Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Importance of Standard The Fictitious Person

Uploaded by

Samuel Walsh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views2 pagesobli

Original Title

p6

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentobli

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views2 pagesImportance of Standard The Fictitious Person

Uploaded by

Samuel Walshobli

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Importance of Standard

The Fictitious Person

Picart v. Smith, 1918 — An automobile hit a horseman, who was on the wrong side of the road. The horseman thought he

did not have time to get to the other side. The car passed by too close that the horse turned its body across, with its head

toward the railing. Its limb was broken, and its rider was thrown off and injured. The SC found the automobile driver negligent,

since a prudent man should have foreseen the risk in his course and that he had the last fair chance to avoid the harm.

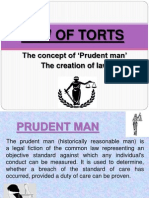

Doctrine: The test to determine the existence of negligence in a particular case is: Did the defendant in doing the alleged

negligent act use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily prudent person would have used in the same situation?

The law here in effect adopts the standard suppose to be supplied by the imaginary conduct of the discreet paterfamilias of the

Roman law. The existence of negligence in a given case is not determined by reference to the personal judgment of the actor in

the situation before him. The law considers what would be reckless, blameworthy, or negligent in the man of ordinary

intelligence and prudence and determines liability by that.

Notes: The Picart test is the most cited test of negligence. It introduced the use of the fictitious person. It has the markings of

common law but because it uses the concept of the discreet paterfamilias, later enshrined in the Civil Code as the good father of

a family, it is now a civil law test.

Sicam v. Jorge, 2007 — Jorge pawned jewelry with Agencia de R. C. Sicam. Armed men entered the pawnshop and took away

cash and jewelry from the pawnshop vault. Jorge demanded the return of the jewelry. The pawnshop failed. The SC held Sicam

liable for failing to employ sufficient safeguards for the pawned goods. It held that robbery, if negligence concurred, is not a

fortuitous event. Also, Article 2099 requires a creditor to take care of the thing pledged with the diligence of a good father of a

family.

Doctrine: The diligence with which the law requires the individual at all times to govern his conduct varies with the nature of

the situation in which he is placed and the importance of the act which he is to perform. Negligence, therefore, is the omission

to do something which a reasonable man, guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human

affairs, would do; or the doing of something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. It is want of care required by

the circumstances.

Notes: The fictitious person is not the standard. It is his conduct.

Corinthian Gardens v. Tanjangco, 2008 — The Cuasos built their house on a lot adjoining that owned by the Tanjangcos.

Their plan was approved by Corinthian Gardens. It turned out, however, that the house built encroached on the lot of the

Tanjangcos. The SC found Corinthian Gardens negligent for conducting only "table inspections," when it should have conducted

actual site inspections, which could have prevented the encroachment.

Doctrine: A negligent act is an inadvertent act; it may be merely carelessly done from a lack of ordinary prudence and may be

one which creates a situation involving an unreasonable risk to another because of the expectable action of the other, a third

person, an animal, or a force of nature. A negligent act is one from which an ordinary prudent person in the actor's position, in

the same or similar circumstances, would foresee such an appreciable risk of harm to others as to cause him not to do the act or

to do it in a more careful manner.

Notes: The test cited in the case was the Picart test.

Special Circumstances

Heirs of Completo v. Albayda, 2010 — Albayda, Master Sergeant in the Philippine Air Force, was at an intersection riding his

bike when he was hit by a taxi driven by Completo. Albayda suffered injuries, including breaking his knee. The SC found

Completo negligent, since he was overspeeding when he reached the intersection. Also, the bike already had the right of way at

the time of the incident.

Doctrine: The bicycle occupies a legal position that is at least equal to that of other vehicles lawfully on the highway, and it is

fortified by the fact that usually more will be required of a motorist than a bicyclist in discharging his duty of care to the other

because of the physical advantages the automobile has over the bicycle.

Notes: The witnesses for the same parties are of the same number. It seems odd, therefore, to apply the test of negligence

when the facts are not settled by preponderance of evidence. Thus, it appears that the court sympathized with Albayda, who

was serving the government and was left by his wife, supposedly because of his injuries.

Pacis v. Morales, 2010 — Morales owned a gun shop. An employee of the shop allowed Pacis to inspect a gun brought in for

repair. It turned out that the gun was loaded and when Pacis laid it down, it discharged a bullet, hitting his head. He died. The

SC found Morales, as the owner, liable, since he failed to exercise the diligence required of a good father of a family, much less

that required of someone dealing with dangerous weapons.

Doctrine: A higher degree of care is required of someone who has in his possession or under his control an instrumentality

extremely dangerous in character, such as dangerous weapons or substances. Such person in possession or control of

dangerous instrumentalities has the duty to take exceptional precautions to prevent any injury being done thereby. Unlike the

ordinary affairs of life or business which involve little or no risk, a business dealing with dangerous weapons requires the

exercise of a higher degree of care.

Notes: Two things may be considered negligent: the keeping of a defective gun loaded and the storing a defective gun in a

drawer. It is strange, however, that the negligence of the employee was not discussed, when the presumption that the

employer was negligent only arises after the negligence of the employee is established. Also, that the wound sustained was in

the head appears to be a factual anomaly.

Children

Taylor v. Manila Railroad, 1910 — David Taylor, 15 years old, and Manuel, 12, obtained fulminating caps from the

compound of Manila Railroad. They experimented on them. The experiment ended with a bang, literally. The explosion caused

injury to the right eye of Taylor. His father sued for damages. The defense of Manila Railroad is the entry to their compound

was without its invitation. The SC held that the absence of invitation cannot relieve Manila Railroad from liability. However, it

held that the proximate cause of the injury was Taylor's negligence.

Doctrine: The personal circumstances of the child may be considered in determining the existence of negligence on his part.

You might also like

- The Law of Torts: A Concise Treatise on the Civil Liability at Common Law and Under Modern Statutes for Actionable Wrongs to PersonFrom EverandThe Law of Torts: A Concise Treatise on the Civil Liability at Common Law and Under Modern Statutes for Actionable Wrongs to PersonNo ratings yet

- PBL LEGAL TEAM (2)Document15 pagesPBL LEGAL TEAM (2)Adham MohsinNo ratings yet

- Doctrine:: Petitioners May Institute Separate Civil Action To Recover DamagesDocument5 pagesDoctrine:: Petitioners May Institute Separate Civil Action To Recover DamagesLeo GarciaNo ratings yet

- Rise of the Oathbreakers Part 2: America's Crisis of Competency in Law EnforcementFrom EverandRise of the Oathbreakers Part 2: America's Crisis of Competency in Law EnforcementNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages WEEK 1Document6 pagesTorts and Damages WEEK 1shamymyNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument14 pagesLaw of TortsNeha GillNo ratings yet

- PVL 3703Document6 pagesPVL 3703corymamkNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-Negligence-In-GeneralDocument14 pagesChapter 2-Negligence-In-GeneralailynvdsNo ratings yet

- Schmidt v. United States and Seven Other Cases, 179 F.2d 724, 10th Cir. (1950)Document9 pagesSchmidt v. United States and Seven Other Cases, 179 F.2d 724, 10th Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort Negligence AssignmentDocument10 pagesLaw of Tort Negligence AssignmenthammadjmiNo ratings yet

- Law of TortDocument7 pagesLaw of Tortokidirichard220No ratings yet

- BONILLATorts and Damages - Midterm ExamDocument10 pagesBONILLATorts and Damages - Midterm ExamHannah BonillaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Damage summaryDocument7 pagesCriminal Damage summaryMuhammad Raees MalikNo ratings yet

- TORTS - STANDARD OF CONDUCT With CasesDocument12 pagesTORTS - STANDARD OF CONDUCT With CasesJULIE MORALESNo ratings yet

- Culpa vs. DoloDocument3 pagesCulpa vs. DoloJake Bolante90% (10)

- Negligence Negligence in Special Cases (Children)Document19 pagesNegligence Negligence in Special Cases (Children)PhilipBrentMorales-MartirezCariagaNo ratings yet

- Egrees OF EgligenceDocument2 pagesEgrees OF EgligenceSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Accident: Accident Lawful Act in A Lawful Manner Proper Care and CautionDocument3 pagesAccident: Accident Lawful Act in A Lawful Manner Proper Care and CautionSyasya FatehaNo ratings yet

- Lect. 2 Actus Reus - Elements of A Crime - PDF-WT - SummariesDocument3 pagesLect. 2 Actus Reus - Elements of A Crime - PDF-WT - SummariesjxsxnblxckNo ratings yet

- Torts IIDocument12 pagesTorts IIWhitney E. TillmanNo ratings yet

- Negligence liability and elements of tortsDocument4 pagesNegligence liability and elements of tortsgurL23No ratings yet

- TOPIC 2 General DefencesDocument6 pagesTOPIC 2 General DefencesBenjamin BallardNo ratings yet

- DigestDocument4 pagesDigestailynvdsNo ratings yet

- Actus ReusDocument7 pagesActus ReusSaffah Mohamed0% (1)

- Picart v. SmithDocument1 pagePicart v. SmithNichole LanuzaNo ratings yet

- As Law Model Answers Lp1Document3 pagesAs Law Model Answers Lp1Anastasia TsiripidouNo ratings yet

- PFR Module 1 Case Summary From MyLegalwhiz CompiledDocument57 pagesPFR Module 1 Case Summary From MyLegalwhiz CompiledRachell Ann UsonNo ratings yet

- Palsgraf vs. Long Island Rail Company - PDFDocument18 pagesPalsgraf vs. Long Island Rail Company - PDFVina CagampangNo ratings yet

- 13 Layugan v. IACDocument2 pages13 Layugan v. IACRaya Alvarez TestonNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts I Life SaverDocument9 pagesLaw of Torts I Life SaverHadi Onimisi TijaniNo ratings yet

- Turezyn Torts Final OutlineDocument33 pagesTurezyn Torts Final OutlineJun Ma100% (1)

- Capacity of Parties in Law of TortsDocument8 pagesCapacity of Parties in Law of TortsUtkarsh SachoraNo ratings yet

- NPC Vs CA Until Phoenix Vs IACDocument24 pagesNPC Vs CA Until Phoenix Vs IACOleksandyr UsykNo ratings yet

- Abrogar Vs COSMOSDocument37 pagesAbrogar Vs COSMOSJigs JiggalowNo ratings yet

- Del Carmen v. Bacoy 25 April 2012Document22 pagesDel Carmen v. Bacoy 25 April 2012dorothy annNo ratings yet

- 12 Hedy Gan Vs CADocument1 page12 Hedy Gan Vs CACollen Anne PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument3 pagesCase DigestsFrancein CequenaNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort NegligenceDocument20 pagesLaw of Tort NegligenceSophia AcquayeNo ratings yet

- Mental Elements in Tortious LiabilityDocument5 pagesMental Elements in Tortious Liabilityricha ayengiaNo ratings yet

- PDF Document 8Document34 pagesPDF Document 8Davia ShawNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document9 pagesUnit 3danish akhtarNo ratings yet

- Torts ReviewerDocument48 pagesTorts ReviewerEricson AquinoNo ratings yet

- PPL 311 Law of Torts-1Document66 pagesPPL 311 Law of Torts-1Emmanuel Light100% (4)

- Law of Tort NotesDocument15 pagesLaw of Tort NotesfmsaidNo ratings yet

- 001 DIGESTED Amado Picart Vs Frank Smith - G.R. No. L-12219Document4 pages001 DIGESTED Amado Picart Vs Frank Smith - G.R. No. L-12219Paul ToguayNo ratings yet

- Oscar Jr. Liable for Fatal Jeep AccidentDocument4 pagesOscar Jr. Liable for Fatal Jeep AccidentAB100% (1)

- Law Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050Document4 pagesLaw Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050udit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Delict Omissions HandoutDocument6 pagesDelict Omissions HandoutRendaniNo ratings yet

- Picart Vs SmithDocument2 pagesPicart Vs SmithElay CalinaoNo ratings yet

- Elibrarydatafile Justification of TortsDocument10 pagesElibrarydatafile Justification of TortsAbhi TripathiNo ratings yet

- Negligence and Strict Liability. Notes PDFDocument58 pagesNegligence and Strict Liability. Notes PDFWangalya EdwinNo ratings yet

- STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION Sample QuestionsDocument4 pagesSTATUTORY CONSTRUCTION Sample QuestionsAw Ds Qe100% (1)

- Torts CasesDocument13 pagesTorts CasesAprille S. AlviarneNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages BedaDocument31 pagesTorts and Damages BedaAnthony Rupac Escasinas100% (16)

- Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious LiabilityDocument4 pagesCh. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liabilitykumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Picart V SmithDocument3 pagesPicart V SmithFrancein CequenaNo ratings yet

- Law AssignmentDocument7 pagesLaw AssignmentJING WEI LOHNo ratings yet

- Legal Environment of Business 13th Edition Meiners Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesLegal Environment of Business 13th Edition Meiners Solutions Manual 1josedavidsonqjnxrdokam100% (22)

- Search and Seizure 4Document1 pageSearch and Seizure 4Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure 8Document2 pagesSearch and Seizure 8Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Calamba Medical vs. NLRCDocument2 pagesCalamba Medical vs. NLRCSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Whether Respondents Are Regular Employees of Hacienda Maasin and Thus Entitled To Their Monetary ClaimsDocument1 pageWhether Respondents Are Regular Employees of Hacienda Maasin and Thus Entitled To Their Monetary ClaimsSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure 1Document2 pagesSearch and Seizure 1Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure 2Document3 pagesSearch and Seizure 2Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure 3Document1 pageSearch and Seizure 3Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure 5Document3 pagesSearch and Seizure 5Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Century Properties vs. BabianoDocument1 pageCentury Properties vs. BabianoSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Calamba Medical vs. NLRCDocument2 pagesCalamba Medical vs. NLRCSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Labstan 3Document2 pagesLabstan 3Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Girlie M. Quisay v. People of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesGirlie M. Quisay v. People of The PhilippinesSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Employee dismissal rights and responsibilitiesDocument2 pagesEmployee dismissal rights and responsibilitiesSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Of Appeals,: Two-Tiered TestDocument2 pagesOf Appeals,: Two-Tiered TestSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Labstan 4Document2 pagesLabstan 4Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Labstan 1Document2 pagesLabstan 1Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Corpuz v. People PhilippinesDocument2 pagesCorpuz v. People PhilippinesSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Resolve The Motion With Reasons. (4%) : Suggested AnswerDocument1 pageResolve The Motion With Reasons. (4%) : Suggested AnswerSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Crimpro 6Document2 pagesCrimpro 6Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 169004Document3 pagesG.R. No. 169004Samuel Walsh100% (1)

- Into Account Its Nature and Surrounding Circumstances.: 3 AmendmentsDocument2 pagesInto Account Its Nature and Surrounding Circumstances.: 3 AmendmentsSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Strait vs. Secretary Angelo ReyesDocument6 pagesStrait vs. Secretary Angelo ReyesSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Dungo, Et Al v. PeopleDocument4 pagesDungo, Et Al v. PeopleSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answer:: Information Amendment Supervening Events (1997)Document3 pagesSuggested Answer:: Information Amendment Supervening Events (1997)Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answer:: Bail Application Venue (2002)Document2 pagesSuggested Answer:: Bail Application Venue (2002)Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answer: No. The Aggravating Circumstance of Unlawful Entry in The Complainant's Abode Has To Be Specified in TheDocument1 pageSuggested Answer: No. The Aggravating Circumstance of Unlawful Entry in The Complainant's Abode Has To Be Specified in TheSamuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answer:: When A Criminal Case Is Dismissed On Nolle Prosequi, Can It Later Be Refilled?Document2 pagesSuggested Answer:: When A Criminal Case Is Dismissed On Nolle Prosequi, Can It Later Be Refilled?Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Bail Matter of Right vs. Matter of Discretion (2006)Document2 pagesBail Matter of Right vs. Matter of Discretion (2006)Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Arrest Warrantless Arrests Objection (2000)Document2 pagesArrest Warrantless Arrests Objection (2000)Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Crimpro 1Document2 pagesCrimpro 1Samuel WalshNo ratings yet

- Law Thesis: Adv. Nadirshaw K. DhondyDocument29 pagesLaw Thesis: Adv. Nadirshaw K. DhondyShilpa JainNo ratings yet

- The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937Document4 pagesThe Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937Kishore KumarNo ratings yet

- R.a.9520 (Presentation)Document42 pagesR.a.9520 (Presentation)Marlon EspedillonNo ratings yet

- 3 IOD Judgement Copy WC+Case+Francis+D+CostaDocument12 pages3 IOD Judgement Copy WC+Case+Francis+D+Costajustbase3225No ratings yet

- Case Digests Bar ExamsDocument7 pagesCase Digests Bar Examsshaieeeeee0% (1)

- 13feb01 MinDocument3 pages13feb01 MinwilliamblueNo ratings yet

- Department of EducationDocument7 pagesDepartment of EducationSto. Rosario ES (R III - Pampanga)No ratings yet

- GV101 Week 13: Regimes, Executives and Policy-MakingDocument32 pagesGV101 Week 13: Regimes, Executives and Policy-MakingAayush PuriNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudySanny DanNo ratings yet

- Cases of Misconduct by Judge James P. Fisher FINALDocument10 pagesCases of Misconduct by Judge James P. Fisher FINALLowell FeldNo ratings yet

- Ang Pue v. Sec. of Commerce and Industry, 5 SCRA 645Document1 pageAng Pue v. Sec. of Commerce and Industry, 5 SCRA 645Aphrobit CloNo ratings yet

- Cause of Action For Conversion of PropertyDocument3 pagesCause of Action For Conversion of PropertyGee PennNo ratings yet

- Court OrderDocument2 pagesCourt OrderHarold HugginsNo ratings yet

- Legal Education in BangladeshDocument14 pagesLegal Education in BangladeshSuvrajyoti GuptaNo ratings yet

- MR Ashwin ValwanDocument1 pageMR Ashwin ValwanVivek DixitNo ratings yet

- Delays and Disruptions Under FIDIC 1992Document3 pagesDelays and Disruptions Under FIDIC 1992arabi1No ratings yet

- Health Policies and PoliticsDocument27 pagesHealth Policies and Politicsapi-546749920No ratings yet

- The Hague Peace and JusticeDocument15 pagesThe Hague Peace and JusticeAnonymous c9XNwrQNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. Bartolome Tampus and Ida Montesclaros, Defendants. IDA MONTESCLAROS, AppellantDocument35 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. Bartolome Tampus and Ida Montesclaros, Defendants. IDA MONTESCLAROS, AppellantPreciousNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionDocument11 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionGermaine CarreonNo ratings yet

- Beneco Vs Ferrer-CallejaDocument4 pagesBeneco Vs Ferrer-CallejaKhein AnggacoNo ratings yet

- Pari delicto doctrine prevents relief for parties equally at faultDocument4 pagesPari delicto doctrine prevents relief for parties equally at faultMae NavarraNo ratings yet

- St. Martin's Funeral Homes v. NLRCDocument1 pageSt. Martin's Funeral Homes v. NLRCIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Special Contracts ProjectDocument12 pagesSpecial Contracts Projectabhilasha mehtaNo ratings yet

- Lavers (2010) Early Termination by Client in Event of Contractor's Non-PerformanceDocument30 pagesLavers (2010) Early Termination by Client in Event of Contractor's Non-PerformanceKasun DulanjanaNo ratings yet

- RTI - Hydraulic Engineer - 03 - E04Document3 pagesRTI - Hydraulic Engineer - 03 - E04akash narNo ratings yet

- Divorce Case DigestsDocument13 pagesDivorce Case DigestsCoreyCalandadaNo ratings yet

- Credit Digests START TO FINALSDocument80 pagesCredit Digests START TO FINALSDavid YapNo ratings yet

- Manifest Ambition James K. PolkDocument241 pagesManifest Ambition James K. PolkNataniel GallardoNo ratings yet

- MMPCI vs Linsangan: Agency and Contract DisputeDocument12 pagesMMPCI vs Linsangan: Agency and Contract DisputeOwen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet