Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Infection Associated With Prosthetic Joints

Uploaded by

Reno WaisyahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Infection Associated With Prosthetic Joints

Uploaded by

Reno WaisyahCopyright:

Available Formats

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

clinical practice

Infection Associated with Prosthetic Joints

Jose L. Del Pozo, M.D., Ph.D., and Robin Patel, M.D.

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem.

Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines,

when they exist. The article ends with the authors’ clinical recommendations.

A 62-year-old woman with osteoarthritis presents with a 7-month history of progres-

sively worsening left hip pain radiating to the groin, 8 months after undergoing total

left-hip arthroplasty. The pain has not responded to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory

drugs. Physical examination reveals a sinus tract overlying her left hip. Her leukocyte

count is 8000 per cubic millimeter, and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level is 15.5 mg

per liter. A radiograph shows loosening of the prosthesis at the bone–cement inter-

face. Synovial-fluid aspirate shows 15×103 cells per cubic millimeter (89% neutro-

phils); cultures of an aspirate from the hip grow Staphylococcus epidermidis. How

should her case be managed?

The Cl inic a l Probl em

The numbers of primary total hip and total knee arthroplasties have been increasing From the Division of Clinical Microbiolo-

over the past decade, with nearly 800,000 such procedures performed in the United gy, Department of Laboratory Medicine

and Pathology (R.P.), and the Division of

States in 2006 (Fig. 1A).1 Procedures to replace the shoulder, elbow, wrist, ankle, tem- Infectious Diseases, Department of

poromandibular, metacarpophalangeal, and interphalangeal joints are less commonly Medicine (J.L.D.P., R.P.), Mayo Clinic Col-

performed. lege of Medicine, Rochester, MN. Ad-

dress reprint requests to Dr. Patel at the

Prosthetic joints improve the quality of life, but they may fail, necessitating revi- Division of Clinical Microbiology and the

sion or resection arthroplasty. Causes of failure include aseptic loosening, infection, Division of Infectious Diseases, Mayo

dislocation, and fracture of the prosthesis or bone. Infection, although uncommon, Clinic, 200 First St. SW, Rochester, MN

55905, or at patel.robin@mayo.edu.

is the most serious complication, occurring in 0.8 to 1.9% of knee arthroplasties3-5

and 0.3 to 1.7% of hip arthroplasties.5-7 The frequency of infection is increasing N Engl J Med 2009;361:787-94.

as the number of primary arthroplasties increases (Fig. 1B).2 Patient-related risk Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society.

factors for infection include previous revision arthroplasty or previous infection

associated with a prosthetic joint at the same site, tobacco abuse, obesity, rheuma-

toid arthritis, a neoplasm, immunosuppression, and diabetes mellitus. Surgical risk An audio version

factors include simultaneous bilateral arthroplasty, a long operative time (>2.5 hours), of this article

and allogeneic blood transfusion, and postoperative risk factors include wound- is available at

NEJM.org

healing complications (e.g., superficial infection, hematoma, delayed healing, wound

necrosis, and dehiscence), atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, urinary tract

infection, prolonged hospital stay, and S. aureus bacteremia.3-6,8-11

Staphylococci (S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococcus species) account

for more than half of cases of prosthetic-hip and prosthetic-knee infection12 (Fig. 2).

S. aureus infection is particularly common in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.13

Other bacteria and fungi cause the remainder of cases.14,15 Propionibacterium acnes

is a common cause of infection associated with shoulder arthroplasty.16 Up to 20%

of cases are polymicrobial, most commonly involving methicillin-resistant S. aureus

(MRSA) or anaerobes.17 Approximately 7% of cases are culture-negative, often in the

context of previous antimicrobial therapy.18

n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009 787

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

tation is typically manifested as acute infection

A

in the first 3 months (or, with hematogenous

600,000

seeding of the implant, at any time) after surgery,

No. of Total Arthroplasties Performed

500,000 Total knee whereas infection with less virulent organisms

replacement (e.g., coagulase-negative staphylococci and P. acnes)

400,000 is more often manifested as chronic infection sev-

eral months (or years) postoperatively. The most

300,000 common symptom of infection associated with a

prosthetic joint is pain. In acute infection, local

200,000

Total hip signs and symptoms (e.g., severe pain, swelling,

replacement erythema, and warmth at the infected joint) and

100,000

fever are common. Chronic infection generally has

0

a more subtle presentation, with pain alone, and

it is often accompanied by loosening of the pros-

89

91

93

95

97

99

01

03

05

07

19

19

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

20

thesis at the bone–cement interface and some-

B times by sinus tract formation with discharge.

7000

Infected total knee S t r ategie s a nd E v idence

No. of Prosthetic-Joint Infections

6000

arthroplasty

5000 Diagnostic Approach

It is important to accurately diagnose prosthetic-

4000

joint–associated infection because its management

3000 differs from that of other causes of arthroplasty

failure. Although there is no universally accepted

2000

Infected total hip definition of this type of infection, the criteria

1000 arthroplasty listed in Table 1 have been applied in a number

of studies.9,12,16,18,20,21

0

Establishing the presence of acute infection or,

89

91

93

95

97

99

01

03

05

in the presence of a draining sinus, chronic infec-

19

19

19

19

19

19

20

20

20

tion, is uncomplicated. In these situations, testing

Figure 1. Total Arthroplasties Performed and Prosthetic

Infections, According to Procedure. may be limited to that needed to establish the

AUTHOR: Patel RETAKE

ICMA shows the number of total arthroplasties per-

Panel

1st microbiologic diagnosis. Chronic infection man-

FIGURE: 1 of 3 2nd

REG Ffrom 1990 through 2006. Data are from the

formed 3rd ifested as localized joint pain alone poses more

Centers

Line 4-C

1 Panel B

CASE for Disease Control and Prevention.Revised

diagnostic difficulty, warranting additional test-

shows the ARTIST:

number of

ts prosthetic-joint infectionsSIZE

from ing. The criteria for interpreting laboratory and

H/T H/T

1990Enon from Kurtz et al.2 16p6

through 2004. Data areCombo

imaging findings in patients with a prosthetic

AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE: joint are distinct from those applied in patients

Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset.

The pathogenesis

with ofcheck

Please infection

carefully.associated with a native joint. In addition to establishing the

a prosthetic joint involves interactions among the diagnosis, the identification of the involved organ-

JOB: 36108

implant, the host’s immune system, ISSUE:

and08-20-09

the in- ism or organisms and their antimicrobial suscep-

volved microorganism or microorganisms. Only a tibility (i.e., on the basis of cultures of synovial

small number of microorganisms is needed to fluid, periprosthetic tissue, the implant, or a com-

seed the implant; such organisms adhere to the bination of such cultures) is important in order

implant and form a biofilm in which they are pro- to guide antimicrobial therapy.

tected from conventional antimicrobial agents and

the host immune system.19 Associated micro C-Reactive Protein

organisms are often skin bacteria that are inoculat In the absence of underlying inflammatory con-

ed at joint implantation. In some cases, organisms ditions, CRP measurement is the most useful pre-

seed the implant hematogenously or through com- operative blood test for detecting infection asso-

promised local tissues. ciated with a prosthetic joint. CRP testing has a

Infection with virulent organisms (e.g., S. aureus sensitivity of 73 to 91% and a specificity of 81 to

and gram-negative bacilli) inoculated at implan- 86% for the diagnosis of prosthetic-knee infection

788 n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical pr actice

with the use of a cutoff point of 13.5 mg per liter

or more.22,23 It has a sensitivity of 95% and a spec-

ificity of 62% for the diagnosis of prosthetic-hip Common causes of prosthetic-knee

and prosthetic-hip infection

infection with the use of a cutoff point of more

Gram-positive cocci (approximately 65%)

than 5 mg per liter.24 Although the CRP level and Coagulase-negative staphylococci

erythrocyte sedimentation rate are elevated after Staphylococcus aureus

Streptococcus species

uncomplicated arthroplasty, the CRP level returns Enterococcus species

to the preoperative level within 2 months, whereas Aerobic gram-negative bacilli (approximately 6%)

Enterobacteriaceae

the erythrocyte sedimentation rate may remain Pseudomonas aeruginosa

elevated for several months.25 A normal CRP level Anaerobes (approximately 4%)

Propionibacterium species

generally indicates an absence of infection, al- Peptostreptococcus species

though false negative results may occur in pa- Finegoldia magna

Polymicrobial (approximately 20%)

tients who have been treated with antimicrobial Culture-negative (approximately 7%)

agents or who have infection that is caused by low- Fungi (approximately 1%)

virulence organisms such as P. acnes. Elevations in

the peripheral-blood leukocyte count and levels

of procalcitonin have low sensitivity for detecting Formation of biofilm

Electron micrograph of

infection. S. epidermidis biofilm

Bone tissue

Imaging

Plain radiography has low sensitivity and low spec-

ificity for detecting infection associated with a

prosthetic joint.26 Periprosthetic radiolucency, os-

teolysis, migration, or all of these features may be Bacterial biofilm

present on radiographs in patients with either in-

fection or aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Di- Prosthesis

agnostic studies with the use of computed tomog-

raphy (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Figure 2. Causes of Infection Associated with Prosthetic Joints.

are hampered by artifacts produced by prostheses,

A small number of often otherwise nonvirulent bacteria contaminate the

although implants that are not ferromagnetic (i.e., implant during surgery and persist as a biofilm despite a functional im-

titanium or tantalum) are associated with mini- mune system and antimicrobial treatment. Commonly isolated microorgan-

mal MRI artifacts, and MRI scans of such im- isms are shown. Unusual organisms that can also cause infection include

plants provide good resolution for detecting soft- (but are not limited to) Actinomyces israelii, Aspergillus fumigatus, Histoplas-

tissue abnormalities. Bone scans obtained after ma capsulatum, Sporothrix schenckii, Mycoplasma hominis, Tropheryma

whipplei, and mycobacterium (including tuberculosis), brucella, candida,

the administration of technetium-99m–labeled corynebacterium, granulicatella, and abiotrophia species.

methylene diphosphonate are sensitive for detect-

ing failed implants but nonspecific for detecting

infection, and they may remain abnormal for more or prosthetic-hip infection, on the basis of pooled

than a year after implantation. Some studies sug- data from several studies, but it is not widely

gest that combined bone and gallium-67 scans are available.27 Newer imaging strategies such as scin-

more specific than bone scans alone. However, tigraphy with antigranulocyte monoclonal anti-

labeled-leukocyte imaging (e.g., leukocytes labeled bodies and hybrid imaging (e.g., combined PET

with indium-111) combined with bone marrow and CT) (see Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Appen-

imaging with the use of technetium-99m–labeled dix, available with the full text of this article at

sulfur colloid is more accurate than bone imag- NEJM.org) are under investigation.

ing alone, combined bone and gallium-67 imag-

ing, or labeled-leukocyte and bone imaging when Synovial-Fluid Studies

compared head to head, and it is considered the If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, the most

imaging test of choice when imaging is required.26 useful preoperative diagnostic test is aspiration

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomog- of joint synovial fluid for a total and differential V

Autho

raphy (PET) has a sensitivity of 82% and a speci- cell count and culture. Aspiration should not be Fig #

ficity of 87% for the detection of prosthetic-knee performed through overlying cellulitis. Hip aspi- Title

ME

DE

Artist

n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009 789 Figur

The New England Journal of Medicine Issue

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

crobiologic study at the time of surgery. Antimi-

Table 1. Criteria for the Diagnosis of a Prosthetic-Joint Infection.*

crobial therapy should be discontinued at least

The presence of at least one of the following findings: 2 weeks before surgery, and perioperative anti-

Acute inflammation detected on histopathological examination of peripros- microbial coverage should be deferred until cul-

thetic tissue ture specimens have been collected. Cultures of

Sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis sinus tract exudates should be avoided; these are

Gross purulence in the joint space often positive because of microbial skin coloni-

Isolation of the same microorganism from two or more cultures of joint aspi- zation and correlate poorly with cultures of sur-

rates or intraoperative periprosthetic-tissue specimens, isolation of the gical specimens.

organism in substantial amounts (e.g., ≥20 CFU per 10 ml from the im- If periprosthetic tissue is obtained, collection

plant in a total volume of 400 ml of sonicate fluid), or both

of multiple periprosthetic-tissue specimens for

* Data are from Berbari et al.,9 Trampuz et al.,12 Piper et al.,16 Berbari et al.,18 aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture is impera-

Marculescu et al.,20 and Betsch et al.21 CFU denotes colony-forming units. tive because of the poor sensitivity of a single cul-

ture and to distinguish contaminants from patho-

gens. A study that used mathematical modeling

ration may require imaging guidance. A synovial- to estimate yield based on the number of cultures

fluid leukocyte count of more than 1.7×103 per concluded that to maximize accuracy, five or six

cubic millimeter or a differential count with more specimens should be submitted for culture, and

than 65% neutrophils is consistent with prosthetic- two or three culture-positive samples would be

knee infection.28 A synovial-fluid leukocyte count considered to be diagnostic.37

of more than 4.2×103 per cubic millimeter or more Periprosthetic-tissue cultures may be falsely

than 80% neutrophils is consistent with prosthetic- negative because of previous antimicrobial ther-

hip infection.29 The leukocyte count cutoffs are apy, leaching of antimicrobial agents from anti-

dramatically lower than those used to diagnose microbial-impregnated cement, biofilm growth on

native-joint infection. Synovial-fluid culture has the surface of the prosthesis (but not in the sur-

a sensitivity of 56 to 75% and a specificity of 95 rounding tissue), a low number of organisms in

to 100%,12,22,30 and to achieve optimal sensitivity tissue, an inappropriate culture medium, an in-

and specificity, it should be performed by means adequate culture incubation time, or a prolonged

of inoculation into a blood-culture bottle.31 If an time to transport the specimen to the laboratory.

organism of questionable clinical significance is Because of poor sensitivity, neither intraoperative

isolated, repeat synovial-fluid aspiration for cul- swab cultures38 nor Gram’s staining of the peripros-

ture should be considered. Previous antimicrobial thetic tissue37 is recommended. Fungal cultures,

treatment reduces the sensitivity. mycobacterial cultures, or both may be considered

(e.g., if bacterial cultures are negative in a patient

Histopathological Examination of Periprosthetic with apparent infection), but they are not rou-

Tissue tinely recommended.

In patients in whom the diagnosis of prosthetic- Microorganisms form a biofilm on the prosthe-

joint–associated infection has not been established sis; therefore, if the prosthesis is removed, obtain-

preoperatively, an intraoperative frozen section may ing a sample from its surface is useful for micro-

be obtained to look for evidence of acute inflam- biologic diagnosis.12 The implant is removed and

mation. In studies that used a polymorphonuclear- transported to the laboratory in a sterile jar. After

cell count ranging from more than 5 to 10 or more the addition of Ringer’s solution, the container is

cells per high-power field as a positive test, sen- vortexed and sonicated (frequency, 40 kHz; power

sitivity for infection ranged from 50 to 93% and density, 0.22 W per square centimeter) for 5 min-

specificity ranged from 77 to 100%32-35; the rate utes in a bath sonicator, and the resultant fluid is

of interobserver agreement was 86%.36 cultured. This technique is more sensitive than and

as specific as multiple periprosthetic-tissue cul-

Intraoperative Microbiologic Testing tures for diagnosing infection of a prosthetic hip,

Identification of the pathogen or pathogens is crit- knee, or shoulder, provided that an appropriate

ical for choosing the antimicrobial regimen; if cutoff for significant results is applied (Table

microbiologic testing has not been done preop- 1).12,16 This technique is particularly helpful in

eratively, specimens should be collected for mi- patients who have received previous antimicrobial

790 n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical pr actice

therapy. In a study involving patients receiving

antimicrobial agents within 2 weeks before sur- Is the patient a candidate

gery, the sensitivity of periprosthetic-tissue culture for operation?

was 45%, whereas the sensitivity of sonicate-fluid Yes No

culture was 75% (P<0.001).12 Sonication in bags is

not recommended because of the potential for

Little functional im- Long-term antimicrobial

contamination.39,40 provement anticipated suppression

after implant exchange (palliative approach)

or

Treatment Multiple previous attempts

The goal of treatment is to cure the infection, pre- to cure infection have

failed

vent its recurrence, and ensure a pain-free, func-

tional joint. This goal can best be achieved by a Yes No

multidisciplinary team consisting of an orthope-

dic surgeon, an infectious-disease specialist, and

Implant removal without Joint implanted <3 mo ago

a clinical microbiologist. On the basis of clinical replacement or hematogenous infection

experience, the use of antimicrobial agents alone, Antimicrobial therapy and

Amputation needed Symptoms present <3 wk

without surgical intervention, ultimately fails in in some cases of uncon- and

most cases. Careful surgical débridement is criti- trolled infection No abscess or sinus tract

and

cal. A general approach to surgical management Implant stable

is outlined in Figure 321,38,41; different centers and and

Organisms other than

surgeons may use slightly different strategies. a multidrug-resistant

Chronic infections require resection arthroplasty organism, small-colony

variant of Staphylococcus

either as a one-stage exchange (i.e., removal of the aureus, Enterococcus

infected prosthesis and reimplantation of a new species, quinolone-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

prosthesis during the same surgical procedure) or or a fungus

a two-stage exchange (i.e., removal of the infected

Yes No

prosthesis and administration of systemic anti-

microbial agents with subsequent implantation of

a new prosthesis, usually between 6 weeks and Débridement with retention One- or two-stage exchange

of prosthesis Antimicrobial treatment

3 months after the first stage). Case series have Antimicrobial treatment

suggested improved outcomes with a one-stage

exchange when polymethylmethacrylate impreg-

nated with one or more antimicrobial agents is Figure 3. Algorithm for the Treatment of Infection Associated with a

AUTHOR: Patel RETAKE 1st

Prosthetic Joint.

ICM

used. A spacer impregnated with one or more an- REG F FIGURE: 3 of 3 2nd

3rd

timicrobial agents may be used to maintain the CASE Revised

leg at its correct length and to control infection EMail

ARTIST: ts

Line 4-C SIZE

H/T H/T

during the prosthesis-free interval of a two-stage a small, randomized

Enon trial comparing

Combo different 22p3

exchange. In a randomized trial involving patients antibiotic regimens in patients

AUTHOR,with

PLEASEstaphylococ-

NOTE:

with infection associated with hip arthroplasty, cal infection of Figure

prosthetic

has beenknees

redrawn or

and hips

type hasor os-reset.

been

Please check carefully.

the use of a vancomycin-loaded spacer (as com- teosynthetic implants, salvage of the implant

pared with no spacer) resulted in a lower rate of was successful in all 12 patients treated forISSUE:

JOB: 36108 3 to 08-20 -09

recurrent infection (11% vs. 33%, P = 0.002).42 6 months with rifampin and ciprofloxacin, as

Patients who have had symptoms of infection compared with successful salvage in 7 of 12

for fewer than 3 weeks, who present with infec- patients treated with ciprofloxacin alone for 3 to

tion within 3 months after implantation or who 6 months (P = 0.02).43

have hematogenous infection, and who have a When unacceptable joint function is anticipated

well-fixed, functioning prosthesis, without a sinus after surgery or the infection has been refractory

tract, and with an appropriate microbiologic di- to multiple surgical attempts at cure, resection

agnosis (Fig. 3) may be candidates for débride- arthroplasty with creation of a pseudarthrosis for

ment and retention of the prosthesis.43 The ad- hips (Girdlestone resection) or arthrodesis for

dition of rifampin is recommended in cases of knees may be considered. If the patient is not a

rifampin-susceptible staphylococcal infection. In candidate for surgery, antimicrobial suppression

n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009 791

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

may be attempted; this approach is unlikely to A r e a s of Uncer ta in t y

cure infection, so the use of antimicrobial agents

is often continued indefinitely. Although surgical intervention is generally recom-

A detailed discussion of antimicrobial therapy mended, the optimal surgical strategy in a given

for infection associated with prosthetic joints is patient remains controversial. Likewise, the opti-

beyond the scope of this article. In brief, infor- mal antimicrobial regimen and its duration are

mation about antimicrobial susceptibility should incompletely defined. The optimal care for patients

be used to confirm the activity of any antimicro- who are initially thought to have aseptic failure

bial agent used for therapy. Data from random- but who have intraoperative culture results that

ized trials on the optimal duration of treatment suggest infection is also uncertain; although a

are lacking. In patients undergoing débridement variety of medical treatments have been success-

with retention of the prosthesis, 3-month cours- ful, further studies are needed to identify pa-

es of treatment for infection associated with hip tients who can be treated with oral antimicrobial

prostheses and 6-month courses for infection as- agents alone and those who may not need medi-

sociated with knee prostheses are often used. Oral cal treatment.48

therapy can be used if the agent has good oral Polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assays may

bioavailability (e.g., quinolones, trimethoprim– provide a more rapid diagnosis than culture and

sulfamethoxazole, and tetracyclines). In patients may facilitate diagnosis in patients with culture-

undergoing a two-stage exchange, systemic anti- negative infection (e.g., as a result of antimicro-

microbial therapy is often administered for 4 to bial therapy),49 but their use in diagnosing infec-

6 weeks. Commercially available, preblended, poly tion associated with a prosthetic joint remains

methylmethacrylate impregnated with an antimi- investigational. Some studies show that a broad-

crobial agent is indicated for use in the second spectrum PCR assay (alone or combined with a

stage of a two-stage revision after elimination specific PCR assay for staphylococcus) may be use-

of active infection.44 Although it is not standard ful in establishing the diagnosis,49,50 but other

clinical practice, two studies involving a long pe- studies indicate that it has low specificity for test-

riod between the initial and second stages sug- ing synovial fluid51 and low sensitivity for testing

gest that when a polymethylmethacrylate spacer synovial fluid, tissue, or both52,53 and thus adds

impregnated with one or more antimicrobial little value to cultures.54

agents or impregnated beads are used, the admin-

istration of systemic antimicrobial therapy for Guidel ine s

2 weeks may be sufficient or systemic therapy may

even be unnecessary.45, 46 Guidelines for the management of infection as-

sociated with prosthetic joints are expected from

Prophylaxis the Infectious Diseases Society of America later

In addition to good aseptic technique and proce- this year.

dures in the operating room, the administration

of intravenous antimicrobial agents immediately C onclusions a nd

before surgery minimizes the risk of infection. R ec om mendat ions

Cefazolin at a dose of 1 g (2 g if the patient

weighs ≥80 kg) every 8 hours or cefuroxime at a The woman in the vignette has a sinus tract, which

dose of 1.5 g, followed by 750 mg every 8 hours indicates that she has an infection associated with

is recommended routinely; vancomycin at a dose a prosthetic joint. Although additional testing is

of 15 mg per kilogram every 12 hours (assuming not needed to support the diagnosis, the elevated

normal renal function) is used in patients with a CRP level, the elevated synovial-fluid leukocyte

β-lactam allergy or MRSA colonization. Prophy- count, and the percentage of neutrophils are con-

laxis should begin within 60 minutes before sur- sistent with infection. S. epidermidis is the likely

gical incision (within 120 minutes if vancomycin pathogen. However, since this organism may be a

is used) and should be completed within 24 hours contaminant, additional culture specimens should

after the end of surgery.47 The entire antimicro- be obtained for confirmation: synovial fluid (ob-

bial dose should be infused before inflation of a tained by reaspiration), five or six tissue specimens,

tourniquet.47 or the implant (subjected to vortexing and soni-

792 n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical pr actice

cation, with culture of the sonicate fluid). Given the Dr. Patel reports having an unlicensed U.S. patent pending

for a method and an apparatus for sonication (and forgoing her

presence of the sinus tract in this case and the dura- right to receive royalties in the event that the patent is licensed)

tion of the patient’s symptoms, she is not a candi- and receiving research funding from Pfizer, Cubist, Arobella

date for débridement and retention of the prosthe- Medical, Bard Medical, and SUBC/Zybac. No other potential

conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

sis. Instead, arthroplasty with a two-stage exchange

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the

plus antibiotics (according to the culture results) authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of

administered for 4 weeks would be appropriate. the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and

Supported by grants from the National Center for Research Skin Diseases, the National Center for Research Resources, or

Resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the the NIH.

NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (1 UL1 RR024150), and by a We thank James M. Steckelberg, M.D., for his thoughtful

grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskel- comments on an earlier version of the manuscript and Brian P.

etal and Skin Diseases (R01AR056647). Mullan, M.D., for his assistance with the section on imaging.

References

1. National Hospital Discharge Survey: after primary hip arthroplasty. Clin Or- 23. Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Garbuz DS,

survey results and products. Atlanta: Cen- thop Relat Res 2008;466:153-8. et al. Use of erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ters for Disease Control and Prevention, 12. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, et and C-reactive protein level to diagnose in-

2009. (Accessed July 24, 2009, at http:// al. Sonication of removed hip and knee fection before revision total knee arthro-

www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds/nhds_products. prostheses for diagnosis of infection. plasty: a prospective evaluation. J Bone

htm.) N Engl J Med 2007;357:654-63. Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1409-16.

2. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, 13. Berbari EF, Osmon DR, Duffy MC, et al. 24. Müller M, Morawietz L, Hasart O,

Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip Outcome of prosthetic joint infection in Strube P, Perka C, Tohtz S. Diagnosis of

and knee arthroplasty in the United States. patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the im- periprosthetic infection following total

J Arthroplasty 2008;23:984-91. pact of medical and surgical therapy in 200 hip arthroplasty — evaluation of the di-

3. Jämsen E, Huhtala H, Puolakka T, episodes. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:216-23. agnostic values of pre- and intraoperative

Moilanen T. Risk factors for infection after 14. Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Cockerill parameters and the associated strategy to

knee arthroplasty: a register-based analy- FR III, Osmon DR. Fungi, mycobacteria, preoperatively select patients with a high

sis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am zoonotic and other organisms in pros- probability of joint infection. J Orthop

2009;91:38-47. thetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Surg 2008;3:31.

4. Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peter- Res 2006;451:64-72. 25. Bilgen O, Atici T, Durak K, Karae

son M. Infection in total knee replace- 15. Idem. Unusual aerobic and anaerobic minoğullari O, Bilgen MS. C-reactive pro-

ment: a retrospective review of 6489 total bacteria associated with prosthetic joint tein values and erythrocyte sedimentation

knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; rates after total hip and total knee arthro-

2001;392:15-23. 451:55-63. plasty. J Int Med Res 2001;29:7-12.

5. Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill 16. Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Cofield RH, et 26. Love C, Marwin SE, Palestro CJ. Nu-

JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: al. Microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic clear medicine and the infected joint re-

the incidence, timing, and predisposing shoulder infection by use of implant soni- placement. Semin Nucl Med 2009;39:66-

factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466: cation. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:1878-84. 78.

1710-5. 17. Marculescu CE, Cantey JR. Polymicro- 27. Kwee TC, Kwee RM, Alavi A. FDG-

6. Choong PF, Dowsey MM, Carr D, Daf- bial prosthetic joint infections: risk fac- PET for diagnosing prosthetic joint infec-

fy J, Stanley P. Risk factors associated tors and outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res tion: systematic review and metaanalysis.

with acute hip prosthetic joint infections 2008;466:1397-404. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35:

and outcome of treatment with a ri- 18. Berbari EF, Marculescu C, Sia I, et al. 2122-32.

fampin-based regimen. Acta Orthop 2007; Culture-negative prosthetic joint infec- 28. Trampuz A, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR,

78:755-65. tion. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:1113-9. Mandrekar J, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Syn-

7. Phillips JE, Crane TP, Noy M, Elliott 19. del Pozo JL, Patel R. The challenge of ovial fluid leukocyte count and differen-

TS, Grimer RJ. The incidence of deep treating biofilm-associated bacterial in- tial for diagnosis of prosthetic knee infec-

prosthetic infections in a specialist ortho- fections. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;82: tion. Am J Med 2004;117:556-62.

paedic hospital: a 15-year prospective sur- 204-9. 29. Schinsky MF, Della Valle CJ, Sporer

vey. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:943-8. 20. Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Hanssen SM, Paprosky WG. Perioperative testing

8. Murdoch DR, Roberts SA, Fowler VG AD, et al. Outcome of prosthetic joint in- for joint infection in patients undergoing

Jr, et al. Infection of orthopedic prosthe- fections treated with debridement and revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone

ses after Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. retention of components. Clin Infect Dis Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1869-75.

Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:647-9. 2006;42:471-8. 30. Virolainen P, Lähteenmäki H, Hil-

9. Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, et 21. Betsch BY, Eggli S, Siebenrock KA, tunen A, Sipola E, Meurman O, Nelimark-

al. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infec- Tauber MG, Mühlemann K. Treatment of ka O. The reliability of diagnosis of infec-

tion: case-control study. Clin Infect Dis joint prosthesis infection in accordance tion during revision arthroplasties. Scand

1998;27:1247-54. with current recommendations improves J Surg 2002;91:178-81.

10. Bongartz T, Halligan CS, Osmon DR, outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1221-6. 31. Hughes JG, Vetter EA, Patel R, et al.

et al. Incidence and risk factors of pros- 22. Fink B, Makowiak C, Fuerst M, Berger Culture with BACTEC Peds Plus/F bottle

thetic joint infection after total hip or I, Schäfer P, Frommelt L. The value of syn- compared with conventional methods for

knee replacement in patients with rheu- ovial biopsy, joint aspiration and C-reac- detection of bacteria in synovial fluid.

matoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; tive protein in the diagnosis of late peri- J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:4468-71.

59:1713-20. prosthetic infection of total knee 32. Ko PS, Ip D, Chow KP, Cheung F, Lee

11. Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Obesity is a replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; OB, Lam JJ. The role of intraoperative fro-

major risk factor for prosthetic infection 90:874-8. zen section in decision making in revision

n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009 793

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

clinical pr actice

hip and knee arthroplasties in a local nandez-Roblas R. Evaluation of quantita- 47. Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicro-

community hospital. J Arthroplasty 2005; tive analysis of cultures from sonicated bial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory

20:189-95. retrieved orthopedic implants in diagno- statement from the National Surgical In-

33. Wong YC, Lee QJ, Wai YL, Ng WF. Intra- sis of orthopedic infection. J Clin Micro- fection Prevention Project. Am J Surg

operative frozen section for detecting active biol 2008;46:488-92. 2005;189:395-404.

infection in failed hip and knee arthro- 41. Sendi P, Rohrbach M, Graber P, Frei 48. Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Hanssen

plasties. J Arthroplasty 2005;20:1015-20. R, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W. Staphylococcus AD, Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR. Prosthetic

34. Francés Borrego A, Martinez FM, Ce- aureus small colony variants in prosthetic joint infection diagnosed postoperatively

brian Parra JL, Grañeda DS, Crespo RG, joint infection. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43: by intraoperative culture. Clin Orthop Relat

López-Durán Stern L. Diagnosis of infec- 961-7. Res 2005;439:38-42.

tion in hip and knee revision surgery: in- 42. Cabrita H, Croci A, De Camargo O, De 49. Vandercam B, Jeumont S, Cornu O, et

traoperative frozen section analysis. Int Lima A. Prospective study of the treat- al. Amplification-based DNA analysis in

Orthop 2007;31:33-7. ment of infected hip arthroplasties with the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection.

35. Nuñez LV, Buttaro MA, Morandi A, or without the use of an antibiotic-loaded J Mol Diagn 2008;10:537-43.

Pusso R, Piccaluga F. Frozen sections of spacer. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2007;62:99-108. 50. Gallo J, Kolar M, Dendis M, et al. Cul-

samples taken intraoperatively for diag- 43. Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, ture and PCR analysis of joint fluid in the

nosis of infection in revision hip surgery. Frei R, Ochsner PE, Foreign-Body Infec- diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection.

Acta Orthop 2007;78:226-30. tion (FBI) Study Group. Role of rifampin New Microbiol 2008;31:97-104.

36. Morawietz L, Classen RA, Schröder for treatment of orthopedic implant-related 51. Panousis K, Grigoris P, Butcher I,

JH, et al. Proposal for a histopathological staphylococcal infections: a randomized Rana B, Reilly JH, Hamblen DL. Poor pre-

consensus classification of the peripros- controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279:1537-41. dictive value of broad-range PCR for the

thetic interface membrane. J Clin Pathol 44. Jiranek WA, Hanssen AD, Greenwald detection of arthroplasty infection in 92

2006;59:591-7. AS. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement for in- cases. Acta Orthop 2005;76:341-6.

37. Atkins BL, Athanasou N, Deeks JJ, et fection prophylaxis in total joint replace- 52. De Man FH, Graber P, Lüem M, Zim-

al. Prospective evaluation of criteria for ment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:2487- merli W, Ochsner PE, Sendi P. Broad-range

microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic- 500. PCR in selected episodes of prosthetic

joint infection at revision arthroplasty. 45. Whittaker JP, Warren RE, Jones RS, joint infection. Infection 2009;37:292-4.

J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:2932-9. Gregson PA. Is prolonged systemic antibi- 53. Fihman V, Hannouche D, Bousson V,

38. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. otic treatment essential in two-stage revi- et al. Improved diagnosis specificity in

Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med sion hip replacement for chronic Gram- bone and joint infections using molecular

2004;351:1645-54. positive infection? J Bone Joint Surg Br techniques. J Infect 2007;55:510-7.

39. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Hanssen AD, et 2009;91:44-51. [Erratum, J Bone Joint Surg 54. Dora C, Altwegg M, Gerber C, Böttger

al. Sonication of explanted prosthetic com- Br 2009;91:700.] EC, Zbinden R. Evaluation of conventional

ponents in bags for diagnosis of prosthetic 46. Stockley I, Mockford BJ, Hoad-Red- microbiological procedures and molecular

joint infection is associated with risk of dick A, Norman P. The use of two-stage genetic techniques for diagnosis of infec-

contamination. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44: exchange arthroplasty with depot antibi- tions in patients with implanted orthope-

628-31. otics in the absence of long-term antibi- dic devices. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:824-5.

40. Esteban J, Gomez-Barrena E, Cordero otic therapy in infected total hip replace- Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society.

J, Martín-de-Hijas NZ, Kinnari TJ, Fer- ment. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:145-8.

posting presentations at medical meetings on the internet

Posting an audio recording of an oral presentation at a medical meeting on the

Internet, with selected slides from the presentation, will not be considered prior

publication. This will allow students and physicians who are unable to attend the

meeting to hear the presentation and view the slides. If there are any questions

about this policy, authors should feel free to call the Journal’s Editorial Offices.

794 n engl j med 361;8 nejm.org august 20, 2009

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on August 28, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Periprosthetic Infection: Farry, DRDocument15 pagesPeriprosthetic Infection: Farry, DRFarry DoankNo ratings yet

- SSI PrventionDocument27 pagesSSI PrventionIPC PFKCCNo ratings yet

- TB Meningitis Lancet 2022Document15 pagesTB Meningitis Lancet 2022stephanie bojorquezNo ratings yet

- 2midterm 8 - Diagnostic Virology TRANSDocument2 pages2midterm 8 - Diagnostic Virology TRANSRobee Camille Desabelle-SumatraNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Pathogenesis and Management of Periprosthetic Joint InfectionDocument30 pagesDiscuss The Pathogenesis and Management of Periprosthetic Joint InfectionNURA MUHAMMAD ALIYUNo ratings yet

- 2-Microscopic IdentificationDocument24 pages2-Microscopic IdentificationMunir AhmedNo ratings yet

- Adenoviruses - Medical Microbiology - NCBI Bookshelf PDFDocument9 pagesAdenoviruses - Medical Microbiology - NCBI Bookshelf PDFNino MwansahNo ratings yet

- Virology Techniques: Chapter 5 - Lesson 4Document8 pagesVirology Techniques: Chapter 5 - Lesson 4Ramling PatrakarNo ratings yet

- Bacteria: Acid Fast Bacilli: Nama Karakteristi K Manifestasi Klinis Struktur Antigen + Enzim + Toxin Diagnosis TerapiDocument2 pagesBacteria: Acid Fast Bacilli: Nama Karakteristi K Manifestasi Klinis Struktur Antigen + Enzim + Toxin Diagnosis TerapiAndreas MoekoeNo ratings yet

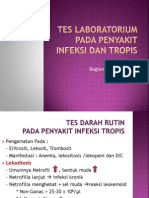

- Tes Lab Penyakit Infeksi Dan Tropis (April 2011)Document143 pagesTes Lab Penyakit Infeksi Dan Tropis (April 2011)Fajrul AnsarNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Jurnal DengueDocument122 pagesKumpulan Jurnal DengueMas MantriNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Meningitis and Brain Abscess: Key PointsDocument7 pagesBacterial Meningitis and Brain Abscess: Key PointsMartha OktaviaNo ratings yet

- I Viral DiseasesDocument41 pagesI Viral DiseasesSagar AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Microbiology '' Microbiology-Clinical Bacteriology Microbiology '' Microbiology-Clinical Bacteriology Section IiDocument8 pagesMicrobiology '' Microbiology-Clinical Bacteriology Microbiology '' Microbiology-Clinical Bacteriology Section IiHanunNo ratings yet

- Gram negative pathogens and the diseases they causeDocument72 pagesGram negative pathogens and the diseases they causelathaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection DR WidDocument36 pagesSurgical Site Infection DR WidNia UswantiNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Foot JAAOSDocument8 pagesDiabetic Foot JAAOSAtikah ZuraNo ratings yet

- Microbiology: Case 1 Bacterial Wound InfectionsDocument11 pagesMicrobiology: Case 1 Bacterial Wound InfectionsNIMMAGADDA, KETHANANo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection GuideDocument41 pagesSurgical Site Infection GuideJawad Mustafa100% (1)

- Musculoskeletal InfectionsDocument12 pagesMusculoskeletal InfectionsSetiawan Suseno100% (1)

- Actinomyces & Nocardia 06-07-MedDocument11 pagesActinomyces & Nocardia 06-07-Medapi-3699361No ratings yet

- DiphteriaDocument64 pagesDiphteriaOmarNo ratings yet

- Actinomycosis: Mohanad N. Saleh 6 Year Meical Student Supervisor: Dr. Anas MuhannaDocument19 pagesActinomycosis: Mohanad N. Saleh 6 Year Meical Student Supervisor: Dr. Anas MuhannaMohanad SalehNo ratings yet

- Lecture 27-Basic Virology-Dr. Ludhang Pradipta Rizki, M.biotech, SP - MK (2018)Document45 pagesLecture 27-Basic Virology-Dr. Ludhang Pradipta Rizki, M.biotech, SP - MK (2018)NOVI UMAMI UMAMINo ratings yet

- Surgical Wound Infection GuideDocument6 pagesSurgical Wound Infection GuideTeddy MuaNo ratings yet

- Fever With Rash SeminarDocument98 pagesFever With Rash SeminarSYAZRIANA SUHAIMINo ratings yet

- Introduction of MGIT Liquid & InstrumentDocument56 pagesIntroduction of MGIT Liquid & InstrumentRosantia SarassariNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster (Shingles) : Muhammad Abdullah Dept. of Dermatology DHQ Hospital FaisalabadDocument26 pagesHerpes Zoster (Shingles) : Muhammad Abdullah Dept. of Dermatology DHQ Hospital FaisalabadwaleedNo ratings yet

- Brucellosis: A Highly Contagious Zoonotic DiseaseDocument55 pagesBrucellosis: A Highly Contagious Zoonotic Diseasesana shakeelNo ratings yet

- Guidelines of Surgical Site InfectionsDocument33 pagesGuidelines of Surgical Site InfectionsAndrie KundrieNo ratings yet

- Pedoman Necrotizing EnterocolitisDocument10 pagesPedoman Necrotizing EnterocolitisMuhamad Zulfatul A'laNo ratings yet

- HO - Dengue VirusDocument2 pagesHO - Dengue VirusSigop Elliot LNo ratings yet

- Influenza: DR.T .V.R Ao MDDocument81 pagesInfluenza: DR.T .V.R Ao MDtummalapalli venkateswara raoNo ratings yet

- Genexpert Ultra JC FinalDocument41 pagesGenexpert Ultra JC FinalmeghaNo ratings yet

- SpirocheteDocument32 pagesSpirocheteSAYMABANUNo ratings yet

- Malaria: Immunology and ImmunizationFrom EverandMalaria: Immunology and ImmunizationJulius P. KreierNo ratings yet

- Spirochetes: Aashutosh Nama M.SC Microbiology Sem - 1 Dr. B Lal Institute of BiotechnologyDocument34 pagesSpirochetes: Aashutosh Nama M.SC Microbiology Sem - 1 Dr. B Lal Institute of Biotechnologyaashutosh namaNo ratings yet

- Immunity To MicrobesDocument25 pagesImmunity To MicrobestimcarasNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis en PDFDocument307 pagesTuberculosis en PDFAbdullah Khairul AfnanNo ratings yet

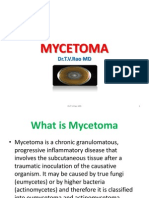

- MycetomaDocument26 pagesMycetomaTummalapalli Venkateswara RaoNo ratings yet

- Scrub TyphusDocument2 pagesScrub TyphusitsankurzNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Coccidian ParasitesDocument23 pagesIntestinal Coccidian ParasitesABC100% (1)

- Meningitis In Children: Signs, Symptoms And TreatmentDocument48 pagesMeningitis In Children: Signs, Symptoms And TreatmentAli FalihNo ratings yet

- Myco - 05 - Dermatophyte & AsperagillusDocument92 pagesMyco - 05 - Dermatophyte & AsperagillusesraaNo ratings yet

- Septic Arthritis & OsteomyelitisDocument42 pagesSeptic Arthritis & OsteomyelitisCabdi WaliNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis BasicsDocument95 pagesTuberculosis Basicstummalapalli venkateswara rao100% (1)

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis - TodarDocument18 pagesMycobacterium Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis - TodarTanti Dewi WulantikaNo ratings yet

- 1 Staphylococcus Lecture 1 Last YearDocument39 pages1 Staphylococcus Lecture 1 Last YearKeshant Samaroo100% (1)

- Infectious Disease Study Guide 2Document32 pagesInfectious Disease Study Guide 2Jim GoetzNo ratings yet

- CMV VirusDocument8 pagesCMV VirusKalpavriksha1974No ratings yet

- Gilut Herpes ZosteRDocument24 pagesGilut Herpes ZosteRdimasahadiantoNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases - Infective EndocarditisDocument41 pagesInfectious Diseases - Infective Endocarditisfire_n_iceNo ratings yet

- Malaria 25 03 09Document131 pagesMalaria 25 03 09Dr.Jagadish Nuchina100% (5)

- Pseudomonas BasicsDocument32 pagesPseudomonas Basicstummalapalli venkateswara raoNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Role of Immunology in SurgeryDocument16 pagesDiscuss The Role of Immunology in SurgeryrosybashNo ratings yet

- Hiv PPDocument37 pagesHiv PPJitendra YadavNo ratings yet

- Tetanu S: By: Reno WaisyahDocument18 pagesTetanu S: By: Reno WaisyahReno WaisyahNo ratings yet

- Histology Saraf2Document1 pageHistology Saraf2reno waisyahNo ratings yet

- Histology Saraf1 PDFDocument1 pageHistology Saraf1 PDFreno waisyahNo ratings yet

- Melamine Contaminated Powdered Formula and Urolithiasis in Young ChildrenDocument8 pagesMelamine Contaminated Powdered Formula and Urolithiasis in Young ChildrenReno WaisyahNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Diarrhea: Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesBacterial Diarrhea: Clinical PracticeReno WaisyahNo ratings yet

- Telenursing: The Future of Transforming CareDocument10 pagesTelenursing: The Future of Transforming CareSujatha J JayabalNo ratings yet

- History Patient - Co.ukDocument14 pagesHistory Patient - Co.ukiuytrerNo ratings yet

- 17 TYPES OF GOOD BACTERIA - The List of Most Beneficial Species of Probiotics Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria - Ecosh LifeDocument30 pages17 TYPES OF GOOD BACTERIA - The List of Most Beneficial Species of Probiotics Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria - Ecosh LifeCarl MacCordNo ratings yet

- Fixed Prosthodontics: Drg. Bertha E. Setio, SpprosDocument16 pagesFixed Prosthodontics: Drg. Bertha E. Setio, Spprosiin revient29No ratings yet

- Research Paper-Hlth1050Document5 pagesResearch Paper-Hlth1050api-691549090No ratings yet

- Emergency Medicine ST3 DRE-EM - 2024 Alternative CertificateDocument8 pagesEmergency Medicine ST3 DRE-EM - 2024 Alternative Certificateiffi82No ratings yet

- Improve Nursing Skills and Knowledge with Medical Case Studies and QuestionsDocument41 pagesImprove Nursing Skills and Knowledge with Medical Case Studies and Questionsjodymahmoud100% (1)

- Asante Teaching Hospital Activity Based CostingDocument3 pagesAsante Teaching Hospital Activity Based CostingMuskanNo ratings yet

- cs3 Protocol-V2.5Document8 pagescs3 Protocol-V2.5CheferishNo ratings yet

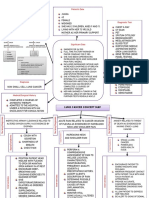

- Lung Cancer Concept Map-Group 2Document2 pagesLung Cancer Concept Map-Group 2Maria Cristina100% (2)

- NCM 107 Postpartum Care Guide QuestionDocument6 pagesNCM 107 Postpartum Care Guide QuestionMiguel LigasNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet TemplateDocument2 pagesPamphlet TemplateZoe ColemanNo ratings yet

- RasproDocument63 pagesRasprofany hertinNo ratings yet

- CRC Model Group-7Document11 pagesCRC Model Group-7Misganaw TadesseNo ratings yet

- PT job descriptionDocument3 pagesPT job descriptionFaer PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Acute & Chronic Rhinitis Types, Symptoms, TreatmentsDocument19 pagesAcute & Chronic Rhinitis Types, Symptoms, TreatmentsAdilah RadziNo ratings yet

- Acute MastitisDocument2 pagesAcute MastitisFatima TsannyNo ratings yet

- Sorbion SachetsDocument3 pagesSorbion SachetsReil_InsulaNo ratings yet

- Rasha Hamdy CVDocument6 pagesRasha Hamdy CVH1552000No ratings yet

- Fluids and Electrolytes in ElderlyDocument7 pagesFluids and Electrolytes in ElderlyDithaNo ratings yet

- Daleel EDocument44 pagesDaleel Ealiplus007No ratings yet

- Ilovepdf MergedDocument53 pagesIlovepdf MergedJoel CalapiñaNo ratings yet

- Type of Hospital AdmissionDocument2 pagesType of Hospital AdmissionPenugasan PerpanjanganNo ratings yet

- Optima Health 2023 2024 Cova - Benefits Brochure FinalDocument8 pagesOptima Health 2023 2024 Cova - Benefits Brochure FinalKobusNo ratings yet

- PelajaranDocument25 pagesPelajaranmarisa isahNo ratings yet

- Test Bank Chapter 5: Patient and Family Teaching: Lewis: Medical-Surgical Nursing, 7 EditionDocument8 pagesTest Bank Chapter 5: Patient and Family Teaching: Lewis: Medical-Surgical Nursing, 7 EditionBriseidaSolisNo ratings yet

- Journal Maria F Delong - Impact of Plaque Burden Vs Stenosis On Ischemic Events in Patient With Coronary AtherosclerosisDocument20 pagesJournal Maria F Delong - Impact of Plaque Burden Vs Stenosis On Ischemic Events in Patient With Coronary AtherosclerosisAris MarutoNo ratings yet

- A Family Physician's Perspective On Vaccine Hesitancy: Margot Savoy, MD, MPH, FaafpDocument6 pagesA Family Physician's Perspective On Vaccine Hesitancy: Margot Savoy, MD, MPH, FaafpNational Press FoundationNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Hepatitis B and CDocument10 pagesLiterature Review On Hepatitis B and Cafmzyywqyfolhp100% (1)

- Clinical Approach in Generalized Pustular Psoriasis One Case Report 63a04e949936aDocument8 pagesClinical Approach in Generalized Pustular Psoriasis One Case Report 63a04e949936aThomas UtomoNo ratings yet