Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dunsmore Welcoming Their Worlds La PDF

Uploaded by

Deisy GomezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dunsmore Welcoming Their Worlds La PDF

Uploaded by

Deisy GomezCopyright:

Available Formats

KaiLonnie Dunsmore, Rosario Ordoñez-Jasis, and George Herrera

page

327

Welcoming Their Worlds:

Rethinking Literacy Instruction

through Community Mapping

E

ric rarely did his homework. He is a bright a large metropolitan area in the western United

sixth-grade student who is more focused States, became very excited about how this sin-

on having fun and making his fellow class- gle effort to integrate the literacies of home and

mates smile or watch in awe at his bravery than on school transformed student learning. Before that

following the classroom norms and engaging with moment, conscious of the economic poverty of

the curriculum. His teacher, George Herrera, says, many of his students, he had rarely asked them to

“He is one that we call ‘travieso’ [Spanish for mis- connect school work to conversations, practices, or

chievous or naughty]. Not a bad student but not resources at home. A number of his students were

one very engaged.” Yet, today, he came into class technically homeless, living in converted garages

clearly excited about his homework in the poetry or small sheds behind other homes (George, inter-

unit and, for the first time, fully engaged. George view, 11/2011). George believed that by not asking

describes the situation this way: students to bring things from home, he had been

Eric’s face and slouching body could easily be inter- “doing them a favor,” and “making the playing field

preted as saying, “Is this lesson over yet?” However, more even.” Over time, however, as he engaged in

this time there was something significantly different a form of community mapping (Tindle, Leconte,

and profound about the change in his demeanor and Buchanan, & Taymans, 2005), he began to develop

engagement. As it turned out, when his mother was ex-

an increasing awareness of the literacies already

pecting him, she had written an acrostic poem about

him coming into her life. She had never shared that present in students’ home lives, as well as the lack

poem with him. As a result of this assignment, she took of time and space in his classroom for the kinds of

out the poem and read it to him for the first time. He talk and texts that came from home.

was so thrilled that this poem existed about him, and he George Herrera’s community mapping work

was eager to share it with his classmates. emerged from his participation in a Family Literacy

In response to this particular unit, 31 of 32 students Community of Practice or CoP (Wenger, 1999), a

brought poems in from home. During the in-class group formed around a collectively owned inquiry

writing activity around their poems, Eric was ener- about the literacies in students’ family and commu-

getic and proud to share his poem. And he was not nity life and how those might support school-based

alone. George was taken aback at his students’ literacy learning. As part of this work, George was

“eagerness to get on task,” noting: using the analytic and conceptual tools of an eth-

This moment was somewhat surreal for me. . . . I kept nographer to map the literacies in the surrounding

wondering what happened. Up until they brought their community. This process was changing how he

poems from home, it had been me expending the great- thought about the role and value of out-of-school

est energy and making the utmost effort to keep stu- literacy practices and how they could support school

dents engaged. Now, the engagement was organic, and

learning. Along with the other teachers in the CoP,

the energy was being produced by them.” (written re-

flection, 12/2011) George had begun to redefine his understanding of

school-based literacy to recognize the multiple and

George Herrera, an elementary teacher in a mid-

complex literacies available to students—literacies

size urban K–12 school district located outside of

he had typically ignored. So, while he cast it as a

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

Copyright © 2013 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.

May2013_LA.indd 327 KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

328

“spur of the moment” decision to ask students to engagement, performance, and meaning making

bring a poem from home, George Herrera’s instruc- were mediated by the creation of a learning con-

tional practice had begun to reflect new insights text that valued and connected student words and

based upon his CoP inquiry, “How might home- worlds (Freire & Macedo, 1987).

centered literacies service the school curriculum

even more?” Theory

In this article, we focus on George Herrera as Community mapping is an inquiry-based method

both teacher and learner to examine the ways in in which “mappers” discover, gather, and analyze

which he developed insights about home and com- a rich array of resources from a specific geographic

munity literacy practices, and then intentionally area to develop new understanding of the cultural

drew upon these insights to facilitate school-based and linguistic practices that make up its commu-

literacy learning for his students. We describe his nity life (Ordoñez-Jasis & Jasis, 2011). In special-

change in practice in the context of the learning and ized fields such as sociology, urban planning, and

mapping activities of all members of the community environmental science, community mapping is used

of practice of which he was a member. Through this to build knowledge and awareness of community

lens, we look closely at learning and the ways that

S T R AT E GIE S T H AT P ROMOT E S T U D ENT EN GAGEM ENT

Mr. Herrera used many strategies to engage the students in his classroom. These resources from ReadWriteThink.org

can highlight a few of those strategies:

Rummaging for Fiction: Using Found Photographs and Notes to Spark Story Ideas

In this lesson, students use found notes and found photographs as inspiration to help them identify subjects, settings,

characters, and conflicts for pieces of creative writing.

http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/rummaging-fiction-using-found-1108.html

Utilizing Visual Images for Creating and Conveying Setting in Written Text

This lesson supports students in grades three through six as they communicate story setting to their readers through

the use of visual image prompts. Activities include individual work and cooperative learning group work, as well as

whole-class discussion.

http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/utilizing-visual-images-creating-30506.html

A Trip to the Museum: From Picture to Story

Visit a museum or art gallery (either online or in person) with children and teens, helping them find inspiration for a

story based on a piece of art that they particularly enjoy or relate to.

http://www.readwritethink.org/parent-afterschool-resources/activities-projects/trip-museum-from-picture-

30302.html

Looking at Landmarks: Using a Picturebook to Guide Research

This lesson uses Ben’s Dream by Chris Van Allsburg to highlight ten major landmarks of the world. Students research

the landmarks and present their findings to the class.

http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/looking-landmarks-using-picture-841.html

—Lisa Fink

www.readwritethink.org

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 328 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

329

assets, needs, and historical/demographic trends and to co-construct meanings that they committed

(Tindle, Leconte, Buchanan, & Taymans, 2005). to immediately apply to actions as educators.

Tredway (2003) describes community mapping as

an inquiry-based method that has the potential to Methods/Context

change the perspective of the teacher from one of This study was constructed as a teacher action

an outsider to that of an insider. research project where schools and communities are

Luis Moll’s work (see Moll & Gonzalez, 2004) viewed as sites for both learning and inquiry (Lytle &

on funds of knowledge has helped to frame teacher Cochran-Smith, 1992). Teacher research is a means

action research—including teachers’ observations to construct new knowledge and improve practice;

and documentation of how students and community its power and potential are enhanced when teach-

members attach meaning to language and literacy ers have the opportunity to collaborate and critically

practices—as a central approach to developing reflect with others to expand the number of shared

effective curricula in which out-of-school knowl- perspectives (Hobson,

edge practices support school-based knowledge 2001). As such, this study Teacher research is a means to

practices. New understandings gained from sys- is centered on George

tematically locating language and literacy resources construct new knowledge and

Herrera, an experienced

through inquiry-based investigative work such as elementary school teacher improve practice; its power and

community mapping may also broaden teachers’ of 17 years, as a member

understanding of literacy instruction so they may potential are enhanced when

of a teacher-led CoP that

approach reading, writing, speaking, listening, focused on family literacy. teachers have the opportunity to

and viewing as permeated by social and emotional Using his students’ com-

issues (Gee, 1989; Taylor, 2010). In other words, collaborate and critically reflect

munities as settings for

by mapping the literacies in students’ cultural lives study and critical analy- with others.

in the home and the surrounding community and sis, George carried out a

intentionally working to situate those authentically teacher inquiry project that required him to map the

in the core of school-based practices (Auerbach, cultural, linguistic, and literacy “geographies” (Moll,

2001), teachers allow the emotional and intellec- 2010, p. 454) surrounding his school site.

tual dimensions of literacy—which make prac- George and the other CoP members visited

tices authentic and purposeful—to guide student local religious, cultural, civic, and commercial sites

learning. to identify the literacy practices that were typical

George’s attempts to tap the funds of knowl- and the ways families and communities engaged

edge of his students and families involved appropri- with them; they met with parents in focus groups

ating the ethnographic tools of community mapping and interviews to discuss literacy routines and prac-

and applying them to his students’ local communi- tices; they created physical and conceptual maps

ties. These data-gathering methods include collect- delineating the values and knowledge in the com-

ing and interpreting surveys, interviews, artifacts, munity that could be an effective resource to sup-

and recorded/documented observations of com- port school-based literacy learning. Unlike the fam-

munity events. Community mapping also involved ily literacy activities in their school, which focused

a process of deep reflection and conversation on getting parents to attend evening academic events

between George and other members of the commu- or utilize particular strategies or resources at home,

nity of practice to understand the patterns, themes, these teachers actively worked to instantiate in their

and relationships between the worlds of students classroom practices their growing belief in the inter-

in and out of school. CoP meetings provided an connected nature of in- and out-of-school literacies.

opportunity for George and his colleagues to share During mapping activities, George took field

what they had learned from the activities they had notes and maintained a journal to record new find-

selected to “map” in the weeks between meetings, ings or discoveries that caused him to question

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 329 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

330

his previous understandings about families and/or curriculum was a central theme of students’ experi-

the community. Through this ongoing process of ence as learners in this work and of George’s insight

critically reexamining and reinterpreting his own as a teacher. As a result, all names in this article are

knowledge and experiences, we believe George was real. We believed it important that participants own

able to enter the community with a fresh perspec- their own stories.

tive and a new disposition, allowing him to gain a

more comprehensive understanding of the commu- What Is a CoP and Who Are the

nity and the reciprocity that could be developed in Members of the Family Literacy CoP

literacy practice as students engaged in composing in This Study?

and comprehension activities that were authentic There were 10 members of the Family Literacy CoP,

across contexts. one of whom was a parent invited to join the group

mid-year as the group became more conscious of

Who We Are? their need to bring the voices of parents into the

As the three authors of this study, we work in design of the inquiry and analysis of data. This dis-

diverse organizations (foundation, university, pub- trict has nearly 16,000 students in 23 schools, 58%

lic school) but share a commitment to collaborative of whom are eligible for free and reduced lunch,

inquiry that improves student literacy achievement, and 34% of whom are English Language Learners.

especially for those students whose linguistic and Ethnically, the district is approximately 60% Latino

socio-historical experiences often marginalize and and 30% Asian, with very small numbers of Euro-

disenfranchise them in classrooms. In one sense, pean American, African American, and other eth-

George Herrera was, along with other CoP mem- nic/racial groups.

bers, originally a research “subject”; Dunsmore and The district itself has undergone rapid demo-

Ordoñez-Jasis were given access to his reflective graphic change over the past 20 years, moving from

journals, action research field notes, as well as per- an agrarian community with European American

mission to attend and take field notes on CoP meet- dominance to sprawling urban and suburban neigh-

ings, conduct semi-structured interviews, video/ borhoods with either Asian American or Latino

audio record CoP meet- communities that are predominantly immigrant or

Naming oneself and locating ings and calls, and log first generation. There is a constant theme in dis-

one’s identity in the academic emails for later analysis. trict conversations about the need to build “recipro-

In the process of analyz- cal relationships” with families; this goal, in fact, is

curriculum was a central ing data for this article codified in the 2008 strategic plan (Rowland Uni-

theme of students’ experience and engaging in “mem- fied School District, 2008).

ber checking” (Creswell, The majority of George’s CoP members self-

as learners in this work and of 2009), however, Her- identified as Latino; half had a personal connection

George’s insight as a teacher. rera became more “co- to one of the school communities (e.g., attended the

researcher” as he actively district as children or currently lived in the district).

and skillfully moved back and forth between his The CoP members represented different schools/

roles as research subject and researcher, wherein grades in the district and self-selected into this

he contributed to analyses of the student work, vid- group, which was supported by the district as part

eotaped instruction, and student interviews that all of a systematic effort to create voluntary, teacher-

parents and students in the classroom had consented led learning communities on topics identified by

to share. In addition, during follow-up interviews teachers themselves.

with the focal students in this article, they requested The explicit rationale for communities of prac-

(and parents consented) for their real names to be tice in this district was built on a theory of action in

used (we chose to use first names only). Naming which sustained change in literacy achievement for

oneself and locating one’s identity in the academic all students was premised on creating a professional

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 330 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

331

culture in which collaboration, inquiry, and shared mapping trips to enter a building with “Welcome.

agreements about practice characterized the daily Come In” written in Spanish on the front (George,

work of teachers. Based upon the research and the- personal communication, 7/2011). With no signs

oretical grounding of Etienne Wenger (1999), com- indicating its purpose, he imagined multiple scenar-

munities of practice reflected ways people learned ios (including a drug rehabilitation center); it turned

together (around areas of common interest; through out to be a vitamin store. Over time, George gained

self-directed and shared inquiry, with a focus on more comfort and skill with the tools of recogniz-

developing individual and collective expertise). ing, observing, and recording the literacy practices

The community of practice model employed and resources of families and communities.

as part of this work was integral to the commu- Although George had worked in the district for

nity mapping process, since meaning making and many years and shared similar cultural and linguis-

action for both the group and the individual were tic backgrounds with many members of his school

tied to the conversational tools and protocols teach- community (which was predominantly Latino),

ers used. The question “What are we learning?” he was unsure how to use what he was learning

in the community mapping process was always about students and community literacies as a way

followed by “And now what will we do?” Specifi- to organize curriculum. In a second round of com-

cally, the collaboration allowed George to learn munity mapping, George and two members of the

about the community and its literacies from other CoP decided to conduct parent interviews and home

participants. He often found the mapping activities visits in order to develop a better understanding of

of other CoP members equally important for his families’ language and literacy-related beliefs and

own learning. George explained that, “It’s that col- practices.

lective piece that was most powerful. . . . we bring While interacting with parents and their chil-

it all together and we all connect and we find the dren, George observed several examples of story-

themes” (George, interview, 5/2011). telling, particularly those stories or consejos (fam-

ily or generational, morally oriented teachings) that

Data & Interpretations held cultural and religious value for the families.

He also discovered ways in which parents engaged

Making the Unfamiliar Known their children in culturally relevant literacy-based

Although extremely outgoing, comfortable with activities. These included creating and designing

talking to parents and inviting them into his class- calaveras (sugar skulls)

room, fluent in Spanish, and conversant in the cul- for Day of the Dead and While interacting with parents

tural mores of the Latino community, when George teaching games such as

and their children, George

ventured out to observe, interview, and capture Loteria (Mexican game

practices, he was surprised at how nervous and similar to bingo) and La observed several examples of

uncomfortable he was outside of his classroom. Pirinola (traditional Mex-

storytelling, particularly those

When visiting the public library just blocks from ican game). At the follow-

his school, he entered with a clipboard, walked ing CoP meeting, George stories or consejos . . . that held

around the library, and stood back observing a folk excitedly reported back to

cultural and religious value for

music performance. Taken for an “inspector,” he the group about the many

realized that he was using his clipboard to distance rich practices he was able the families.

himself by creating a safer space as a visible out- to identify. These candid

sider. Surprised by his discomfort, he realized that conversations with families in their homes also con-

he needed to develop skills and strategies to explore tributed to a significant shift in George’s perspec-

places and spaces that were unfamiliar. Because of tive; he moved from viewing schools as the center

his “fear of the unknown,” it took him three separate of the community toward a renewed appreciation

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 331 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

332

that schools and households actually inhabit the George explained that “the most important

community equally. thing that I have seen is that by going out into the

It’s so different when you walk inside of a house, when community and talking to parents, I learn more

you’re sitting there with a family. It changes your per- about students. If I learn more about my students,

spective. . . . I always saw the school as a center of the I can connect better with them” (George, interview,

community and they come to us. . . . We see ourselves 5/2011). The next step was to figure out how to

as the center of the community but to them, [school is]

build curriculum that reflected that connection.

just one aspect [of their world].

After conducting the home visits and parent Connecting to the Classroom

interviews, the CoP reflected upon the process of As the school year was quickly coming to an end,

community mapping and their collective insights, George was still struggling to identify ways in

which they called their “aha” moments. Table 1 syn- which his growing knowledge about his students’

thesizes the CoP’s summarizing and sense making as family and community literacies could inform his

the group members moved to more actively explore instructional practice. In CoP discussions and indi-

implications for their pedagogy and practice. vidual reflections and interviews, George voiced the

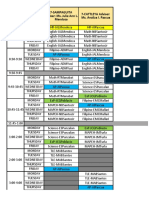

Table 1. A synthesis of the CoP’s mapping steps and subsequent insights

Community Mapping Activities Significant “Aha” Moments for CoP Members

Scout the geographical location to identify possible Recognized stereotypes of community and redefined

community resources. CoP members drove, walked, and function and meaning of spaces, events, organizations (e.g.,

used public transportation to learn about the community’s local park that was deemed “unsafe” by teachers and staff

libraries, parks, churches, small family-owned businesses, was actually a vibrant community center with art and dance

and nonprofit agencies. classes, organized sports, cultural events, and activities).

Photograph and/or videotape the various places of interest. Saw incredible diversity of resources, organizations,

CoP members photographed interesting cultural and and culturally significant spaces with which they were

linguistic symbols found throughout the community. previously unfamiliar; when images were publicly shared,

they discovered surprising relationships (e.g., a teacher in

Dunsmore’s school was a local library president; others

were local church members) that had been hidden in the

professional life of school teaching.

Collect artifacts. CoP members collected documents such Learned that many parents were not aware of the

as brochures, maps, and pamphlets from the various sites community resources available to them. Members

to share with the other members. brainstormed ways to share this information with families

districtwide. Few teachers were aware of these resources

or that the resources could support their work (e.g., public

library close to school, which none had ever visited).

Survey or interview parents/primary caregivers. CoP Reframed traditional notions of literacy to include culturally

members developed survey and interview protocols aimed and linguistically relevant literacy practices (poems, songs,

toward developing a better understanding of how parents games, storytelling). Recognized a need to create critical

construct literacy experiences for children. spaces for student voice and student interest in pedagogy

and practice.

Conduct home visits. CoP members visited the homes of Moved from viewing schools as the center of the

several families with the goal of learning about families community and the locus of educational power and control

and developing positive, reciprocal relationships with toward an understanding that schools and households are

parents. critical components of the same community.

Meet and interview community informants. Teachers Developed insight into how multiple and situated

and parents spoke with community members (residents, community literacies support, rather than contradict,

librarians, bus drivers, pastors, small business owners) to literacy learning within the classroom (e.g., members

obtain various perspectives on literacy-based resources learned about the efforts of local churches to promote

and community assets. literacy in children’s primary language—such as Spanish,

Korean, Chinese—in afterschool and weekend programs).

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 332 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

333

need for a significant “shift in paradigm” in order to

practice a pedagogy of inclusion that was more rep-

resentative of multiple and situated literacies (field

notes, 3/2011). This reflected a new understanding,

grounded in data, about how community literacies

support, rather than contradict, literacy learning

within the classroom. It also led him to think about

the purpose of the classroom routines: “I’m begin-

ning to make a distinction between reading and writ-

ing and literacy,” George explained in a CoP meet-

ing. “Literacy means that you are reading things that

are important to you, that matter to you, that some-

how change your way of thinking or drive you into

making a change for something, and that’s where

I’ve seen students become more passionate” (field

notes, 3/2011). In his classroom, he began to try out

half-formed ideas about what instructional practices

that connected students worlds’ might look like.

In the context of teaching his sixth-grade stu-

dents a six-week standards-based poetry unit,

George decided that for the next CoP meeting, he

would have some specific actions he could share Figure 1. Samantha recognized George’s local photo as the

about how he had connected the community to his front of her home.

classroom instruction. George explained his process:

One afternoon, I had a few minutes to spare, so I got father had purchased it and built the glass enclosure

in my car and started driving around the community. when her aunt was very sick; it also commemorated

I was on a quest to photograph anything that might be a Samantha’s middle name (Guadalupe).The aunt

cultural or linguistic symbol. . . . After a few moments

got well and the statue remained as a testimony to

of enjoying my pictures . . . [I] realized that the pictures

in and of themselves, colorful as they were, had mini-

their faith in the Virgin. The mainly Catholic Latino

mal if any value for me as a teacher. “So what?” The immigrant neighborhood used it as an altar for their

next day at school I was not sure of what to do with the own petitions and memorials. Most of the students

pictures, so I decided to show them to my students to in the classroom were familiar with it. The energy

see what value the pictures might have, if any, for them. and engagement was so “passionate and real” that

. . . As soon as I flashed the first picture on the screen,

George created an extension activity to utilize their

their engagement, disposition, and enthusiasm shifted

into what I refer to as a heightened state. (written reflec-

motivation and interest in support of writing. They

tions 12/2011) were requested to select four photos and write a short

prose poem for each that described their personal

Together, students began making meaningful

connection. Student enthusiasm with the writing task

connections with the images of their worlds. After

was “unparalleled, reflective, and profound” (written

showing a variety of photos, George displayed an

reflections 12/2011). He later noted that:

image of a seven-foot-tall statue of the Virgin Mary,

surrounded by candles and encased in glass. It sat by As a teacher, I find myself at times trying to persuade

students to invest themselves in the writing task. That

the street in front of a house (see Fig. 1). One student,

persuasion was not necessary here. Upon reading their

Samantha, exclaimed with surprise and pride, “That’s writings, the lesson for me was how connected and

my house! That is our statue to Mary.” Samantha interconnected my students were to their community.

explained that this was the Virgin of Guadalupe. Her Samantha’s writing on the Virgin of Guadalupe was

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 333 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

334

especially touching. Though she struggled with the and personal connections students made with the

writing exam a few days later, her thoughts and lan- community images. Inspired by this experience,

guage flowed beautifully.

the group discussed the power and potential of tak-

Samantha, classified as an English Language ing a more student-centered approach by providing

Learner, had struggled with completing the district opportunities for students to actively negotiate and

English Language Development (ELD) benchmark “decode” the multiple literacies within their own

writing exam that George had administered and communities (field notes, 4/2011). Soon thereaf-

scored. Writing, George noted, had been a labor for ter, George made another “spur of the moment”

her all year. In this assignment, writing about an instructional decision. He asked students to bring

aspect of her family life that was deeply meaning- in a poem from home that was significant to them.

ful and of which she was extremely proud, she was According to George, this simple request created

intensely engaged. She was very excited to share a “change in their energy and disposition that was

the writing with her classmates and teacher as well immediate and palpable that caused me to be opti-

(teacher reflection, 5/2011). mistic that at least five or six students might bring

George noted in amazement that the writing poetry artifacts from home” (written reflections,

she produced about this important family icon had 12/2011). However, the following day when he

a significantly higher quality and quantity of words arrived at school:

and provided evidence of a two-point increase in I was surprised to see that many of my students were

her ELD level (as measured by the district rubric); already waiting outside of the classroom door sharing

it was far more advanced than anything she had their poetry with each other. . . . Of the 32 students in

produced throughout the year. In addition, she my classroom, 31 brought back some form of an artifact

with a poem that was meaningful to them. The average

sustained the writing to

Eric described the shift in his complete an organized, for homework return is rarely that high. Swiftly, in order

to focus their energy . . . I asked students to write about

engagement and interest in coherent, engaging piece, the specific poem they brought in, where it was kept in

something that rarely hap- their house, and why it was meaningful to them. Their

learning, writing, and talking pened and not without passion and connection to their writing could be sensed

in their intense concentration and the manner in which

about poetry as directly centered significant support and

their pencils moved across the pages. . . . [This] dictated

prodding by the teacher

on finding a connection to his (email, 12/2011). Saman- that I take a step back and become a facilitator of what

they wanted to do. . . . I learned about their hopes, fears,

mother through poetry. tha admitted putting more and dreams.”

energy into this writing

Especially eye-opening was the engagement of

because “it was what I really feel about real life”

Eric, the aforementioned disengaged and disinter-

(Samantha, interview, 5/2012). For Samantha, the

ested student. Eric was suddenly eager, present, and

ability to talk and write about something with a

articulate in writing when talking about the poem

deep personal and family connection was more than

his mother had written about him. Eric described

an opportunity to utilize her prior knowledge, it was

the shift in his engagement and interest in learn-

an opportunity to connect to and share her feelings,

ing, writing, and talking about poetry as directly

her values, her beliefs through literate practices

centered on finding a connection to his mother

(speaking, writing, interpreting iconography) that

through poetry: “I didn’t feel really energetic about

were “real life.”

them [poems] because I wasn’t a really good poem

Curriculum That Names person myself” (Eric, interview, 5/2012). Then he

Me and My Community was assigned to locate a poem from home. When

he asked his mother for help, she shared poetry that,

Two weeks later at the CoP meeting, George

unbeknownst to him, she had periodically written

recounted this “spontaneous” classroom activity

over the years. “She had poems,” he commented

with the other members. He described the poignant

“and, well, I turned out to like them because they

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 334 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

335

were about me when I was small, and she actually He was now determined to use the three-week

was really creative about the writing.” He talked Memorial Unit (the culmination of the poetry unit

about how reading them made “me feel that I was that connected to social studies goals and bridged

cared for and my mom, all those things my mom the Memorial Day week-

said in the poem were nice and just makes me feel end) to integrate students’ [George was determined] to

like really happy and to know that she took her time worlds into the classroom

integrate students’ worlds into

to write those,” and although he thought he might by building upon what he

be “shy, embarrassed” to share the poem with his had learned—that student the classroom by building

classmates, he wanted to “show my mom that I engagement and increased

upon what he had learned—

like what she does so she can also feel important” achievement in writing

(see Fig. 2). For Eric, his connection to the Lan- result from connecting to that student engagement and

guage Arts Standards came through a conversation experiences with family

increased achievement in

at home, with his mother, and by reading and shar- meaning and value. He

ing with his classmates poetry that had meaning in started by having a dis- writing result from connecting

his family. cussion with his students

to experiences with family

George saw that letting “poetic words of the about the national tradi-

students’ worlds” come in did not take any planning tion behind this holiday. meaning and value.

or time, but it did require a belief in the capacity Much to his dismay, their

of his students to engage at a cultural and spiritual interest was “lukewarm at best.” Then, a few stu-

level with their teacher and their classmates, as well dents recalled that some of the photos he had pre-

as their willingness to share their intimate world viously shared included familiar murals honoring

with the world of the classroom. Thinking back on soldiers in their community, and they requested that

the ease with which he was able to open a space for he display them again.

home literacies, he noted that “there was also a con- Taking on the role of community informants,

nection between sixth-graders searching to claim an the students proceeded to share with the class other

identity and a process that validates who they are memorials in the community. In the past, George

and what matters to them” (George, personal com- would have typically redirected this conversa-

munication, 12/2011). tion back to what students knew about Vietnam or

about memorials honoring Ameri-

can soldiers (George, interview,

6/2011). In fact, he had done so

when teaching this unit to his

previous year’s class. Then, sev-

eral students suggested that the

Vietnam Wall was like a “memo-

rial” that had been erected on the

school property. Repeatedly, he

told students that there was no

memorial at the corner nearest

the school, but the students kept

insisting there was. When George

drove home that evening and

passed that corner, he noticed the

weather-beaten flowers, stuffed

Figure 2. Eric makes a meaningful connection with a poem his mother wrote animals, candles, and wreaths that

while pregnant with him. sat commemorating an accident

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 335 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

336

and the loss of a community member at that loca- the boys even wore ties (field notes, 5/2011). The

tion. Instantly, he realized that he was thinking highlight of the event was Mrs. Elsa, who was per-

about memorials in terms of statues, but students sonally invited by the students as a guest speaker.

were thinking of the act of using space to remember. She spoke about her son and why it was important

Understanding what students were noting, for her to remember him. She shared the things she

he still thought there was a significant difference does to pay tribute to his memory, and she spoke

between these private acts and the learning he about the tree and her feelings toward it. Then a

wanted them to have about the Vietnam War Memo- student asked if there was a poem that reminded

rial. Eventually, however, George came to realize her of her son. She carried one with her but was

that students needed an opportunity to fully con- unable to read it, asking instead if George would

nect their community with classroom concepts. As read it for her. George remembers the intensity of

a result, he decided to build this unit around the that moment, when sixth-grade students on the sec-

“memorializing” practices of students (George, per- ond to last day of school sat quietly, attentive, and

sonal conversation, 6/2011). intensely engaged. Some students cried as they lis-

In the past, George had rejected local customs tened to the poem. After Mrs. Elsa left, the students

and practices as different from the school-sanc- “begged” him for time yet that day to write her a

tioned knowledge; now he sought to see in his stu- follow-up letter (see Fig. 3). He noted:

dents’ experiences the embodiment of concepts that Keeping them on-task was effortless. If anything, the

intersected their worlds. Students listed numerous challenge was bringing the writing segment to a close. As

sites as well as family practices around remember- I was putting the letters together to deliver to Mrs. Elsa, I

ing and honoring those who have passed. He showed was struck by two major things. One was the level of stu-

dent voice, heart, and sincerity. The other was the natural

students a tree planted on the school grounds in

flow of their writing that is frequently lacking in many of

memory of the deceased son of a school secretary, their writing products. For example, one student, Jenni-

Mrs. Elsa, who also lived in the community. Con- fer, struggled all year to include her voice in her writing.

necting the abstract concept of a memorial to sto- In her letter to Mrs. Elsa, she found her voice, and I was

ries and symbols that were tangible, relevant, and especially touched by her prose (see Fig. 3).

meaningful to students heightened their interest. As

a result, students in his class suggested that they cre-

ate their own memorial space in the classroom and

hold a remembering event. George was hesitant at

first, since scheduling constraints meant this would

happen on the second to last day of school.

Parents and community members were quick to offer

their support for this event. Students wrote either let-

ters or poems to soldiers who lost their lives. . . . Some

offered to bring flowers or candles, others photos, pins,

medals, certificates, and other service memorabilia. A

few students asked if they could also place a picture of

a lost loved one at the memorial. My first instinct was

to say “no” because the project was focused on remem-

brance of loved ones who have served in the military.

Fortunately, the little community mapping voice in my

head told me to embrace the students’ suggestions, and

we created a more inclusive Memorial Project. (George,

written reflection, 12/2011)

The day of the unveiling, students decided on

their own that it was a “dress-up event.” Several of Figure 3. Jennifer writes to Mrs. Elsa after hearing her

speak about the loss of her son.

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 336 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

337

Jennifer explained that this writing gave her that intentionally connected the world inside of

“the liberty to express myself,” and it was about school with that outside. “That’s when it [my teach-

something that “I felt really connected to,” and ing] came to life” (George, interview, 12/2011).

“because it had to do with me” it supported “con- Through the monthly CoP discussions, reflec-

necting to the teacher” (George, interview, 5/2012). tions, and analysis of data gathered as part of the

She commented that she had come to see that poetry community mapping project, George began the slow

and facts in books about memorials actually “con- process of reframing traditional notions of literacy

nect to, like, real life and how you live right now.” to include culturally and linguistically relevant lit-

For George, the event invited student, family, eracy practices, such as the ones uncovered during

and community worlds to create a learning space the home visits and par-

in which motivation and engagement were high and ent interviews mentioned George’s learning within the

the literacy practices surrounding the event captured above. George’s learning context of a CoP helped him

students emotionally as well as intellectually. George within the context of a CoP

noticed that the writing in the letters to Mrs. Elsa helped him to integrate to integrate daily classroom

was, for many of the students, a dramatic improve- daily classroom instruc- instruction with vision for

ment over what he typically saw in classroom writ- tion with vision for teach-

ing. The letters featured longer, more complicated ing that was built upon teaching that was built upon

sentences, more detail, and increased length (more collective insights about collective insights about

words!). Evaluated on the district rubric, the writing students’ out-of-school lit-

consistently had higher voice, more sophisticated eracy practices. Through students’ out-of-school

description, and better organization. By creating a conversations with col- literacy practices.

personal connection and an authentic audience and leagues, George began to

purpose, students became engaged, and the facts in redefine and broaden the practices that “counted”

what Jennifer described as “the books” came to be as literacy and develop beliefs about the kinds of

part of their real life, just as real life entered into the curricular experiences that simultaneously tapped

core of classroom conversation. local expertise and knowledge and supported (and

extended and refined) school-based literacy goals.

Discussion George Herrera is considered an excellent

This article examines how a teacher in a CoP with teacher and, by many accounts, holds the back-

a focused inquiry on family literacy utilized ethno- ground, experience, and practices needed to con-

graphic tools and methods to map the community struct classroom pedagogies that are culturally

and family literacies of his students and use that responsive and inclusive. He is viewed by par-

knowledge to build curriculum that connected stu- ents, colleagues, and administrators as a caring

dents’ in- and out-of-school worlds. In the initial and accessible teacher, hard working, and con-

conversations about the goals for family literacy, stantly engaged in professional learning and action

George talked generally about making families wel- research to improve his practice. Yet, George

come in the classroom. Mapping the literacies pres- explains, it was the process of community map-

ent in families and schools moved him to place the ping and the collective meaning making in his CoP

literacies of the home and community at the heart that provided the impetus and conceptual tools he

of instructional design and literacy practice. By the needed to reinvent his teaching in ways that better

end of the year, he was wondering how he might allowed student voices and knowledge to inform

“develop curriculum units with parents” (recorded and guide instruction.

CoP session, 5/2011). For George, the focal case Through this work, George began creating

in this story, the community mapping process sup- spaces that invited students to bring the artifacts,

ported development of the dispositions, knowledge, meanings, values, and resources of their home and

and skills needed to create classroom experiences community into the real work of classroom learning.

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 337 4/1/13 4:36 PM

KaiLonnie Dunsmore et al. | Rethinking Literacy Instruction through Community Mapping

page

338

Student engagement, learning, and achievement D. Hobson (Eds.), Teachers doing research

increased when home, community, and school liter- (pp. 173–191). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

acy routines were equally valued and legitimate. By Lytle, S., & Cochran-Smith, M. (1992). Teacher research

as a way of knowing. Harvard Education Review, 62,

asking students to bring in resources or stories from

447–475.

home or having them write about objects in their

Moll, L. (2010). Mobilizing culture, language, and

community, the students became deeply excited educational practices: Fulfilling the promises of

about classroom learning. And, significantly, in Mendez and Brown. Educational Researcher, 36,

a time of test scores and standards, as George 451–460.

tapped into previously dormant student interests Moll, L., & Gonzalez, N. (2004). Beginning where children

and experiences, they began to demonstrate strik- are. In O. Santa Maria (Ed.), Tongue-tied: The lives

ing improvements in their writing. Literacy became of multilingual children in public education

(pp. 134–151). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

personal and included the affective dimension of

Ordoñez-Jasis, R., & Jasis, P. (2011). Mapping literacy,

human experience that gives meaning to our liter-

mapping lives: Teachers exploring the sociopolitical

ate lives. George sums it up this way: “What I have context of literacy and learning. Multicultural

found to be incredibly important was the message I Perspectives, 13, 189–196.

was sending, more so than the words I was saying. Rowland Unified School District. (2008). Rowland Unified

I was letting students know that their worlds were School District Strategic Plan 2008-2013. Rowland

welcome in our classroom and relevant to our learn- Heights, CA: Author.

ing” (written reflections, 12/2011). Taylor, D. (2010). “I don’t want you to die in your entire

life. If you do I’ll bring you flowers”: Words in families

and word families at school. In K. Dunsmore &

References

D. Fisher (Eds.), Bringing literacy home (pp. 348–366).

Auerbach, E. (2001). Considering the multiliteracies Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

pedagogy: Looking through the lens of family literacy.

Tindle, K., Leconte, P., Buchanan, L., & Taymans, J.

In M. Kalantzis & B. Cope (Eds.), Transformation in

(2005). Transition planning: Community mapping

language and literacy: Perspectives on multiliteracies

as a tool for teachers and students. National Center

(pp. 99–112). Victoria, Australia: Common Ground.

on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSE),

Creswell, J. (2009). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Research to Practice Brief, 4(1). Retrieved from http://

Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, www.ncset.org/publications/viewdesc.asp?id=2128.

CA: SAGE.

Tredway, L. (2003). Community mapping: A rationale.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Unpublished manuscript prepared for the Principal

word and the world. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. Leadership Institute, University of California,

Gee, J. P. (1989). What is literacy? Journal of Education, Berkeley.

171, 18–25. Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of practice: Learning,

Hobson, D. (2001). Learning with each other: Collaboration meaning, and identity. Cambridge UK: Cambridge

in teacher research. In G. Burnaford, J. Fischer, & University Press.

KaiLonnie Dunsmore is the associate director of the National Center for Literacy Education and can be

reached at kdunsmore@ncte.org. Rosario Ordoñez-Jasis is a professor in the Department of Reading at

California State University, Fullerton and can be reached at rordonez@fullerton.edu. George Herrera is

is a Program Specialist at Giano Intermediate School and can be reached at gherrera@rowland.k12.ca.us.

These authors are active members of and contributors to the National Center for Literacy Education’s

Literacy in Learning Exchange community. Learn more about how their work in community mapping

is being scaled from one community of practiceto a districtwide (21 schools) initiative by going to

http://www.literacyinlearningexchange.org/community-mapping. There you can choose to follow

their group, listen to an archived webinar, read a vignette, or watch a video clip of participants

talking about their learning and work.

Language Arts, Volume 90 Number 5, May 2013

May2013_LA.indd 338 4/1/13 4:36 PM

You might also like

- Drama-Based PedagogyDocument13 pagesDrama-Based PedagogyKim Trishia BrulNo ratings yet

- Equity WalkDocument3 pagesEquity Walkapi-348938826No ratings yet

- Diversity Reflection: Library Lady, Solidified The Students' Ability To Make Connections To The Story. The Play WasDocument1 pageDiversity Reflection: Library Lady, Solidified The Students' Ability To Make Connections To The Story. The Play WasanynaoNo ratings yet

- Place-Based WritingDocument7 pagesPlace-Based Writingapi-279894036No ratings yet

- Heath What No Bed Time Stories Means 1982Document15 pagesHeath What No Bed Time Stories Means 1982Camila Mossi de QuadrosNo ratings yet

- Fun Poetry Activities - (Literacy Strategy Guide)Document12 pagesFun Poetry Activities - (Literacy Strategy Guide)Princejoy ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Meaningful Learning in The Co-Operative ClassroomDocument20 pagesMeaningful Learning in The Co-Operative ClassroomMadalina madaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of The Literacy Development PDFDocument6 pagesA Comparison of The Literacy Development PDFShiela AzoresNo ratings yet

- Arielle Francois Letter 1 Communication To A School Adminstrator 7Document4 pagesArielle Francois Letter 1 Communication To A School Adminstrator 7api-545474244No ratings yet

- Near Peer ESL Music ProjectDocument6 pagesNear Peer ESL Music ProjectKayli LiAnn LizarragaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Young Children's Learning Through Play Building Playful PedagogiesDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Young Children's Learning Through Play Building Playful PedagogiesKarla Salamero MalabananNo ratings yet

- EnhancingDocument17 pagesEnhancingJosephKiwasLlamido100% (1)

- Lesson Plan For 3 12 19Document5 pagesLesson Plan For 3 12 19api-458750555No ratings yet

- EJ1104033Document6 pagesEJ1104033Glennette AlmoraNo ratings yet

- Promoting Genre Awareness in The Efl Classroom PDFDocument14 pagesPromoting Genre Awareness in The Efl Classroom PDFGuillermina Schenk100% (1)

- Bialystok 1997Document12 pagesBialystok 1997veronicayhzNo ratings yet

- Educ 629 Capstone Essay PughDocument8 pagesEduc 629 Capstone Essay Pughapi-625229084No ratings yet

- Integrating Drama Into The ESLL ClassroomDocument8 pagesIntegrating Drama Into The ESLL Classroomraji letchumiNo ratings yet

- Language Arts Literacy 5 FinalDocument11 pagesLanguage Arts Literacy 5 Finalapi-346891460No ratings yet

- Poetry For Social StudiesDocument6 pagesPoetry For Social StudiesMichael SlechtaNo ratings yet

- TRTRDocument10 pagesTRTRapi-498787304No ratings yet

- Heath BedtimeStories PDFDocument14 pagesHeath BedtimeStories PDFLuizaNo ratings yet

- Sue Rogers and Julie Evans: 528 Inside Role-Play in Early Childhood Education: Researching Young Children's PerspectivesDocument3 pagesSue Rogers and Julie Evans: 528 Inside Role-Play in Early Childhood Education: Researching Young Children's Perspectivesmariana henteaNo ratings yet

- Arts Abled NetworkDocument4 pagesArts Abled NetworkTen Penny Players, IncNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity and Language Socialization in The Early YearsDocument2 pagesCultural Diversity and Language Socialization in The Early Yearsvaleria feyenNo ratings yet

- Article - Using Drama and Movement To Enhance English LiteracyDocument8 pagesArticle - Using Drama and Movement To Enhance English LiteracyDespina KalaitzidouNo ratings yet

- Reese 20 and 20 Cox 20 ArticleDocument10 pagesReese 20 and 20 Cox 20 ArticleClaudia Cristine CondriucNo ratings yet

- Romeo and JulietDocument69 pagesRomeo and Julietapi-291963732No ratings yet

- LAS q2 English9 Week1 v2Document7 pagesLAS q2 English9 Week1 v2Devon M. MasalingNo ratings yet

- w2 Assignment - Lesson PlansDocument5 pagesw2 Assignment - Lesson Plansapi-375889476No ratings yet

- Are Comics Effective Materials For Teaching EllsDocument12 pagesAre Comics Effective Materials For Teaching Ellsjavier_meaNo ratings yet

- TeachingMetaphorsL2Learners EJ Mar04Document7 pagesTeachingMetaphorsL2Learners EJ Mar04Hussain UmarNo ratings yet

- 6020 PaperDocument6 pages6020 Paperapi-310321083No ratings yet

- Using Storytelling in Teaching English in Palestinian Schools: Perceptions and DifficultiesDocument11 pagesUsing Storytelling in Teaching English in Palestinian Schools: Perceptions and DifficultieslananhctNo ratings yet

- 734-Article Text-2674-2-10-20201029Document20 pages734-Article Text-2674-2-10-20201029Yana ArsyadiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument12 pagesInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelNo ratings yet

- Multiple Ways of Knowing Multiple IntelligencesDocument5 pagesMultiple Ways of Knowing Multiple IntelligencesTomas MongeNo ratings yet

- King-1979-Play-The Kindergartners PerspectiveDocument8 pagesKing-1979-Play-The Kindergartners PerspectiveSonia AssuncaoNo ratings yet

- Authentic Literacy Activities For Developing ComprDocument13 pagesAuthentic Literacy Activities For Developing ComprSushiQNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Voices MatterDocument8 pagesIndigenous Voices Matterapi-541684013No ratings yet

- International Journal of Education & The Arts: EditorsDocument21 pagesInternational Journal of Education & The Arts: EditorsAskhianur YashifaNo ratings yet

- My Heart Fills With Happiness Class Book LessonDocument4 pagesMy Heart Fills With Happiness Class Book Lessonapi-515904770No ratings yet

- El Ed 122 Pedagogical Implications LectureDocument5 pagesEl Ed 122 Pedagogical Implications Lecturemtkho1909No ratings yet

- Pedagogical Implication of Teaching Literature in ElementaryDocument5 pagesPedagogical Implication of Teaching Literature in ElementaryRENATO JR. RARUGALNo ratings yet

- Neesha Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesNeesha Lesson Planapi-662165409No ratings yet

- Classroom Observation Analysis Yates Ted621aDocument10 pagesClassroom Observation Analysis Yates Ted621aapi-463766485No ratings yet

- Moje 2004Document33 pagesMoje 2004freyaSydNo ratings yet

- They Called Us EnemyDocument2 pagesThey Called Us Enemygina.ebron1No ratings yet

- GenreRelations MartinRose 2007 PDFDocument258 pagesGenreRelations MartinRose 2007 PDFlalau2248100% (4)

- Vonnahme Master's Portfolio 1Document8 pagesVonnahme Master's Portfolio 1api-742989488No ratings yet

- Teaching Literature AppreciationDocument6 pagesTeaching Literature AppreciationRalph Samuel VillarealNo ratings yet

- Drawings As Imaginative Expressions of Philosophical Ideas in A Grade 2 South African Literacy ClassroomDocument11 pagesDrawings As Imaginative Expressions of Philosophical Ideas in A Grade 2 South African Literacy Classroomrowaida quraishNo ratings yet

- Invitations To LearnDocument5 pagesInvitations To Learnapi-26876268No ratings yet

- Teaching English To Young ChildrenDocument9 pagesTeaching English To Young ChildrenLyuda KMNo ratings yet

- READING 1.2 - Jehangir-2012-About - CampusDocument7 pagesREADING 1.2 - Jehangir-2012-About - Campusaryanrana20942No ratings yet

- Kindergarten: A Teacher, Her Students, and a Year of LearningFrom EverandKindergarten: A Teacher, Her Students, and a Year of LearningRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Effective Use of Children's Literature For Esl - Efl Young LearnersDocument14 pagesEffective Use of Children's Literature For Esl - Efl Young LearnersMicaela MunizNo ratings yet

- Lena Archer Jarred Wenzel Curriculum Ideology AssignmentDocument9 pagesLena Archer Jarred Wenzel Curriculum Ideology Assignmentapi-482428947No ratings yet

- School Community Connections For OtlDocument33 pagesSchool Community Connections For OtlDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Spaceredesignimpossibilities Amini NgabonzizaJ.2015Document11 pagesSpaceredesignimpossibilities Amini NgabonzizaJ.2015Deisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Seeing Student LearningDocument13 pagesSeeing Student LearningDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Teachers Reinterpretations of Critical Literacy Policy Prioritizing PraxisDocument29 pagesTeachers Reinterpretations of Critical Literacy Policy Prioritizing PraxisDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Teachers StruggleDocument19 pagesTeachers StruggleDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Seeing and Hearing Students Lived and Embodied Critical Literacy PracticesDocument9 pagesSeeing and Hearing Students Lived and Embodied Critical Literacy PracticesDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Critical Literacy in The EFL Classroom: Evolving Multiple Perspectives Through Learning TasksDocument30 pagesCritical Literacy in The EFL Classroom: Evolving Multiple Perspectives Through Learning TasksErdinc UlgenNo ratings yet

- Aveling, E.-L., Gillespie, A., & Cornish, F. (2014) - A Qualitative Method For Analysing Multivoicedness PDFDocument18 pagesAveling, E.-L., Gillespie, A., & Cornish, F. (2014) - A Qualitative Method For Analysing Multivoicedness PDFM Deisy PatoNo ratings yet

- Educators Perspectives On Supporting Student AgencyDocument11 pagesEducators Perspectives On Supporting Student AgencyDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Cultivating Teacher Candidates Who Support Student Agency Four Promising PracticesDocument11 pagesCultivating Teacher Candidates Who Support Student Agency Four Promising PracticesDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Bakhtinian Dialogic Concept in Language Learning Process PDFDocument6 pagesBakhtinian Dialogic Concept in Language Learning Process PDFM Deisy PatoNo ratings yet

- Bubb - Student Voice To Improve Schools - Final Resubmission 20122019Document21 pagesBubb - Student Voice To Improve Schools - Final Resubmission 20122019Deisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Cook Sather 2020Document24 pagesCook Sather 2020Deisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Agency As Collectivity Community Based Research For Educational EquityDocument12 pagesAgency As Collectivity Community Based Research For Educational EquityDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Students-As-Producers: Developing Valuable Student-Centered Research and Learning OpportunitiesDocument15 pagesStudents-As-Producers: Developing Valuable Student-Centered Research and Learning OpportunitiesDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Gunter2007 Where Are The ChildrenDocument6 pagesGunter2007 Where Are The ChildrenDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Futurelab: Learner Voice Handbook: Tim Rudd, Fiona Colligan, Rajay NaikDocument40 pagesFuturelab: Learner Voice Handbook: Tim Rudd, Fiona Colligan, Rajay NaikDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Edug 621 Listeningtopupilsvoices2010Document23 pagesEdug 621 Listeningtopupilsvoices2010Vassiliki Amanatidou-KorakaNo ratings yet

- Students As Researchers Making A DiffereDocument76 pagesStudents As Researchers Making A DiffereDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Children's Voices:: Pupil Leadership in Primary SchoolsDocument35 pagesChildren's Voices:: Pupil Leadership in Primary SchoolsDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Recognizing The Pedagogy of Voice in A Learning Community: Stewart RansonDocument17 pagesRecognizing The Pedagogy of Voice in A Learning Community: Stewart RansonDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Pupil Voice Is Here To Stay!Document2 pagesPupil Voice Is Here To Stay!Deisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Bishop - Critical Literacy PDFDocument13 pagesBishop - Critical Literacy PDFΝεκτάριοςΜποσμήςNo ratings yet

- From What Is Reading To What Is Literacy PDFDocument11 pagesFrom What Is Reading To What Is Literacy PDFDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Critical Literacy in Teaching and Research1 PDFDocument19 pagesCritical Literacy in Teaching and Research1 PDFDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Communities of Caring Developing Curriculum That Engages Latino A Students Diverse Literacy Practices PDFDocument12 pagesCommunities of Caring Developing Curriculum That Engages Latino A Students Diverse Literacy Practices PDFDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- Coaching Literacy Teachers As They Design Critical Literacy Practices PDFDocument22 pagesCoaching Literacy Teachers As They Design Critical Literacy Practices PDFDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- HTTP Www3.Indiaresults - Com Rajasthan Uor 2010 BEd Roll ResultDocument2 pagesHTTP Www3.Indiaresults - Com Rajasthan Uor 2010 BEd Roll Resultdinesh_nitu2007No ratings yet

- Eng6 Q1 Las6Document6 pagesEng6 Q1 Las6Mark Delgado RiñonNo ratings yet

- Parental ConsentDocument2 pagesParental ConsentHae Rol DeeNo ratings yet

- New ResumeDocument2 pagesNew Resumeapi-285225051No ratings yet

- First Grade Science Seasons LessonDocument10 pagesFirst Grade Science Seasons Lessonapi-273149494100% (2)

- Philo Long Test 1Document2 pagesPhilo Long Test 1Nastasia BesinNo ratings yet

- BehaviourDocument4 pagesBehaviourapi-547203445No ratings yet

- JHS Class Program S.Y. 2021 2022 SchoolDocument26 pagesJHS Class Program S.Y. 2021 2022 SchooljunapoblacioNo ratings yet

- Cat2 LessonDocument10 pagesCat2 Lessonapi-351315587No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: AppellantDocument236 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: AppellantEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Patrick Henry Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPatrick Henry Lesson Planapi-273911894No ratings yet

- Graduation ScriptDocument6 pagesGraduation ScriptZenmar Luminarias GendiveNo ratings yet

- Paddy Damschen Memorial Scholarship Fund GuidelinesDocument2 pagesPaddy Damschen Memorial Scholarship Fund GuidelinesRyan DamschenNo ratings yet

- Theories of Assertive TacticsDocument24 pagesTheories of Assertive TacticsNursha- Irma50% (2)

- Vaishnavi KaleDocument1 pageVaishnavi KaleVedant MankarNo ratings yet

- Madriaga, Rona Frances A.Document6 pagesMadriaga, Rona Frances A.Jason L. Saldua,BSN,RNNo ratings yet

- Carter B. Gomez, RME, MSIT: EducationDocument2 pagesCarter B. Gomez, RME, MSIT: EducationGhlends Alarcio GomezNo ratings yet

- ANSCOMBE On Brute Facts PDFDocument5 pagesANSCOMBE On Brute Facts PDFadikarmikaNo ratings yet

- Courtney Conway - Lesson Plan 1Document5 pagesCourtney Conway - Lesson Plan 1api-484951827No ratings yet

- AbsurdityDocument10 pagesAbsurdityBerkay TuncayNo ratings yet

- Organizational Development: Foundation OD Process Intervention Techniques Ethics PoliticsDocument25 pagesOrganizational Development: Foundation OD Process Intervention Techniques Ethics PoliticsRama NathanNo ratings yet

- Lac Mass Leadership Reflection EssayDocument3 pagesLac Mass Leadership Reflection Essayapi-270432871No ratings yet

- Qc&qa AbkDocument22 pagesQc&qa Abkdosetiadi100% (1)

- Artikel Widyawati JPN - TransDocument12 pagesArtikel Widyawati JPN - TransAkhmad Edwin Indra PratamaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Module 4Document16 pagesAssignment Module 4saadia khanNo ratings yet

- The NDA and The IMA...Document18 pagesThe NDA and The IMA...Frederick NoronhaNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast EssayDocument4 pagesCompare and Contrast EssayelmoatassimNo ratings yet

- Capstone Research Paper FinalDocument5 pagesCapstone Research Paper Finalapi-649891869No ratings yet

- RecommendationDocument1 pageRecommendationAyush KumarNo ratings yet

- Validacao Escala Espiritualidade Pinto - Pais RibeiroDocument7 pagesValidacao Escala Espiritualidade Pinto - Pais RibeiroLucasFelipeRibeiroNo ratings yet