Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Human Nature and The Chain of Being

Uploaded by

Maria Mureșan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesOriginal Title

Human nature and the chain of being.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesHuman Nature and The Chain of Being

Uploaded by

Maria MureșanCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Beşliu Maria

Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Bucharest

English Literature

Seminar Tutor: Sorana Corneanu

Human nature and the chain of being – the paradoxical mode

The theme of human nature was a controversial debate subject for eighteen century

philosophers and writers. Broadly speaking, the dominating viewpoints were divided into two

chief categories. On the one hand, the first conception stemmed from the Biblical narrative of the

Adamic Fall, according to which the human nature became deeply corrupted by sin. In chapter

XII of his book, “Essays”, Michel de Montaigne provides his readers with a list of vices, among

which the cardinal sin is represented by pride, man’s arrogance of considering himself equal to

God, which, after all, was the sin that caused Lucifer’s fall much time before Adam’s. In relation

to this view comes the equally controversial theory of The Great Chain of Being, which

represents a famous concept approached by some of the greatest eighteen century writers, such

as Bolingbroke, Pope, Diderot and Kant, and rejected by others, such as Voltaire and Dr.

Johnson. The concept was primarily based on the idea that the universe is created in a perfect,

well-designed order, every species being continuously related to the other, a notion explained by

Locke. Some of the most prominent writers who embraced the “Fallen Nature” perspective were

thus Montaigne and also, Blaise Pascal, who presented it from a theological point of view. The

concept has echoes in Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope’s writings. On the other hand, the

opposite standpoint presented man as innately being endowed with qualities, with the power of

being good, a theory shared by writers such as David Hume, Samuel Johnson or Henry Fielding.

In what follows, I will approach this theme from the first perspective, presenting the

subject of human nature as depicted in some excerpts from Pascal’s work, Pensées. The writings

of the illustrious French Christian philosopher, mathematician and scientist included this

collection of notes published after his death under the title Pensées (Thoughts), representing his

most powerful theological apologetic work. Its aim was to defend the Christian faith by

combating the arguments of skepticism and stoicism. In addition, I will draw a parallel between

Pascal and Swift’s fundamental means of expressing their assumptions, with a focus on the

particular situation of Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels”, making an attempt to place Swift in one of

the two categories designed by Pascal, on the one hand, and Pope, on the other hand.

In the first selected excerpt (“Oppositions”), Pascal identifies man’s nature as fluctuating

between two major traits: lowliness and greatness, and he claims that man should be conscious

of both: “Man must not believe that he is equal either to the beasts or to angels, nor must he be

ignorant of either, but he must know both.” (Pascal, p.33) Speaking about man’s greatness and

wretchedness, he states that man’s greatness simply lays in the fact that he is aware of his

wretched nature: “In short, man knows he is wretched. (…) But he is truly great because he

knows it” (Pascal, p.33).

Furthermore, the author deals with the subject of man’s paradoxical nature and he makes

one of his most tremendous and well-known claims regarding man’s duality: “What a chimera

then is man! What a surprise, what a monster, what chaos, what a subject of contradiction, what

a prodigy! Judge of all things, weak earthworm; repository of truth, sink of uncertainty and

error; glory and garbage of the universe.” (Pascal, p. 36). Moreover, he provides a solution for

dealing with man’s puzzling nature, stating that truth is not something we mere mortals can

possess, but it is an attribute of God made known to us by Him only by revelation: “we can know

it only to the extent it pleases him to reveal it. Let us then learn our true nature from the

uncreated and incarnate truth”, his last words being a possible reference to Jesus Christ’s

assertion regarding Himself: “I am the way, the truth and the life” (John 14:6 NKJV), as well as

the introductory words in the Gospel of John: “the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us”

(John 1:14 NKJV). He continues by directly offering the solution: “Know then, proud man, what

a paradox you are to yourself. (…) Learn that man infinitely transcends man, and hear from

your Master your true condition, of which you are ignorant. Listen to God.” (Pascal, p.36)

In addition, Pascal claims that man’s awareness of his wretchedness is possible because

of the fact that he once fell from a higher position, logically deducting this in the following

manner: “if man had never been other than corrupt, he would have no idea of truth or bliss. But,

wretched as we are (…) we have an idea of happiness and cannot reach it. (…) Being incapable

of absolute ignorance and certain knowledge, it is obvious that we once had a degree of

perfection from which we have unhappily fallen” (Pascal, p.36-37). Moreover, he claims that

only by our awareness of the initial sin because of which man has fallen can we have a genuine

knowledge of ourselves. Then, he outlines the two main constants that describe human condition:

one of them is that in his initial position, “in the state of creation” (Pascal, p. 37), man was

ruling the nature, being above it and sharing God’s divinity. The other is that after he sinned and

fell, “in the state of corruption and sin” (Pascal, p. 37), man became “similar to the beasts”.

(Pascal, p. 37) However, after that, by His supreme sacrifice (the death of his Son, Jesus), God

provided man another “state of grace” (Pascal, p. 37), allowing him to share again the divine

nature, provided that he accepts Jesus and Pascal says: “Thus it seems clear that through grace

man is rendered similar to God, participating in his divinity, and that without grace he is

considered similar to the brute beasts” (Pascal, p. 38). Therefore, at the end of the chapter

“Diversion”, Pascal makes another tremendous assertion: “Knowledge of God without

knowledge of our wretchedness makes for pride. Knowledge of our wretchedness without

knowledge of God makes for despair. Knowledge of Jesus Christ is central, because in Him we

find both God and our wretchedness” (Pascal, p. 56)

In the next excerpt (“Transition from the Knowledge of Man to That of God”), the writer

deplores the atmosphere of uncertainty that seems to govern man’s life. He confesses that he is

“frightened” (Pascal, p. 57) at seeing how man is “lost in this corner of the universe, not

knowing who put him there, what he has come to do, what will become of him at death” (Pascal,

p. 57) and moreover, “these wretched souls look around and see some pleasant objects to which

they give themselves and become attached.” (Pascal, p. 58). Furthermore, the writer urges man to

consider carefully the nature surrounding him, the earth, the sky, the moon, the stars and then he

draws the conclusion regarding man’s position in universe: “For, in the end, what is man in

nature? A nothing compared to the infinite, an everything compared to the nothing, a midpoint

between nothing and everything” (Pascal, p. 59).

The author moves now to another important theme, that of man’s desire of knowledge.

He shares Montaigne’s view concerning man’s both vain and vainglorious attempt to attain

supreme knowledge: “It is strange that they have wanted to understand the principle of things

and in this way come to know everything, a presumption as infinite as their object” (Pascal, p.

60) He claims that only the infinite supreme Creator of all things has the supreme knowledge

about everything and we, as finite beings, simply do not have the capacity to grasp the infinite:

“All things come from nothingness and are swept towards the infinite. Who will follow these

astonishing proceedings? The author of these wonders understands them. No one else can.”

(Pascal, p. 60) In this respect, he criticizes writings of renowned authors, such as Pico della

Mirandola or Réné Descartes, entitled “Of Everything Knowable”, or “Of the Principles of

Philosophy”. He immediately draws the conclusion derived from his postulations, highlighting

man’s position in relation to the infinite: “Let us, then, understand our condition: we are

something and we are not everything. (…) The smallness of our being conceals from us the sight

of the infinite” (Pascal, p. 61).

Moreover, the author is also in favor of the fact that man should not try to get past his

condition, but we should remain “in the state where nature has placed us” (Pascal, p. 62). As far

as the problem of “The Great Chain of Being” is concerned, the writer states that “All things,

then, are caused and causing, supporting and dependent, mediate and immediate; and all

support one another in a natural, though imperceptible chain linking together things most

distant and different” (Pascal, p. 62)

In the end, Pascal draws three main important conclusions to his arguments: first and

foremost, “Man is only a reed, the weakest thing in nature, but he is a thinking reed.”, secondly,

“All our dignity consists, then, in thought,” and consequently, “Let us labor, then, to think well.

This is the principle of morality.” (Pascal, p. 64)

With respect to the means used by Pascal to convey his conception on the origin and

essence of human nature, one of the techniques he employs is the paradox. The passage that best

instantiate this method is the aforementioned one, the man as a “chimera”. Thus, we have in

front of us the image of man as a “monster”, if we take into account the etymology of “chimera”

(khímaira, female goat, or, as Greek mythology presents it, a monster with two heads, a lion

head and a goat head). In his first state, man was indeed master over nature, but in his corrupt

state, he has descended to the level of animals, dominated by his carnal desires. Also, in his

previous statement describing man equal neither to animals, nor to angels. Pascal could have had

in mind the Biblical passage taken from Psalms: “What is man that You are mindful of him, /

And the son of man that You visit him? / For You have made him a little lower than the angels, /

And You have crowned him with glory and honor. / You have made him to have dominion over

the works of Your hands; /You have put all things under his feet” (Psalms 8:4-6, NKJV), passage

also quoted in The New Testament, in Hebrews chapter 2 and interpreted as referring to Jesus

Christ. Further on, Pascal states: “Limited as we are in every respect, this condition of holding

the midpoint between two extremes is apparent in all our faculties” (Pascal, p. 61).

If one is now to make a comparison between Pascal’s means of conceiving and

explaining the human nature and Swift’s, one could notice that while Pascal employs paradox to

convey his assertions, Swift’s instrument is satire. What these methods have in common is that

both of them use antithesis as main figure of speech. Swift’s Gulliver comes into a world

dominated by Houyhnhnms, whose subjects, described in an antithetical way, are the Yahoos.

Pascal’s description of human being acquires a dualistic view – “glory”, as well as “garbage”.

The difference consists in the fact that while satire makes a clear distinction between the two

states it describes, each having its own characteristics, paradox may result in ambiguity, in an

instable perspective, a blurred image. Houyhnhnms and Yahoos are essentially separate in their

own nature, the“glory” and “garbage” reside, though, in one being. Also, satire uses irony to a

great extent so as to effectively convey the author’s view. Moreover, one clearly observes the

fideistic theological implications at Pascal, while these are missing at Swift. In addition, usually

satire conveys a clear moral message in the end, nevertheless, this does not seem to be the case

with “Gulliver’s Travels”. Although there are some similarities with Pope, the latter, however,

employs in his satires unequivocal antithesis, adopting some ideas from Pascal, but applying

them to a distinct system of thinking. “Pope’s satiric invectives are immediate responses to the

almost universal acrimony of early eighteenth-century cultural discourse, but they consistently

manage to outclass the often venomous provocations of his enemies, both real and imagined.

Pope’s poetry may be as splenetic as that of his rivals, but it has a range, a sophistication, an

energy, and a precise delicacy which is quite unmatched by that of any other poet of his time.”

(Sanders, 285). The splendid beauty of the renowned verses from the second epistle of Pope’s

“An Essay on Man” clearly reflect Pascal’s conception of human nature: “He hangs between; in

doubt to act, or rest, / In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast; / In doubt his mind or body to

prefer, / Born but to die, and reasoning but to err; / (…) Created half to rise, and half to fall; /

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all; / Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled: / The

glory, jest, and riddle of the world!” and one could even say that Pope transposed into verse

what Pascal had written in prose. Nevertheless, the notable difference between Pope and Pascal’s

solution to the finite nature of man is that while Pascal says that the only knowledge that saves

man is not knowledge of “our wretchedness”, but “knowledge of Jesus Christ”, the incarnate

truth, Pope claim that man should ultimately attempt to know himself: “Know then thyself,

presume not God to scan; / The proper study of mankind is Man” (The Norton Anthology of

English Literature, p. 2250, Epistle II, 1-2; 7-10;15-18).

Although the answer to the question regarding Swift’s position in the lines of thought

drawn by Pope, on the one hand, and by Pascal, on the other, is rather an ambiguous one, yet his

writings remain undoubtedly unique. As Andrew Sanders remarks, “His writings —

characterized throughout by a subtle ambiguity, by a troubled delight in oppositions and

reversals, and by a play with alternative voices, personae, and perspectives — are intimately

related to the deeply riven political, religious, and national issues of the Britain and Ireland of

his time.” (Sanders, p. 280-281).

In conclusion, after having presented Pascal’s viewpoint on human nature as falling into

the first type of perspective, the Augustinian one, or at Pascal, the paradoxical one, we have seen

that in his conception, man holds an intermediary place between the created beings, between

angels and animals and, moreover, after his fall into sin, he has even descended at the level of

animals. Therefore, the only solution for his wretched state is God’s grace: “through grace man

is rendered similar to God, participating in his divinity, and (…) without grace he is considered

similar to brute beasts” (Pascal, 38).

Bibliography

Pascal, Blaise, Pensées. Ed. Ariew, Roger, Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 2004

Lovejoy, Arthur O., The Great Chain of Being, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England:

Harvard University Press, 2001

Sanders, Andrew, The Short Oxford History of English Literature, Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1994

Abrams, M. H., The Northon Anthology of English Literature, volume I, New York: W.W.

Norton & Co., 1962

Bible Gateway. (2018). Bible Gateway passage: Psalm 8 - New King James Version. [online]

Available at: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm+8&version=NKJV

[Accessed 19 May 2018].

Bible Gateway. (2018). Bible Gateway passage: Hebrews 2 - New King James Version. [online]

Available at: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=hebrews+2&version=NKJV

[Accessed 19 May 2018].

En.wiktionary.org. (2018). chimera - Wiktionary. [online] Available at:

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/chimera [Accessed 19 May 2018].

En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Antithesis. [online] Available at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antithesis [Accessed 19 May 2018].

You might also like

- The American Dream and Slavery - EssayDocument5 pagesThe American Dream and Slavery - EssayMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Presentation Handout - The American Dream and SlaveryDocument5 pagesPresentation Handout - The American Dream and SlaveryMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- "Look Back in Anger" - Seminar Presentation HandoutDocument1 page"Look Back in Anger" - Seminar Presentation HandoutMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- "Look Back in Anger" - Seminar Presentation HandoutDocument1 page"Look Back in Anger" - Seminar Presentation HandoutMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- "The Waste Land", "Heart of Darkness", "Ulysses", "Waiting For Godot", "Look Back in Anger", "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" - Reading NotesDocument7 pages"The Waste Land", "Heart of Darkness", "Ulysses", "Waiting For Godot", "Look Back in Anger", "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" - Reading NotesMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Beşliu Maria, Presentation HandoutDocument1 pageBeşliu Maria, Presentation HandoutMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The Most Crucial Event in The History of Mankind: Excellent 10Document4 pagesThe Most Crucial Event in The History of Mankind: Excellent 10Maria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Proiect de Lectie Besliu MariaDocument9 pagesProiect de Lectie Besliu MariaMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- "The Waste Land", "Heart of Darkness", "Ulysses", "Waiting For Godot", "Look Back in Anger", "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" - Reading NotesDocument7 pages"The Waste Land", "Heart of Darkness", "Ulysses", "Waiting For Godot", "Look Back in Anger", "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" - Reading NotesMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The Dickensian Hero'S Quest For IdentityDocument4 pagesThe Dickensian Hero'S Quest For IdentityMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Beşliu Maria, Critical Essay - Ideology in John Osborne's Look Back in AngerDocument8 pagesBeşliu Maria, Critical Essay - Ideology in John Osborne's Look Back in AngerMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The American Dream and Slavery - EssayDocument5 pagesThe American Dream and Slavery - EssayMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Mechanicals' Play in A Midsummer Night's DreamDocument2 pagesMechanicals' Play in A Midsummer Night's DreamMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The Most Crucial Event in The History of Mankind: Excellent 10Document4 pagesThe Most Crucial Event in The History of Mankind: Excellent 10Maria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Hopkins' "Pied BeautyDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Hopkins' "Pied BeautyMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Hamlet's Mission of Revenge in Shakespeare's Complex TragedyDocument3 pagesHamlet's Mission of Revenge in Shakespeare's Complex TragedyMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Jane Eyre's Spiritual JourneyDocument4 pagesJane Eyre's Spiritual JourneyMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Bilingual TranslationDocument252 pagesBilingual TranslationBianca Maria100% (2)

- The Relations Between Men and Women in "A Midsummer Night's Dream" - EssayDocument4 pagesThe Relations Between Men and Women in "A Midsummer Night's Dream" - EssayMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Writing Test 2Document2 pagesWriting Test 2Maria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Witches in Macbeth - EssayDocument2 pagesThe Role of The Witches in Macbeth - EssayMaria Mureșan100% (2)

- Jackson Andy Jackson Audrey Elementary Grammar Worksheets PDFDocument98 pagesJackson Andy Jackson Audrey Elementary Grammar Worksheets PDFEvexgNo ratings yet

- Tenses 9hDocument13 pagesTenses 9hMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- Present Simple and Continuous ExercisesDocument1 pagePresent Simple and Continuous ExercisesMaria MureșanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Proverbs CommentaryDocument162 pagesProverbs CommentaryVikram JangaNo ratings yet

- SGS NT TRAINING MATERIAL - 1st EditionDocument48 pagesSGS NT TRAINING MATERIAL - 1st EditionChigozie-umeh OgechukwuNo ratings yet

- Adam Miller Reviewed PDFDocument5 pagesAdam Miller Reviewed PDFRobert F. Smith100% (1)

- Yale University Press Religion 2011-12 CatalogDocument24 pagesYale University Press Religion 2011-12 CatalogYale University PressNo ratings yet

- Why Is Mary Crying - CathoolicDocument13 pagesWhy Is Mary Crying - CathoolicJorge Arturo Cantú TorresNo ratings yet

- Giving It All Away... and Getting It All Back Again SampleDocument27 pagesGiving It All Away... and Getting It All Back Again SampleZondervan67% (3)

- The NET Bible TranslationDocument1,053 pagesThe NET Bible TranslationDieter Thom91% (11)

- How The Catholic Church Preserve Its Compiled Book Called "Bible" - The Splendor of The ChurchDocument11 pagesHow The Catholic Church Preserve Its Compiled Book Called "Bible" - The Splendor of The Churchjoseph arao-araoNo ratings yet

- Nida, E. & Tauber: The Theory and Practice of TranslationDocument226 pagesNida, E. & Tauber: The Theory and Practice of Translationmalicus100% (1)

- CE1 - Translation of The BibleDocument21 pagesCE1 - Translation of The BibleFrannie Alyssa MataNo ratings yet

- 2 Regi 2 NTLR KJV NKJV - Înălţarea Lui Ilie La Cer - Când A - Bible GatewayDocument1 page2 Regi 2 NTLR KJV NKJV - Înălţarea Lui Ilie La Cer - Când A - Bible GatewayAndreiLazarNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Disproving Christianity and Other Secular Writings by David McAfeeDocument79 pagesBook Review of Disproving Christianity and Other Secular Writings by David McAfeeTyler Vela100% (1)

- The Holy Bible, New King James Version PDFDocument1,160 pagesThe Holy Bible, New King James Version PDFCidyNechi Dulce Melodia86% (43)

- Ancient-Modern Bible SamplerDocument102 pagesAncient-Modern Bible SamplerBible Gateway100% (4)

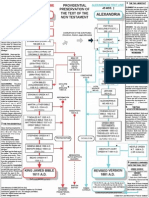

- KJV Bible History ChartDocument1 pageKJV Bible History Chartalbertorivera600100% (1)

- The King James BibleDocument14 pagesThe King James BibleKirsten Florida PfauNo ratings yet

- KJV Greek Interlinear New TestamentDocument541 pagesKJV Greek Interlinear New TestamentJesus Lives100% (1)

- Khongso Chin of MyanmarDocument6 pagesKhongso Chin of MyanmarKhongso ChinNo ratings yet

- Porn Free - Course GuideDocument33 pagesPorn Free - Course GuideCyrell S. SaligNo ratings yet

- Psalm 23 KJV - The LORD Is My Shepherd I Shall NDocument1 pagePsalm 23 KJV - The LORD Is My Shepherd I Shall NakitigreatNo ratings yet

- Epilogue: Finding Favor With God and ManDocument4 pagesEpilogue: Finding Favor With God and ManTNo ratings yet

- Seven Pillars of Wisdom PDFDocument141 pagesSeven Pillars of Wisdom PDFUrusi TeklaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The New Testament Fr. RowelDocument15 pagesIntroduction To The New Testament Fr. RowelJulia Aure MoralesNo ratings yet

- The Orthodox New TestamentDocument672 pagesThe Orthodox New TestamentElida Stupariu100% (1)

- 1 Samuel - Looking On The Heart (Dale Ralph Davis)Document369 pages1 Samuel - Looking On The Heart (Dale Ralph Davis)Rev. Johana VangchhiaNo ratings yet

- KJV Is The Preserved Word of GodDocument33 pagesKJV Is The Preserved Word of GodJesus LivesNo ratings yet

- Turpie - Old - Testament.in - The.new Scribd 2Document309 pagesTurpie - Old - Testament.in - The.new Scribd 2Peggy Bracken StagnoNo ratings yet

- The Shadow of A Great Rock Harold Bloom PDFDocument28 pagesThe Shadow of A Great Rock Harold Bloom PDFmuirNo ratings yet

- 31king James Bibles Beware of Altered KJVDocument10 pages31king James Bibles Beware of Altered KJVjannakarlNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Quote - FINNEGAN, Ruth.Document350 pagesWhy Do We Quote - FINNEGAN, Ruth.Bruno GaudêncioNo ratings yet