Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dying and Death

Dying and Death

Uploaded by

Vedant Tapadia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views16 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views16 pagesDying and Death

Dying and Death

Uploaded by

Vedant TapadiaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

ia preteen,

ace

ommend 2

WOMEN

AGING

WITH

KNOWLEDGE

ws

A TonewstoNe Book

Pususien sy

Stow & Scnuster

NewYork London Toronto

Swiney Tokyo Singepore

THE NEW

OURSELVES,

GROWING

OLDER

a

PAULA B. DORESS-WORTERS

AND DIANA LASKIN SIEGAL

IN COOPERATION WITH THE

BOSTON WOMEN’S HEALTH BOOK COLLECTIVE

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROSELAINE PERKIS

CONTENTS

+

Foreword to the 1987 Edition xi

Foreword to the 1994 Edition xiii

Project Coordinator's Preface xvi

Preface to the 1994 Edition xix

‘THE POTENTIAL OF THE SECOND HALF OF LIFE xx!

AGING WELL

1. AGING AND WELL-BEING 3.

2. HABITS WORTH CHANGING 22

3, OUR LOOKS AND OUR LLiVes 38

4. WEIGHTY IssUES 47

5. EATING WELL 52

6. MOVING FOR HEALTH 64

LIVING WITH OURSELVES AND OTHERS AS WE AGE,

7. SEXUALITY IN THE SECOND HALF OF LIFE 81

8. BIRTH CONTROL FOR WOMEN IN MIDLIFE 101

9. CHILDBEARING IN MIDLIFE 108

10. EXPERIENCING OUR CHANGE OF LIFE: MENOPAUSE 118.

1, RELATIONSHIPS IN MIDDLE AND LATER LIFE 133

12, HOUSING ALTERNATIVES AND LIVING

ARRANGEMENTS 151

13. WORK AND RETIREMENT 169

14, MONEY MATTERS: THE ECONOMICS OF AGING FOR

WoMEN 187

15, CAREGIVING 204

a ,

UNDERSTANDING, PREVENTING,

AND MANAGING MEDICAL PROBLEMS

16, WOMEN'S HEALTH AND REFORMING THE MEDICAL-CARE

‘SYSTEM 221

17, NURSING Homes 249

18, JOINT AND MUSCLE PAIN, ARTHRITIS, AND RHEUMATIC i

DisorDers 262

19. OSTEOPOROSIS AND FRACTURE PREVENTION 279

20, DENTALHEALTH 293

21, URINARY INCONTINENCE 300

22. HYSTERECTOMY AND OOPHORECTOMY 315

23. HYPERTENSION, HEART DISEASE, AND STROKE 333 ‘

24. CANCER 347

25. DIABETES 374

26. GALLSTONES AND GALLBLADDER DISEASE 382

27. VISION, HEARING, AND OTHER SENSORY LOSS ASSOCIATED

WITH AGING 389

28. MEMORY LAPSE AND MEMORY Loss 403.

29. DYINGAND DEATH 415

30, CHANGING SOCIETY AND OURSELVES 427

RESOURCES

General Resources 441 * Agingand Well-Being 447 © Habits Worth Changing 450

* Our Looks and Our Lives 454% Weighty Issues 454 © EatingWell 456 +

‘Moving for Health 458 + Secualityin the Second Halfof Life 459 © Birth Control

for Women in Midlife 462 + Childbearing in Midlife 463 + Experiencing Our Change

of Life: Menopause 466 + Relationships in Middle and Later Life 468 © Housing

Alternatives and Living Arrangements 472 * Workand Retirement 474 © Money

‘Matters: The Economics of Aging for Women 477 + Caregiving 479 + General

Health 482 + Women's Health and Reforming the Medical-Care System 484

Nursing Homes 487 + Joinrand Muscle Pain, Arthritis, and Rheumatic

Disorders 489 + Osteoporosisand Fracture Prevention 491 « Dental Health 491

‘+ Urinary Incontinence 492+ Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy 493 +

Hypertensiun, Heart Disease, and Sicoke 494 + Carer 494..% Diabetes 497 +

Gallstones and Gallbiadier Disease 493. + "Vision, Hearing, and Uther Sensory Loss

Associated with Aging 498 * Memory Lapseand Memory Loss 501 * Dyingand

Death 502 + Changing Society and Ourselves: 508

Index 507

ne cee ce ee

UPDATE BY PAULA. DORESS WORTERS WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO ANNE ARSENAL

URCES FOR THIS CHAPTER ON PAGES 5024

{ih many cultures, preparing for and making

sense of death is the work of women, especially

of old women, Whether or not it’s fair or best,

women in most societies, including our own, still

act as the nurturers, caregivers, and custodians

fof those near death. Even with the removal of

(death to the institutional sphere, dying remains

he province of women who work in those insti-

rations.

last person most of us see on earth is a woman—the

‘iurse’s aide (significantly one of the east paid aid least

valued workers in our society)... These are, in a sense,

the midwives of death!

Thus, it is most often women who meet the

emotional and pragmatic needs surrounding

death,

By the age. of fifty-seven I had nursed my husband

‘through terminal cancer, lived through widowhood, and

been close to two dear friends who died. 1 assisted one

friend and supported her family through the process of

her committing suicide, 1 feel that my middle years have

been significant in bringing me into close and familiar

contact with dying and death,

BEREAVEMENT AND GRIEF

Grief is a normal reaction to the stress of losing

someone. It is not a pathological reaction that

needs to be “cured.” According to Phyllis R. Sil-

verman, founder of the widow-to-widow move-

ment, we may go through several phases of

grieving the loss of someone we care deep

About. At first, we may fecl numb or dazed,

tunable to believe that such a grievous loss could

have happened. That numbness often carries us

through the first days and weeks, allowing us to

function. Gradually, we begin to come to terms

with the reality of the loss, realizing that we can

no longer live as before. Eventually, when we can

remember our loved one with less pain, most of

us accommodate to our loss. Then we restruc-

ture our lives to make room for new roles and

relationships? - :

The following is excerpted from ‘a woman's

journal recording her feelings about her lover’.

death overa period of years:

Inwhat later seemed to be extraordinary word usage, the

doctor called me to say the operation on Karen was “sue

cessful.” They resectioned her colon and took out the

415

+ THE New OURSELVES, Growine OLDER +

ltonor, she would not need a colostomy. But the tumor

hhas metastasized and she will die: six months to two

years is all they give her. No real hope.

tis 2:30 Aas and T cant sleep because of rage at

God, and then because of guilt. And because of fear jor

nyself, How will live without Karen to tell me Tam brit

liant and beautiful?

Images run through my head. Her hand warming my

asthma-congested chest. Her step—quick, strong, fast up

the stairs. As I remember that sound, I smile; the pain

recedes. But if shut my journal, the pain will return.

Does everyone who is dying look bewildered? Her

head ir my lap: her body spooned in pain, Dying means

deperddency. Pain, Listlessness. Fever. Exhaustion. Dying

is frightening.

Death is frat, but dying can drag on and on and on,

destroying everyone. It saps the strength of the healthy

‘and makes them sick

My first birthday without her. Our anniversary. Her

first birthday dead. My first Christmas and first New Year

without her. One year it was the greatest New Year of my

life, and the nest year the woman who gave it fo me was

dead.

Each marker brings Karen to me and takes her. Soon

any first spring without her. My first summer. Then a year

since I last saw her will pass. A year since her death; a

‘year since her funeral. And I will put «@ headstone in my

heart: Karen, my dearest?

Any one loss can remind us of all the other

losses we have known—especially the earliest

ones, which might not have been fully under-

stood or explo:

When ey lover died I was fifty-six. Over the next two

years Irelived, in away, al ofthe other great saiinesses of

‘ny life—when my father left us when I was little, my

mother’s death, the endings of other love affairs. I don't

think I had realized how much there was for me 10

‘mourn! [a sixty-two-yearold woman]

Acceptance of death can come only after a

full experience of mourning that may last many

months or even years.

My daughter died almost forty years ago, when she was

ten. Um still angry, and [still miss her. But for years after

she died I couldn't quite believe that it had really hap

pened—I kept thinking I heard her in the house, Now 1

ean accept what happened, even if I dont like it. (a sev:

centy-eight-year-old woman}

My husband died eighteen years ago and even though

today 1 have « happy; full if, I still miss him. Lam often

reminded of what he is missing, especially at happy

moments, such as the children’s high school and college

graduations, which are tinged with the wish that he were

alive o share the joy. (afifty-four-year old woman}

Mentalhealth experts have observed that

“troubled mourning’ can be a principal reason

for unhappiness and problems later in life

Mourning can go wrong in a variety of ways. We

may be unable to grieve at the time of loss, feel-

ing too numb to cry or to express our feelings in

any way at all. We may begin to grieve but cut the

process short, because of pressure to appear self-

possessed for a job or family or friends. Or we

may suppress our grief, drive it underground, in

which case it is likely’ to erupt again, perhaps

with surprising intensity, at the time of some

later loss.

In these cases, we may try to protect our-

selves from the pain of grief by adopting a self-

protecting mask of composure that allows us to

carry on with life as usual. Sometimes a physical

illness may appear, or self-destructive behavior

such as drug or alcohol addiction, an eating dis-

order, or repeated involvements in unsatisfac-

tory relationships. One or more aspects of

mourning can become exaggerated. We may

dwell on guilt, self-blame, anger, anxiety, or sad-

ness until we become completely incapacitated

and such feelings take the place of grieving.

In each of the above cases, the underlying

problem is that the person who mourns has i

some way not completed the mourning process.

416

i

i

we

Ste ctegt

© ARIE NAR

+ DeaTH AND Dvinc +

‘Sometimes friends or relatives, in a misguided

desire to be helpful, urge us to “get on with it,”

when in fact what we need is to honor the

urgency and depth of our feelings for as long as

we need to do so. Payiug attention to our feelings

and talking about them with friends or relatives

is extremely important.

When my husband was dying people helped us so much:

They came o visit aed brought food so that I could spend

‘more time with him. They gave flowers and hugs, gave the

children extra attention. Some people were too frightened

to visit and I understood. But the friend who came fifcen

‘hundred miles to see him before he died, the friend who

came five hundred miles to hold my hand during the

funeral, and the fiend who stayed atthe cemetery to cover

bis grave after the service will forever have my gratitude

Twas comforted by the notes and cards people sent

‘me. I read theme over and over again for many months,

nurtured by the care, sympathy, and support they pro-

Vided. Best of all were the handwriten notes that

included something about the writer’ relationship with

‘my husband or memories of times together—sometimes

things rhat were new to me, received notes from people I

had not known and was strengthened by their considera-

tion. Even the printed cards and the simplest notes indi-

cating that someone was thinking of me comforted me.

Nineteen years later, I still have all tke messages in a box

s0 our now grown children can share with their children

how the grandfather they will never know touched the

lives of so many others. (a ffty-four-year-old woman)

When my husband died it was like 1 was paralyzed

socially or months after. My two good friends did me a

(great service just by sitting with me. Sometimes T would

‘ery and sometimes I'd just be angry. Sometimes Iwas so

sad I could hardly talk. They'd come over to visit me at

least ice a week, and they stayed with it for more than a

‘year. When I felt better I could be a good friend to them

‘again. (a sixty-four-year-old woman]

earned a lot about anger after my mother died. Some-

how, when Iwas mouming, lots of anger came out that

didnt know was in me. My daughter suggested beating @

pillow witha stick 0 get the anger out, and finaly 1 g0¢ 0

Teould tall with my husband and also with my daughter

about some of the reasons why felt so much anger at my

oor mother. fa forty-three-year-old wornan}

Observing religious andior cultural tradi-

tions, writing about our feelings in a journal,

talking to family and friends, meditating, read-

ing poetry, watching emotion evoking movies or

plays, and singing or listening to familiar songs

canall help us feel our grief as deeply and fully as

we need. Joining a self-help group of people who

are grieving, such as a widow-to-widow group or

a hospice group, can be a great comfort. Such

groups help us realize that what we are feeling is

“normal” and is shaved by others.

ne same of as i ws get professional

rel rom a clergyman, for example, or per-

haps from a bereavement counselor—to deal

‘with the process of mourning.

1 functioned extremely well most of the time (everyone

always said how well), but I felt like I was just going

through the motions, waiting for my husband to come

home. Three times in the past four years I've arrived at

the point where I felt a need for counseling. Each time

Tve learned more about myself. The counseling has

helped me grow and find new meaning in my life. [a

‘woman in her fifties)

The loss of a child or grandchild can be par-

ticularly painful. If death is caused by a sudden,

unexpected accident that allows little or no time

beforehand for preparation, as is often the case

when someone we love dies young, the loss may

be even more difficult to come to terms with. We

cannot comfort ourselves by saying, “Well, she’s

lived a long and full life and it was her time to

die,” Even if we lose a child in her or his middle

How To HELP A DYING oR

RECENTLY BEREAVED PERSON

‘Give them the time and quiet listening to

express their feelings. Express your own

sadiness and regret, but do not presume to

tell a bereaved or dying person that a

death is “for the best,” even if after a long

illness. We don't really know how some-

‘one feels unless she or he tells us.

* Offer distractions, other topics of mutual

interest, but be comfortable with silence

and resist the need to fill every minute

swith words. Your very presence will help,

Take care of a dying or bereaved person;

do not expect her or him to take care of

you. Bring food if you visit someone's

home.

‘Offer help, and be specific in your sugge:

tions. Say, “I have two hours free on Sat-

urday. Do you want me to shop for you, or

is there something else I can do that

‘would be helpful?”

417

+ THe New Oursetves, Growine OLDER +

or late years, we may feel a sense of unfairness,

as if the natural order of things has been vio-

lated. This was not a loss we expected to sustain.

Losing my only daughter to AIDS was the hardest, most

hheartbreaking thing that has ever happened in my life, 1

kept trying 10 make sense of it. I couldn’ get over my

‘guilt. Why did I have to get sick? Why didi’ I make her

Stay where she was instead of coming here to take care of

‘me? Who would have known that she would fallin love

with « man who would give her AIDS? He shot between

hhis tes and hidden places on his body so she wouldn't

notice the tracks, Only my faith in God and the help of my

therapist carried me through my anger, mty guilt, and

wanting to die myself. Finally, ! was able to accept her

death and to cherish the happy years we had before she

passed on. (asixty-nine-yeat-old woman]

‘When death is expected, not only the

who is dying but also those who expect to be sur-

vvivors have time to make some preparations, get

relationships and business affairs in order, and

reminisce and say good-bye.

My father died of a heart attack and my mother died of

‘cancer My father’ death was a surprise and a shock, and

‘my mother’ death was a long ordeal. ! know that people

sometimes think thar sudden and quick death is east,

drut for me is was importzet to talk with my mother and

‘even jst 10 sit and hold her hand, and though those lat

‘weeks and months were hard Y'm grateful we had them,

With my father there was no time to ay good-bye. I wish

there had been. (a forty-nine-yearold women]

When we are faced with the shock of a sud.

den, unexpected death, we often console our.

selves with the knowiedge that the person we

loved did not suffer. While having time to pre-

pare for a death may be easier on our survivors,

‘many of us would choose an unanticipated and

painless death for ourselves.

When death comes at the end of a prolonged

and chronic illness, our feelings may take longer

to sort out. We may have already grieved, years

ago, for the loss of the whole, well person we

used to know.

My sister developed the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s

when she was sixty-two. [took care of her, moved into

her apartment for five years so she could stay in familiar

surroundings. Then Thad to put her into a nursing home,

‘where [visited her twice a week. I never missed a week

for nine more years until she died. There was very litte

‘that anybody could do for her. It was very hard to see her

‘become just a thin litle curled-up ball in her bed. For the

last seven years she didn’ recognize me or even talk at all.

‘She was my ony siser, and it was torribly sad for me. [a

sixty-two-year-old woman}

We may feel a sense of release for ourselves

and forthe person who died after prolonged su

fering. But later, intense, renewed feelings of loss

may surface.

Even though I thought Ihad prepared myself mentally for

the inevitable, I found I was terribly shocked, even sur

prised, when my mother finally did die. ! understand now

that shock after a death is common among those elose to

‘person, even when the death was expected.*

‘COMING TO TERMS WITH OUR

‘OWN DEATHS:

One of the important developmental tasks of the

second half of life is coming to a personal under-

standing, perhaps even an acceptance, of death.

Some of us continue to feel ambivalent and

scared about acknowledging death.

418

+ DEATH AND DyINo +

of my fiends have died young. We all knew each

for so long. (We had a card-playing group.) Three of

were my age. One of them I met recently and recog.

er name from elementary school, and so we were

same age. Another one was a few. months older sa we

bere all inthe sume age bracket. Now my sister in-law

died and she was only sixty-three. This has been on

ny mind so much lates, you know, reaching this point

t people my age are starting o go. I never used fo think

f these things before, Like if an aunt or an uncle died

f8 one thing, but now its cousins! One cousin my

died this summer, s0 I start to think “Its our turn”

ally, I'm very glib about it, but in my gut J cant

Eaccept that one day I wont be here, [a seventy-fouryear

Mold woman)

Maybe no one can ever be fully “ready” for

death in the sense of knowing about and fully

fPaccepting the experience in advance. But we can

RE prepare ourselves in a variety of ways.*

5. I feel a greater awareness of a mystery and. beauty in life

BP since Ihave accepted death as a personal eventuality for

pe. I dont rememiber exactly when that awareness came,

bi: Before then, Ihad thought of death “out there,” and now I

E friow that one day it wil be a reality for me. Eventually I

jam going (0 die. In a way, that has released me for more

‘vid living, (a seventy-cight-yearold woman]

g: ve dealt with losing loved ones many times in my life

fond after seventy years of repetition ofthat experience of

Ey wrief I find the thing that’s so hard to deal with is that

«Some person who has been a reality in your life no longer

“ists. When you're a kid, you learn how to separate fan.

f#asy front reality. But ther, when you get older, you have

Bo learn how to let goof a reality that person no longer

exists. I've got @ handle on that from years of experience

with it. So I no longer worry about my own personal

death, (a seventy-three-year-old woman}

Some of us are comforted by religious, spiri-

tual, or humanistic beliefs about life and death.

believe that tam not just a body which is perishable but

Lam a spirit which is eternal | believe that death is ony

an exit from this temporary life of unreality into a glori-

ous new life of reality. I hope, therefore, that there will Be

only rejoicing, not grief, at the time of my release. I am

ying to avoid being “earthbound” hy releasing my

attachments to material objects and persons before 1

‘enter this transition. [a ninety-two-year-old woman]

What I've been aware of lately because of a number of

instances of my being thrown up against death is that 1

shave a different perception of relationships. Death is not

@ termination of my life because my influence will con

tinue until the last person who knew me has died. [a

‘woman in her fifties]

Living each moment as fully as possible is

probably the most important way to help our-

selves become less fearful of death.

Ido not look to the future with dread. 11 has to be shorter

than my past but it does not have 10 be less rich. 'm more

relaxed. Idon' try 0 do everything.

That means I can take time for quiet, for meditation,

alternate this with activity, and see how I can keep a

moving, living balance between the two, [a seventy

eight-year-old woman}

Death, I am leamting through my own experience, need

not be frightening. After all, we are all bor terminal

cases, because we will all die, at one time or another,

Deaths is part of life. F have lived life fully and enjoyed it

greatly, which makes it easier to consider bowing out

than ifyou fel that you have missed out on alot.*

Providing support to others can also help us

come to terms with death. We can serve as

resources for one another and create supportive

networks that give us the strength and compan-

ionship we need to get through hard times.

On the day before her jifcy-cighth birthday, my friend

Maggy Krebs died m a Boston hospital. Magay was a femn-

“Tich Sommers, age seventy, ina eter to members of the

Older Women League about her expected death. Teh

founded and led the Sventy-treeshoutand member orga

Nanton after her eancer as dagnosed

419

4+ THE New OURSELVES, GrowiNe OLDER +

inist artist. Her humor, her drawings and paintings, and

her music had filed many lives with joy. Because I

believe that the final months of her life and her death were

‘models forall independent women. 1 want to tell vou part

ofthe story.

For months, Maggy gathered around her a group of

her friends, who tended to her at her home and atthe hos-

ital, In addition to caring for Maggy, we met each other

regularly, often weekly to share our grief and anger atthe

‘anticipated loss of a friend, to find ways to share the

responsibilty of taking care of her and to support one

‘another. We became a family for Maggy and for each

other.

‘One of Magay’s legacies to us isthe pride we fel that

we were able to give her the comfort and love she needed,

But Magey also left a legacy of hope to all women who feel

themselves to be alone by teaching us that we can sup-

port each other through the depths of ines, eshaustion,

fearand oss.*

Sharing the responsibility as this women’s

group did avoids the guilt women sometimes feel

when they cant do everything by themselves, An

illness support group allows each woman to pat

ticipate to the extent she is able to do so.

‘Some Day Tans Fuesit

Some day some atom of tis flesh shall be

commingled with a tree,

Will taste the resinous sap spicing its veins;

Wrestle with tempests; dance with silver rains:

And stand a singing tower against the sky.

My lapping blood existence will partake

with some far; hill-giet lake,

will cherish waterlilies on its flood;

Will shadow winging bird and dreaming cloud;

And hold the evening star within its cup.

Thave so joyed in campfire’s comradeship;

Have felt such grip

of awed delight at dogwood's miracle;

Such rapture in the living slope of hill;

Surely [shall be fire and flower and grass!

Fear? Fear transfiguration glad as this?

Such loveliness?

With these I have so loved, to be enfurled,

inwoven inall the beauty of the world?

ethaps—who knows?—My very heart shall be

for one mad hour of flaming ecstasy

sunset!

Plorence Luscomb

*Sce pages 192 and 206 forcartoons by Maggy Krebs.

In the last four years I have come from the

despair to festing that life is good and that ther stil iat

reason and a need for me to bein this world. Helping

train haspice volunteers continues to Be therapeutic ig

te, With the deat of my shad, things which on

read about in books or heard others talk about becant

very real and personal to me. Much of my own grief work

‘was done with the volunteer training classes, where the

volunteers gave me the opportunity 10 talk about my

experiences and my life, and the aloneness I felt atthe

fos of ny et frend end companion [a woman a

her fifties

Most of my friends are gone. You just have to say toyour-

self that it's something that’ going to happen. But is not

easy. It helps to do all you ean for your friends while

they reliving. {do alot of ealling onthe telephone. Ihave

4a friend [call every day. He's been in the hospital along

time. Thave another friend who lives down in another

town who's quite sick that I call at least once a week.

Death used to be scary (0 me. Four or five years ago, if

thought of dying, 1d push it out of my mind. But now,

think, after al, ve lived out my days and I keow I've got

togo. {a woman in her eighties]

Florence Luscomb, sufjragist labor organizer,

‘ivilrights and peace activist, Died in 1985 at age

nninety-eight Elen Stab

420

+ DEATH AND DytNo +

‘Another way to prepare ourselves for dying is

care of any unfinished business in our

ss. Most of us have unresolved relationships—

ne that go back quite far—that we may want

gp work out or perhaps just make a final state-

int on. We can seek out people with whom we

ive unfinished business and see to it that some

unforgiven hurts are healed—and recognize

some can't ever be healed. Those who have

de the effort to do this say tis very important.

efore her death my sister asked to see each of her five

thers and sisters. We talked about the ways we had

en close and trusting with each other, and we also

tlked about some of our long-standing fights and

dges. I know thatthe hour that she and I spent going

dr our times together was very important to me. [twas

‘way to say good-bye. And I think it was important

healing for her, as well. [a forty-seven-yearold

oman)

Ej:tcan remember the day my grandfather died, in a tractor

‘accident on the farm. The men brought him in from the

field to the house, and my grandmother, my mother, and

‘my aunt bathed and dressed him. I was a loving act, and

f ritual, and J was terribly impressed. I was eight at the

time, My own father went from the hospital bed where he

F< died to a funeral kome, and I know my mother doestt?

feel like she was a part of his dying. I'm tying 10 wnder-

stand that difference, and what I myself want to do in

‘that regard. fa sixty-seven-yearold woman}

In some cultures, death is understood to be a

natural transition at the end oflife. Among some

Native American tribes, for instance, each life is

seen as a road that is expected to come to an end,

The healers in those societies see themselves as

“keepers of the road,” guardians of health for as

& Jong as the journey goes on—not as persons who

‘work to prevent the journey from ending in its

‘expected transition,

But in our contemporary culture, we invest

j heavily in science and want to believe that

through it we can control all the events of our

lives. We have hope that the discoveries of science

will allow us to prolong life and prevent “death,

These attitudes make it hard to look on death as

the natural, expected end of life, and make it

harder to accept the inevitability of death.

Physicians often use every possible means to

protong life without regard for its quality. The

result can be feelings of anguish and heipless-

ness on the part of the dying person, relatives,

and friends.

When my husband had his heart attack I thought 1

should rush him to the hospital. The ambulance came

right away but by the time they resuscitated him he

already had a lot of brain damage, He never recovered

consciousness. Everyone in the ICU [Intensive Care

Unit] worked very hard to save his life, and he did live for

‘another two weeks, but as faras I'm concemed he wasn't

realy alive—just a body attached to a lot of tubes and

machinery. Lwish now that Thad just held him, cradled

his head, when he first fell! could have said good-bye

that way. [a sixty-five-year-old woman]

As some medical professionals are beginning

to recognize, focus on the inappropriate pursuit

of a cure when the situation is clearly beyond

hope can lead medical personnel to make a per-

son's last days more painful and difficult than

necessary. Of course, there are situations of

acute emergency in which one cannot be sure

whether recovery is possible; it is very hard to

know the right thing to do in such a case. But

some medical treatments designed to cure, such

as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, may increase

the dying person's discomfort.

‘Many of us may feel more secure in a hospi-

tal when we are very ill. Or we may feel we want

to try, or should continue to try, medical reme-

dies on the chance that one may heal us.

My daughter died of breast cancer at age foty-swo. We

‘thought she wanted to deat home and we were ready to

‘ake care of her there. But inthe end the doctors urged her

to try one more round of treatment with chemotherapy

‘and she went back into the hospital. She never came

hhome again, and forthe fast week she was so sick and in

such pain tha she di even ware her teenage children

‘als her [a snty-efght-year-old woman]

Discomforts such as pain, shortness of

breath, weakness, nausea, and vomiting often

precede death. The last days of living can be

eased by concentrating on comfort rather than

eure. (See Dealing with Pain in the chapter

aan

+ THe New Ourseives, Growine OLDER +

Habits Worth Changing, pages 35-36.) Occa-

sionally, treatments such as radiotherapy or even

surgery may be used to bring relief of pain and

discomfort, though it is more common to use

high doses of pain-relieving drugs.

We were lucky enough to find a doctor who was willing 10

come to the house and could prescribe drugs for Grand-

rma’s pain and also for the nausea. We heard about the

doctor because she had performed the same service for a

neighbor down the street, and she made a hard time

‘much easier than it might have been. (a thirty-six-year-

‘ld woman]

‘TAKING CONTROL OF OUR

OWN DEATHS

Many of us would prefer not to be subjected to

machines and tubes and complex technological

procedures that may extend life a few extra days,

weeks, or months at the expense of whatever

quality it may be possible to achieve. Some of us

who have such thoughts, however, will surely die

in the very circumstances we deplore. How does

this happen?

‘We tend to forget experiences that most of us

have had as patients, like being moved from one

treatment to another with little explanation of

what is really thought to be wrong, how the

treatment is supposed to work, and what to

expect next, as if once we become patients we

have given over the right or desire to make

choices. The physician often doesn't present

alternatives from which we can choose; the alter-

natives of no treatment or of treatments such as

acupuncture or herbal remedies are rarely dis-

cussed. This failure to present alternatives

makes it difficult for the ill person to make

informed decisions. Being a patient can feel like

‘being ona slippery slide you cant easily get off.

My daughter spent the last months of he life going tothe

hospital for outpatient treatments, and feeling terrible.

wortt ever do that, Tm not saying it’s any better to be sick

{rom the cancer, but at least you'd fel like its your bod

dnd your life. Ti want to have some tne to myself live

ait fT thought f was going to die soon. (a ifty-nine-

yearold woman] :

Here are some things to remember about

doctors and dying:

* Physicians cannot actually predict recovery,

death, or future disability for any single

; they can only make broad, educated

guesses based on statistics for large popula.

tions. They deal in group probabilities.”

* Many people whose death was predicted with

firm certainty by medical experts have recov-

ered: this happens with sufficient regularity to

remind us that iliness is not fully understood

byscience.

+ Each individual has a right to say how she or

he will live out the last days of a soon-to-be.

ended life. If living outside a hospital or with-

out the discomfort of medical treatment is

what you want, your right to do so ought to be

honored.

Ten years ago, when 1 was fortyfive, I was told I had

breast cancer. For the next year I had chemotherapy and

radiation—I was sick and worried the whole year. But

now I feel that when the cancer comes back I just want to

live with it, except for painkillers when I need them. 1 feel

that ifm going olive on, or die, I want to be able to expe-

rience each day as my day. I've written letters (0 each of

‘my children to let them know how important this is ome.

Even when we try to stay in control, an ill-

ness can become overwhelming and may deplete

our energy reserves, especially if we do not have

a dependable support system. Though we may

aspire to a serene death for ourselves or a loved

one, surrounded by familiar faces, we must rec-

‘ognize that humans have never been able to con-

twolor predict death.

I felt like I was in a dream. had promised my husband

wouldnt send him back to the hospital, but I was up for

twenty hours each day taking care of him and I just

‘couldnt go on. He agreed to go back because I promised

him that I would live there with him. The last ten days he

didn’ talk but he seemed t0 be comfortable. They were

giving him morphine intravenously. The doctor woke me

at 3 Ast 10 tell me he had died while I was sleeping. It

bothered me that 1 was sleeping when he died because 1

+had promised him that Twould be with him. Idon’ know

if he would have said anything if 1 had been awake. No

‘matter how hard you try, it doesn? always work out the

‘way you want, (a woman in her sixties)

Advance Medical Directives

IE you ‘decide thlatiin some circumstances you

‘would prefer to have no treatment, or treatment

for comfort only, you have a right to refuse treat-

ment. In every state, constitutional and common

Jaw support the right of any competent adult to

refuse medical treatment in any situation.* How-

ever, writing your wishes in an advance medical

422

Girective can protect your right to refuse treat-

Bent, make it clear to your family members and

Pealth-care providers what you want, and help

em to comply with your wishes,

» Anew federal law requires hospitals, nursing

nes, HMOs, and home health agencies serv

g persons covered by Medicaid or Medicare to

de Information ‘upon admission about

directives and to explain your legal

and choices. If they will not honor your

they must tell you, so that you can select

er institution. State laws vary on this, and

have provisions for doctors who, for rea-

of conscience, will not comply with certain

es. Check with your state attorney generals

They may be able to provide you with

‘ate forms as well.

‘Advance medical directives can be stated ina

ng will or in a durable power of attorney for

alth care. In a living will you give directions

‘your future medical care, stating what you

fant and don't want. A durable power of attor-

éy for health care is a document in which you

‘Appoint a health-care agent or proxy to represent

pu in the event you become unable to commu

te your wishes. If possible, discuss your

‘with your health-care proxy or represen-

and give her or him copies of all relevant

iments,

‘As of June 1993, all fifty states and the Dis-

trict of Columbia authorize either living wills or

B the appointment of a health-care agent. Three

, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New York,

paiithorize only the appointment of a health-care

gent, and two states, Alabama and Alaska, a

B thorize only living wills?

F Living wills are valid only in cases of termi-

pal illness—that is, when a person is expected to

lic in the near future, usually within six months,

a direct consequence of injury or illness. They

‘not honored in situations when a person has

slow degenerative disease or when a very old

firson has “muliplo systems flue” In these

ations, appointing a health-care proxy throug!

durable power of attorney may be more effec-

> Another drawback of the living will is that it

: Operates primarily for treatment refusal. If you

{Want all possible treatments tried, a durable

Bower of attorney is more useful” and may serve

for treatment refusal aswel, a

Assuring that you get adequate medical treat-

E ment if you are severely ill may take more than

‘writing out your wishes. The cost-containment

‘emphasis in medical care has resulted in people

F

+ DEATH AND Dyine +

being discharged from hospitals when they still

hope for recovery and want treatment. Older

persons, especially those with limited funds, are

at-an especially high risk of being discharged

prematurely agains: their wishes.

Dying at Home

At one time, almost everybody could have

expected to die in their own homes—even in

their own beds. Now, death more often occurs in

a hospital or nursing home. Recently, however,

"pore people are insisting that they be allowed t0

die outside of these institutions.

Idon' want anyone to tell me what to do. I ived all these

‘years with my eight children, and made decisions, right

orvsrong, about how we'd live. I want to decide for myself

now: I've no need for medicine, drugs, or hospitals, never

have, and 1 don't want to start now. I want to die with

dignity. I'm comfortable in my home among my own

‘things and with my family around me. They'l care for

‘me. They" respect my wishes. Ican see who [want in my

‘own home. Ican eat what I want to eat. know my own

body and what it needs or can handle. Iv a private per-

son. There's no privacy in the hospital. I want my chit-

dren around me. 1 need their touch, their love. [a

seventy.six-year-old woman}

‘Mom needed to be hostess and be in charge in her home

even while dying. She continued to direct and guide her

children about her care. While we held a cup to her

‘mouth, she would urge, “Eat with me.” When she needed

‘more care, we hired hospice workers. When I introduced

my mom to the new worker, Mom was already in her

“withdrawal from the world stage." But she drew herself

‘together from her fetal position under the blankets to peek

at this new person, and, in her weak, raspy voice, said,

“Welcome to my home.” These were her final words to the

world. What a magnificens, feisty, independent woman

this mother of mine was. She showed us how to live and

‘how to die. Mom passed on as peacefully as possible con-

sidering her pain and weakness. [a filty-seven-yearold

woman, the daughter of the wornan quoted above]

A.woman who is a midwife wrote the follow-

ing account of her mother’s death:

‘This past year brotight serious illness to my mother, Mar-

ion Cunningham. We sought conventional medical

attention, plus an array of alternative healing practition-

ers. Afier months of misdiagnosis, Marion diagnosed her-

self as dying. We admitted her to the hospital and, alas,

the diagnosis of lung cancer was finally acknowledged.

My brother, my sister, and I stood in disbelief at her side,

423

+ THe New OURSELVES, GRowiNe OLDER +

Marion Cunningham Roxanne Cummings Pore

A pioneer in natural childbirth and in single parenting,

she had always been our source of strength and inspira-

tion. Weall ried together that day. Then Marion spoke to

ime, words which would affect our caring of one another

in the months to follow: "Why dont they have midwives

for what I've got?” We decided tocar for her at home.

‘One night at midnight 1 received a call from my

brother... "Mom says she will die today and that you all

should come.”

dnd thus i was thar we gathered round. My brother

requested that I sing “The Goodbye Song,” which I had

‘written just a month before.

th see you in the babies’ faces

I feel you in the wind

hear you in the quietest places

Tihold you in my friend.

I played on my guitar and sang to Marion, and in the

hnidst of the song I could hear her breaching relax and

knew she would die. We watched one tear roll down her

face and then she took her last breath."

Hospices

A relatively new institution called the hospice

hhas developed in response to the growing inter-

est in dying at home. The hospice is modeled

after medieval way stations that accommodated

both travelers and those who were dying (death

being, metaphorically, another forni of travel).

‘Contemporary hospice agencies started out

as coalitions of volunteers who were trained to

visit and offer help to dying people in their own

homes. Most hospice agencies now also have

specially designed inpatient buildings where

people can get short-term help managing un-

comfortable symptoms and then go back hor

‘The services of medical professionals are a rele.

tively minor part of the care offered by hospices,

‘They also provide trained volunteer visitor, vis:

ing nurses, nurses” aides, homemakers, and

bereavement counseling for family and frends,

‘One of the major goals of a hospice program

is to maintain the quality of life through spiritual

and emotional support, medication, and meth-

fds such as meditation and visualization for

pain control. They will also provide temporary

relief for caregivers.

(Our son died of Hodgkin's disease two years ago. Toward

the end he said he didn't want to go back into the hospi-

tal, no matter what. We called the hospice and they sent a

volunteer who came to vist John two days a week a frst

and then, at the end, every day. He was almost like a

‘member ofthe family, and the help he gave made a bi df-

ference to all of us—especially 10 Jolin [a seventy-six-

year-old woman}

Some of these services have always been

available from visiting-nurse and home-care

agencies, clergy, church-visitation committees,

and other local sources. But a hospice program

coordinates all these services. Medicare, Medic-

aid, and some other insurance plans may pay

part of the bill. Not all communities have hos-

pice agencies, however. If you want to locate the

hospice nearest you, call a visiting-nurse agency

or a local hospital's social service department.

(See Resources for this chapter for the two

national hospice organizations.) A local Social

Security office can also tell you which hospice

programs are Medicare certified.

Choosing the Time of Our Death

Two years ago my mother, who was then eighty-three, told

‘me that she planned to end her life by taking an overdose

of pills. Her health was failing rapidly and she was going

blind. She didn't want to become weak and dependent.

She had always been a fierce and active woman, She

wrote her intentions ia fetter to me—I was her only close

family member—and she told two friends and her doctor.

We all cold her that we would not help her accumulate

enough pills do the job. And I think we all worked very

‘hard to help her find new reasons 16 be happy to be alive.

But finally I understood that she really wanted to do what

she had planned. and in the end, offer she gathered

together enough pills and took them, sat with her for the

last thrtysix hours as she slipped away, I cant tell you

show many of her friends and acquaintances told me how

‘graceful my mother was it her life to the very end. For my

424

+ DEATH AND Dytne +

‘mother, given her personality, staying in control of her

own life made her graceful. [a forty-one-yearold woman]

There is a great difference between someone,

terminally ill and in pain, who says, “Tve lived 4

j Gull, long life and I think this is may time to die,”

, and someone who is viewing life through the fog

(of depression and says, “Idon't want to go on Ine

eR mS der ogame,

ing.” For a depressed person, a suicide attempt

fy may be a call for help in finding resources 10

p Tegain pleasure in living. You can get help for

such a person through a suicide-prevention

p organization like the Samaritans (see Resources

for this chapter),

tis very difficult to know what to do when a

cone wants to end her or his life. Talking

with this person can help us distinguish tempo-

rary feelings of discouragement from the convie-

tion that a life of pain and deterioration would

be unbearable,

Laws vary from state to state, but nearly

everywhere, a person who helps a dying family

member or friend commit suicide risks prosecu-

tion as an accessory to a crime. To protect their

loved ones, some dying persons have chosen t0

g0 off by themselves and take a fatal substance.

They have had to do without the loving support

and the talking and planning that would have

eased the transition for everybody.

Claiming the right to control the end of our

lives in no way minimizes the seriousness or the

finality of the decision, nor the pain and grief of

those we leave behind. A number of organiza-

tions, such as Choice In Dying, now publicize

issues and can help us deal with them per-

sonally (see Resources for this chapter)

Practical Matters

Before we die, some of us may want to arrange to

donate vitally needed organs, such as kidneys

and corneas, for transplant Purposes, We can

also plan the kind of funeral or memorial service

‘we want. Helpful, practical information on these

matters is available from the Older Womens

League as part of their “Living Will Packet” (see

Resgurossforthis chap a

A growing number of people today want to

keep ‘matters relating to death under the control

of the ic i

‘mation itself, and last rites and memorial ser-

vices can all, within broad limits, be designed to

suit the wishes of the person who has died and

her or his survivors.

The person I talked ro about renting a place forthe memo-

rial service told me sharply that I had no business plan

fring a memorial while my mother was stillalive. But lam

ery thant thas we did plan it when we did. First of all,

as amazed fied thaeFwasin absolutely mo condbeon

‘0 make sensible plans after she ded... Planning the

forms of the memorial beforehand helped mie face the real,

{ty of my mothers death. Thinking about and writing

what ! would say brought the love we had shared back

‘me once more. Petcipating in the memorial gave me a

ind of peace and acceptance t hardly dared hope for!™

If you have preferences about your burial, it

will be much easier for your family and friends

to carry out your wishes if

known ‘in writing. This will also Protect your

loved ones from having feelings of guilt, because

they will be assured they ate following your

wishes,

Remember that the funeral business is just

that-—a profitable business, There are some reg.

ulations, from state to state, that govern

this industry. You can leam about them by call-

ing your state attorney general’ office.

1 foundout later thatthe funeral director lied to me when

the said stare law required a cement lining for my hus.

bands grave, contrary to our personal and religious

belief. [a fifty-ive-year-old woman}

Those of us who are struggling to come to a

better understanding ofthe great, universal ran.

sition at the end of life have many opportunities

to ponder the matter: Experiences such as watch.

ing persons we are close to approach death, be.

‘coming aware of symptoms that might signal the

inning of life-threatening ilIness putting ne

affairs in order in a written will, working as avo.

unter in a hospice agency, or being part of a

‘supportive network for a dying friend or relative,

all can help us come to a peaceful, personal un.

derstanding of death.

Notes

1. Tish Sommers, Death—A Feminist View, Paper

presented at Drake Uuiversity Law School, Des Moines,

Towa. March 271976, *

2, Phyllis R. Silverman, Helping Women Cope with

Gri Bere i: Saget

3. Carolyn Ruth Swift unpublished manuscript

4 Sty Spencer lag Read Broom Vl 7,

‘No.6 (November-Decamber 1988), pp. 40-42,

5.3. W. Wordes and Willam Proctor, Personal Death

Awareness. Englewood Clifs, I: Prentice Hall, 1976

425

+ THe New Ourseives, Growinc O1pen +

6. Swift, op.cit.

7. See Stephen Jay Gould, “The Median Isn't the

Message.” Discover, Vol. 6, No.6 une 1985), pp, 40-42.

8. George Annas and Joan Dennsberger, "Compe-

tence to Refuse Medical Treatment: Autonomy vs. Pater

‘alistn.” University of Toledo Law Review, Vol. 15 (1988),

p. 561-96,

9. Choice in Dying, Inc., (see Resources for this

chapter), State Statutes Govemiing Living Wills and

Appointment of Health Care Agents, June 1993,

10. Barbara Mishkin, ‘Making Decisions for the Ter.

‘minally IL” Business and Health, ne 1985, pp. 13-16.

41. Roxanne Curamings Potter, “To Lite—To Death.”

alfornia Association of Midwives Newsletter. Syeing

1984, p.7.

12, Spencer, op.clt.

426

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Some Reflections On Violence Against Women by Radhika Coomaraswamy IndiaDocument5 pagesSome Reflections On Violence Against Women by Radhika Coomaraswamy IndiaVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Case List (KK Luthara Memorial Moot Court Competition) Memo For DianaDocument1 pageCase List (KK Luthara Memorial Moot Court Competition) Memo For DianaVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- CH 4 Adolescence Change VulnerabilityDocument28 pagesCH 4 Adolescence Change VulnerabilityVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Subordination and Sexual Control A Comparative View of The Control of Women by Gita SenDocument6 pagesSubordination and Sexual Control A Comparative View of The Control of Women by Gita SenVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Refugee Definitions Source: United States Association For UNHCRDocument2 pagesRefugee Definitions Source: United States Association For UNHCRVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Sumangala's Mother, India, Pali Language, 13 CenturyDocument27 pagesSumangala's Mother, India, Pali Language, 13 CenturyVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Yosano Akiko, "Labour Pains," Japan, 1878-1942Document30 pagesYosano Akiko, "Labour Pains," Japan, 1878-1942Vedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation: Key FactsDocument4 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation: Key FactsVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Mridushi FactsDocument1 pageMridushi FactsVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- In The Hon'Ble High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench, LucknowDocument12 pagesIn The Hon'Ble High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench, LucknowVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- In The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of IndiaDocument18 pagesIn The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of IndiaVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- SemIV - Labour. Arpit Parakh .33Document15 pagesSemIV - Labour. Arpit Parakh .33Vedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- In The Hon'Ble High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench, LucknowDocument12 pagesIn The Hon'Ble High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, Lucknow Bench, LucknowVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Legal Notice: Notice From The Buyer To The VendorDocument7 pagesLegal Notice: Notice From The Buyer To The VendorVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

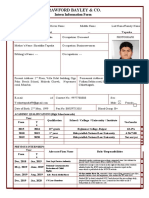

- Crawford Bayley & Co.: Intern Information FormDocument2 pagesCrawford Bayley & Co.: Intern Information FormVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Consumer PlaintDocument5 pagesConsumer PlaintVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Bail Application U/S 438 Cr.P.C. For Grant of Anticipatory Bail On Behalf of The Accused (Mr. V)Document4 pagesBail Application U/S 438 Cr.P.C. For Grant of Anticipatory Bail On Behalf of The Accused (Mr. V)Vedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Assignment of IghtsDocument7 pagesAssignment of IghtsVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet