Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar Trauma

Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar Trauma

Uploaded by

GeraldineCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar Trauma

Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar Trauma

Uploaded by

GeraldineCopyright:

Available Formats

The Physician and Sportsmedicine

ISSN: 0091-3847 (Print) 2326-3660 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ipsm20

Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar Trauma

Essential Tips for Treating Active Patients

Kenneth A. Honsik, Kimberly G. Harmon (Practice Essentials Series Editor) &

Aaron Rubin (Practice Essentials Series Editor)

To cite this article: Kenneth A. Honsik, Kimberly G. Harmon (Practice Essentials Series Editor)

& Aaron Rubin (Practice Essentials Series Editor) (2004) Emergency Treatment of Dentoalveolar

Trauma, The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 32:9, 23-29, DOI: 10.1080/00913847.2004.11440732

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2004.11440732

Published online: 19 Jun 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 32

View related articles

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ipsm20

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Emergency Treatment of

Dentoalveolar Trauma

Essential Tips for Treating Active Patients

Kenneth A. Honsik, MD

For CME credit,

Practice Essentials Series Editors: see page 47

Kimberly G. Harmon, MD; Aaron Rubin, MD

II: I: liiIJaDentoalveolar tramna b;~ports is common. One third of dental injuries in the United

States occur in sports-related activities, so team physicians should be able to recognize and

properly treat dental injuries on the field. Tooth fracture, luxation, avulsion, and socket injury

are the main types of dentoalveolar tramna. In many cases, other maxillofacial tramna can be

associated with dental injuries, so physicians who examine these patients should be aware of

additional associated injuries. Tooth injury is often preventable with the appropriate use of

properly fitted mouth guards. Physicians should be familiar with different types and be able to

suggest the correct mouth guard for a given activity.

ental injuries on the athletic

D field are common and can have

serious negative consequences

for an athlete. Prevention is the

key, but proper immediate treatment is

essential. Most athletes have some basic

medical insurance; however, not all ath-

letes have dental insurance. Costs for

improperly treated dental injuries can be

sizable and can also have much higher

complication rates and poor cosmetic results. On-field (CDC) in 2001 estimated that approximately one third

sports medicine providers can diminish poor out- of all dental injuries in the United States are sports

comes through appropriate initial treatment and edu- related.' Studies from other countries provide valuable

cate athletes, parents, and coaches about proper statistics on frequency and type of dental injury. For

prevention. example, one large study' examined maxillofacial

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention trauma in patients registered in the Department of

Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Innsbruck,

Austria, from 1991 and 2000. Of the 9,543 patients seen

For author disclosure of financial relationships and mention of

unlabeled use of drugs, see the next page. during that time for maxillofacial trauma, 2,991 (31%)

of those injuries were sports related. Dentoalveolar

continued

THE PHYSICIAN AND SPOATSMEDICINE e Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 23

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

trauma occurred in 51% of all maxillofacial trauma, odontalligaments and is covered by cementum. The

and 56% of the dentoalveolar injuries were compli- root houses the vascular pulp, which furnishes the

cated by associated injuries.' Such data are useful in blood and nerve supply for the tooth. The crown is

predicting the prevalence of dental trauma in collision made up of a tough outer shell of enamel that protects

or contact sports, such as skiing, soccer, cycling, an inner layer of dentin and the portion of the pulp

mountain biking, ice hockey, and ball sports, among that extends into crown. The border at which the

many others. crown meets the root is known as the cementoenamel

junction.' The gingival tissue overlies the mandible

Basic Dental Anatomy and maxilla and seals the tooth in the socket.

Teeth are housed within maxillary and mandibular

alveolar bone (figure 1), which contains individual Common Dental Injuries

sockets for each tooth. Each tooth consists of a root Dental injuries include fractures, luxation, avulsion,

and crown. The root attaches to the socket via peri- socket fracture, and associated trauma (eg, lip and

mucosal lacerations, maxillary or mandibular frac-

tures, temporomandibular joint damage, and concus-

Figures 1, 3: Medical Art Services, Inc. sion). Physicians must recognize each injury type to

provide proper initial treatment and refer more seri-

ously injured patients to the emergency department,

team dentist, or other dental professional.

Fractures. Tooth fractures disrupt the enamel or

cementum and may involve dentin or pulp. They are

typically caused by a direct blow to the tooth or by an

indirect blow transmitted through the jaw.' Fractures

can affect the root, crown, or both, producing a wide

range of severity. Fractures can be as simple as a

chipped tooth, which only involves the enamel, as well

as the other extreme, a vertical fracture, which cleaves

the tooth from the crown through the root, involving

enamel, dentin, and pulp along the fissure. When the

pulp is involved, the injury is usually very painful and is

frequently identified as a bleeding site or a pinkish dot

in the center of the dentin (figure 2) ."·'" Treatment and

return to play varies with the severity of the fracture.

Crown fractures are commonly classified into one

of four types (figure 3):

• Type 1 is an enamel only or "chip fracture";

• Type 2 is a fracture through enamel and dentin;

FIGURE 1. Anatomy of a normal tooth shows its position in the • Type 3 involves the enamel, dentin, and pulp; and

jaw. All teeth have an enamel crown that covers the dentin and • Type 4 fractures involve the root.

pulp cavity. The gingival tissue seals the tooth into its socket. The closer a root fracture is to the cementoenamel

Dr Honsik is astaff physician in the department of family practice and on the Fontana, CA 92335; e-mail to kenneth.a.honsik@kp.org.

faculty of the Sports Medicine Fellowship program at Kaiser Permanente in Disclosure information: Dr Honsik discloses no significant relationship

Fontana. California. with any manufacturer of any commercial product mentioned in this article.

Address correspondence to: Kenneth A. Honsik, MD, 9985 Sierra Ave. No drug is mentioned in this article for an unlabeled use.

24 Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 e THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

Figures 2,4,5: Courtesy of Marf< Roettger, DDS

FIGURE 2. A fracture can be as simple as a chip in the enamel or FIGURE 3. Type 1, type 2, and type 3 fractures involve the tooth

as serious as involving the pulp chamber (arrow). crown. Type 4 fractures involve the root and require immediate

care by a dentist.

junction, the more unstable it is and the poorer the by bone and the tooth will be lost.

prognosis.' Dental injuries that involve the root and The need for endodontic (root canal) therapy fol-

pulp are considered more severe and require immedi- lowing the proper reirnplantation of an avulsed tooth

ate professional attention. is determined by the maturity of the root at the time of

Luxation. Luxation is the displacement of the tooth injury. A mature root has a closed apex, and this makes

from its normal position (figure 4). Teeth may become revascularization of the dental pulp impossible and

laterally luxated, extruded, or intruded. A laterally lux- always requires endodontic therapy. An immature root

ated tooth will be displaced anterior or posterior to the has an open apex and allows for a chance of revascu-

adjacent teeth. If the tooth is extruded, it will appear larization following reirnplantation, possibly avoiding

longer than the other teeth in the arch (partial avul- endodontic therapy. Only permanent teeth should be

sion). In cases of intrusion, the tooth will be shorter reirnplanted. Primary or "baby teeth" should never be

than its neighboring row and should not be reposi- reirnplanted. n•

tioned on site. Intrusion typically involves disruption Associated injuries. All of the previously described

of the alveolar socket and periodontal ligaments.'·" injuries can be associated with other types of maxillo-

Loose teeth are considered tooth subluxations without facial trauma. In the previously noted study 2 from Aus-

significant displacement or alveolar bone disruption. tria, 56% of dentoalveolar injuries were complicated by

However, in some cases, a "loose tooth" may be the other injuries. Associated maxillofacial injuries can be

result of a transverse root or cementoenamel junction as simple as a gum or lip laceration to as serious as a

fracture. Radiographs are recommended for all concussion, temporomandibular joint damage, or

trauma-induced loose teeth. facial or alveolar bone fracture. The examiner should

Avulsion. Tooth avulsion is a total separation of the always look for these injuries when evaluating an

tooth from the socket (figure 5). This injury involves active patient for dentoalveolar trauma. lip or mouth

complete rupture of the periodontal ligaments. As lacerations should be radiographed before closure to

such, the time from injury to reimplantation of the rule out embedded tooth or bone fragments when

tooth is critical to its survival. Vitality of the periodontal these injuries are associated with a tooth fracture.'

ligament (PDL) cells on the root surface of an avulsed

tooth will determine whether the PDL will regenerate Patient Examination

or if the root will ankylose to the bone. If ankylosis Because of the high velocity forces involved in den-

occurs, the root of the tooth will ultimately be replaced toalveolar trauma, the provider should always begin

continued

THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE e Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 25

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

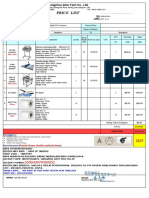

Crown Injury {Type 1-2) Lateral Luxation

Exam Findings Exam Findings

Exposed dentin has yellow hue; presence of pink dot or Tooth may look out of place or feel loose; athlete may complain

bleeding in center of tooth signals pulp involvement; pain of problem with bite; palpation of the alveolar socket may reveal

may occur with or without sensitivity to cold water and air deformity or fracture

Emergency Care Emergency Care

• Recover fragments • Determine the number of teeth affected and the stability of the row

• Handle only by enamel surface • Gently reposition tooth or teeth into original position with a dry,

• Control bleeding gloved handt

• Rinse tooth gently with sterile saline or clean water, if soiled • If repositioning is too painful or not attainable, refer patient

• Transport fragments in saline soaked sterile gauze to a dental professional at once

Treatment • If repositioning is successful, athletes should follow a strict

• Patient may be referred to dentist within 48 hr if only soft food and liquid diet that avoids excessive biting and chewing

enamel or dentin is involved • Consider splinting

• Reconstruction of tooth or fillings Treatment

Return-to-Play Guidelines • If the tooth was significantly displaced, alveolar fracture is

May return immediately if bleeding is controlled and athlete highly probable, and athlete should seek immediate dental care

has a properly fitting mouth guard; patient should have a • If the tooth was minimally displaced or loose, the patient

dental consultation within 48 hr should seek dental consult within 1 day

• Radiographs are usually done

Crown Injury {Type 3) • Endodontic therapy (root canal) possible

Exam Findings Return-to-Play Guidelines

More commonly have severe pain If athlete has a custom mouth guard, immediate return to play

Emergency Care may be considered;* return to play is not recommended for

May place a drop of medical grade cyanoacrylate on exposed athletes without custom mouth guards or if severe alveolar

pulp to decrease risk of infection and reduce pain of exposed nerve injury is suspected. Return to play after dental consult depends

Treatment on recommendations of the team dentist.

• Refer to dentist within 3 hr; pulpitis may arise from bacterial

contamination of sterile pulp space

• Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended; tetanus booster if Extruded Luxation

needed

Exam Findings

• Root canal therapy is done by dental professional Tooth appears longer than adjacent teeth; palpate the entire tooth

Return-to-Play Guidelines row and alveolar sockets; injury may or may not be painful and

Immediate return to play is not recommended;* eventual return to disrupts blood and nerve supply at insertion of root

play determined by dental provider Emergency Care

• Instruct patient to bite down on gauze or mouth guard to

Root Injury {Type 4) assist repositioning the tooth in the sockett

Exam Findings Treatment

Tooth may or may not be loose; can be painless, very painful, • Dental consult within 24 hr of injury if teeth have been

or numb repositioned or immediately if acceptable alignment is not

Emergency Care achieved

• Tooth should be secured to adjacent teeth in row with an • Obtain x-rays to detect possible fracture

improvised splint, such as a mouth guard, dental wire, or • The tooth will require splinting, and endodontic or root

sugar-free gum canal therapy may be needed

Treatment Return-to-Play Guidelines

• All suspected root fractures require x-rays Return to play is not recommended for athletes without

• Patient should seek dental consult immediately after injury custom mouth guards; return to play after dental consult

Return-to-Play Guidelines depends on recommendations of the dental professional.

Immediate return to play is not recommended;* eventual Athletes with custom mouth guards may consider immediate

return to play determined by dental provider return to play if tooth is acceptably repositioned.*

• Adult athletes (> 18 years old) may make an informed decision on return to play, as long as they understand the risks and potential complications.

t Sideline providers with experience in administering dental anesthesia may consider doing so before manipulating teeth.

TMJ =temporomandibular joint

26 Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 e THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

Intruded Luxation Alveolar Fracture

Exam Findings Exam Findings

Severe pain likely; tooth appears shorter than adjacent teeth Pain likely present; detected with careful palpation of sockets

in row; typically involves severe injury to alveolar socket, and gum line

periodontal ligaments, and underlying marrow Emergency Care

Emergency Care • If fracture is suspected, do not replace avulsed tooth

• Do not reposition on field • Do not attempt to reduce displaced alveolar fragments

• May be associated with significant alveolar fracture on the field

Treatment Treatment

• Immediate consultation with dental professional •Refer to a dentist immediately

• Tooth may re-erupt or be guided back into place with Return-to-Play Guidelines

orthodontic care Immediate return to play is not recommended;* eventual

Return-to-Play Guidelines return is determined by dental provider

• Immediate return to play is not recommended;* eventual

return to play is determined by dental provider

• Root canal therapy possible

Other Injuries (Lacerations, concussion, facial bone fractures,

and TMJ trauma)

Avulsion Exam Findings

Bleeding, facial asymmetry, abnormal extraocular eye

Exam Findings movement, abnormal bite alignment, altered mental status

Tooth knocked out of socket; associated pain

Emergency Care

Emergency Care • Control bleeding with pressure

• Find the missing tooth • Stabilize suspected fractures and transport patient to

• Control bleeding emergency department

• Rinse tooth with sterile or clean water • Follow standard concussion guidelines

• Do not scrub tooth or handle by the root

• Primary goal is to replace the tooth immediately if alveolar Treatment

socket fracture is not present • Lacerations may be repaired if no obvious displaced tooth

• Do not replace primary ("baby") teeth fragments are present

• Press tooth firmly back into socket, but make certain that • Delay repair if tooth fragments might be embedded in oral

the tooth is correctly positioned mucosa

• Ensure proper positioning; provider should feel palpable • X-ray injury to detect any fragments

click when tooth is properly seated Return-to-Play Guidelines

• If successful on-field implantation occurs, the tooth must Fractures and severe concussions take priority over dental

be temporarily splinted to the adjacent stable teeth trauma and require immediate transport to an emergency

• Splints may be improvised (eg, mouth guards, sugar-free gum) department

Treatment

• Requires immediate dental consultation;

• If on-field rei mplantation is unsuccessful, transport the

athlete and tooth to a qualified provider or dentist for

rei mplantation within 30 min to 2 hr; after 2 hr tooth has

low likelihood of survival or successful rei mplantation

Return-to-Play Guidelines

Immediate return to play not recommended;* eventual

return to be determined by the dental provider

THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE e Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 27

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

FIGURE 4. A laterally displaced tooth (luxation). Extruded and FIGURE 5. The site of an avulsed tooth. An avulsed tooth should

laterally displaced teeth should be returned to their proper position be re implanted within 30 minutes to 2 hours. Implantation after

if possible, but intruded teeth should not be repositioned on site. 2 hours greatly decreases the chance for tooth survival.

the exam with the ABCs of trauma (airway, breathing. Currently, three types of mouth guards are available

circulation, and consciousness/alertness). It is ex- to athletes: stock, mouth-formed ("boil-and-bite"},

tremely important to determine alertness because of and custom-fabricated (figure 6; also see the Patient

increased risk of tooth fragment aspiration in con- Adviser, "Steps to Take for Dental Injuries," page 35).

cussed or unconscious athlete. Using a light source, The stock mouth guard comes in set sizes and is the

physicians should visually inspect the entire mouth least protective type. They are commonly trimmed

and maxillofacial region. The athlete's mouth may need down by the athletes for comfort and held in place by

to be rinsed for proper inspection. When doing this, use the bite force of the athlete. Boil-and-bite mouth

clean water for rinsing, and do not discard the rinse guards are the most commonly worn and marketed

immediately to allow inspection for tooth fragments or types but provide only mediocre protection. The boil-

teeth before disposal! If a fracture or avulsion is seen on and-bite mouth guard loses much of its protective

examination and the fragment or missing tooth is not properties during the form-fitting process. An overall

visible within the mouth, the athlete's clothes and site thickness of 3 mm is required for adequate cushion

of injury should be searched immediately. and absorption. Many times the athlete will bite too far

After completing the visual inspection, the provider through the mouth guard during the forming process,

should then palpate all teeth in both arches with a reducing the cushion between the teeth. Also through-

sterile, gloved hand, checking for asymmetry, loose- out the season, athletes will chew through portions of

ness, or mandibular and maxillary deformities. Exami- the mouth guard, further reducing the cushion and

nation procedures, treatment recommendations, and rendering it ineffective.'' Custom mouth guards are

return-to-play guidelines depend on the type of injury recommended by sports physicians and dental profes-

incurred (table 1).'""" sionals. They are significantly more expensive than

over-the-counter types but have been proven to pro-

Preventing Dentoalveolar Injury vide superior protection."·"

The American Dental Association recommends use Custom mouth guards are made by a dentist for an

of mouth guards for participation in football, gymnas- exact fit and are fashioned from a mold or cast of the

tics, basketball, boxing, field hockey, handball, ice patient's mouth. Custom mouth guards may be pro-

hockey, lacrosse, skateboarding, skiing, skydiving, duced by either a vacuum or pressure-lamination pro-

soccer, martial arts, racquetball, squash, roller hockey, cess. The pressure laminate variety is felt to be slightly

rugby, volleyball, water polo, weightlifting, and superior to the vacuum form, because the multiple lay-

wrestling. Mouth guard use has been shown to ers ensure adequate thickness of the device. These

decrease the frequency and severity of dental injuries.' 11 mouth guards may also be further customized by mak-

28 Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 e THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMIDICINE

PRACTICE

ESSENTIALS

Dentaoalveolar trauma

continued

Figures 6 A, B: staff photos; Figures 6 C, 0: Courtesy of Ray Pad ilia, DOS

FIGURE 6. Three basic types of mouth guards are available. Stock (not shown), mouth-formed {"boil-and-bite," A, B), and custom (C,D)

mouth guards provide different levels of protection. Custom mouth guards are expensive, but their form lit provides the greatest protection.

Mouth-formed types are relatively easy to produce, but they may be chewed through and lose their protective qualities.

ing them in the school or team colors (figure 6D}. Much be familiar and comfortable with basic diagnosis and

discussion has centered on the question of whether emergency care for dental injuries. Care for more seri-

mouth guards aid in preventing concussions. To date, ous injuries should be supplied by team dentists or

there is no evidence that mouth guard use decreases other dental providers. If treated correctly on the field,

the incidence of concussion among athletes. 10•13 injured patients can avoid complications such as poor

cosmesis, infection, and extensive dental reconstruc-

Putting the Bite on Dental Injury tion. Use of a properly fitted mouth guard is effective

Dental injuries are very common in most contact in preventing dental injury; with custom types provid-

and collision sports. Sports medicine providers should ing the best protection. '"·' 2 PSM

REFERENCES Am Fam Physician 2003;67(3) :511-516

l. Promoting oral health: interventions for preventing dental 8. International Association of Dental Traumatology: Treat-

caries, oral and pharyngeal cancers, and sports-related ment Guidelines. Available at http://www.iadt-dental-

craniofacial injuries: a report on recommendations of the trauma.org/Trauma/ dental_trauma.htm. Accessed June

Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR. 24,2004

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50(RR 21): 1-13 9. Sports Dentistry Online: Sports dentistry facts. Available at

2. Thli T, Hachl 0. Hohlrieder M, et al: Dentofacial trauma in http://www.sportsdentistry.com/facts.htrnl. Accessed June

sports accidents. Gen Dent 2002;50(3):274-279 24,2004

3. Wisniewski JF: Chapter 60: Dental injuries, in: Safran MR, 10. Labella CR, Smith BW, Sigurdsson A: Effect of mouthguards

McKeag DB, Van Camp SP (eds): Manual of Sports Medi- on dental injuries and concussions in college basketball.

cine. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998, pp 500-505 Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34(1):41-44

4. Honsik K: Dental injuries, in Rubin A: Sports Injuries and 11. Sports Dentistry Online: Types of athletic mouthguards.

Emergencies: A Quick Response Manual. New York City, Available at www.sportsdentistry.com/mouthguards.htrnl.

McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 54-59 Accessed June 24, 2004

5. Roberts WO: Field care of the injured tooth. Phys Sports- 12. Newsome PR, Iran DC, Cooke MS: The role of the mouth-

med 2000;28(1):101-102 guard in the prevention of sports-related dental injuries: a

6. Dale RA: Dentoalveolar trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am review. Int J Paediatr Dent 200 1; 11(6):396-404

2000;18(3):521-538 13. McCrory P: Do mouthguards prevent concussions? Br J

7. Douglass AB, Douglass JM: Common dental emergencies. Sports Med 2000;35(2):81-82

THE PHYSICIAN AND SPORTSMEDICINE e Vol 32 • No. 9 • September 2004 29

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5808)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- History of TandoorDocument3 pagesHistory of Tandoorpiyush100% (2)

- SsangYong Actyon Sports Q149 2011.01 Electrical Wiring DiagramDocument84 pagesSsangYong Actyon Sports Q149 2011.01 Electrical Wiring Diagramcelyoz100% (1)

- Top 25 Food Ideas For Baby Led Weaning: VegetablesDocument1 pageTop 25 Food Ideas For Baby Led Weaning: Vegetablesbecca wiseNo ratings yet

- Reading Questions - Science and BeautyDocument3 pagesReading Questions - Science and BeautyEllen Lam100% (1)

- Price List: With StandDocument1 pagePrice List: With StandAlex TajoNo ratings yet

- The Waves of The Technological InnovationsDocument17 pagesThe Waves of The Technological InnovationsRio AwitinNo ratings yet

- XH260L - XH260V: Dixell Operating InstructionsDocument4 pagesXH260L - XH260V: Dixell Operating InstructionsJennifer Eszter SárközyNo ratings yet

- Download full chapter The First Institutional Spheres In Human Societies Evolutionary Analysis In The Social Sciences 1St Edition Abrutyn pdf docxDocument54 pagesDownload full chapter The First Institutional Spheres In Human Societies Evolutionary Analysis In The Social Sciences 1St Edition Abrutyn pdf docxmarcus.stassinos948No ratings yet

- Use of Stainless Steel CrownsDocument16 pagesUse of Stainless Steel CrownsKaren De la GarzaNo ratings yet

- H BridgeDocument41 pagesH BridgeSheikh IsmailNo ratings yet

- HDES-D0165 General Tolerance in Dimension (Eng)Document1 pageHDES-D0165 General Tolerance in Dimension (Eng)juniorferrari06No ratings yet

- Gear Hobbing Shaping and Shaving A Guide To Cycle Time Estimating and Process Planning PDFDocument183 pagesGear Hobbing Shaping and Shaving A Guide To Cycle Time Estimating and Process Planning PDFvenkat100% (2)

- Vision Document (Template)Document5 pagesVision Document (Template)Andrew MacAulayNo ratings yet

- E SHB 2009 - Vav3Document169 pagesE SHB 2009 - Vav3ictgisNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Finance Project On WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENTDocument82 pagesSummer Training Finance Project On WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENTPravin chavda100% (2)

- Apxv9r20b C A20 PDFDocument2 pagesApxv9r20b C A20 PDFКонстантин ПетровNo ratings yet

- 8902 LS (Parker)Document20 pages8902 LS (Parker)abdohalim248No ratings yet

- Carbohydrates: MonosaccharidesDocument8 pagesCarbohydrates: MonosaccharidesLily NemphisNo ratings yet

- Non-Mendelian InheritanceDocument12 pagesNon-Mendelian InheritanceBillones Rebalde MarnelleNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS B Inggris 5Document8 pagesSoal PTS B Inggris 5Hasna NurlailiNo ratings yet

- Teens 2 - Resource PackDocument14 pagesTeens 2 - Resource PackGigliane SouzaNo ratings yet

- ArthritisDocument5 pagesArthritismeenuNo ratings yet

- Microprocessor 4th SemDocument316 pagesMicroprocessor 4th SemDaggupatiHarishNo ratings yet

- Critical ResultDocument2 pagesCritical ResultSUSANTONo ratings yet

- Pasler Dufourt PNM2011Document34 pagesPasler Dufourt PNM2011balintkNo ratings yet

- Kode Icd 10Document38 pagesKode Icd 10interna squardNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Biopotential Measurement and Excitation: (Bioelectromagnetism - Jakko Malmivuo, Robert Plonsey)Document23 pagesIntroduction To Biopotential Measurement and Excitation: (Bioelectromagnetism - Jakko Malmivuo, Robert Plonsey)Lynn WankharNo ratings yet

- Redox Reactions: Neet /jee QuestionsDocument27 pagesRedox Reactions: Neet /jee QuestionsAsher LaurierNo ratings yet

- Kothari Sugar Factory Internshipproject SamoleDocument52 pagesKothari Sugar Factory Internshipproject Samolenoobwarrior3No ratings yet

- Identification Tables For Common Minerals in Thin SectionDocument4 pagesIdentification Tables For Common Minerals in Thin SectionTanmay KeluskarNo ratings yet