Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thisbetheverse

Thisbetheverse

Uploaded by

api-510312262Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thisbetheverse

Thisbetheverse

Uploaded by

api-510312262Copyright:

Available Formats

Jordan Lett

This Be The Verse

Dad never said much about his dad. I knew Grandpa Johnny as the old man that smoked

Marlboros and fit perfectly in the Johnny-shaped hole of the leather couch. He never had much

to say, often because the lung cancer we didn’t know he had made it painful for him to speak. I

had always felt sorry for him. Every Christmas, he would sit idle in front of the TV, a crocheted

blanket resting on his lap, tuning out everyone’s conversations. His wife, my grandma Judy, has

been on oxygen for the past five years, but she still waddled from room to room and cooked

dinner for everyone.

It wasn’t until the last few months of his life that I started to think about how much my

dad looked like him. They shared the same long nose, puffy chin, sunken grey eyes, and the

same frown lines. He watched the same five episodes of How I Met Your Mother every time I

visited, and he was a true Duke fan. Before then, that’s all I knew about Johnny. The day that he

died, no one in the family shed a tear except my father.

“Old Johnny,” my Aunt Maggie said to me late one night as she lit a cigarette outside

Grandma Judy’s house. “He had a lot of problems. He never took it out on us kids. Always on

Mamma. She’s been through a lot.” It was then that Maggie blew smoke past my face and

laughed. “He’d beat the shit out of that old woman.”

But I hardly believed it, as Judy has always been so gentle, and Johnny had always been

so sedentary. “There was no love in that house. No validation.” Apparently Dad woke up every

morning to Johnny’s voice booming over the trucks that would pass by, and he stayed awake at

night listening to the TV at full volume until midnight.

“Why?” I asked Maggie.

Jordan Lett

She shrugged. “Ain’t nothing ever been good enough for him. James used to act out. You know

how much he loves his Mamma. Johnny just turned his hand to James and told him to man up.”

Dad burned down that house on the south side of Statesville after pouring gasoline into a

burning wood stove. Home sick one night, he was tasked with keeping the stove warm. He never

told me why he thought to use gasoline. Maybe he thought it was a shortcut, or maybe they were

out of wood. Sometimes I think about Dad sitting in front of the wood stove, watching the flames

die out, hearing the living room clock tick away the remaining afternoon hours before Johnny

would return.

***

My dad is a Duke fan just like his old man. Sometimes I joke about how I’d love to meet

my dad one day, even though he’s been present in my life for 21 years. In almost every way, we

could not be more different, although he’s tried to make me align with his interests several times.

I served a few aces during my time as a child athlete, but they were all underhand. I was

never quite ready for the ball to return to our side of the net. I jerked my body into action just a

little too late and I had heavy feet as I stomped across the court. All of these things pissed Dad

off. Throughout every game, each time the ball touched the ground on our side, I would look

over to see the progress of Dad’s bald head getting redder and redder. Sometimes he would begin

to sweat, and sometimes he would walk out of the gym. If we’d win the game, he wouldn’t

smile. His frown would sink deeper into the frown lines of his face, and he would dab sweat off

of the crown of his head with a tissue, and he would nod and say, “If you overhanded your last

serve, you wouldn’t have gone into overtime.”

Jordan Lett

I don’t play sports anymore. Dad had attempted to teach me several tricks to his favorite

sports, and how to play it the “manly” way. He would demonstrate how to hold a golf club and

plant his feet while he twisted his body back, as he had done for over half of his life, before

nailing the golf ball. His ball would soar across the field, landing so far away that we couldn’t

see it in the grass. Mine wouldn’t even get off the ground before he stopped me.

Not playing sports was the first affront to his authority. It began to drive him insane to

see me curled up in the round living room chair with a book in my lap. The nights he didn’t

spend outside, fervently cleaning his golf clubs or pushing his lawn mower across already-cut

grass, he would spend pacing in the dining room and ranting.

“If you’re not gonna get off of your lazy ass and do something,” he’d say, “then why do I

feed you? Get up and clean house or something. If you’re not gonna go outside and play, then

you should clean house-- God knows your mother doesn’t do jack shit.”

We’d fight until our arms and lungs gave out, and at the end of the day we’d let ourselves

be swept away. As I grew older, more tired, I spent my time behind a closed door. Headphones

shielded my ears. One time, the floor trembled, and I thought, “I wonder how Grandma Judy is

doing all alone in her house.”

Life has its refrains.

Still, I don’t speak to him despite the fact that I see him every week when I visit my

mom. I don’t invite him to poetry readings. I don’t look at him very often because I’ll begin to

think about how much I look like him. We share the same long nose, puffy chin, sunken grey

eyes, and the same frown lines.

You might also like

- Outofthe AbyssDocument63 pagesOutofthe AbyssCarlosHenrique90% (21)

- Llibre de Cuina de Guy FletcherDocument43 pagesLlibre de Cuina de Guy FletcherJordi FontNo ratings yet

- Dallas O'Neil and the Baker Street Sports Club Series CollectionFrom EverandDallas O'Neil and the Baker Street Sports Club Series CollectionNo ratings yet

- Alantek Coaxial CatalogDocument24 pagesAlantek Coaxial CatalogThuận Trần ChuNo ratings yet

- Progress Test 10Document2 pagesProgress Test 10Ada ZelinschiNo ratings yet

- The SquirrelDocument4 pagesThe SquirrelSana100% (1)

- The Dreadful Revenge of Ernest GallenFrom EverandThe Dreadful Revenge of Ernest GallenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- All You Need Is Love: An emotional, uplifting story of love and friendship from Jessica RedlandFrom EverandAll You Need Is Love: An emotional, uplifting story of love and friendship from Jessica RedlandRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- A Family Reunion: A Different Kind of Ghost StoryFrom EverandA Family Reunion: A Different Kind of Ghost StoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- My Best Friend and the Honeymoon Game: Trouble in Love Series, #2From EverandMy Best Friend and the Honeymoon Game: Trouble in Love Series, #2No ratings yet

- Guys Read: A Fistful of Feathers: A Short Story from Guys Read: Funny BusinessFrom EverandGuys Read: A Fistful of Feathers: A Short Story from Guys Read: Funny BusinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Joey-Short StoryDocument14 pagesJoey-Short StoryRin ExequielNo ratings yet

- No One Wants To Be Joey NoodlesDocument4 pagesNo One Wants To Be Joey NoodlesAnthony CrisafulliNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Revised No FootnotesDocument7 pagesEssay 2 Revised No Footnotesapi-661301019No ratings yet

- 212 My Oedipus Complex TextDocument11 pages212 My Oedipus Complex Textkm ershadNo ratings yet

- Dad and I: Written By: Brad JonesDocument4 pagesDad and I: Written By: Brad JonesBrad JonesNo ratings yet

- SampleDocument4 pagesSampleapi-301660874No ratings yet

- Untold Stories: Intro Writing Assignment-PromptDocument11 pagesUntold Stories: Intro Writing Assignment-Promptapi-311823660No ratings yet

- Minolta Price List 1964Document16 pagesMinolta Price List 1964azamamaNo ratings yet

- POS Printer SRP-350plusIII BixolonDocument2 pagesPOS Printer SRP-350plusIII BixolonBixolonGlobalNo ratings yet

- SManual CL001943 CLP675Document173 pagesSManual CL001943 CLP675Pierre JAUMIERNo ratings yet

- Past Simple 11678Document1 pagePast Simple 11678Oskarle Alvarez ChacoaNo ratings yet

- Analysing Components of Invitation-BadrilDocument3 pagesAnalysing Components of Invitation-Badrilalifbata tsajimhaNo ratings yet

- Ir2530 2525 2520 SM PDFDocument402 pagesIr2530 2525 2520 SM PDFFlorin BargaoanuNo ratings yet

- Aeris XR1 NX Dive Computer ManualDocument72 pagesAeris XR1 NX Dive Computer ManualENo ratings yet

- Merchant of VeniceDocument5 pagesMerchant of VeniceArun RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Q1-Lesson 1.2 - Define and Understand MarketingDocument20 pagesQ1-Lesson 1.2 - Define and Understand MarketingJERRALYN ALVANo ratings yet

- Cleaning The EOS 5D MKII ViewfinderDocument21 pagesCleaning The EOS 5D MKII Viewfinderdeep42No ratings yet

- Lion KingDocument2 pagesLion KingTenneth BacalsoNo ratings yet

- Toshiba 26HF84Document9 pagesToshiba 26HF84ik001No ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument2 pages1 PDFANDRES SIGIFREDO GOMEZ FIGUEREDONo ratings yet

- Digital Dice With Numeric DisplayDocument2 pagesDigital Dice With Numeric DisplaychakralabsNo ratings yet

- 2015 04 16 Hifi Jean Maurer Son Et Image enDocument5 pages2015 04 16 Hifi Jean Maurer Son Et Image enParker FlyNo ratings yet

- Nokia c7-00 Rm-675 Service Schematics v2Document12 pagesNokia c7-00 Rm-675 Service Schematics v2Jairo Fabian Campos DuqueNo ratings yet

- FI SD IntegrationDocument2 pagesFI SD IntegrationPraveen KumarNo ratings yet

- 7 Rocking Around The Christmas Tree - Andy BeckDocument3 pages7 Rocking Around The Christmas Tree - Andy BeckSmp YpkransikiNo ratings yet

- Existential Thought in American Psycho and Fight Club PDFDocument120 pagesExistential Thought in American Psycho and Fight Club PDFKashsmeraa Santhanam100% (1)

- Laser Show System Model CVLC-LT223Document5 pagesLaser Show System Model CVLC-LT223Owais AkhlaqNo ratings yet

- SSSG INGLESE Present PerfectDocument3 pagesSSSG INGLESE Present PerfectGraceNo ratings yet

- Sage's Will Locations and Guide - The Legend of ZDocument3 pagesSage's Will Locations and Guide - The Legend of ZcaterinaNo ratings yet

- 2014 SRA Signings TerminationsDocument45 pages2014 SRA Signings TerminationsDarren Adam Heitner0% (1)

- Pikachu Rattle PatternDocument3 pagesPikachu Rattle PatternElla TannNo ratings yet

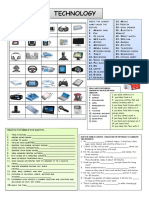

- Technology: What About Household Appliances Match THE With Their USEDocument2 pagesTechnology: What About Household Appliances Match THE With Their USEJuan Olivares50% (2)