamol group underwent addi- placed by morphine after 19 hours and

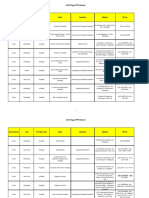

morphine groups (TABLE 1). The most tional surgery for bowel necrosis. This cumulative morphine dose was calcu-

frequent surgical procedures were clo- patient postoperatively received ve- lated for the first 48 hours postopera-

tively (intention-to-treat).

Figure 1. Study Flow Study End Points

The cumulative morphine dose in the

248 Neonates and infants assessed

for eligibility paracetamol group was 66% (95% CI,

34% to 109%) lower than that in the

174 Excluded morphine group (median, 121 [IQR,

109 Did not meet inclusion criteria 99-264] g/kg per 48 hours vs 357

47 Received opioids 24 h prior to surgery

20 Premature [IQR, 220-605] g/kg per 48 hours;

13 Required extracorporeal membrane P ⬍ .001) (TABLE 2, FIGURE 2). Con-

oxygenation

12 No major surgery sidering the 2 stratified age groups sepa-

10 Neurologic dysfunction, hepatic

dysfunction, or renal insufficiency

rately, the cumulative morphine dose

7 Emergency surgery in the paracetamol group was 49% (95%

36 Logistic reasons

29 Refused to participate

CI, ⫺6% to 89%) lower than that in the

morphine group for the neonates (aged

0 through 10 days) (median, 111 [IQR,

74 Randomized

96-169] g/kg per 48 hours vs 218

[IQR, 186-294] g/kg per 48 hours;

35 Randomized to receive paracetamol 39 Randomized to receive morphine

33 Received paracetamol as randomized 38 Received morphine as randomized

P = .002) and 73% (95% CI, 30% to

2 Did not receive paracetamol 1 Did not receive morphine (no major 114%) lower for the older infants (aged

1 Abnormal liver function surgery)

1 Withdrew informed consent 11 days to 1 year) (median, 152 [IQR,

112-346] g/kg per 48 hours vs 553

33 Included in primary analysis 38 Included in primary analysis [IQR, 361-765] g/kg per 48 hours;

2 Excluded

1 Abnormal liver function

1 Excluded (no major surgery) P⬍ .001).

1 Withdrew informed consent The total morphine rescue dose did

not differ significantly between the

paracetamol and morphine groups (me-

Table 1. Patient Characteristics dian, 25 [IQR, 0-164] g/kg per 48

No. (%) hours vs 20 [IQR, 0-226] g/kg per 48

hours; P = .99). The amount or num-

Paracetamol Morphine P

Characteristic (n = 33) (n = 38) Value ber of morphine rescue doses, and the

Sex number of patients requiring rescue

Male 18 (54.5) 26 (68.4)

.23

doses, also did not differ (Table 2).

Female 15 (45.5) 12 (31.6) We found no significant differences

Age at surgery, median (IQR), d 5 (1.5-64.5) 20 (1.8-87.5) .50 for percentage of adverse effects be-

Age, d tween treatment groups (27.3% for

ⱕ10 17 (51.5) 18 (47.4)

.73 paracetamol vs 34.2% for morphine;

⬎10 16 (48.5) 20 (52.6)

odds ratio, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.3 to 2.6])

Weight, mean (SD), kg 3.8 (1.3) 4.4 (2.0) .17

(Table 2). Naloxone was adminis-

Duration of surgery, mean (SD), min 172.1 (83.7) 156.6 (87.9) .45

tered 3 times in the morphine group

Surgical procedure

Thoracic 5 (15.2) 11 (28.9) and not at all in the paracetamol group.

.17

Abdominal 28 (84.8) 27 (71.1) No seizures, hypotension, or gastroin-

Postoperative mechanical ventilation 15 (45.5) 14 (36.8) .46 testinal adverse effects occurred.

Duration of postoperative ventilation, median (IQR), h 34 (15-45) 23 (16-45) .43 The median NRS-11 and mean

Surgical stress score, median (IQR) 10 (9-11) 10 (9-11) .75 COMFORT-B scores were similar in

PRISM3, median (IQR) 2 (0-4.5) 3.0 (0-5.0) .91 both groups (1 [IQR, 0-1] vs 1 [IQR,

PIM2, median (IQR), % risk of mortality 1.3 (0.6-1.9) 1.4 (0.7-2.4) .34 0-2]; P=.17] and 13.0 [SD, 2.0] vs 13.1

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PIM2, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2; PRISM3, Pediatric Risk of Mortality 3. [SD, 2.1]; P =.80, respectively).

152 JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 ©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

INTRAVENOUS PARACETAMOL IN NEONATES AND INFANTS

COMMENT

Table 2. End Points in First 48 Postoperative Hours

This randomized controlled trial shows

No. (%)

that infants who receive intravenous

paracetamol as primary analgesic after Paracetamol Morphine P

End Point (n = 33) (n = 38) Value OR (95% CI)

major surgery require significantly less

Cumulative morphine dose, median 121 (99-264) 357 (220-605) ⬍.001

morphine than those who receive a con- (IQR), g/kg

tinuous morphine infusion. Judging Rescue morphine dose, median 25 (0-164) 20 (0-226) .99

from the rescue morphine doses, a simi- (IQR), g/kg

lar level of analgesia was obtained in Rescue morphine doses and 2 (0-6) 2 (0-5) .97

either group. These results suggest that infusions, median (IQR), No.

intravenous paracetamol may be an in- Patients receiving rescue 22 (66.77) 23 (60.5) .59

morphine

teresting alternative as primary anal- Comedication

gesic in neonates and infants. Midazolam 5 (15.2) 3 (7.9) .34

The opioid-sparing potential of Fentanyl 0 1 (2.6) .35

paracetamol was shown in older chil- Vecuronium 1 (3.0) 0 .28

dren and adults. Hong et al11 found a Locoregional block 0 3 (7.9) .10

fentanyl-sparing effect of intravenous Adverse events

paracetamol in infants aged 6 to 24 Any adverse event 9 (27.3) 11 (28.9) 0.9 (0.3-2.6)

months using parent- or nurse- Reintubation 1 (3.0) 2 (5.3) 0.6 (0.1-6.5)

controlled analgesia after ureteroneo- Apnea 4 (12.1) 10 (26.3) 0.5 (0.1-1.9)

cystostomy. In older children, Kor- Apnea with naloxone 0 3 (7.9) 0.5 (0.4-0.7)

pela et al25 showed that a single dose of Bradycardia 6 (18.2) 7 (18.4) 1.0 (0.3-3.3)

40 or 60 mg/kg of rectal acetamino- Urinary retention a 1 0 0.5 (0.4-0.6)

phen has a clear morphine-sparing Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio.

a Twenty-six patients in the paracetamol group and 31 in the morphine group had a urinary catheter in place.

effect in outpatient surgery for older

children, if administered during the

induction of anesthesia. A recent sys- Paracetamoldidnotinducerespiratory

Figure 2. Cumulative Morphine Dose for

tematic review showed a morphine- depression, an adverse effect observed in Morphine and Paracetamol Study Groups

sparing effect of paracetamol (oral, rec- 3patientsinthemorphinegroup.Despite Over 48 Postoperative Hours

tal, or intravenous) in adult patients a lack of statistical significance for this

receiving morphine as postoperative and other adverse effects, this observa- 2000

patient-controlled analgesia. The reduc- tion does suggest a potential reduction

tion of morphine requirements was in respiratory depression with use of

Cumulative Morphine Dose,

1500

lower than in our study (14% vs 66%).26 paracetamol. The systematic review in

In contrast, other studies did not adults also found no significant reduc-

µg/kg per 48 h

find a morphine-sparing effect of rec- tion in morphine-related adverse effects, 1000

tal paracetamol, either in young despite a reduction in cumulative mor-

infants (0-2 months) 10 or in older phine dose administered postopera-

children.27-29 We speculate that type of tively.26 This phenomenon may be ex- 500

study design may partly explain the plained by a lack of power, because most

contrasting findings. In most studies studies were designed to detect a differ-

baseline standard opioid infusions ence in efficacy but not in adverse effects. 0

Paracetamol Morphine

were administered in both study Also, in many studies, adverse effects are (n = 33) (n = 38)

groups,10,11,29 potentially blurring the not systematically reported.26

actual effect of paracetamol. In our A reduction of opioid-related ad- Boxes indicate medians (horizontal lines) and in-

terquartile ranges; error bars, 10th and 90th per-

study, apart from the intraoperative verse events may be mitigated by an in- centiles. Open black circles indicate outliers with

morphine loading dose, paracetamol creased risk of paracetamol-related ad- values more than 1.5 times the height of the boxes;

solid black circles, extreme outliers with values

was given as primary analgesic with verse events. Using the dosing regimen more than 3 times the height of the boxes. Two

morphine rescue as a possibility. Fur- of this study, plasma concentrations are extreme outliers were identified in the paracetamol

group, the first a boy aged 68 days who underwent

thermore, differences in paracetamol expected to be similar to those ob- surgery for long-gap esophageal atresia and subse-

formulations used may result in vari- tained with rectal acetaminophen dos- quently needed a chest tube for a pneumothorax

able absorption and plasma concentra- ing.30,31 Therefore, although evidence of and the second a newborn boy with a gastroschisis

for which a silo was placed. One extreme outlier

tions. These limitations are overcome safety specifically for intravenous was identified in the morphine group, a girl aged

by the intravenous administration in paracetamol in neonates is limited,32 it 355 days who underwent surgery for a recurrence

of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

our study. is unlikely that it is associated with

©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 153

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

INTRAVENOUS PARACETAMOL IN NEONATES AND INFANTS

more toxicity than rectal paracetamol. ternal validity of the findings.36 Second, Analysis and interpretation of data: Ceelie, de Wildt,

van Dijk, van den Berg, Duivenvoorden, Mathôt,

The general safety of paracetamol in as discussed above, this study was not Knibbe.

neonates and children has been widely powered to detect a difference in ad- Drafting of the manuscript: Ceelie, van Dijk, van den

Berg.

documented.33 More specifically, neo- verse effects, nor were we able to moni- Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-

nates have a lower risk of paracetamol- tor liver function in the paracetamol tellectual content: de Wildt, van Dijk, van den Bosch,

induced hepatotoxicity than have older group. This limits our ability to deter- Duivenvoorden, de Leeuw, Mathôt, Knibbe, Tibboel.

Statistical analysis: Ceelie, van Dijk, Duivenvoorden.

children and adults because the en- mine which treatment was safest. Obtained funding: de Wildt, Knibbe, Tibboel.

zymes (eg, CYP2E1) involved in the for- In conclusion, among infants under- Administrative, technical, or material support: Ceelie,

van den Berg, van den Bosch, de Leeuw, Mathôt.

mation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone im- going major surgery, postoperative use Study supervision: de Wildt, van Dijk, Knibbe, Tibboel.

ine, the hepatotoxic metabolite, are still of intermittent intravenous paracetamol Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have com-

pleted and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of

immature.34 A systematic analysis of compared with continuous morphine Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

hepatotoxicity as adverse effect in pe- resulted in a lower cumulative mor- Funding/Suppport: This study was supported

diatric trials of paracetamol could not phine dose over 48 hours. by ZonMw Priority Medicines for Children grant

40-41500-98.9020.

confirm paracetamol-related toxicity Author Contributions: Dr Tibboel had full access to all Role of the Sponsor: ZonMw had no role in the design

when dosed therapeutically.35 of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the and conduct of the study; the collection, manage-

integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ment, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the

Some limitations of our study need Drs Ceelie and de Wildt contributed equally to this work. preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

to be addressed. First, this is a single- Study concept and design: Ceelie, de Wildt, van Dijk, Additional Contributions: We thank Ko Hagoort, MA

van den Berg, Knibbe. (Erasmus MC–Sophia Children’s Hospital), for edi-

center study in a strictly defined patient Acquisition of data: Ceelie, van den Berg, van den torial assistance. Mr Hagoort received no compensa-

population. This may potentially limit ex- Bosch, de Leeuw, Tibboel. tion for his contributions.

REFERENCES

1. Anand KJ, Hickey PR. Pain and its effects in the hu- tiveperformanceofarecentlydevelopedpopulationphar- 26. Maund E, McDaid C, Rice S, Wright K, Jenkins B,

man neonate and fetus. N Engl J Med. 1987;317 macokinetic model for morphine and its metabolites in Woolacott N. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective

(21):1321-1329. new datasets of (preterm) neonates, infants and children. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the reduction

2. Anand KJ, Sippell WG, Aynsley-Green A. Randomised Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(1):51-63. in morphine-related side-effects after major surgery:

trial of fentanyl anaesthesia in preterm babies undergo- 15. Anand KJ; International Evidence-Based Group for a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(3):292-

ing surgery: effects on the stress response. Lancet. 1987; Neonatal Pain. Consensus statement for the prevention 297.

1(8524):62-66. and management of pain in the newborn. Arch Pediatr 27. Bremerich DH, Neidhart G, Heimann K, Kessler P,

3. Berry FA, Gregory GA. Do premature infants require Adolesc Med. 2001;155(2):173-180. Behne M. Prophylactically-administered rectal aceta-

anesthesia for surgery? Anesthesiology. 1987;67 16. van Dijk M, Peters JW, van Deventer P, Tibboel D. minophen does not reduce postoperative opioid re-

(3):291-293. The COMFORT Behavior Scale: a tool for assessing pain quirements in infants and small children undergoing

4. Weisman SJ, Bernstein B, Schechter NL. Consequences and sedation in infants. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(1): elective cleft palate repair. Anesth Analg. 2001;92

of inadequate analgesia during painful procedures in 33-36. (4):907-912.

children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(2): 17. Valkenburg AJ, Boerlage AA, Ista E, Duivenvoorden 28. Korpela R, Silvola J, Laakso E, Meretoja OA. Oral

147-149. HJ, Tibboel D, van Dijk M. The COMFORT-Behavior scale naproxen but not oral paracetamol reduces the need for

5. Berde CB, Sethna NF. Analgesics for the treatment of is useful to assess pain and distress in 0- to 3-year-old chil- rescue analgesic after adenoidectomy in children. Acta

pain in children [published correction appears in N Engl dren with Down syndrome. Pain. 2011;152(9):2059- Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(6):726-730.

J Med. 2011;364(18):1782]. N Engl J Med. 2002; 2064. 29. Morton NS, O’Brien K. Analgesic efficacy of

347(14):1094-1103. 18. van Dijk M, de Boer JB, Koot HM, Tibboel D, Passchier paracetamol and diclofenac in children receiving PCA

6. Taddio A, Katz J, Ilersich AL, Koren G. Effect of neonatal J, Duivenvoorden HJ. The reliability and validity of the morphine. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82(5):715-717.

circumcision on pain response during subsequent rou- COMFORT scale as a postoperative pain instrument in 30. Palmer GM, Atkins M, Anderson BJ, et al. I.V. ac-

tine vaccination. Lancet. 1997;349(9052):599-603. 0- to 3-year-old infants. Pain. 2000;84(2-3):367- etaminophen pharmacokinetics in neonates after mul-

7. Booker PD. Postoperative analgesia for neonates? 377. tiple doses. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(4):523-530.

Anaesthesia. 1987;42(4):343-344. 19. Bai J, Hsu L, Tang Y, van Dijk M. Validation of the 31. Anderson BJ, van Lingen RA, Hansen TG, Lin YC,

8. Berde CB, Jaksic T, Lynn AM, Maxwell LG, Soriano COMFORT Behavior scale and the FLACC scale for pain Holford NH. Acetaminophen developmental pharma-

SG, Tibboel D. Anesthesia and analgesia during and af- assessment in Chinese children after cardiac surgery. Pain cokinetics in premature neonates and infants: a pooled

ter surgery in neonates. Clin Ther. 2005;27(6):900- Manag Nurs. 2012;13(1):18-26. population analysis. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(6):

921. 20. von Baeyer CL, Spagrud LJ, McCormick JC, Choo 1336-1345.

9. Taddio A, Shah V, Gilbert-MacLeod C, Katz J. Con- E, Neville K, Connelly MA. Three new datasets support- 32. AllegaertK,RayyanM,DeRijdtT,VanBeekF,Naulaers

ditioning and hyperalgesia in newborns exposed to re- ing use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for chil- G. Hepatic tolerance of repeated intravenous paracetamol

peated heel lances. JAMA. 2002;288(7):857-861. dren’s self-reports of pain intensity. Pain. 2009;143 administration in neonates. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;

10. van der Marel CD, Peters JW, Bouwmeester NJ, (3):223-227. 18(5):388-392.

Jacqz-Aigrain E, van den Anker JN, Tibboel D. Rectal 21. Anand KJ, Aynsley-Green A. Measuring the sever- 33. Amar PJ, Schiff ER. Acetaminophen safety and

acetaminophen does not reduce morphine consumption ity of surgical stress in newborn infants. J Pediatr Surg. hepatotoxicity—where do we go from here? Expert Opin

after major surgery in young infants. Br J Anaesth. 2007; 1988;23(4):297-305. Drug Saf. 2007;6(4):341-355.

98(3):372-379. 22. Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an 34. James LP, Capparelli EV, Simpson PM, et al; Net-

11. Hong JY, Kim WO, Koo BN, Cho JS, Suk EH, Kil HK. updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med. work of Pediatric Pharmacology Research Units,

Fentanyl-sparing effect of acetaminophen as a mixture 1996;24(5):743-752. National Institutes of Child Health and Human

of fentanyl in intravenous parent-/nurse-controlled 23. Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G; Paediatric Index of Mor- Development. Acetaminophen-associated hepatic

analgesia after pediatric ureteroneocystostomy. tality (PIM) Study Group. PIM2: a revised version of the injury: evaluation of acetaminophen protein adducts

Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):672-677. Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2003; in children and adolescents with acetaminophen

12. Murat I, Baujard C, Foussat C, et al. Tolerance and 29(2):278-285. overdose. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(6):684-

analgesic efficacy of a new I.V. paracetamol solution in 24. Bouwmeester NJ, van den Anker JN, Hop WC, Anand 690.

children after inguinal hernia repair. Paediatr Anaesth. KJ, Tibboel D. Age- and therapy-related effects on 35. Lavonas EJ, Reynolds KM, Dart RC. Therapeutic

2005;15(8):663-670. morphine requirements and plasma concentrations of acetaminophen is not associated with liver injury in chil-

13. Knibbe CA, Krekels EH, van den Anker JN, et al. Mor- morphine and its metabolites in postoperative infants. dren: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126

phine glucuronidation in preterm neonates, infants and Br J Anaesth. 2003;90(5):642-652. (6):e1430-e1444.

children younger than 3 years. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009; 25. Korpela R, Korvenoja P, Meretoja OA. Morphine- 36. Bellomo R, Warrillow SJ, Reade MC. Why we should

48(6):371-385. sparing effect of acetaminophen in pediatric day-case be wary of single-center trials. Crit Care Med. 2009;

14. Krekels EH, DeJongh J, van Lingen RA, et al. Predic- surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;91(2):442-447. 37(12):3114-3119.

154 JAMA, January 9, 2013—Vol 309, No. 2 ©2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Suzan Sacar on 05/21/2019

You might also like

- The Analgesic Efficacy of Tramadol As A Pre-Emptive Analgesic in Pediatric Appendectomy Patients PDFDocument6 pagesThe Analgesic Efficacy of Tramadol As A Pre-Emptive Analgesic in Pediatric Appendectomy Patients PDFUmmu Qonitah AfnidawatiNo ratings yet

- 2049 9752 4 1Document5 pages2049 9752 4 1Nasrull BinHzNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument6 pagesJournal ReadingInka Nadya TriayeshaNo ratings yet

- Aei 156Document4 pagesAei 156ErickNo ratings yet

- Jurnal UklinDocument7 pagesJurnal UklinHestiDwiFajriyantiNo ratings yet

- Wu 2022Document12 pagesWu 2022Walaa YousefNo ratings yet

- A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing Remifentanil With Fentanyl in Mechanically Ventilated PatientsDocument8 pagesA Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing Remifentanil With Fentanyl in Mechanically Ventilated PatientsJosé Carlos Sánchez-RamirezNo ratings yet

- A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing Remifentanil With Fentanyl in Mechanically Ventilated PatientsDocument8 pagesA Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing Remifentanil With Fentanyl in Mechanically Ventilated PatientsJosé Carlos Sánchez-RamirezNo ratings yet

- Paracetamol Commentary 0409Document5 pagesParacetamol Commentary 0409Meidy WerorNo ratings yet

- Ircmj 15 9267Document6 pagesIrcmj 15 9267samaraNo ratings yet

- 185852-Article Text-472571-1-10-20190423 PDFDocument9 pages185852-Article Text-472571-1-10-20190423 PDFPablo Segales BautistaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Ibuprofen Versus Aspirin and Paracetamol On Efficacy and Comfort in Children With FeverDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Ibuprofen Versus Aspirin and Paracetamol On Efficacy and Comfort in Children With FeverlilingNo ratings yet

- Adherence To Oral Hypoglycemic MedicatioDocument20 pagesAdherence To Oral Hypoglycemic Medicatioashenafi woldesenbetNo ratings yet

- Propranolol For HemangiomaDocument8 pagesPropranolol For Hemangiomaansar ahmedNo ratings yet

- BjorlDocument6 pagesBjorlaaNo ratings yet

- Intravenous Infusion of Paracetamol For Intrapartum AnalgesiaDocument6 pagesIntravenous Infusion of Paracetamol For Intrapartum AnalgesiaDaniel Rincón VillateNo ratings yet

- Mammae 2 PDFDocument6 pagesMammae 2 PDFAdila YulianiNo ratings yet

- Farmacocinética Propofol PDFDocument9 pagesFarmacocinética Propofol PDFFrancisco Ferrer TorresNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Intramuscular Diamorphine and Intramuscular Pethidine For Labour Analgesia: A Two-Centre Randomised Blinded Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesA Comparison of Intramuscular Diamorphine and Intramuscular Pethidine For Labour Analgesia: A Two-Centre Randomised Blinded Controlled TrialWinda ResmythaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Ketamine-Midazolam-Propofol Combination and Fentanyl-Midazolam-Propofol Combination For Sedation in ColonosDocument8 pagesComparison of Ketamine-Midazolam-Propofol Combination and Fentanyl-Midazolam-Propofol Combination For Sedation in ColonosDendy AgusNo ratings yet

- Anes 10Document8 pagesAnes 10Fuchsia ZeinNo ratings yet

- Ketamin Vs MorfinDocument9 pagesKetamin Vs MorfinKhusnul KhotimahNo ratings yet

- dst50234 PDFDocument7 pagesdst50234 PDFtaniaNo ratings yet

- MRN000410 BnCWy5eDocument11 pagesMRN000410 BnCWy5eAn JNo ratings yet

- 与扑热息痛联用增效Document5 pages与扑热息痛联用增效zhuangemrysNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Gerd 3Document6 pagesJurnal Gerd 3sega maulanaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric PharmacotherapyDocument4 pagesPediatric PharmacotherapyRiriNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth.-2008-Mathiesen-535-41Document7 pagesBr. J. Anaesth.-2008-Mathiesen-535-41Kunal DhurveNo ratings yet

- FentanylDocument12 pagesFentanylUtomo FemtomNo ratings yet

- Dopamine Vs EpinephrineDocument11 pagesDopamine Vs EpinephrineAyiek WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2352556818300389 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2352556818300389 Main吴善统No ratings yet

- A-Acta Paediatr 2010 Apr 99 (4) 497-501Document5 pagesA-Acta Paediatr 2010 Apr 99 (4) 497-501Antonio MartinezNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDocument4 pagesEfficacy of Dexamethasone For Reducing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Analgesic Requirements After ThyroidectomyDr shehwarNo ratings yet

- 2015 Article 20Document7 pages2015 Article 20ardianNo ratings yet

- A RCT of Oral Propranolol in Infantile HemangiomaDocument12 pagesA RCT of Oral Propranolol in Infantile HemangiomaIndahNovikaNo ratings yet

- Circulatory ShockDocument5 pagesCirculatory ShockmaudyNo ratings yet

- IndomethacinDocument5 pagesIndomethacinDian NovitasariNo ratings yet

- Warfarin With ParacetamolDocument4 pagesWarfarin With ParacetamolChintia GautamaNo ratings yet

- 404 2019 Article 5260Document7 pages404 2019 Article 5260Farida SiggiNo ratings yet

- Babalik. Serum drug concentration Turkey. IJTLD Dec 13Document7 pagesBabalik. Serum drug concentration Turkey. IJTLD Dec 13Vigilancia EpidemiologicaNo ratings yet

- E1252 FullDocument7 pagesE1252 FullwawanNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Ambulatory Epidurals, Labour Analgesia, Recent AdvancesDocument12 pagesKeywords: Ambulatory Epidurals, Labour Analgesia, Recent Advancesmanish086No ratings yet

- 27-ดวงกมลชนก - อภิสราวรรณ-Erenumab Versus Topiramate for the Prevention of Migraine - a Randomised, Double-blind, Active-controlled Phase 4 TrialDocument11 pages27-ดวงกมลชนก - อภิสราวรรณ-Erenumab Versus Topiramate for the Prevention of Migraine - a Randomised, Double-blind, Active-controlled Phase 4 TrialPleng DuangkamolchanokNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Caudal Morphine and Tramadol For Postoperative Pain Control in Children Undergoing Inguinal HerniorrhaphyDocument6 pagesComparison of Caudal Morphine and Tramadol For Postoperative Pain Control in Children Undergoing Inguinal Herniorrhaphymanoj9980No ratings yet

- Bmri2015 465465Document5 pagesBmri2015 465465nadaNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Labour AnalgesiaDocument17 pagesRecent Advances in Labour Analgesiamanish086No ratings yet

- Jurnal AnestesiDocument8 pagesJurnal AnestesiapriiiiiiilllNo ratings yet

- Proposal For The Inclusion of Anti-Emetic Medications (For Children) in The Who Model List of Essential MedicinesDocument44 pagesProposal For The Inclusion of Anti-Emetic Medications (For Children) in The Who Model List of Essential MedicinesJennifer FaustinNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Intravenous Paracetamol (Propacetamol) Pharmacokinetics: A Population AnalysisDocument11 pagesPediatric Intravenous Paracetamol (Propacetamol) Pharmacokinetics: A Population AnalysisWahyu IndraNo ratings yet

- A New Approach To The Prophylaxis of Cyclic Vomiting TopiramateDocument5 pagesA New Approach To The Prophylaxis of Cyclic Vomiting TopiramateVianNo ratings yet

- Tiva en Neonatos y Niños2019Document19 pagesTiva en Neonatos y Niños2019Laura Camila RiveraNo ratings yet

- 1305 FullDocument4 pages1305 FullBryan De HopeNo ratings yet

- Deep Sedation During Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Propofol-Fentanyl and Midazolam-Fentanyl RegimensDocument8 pagesDeep Sedation During Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Propofol-Fentanyl and Midazolam-Fentanyl RegimensiweNo ratings yet

- Impact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyDocument8 pagesImpact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyMiftah Furqon AuliaNo ratings yet

- AnesDocument8 pagesAnesrachma30No ratings yet

- MitraDocument6 pagesMitraVan DaoNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Propranolol Between 6 and 12 Months of Age in High Risk Infantile HemangiomDocument10 pagesEfficacy of Propranolol Between 6 and 12 Months of Age in High Risk Infantile HemangiomNoviaNo ratings yet

- Murphy Et Al-2016-Pediatric Anesthesia PDFDocument5 pagesMurphy Et Al-2016-Pediatric Anesthesia PDFBijay KumarNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream (EMLA) in The Treatment of Acute Pain in NeonatesDocument11 pagesA Systematic Review of Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream (EMLA) in The Treatment of Acute Pain in NeonatesmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Trauma Chapter 5Document49 pagesTrauma Chapter 5Bimantoro SaputroNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and Outcome of Mandibular Fracture Reduction Without and With An Aid of A Repositioning ForcepsDocument8 pagesAccuracy and Outcome of Mandibular Fracture Reduction Without and With An Aid of A Repositioning ForcepsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- 35 A EllisDocument2 pages35 A EllismustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Changing Trends in The Treatment of Mandibular Fracture: Mohammad Waheed El-AnwarDocument2 pagesChanging Trends in The Treatment of Mandibular Fracture: Mohammad Waheed El-AnwarmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and Outcome of Mandibular Fracture Reduction Without and With An Aid of A Repositioning ForcepsDocument8 pagesAccuracy and Outcome of Mandibular Fracture Reduction Without and With An Aid of A Repositioning ForcepsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Mandible Fractures: Brent B. Pickrell, MD Arman T. Serebrakian, MD, MS Renata S. Maricevich, MDDocument8 pagesMandible Fractures: Brent B. Pickrell, MD Arman T. Serebrakian, MD, MS Renata S. Maricevich, MDmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- 9-Is The Use of Kinesio Tape (KT) Effective in Improving Gross MotoDocument15 pages9-Is The Use of Kinesio Tape (KT) Effective in Improving Gross MotomustafasacarNo ratings yet

- 10 Jpts 27 1455Document3 pages10 Jpts 27 1455mustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Fixation of Mandibular Angle Fractures: in Vitro Biomechanical Assessments and Computer-Based StudiesDocument19 pagesFixation of Mandibular Angle Fractures: in Vitro Biomechanical Assessments and Computer-Based StudiesmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Taping On Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesThe Effectiveness of Taping On Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Effects of Kinesio Taping On The Gait Parameters of Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot StudyDocument5 pagesEffects of Kinesio Taping On The Gait Parameters of Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot StudymustafasacarNo ratings yet

- We Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDocument31 pagesWe Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- In The: Evidence ForDocument7 pagesIn The: Evidence FormustafasacarNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Kinesio Taping Technique On Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Kinesio Taping Technique On Children With Cerebral PalsymustafasacarNo ratings yet

- 6-Effects of Kinesiology Taping in Children With CerDocument10 pages6-Effects of Kinesiology Taping in Children With CermustafasacarNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Taping On Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesThe Effectiveness of Taping On Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- 3 13059 ArticleText 24188 2 10 20191119Document9 pages3 13059 ArticleText 24188 2 10 20191119mustafasacarNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Long-Term Behavioral Effects of Repetitive Pain in Neonatal Rat PupsDocument25 pagesNIH Public Access: Long-Term Behavioral Effects of Repetitive Pain in Neonatal Rat PupsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Randomised trial of sucrose, glucose, and pacifiers for neonatal pain reliefDocument5 pagesRandomised trial of sucrose, glucose, and pacifiers for neonatal pain reliefmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Summary Proceedings From The Neonatal Pain-Control Group: Supplement ArticleDocument16 pagesSummary Proceedings From The Neonatal Pain-Control Group: Supplement ArticlemustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Blood Sampling in Infants (Reducing Pain and Morbidity) : Olga KapellouDocument18 pagesBlood Sampling in Infants (Reducing Pain and Morbidity) : Olga KapelloumustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Smith - Vibration Anesthesia - A Noninvasive Method of Reducing Discomfort Prior To Dermatologic Procedures PDFDocument9 pagesSmith - Vibration Anesthesia - A Noninvasive Method of Reducing Discomfort Prior To Dermatologic Procedures PDFmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Treatment of Painful Procedures in Neonates in Intensive Care UnitsDocument13 pagesEpidemiology and Treatment of Painful Procedures in Neonates in Intensive Care UnitsmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- sTEVENS PDFDocument9 pagessTEVENS PDFmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Managing Pain in Neonatal Intensive CareDocument8 pagesManaging Pain in Neonatal Intensive CaremustafasacarNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Mechanical Vibration Analgesia For Relief of Heel Stick Pain in NeonatesDocument10 pagesThe Efficacy of Mechanical Vibration Analgesia For Relief of Heel Stick Pain in NeonatesmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Sexton PDFDocument5 pagesSexton PDFmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream (EMLA) in The Treatment of Acute Pain in NeonatesDocument11 pagesA Systematic Review of Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream (EMLA) in The Treatment of Acute Pain in NeonatesmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Stevens2 PDFDocument362 pagesStevens2 PDFmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Living Donor Transplantation BrochureDocument13 pagesLiving Donor Transplantation BrochureShani KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Resume, DR - Deepak, Reader (Oral Surgery)Document6 pagesResume, DR - Deepak, Reader (Oral Surgery)lokesh_045No ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Billy Admitted with Ear and Throat InfectionsDocument6 pagesNursing Care Plan for Billy Admitted with Ear and Throat InfectionsNatukunda Dianah100% (1)

- "Monograph Eating Disorders": StudentDocument12 pages"Monograph Eating Disorders": StudentTeffy NeyraNo ratings yet

- Part ADocument41 pagesPart AAmar G PatilNo ratings yet

- Freud's Early Cocaine Use and the Origins of PsychoanalysisDocument26 pagesFreud's Early Cocaine Use and the Origins of PsychoanalysisEmmanuel S. CaliwanNo ratings yet

- 1 - Draft PNS Banana Ketchup Standard For Posting 30oct13Document50 pages1 - Draft PNS Banana Ketchup Standard For Posting 30oct13Julia GaborNo ratings yet

- History of Reconstructive and Aesthetic SurgeryDocument22 pagesHistory of Reconstructive and Aesthetic SurgeryIde Bagoes Insani100% (2)

- RKO-1Document85 pagesRKO-1Muhamad IsmailNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Reverse Roleplay Training To Improve The Counselor's Mind SkillsDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Reverse Roleplay Training To Improve The Counselor's Mind SkillsJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Combination Syndrome Review ArticleDocument5 pagesCombination Syndrome Review ArticlefirginaaNo ratings yet

- Stages of HivDocument4 pagesStages of Hivapi-273431943No ratings yet

- Access Medicine - TableDocument2 pagesAccess Medicine - Tablecode-24No ratings yet

- The Clinical Toxicology of Caffeine: A Review and Case StudyDocument12 pagesThe Clinical Toxicology of Caffeine: A Review and Case Studydita putriNo ratings yet

- Superficial ParotidectomyDocument7 pagesSuperficial ParotidectomySajid Hussain ShahNo ratings yet

- HCL 32Document6 pagesHCL 32Bao Duy NguyenNo ratings yet

- DeliriumDocument27 pagesDeliriumBushra EjazNo ratings yet

- Waste ManagementDocument75 pagesWaste ManagementGururaj Dafale100% (1)

- Vasculitis: ANCA AssociatedDocument14 pagesVasculitis: ANCA AssociatedMahda Adil AufaNo ratings yet

- Asthma Nursing Care Plan - NCP - Ineffective Airway ClearanceDocument2 pagesAsthma Nursing Care Plan - NCP - Ineffective Airway ClearanceCyrus De Asis92% (24)

- Fluoride RemovalDocument16 pagesFluoride RemovalSandeep_AjmireNo ratings yet

- Understanding Frequencies Through Harmonics AssociationsDocument24 pagesUnderstanding Frequencies Through Harmonics Associations1aquila1100% (2)

- ALICO Egypt PPO Network Providers in CairoDocument115 pagesALICO Egypt PPO Network Providers in CairoAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- AmmoniumChloride PDFDocument3 pagesAmmoniumChloride PDFAP TOROBXNo ratings yet

- Oral SurgeryDocument40 pagesOral Surgeryshekinah echavezNo ratings yet

- Endocrine System GlandsDocument40 pagesEndocrine System GlandsSolita PorteriaNo ratings yet

- Microbial Process Heat CalculationDocument8 pagesMicrobial Process Heat Calculationhansenmike698105No ratings yet

- University of Eastern Philippines: University Town, Northern SamarDocument5 pagesUniversity of Eastern Philippines: University Town, Northern SamarJane MinNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study of The Effectiveness of Butterfly Technique of SCENAR Therapy On Heart Rate VariabilityDocument7 pagesPilot Study of The Effectiveness of Butterfly Technique of SCENAR Therapy On Heart Rate VariabilityParallaxsterNo ratings yet