Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mackenzie Bricolage e Performatividade

Uploaded by

AndréGuilhermeMoreiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mackenzie Bricolage e Performatividade

Uploaded by

AndréGuilhermeMoreiraCopyright:

Available Formats

An Equation and Its Worlds: Bricolage, Exemplars, Disunity and Performativity in Financial

Economics

Author(s): Donald MacKenzie

Source: Social Studies of Science, Vol. 33, No. 6 (Dec., 2003), pp. 831-868

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3182986 .

Accessed: 28/06/2014 07:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Studies of

Science.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Sss

ABSTRACT Thispaperdescribesand analysesthe history of the fundamental

equationof modernfinancialeconomics:the Black-Scholes (or Black-Scholes-Merton)

optionpricingequation.Inthathistory, severalthemesof potentially general

importance are revealed.First,

the keymathematical workwas not rule-following but

bricolage,creativetinkering.Second,itwas, however,bricolageguided bythe goal

of findinga solutionto the problemof optionpricinganalogousto existing

exemplary solutions,notablythe CapitalAssetPricingModel,whichhad successfully

been appliedto stockprices.Third,the centralstrandsof workon optionpricing,

althoughall recognizably 'orthodox'economics,were not unitary. Therewas

significant

theoreticaldisagreement amongstthe pioneersof optionpricingtheory;

thisdisagreement, turnsout to be a strength

paradoxically, of the theory.Fourth,

optionpricingtheoryhas been performative. Ratherthansimplydescribing a pre-

italteredthe world,in generalin a waythatmade

existingempiricalstateof affairs,

itselfmoretrue.

Keywords Black-Scholes,

bricolage,optionpricing, socialstudiesof

performativity,

finance

An Equation and its Worlds:

Bricolage,Exemplars,Disunityand

in FinancialEconomics

Performativity

Donald MacKenzie

Economics and economiesare becominga majorfocusforsocial studiesof

science. Historiansof economics such as Philip Mirowskiand the small

number of sociologists of economics such as Yuval Yonay have been

applyingideas fromscience studieswithincreasingfrequencyin the last

decade or so.' Establishedscience-studiesscholarssuch as Knorr Cetina

and newcomersto thefieldsuch as Izquierdo,Lepinay,Millo and Muniesa

have begun detailed, oftenethnographic,work on economic processes,

with a particular focus on financial markets.2Actor-networktheorist

Michel Callon has conjoinedthe two concernsby arguingthatan intrinsic

linkexistsbetweenstudiesofeconomicsand ofeconomies.The economyis

not an independentobject thateconomicsobserves,arguesCallon (1998).

Rather,the economy is performedby economic practices.Accountancy

and marketingare among the more obvious such practices,but, claims

Callon, economics in the academic sense plays a vitalrole in constituting

and shapingmoderneconomies.

Social StudiesofScience33/6(December 2003) 831-868

?) SSS and SAGE Publications(London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi)

[0306-3127(2003 12)33:6;83 1-868;039200]

www.sagepublications.com

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

832 Social Studies of Science 33/6

This paper contributesto the emergentscience-studiesliteratureon

economics and economies by way of a historicalcase study of optiont

pricingtheory(termsmarkedt are definedin the glossaryinTable 1). The

theoryis a 'crownjewel' of moderneconomics:'when judged by its ability

to explainthe empiricaldata, optionpricingtheoryis the most successful

theorynot onlyin finance,but in all ofeconomics' (Ross, 1987: 332). Over

thelastthreedecades, optiontheoryhas become a vitallyimportantpartof

financialpractice.As recentlyas 1970, the marketin derivativest such as

options was tiny; indeed, many modern derivativeswere illegal. By

December 2002, derivativescontractstotalingUS$165.6 trillionwere

outstandingworldwide,a sum equivalentto around US$27,000 forevery

human being on earth.3Because of its centrality to thishuge market,the

equationthatis myfocushere,the Black-Scholesoptionpricingequation,

may be 'the most widelyused formula,with embedded probabilities,in

human history'(Rubinstein,1994: 772).

The developmentof option pricingtheoryis part of a largertrans-

formationof academic finance.Untilthe 1960s, the studyof financewas a

marginal,low statusactivity:largelydescriptivein nature,taughtin busi-

ness schools not in economics departments,and with only weak in-

tellectuallinkagesto economic theory.Since the 1960s, financehas be-

come analytical, theoretical and highly quantitative.Although most

academicfinancetheorists'postsare stillin businessschools,muchofwhat

theyteach is now unequivocallypartof economics.Five financetheorists-

includingtwo of the centralfiguresdiscussedhere,RobertC. Merton and

MyronScholes - have won Nobel prizesin economics.

This intellectualtransformation was interwoven withthe rapid expan-

sion of businessschools in the US. In the mid-1950s,US businessschools

were producing around 3000 MBAs annually.By the late 1990s, that

figurehad risen to over 100,000 (Skapiner,2002). As business schools

grew,theyalso became more professionaland 'academic', especiallyafter

the influentialFord Foundationreport,HigherEducationforBusiness(Gor-

don and Howell, 1959). At the same time,the importanceof the finance

sectorin theUS economygrewdramatically, and increasingproportionsof

financialassets wereheld not directlyby individualsbut by organizations

such as mutual fundsand pension funds.These organizationsformeda

readyjob marketforthe growingcohortsof studentstrainedin finance.

The transformation oftheacademic studyoffinanceis the subjectof a

finehistoryby Bernstein(1992), and the interactionsbetweenthistrans-

formation,the evolutionof US business schools, and changingcapital

marketshave been analysed ably by Whitley(1986a, 1986b). However,

whatthe existingliterature has not done fullyis to 'open the black box' of

mathematicalfinancetheory. That - at leastforthetheoryofoptionpricing

- is thispaper's goal.4

Limitationof space means that the focus of this paper is on the

mathematicsof option pricingtheoryand on its intellectualcontext.The

interactionbetweentheoryand practice- the processesof the adoptionby

practitionersofoptionpricingtheory,and theconsequencesofitsadoption

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 833

- is the subject of a 'sister'paper (MacKenzie and Millo, forthcoming),

althoughthe issue of performativity means thatthe subject-matter of that

paper willbe revisitedbrieflybelow.

In thisarticle,fourthemeswill emerge.I would not describethemas

'findings',because of the limitationson whatcan be inferredfroma single

historicalcase-study,but theymay be of general significance.The first

themeis bricolage.Creativescientific practiceis typicallynot thefollowing

of set rules of method:it is 'particularcourses of action withmaterialsat

TABLE I

Terminology

Arbitrage; arbitrageur Tradingthatseeks to profitfromprice discrepancies;a trader

who seeks to do so.

Call See option.

Derivative An asset,such as a future or option, the value of whichde-

pends on the price of another,'underlying',asset.

Discount To calculatethe amountby whichfuturepaymentsmustbe

reducedto givetheirpresentvalue.

Expiration See option.

Future A contracttradedas an organizedexchangein whichone party

undertakesto buy,and the otherto sell, a set quantityof an

asset at a set price on a givenfuturedate.

Implied volatility The volatilityof a stockor index consistentwiththe price of

options on the stockor index.

Log-normal A variableis log-normally

distributedifitsnaturallogarithm

followsa normaldistribution.

Market maker In the optionsmarket,a marketparticipantwho tradeson his/

her own account,is obligedcontinuouslyto quote pricesat

whichhe/shewill buy and sell options,and is not permittedto

executecustomerorders.

Option A contractthatgivesthe right,but not obligation,to buy ('call')

or sell ('put') an asset at a givenprice (the 'strikeprice') on, or

up to, a givenfuturedate (the 'expiration').

Put See option.

Riskless rate The rateof interestpaid by a lenderwho creditorsare certain

will not default.

Short selling The sale of a securityone does not own, e.g. by borrowingit,

sellingit, and laterrepurchasingand returning it.

Strike price See option.

Swap A contractto exchangetwo income streams,e.g. fixed-rate

and

intereston the same notionalprincipalsum.

floating-rate

Volatility The extentof the fluctuationsof the price of an asset, conven-

tionallymeasuredby the annualizedstandarddeviationof con-

tinuously-compounded returnson the asset.

Warrant A call option issued by a corporationon its own stock.Its

exercisetypicallyleads to the creationof new stocksratherthan

the transferof ownershipof existingstock.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

834 Social Studies of Science 33/6

hand' (Lynch, 1985: 5). Whilethishas been documentedin overwhelming

detail by ethnographicstudiesof laboratoryscience, this case-studysug-

gests it may also be the case in a deductive, mathematicalscience.

Economists- at least the particulareconomistsfocusedon here- are also

bricoleurs.5

They are not, however,random bricoleurs,and the role of existing

exemplarysolutionsis the second issue to emerge.Ultimately,of course,

this is a Kuhnian theme. As is well known,at least two quite distinct

meaningsof the keyterm'paradigm'can be foundin Kuhn's work.One -

by farthe dominantone in how Kuhn's workwas takenup by others- is

the 'entireconstellationof beliefs,values,techniques,and so on sharedby

the membersof a given [scientific]community'(Kuhn, 1970: 175). The

second - rightly describedby Kuhn as 'philosophically... deeper' - is the

exemplar,the problem-solution thatis accepted as successfuland thatis

creatively drawn upon to solve furtherproblems (Kuhn, 1970: 175; see

also Barnes, 1982).

The role of the exemplarwill become apparenthere in the contrast

between the work of Black and Scholes and that of mathematicianand

arbitrageurtEdward 0. Thorp. Amongst those who worked on option

pricingprior to Black and Scholes, Thorp's work is closest to theirs.

However,whileThorp was seekingmarketinefficiencies to exploit,Black

and Scholes were seeking a solution to the problem of option pricing

analogous to an existingexemplarysolution,the Capital Asset Pricing

Model. This was not justa generalinspiration:in his detailedmathematical

work,Black drewdirectlyon a previousmathematicalanalysison whichhe

had worked with the Capital Asset Pricing Model's co-developer,Jack

Treynor.

As PeterGalison and othershave pointedout, the keyshortcomingin

the view of the 'paradigm' as 'constellationof beliefs,values, techniques,

and so on' is thatit overstatesthe unityand coherenceof scientificfields

(Galison, 1997; Galison and Stump, 1996). Nowhere is this more true

than when outsidersdiscuss 'orthodox' neoclassical economics, and the

nature of economic orthodoxyis the thirdtheme exploredhere. Black,

Scholes, Merton,severalof theirpredecessors,and most of those who in

the 1970s subsequentlyworked on option pricingwere all (with some

provisosin the case of Black, to be discussedbelow) recognizably'ortho-

dox' economists.As others studyingdifferent areas of economics have

found, however,orthodoxyseems not to be a single unitarydoctrine,

substantiveor methodological(see Mirowskiand Hands, 1998;Yonay and

Breslau, 2001). For example, Robert C. Merton, the economistwhose

name is most closelyyokedto those of Black and Scholes, did not accept

the originalversionof the Capital AssetPricingModel, the apparentpivot

of theirderivation,and Merton reached the Black-Scholes equation by

drawingon different intellectualresources.Black, in turn,never found

Merton's derivationentirelycompelling,and continuedto champion the

derivationbased on theCapital AssetPricingModel. So no entirely unitary

'constellationof beliefs,values, techniques,and so on' can be found.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 835

Economic 'orthodoxy'is a reality- attendconferencesof economistswho

feelexcluded by it, and one is leftin no doubt on that- but it is a reality

that should perhaps be construedas a clusterof familyresemblances,a

clusterthatarisesfromimaginativebricolagedrawingon an onlypartially

overlappingset of existingexemplarysolutions.'Orthodox' economics is

an 'epistemicculture'(Knorr Cetina, 1999), not a catechism.

A major aspect of Galison's critiqueof the Kuhnian paradigm (con-

ceived as all-embracing'constellation')is his argumentthat diversityis a

sourceofrobustness,not a weakness.Though Galison's topicis physics,his

conclusion also appears to hold true of economics. Philip Mirowskiand

Wade Hands, describingthe emergenceofmoderneconomicorthodoxyin

the postwarUS, put the point as follows:

Ratherthansayingit [neoclassicism]simplychased out the competition-

whichit did, ifby 'competition'one means the institutionalists,

Marxists,

and Austrians- and replaced diversity witha singlemonolithichomoge-

neous neoclassical strain,we say it transformeditselfinto a more robust

ensemble.Neoclassical demand theorygained hegemonyby going from

patches of monoculturein the interwarperiod to an interlockingcom-

petitiveecosystemafterWorldWar II. Ratherthan presentingitselfas a

single,brittle,theoreticalstrand,neoclassicismoffereda more flexible,

and thusresilientskein. (Mirowskiand Hands, 1998: 289; see also Sent,

forthcoming)

As we shall see, that general characterizationappears to hold for the

particularcase of optionpricingtheory.

The final theme explored here, and in the sisterpaper referredto

above (MacKenzie and Millo, forthcoming), is performativity.As we shall

see, thereis at least qualifiedsupporthereforCallon's conjecture,albeitin

a case thatis favourableto the conjecture,since optionpricingtheorywas

chosen for examinationin part because it seemed a plausible case of

performativity. Optionpricingtheoryseems to have been performative in a

strongsense: it did not simplydescribe a pre-existing world,but helped

createa worldof whichthe theorywas a truerreflection.

It is of course not surprisingthata social science like financetheory

has thepotentialto alteritsobjectsof study:themoredifficult issue,which

fortunately does not need to be breachedhere,is to specifyaccuratelythe

non-trivialways in whichnaturalsciences are performative (see Hacking,

1992a, and froma different viewpoint,Bloor, 2003). That a social science

likepsychology, forexample,has a 'necessarilyreflexive

character'and that

psychologistsinfluenceas well as describe'the psychologicallives of their

host societies'has been arguedby Richards(1997: xii), and Ian Hacking's

work(such as Hacking, 1992b and 1995a) also demonstratesthepoint.As

I have argued elsewhere(MacKenzie, 2001), financeis a domain of what

Barnes (1983) calls 'social-kind' terms or what Hacking (1995b) calls

'human kinds', with theirtwo-way'looping effects'between knowledge

and its objects.

It is clearlypossible in principle,in otherwords,forfinancetheoryto

be performative ratherthan simplydescriptive.However, that does not

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

836 Social Studies of Science 33/6

remove the need for empirical examination.That the theory can be

performative does not implythatit has been performative. Indeed, as we

shall see, the performativity of classic option pricingtheoryis incomplete

and historically specific- it did not make itselfwhollyor permanently true

- and exploringthe limitsand the contingencyof its performativity is of

some interest.

'Too Much on Finance!'

Optionsare old instruments, but untilthe 1970s age had notbroughtthem

respectability.Putst and callst on the stock of the Dutch East India

Company were being bought and sold in Amsterdamwhen de la Vega

discussed its stock marketin 1688 (de la Vega, 1957), and subsequently

optionswerewidelytradedin Paris,London, NewYorkand otherfinancial

centres.They frequentlycame under suspicion,however,as vehiclesfor

speculation.Because the cost of an option was typicallymuch less than

thatof the underlyingstock,a speculatorwho correctlyanticipatedprice

rises could profitconsiderablyby buyingcalls, or benefitfromfalls by

buyingputs,and such speculationwas oftenregardedas manipulativeand/

or destabilizing.Buying options was oftenseen simplyas gambling,as

bettingon stockprice movements.In Britain,optionswere banned from

1734 and again from1834, and in France from1806, althoughthesebans

were widelyflouted(Michie, 1999: 22, 49; Preda, 2001: 214). Several

American states,beginningwith Illinois in 1874, also outlawed options

(Kruizenga, 1956). Althoughthe main targetin the USA was optionson

agriculturalcommodities,options on securitieswere often banned as

well.

Options' dubious reputationdid not preventseriousinterestin them.

In 1877, forexample,the London brokerCharles Castelli,who had been

'repeatedlycalled upon to explainthevariousprocesses'involvedin buying

and sellingoptions,publisheda bookletexplainingthem,directedappar-

entlyat his fellowmarketprofessionalsratherthan popular investors.He

concentratedprimarily on theprofitsthatcould be made by thepurchaser,

and discussedonlyin passinghow optionswerepriced,notingthatprices

tended to rise in periods of what we would now call high volatility.t

His

booklet ended - in a nice correctiveforthose who believe the late 20th

century'sfinancialglobalizationto be a novelty- withan example of how

options had been used in bond arbitragetbetween the London Stock

Exchange and the ConstantinopleBourse to capturethe high contango6

rateprevailingin Constantinoplein 1874 (Castelli, 1877: 2, 7-8, 74-77).

Castelli's 'how to' guide employedonly simple arithmetic.Far more

sophisticatedmathematically was the thesissubmittedto the Sorbonnein

March 1900 byLouis Bachelier,a studentoftheleadingFrenchmathema-

tician and mathematicalphysicist,Henri Poincare. Bachelier sought 'to

establishthelaw ofprobabilityofpricechangesconsistentwiththemarket'

in Frenchbonds. He assumedthatthepriceofa bond, x, followedwhatwe

would now call a stochasticprocess in continuous time: in any time

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 837

interval,howevershort,the value of x changedprobabilistically.

Bachelier

constructedan integralequation thata continuous-timestochasticprocess

had to satisfy.

Denotingbyp, t dx theprobabilitythatthepriceof thebond

at timet would be betweenx and x + dx,Bacheliershowedthattheintegral

equation was satisfiedby:

H

p = H exp - (7TH2x2/t)

where H was a constant. (For the reader's convenience,notationused

throughoutthisarticleis gatheredtogetherinTable 2.) For a givenvalue of

t, the expressionreduces to the normal or Gaussian distribution,the

familiar'bell-shaped' curve of statisticaltheory.AlthoughBachelier had

not demonstratedthatthe expressionwas the onlysolutionof the integral

equation (and we now know it is not), he claimed that '[e]videntlythe

probabilityis governedby theGaussian law,alreadyfamousin the calculus

ofprobabilities'.He wenton to applythisstochasticprocessmodel- which

we would now call a 'Brownianmotion'because thesame processwas later

used by physicistsas a model of the path followedby a minuteparticle

subjectto randomcollisions- to variousproblemsin the determination of

the striketprice of options, the probabilityof their exercise and the

probabilityoftheirprofitability,

showinga reasonablefitbetweenpredicted

and observedvalues.7

When Bachelier'sworkwas 'rediscovered'by Anglo-Saxonauthorsin

the 1950s, it was regardedas a stunninganticipationboth of the modern

theoryof continuous-timestochasticprocesses and of late 20th-century

financetheory.For example,the translatorof his thesis,optiontheoristA.

JamesBoness, noted thatBachelier'smodel anticipatedEinstein'sstochas-

tic analysisof Brownianmotion (Bachelier, 1964: 77). Bachelier's con-

temporaries,however,wereless impressed.While modernaccounts of the

neglect of his work are overstated(Jovanovic,2003), the modesty of

Bachelier's career in mathematics- he was 57 beforehe achieved a full

TABLE2

Main Notation

(3 the covarianceof the price of an asset withthe generallevel of the market,dividedby

the varianceof the market

c striketprice of option

In naturallogarithm

N the (cumulative)normalor Gaussian distribution function

r risklesstrate of interest

a the volatilitytof the stockprice

t time

w warrantor optionprice

x stockprice

x* stockprice at expirationtof option

For itemsmarkedt see the glossaryin Table 1.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

838 Social Studies of Science 33/6

at Besancon ratherthanin Paris - seems due in part to his

professorship,

peers' doubts about his rigourand theirlack of interestin his subject

matter,the financialmarkets.'Too much on finance!' was the private

commenton Bachelier'sthesisby the leadingFrenchprobabilitytheorist,

Paul Levy (quoted in Courtaultet al., 2000: 346).

Option and Warrant Pricing in the 1950s and 1960s

The continuous-time randomwalk, or Brownianmotion,model of stock

marketprices became prominentin economics only fromthe late 1950s

onwards,and did so, furthermore, withan importanttechnicalmodifica-

tion, introducedto financeby Paul Samuelson, MIT's renownedmathe-

matical economist,and independentlyby statisticalastronomerM.F.M.

Osborne (1959). On Bachelier'smodel,therewas a non-zeroprobabilityof

prices becoming negative.When Samuelson, for example, learned of

Bachelier'smodel, 'I knewimmediatelythatcouldn't be rightforfinance

because it didn't respectlimitedliability'[Samuelson interview]:8 a stock

pricecould notbecome negative.So Samuelson and Osborne assumednot

Bachelier's 'arithmetic'Brownian motion, but a 'geometric' Brownian

motion,or log-normaltrandom walk, in whichprices could not become

negative.

In the late 1950s' and 1960s' US the random-walkmodel became a

key aspect of what became known as the 'efficientmarkethypothesis'

(Fama, 1970). Though it initiallystruckmanynon-academicpractitioners

as bizarreto posit thatstockprice movementswere random,the growing

number of financialeconomists argued that all today's informationis

alreadyincorporatedin today'sprices: ifit is knowablethatthe price of a

stock will rise tomorrow,it would alreadyhave risen today. Stock price

changesare influencedonlyby newinformation, which,by virtueof being

new, is unpredictableor 'random'.9 Like Bachelier, a number of these

financialeconomistssaw the possibilityof drawingon the random walk

model to studyoption pricing.Typically,theystudied not the prices of

optionsin generalbut thoseofwarrants.tOptionshad nearlybeen banned

in the US afterthe Great Crash of 1929 (Filer, 1959), and were traded

only in a small, illiquid, ad hoc marketbased in New York. Researchers

could in generalobtain onlybrokers'price quotationsfromthatmarket,

not the actual prices at which options were bought and sold, and the

absence of robustprice data made options unattractiveas an object of

study.Warrants,on the otherhand, weretradedin more liquid, organized

markets,particularly theAmericanExchange,and theirmarketpriceswere

available.

To Case Sprenkle,a graduatestudentin economicsatYale University

in the late 1950s, warrantprices were interestingbecause of what they

mightrevealabout investors'attitudesto and expectationsabout risklevels

(Sprenkle,1961). Let x* be thepriceof a stockon theexpirationt date of a

warrant.A warrantis a formof call option: it givesthe rightto purchase

the underlyingstock at strikeprice, c. At expiration,the warrantwill

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie:An Equation and its Worlds 839

be worthlessifx* is below c, since exercisingthe warrantwould

therefore

be more expensivethan simplybuyingthe stock on the market.If x* is

higherthan c, the warrantwill be worththe difference.So its value will

be:

0 ifx*<c

x* - c ifx*-c

Of course, the stockprice x* is not knownin advance, so to calculatethe

expectedvalue of the warrantat expirationSprenklehad to 'weight'these

final values by f(x*), the probabilitydistributionof x*. He used the

standardintegralformulaforthe expectedvalue of a continuousrandom

variable, obtainingthe followingexpressionfor the warrant'sexpected

value at expiration:

J

c

(x*- c) f(x*)dx*

To evaluatethisintegral,Sprenkleassumed thatf(x*) was log-normal(by

the late 1950s, that assumptionwas 'in the air', he recalls [Sprenkle

interview]),and that the value of x* expected by an investorwas the

currentstock price x multipliedby a constant,k. The above integral

expressionforthe warrant'sexpectedvalue thenbecame:

ln(kx/c)+ s212 ln(kx/c)- s2/2

kxN[ L L ] (1)

s s

whereln is the abbreviationfornaturallogarithm,s2 is the varianceof the

distributionof lnx*, and N is the (cumulative) Gaussian or normal

distribution function,thevalues ofwhichcould be foundin tablesused by

any statisticsundergraduate.'0

Sprenklethen argued that the expectedvalue of a warrantwould be

thepricean investorwould be preparedto pay forit onlyiftheinvestorwas

indifferent to risk or 'risk neutral'. (To get a sense of what this means,

imagine being offereda fair bet with a 50 percent chance of winning

$1,000 and a 50 percentchance of losing $1,000, and thus an expected

value of zero. If you would requireto be paid to takeon such a bet you are

'risk averse'; if you would pay to take it on you are 'risk seeking';if you

would takeit on withoutinducement,but withoutbeingpreparedto pay to

do so, you are 'riskneutral'.)Warrantsare riskierthantheunderlying stock

because of theirleverage- 'a givenpercentagechange in the price of the

stockwill resultin a largerpercentagechangein the price of the option' -

so an investor'sattitudeto risk could be conceptualized,Sprenklesug-

gested,as the price Pe he or she was preparedto pay forleverage.A risk-

seekinginvestorwould pay a positiveprice, and a risk-averseinvestora

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

840 Social Studies of Science 33/6

negativeone: thatis, a leveredassetwould have to offeran expectedrateof

return sufficientlyhigher than an unlevered one before a risk-averse

investorwould buy it. V the value of a warrantto an investorwas then

given,Sprenkleshowed,by:

ln(kxlc)+ s'12 ln(kxlc)- s'12

V= kxN[ () ] - (I - PI)cN nk /] (2)

s s

(The righthand side ofthisequationreducesto expression1 in thecase of

a riskneutralinvestorforwhom Pe= 0.) The values of k, s, and Pe were

posited by Sprenkleas specificto each investor,representing his or her

subjectiveexpectationsand attitudeto risk.Values of V would thus vary

between investors,and 'Actual prices of the warrantthen reflectthe

consensus of marginalinvestors'opinions - the marginalinvestors'ex-

pectationsand preferencesare the same as the market'sexpectationsand

preferences'(Sprenkle,1961: 199-201).

Sprenkleexaminedwarrantand stockpricesforthe 'classic boom and

bustperiod' of 1923-32 and fortherelativestabilityof 1953-59, hopingto

estimatefromthose prices 'the market'sexpectationsand preferences',in

other words the values of k, s, and Pe implied by warrantprices. His

econometricwork, however,hit considerable difficulties: 'it was found

impossibleto obtain these estimates'.Only by arbitrarily assumingk = 1

and testingout a range of arbitraryvalues of Pe could Sprenklemake

partial progress. His theoretically-derived formula for the value of a

warrantdepended on parameterswhose empiricalvalues were extremely

problematicto determine(Sprenkle,1961: 204, 212-13).

The same difficulty hit the most sophisticatedtheoreticalanalysisof

warrantsfromthis period, by Paul Samuelson in collaborationwiththe

MIT mathematicianHenry P. McKean, Jr.McKean was a world-class

specialist in stochastic calculus, the theory of stochasticprocesses in

continuoustime,whichin the yearsafterBachelier'sworkhad burgeoned

intoa keydomainofmodernprobability theory.Even withMcKean's help,

however,Samuelson'smodel (whichspace constraints preventme describ-

ing in detail) also depended,like Sprenkle's,on parametersthatseemed to

have no straightforward empiricalreferents: the expectedrateof return

rOc,

on the underlyingstock, and r,, the expected returnon the warrant

(McKean, 1965; Samuelson, 1965). A similarproblemwas encounteredin

the somewhatsimplerwork of Universityof Chicago PhD student,A.

JamesBoness. He made the simplifying assumptionthatoptiontradersare

risk-neutral,but his formulaalso involvedrOc,whichhe could estimateonly

indirectlyby findingthe value that minimizedthe differencebetween

predictedand observedoptionprices (Boness, 1964).

'The Greatest Gambling Game on Earth'

Theoreticalanalysisof warrantand option prices thus seemed alwaysto

lead to formulaeinvolvingparametersthatwere difficultor impossibleto

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 841

estimate.An alternativeapproach was to eschew a priorimodels and to

studythe relationshipbetweenwarrantand stockprices empirically. The

mostinfluential workofthiskindwas conductedby Sheen Kassouf.Aftera

mathematicsdegreefromColumbia University, Kassouf set up a success-

fultechnicalillustration

firm.He was fascinatedby the stockmarketand a

keen,ifnot alwayssuccessful,investor.In 1961, he wantedto investin the

defencecompanyTextron,but could not decide betweenbuyingits stock

or itswarrants[Kassoufinterview].He startedto examinethe relationship

betweenstockand warrantprices,findingempiricallythata simplehyper-

bolic formula

W= v C2+x2 - c

seemed roughlyto fitobservedcurvilinearrelationshipsbetweenwarrant

price,stockprice and strikeprice (Kassouf, 1962: 26).

In 1962, Kassouf returnedto Columbia to studywarrantpricingfora

PhD in economics.His earliersimplecurvefitting was replacedby econo-

metrictechniques,especiallyregressionanalysis,and he posited a more

complexrelationshipdetermining warrantprices:

w/c = [(X/C)Z + 1] 1Z - 1 (3)

wherez was an empirically-determined functionofthestockprice,exercise

price, stock price 'trend',"1time to expiration,stock dividend,and the

extentof the dilutionof existingshares thatwould occur if all warrants

were exercised(Kassouf, 1965).

Kassouf's interestin warrantswas not simplyacademic: he wanted'to

make money'tradingthem[Kassoufinterview].He had rediscovered,even

beforestartinghis PhD, an old formof securitiesarbitraget (see Weinstein,

1931: 84, 142-45). Warrantsand the correspondingstocktendedto move

together:ifthe stockprice rose, thenso did the warrantprice; ifthe stock

fell,so did thewarrant.So one could be used to offsettheriskoftheother.

If, forexample,warrantsseemed overpricedrelativeto the corresponding

stock,one could shortselltthem,hedgingthe riskby buyingsome of the

stock.Tradingof thissort,conductedby Kassouf in parallelwithhis PhD

research,enabled him 'to more than double $100,000 in just fouryears'

(Thorp and Kassouf, 1967: 32).

In 1965, freshfromhis PhD, Kassouf was appointedto the facultyof

thenewlyestablishedIrvinecampus oftheUniversity of California.There,

he was introducedto mathematician Edward 0. Thorp. Alongsideresearch

in functionalanalysisand probabilitytheory,Thorp had a long-standing

interestin casino games.While at MIT in 1959-61 he had collaborated

withthe celebratedinformation theoristClaude Shannon on a tiny,weara-

ble, analog computersystemto predictwherethe ball would be deposited

on a roulettewheel [Thorp interview].Thorp went on to devise the first

effective methodsforbeatingthe casino at blackjack,by keepingtrackof

cardsthathad alreadybeen dealt and thusidentifying situationsfavourable

to the player(Thorp, 1961; Tudball, 2002).

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

842 Social Studies of Science 33/6

Thorp and Shannon's use of theirwearable roulettecomputerwas

limitedby frequently brokenwires,but card-countingwas highlyprofit-

able. In the MIT spring recess in 1961, Thorp travelledto Nevada

equipped witha hundredUS$100 bills providedby two millionaireswith

an interestin gambling.After30 hours of blackjack,Thorp's US$10,000

had become US$21,000. He went on to devise,with computerscientist

William E. Walden of the nuclear weapons laboratoryat Los Alamos, a

method for identifying favourableside bets in the version of baccarat

played in Nevada. Thorp found, however,that beating the casino had

disadvantagesas a way of makingmoney.At a timewhenUS casinos were

controlledlargelyby organizedcriminals,therewere physicalrisks:while

Thorp was playingbaccaratin 1964, he was renderedalmostunconscious

by knock-outdropsadded to his coffee.The need to travelto places where

gamblingwas legalwas a further disadvantageto an academicwitha family

[Thorp interview].

Increasingly,Thorp's attentionswitchedto the financialmarkets.'The

greatestgamblinggame on earth is the one played daily throughthe

brokeragehouses acrossthe country',Thorp told thereadersof thehugely

successfulbook describinghis card-counting methods(Thorp, 1966: 182).

But could the biggestof casinos succumb to Thorp's mathematicalskills?

Predictingstockprices seemed too daunting:'thereis an extremelylarge

numberof variables,manyof whichI can't get any fixon'. However,he

realizedthat'I can eliminatemostofthevariablesifI thinkabout warrants

versuscommonstock' [Thorp interview]. Thorp began to sketchgraphsof

the observedrelationshipsbetweenstockand warrantprices,and meeting

Kassouf provided him with a formula (equation 3 above) for these

curves.

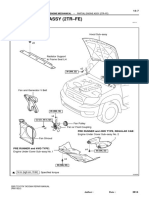

Their book, Beat theMarket(Thorp and Kassouf, 1967), explained

graphicallythe relationshipbetweenthe price of a warrant,w, and of the

underlyingcommon stock,x (see Figure 1). No warrantshould evercost

more than the underlyingstock,since it is simplyan option to buy the

latter,and thisconstraintyieldeda 'maximumvalue line'. At expiration,as

Sprenklehad noted,a warrantwould be worthlessifthestockprice,x, was

less thanthe strikeprice,c; otherwiseit would be worththe difference (x -

c). If, at any time,w < x - c, an instantarbitrageprofitcould be made by

buyingthe warrantand exercisingit (at a cost of w + c) and sellingthe

stockthus acquired forx. So the warrant'svalue at expirationwas also a

minimumvalue forit at any time.As expirationapproached,the 'normal

price curves' expressingthe value of a warrantdropped closerto its value

at expiration.

These 'normalprice curves'could thenbe used to identify overpriced

and underpricedwarrants.'2The formercould be sold short,and thelatter

bought,withthe resultantriskshedged by takinga positionin the stock

(buying stock if warrantshad been sold short; selling stock short if

warrantshad been bought). The appropriatesize of hedge, Thorp and

Kassouf explained(1967: 82), was determinedby 'the slope of thenormal

price curve at our startingposition'. If that slope were, say, 1:3, as it

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 843

FIGURE1

| v j~~~~Moth

before

A

Price of common,S

'Normalpricecurves'fora warrant.FromEdward0. Thorpand SheenT. Kassouf,Beat

the Market:A ScientificStockMarketSystem(New York:RandomHouse, 1967),31.

o Edward0. Thorpand SheenT. Kassouf.Used by permissionof RandomHouse,Inc.

S is Thorpand Kassouf'snotationforthe priceof the commonstock.

roughlyis at point (A,B) in Figure 1, the appropriatehedge ratiowas to

buy one unit of stockforeverythreewarrantssold short.Anymovements

along the normal price curve caused by small stock price fluctuations

would then have littleeffecton the value of the overallposition,because

the loss or gain on the warrantswould be balanced by a nearlyequivalent

gain or loss on the stock. Larger stockprice movementscould of course

lead to a shiftto a regionof the curvein whichthe slope differed

from1:3,

and in theirinvestmentpracticeboth Thorp and Kassouf adjusted their

hedges when thathappened (Thorp, 2002; Kassouf interview).

Initially,Thorp relied upon Kassouf's empiricalformulaforwarrant

prices (equation 3 above): as he says,'it produced ... curvesqualitatively

like the actual warrantcurves'.Yet he was not entirelysatisfiedwith it:

'quantitatively,I thinkwe both knewthattherewas somethingmore that

had to happen' [Thorp interview].He began his investigationof that

'something' in the same way as Sprenkle - applying the log-normal

distributionto work out the expected value of a warrantat expiration-

reachinga formulaequivalentto Sprenkle's(equation 1 above).

Like Sprenkle's,Thorp's formula(Thorp, 1969: 281) forthe expected

value of a warrantinvolvedthe expectedincreasein the stockprice,which

therewas no straightforward wayto estimate.He decided to approximateit

by assumingthatthe expectedvalue ofthe stockrose at the risklesstrateof

interest:he had no betterestimate,and he 'didn't thinkthat enormous

errorswould necessarilybe introduced' by the approximation.Thorp

foundthatthe resultantformulawas plausible- 'I couldn't findanything

wrong with its qualitativebehavior and with the actual forecastit was

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

844 Social Studies of Science 33/6

making'- and in 1967 he startedto use it to identifygrosslyoverpriced

optionsto sell [Thorp interview].It was formallyequivalentto the Black-

Scholes formulafor a call option (equation 5 below), except for one

feature:unlikeBlack and Scholes,Thorp did not discounttthe expected

value of the option at expirationback to the present. In the warrant

marketshe was used to, the proceeds of the shortsale of a warrantwere

retainedin theirentiretyby thebroker,and werenot availableimmediately

to the seller as Black and Scholes assumed.'3It was a relativelyminor

difference:whenThorp read Black and Scholes, he was able quicklyto see

why the two formulaedifferedand to add to his formulathe necessary

discountfactorto make themidentical(Thorp, 2002). In thebackground,

however,lay more profounddifferences of approach.

Black and Scholes

In 1965, FischerBlack,witha HarvardPhD (Black, 1964) in whatwas in

effectartificialintelligence,joined the operationsresearchgroup of the

consultancyfirmArthurD. Little,Inc. There, Black met JackTreynor,a

financialspecialistat Little [Treynorinterview].Treynorhad developed,

thoughhad not published,whatlaterbecame knownas the Capital Asset

Pricing Model (also developed, independently,by academics William

Sharpe, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin).14It was Black's (and also

Scholes's) use of thismodel thatdecisivelydifferentiated theirworkfrom

the earlierresearchon optionpricing.

The Capital Asset PricingModel provideda systematicaccount ofthe

'risk premium':the additionalreturnthat investorsdemand forholding

riskyassets.That premium,Treynorpointedout, could not depend simply

on the 'sheer magnitudeof the risk',because some riskswere 'insurable':

theycould be minimizedby diversification, by spreadingone's investments

overa broad rangeof companies (Treynor,1962: 13-14; 1999: 20). What

could not be diversifiedaway,however,was the risk of general market

fluctuations.By reasoningof this kind,Treynorshowed - and the other

developersof the model also demonstrated- that a capital asset's risk

premiumshould be proportionalto its [ (its covariancewiththe general

levelofthemarket,dividedby thevarianceof themarket).An assetwhose

f was zero, in otherwords an asset the price of whichwas uncorrelated

withtheoveralllevelofthemarket,had no riskpremium(anyspecificrisks

involvedin holdingit could be diversified away),and investorsin it should

earn onlyr,therisklessrateofinterest. As theasset's 3 increased,so should

its riskpremium.

The Capital Asset PricingModel was an elegantpiece of theoretical

reasoning.Its co-developerTreynor became Black's mentorin whatwas for

Black thenew fieldoffinance,so it is not surprisingthatwhenBlack began

his own workin financeit was by tryingto applythe model to a rangeof

assets otherthan stock (whichhad been its main initialfieldof applica-

tion). Also importantas a resourceforBlack's researchwas a specificpiece

of jointworkwithTreynoron how companies should value cash flowsin

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 845

makingtheirinvestmentdecisions.This was the problemthat had most

directlyinspiredTreynor's development of the Capital Asset Pricing

Model, and the aspect of it on whichBlack and Treynorcollaboratedhad

involvedTreynorwritingan expressionforthechangein thevalue ofa cash

flowin a short,finitetimeintervalAt; expandingthe expressionusingthe

standardcalculus technique ofTaylorexpansion;takingexpectedvalues;

droppingthe termsof orderAt2and higher;dividingby At; and lettingAt

tend to zero so that the finitedifferenceequation became a differential

equation.Treynor'soriginalversionof the latterwas in errorbecause he

had leftout a second derivativethat did not vanish,but Black and he

workedout how to correctthe differential equation by adding the corre-

spondingterm.5

Amongstthe assets to which Black tried to apply the Capital Asset

PricingModel werewarrants.His startingpointwas directlymodelled on

his joint workwithTreynor,withw, the value of the warrant,takingthe

place of cash flow,and x, the stockprice,replacingthe stochastically

time-

dependent 'informationvariables' of the earlier problem. If Aw is the

change in the value of the warrantin timeinterval(t, t + At),

Aw= w(x + Ax, t + At) - w(x,t)

where Ax is the change in stock price over the interval.Black then

expanded thisexpressionin a Taylorseriesand took expectedvalues:

aw aw 1 a22 w 1 a2w

E(Aw) E(Ax) + At + - E(Ax2) + AtE(Ax) +- 2 At2

a3x a3t 2 aX2 a3xait 2 at'

whereE designates'expectedvalue' and higherordertermsare dropped.

Black thenassumed thatthe Capital Asset PricingModel applied both to

the stock and warrant,so that E(Ax) and E(Aw) would depend on,

respectively,the [ of the stockand the [ of the warrant.He also assumed

that the stock price followeda log-normalrandom walk and thatit was

permissible'to eliminatetermsthatare second orderin At'.These assump-

tions, a little manipulation,and lettingAt tend to zero, yielded the

differentialequation:

aw aw 1 3a2w

-= rw--rX-a --r X2a (4)

where r is the risklessrate of interestand o- the volatilityt

of the stock

price.16

'I spentmany,manydays tryingto findthe solutionto thatequation',

Black later recalled: 'I ... had never spent much time on differential

equations,so I didn't knowthe standardmethodsused to solve problems

like that'. He was 'fascinated'thatin the differential

equation apparently

key featuresof the problem (notablythe stock's 1Band thus its expected

return,a pervasivefeaturein earliertheoreticalworkon optionpricing)no

longerappeared. 'But I was stillunable to come up withthe formula.So I

put the problemaside and workedon otherthings'(Black, 1989: 5-6).

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

846 Social Studies of Science 33/6

In the autumn of 1968, however,Black (stillworkingforArthurD.

Little in Cambridge,MA) met Myron Scholes, a young researcherwho

had just joined the financegroupin MIT's Sloan School of Management.

The pair teamed up withfinancescholar Michael Jensento conduct an

empiricaltestof the Capital Asset PricingModel, whichwas stilllargelya

theoreticalpostulate. Scholes also became interestedin warrantpricing,

not, it seems, throughBlack's influencebut throughsupervisingan MIT

Master's dissertationon the topic (Scholes, 1998). Scholes' PhD thesis

(Scholes, 1970) involvedthe analysisof securitiesas potentialsubstitutes

for each other,with the potentialfor arbitrageensuringthat securities

whose risks are alike will offersimilarexpected returns.Scholes' PhD

adviser,Merton H. Miller,had introducedthisformof theoreticalargu-

ment- 'arbitrageproof'- in whatby 1970 was alreadyseen as classicwork

withFranco Modigliani (Modiglianiand Miller, 1958). Scholes startedto

investigatewhethersimilarreasoningcould be applied to warrantpricing,

and began to considerthehedgedportfolioformedbybuyingwarrantsand

shortsellingthe underlyingstock(Scholes, 1998: 480).

The hedged portfoliohad been the centralidea of Thorp and Kas-

souf's Beat theMarket(1967), thoughScholes had not yetread the book

[Scholes interview].Scholes' goal, in any case, was different.Thorp and

Kassouf's hedgedportfoliowas designedto earnhigh returns withlow risk

in real markets.Scholes' was a desired theoreticalartifact.He wanted a

portfoliowitha [ ofzero: thatis, withno correlationwiththe overalllevel

of the market.If such a portfoliocould be created, the Capital Asset

PricingModel impliedthatit would earn, not high returns,but onlythe

riskless rate of interest,r. It would thus not be an unduly enticing

investment, but knowingthe rate of returnon the hedged portfoliomight

solve the problemof warrantpricing.

What Scholes could not workout, however,was how to constructa

zero-r portfolio.He could see thatthe quantityof sharesthathad to be

sold shortmustchangewithtimeand withchangesin the stockprice,but

he could not see how to determinethatquantity.'[A]fterworkingon this

concept,offand on, I stillcouldn'tfigureout analytically how manyshares

of stockto sell shortto createa zero-betaportfolio'(Scholes, 1998: 480).

Like Black, Scholes was stymied.Then, in 'the summeror earlyfall of

and Black describedthe different

1969', Scholes told Black of his efforts,

approach he had taken, in particular showing Scholes the Taylor series

expansion of the warrant price (Scholes, 1998: 480). The two men then

foundhow to constructa zero-[ portfolio.Ifthestockpricechangedbythe

small amountAx,the optionpricewould alterby aAx. So thenecessary

3w ~ 3ax

hedge was to shortsell a quantityax of stockforeverywarrantheld.This

a3x

was the same conclusionThorp and Kassouf had arrivedat: aw is their

ax

hedgingratio,the slope of the curveof w plottedagainstx as in Figure 1.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 847

Whilethe resultwas in thatsense equivalent,it was embeddedin quite

a differentchain ofreasoning.Althoughtheprecisewayin whichBlack and

Scholes arguedthe pointevolvedas theywrotesuccessiveversionsof their

paper,'7 the crux of their mathematicalanalysis was that the hedged

portfoliomust earn the risklessrate of interest.The hedged portfoliowas

not entirelyfree from risk, they argued in August 1970, because the

hedging would not be exact if the stock price altered significantly and

because the value of an option alteredas expirationbecame closer.The

change in value of the hedged portfolioresultingfromstockprice move-

mentswould,however,depend onlyon themagnitudeofthosemovements

not on theirsign.It was, therefore, thekindofriskthatcould be diversified

away. So, according to the Capital Asset Pricing Model, the hedged

portfoliocould earn onlythe risklessrate of interest(Black and Scholes,

1970a: 6). In otherwords,the expectedreturnon the hedged portfolioin

the shorttimeinterval(t, t + At) is justitspriceat timet multipliedby rAt.

Simple manipulationof theTaylorexpansionof w(x + Ax, t + At) led to a

finitedifferenceequation that could be transformedinto a differential

equation by lettingAt tend to zero, and to equation 4 above: the Black-

Scholes optionpricingequation,as it was soon to be called.

As noted above,Black had been unable to solve equation4, but he and

Scholes now returnedto the problem.It was, however,stillnot obvious

how to proceed. Like Black, Scholes was 'amazed thatthe expectedrateof

returnon the underlyingstock did not appear in [equation 4]' (Scholes,

1998: 481). This promptedBlack and Scholes to experiment, as Thorp had

done, withsettingthe expectedreturnon the stockas the risklessrate,r.

They substitutedr fork in Sprenkle'sformulaforthe expectedvalue of a

warrantat expiration(equation 1 above). To get the warrantprice, they

thenhad to discounttthatterminalvalue back to the present.How could

theydo that?'Rathersuddenly,it came to us', Black laterrecalled.'If the

stockhad an expectedreturnequal to the [riskless]interestrate,so would

the option. Afterall, if all the stock's risk could be diversifiedaway, so

could all the option'srisk.If thebeta ofthe stockwerezero,thebeta ofthe

optionwould have to be zero too. ... [T]he discountratethatwould take

us fromtheoption'sexpectedfuturevalue to itspresentvalue would always

be the [riskless]interestrate' (Black, 1989: 6). These modificationsto

Sprenkle'sformulaled to the followingformulaforthe value of a warrant

or call option:

ln(x/c) + (r + 2o2)(t*- t)

w=xN[-

0-1 t* - t

+ (r-2-

ln(x/c -t t)

-c[exp{r(t- t*)}]N[In(xlc) + (r- (5

0-vt* -t

wherec is the strikeprice,o-the volatilityof the stock,t* the expirationof

the option,and N the Gaussian distribution function.Instead offacingthe

difficult

taskof directlysolvingequation 4, all Black and Scholes had now

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

848 Social Studies of Science 33/6

to do was show by differentiating

equation 5 thatit (the Black-Scholescall

optionor warrantformula)was a solutionof equation 4.

Merton

Black's and Scholes' tinkeringwith Sprenkle's expected value formula

(equation 1 above) was in one sense no different fromBoness' orThorp's.

However,Boness' justification forhis choice ofexpectedrateofreturnwas

empirical- he chose 'the rateof appreciationmost consistentwithmarket

pricesofputs and calls' (Boness, 1964: 170) - and Thorp freelyadmitshe

'guessed' that the rightthingto do was to set the stock's rate of return

equal to the risklessrate: it was 'guessworknot proof' [Thorp interview].

Black and Scholes, on the otherhand, could prove mathematically that

theircall option formula(equation 5) was a solutionto theirdifferential

equation (equation 4), and the latterhad a clear theoreticaljustification.

It was a justification

apparentlyintimately bound up withthe Capital

Asset PricingModel. Not onlywas the model drawnon explicitlyin both

the equation's derivations,but it also made Black's and Scholes' entire

mathematicalapproach seem permissible.Like all othersworkingon the

problem in the 1950s and 1960s (with the exception of Samuelson,

McKean, and Merton), Black and Scholes used ordinarycalculus-Taylor

seriesexpansion,and so on - but in a contextin whichx, the stockprice,

was known to vary stochastically.Neither Black nor Scholes knew the

mathematicaltheoryneeded to do calculus rigorouslyin a stochastic

environment, but the Capital Asset PricingModel providedan economic

forwhatmightotherwisehave seemed dangerouslyunrigorous

justification

mathematics.'We did not knowwhetherour formulation was exact', says

Scholes, 'but intuitively we thoughtinvestorscould diversifyaway any

residualriskthatwas left'(Scholes, 1998: 483).

As noted above, Black had been a close colleague of the Capital Asset

PricingModel's co-developer,Treynor,whileScholes had done his gradu-

ate work at the Universityof Chicago, one of the two leading sites of

financialeconomics,wherethe model was seen as an exemplarycontribu-

tionto thefield.However,at the othermain site,MIT, the originalversion

of the Capital Asset PricingModel was regardedmuch less positively. The

model rested upon the 'mean-variance'view of portfolioselection:that

investorscould be modelled as guided only by theirexpectationsof the

returnson investmentsand their risks as measured by the expected

standarddeviationor varianceof returns.Unless returnsfolloweda joint

normal distribution(which was regardedas ruled out, because it would

imply,as noted above, a non-zeroprobabilityof negativeprices), mean-

varianceanalysisseemed to restupon a specificformof 'utilityfunction'

(the functionthatcharacterizesthe relationshipbetweenthe returnon an

investor'sportfolio,y, and his or her preferences).Mean-varianceanalysis

seemed to implythat investors'utilityfunctionswere quadratic: that is,

theycontainedonlytermsin y and y2.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 849

For MIT's Paul Samuelson, the assumptionof quadratic utilitywas

over-specific- one of his earliestcontributions to economics (Samuelson,

1938) had been his 'revealedpreference'theory,designedto eliminatethe

non-empiricalaspects of utilityanalysis- and a 'bad ... representation of

human behaviour' [Samuelson interview].8Seen fromChicago, Samuel-

son's objections were 'quibbles' [Fama interview]when set against the

virtuesof the Capital Asset PricingModel: 'he's got to rememberwhat

Milton Friedmansaid - "Never mind about assumptions.What countsis,

how good are the predictions?"' [Millerinterview;see Friedman, 1953].

Nevertheless,theywere objectionsthat weighedheavilywith Robert C.

Merton. Son of the social theoristand sociologist of science Robert

K. Merton, he switchedin autumn 1967 fromgraduateworkin applied

mathematicsat the CaliforniaInstituteofTechnologyto studyeconomics

at MIT. He had been an amateur investorsince aged 10 or 11, had

graduatedfromstocksto optionsand warrants,and came to realize'thatI

had a muchbetterintuitionand "feel"intoeconomicmattersthanphysical

ones'. In spring1968, Samuelson appointedthe mathematically-talented

youngMerton as his researchassistant,even allocatinghim a desk inside

his MIT office(Merton interview;Merton, 1998: 15-16).

It was not simplya matterof Merton findingthe assumptionsunder-

pinningthe standardCapital AssetPricingModel 'objectionable'(Merton,

1970: 2). At the centreof Merton's workwas the effortto replace simple

'one-period' models of that kind with more sophisticated'continuous-

time' models. In the latter,not only did the returnson assets varyin a

continuousstochasticfashion,but individualstook decisions about port-

folio selection (and also consumption)continuously,not just at discrete

points in time. In any time interval,howevershort, individualscould

change the compositionof theirinvestmentportfolios.Compared with

'discrete-time'models, 'the continuous-timemodels are mathematically

morecomplex',saysMerton.He quicklybecame convinced,however,that

'the derivedresultsofthe continuous-time models wereoftenmoreprecise

and easier to interpretthan their discrete-timecounterparts'(Merton,

1998: 18-19). His 'intertemporal'capital asset pricingmodel (Merton,

1973), forexample,did not necessitatethe 'quadratic utility'assumption

of the original.

With continuous-timestochasticprocesses at the centreof his work,

Merton feltthe need not just to make ad hoc adjustmentsto standard

calculus but to learn stochasticcalculus. It was not yetpart of economists'

mathematicalrepertoire(it was above all Merton who introducedit), but

by the late 1960s a number of textbooktreatmentsby mathematicians

(such as Cox and Miller, 1965 and Kushner, 1967) had been published,

and Merton used these to teach himselfthe subject [Merton interview].

He rejected as unsuitable the 'symmetrized'formulationof stochastic

integration by R.L. Stratonovich(1966): it was easierto use forthosewith

experienceonlyof ordinarycalculus,but whenapplied to pricesit in effect

allowedinvestorsan illegitimate peek intothefuture.Mertonchose instead

the original 1940s' definitionof the stochasticintegralby the Japanese

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

850 Social Studies of Science 33/6

mathematician,Kiyosi It6, and Uto'sassociated apparatus for handling

stochasticdifferentialequations (StroockandVaradhan,1987).

Amongst the problems on which Merton worked, both with

Samuelson and independently, was warrantpricing,and theresultantwork

formed two of the five chapters of his September 1970 PhD thesis

(Samuelson and Merton, 1969; Merton, 1970: chapters4 and 5). Black

and Scholes read the 1969 paper in which Samuelson and Merton de-

scribedtheirjointwork,but did not immediatelytell themof the progress

theyhad made: therewas 'friendlyrivalrybetweenthe two teams', says

Scholes (1998: 483). In the earlyautumnof 1970, however,Scholes did

discusswithMertonhis workwithBlack. Mertonimmediately appreciated

that this workwas a 'significant"break-through" ' (Merton, 1973: 142),

and it was Merton, for example, who christenedequation 4 the 'Black-

Scholes' equation. Given Merton's criticalattitudeto the Capital Asset

PricingModel, however,it is also not surprisingthathe also believedthat

'such an importantresult deserves a rigorousderivation',not just the

'intuitivelyappealing'one Black and Scholes had provided(Merton, 1973:

161-62). 'What I sort of argued with them [Black and Scholes]', says

Merton,'was, ifit depended on the [Capital] Asset PricingModel, whyis

it when you look at the final formula [equation 4] nothingabout risk

appears at all? In fact,it's perfectlyconsistentwith a risk-neutralworld'

[Mertoninterview].

So Merton set to workapplyinghis continuous-timemodel and Ito

calculus to theBlack-Scholeshedgedportfolio.'I looked at thisthing',says

Merton, 'and I realized that if you did ... dynamictrading ... if you

actually[traded]literallycontinuously, thenin fact,yeah,you could getrid

of the risk,but not just the systematicrisk,all the risk'.Not onlydid the

hedged portfoliohave zero [ in the continuous-time limit(Merton'sinitial

doubts on thispointwere assuaged),19'but you actuallyget a zero sigma':

that is, no variance of returnon the hedged portfolio.So the hedged

portfoliocan earn onlythe risklessrate of interest,'not forthe reason of

[the Capital] Asset PricingModel but ... to avoid arbitrage,or money

machine': a way of generatingcertain profitswith no net investment

[Merton interview].For Merton, then, the 'key to the Black-Scholes

analysis' was an assumptionBlack and Scholes did not initiallymake:

continuous trading,the capacity to adjust a portfolioat all times and

instantaneously. '[O]nly in the instantaneouslimitare the warrantprice

and stockprice perfectly correlated,whichis whatis requiredto formthe

"perfect"hedge' (Merton, 1972: 38).

Black and Scholes were not initiallyconvincedof the correctnessof

Merton's approach. Merton's additionalassumption- his world of con-

tinuous-timetrading- was a radical abstraction,and in a January1971

draftof theirpaper on optionpricingBlack and Scholes even claimedthat

equilibriumprices in capital marketscould not have characteristicsas-

sumed by Merton's analysis(Black and Scholes, 1971: 20). Merton, in

turn,told FischerBlack in a 1972 letterthat'I ... do not understandyour

reluctance to accept that the standard form of CAPM [Capital Asset

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 851

PricingModel] just does not work'(Merton, 1972). Despite thisdisagree-

ment,Black and Scholes used whatwas essentiallyMerton's revisedform

of theirderivationin the final,publishedversionof theirpaper (Black and

Scholes, 1973), though they also presentedBlack's originalderivation,

whichdrew directlyon the Capital Asset PricingModel. Black, however,

remainedambivalentabout Merton'sderivation,tellinga 1989 interviewer

that'I'm stillmore fond' of the Capital Asset PricingModel derivation:

'[T]here maybe reasonswhyarbitrageis not practical,forexampletrading

costs'. (If tradingincurseventinytransactioncosts,continuousadjustment

of a portfoliois infeasible.)Merton's derivation'is more intellectual[ly]

elegantbut it relies on stricterassumptions,so I don't thinkit's reallyas

robust'20

Black, indeed,came to expressdoubts even about the centralintuition

of orthodoxfinancialeconomics,that modern capital marketswere effi-

cient (in otherwords thatprices in themincorporateall knowninforma-

tion). Efficiencyheld, he suggested,only in a diluted sense: 'we might

definean efficientmarketas one in which price is withina factorof 2

of value'. Black noted thatthispositionwas intermediatebetweenthatof

Merton,who defendedthe efficient markethypothesis,and thatof'behav-

ioural' financetheoristRobert Shiller: 'Deviations fromefficiency seem

moresignificant in myworldthanin Merton's,but muchless significant in

my world than in Shiller's' (Black, 1986: 533; see Merton, 1987 and

Shiller,1989).

The Equation and the World

It was not immediatelyobviousto all thatwhatBlack, Scholes and Merton

had done was a fundamentalbreakthrough. The JournalofPoliticalEcon-

omyoriginallyrejectedBlack and Scholes' paper because, its editortold

Black, optionpricingwas too specializeda topic to meritpublicationin a

generaleconomicjournal (Gordon, 1970), and thepaper was also rejected

by the ReviewofEconomicsand Statistics(Scholes, 1997: 484). True, the

emergingnew breed of financialeconomistsquicklysaw the elegance of

theBlack-Scholessolution.All theparametersin equations4 and 5 seemed

readilyobservableempirically:therewere none of the intractableestima-

tion problemsof earliertheoreticalsolutions.That alone, however,does

not account forthe wider impact of the Black-Scholes-Mertonwork. It

does not explain, for example, how a paper originallyrejected by an

economicjournalas too specializedshouldwin a Nobel prizein economics

(Scholes and Merton were awarded the prize in 1997; Black died in

1995).

That the world came to embrace the Black-Scholes equation was in

part because the worldwas changing- see the remarksat the startof the

paper on the transformation of academic finance and the profession-

alizationofUS businessschools- and in partbecause theequation (unlike,

forexample,Bachelier'swork)changedtheworld.2'Thelatterwas the case

in four senses. First, the Black-Scholes equation seems to have altered

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

852 Social Studies of Science 33/6

patterns of option prices. After constructingtheir call-option pricing

formula(equation 5 above), Black and Scholes testedits empiricalvalidity

forthe ad hoc NewYork optionsmarket,usinga broker'sdiariesin which

were'recordedall optioncontractswrittenforhis customers'.They found

only an approximatefit:'in generalwriters[the sellersof options] obtain

favorableprices, and ... there tends to be a systematicmispricingof

options as a functionof the varianceof returnsof the stock' (Black and

Scholes, 1972: 403, 413). A moreorganized,continuousoptionsexchange

was establishedin Chicago in 1973, but Scholes' studentDan Galai also

found that prices thereinitiallydifferedfromthe Black-Scholes model,

indeed to a greaterextentthanin the New Yorkmarket(Galai, 1977).

By the second half of the 1970s, however,discrepanciesbetween

patternsof optionpricingin Chicago and theBlack-Scholesmodel dimini-

shed to the pointof economicinsignificance (the ad hoc NewYorkmarket

quicklywitheredafterChicago and other organized options exchanges

opened). The reasons are various,but theyinclude the use of the Black-

Scholes model as a guide to arbitrage.Black set up a servicesellingsheets

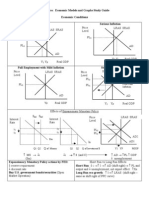

of theoreticaloptionpricesto marketparticipants(see Figure 2). Options

marketmakerstused those sheets and othermaterialexemplifications of

the Black-Scholes model to identifyrelativelyover-pricedand under-

pricedoptionson the same stock,sold theformerand hedged theirriskby

buyingthelatter.In so doing,theyalteredpatternsofpricingin a waythat

increasedthe validityof the model's predictions,in particularhelpingthe

model to pass its key econometrictest: that the impliedvolatilityt of all

options on the same stock with the same expirationshould be identical

(MacKenzie and Millo, forthcoming).

The second world-changing,performativeaspect of the Black-

Scholes-Mertonworkwas deeper than its use in arbitrage.In its math-

ematicalassumptions,the equation embodied a world,so to speak. (From

this viewpoint,the differencesbetween the Black-Scholes world and

Merton's worldare less importantthan theircommonalities.)In the final

publishedversionof theiroptionpricingpaper in 1973, Black and Scholes

spelled out these assumptions,whichincludednot just the basic assump-

tionthatthe'stockpricefollowsa [lognormal]randomwalkin continuous

time', but also assumptionsabout marketconditions:that thereare 'no

transactioncosts in buyingor sellingthe stock or the option'; that it is

'possible to borrowany fractionof the price of a securityto buy it or to

hold it', at the risklessrate of interest;and that these are 'no penalties

to shortselling'(Black and Scholes, 1973: 640).

In 1973, these assumptions about market conditions were wildly

unrealistic.Commissions (a key transactioncost) were high everywhere.

Investorscould not purchasestockentirelyon credit- in theUSA thiswas

banned by the Federal Reserve'sfamous'RegulationT' - and such loans

would be at a rateofinterestin excess oftherisklessrate.Shortsellingwas

legallyconstrainedand financiallypenalized: stock lenders retainedthe

proceedsof a shortsale as collateralfortheloan, and refusedto pass on all

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and itsWorlds 853

m

m m

$A

N 0

m

40 M

E -0

0

%A m

x

IA

0

0

r 40

m 0

m

IA M

0 C, IP 6.

4.44 m

P. 0, 0, V 0,

X

'o -,D c'.

I I A 14 00 00 U >

C: C!

0

+0

$A $A

m m

.00.

410

V- 0 0 C: at 10 r- N_

m

of 09.41" .00 0110 -

r r 0 $A

.04"I 11

91 110. 11 2a AI,

W" 1-000I.I.O. IAD

low :Vv":wOv%w

-O.-M ;; .0

m 0 .2

J.; -44 J,A

o 0

$A

4) CL

f4 f4

IrVywipt,CC" 19Al

1. 'm 4-1

;,:;.o 0'"WC0V."_. W.1014 0

I*000

0

o tftre ON-

V

t"" 00 00 00 WO 00 4v- oo 0 VA- g-8:8

A m

& >

r- r4 . $A

.11:00,0430

. . . . . . 0

E

::Ipvw4pf"Q:! at: a M 4-1 m

6-00 0

P.

c Cb

MNN"" Om

c

N a

-4A : Q

>

$A m 0

all N 0

04 a f- M 10 ft: 44 0.4 _,0 a C4

k"';

I.rt 12

lu, 10 Al el 0 el,,

C., M

N

:99"0000 -vn

V 0 -

,Coo 1"4 1.0 11, 0

a 00

1: 1 0 0 0

bi 0 0 0 0 ulrq- rt U >. 0 4-0

$A

,,IC: POV0.0

0- tgS*r4CI0CII* W,,- -ergroco t

m

.4 ::!S:S n X M 4,

-.00:0000 N e4

0 0: ct0 P4 0)

21000 r 0 0 0

14 14

4, $A

W 1. 400 t

10P.

4 0 b, 4t la 11I

r!t =

0

v"Alroo roq "O

' .4-0

0 0 bl C 4-0 C; m

rt- -I1 1: 0. I 0

$A

m

mv 0 a mf 0 r, v NZ 0 0 I! -Drq ft-At`Vm:r:

101,"IO 110.

of

W

In W.

16 Q

w:T I

10 11: 1.111, m M

M% op 0. 04 Is I 0 0 -n 90 W.'s a o o o 14 V4 a 0 0

0 C,

0 0 N C 91 .0 , C)

m

"000

1- 0 0

U, M

E M

go, el'00,

1.10 10,

Pr" P-

lo,," b' V

4) 4.0

- >

10

6 P14 i : !

0 $A 0

0 v% f 10 'a on MD., am '46 IoCN

10 0, ,go oco ;Fmc; C,.;. ;wO , "a V, W, 0 0 $A

13 0 nr4-% -1 r4 . . . . . .

."WOOCC, CO W

B.,

.0

= *1 N

la 00 :90 (ri

4 CZ r- 'r.. 0 0

-"If.04.4000 0 4DN 0 0 0 a r- A r C) 0

11

6-

0 o 00 0 $A

L. m

",'A 0 ft a 0 0 orlococ)

C

2 CO, .0

ft-t

100

C:

14.C:_.ZO0

bl- I 19i

0

Dr-- 10

OOC

P

0 = r

00

VOn

1.11.10 >, E

$A

0

bl

V

t

=

0 %A

%A

m

M

E

$A $A JA

M

%A

%A E

M

%A

%A

m m

m E

LU m

0 X

m 0

0 "WI 0. 4-

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

854 Social Studies of Science 33/6

(or sometimes any) of the interestearned on those proceeds [Thorp

interview].

Since 1973, however,the Black-Scholes-Merton assumptionshave

become, while still not completelyrealistic,a great deal more so (see

MacKenzie and Millo, forthcoming).In listingthese assumptions,Black

and Scholes wrote:'we willassume "ideal conditions"in themarketforthe

stockand fortheoption' (Black and Scholes, 1973: 640). Of course,'ideal'

here means simplifiedand thus mathematically tractable,like the physi-

surface:

cist's frictionless non-zero transactioncosts and constraintson

borrowingand shortsellinghugely complicate the optionpricingproblem.

'Ideal', however,also connotes the way thingsought to be. This was not

Black and Scholes' intendedimplication:neitherwas an activistin relation

to the politics of markets.From the early 1970s onwards,however,an

increasingly influentialnumberof economistsand otherswereactivistsfor

the 'freemarket'ideal.

Their activities(along withotherfactors,such as the role of techno-

logical change in reducing transactioncosts) helped make the world

embodiedin the Black-Scholes-Mertonassumptionsabout marketcondi-

tions more real. The Black-Scholes-Merton analysis itselfassisted this

processby helpingto legitimizeoptionstradingand thushelpingto create

the efficient,liquid marketsposited by the model. The Chicago Board

Options Exchange'scounsel recalls:

Black-Scholes was reallywhat enabled the exchange to thrive.... [I]t

gave a lot of legitimacyto the whole notions of hedging and efficient

pricing,whereaswe werefaced,in the late 60s-early70s withthe issue of

gambling.That issue fell away, and I thinkBlack-Scholes made it fall

away.It wasn'tspeculationor gambling,itwas efficient

pricing.I thinkthe

SEC [Securitiesand Exchange Commission] very quickly thoughtof

optionsas a usefulmechanismin the securitiesmarketsand it's probably

- that'smy judgement- the effectsof Black-Scholes. I neverheard the

word'gambling'again in relationto options. [Rissmaninterview]

The Black-Scholes-Mertonmodel also had more specificimpactson the

natureof the marketsit analysed.Earlierupsurgesof optionstradinghad

typicallybeen reversed,arguablybecause option prices had usuallybeen

'too high' in the sense that theymade options a poor purchase: options

could too seldom be exercisedprofitably (Kairys and Valerio,1997). The

availabilityof the Black-Scholes formula,and its associatedhedgingtech-

niques, gave participants the confidenceto writeoptionsat lowerprices,

again helpingoptionsexchanges to grow and to prosper,becomingmore

likethemarketspositedby thetheory.The Black-Scholesanalysiswas also

used to freehedgingby options marketmakerstfromthe constraintsof

RegulationT. So long as theirstockpositionswereclose to the theoretical

hedging ratio ( ), theywere allowed to constructsuch hedges using

ax

entirelyborrowedfunds(Millo, forthcoming). direct

It was a delightfully

the model being used to make one of its key

loop of performativity:

assumptionsa reality.

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.52 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:26:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MacKenzie: An Equation and its Worlds 855

Third, the Black-Scholes-Mertonsolutionto the problemof option