Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MOHR, Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels - A Theoretical Perspective

Uploaded by

Katerina MarxtovaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MOHR, Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels - A Theoretical Perspective

Uploaded by

Katerina MarxtovaCopyright:

Available Formats

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels: A Theoretical Perspective

Author(s): Jakki Mohr and John R. Nevin

Source: Journal of Marketing , Oct., 1990, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Oct., 1990), pp. 36-51

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of American Marketing Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/1251758

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Inc. and American Marketing Association are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Marketing

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Jakki Mohr & John R. Nevin

Communication Strategies

in Marketing Channels:

A Theoretical Perspective

Though the marketing literature acknowledges that communication plays a vital role in chann

tioning, it provides no integrated theory for channel communication. The authors build a theoretical m

to help understand the role of communication in marketing channels. They propose a contingenc

in which communication strategy moderates the impact of channel conditions (structure, clim

power) on channel outcomes (coordination, satisfaction, commitment, and performance). When

munication strategy matches the channel conditions, channel outcomes will be enhanced in com

with the outcomes when a communication strategy mismatches channel conditions.

OMMUNICATION can be described as the glue out of the decision-making process on programs that

that holds together a channel of distribution. Thedirectly affect their businesses (Cooper 1988). Deal-

role of communication within marketing channels isers say that by involving them in planning and by so-

an important issue from both a managerial and a the-liciting their input, manufacturers could overcome this

oretical perspective. Communication in marketing problem (which dealers say is caused by manufactur-

channels can serve as the process by which persuasiveers who issue one-way directives). Additionally, Et-

information is transmitted (Frazier and Summers 1984), gar (1979, p. 65) suggests that conflict is caused by

participative decision making is fostered (Anderson, ineffective communication, which leads to "misun-

Lodish, and Weitz 1987), programs are coordinated derstandings, incorrect strategies, and mutual feelings

(Guiltinan, Rejab, and Rodgers 1980), power is ex-of frustration."

ercised (Gaski 1984), and commitment and loyalty are The lack of relevant theoretical and empirical re-

encouraged. search on channel communication makes it difficult

The managerial importance stems from the fact that to suggest effective and efficient communication strat-

communication difficulties are a prime cause of chan-egies for channel managers. Current heuristics and rules

nel problems. Many current problems in dealer chan-of thumb-such as "more communication," "im-

nels could be resolved by developing appropriateproved communication," and "open communication"

strategies for communication between manufacturers(cf. Eliashberg and Michie 1984)-that are proferred

and resellers. For instance, a recent problem cited by

for channel management are not only simplistic but

computer dealers is that dealers feel they are being left probably inaccurate. For instance, if distrust or con-

flict is present between channel members, the call for

open communication may be deleterious to the rela-

Jakki Mohr is Assistant Professor of Marketing, College of Business and

Administration, University of-Colorado, Boulder. John R. Nevin is Grain-tionship if the open communication conveys threats or

ger Wisconsin Distinguished Professor, Graduate School of Business, other forms of coercive power.

University of Wisconsin-Madison. The authors gratefully acknowledge Though the marketing literature acknowledges that

the insightful comments of James Dillard, Associate Professor of Com-

communication plays a vital role in channel function-

munication Arts, and Anne Miner, Assistant Professor of Management,

ing (Grabner and Rosenberg 1969; Stern and El-An-

University of Wisconsin-Madison, as well as the helpful suggestions

from anonymous JM reviewers. sary 1988), it provides no integrated theory for chan-

nel communication. Communication has been linked

36 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Churchill 1984).2 The first step (as shown in Fig-

conceptually to both structural issues (e.g., the pattern

of exchange relationships) and behavioral issues (e.g.,

ure 1) consists of the impact of channel conditions on

power and climate) in the channel, yet empirical re- qualitative outcomes such as satisfaction, whereas the

search on channel communication is sparse. The role second step links the qualitative outcomes to quanti-

of channel communication as a moderator between tative outcomes such as performance. Thus, the im-

structural/behavioral conditions and channel out- pact of the interaction between channel conditions and

comes (e.g., channel member coordination, satisfac-communication strategy on outcomes also may be a

tion, commitment levels, and performance) has been two-step process.

largely ignored by marketing academicians. After we more fully develop facets of communi-

For example, the literature has not acknowledged cation, we discuss the relationships between the facets

the moderating role of channel communication when of communication and the various channel conditions.

linking the following channel conditions' to channel The implicit assumption in developing the ties be-

outcomes: tighter contractual relationships to higher tween channel conditions and communication facets

performance (Reve and Ster 1986), the use of power is that no interactions occur between channel condi-

sources to dealer satisfaction and performance (Gaski tions. We define combinations of the facets of com-

and Nevin 1985), and climate to satisfaction levels munication as communication strategies, then explore

(Schul, Little, and Pride 1985). The process by which the channel outcome implications of channel condi-

these linkages between channel conditions and chan- tions and communication strategies. Next, we relax

nel outcomes occur is communication-the tool by the initial assumption of no interactions and examine

which channel structure is implemented (Brown 1981), the effect of interactions on communication strategy.

climate is expressed (Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz Finally, we discuss the managerial implications and

1987), and power is exercised (Gaski 1984). offer suggestions for future research.

The major purpose of our article is to address the

gap in channel theory, both in understanding channel

Facets of Communication

communication and in prescribing communication

strategies. By using organizational theories and re- The two bodies of knowledge that guide development

search, as well as communication theories and. re- of our model for channel communication are organi-

search, we build a model for channel communication. zational theory and communications theory. These

This model can be used to draw managerial implica-theories not only guide the selection of the facets of

communication for the model, but also ground the de-

tions that go beyond the simple rules of thumb cur-

velopment of the underlying theory for the model.

rently in use and that more accurately reflect the di-

versity of a channel setting. Moreover, the model The facets of communication we explore come from

specifies how communication can be used to attain the mechanistic perspective of communication theory

enhanced levels of channel outcomes. (Krone, Jablin, and Putnam 1987), in which com-

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the modelmunication is viewed as a transmission process through

of channel communication developed here. As showna channel (mode). Important facets of the communi-

in the figure, the model explores communication fac-cation process include the message (content), the

ets of frequency, direction, modality, and content; channel (mode), feedback (bidirectional communica-

channel conditions of structure, climate, and power;tion), and communication effects. Furthermore, the

and channel outcomes of coordination, satisfaction, message is concrete and has properties of frequency

commitment, and performance. We develop a contin- and/or duration.3

gency theory in which the level of channel outcomes We note parenthetically that communication has

obtained is contingent upon interaction between com-

munication strategy and given channel conditions. To

the extent that these specific combinations of com- 2However, other literature bases, including the sales management

munication facets match the extant channel condi- literature and two articles from organizational communication, indi-

cate a different type of process. The sales management literature

tions, channel outcomes will be enhanced. (Bagozzi 1980) suggests that performance affects the level of satis-

The channels literature suggests that channel out- faction (rather than the reverse). The articles in organizational com-

munication suggest that the impact of communication on organiza-

comes may consist of two steps, first a qualitative and tional performance variables can be assessed as a direct path (Kapp

then a quantitative step (John, Ruekert, and Churchill and Barnett 1983; Snyder and Morris 1984).

1983; Robicheaux and El Ansary 1976-1977; Ruekert 3In researching communication, an attempt can be made to measure

facets "objectively" through observation or counting the frequency

with which messages or particular types of messages are sent. Alter-

natively, perceptual data could be gathered from participants of com-

munication. The perceptual approach is adopted here; because com-

munication is a social process, perceptions of interaction typically

'The term "channel conditions" in this article refers to both struc- determine behavior (e.g., Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz 1987; Roberts

tural conditions and behavioral conditions.

and O'Reilly 1974).

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels / 37

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

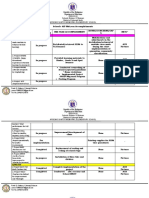

FIGURE 1

Model of Communication for Marketing Channels

EXTANT

CHANNEL CONDITIONS

- Structure

- Climate

- Power

QUALITATIVE QUANTITATIVE

CHANNEL OUTCOMES CHANNEL OUTCOMES

40 - Coordination -p - Performance

- Satisfaction

- Commitment

.

COMMUNICATION

STRATEGYa

- Frequency

- Direction

- Modality

- Content

'A communication strategy is the use of a combination of communication facets (frequency, direction, modality, and co

example, one communication strategy might be frequent bidirectional communication through informal modes, with in

tent.

been studied as both a dependent (cf. Tjosvold 1985) in which written rules and regulations are communi-

and an independent (cf. Kapp and Barnett 1983; Snyder cated downward.

and Morris 1984) variable (O'Reilly, Chatman, and Thus, both communications theory and organiza-

Anderson 1987). Many researchers avoid making di- tional theory suggest a focus on various facets of com-

rect causal statements about the effects of communi- munication, including frequency, direction, modality,

cation and the effects on communication (and they and content (Farace, Monge, and Russell 1977;

conduct simple correlational analyses to avoid the im- Guetzkow 1965; Jablin et al. 1987; Rogers and

plicit treatment of variables as dependent or indepen- Agarwala-Rogers 1976). Furthermore, these four fac-

dent); however, Porter and Roberts (1976, p. 1570) ets have been studied extensively by empirical re-

state that the treatment of communication as a depen- searchers in organizational communication. We ex-

dent variable is supported by the notion that "the total

plore each of these facets in more detail, briefly

configuration of the organization undoubtedly exerts summarizing pertinent findings from both channels and

a strong influence on the characteristics of commu- organizational communication research.4

nication within it."

Communications theory focuses explicitly on Frequency

communication and which facets are appropriately The amount of communication refers to the frequency

studied, but organizational theory does not. Rather, it and/or duration of contact between organizational

generally addresses the nature of organizations and their

role in society (Euske and Roberts 1987). Despite this

lack of specific attention to communication by orga- 4Though the organizational communication literature describes in-

nizational theorists, a close examination of orga- traorganizational communication, communication between channel

nizational theory uncovers implications for com- members is interorganizational. Phillips (1960) suggests that sets of

firms collectively constitute one large organization, which he termed

munication research. For example, the classical an "inter-firm organization:" "firms . . that are members of a group

organizational theorist Max Weber suggested that the which has an identity apart from the individuals of which it is com-

prised" (p. 604). To the extent that channels of distribution constitute

ideal authority structure or bureaucracy has, among an interfirm organization, the organizational communication literature

other characteristics, formal lines of communication is transferable to a channels context, albeit with caution.

38 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

members (Farace, Monge, and Russell 1977). Though mit "rich" information, or a variety of cues including

a minimal amount of contact is necessary to ensure feedback, facial cues, language variety, and person-

adequate coordination, too much contact can overload alization (Lengel and Daft 1985). "Each medium is

organizational members and have dysfunctional con- not just an information source, but is also a complex

sequences (Guetzkow 1965). Therefore, in assessing information-conveying channel" (Huber and Daft 1987,

the frequency of communication, one should examine p. 153). Thus, the authors cited posit a hierarchy of

the amount of contact in relation to the amount of con- media richness, with face-to-face being the most rich,

tact necessary to conduct activities adequately. Be- followed by video-phone, video-conference, tele-

cause most empirical research in organizational com- phone, electronic mail, personally addressed docu-

munication has used frequency as the indicator of the ments (i.e., memos and letters), and, finally, formal

amount of communication, we use the frequency of unaddressed documents.

communication rather than the duration of contact. Other researchers have distinguished modality in

a four-way (2 by 2) classification of commercial/non-

Direction

commercial and personal/impersonal modes (Moriarty

Direction refers to the vertical and horizontal move- and Spekman 1984).5 Commercial modes are con-

ment of communication within the organizational hi- trolled by the party, such as the manufacturer, who

erarchy (Farace, Monge, and Russell 1977). When di- has an advocacy interest in the message. Such modes

rectional flows of communication are studied in an include advertising, sales calls, and trade shows, among

others. Noncommercial modes are those in which in-

intraorganizational context, the typical focus is on su-

perior-subordinate interaction patterns (Dansereau andformation is controlled by a third party other than those

Markham 1987). Such relationships involve clear lines with an advocacy interest (trade journal articles, trade

of authority and status. Because of the clear power ofassociation reports, and consultants). The personal/

the superior over the subordinate, the literature dis-impersonal distinction corresponds to one-on-one

cusses "downward" communication as flowing fromcontact versus mass communication.

the more powerful member to the weaker member. A final way to categorize modality has been to use

In an interorganizational context, the focus is ona formal/informal dichotomy. Though researchers

patterns of contact between organizations. The orga- sometimes fail to define explicitly what is meant by

nizational structure in a channel specifies roles and

formal versus informal modes, Stohl and Redding

tasks of channel members, but authority and status may(1987) clarified a plethora of distinctions. A general

be less clear. Depending on the situation, the manu-difference is that formal modes are those somehow

facturer (the upstream channel member) or the reseller

connected with the organization in a structured, rou-

(the downstream channel member) may be more pow- tinized manner. Formal communication generally re-

erful. Hence, a strict analogy to the intraorganiza- fers to communication that flows through written

tional setting, where communication from the pow- modes, though "formal" meetings (Ruekert and Walker

erful member flows "downward," would hold only if 1987) also may be considered a formal mode. Infor-

the manufacturer is more powerful; if the reseller malis modes are more personalized, such as word-of-

more powerful, communication from the more pow- mouth contacts, which may be spontaneous and can

erful member would be "upward." occur outside the organizational chart or premises.

To account for these two possibilities, our discus- We define modality according to the formal/in-

sions involving communication direction are phrased formal distinction because it has been widely used in

in terms of "unidirectionality" (upward or downward, empirical and conceptual research. Formal modes are

depending on the specific channel context) and "bi-those perceived by organizational members as regu-

directionality" (both upward and downward). Nota- larized and structured; informal modes are those per-

bly, however, the literature from which the discussion

ceived as more spontaneous and nonregularized.

is drawn represents the more powerful party as being

Content

higher in the organizational hierarchy than the less

powerful party. Content of communication refers to the message that

is transmitted-or what is said. Communication in-

Modality

teractions can be analyzed for content by using pre-

The medium of communication, or its modality, re-determined categories (cf. Anglemar and Stern 1978)

fers to the method used to transmit information. Mo- or by asking the parties in an interaction what their

dality has been operationalized in a variety of ways

(Stohl and Redding 1987). One straightforward way

has been to categorize modality as face-to-face, writ-

ten, telephone, or other modes. A second way has been5This categorization corresponds to the direct/indirect dichotomy

of Gross (1968). Direct modes correspond to commercial modes and

to categorize according to the mode's ability to trans-

indirect modes correspond to noncommercial modes.

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels / 39

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

perceptions of the nature of the content are (cf. Frazier compliance with information exchange or requests, for

and Summers 1984). Like modality, content can be example, occur without the source providing addi-

categorized in a variety of ways. Two common cat- tional reinforcement. To extend the empirical work by

egorizations are based on the type of information ex- Frazier and Summers (1984), we categorize content

changed and the type of influence strategy embedded according to their direct/indirect scheme.

in the exchanged information. Gross (1968) examined

five different types of marketing information ex- Channel Conditions and

changed between parties: physical inventory, promo-

Communication Facets

tional activities, product characteristics, pricing struc-

tures, and market conditions. He examined these five

The contingent thesis we propose is that the individua

content areas in isolation from other channel issues

communication facets, as well as aggregate commu-

(such as conflict, coordination, or performance). Re-

nication strategies, moderate the relationship between

search in channel communication that has looked be- channel conditions and outcomes. We use both the

congruence and the consonance approaches to contin-

yond the content of information exchanged to the type

of influence strategy embedded in the communication

gency analysis. Initially we follow the congruence ap-

messages has focused primarily on the content of proach

in- (Mahajan and Churchill 1988), in which the

fluence strategies (Anglemar and Ster 1978; Frazier

relationship between two factors (i.e., between a

and Sheth 1985; Frazier and Summers 1984). channel condition and a facet of communication) is

Frazier and Summers (1984) distinguished be- described. As used here, the congruence approach de-

tween direct and indirect influence strategies. Direct scribes the relationship between each channel condi-

communication strategies are designed to change be- tion (channel structure, channel climate, and power

haviors of the target by implying or requesting the symmetry) and each communication facet. The un-

specific action that the source wants the target to take.derlying, albeit implicit, assumption of the congru-

Examples of direct communication content include re- ence approach is that when the two factors "match,"

quests, recommendations, promises, and appealsoutcome to levels will be enhanced or made greater than

legal obligations. Indirect communication is designed when the two factors do not match. (The consonance

to change the target's beliefs and attitudes about the approach to contingency analysis is discussed subse-

desirability of the intended behavior; no specific ac- quently in the section on Channel Outcomes.)

tion is requested directly. An example of indirect

Channel Structure

communication content is information exchange,

whereby the source uses discussions on general busi- One way to view channel structure is in terms of how

ness issues and operating procedures to alter the tar- exchanges between parties are patterned (Stem and El-

get's attitude about desirable behaviors. Ansary 1988, ch. 7). Channel structures can be dis-

In their study of the usage frequency of particular tinguished by the nature of the exchange relationship

influence strategies, Frazier and Summers (1984) found between parties-relational or discrete. Relational ex-

that the strategies of information exchange and re- changes involve joint planning between parties; the

quests (indirect and direct, respectively) were used most

relationship has a long-term orientation and interde-

frequently within a channel of car dealers, followed pendence is high. Discrete exchanges, in contrast, oc-

by recommendations, promises, threats, and legalistic cur on an ad hoc basis-the relationship between par-

pleas. Information exchange and requests were inter- ties has a short-term orientation and interdependence

correlated positively and their use was correlated neg- is low (Macneil 1981).

atively with promises, threats, and legalistic pleas. Truly discrete exchanges are unlikely in a chan-

Frazier and Sheth (1985) added a finer distinction nels setting, but if the distinction between relational

to the categorization and provide a conceptual, nor- and discrete exchange is viewed as a continuum, some

mative framework on appropriate strategies to use, channel relationships are more relational than others.

depending on the prior attitude of the target toward We use the term "market structure" to describe chan-

the desired behavior. Their categorization is based nel on relationships toward the discrete end of the con-

whether the consequences of accepting or rejecting the tinuum and the term "relational structure" to describe

influence attempt are mediated or unmediated by the channel relationships toward the relational end of the

source. Strategies mediated by the source are thosecontinuum.

in

which the source, contingent upon compliance or non- Following the congruence approach of contin-

compliance, gives either positive or negative rein- gency theory, we posit that communication in rela-

forcement (such as reward or punishment) to the tar- tional channel structures differs from communication

get. Unmediated strategies are those in which the source

in market channel structures. More specifically, com-

does not intervene between the target's action and the

munication in a relational channel structure has higher

outcome. Thus, consequences of compliance or non- frequency and more bidirectional flows, informal

40 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

modes, and indirect content. Conversely, communi- uncertainty prevails, more informal communication

cation in market channel structures has lower fre- contacts may occur. Williamson (1981) says that where

quency and more unidirectional flows, formal modes,uncertainty prevails and transaction costs are present,

and direct content. Support for these ideas is devel- the appropriate structure is relational. Thus, as struc-

oped in the following paragraphs. tures are more relational, communication modes may

Because channel members under relational chan- be more informal. In contrast, in market structures,

nel structures share activities that are more interde- parties may have no opportunity to interact on an in-

pendent than those under market channel structures formal basis and, as a result, communication between

(Macneil 1981), a higher level of communication fre- manufacturer and reseller may flow through more for-

quency may be necessary. Channel members interact mal modes.

more under these conditions because they need to share Relational structures also use different communi-

more information in order to coordinate more closely cation content than market structures. Parties in these

shared activities. Huber and Daft (1987) provide sup- longer term relationships are more willing to share

port for the relationship between higher frequency ofbenefits and burdens (Macneil 1981). Hence influence

communication and relational structures; (for highstrategies are more indirect than direct. Merely pro-

performing units) the greater the interdependence, theviding information to other channel members may be

greater the frequency of communication. Presumably sufficient to encourage them to participate in pro-

task interdependence causes messages to be more rel- grams. Stohl and Redding (1987) also suggest that

evant and thus communication more frequent (Huber mutual dependence reduces the use of tough, distrib-

and Daft 1987). Moreover, for better coordination of utive bargaining tactics.

activities, communication will flow both upward and Furthermore, communication in relational struc-

downward in relational channel structures. Dwyer,tures is likely to reflect relationship maintenance con-

Schurr, and Oh (1987, p. 17) suggest that "a rela- tent (i.e., content aimed at furthering a supportive cli-

tionship seems unlikely to form without bilateral com- mate) as well as instrumental content (e.g., content

munication of wants, issues, inputs, and priorities." aimed at consumating a transaction). Because direct

In contrast, under market channel structures chan- communication strategies are associated more strongly

nel members act more autonomously. Though they arewith conflict (Frazier and Summers 1984), their use

still interdependent in the sense that they share the directly counters the goal of relationship maintenance.

task of moving products from manufacturer to the Therefore, indirect influence strategies are more likely

consumer, members of market channels are com- to be used when channel members attempt to nurture

monly more independent than those in relational chan- a supportive trading atmosphere.

nel structures. Because of the autonomy in decision Market channel structures, in contrast, tend to use

making and their independent nature, communication direct rather than indirect content (Frazier and Summers

frequency is lower in these market channels and 1984).

is Such a strategy may be used in these channel

likely to be primarily unidirectional. Etgar (1976) structures because direct content takes less time and

suggests that conventional or market channel mem- effort to implement; when the link between members

bers contact each other only for specific transactions

is perceived to be short-term, the more expeditious

and usually drift away after the termination of eachstrategy may be preferred.

transaction. Moreover, in conventional channels, The preceding congruence predictions about the

members may reject common communicative proce- relationship between channel structure and the facets

dures as infringements on their independence. of communication are summarized in Table 1 and stated

Channel structure is related to the modality of

formally in the first proposition.

communication in that channels with relational struc-

P1: Under relational channel structures (in comparison with

tures tend to rely on informal modes, whereas those market channel structures), communication has:

with market structures tend to use more formal modes. a. higher frequency,

Again, because the parties in a relational structure are b. more bidirectional flows,

c. more informal modes, and

more intimately linked, communication between the d. more indirect content.

manufacturer and the reseller is commonly more in-

formal. This is not to say that formal communication Channel Climate

modes are not used. The point is that the tighter link-

Organizational climate has been defined in a variety

ages between members allow for more informal in-of ways, depending on the perspective of the re-

teractions.

searcher (Falcione, Sussman, and Herden 1987 offer

Support for more informal modes of communi- further reading in this area). Climate sometimes is

cation under relational channel structures is found in viewed as being similar to culture. In fact, Smircich

the environmental uncertainty and transaction cost lit- and Calas (1987) suggest that culture is simply cli-

eratures. According to Huber and Daft (1987), when mate reborn.

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels /41

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE 1

Relationships Between Channel Conditions and the Facets of Communication

Communication Facets

Conditions Frequency Direction Content Modality

Structure

Relational Higher More bidirectional More indirect More informal

Market Lower More unidirectional More direct More formal

Climate

Supportive Higher More bidirectional More indirect More informal

Unsupportive Lower More unidirectional More direct More formal

Power

Symmetrical Higher More bidirectional More indirect More informal

Asymmetrical Lower More unidirectional More direct More formal

In general, climate is viewed as a representation

climate domain, depending on the way climate

fined.

of the organizational member's perceptions of the work

environment, including such aspects as characteristics

The four factors most commonly associated

of the organization and the nature of the measures

member'sof perceived organizational climate are

relationships with others (cf. Churchill,initiating

Ford, and structure (leadership), leader conside

Walker 1976). Climate develops characteristics di-

(trust, mutual respect), autonomy, and the rewa

rectly reflecting norms, leadership, and membership

entation of management (i.e., how to motiva

composition and provides a context for interpersonal

ployees) (Schul, Little, and Pride 1985; Stern an

communication (Falcione, Sussman, and Herden

Ansary 1987).

1988).

Climate has important implications for organiza-

Despite the problem in conceptual clarity, the re-

tional behavior (and, by extension, channel member

lationship between climate and structure appears to vary

behavior) because of its ties to motivation and

greatly per-and Kaplan 1984). Wilkins and Ouchi

(Falcione

formance (Wilkins and Ouchi 1983). Climate has

(1983) been

suggest that culture is distinct from hierarchy

explored in marketing in conjunction with (structure)

salespersonin that culture can substitute for market or

motivation (Tyagi 1982), satisfaction (Churchill, Ford,

bureaucracy (relationalism) as a form of economic

and Walker 1976), attractiveness of rewards

control.(Tyagi

Additionally, Muchinsky (1977) argues that

1985), channel member satisfaction (Schul, noLittle,

singularand

relationship occurs between organizational

Pride 1985), and resource allocation (Anderson, Lodish,and climate, and that this relationship

communication

and Weitz 1987). Channels researchers who adopt

remains a unexplored (Falcione and Kaplan

virtually

political economy perspective also have 1984).viewed

Churchill, Ford, and Walker (1976) argue that

"transaction climate" as an important determinant of

climate is conceptually distinct from satisfaction, with

performance (Reve 1982). satisfaction being an evaluative outcome. Finally,

The problems in defining organizational climate

Muchinsky (1977) suggests that trust is the most con-

are exemplified by the statement that "climate is po- of organizational climate.

sistent predictor

tentially inclusive of almost all organizationalTo char-

avoid confounds with other constructs, our def-

acteristics" (Jablin 1980, p. 329). Some of inition ofchar-

the climate centers on the dimension of leader

acteristics that have been studied as part of climate Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz (1987)

consideration.

are leadership style, job variety, job autonomy, or- definition in their research on climate.

used a similar

ganizational identification (Tyagi 1985), psychologi-

They took measures of trust and goal compatibility

cal environment, attitude toward management

and developed a measure of climate that was psy-

(Muchinsky 1977), goal compatibility, domain con-

chometrically distinct from both communication and

sensus, evaluation of accomplishment, power.

norms of is defined here as the feelings of

Climate

exchange (Reve 1982), mutual trust, andchannel

goal members

com- about the level of trust and mutual

patibility (Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz 1987). Char- in the interorganizational relationship

supportiveness

acteristics of climate, such as autonomy and job va-

(Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz 1987).

riety, overlap with other organizational variables,

Again, such

our model predicts that communication will

as structure. Other confounds may arise from lead- on whether the channel climate is high

vary, depending

ership and communication. Falcione, Sussman, andand mutual supportiveness. Specifi-

or low in trust

Herden (1987) report that climate may overlap with

cally, communication with higher frequency and more

other variables that may or may not be unique to the

bidirectional flows, informal modes, and indirect con-

42/ Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tent is used in a channel with a high degree of trust. are productive and pleasurable, such interaction may

In contrast, communication with lower frequency and further foster the supportive atmosphere.

more unidirectional flows, formal modes, and direct To the extent that the climate lacks mutual support

content is used in climates lower in trust and mutual and trust, formal communication channels will be used

supportiveness. Support for these ideas is drawn from (Phillips 1960). When members have little in com-

the culture/climate literature. mon, and perhaps have little trust in each other, cred-

The culture literature suggests that when members ible modes of information that are more noncommer-

experience trust and supportiveness in the organiza- cial and formalized (i.e., nonadvocacy oriented, such

tion, they develop a sense of shared identity with the as articles in the press) may be useful. Informal modes

organization. A feeling of shared identity can serve as of contact with a distant or untrustworthy manufac-

a consensual paradigm that structures information ac- turer may lead to information being discounted.

quisition and decision making for organizational Frazier and Summers (1984) suggest that com-

members (Wilkins and Ouchi 1983). As a feeling of munication content utilizing indirect strategies is most

identification with the channel goals is established, the effective if behavior is related to a common goal. One

length of communication pieces declines (because of can use more informational influence strategies if

a shared foundation of knowledge and similarity of common ground or trust is present. If trust is absent,

language usage), whereas the frequency of commu- informational influence strategies may be viewed sus-

nication may increase (O'Reilly, Chatman, and piciously by the target, who may inaccurately per-

Anderson 1987; Pfeffer 1981a). ceive or distort the message. Therefore, under con-

When channel members have no feeling of shared ditions of distrust, indirect influence strategies may be

identity or the climate is low in trust, they may not unsuccessful and direct strategies are employed.

want or need a high level of communication fre- These congruence predictions about the relation-

quency; hence the level is lower (Lengel and Daft ship between channel climate and the facets of com-

1985). A lower level of communication frequency may munication are summarized in Table 1 and stated for-

suffice to keep them informed of channel happenings mally in the second proposition.

but, without a shared identity, members may have no

P2: In mutually supportive and trusting climates (in com-

desire for more than minimal interactions. Moreover, parison with unsupportive, distrustful climates), com-

Triandis and Albert (1987), in their work on cross- munication has:

cultural perspectives, suggest that the more different a. higher frequency,

two cultures are, the more difficult communication b. more bidirectional flows,

c. more informal modes, and

becomes. Thus, by extension, as values are more dis- d. more indirect content.

parate, communication is less frequent.

The presence of trust in working relationships also

Power

affects the direction of communication (Blair, Roberts,

and McKechnie 1985; Fulk and Mani 1986; Guetzkow Power conditions within the channel can be either

1965; Read 1962; Roberts and O'Reilly 1974), and symmetrical, with power balanced between parties, or

empirical findings support more upward communi- asymmetrical, with a power imbalance (Dwyer and

cation in high trust relationships. This aspect of com- Walker 1981). The model of channel communication

munication is a manifestation of the relationship be- developed here predicts that communication under

tween the parties. Under conditions of trust and support, symmetrical power will have higher frequency and more

organizational members more willingly pass infor- bidirectional flows, informal modes, and indirect con-

mation upward (especially if communication is en- tent. Conversely, for asymmetrical power conditions,

couraged). Thus, the increase in upward communi- communication will have lower frequency, primarily

cation adds to the information flowing downward and unidirectional flows, formal modes, and direct con-

communication is more bidirectional where trust is tent.

present. When trust is low, channel members are more Under conditions of symmetrical power, a high

unwilling to pass information upward. Thus, in low frequency of communication occurs and flow is both

trust climates, communication is primarily unidirec- up and down. As power is dispersed, the volume of

tional.

communication increases (Bacharach and Aiken 1977;

Channel members commonly rely on informal Jablin 1987). Because decentralized communication

modes of communication when they have a feeling of patterns are associated with the ability to cope with

shared identity and high trust. Because of the positive, uncertainty, which in turn is associated with greater

supportive atmosphere between them, channel mem- message generation, symmetrical power conditions are

bers may seek information from one-on-one and group associated with higher frequency of communication

verbal modes (Huber and Daft 1987); by giving mem- (Stohl and Redding 1987). Moreover, because the two

bers the opportunity for informal conversations that

parties have equal footing in the relationship, each will

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels / 43

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

try to stay abreast of the other's actions and send mes- suggests that an equal distribution of power is accom-

sages as they try to implement their respective pro- panied by informal communication networks. Another

grams and policies. reason for the use of informal modes under symmet-

Conversely, under conditions of unbalanced power, rical power conditions is that, because the parties may

communication frequency is low, with primarily uni- be jockeying for position, communication through un-

directional flows. Authority, or the centralization of planned modes may be met with less resistance. If

decision making, serves to economize on the trans- formal modes were used, especially for persuasive

mission and handling of information, and thus com- messages, the recipient may disregard the message as

munication is less frequent (Scott 1981). Dwyer and inappropriate.

Walker (1981) provide evidence that, under condi- Indirect communication content is used under

tions of unequal power, communication frequency de- symmetrical power conditions. Because neither party

clines slightly. Furthermore, Etgar (1976) suggests that has more power than the other, information exchange

centralized decision making, by routinizing the op- allows both parties to make their own decisions. In

erations of the channel, can reduce the number of contrast, when power conditions are asymmetrical, the

communicative messages. (These findings apply to more powerful party can use direct communication

participation in strategic decisions rather than work- content. The more powerful member can indicate spe-

related decisions.) Additionally, when contact occurs cifically what actions the less powerful party should

between individuals at different hierarchical levels adopt. Jablin (1987) also suggests that centralization

(asymmetrical power), communication takes place moreleads to open persuasion.

easily from the superior to the subordinate than vice These congruence predictions about the relation-

versa (Guetzkow 1965; Hage, Aiken, and Marrett ship between channel power and the facets of com-

1971). munication are summarized in Table 1 and stated for-

When the parties are unequal in power, frequent mally in the third proposition.

communication may only create tensions and may cause

the less powerful member to perceive the more pow- P3: Under symmetrical power conditions (in comparison

with asymmetrical power conditions), communication

erful party as overbearing. The less powerful member has:

may feel no need to send communication to the other;

a. higher frequency,

the more powerful member may ignore messages and b. more bidirectional flows,

merely dictate his or her own ideas. The less powerful c. more informal modes, and

member may even actively withhold information as a d. more indirect content.

way to gain countervailing power. Blair, Roberts, and

McKechnie (1985) summarize research showing that

the effect of power is to restrict communication flow- Communication Strategies

ing from the less powerful member to the more pow-

erful member. Additionally, less need for feedback The facets of communication are combined to form

arises when power is concentrated, because the role communication strategies. We use the term "com-

of the subordinate (less powerful member) is to im- munication strategy" to refer to a particular combi-

plement decisions rather than to participate in shapingnation of the facets of communication. For example,

decisions (Jablin 1987). a possible communication strategy might consist of a

Phillips (1960) suggests that informal modes ofhigher frequency of communication, with more bidi-

communication are used under conditions of asym- rectional flows, informal modes, and indirect content.

metrical power because the powerful member can nearly Table 1 shows that two specific combinations of

always engender compliance with his or her requests;communication facets emerge. The first combination

however, we suggest that formal modes would be usedincludes higher frequency and more bidirectional flows,

under conditions of asymmetrical power. The reason informal modes, and indirect content. This combi-

for this proposition is that, if power conditions are nation is likely to occur in channel conditions of re-

unbalanced, modes that serve to institutionalize and lational structures, supportive climates, or symmetri-

legitimate the power of the more powerful member cal power. Use of this combination of communication

would be preferred (Pfeffer 1981b); such modes are elements is called "collaborative communication strat-

likely to be formal in the sense that they are structured egy." The second combination of communication ele-

(Salancik and Pfeffer 1977). Moreover, the use of for- ments includes lower frequency and more unidirec-

mal modes to convey messages, especially persuasive tional communication, formal modes, and direct

messages, may cause the less powerful member to view content. This combination is likely to appear with

them as legitimate, acceptable requests. channel conditions of market structures, unsupportive

Under symmetrical power conditions, informal climates, or asymmetrical power. Its use is labeled

modes are used. The work of Burns and Stalker (1961) "autonomous communication strategy."

44 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Channel Outcomes However, Figure 1 shows that communication

strategy may moderate these relationships between

channel conditions and outcomes. Relationships in

One of the critical aspects of the congruence approach

(Mahajan and Churchill 1988) is that it operates which

on a channel condition is associated with enhanced

the untested assumption that when communication "fits"

outcome levels may be found only in situations in which

the channel conditions, outcomes will be enhanced. communication strategy "matches" channel condi-

Thus, the contribution of the second approach to con- tions.

tingency analysis, the consonance approach, is that it Figure 2 illustrates the notion that channels with

explicitly considers how the "fit" between channel enhanced outcomes are ones in which the communi-

conditions and communication affects channel out- cation strategy matches or fits the extant channel con-

comes. In the consonance approach the assumption is ditions (shaded areas), whereas those without en-

that communication strategy "interacts" with a given hanced outcomes are ones in which the communication

channel condition (i.e., channel structure) to deter- strategy mismatches those same channel conditions

mine levels of outcome variables (i.e., channel out- (unshaded areas). "Fit" is determined by the theoret-

comes). Phrased differently, enhanced outcome levels ical development of PI through P3, and thus is present

are contingent on the match of communication strat- when (1) collaborative communication strategies are

egy to channel conditions. used with channel conditions of relational governance

The channel outcomes explored here are coordi- structures, supportive climates, or symmetrical power

nation, satisfaction, commitment, and performance. and (2) autonomous communication strategies are used

Coordination refers to the integration of the different with channel conditions of market governance struc-

parts of the organization to accomplish a collective set tures, unsupportive climates, or asymmetrical power.6

of tasks (Van de Ven, Delbecq, and Koenig 1976). Cells A and D are the so-called "match" cells. In

Channel coordination can be viewed as the synchro- cell A, increased needs for communication within the

nization of activities and flows by channel members. channel are met by the collaborative communication

Channel satisfaction refers to either the affective eval- strategy. Because channel members are provided the

uation (Schul, Little, and Pride 1985) or cognitive necessary and expected communication for channel

evaluation (Frazier 1983) of the characteristics of the conditions, as explicated in the preceding discussion

channel relationship (see also Ruekert and Churchill of congruence propositions, members will experience

1984). Commitment is a multidimensional construct enhanced or greater coordination, satisfaction, and

reflected by the belief in and acceptance of the or- commitment levels. As a result of these greater af-

ganization's goals and values, a willingness to exert fective responses, more effort may be expended on

effort on behalf of the organization, and a strong de- behalf of the manufacturer's product and enhanced

sire to maintain membership in the organization (Porter performance outcomes will obtain.

et al. 1974). Channel commitment implies a behav- In cell D, needs for lower frequency of commu-

ioral component that reflects an allegiance to a chan- nication and different types of content are met by the

nel relationship (Ulrich 1989). Channel performance autonomous strategy. Justification for an autonomous

is a multidimensional outcome measure that can be strategy is given throughout the section on congruence

assessed by considering several dimensions including propositions. Additional justification for autonomous

effectiveness, equity, productivity (efficiency), and strategies comes from a consideration of costs and

profitability (Bennett 1988). benefits. Because collaborative communication costs

Current theory suggests that different types of more in terms of time, effort, and money, it may not

channel conditions are associated with different levels be beneficial under conditions of market structures,

of outcomes. In terms of structure, centralized vertical unsupportive climates, or asymmetrical power. A

marketing systems (i.e., relational structures) are as- manufacturer uses autonomous communication under

sociated with greater levels of coordination (Brown such conditions to get the best outcomes possible at

1981) and greater efficiency (i.e., a performance mea- the least cost. In this cell, the autonomous strategy is

sure) (Etgar 1976; Reve and Ster 1986). As to the the best "match" and enhanced outcomes obtain in the

channel condition of climate, more supportive cli-

mates are associated with higher levels of satisfaction

(Schul, Little, and Pride 1985). In terms of power, 6An implicit assumption to this point is that relational structures,

symmetrical power is associated with more favorable supportive climates, and symmetrical power are isomorphic, as are

market structures, unsupportive climates, and asymmetrical power.

attitudes (i.e., greater satisfaction) of the parties in the

However, it is also plausible that these three constructs do not covary

relationship (Dwyer and Walker 1981). Gaski and isomorphically. For example, in relational structures such as suc-

Nevin (1985) found that higher levels of power in cessful franchise systems (e.g., McDonald's), power asymmetry may

prevail. The section Interactions Between Channel Conditions ex-

general are associated with higher satisfaction and

plores combinations such as relational structures and power asym-

performance. metry.

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels / 45

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 2 inventory turnover) for the manufacturer's product.

Proposed Relationships Between Communication Similarly, in cell B, the collaborative communi-

Strategies and Channel Conditions: Implications cation strategy mismatches the needs of the channel

for Outcome Levelsa

conditions. High frequency of communication is un-

necessary under these channel conditions. Also, the

COMMUNICATION

STRATEGY use of informal modes and indirect content is a mis-

match for market structures. The nonenhanced out-

Collaborative Auto

comes in this cell are not due to communication in-

CHANNEL CONDITIONS

adequacies (as in cell C), but to communication

overload and higher expectations from channel mem-

Relational Structures,

Supportive Climates, or bers about the response of other members to com-

Symmetrical Power munication messages. For instance, if channel mem-

bers are burdened with information overload and are

given what they perceive to be vague content (i.e.,

indirect messages), coordination levels will be lower,

Market Structures,

satisfaction will be stifled, and less commitment will

Unsupportive Climates, or occur.

Asymmetrical Power

The two-step process implies that, eventual

levels of qualitative outcomes will have an im

performance outcomes. The excess energy ex

by channel members on communication acti

"The shaded areas represent enhanced outcome levels, orinwhere

essence a misuse of resources.

communication strategies fit channel conditions. The un-

A suggested rank-ordering of the four cells in terms

shaded areas represent nonenhanced outcome levels, or where

of relative levels of channel outcomes is, from highest

communication strategies do not fit channel conditions.

bAutonomous communication strategy: lower frequency, to more

lowest: cell A, cell D, cell B, and cell C. This

unidirectional flows, more formal modality, more direct con-

suggested

tent. Collaborative communication strategy: higher frequency,

rank-ordering of cells A through D is based

more bidirectional flows, more informal modality, moreon two

in- assumptions. First, it is based on the basic

direct content.

premise of contingency analysis that "fit" or "match"

CRecall that the enhanced outcomes may be manifested ini-

tially in enhanced qualitative outcomes, with the impact on results in enhanced outcomes. Hence, matching cells

quantitative outcomes following. A and D are expected to be associated with relatively

higher outcome levels than mismatching cells B and

C. Second, the rank-ordering is based on the assump-

tion that the presence (match) or lack (mismatch) of

sense that they are the best possible outcomes given an appropriate communication strategy has a stronger

the cost/benefit considerations. effect on channel outcome levels under relational

Cells B and C are the so-called "mismatch" cells. channel structures, supportive climates, or symmet-

In cell C, the autonomous communication strategy does rical power than under market structures, unsuppor-

not match the channel conditions. Under relational tive climates, or asymmetrical power. Hence, match-

channel structures, channel members need to interact ing cell A is expected to be associated with relatively

more because of the need to share information and greater outcome levels than matching cell D. Like-

coordinate closely shared activities. The autonomous wise, mismatching cell C is expected to be associated

strategy, which includes lower frequency of com- with relatively lower outcome levels than mismatch-

munication, unidirectional flows, and formal modes, ing cell B. This proposed stronger effect under rela-

is not adequate in meeting the needs of channel mem- tional structuring, for example, is suggested by the

bers in a relational structure. Because of this mis- dramatically higher interaction expectations (fulfilled

match of communication strategy to the conditions, or unfulfilled) that channel members have under re-

the coordination levels, satisfaction levels, and com- lational as opposed to market structures. For example,

mitment levels are lower than in the match condition. unfulfilled interaction expectations are likely to lead

Lower levels of these qualitative outcomes in turn to relatively lower outcome levels under the higher

can lead to lower levels of quantitative outcomes. As expectations inherent in a relational channel structure.

channel activities are uncoordinated, members are P4 through P6 summarize more specifically the

dissatisfied, and commitment levels decline, less ef- consonance ideas developed in this section.

fort may be expended on behalf of the manufacturer's

P4: Communication strategy and channel structure interact

product. Efforts are uncoordinated, resulting eventu- to influence the level of channel outcomes.

ally in decreased performance (i.e., sales volume and a. When relational structures are present, collabo-

46 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

rative communication strategies are associated with in communications and organizational theory. Though

enhanced outcome levels in comparison with au- the two-way interactions8 between channel conditions

tonomous strategies.

are less solidly grounded in theory, they are a vital

b. When market structures are present, collaborative,

area of concern and warrant individual attention.

communication strategies are associated with non-

enhanced outcome levels in comparison with au-

tonomous strategies. Structure/Climate Interactions

P5: Communication strategy and channel climate interact In this two-by-two interaction, four conditions are

to influence the level of channel outcomes.

compared: (1) relational structures and supportive cli-

a. When supportive climates are present, collabora-

tive communication strategies are associated with mates, (2) relational structures and unsupportive cli-

enhanced outcome levels in comparison with au- mates, (3) market structures and supportive climates,

tonomous strategies. and (4) market structures and unsupportive climates.

b. When unsupportive climates are present, collabo- In general, parties are expected to enter into re-

rative communication strategies are associated with

lational exchanges when a basic element of trust

nonenhanced outcome levels in comparison with

autonomous strategies. is present (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Frazier,

P6: Communication strategy and channel power interact to

Spekman, and O'Neal 1988). Because of this notion,

influence the level of channel outcomes. channel structure and climate might be expected to

a. When symmetrical power is present, collaborative interact to produce more exaggerated effects on com-

communication strategies are associated with en- munication under relational structures and supportive

hanced outcome levels in comparison with auton- climates. In other words, when relational structures

omous strategies.

b. When asymmetrical power exists, collaborative and supportive climates are both present, communi-

communication strategies are associated with non- cation is more frequent, bidirectional, informal, and

enhanced outcome levels in comparison with au- indirect. When trust is absent in a relational exchange,

tonomous strategies. however, communication is less frequent and more

unidirectional, formal, and direct.

Interactions Between Channel In market structures, communication is less au-

Conditions tonomous under supportive than under unsupportive

climates. For instance, when market structures have

All prior propositions are based on the assumption of

a supportive climate, communication may have slightly

no interactions between channel conditions. Hence,

higher frequency, slightly more bidirectionality, and

they posit "main effects." Possibly, however, the so on, than when the market structure has an unsup-

channel conditions may interact with each other.portive

The climate. This interaction is shown in Figure

political economy framework proposed by Stern and 3A and expressed in the following proposition:

Reve (1980) provides some justification for examin-

P7: Structure and climate have an interactive effect on

ing potential interactions among channel structure, communication.

power, and sentiments (climate) within a channel set- a. When structures are relational, communication

ting.7 As indicated by Ster and Reve (1980, p. 59): strategy is significantly more collaborative if cli-

mates are supportive rather than unsupportive.

The essence of the political economy framework . . . b. When structures are market, communication strat-

is that economic and sociopolitical forces are not ana-

egy is slightly less autonomous if climates are sup-

lyzed in isolation... it is imperative to examine

the interactions .. portive rather than unsupportive.

Climate/Power Interactions

This possibility of interactions indicates that the chan-

nel conditions may have an interactive effect on com-Several authors have argued that the effects of power

munication strategy. depend on the context in which the power is exer-

The conceptual exploration of the effects of inter-

cised. For instance, Tjosvold (1985) examined the im-

actions among channel conditions on communication pact of low versus high power supervisors within co-

strategies is more speculative than the preceding dis-

operative, individualistic, or competitive settings. His

cussion, in which the propositions are well grounded

findings indicate that the negative effects of exercis-

ing power are mitigated by a cooperative setting. Bon-

oma (1976) argues that ignoring the social episode, or

7These interaction propositions are congruence propositions that de-

scribe the relationships between the two-way interactions and com-

munication strategy. As before, in the development of these propo- 8Speculation is possible on the three-way interaction of structure,

sitions we implicitly assume that outcomes will be enhanced when climate, and power, but until the relationship between each of the

they are followed. The consonance predictions would address the three

im- channel conditions (and the two-way interactions between them)

pact on channel outcomes of the interaction between the two-way andin-

communication is better understood, such speculation lacks

teractions and communication strategy. grounding.

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels /47

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the context of the power system (unilateral/unequal FIGURE 3

power, mixed power/bargaining situations, or bilat- Effect of Interactions Between Channel

eral power/high mutuality settings), has hindered re- Conditions on Communication Strategy

search on power and conflict. He suggests that context

of power must be considered in order to understand

A. Structure/Climate Interaction

its effects.

Communication

Other researchers have shown that upward com-

Strategy

munication in the organization is a function not only

of the influence (i.e., power) of the superior, but also Collaborative Relational

of the trust the subordinate has in the superior

(Athanassiades 1973; Fulk and Mani 1986; Read 1962; Market

Roberts and O'Reilly 1974). Though the general con-

clusion of the authors is that "influence [of the su- Autonomous

perior] does not seem to be as strongly related to

Unsupportive Supportive

[communication] as is trust" (Roberts and O'Reilly

1974, p. 209), the effects of the difference in power

between parties may not be independent of those of B. Power/Climate Interaction

trust (Read 1962; Roberts and O'Reilly 1974). Communication

Thus, in examining the interaction of power and Strategy

climate, we compare four cells: (1) symmetrical power Collaborative Symmetrical

and supportive climates, (2) symmetrical power and

unsupportive climates, (3) asymmetrical power and

Asymmetrical

supportive climates, and (4) asymmetrical power and

unsupportive climates.

Autonomous

From the findings of Bonoma (1976) and Tjosvold

(1985), one would expect communication to be more Unsupportive Supportive

frequent, bidirectional, informal, and indirect when

power is symmetrical and climates are supportive. C. Structure/Power Interaction

However, when power is symmetrical and climates

Communication

are unsupportive, communication would probably not

Strategy

be as collaborative. A supportive climate might mit-

igate the effects of power asymmetry on communi- Collaborative Symmetrical

cation. For instance, under asymmetrical power, com-

munication may be more frequent, bidirectional, and Asymmetrical

so on if climates are supportive rather than unsup-

portive. This interaction is shown in Figure 3B and Autonomous

expressed in the following proposition.

Market Relational

P8: Power and climate have an interactive effect on com-

munication.

a. When power is symmetrical, communication is

slightly more collaborative in supportive climates

than in unsupportive climates.

b. When power is asymmetrical, communicationformal) planning and programming may occur to

strategy is significantly more autonomous in un- overcome opportunistic tendencies and to cope with

supportive climates than in supportive climates. bounded rationality. This interaction suggests that if

power is asymmetrical, communication strategy is

Structure/Power Interactions significantly more autonomous under market struc-

Stern and Reve (1980) suggest that the type of chan- tures than under relational structures. If power is sym-

nel structure may interact with power conditions in the metrical, however, communication strategy is rela-

tively collaborative in both market and relational

channel. The four cells of this interaction are (1) re-

lational structures with symmetrical power, (2) rela- structures. This interaction is shown graphically in

tional structures with asymmetrical power, (3) market Figure 3C and expressed in the following proposition.

structures with symmetrical power, and (4) market P9: Power and structure have an interactive effect on com-

munication.

structures with asymmetrical power.

In channels with market structures and in which a. When power is symmetrical, communication strat-

egy is slightly more collaborative in relational

power is centralized (asymmetrical), centralized (or structures than in market structures.

48 / Journal of Marketing, October 1990

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

b. When power is asymmetrical, communication using communication to increase the level of channel

strategy is significantly more autonomous in mar- outcomes.

ket structures than in relational structures.

Further theoretical work could expand the mo

by adding other channel conditions. For instance

Managerial Implications and structural aspect of channel complexity (the num

Suggestions for Future Research of levels and intermediaries at each level) and th

Our integrative model of channel communication ad- havioral aspects of the bases of power and con

dresses the current gap in theory on channel com- levels could be added to the model. One postula

munication. The model matches communication fac- might be that under conditions of high conflict,

ets to channel conditions and develops the notion of tonomous communication strategies are used. C

communication strategy as a moderator between chan-ditions outside the channel, such as competitio

nel conditions and outcomes. Looking at combina-regulation, may affect the type of communication. O

variables such as the type of product sold (i.e.

tions of communication facets under various channel

dustrial, consumer, or service) may change comm

conditions affords an understanding of the process by

which channel outcomes occur. The link between nication strategies.

channel conditions and channel outcomes is expli- Other communication facets, such as commun

cated more fully by modeling the complex role of style, distortion of communication messag

cation

communication. and asymmetry of information possession, also c

The model of channel communication developed be added to the model. For instance, different com

munication styles may be used under various cha

here can provide useful managerial insight. If we as-

conditions. Also, interactions between the facets of

sume that empirical support for the model can be found,

normative statements can be made about what com- communication could be explored in future research.

The causal link between communication and chan-

munication strategy managers should use to obtain en-

hanced outcomes. Managers also can use the model nel structure, channel behavior, and channel out-

comes could be investigated. The model developed

to understand how communication facets are linked to

here is based on the notion that channel conditions

channel conditions. They can use the model to un-

derstand how to improve channel outcomes. By de- constrain communication strategies. Communication

scribing the impact on outcomes of the match between strategies, over the long run, may influence channel

communication strategies and channel conditions, the conditions. By proactively using communication strat-

model leads to improved managerial decision making. egies to change channel conditions, manufacturers may

Work is necessary in the area of channel com- be able to influence the channel conditions they face.

munication. Empirical testing of the propositions de-A longitudinal analysis of communication may reveal

how communication affects the evolution of channel

veloped here would be an important first step. Testing

the model might lead to normative prescriptions for structure and behavior.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Erin, Leonard Lodish, and Barton Weitz (1987),Bennett, Peter (1988), Dictionary of Marketing Terms. Chi

"Resource Allocation Behavior in Conventional Chan- cago: American Marketing Association.

nels," Journal of Marketing Research, 24 (February),Blair,

85- Rebecca, Karlene Roberts, and Pamela McKechnie

97. (1985), "Vertical and Network Communication in Orga-

Anglemar, Reinhard and Louis W. Stern (1978), "Develop- nizations: The Present and the Future," in Organizational

ment of a Content Analytic System for Analysis of Bar- Communication: Traditional Themes and New Directions,

gaining Communication in Marketing," Journal of Mar- R. McPhee and P. Tompkins, eds. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

keting Research, 15 (February), 93-102. Publications, Inc.

Athanassiades, John (1973), "The Distortion of Upward Com-

Bonoma, Thomas (1976), "Conflict, Cooperation and Trust in

munication in Hierarchical Organizations," Academy of Three Power Systems," Behavioral Science, 21 (Novem-

Management Journal, 16 (June), 207-26. ber), 499-514.

Bacharach, Samuel and Michael Aiken (1977), "Communi- Brown, James (1981), "A Cross-Channel Comparison of Sup-

cation in Administrative Bureaucracies, Academy of Man- plier-Retailer Relations," Journal of Retailing, 57 (Win-

agement Journal, 20 (September), 365-77. ter), 3-18.

Bagozzi, Richard (1980), "Performance and Satisfaction in an Tom and George Stalker (1961), The Management of

Burs,

Industrial Sales Force: An Examination of Their Anteced- Innovation. London: Tavistock Publications.

ents and Simultaneity," Journal of Marketing, 44 (Spring), Churchill, Gilbert A., Jr., Neil M. Ford, and Orville C. Walker

65-77.

Jr. (1976), "Organizational Climate and Job Satisfaction i

Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels / 49

This content downloaded from

146.102.19.20 on Thu, 03 Sep 2020 15:42:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the Salesforce," Journal of Marketing Research, 13 (No- nels: Behavioral Dimensions, Louis W. Stem, ed. New York:

vember), 323-32. Houghton-Mifflin Company.

Cooper, Charles (1988), "What Do Dealers Want?" Computer Gross, Walter (1968), "Profitable Listening for Manufacturers

and Software News, 6 (May 9), 1. and Dealers: How to Use a Communication System," Busi-

Dansereau, Fred and Steven Markham (1987), "Superior-Sub- ness Horizons, 11 (December), 35-44.

ordinate Communication: Multiple Levels of Analysis," in Guetzkow, Harold (1965), "Communications in Organiza-

Handbook of Organizational Communication, F. Jablin et tions," in Handbook of Organizations, J. March, ed. Chi-

al., eds. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 343- cago: Rand McNally and Company, 534-73.

88. Guiltinan, Joseph, Ismail Rejab, and William Rodgers (1980),

Dwyer, Robert, Paul Schurr, and Sejo Oh (1987), "Devel- "Factors Influencing Coordination in a Franchise Chan-

oping Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of Marketing, nel," Journal of Retailing, 56 (Fall), 41-58.

51 (April), 11-27. Hage, Jerald, Michael Aiken, and Cora Marrett (1971), "Or-