Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Relationship of Atypical Antipsychotics With Development of Diabetes Mellitus

Uploaded by

Leslie CitromeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Relationship of Atypical Antipsychotics With Development of Diabetes Mellitus

Uploaded by

Leslie CitromeCopyright:

Available Formats

Therapeutic Controversies

Relationship of Atypical Antipsychotics with Development of

Diabetes Mellitus

Leslie L Citrome and Ari B Jaffe

OBJECTIVE: To review the pharmacoepidemiologic evidence for the link between exposure to atypical antipsychotics and the

development of diabetes mellitus.

DATA SOURCES: A MEDLINE search (1990–March 2003) was conducted.

STUDY SELECTION AND DATA EXTRACTION: The search was limited to articles that described findings from analyses of large

databases and used the words diabetes or hyperglycemia, and antipsychotic or clozapine or olanzapine or risperidone or quetiapine

or ziprasidone or aripiprazole in the title or abstract. The odds ratio or relative risk, together with their corresponding confidence

interval, was extracted.

DATA SYNTHESIS: Results are conflicting, and this variability may be due to the different populations studied, different study designs,

and the possibility of publication bias related to funding by the pharmaceutical industry. Nevertheless, an increased risk for diabetes

mellitus appears to be present for patients receiving atypical antipsychotics. However, differential risk among the atypical antipsychotics

is difficult to ascertain.

CONCLUSIONS: Clinicians are urged to manage risk by regularly monitoring all patients receiving atypical antipsychotics for the

emergence of diabetes mellitus. Future studies should carefully control for confounding variables such as age, diagnosis, change in

weight, activity level, family history, and ethnicity.

KEY WORDS: clozapine, diabetes mellitus, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone.

Ann Pharmacother 2003;37:1849-57.

Published Online, 5 Nov 2003, www.theannals.com, DOI 10.1345/aph.1D142

everal reports have raised the concern that atypical an- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MedWatch surveil-

S tipsychotic medications may cause or exacerbate prob-

lems with glucose regulation. This has been a major thera-

lance program implicate clozapine, olanzapine, risperi-

done, and quetiapine in new-onset diabetes, including dia-

peutic controversy and was featured recently in the Wall betic ketoacidosis. Reports have pooled FDA data with

Street Journal.1 published cases.3-6 Clozapine had 384 reported cases of di-

Although adverse effects of conventional (typical) an- abetes,3 olanzapine 237,4 risperidone 131,5 and quetiapine

tipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine) on glucose homeostasis 46.6 These cases included instances of diabetic ketoacido-

were known before the introduction of atypical antipsy- sis (80 for clozapine, 80 for olanzapine, 26 for risperidone,

chotics,2 much attention is being placed on this problem 21 for quetiapine), as well as death (25 for clozapine, 15

with the new generation of antipsychotics. Data from the for olanzapine, 4 for risperidone, 11 for quetiapine).

The incidence and prevalence of diabetes among pa-

tients exposed to atypical antipsychotics cannot be calcu-

Author information provided at the end of the text.

lated using the number of case reports alone, but the small

In the past 5 years, Dr Citrome has received honoraria for lectures

or advisory board participation or research support from Abbott

number of cases does provide a signal that merits further

Laboratories, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and attention. Temporal association was observed for some

Pfizer. Dr Jaffe has received research support from Eli Lilly. cases, with 46 patients on clozapine, 60 on olanzapine, and

www.theannals.com The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 ■ 1849

LL Citrome and AB Jaffe

13 on risperidone having improved glycemic control after better able to control for potentially confounding variables,

discontinuation or dose reduction of the drug (these data and, unlike double-blind clinical trials, epidemiologic trials

were not available in the poster abstract for quetiapine). involve much larger numbers of subjects and are thus more

Although this finding suggests that antipsychotic use may likely to be able to detect relatively rare events. Prior re-

unmask or precipitate diabetes in psychotic patients, causali- views have emphasized data from case reports, case series,

ty needs to be ascertained by appropriately designed clini- chart reviews, or naturalistic observations in relatively

cal studies. small samples.14,15 The purpose of this review is to describe

Information from double-blind clinical trials regarding the disparate findings that have emerged from the large

the association of exposure to atypical antipsychotics and database studies published so far and to make research and

diabetes is limited, but consistent with the case reports clinical recommendations.

seen in the literature. In 1 double-blind, randomized, con-

trolled clinical trial comparing clozapine, risperidone, Data Sources

olanzapine, and haloperidol, 14% of 101 subjects devel-

oped hyperglycemia (defined as a fasting plasma glucose A MEDLINE search (1990–March 2003) was conduct-

level >125 mg/dL) within 14 weeks.7 Of these patients, 6 ed regarding pharmacoepidemiologic studies exploring the

had been randomized to receive clozapine, 4 to olanzapine, linkage between exposure to atypical antipsychotics and

3 to risperidone, and 1 to haloperidol. the development of diabetes mellitus. The search was lim-

Determining causality from studies is a difficult chal- ited to articles that described findings from analyses of

lenge, as diabetes has a number of known risk factors such large databases and used the words diabetes or hyper-

as advancing age, weight gain, lack of physical activity, glycemia, and antipsychotic or clozapine or olanzapine or

family history, and ethnicity.8-10 The propensity for atypical risperidone or quetiapine or ziprasidone or aripiprazole in

antipsychotics to cause weight gain is well known, with the title or abstract. Included in this report are all studies

clozapine having the highest risk of weight gain, followed that used large databases to identify cases, the smallest

by olanzapine and quetiapine11; however, not all case re- published study examining 99 cases (from a sample of

ports of type II diabetes associated with atypical antipsy- 3013 pts.)17 and the largest, 7246 cases (from a sample of

chotics were associated with weight gain.3-5 Not all persons 38 632 pts.).18

who have weight gain develop type II diabetes. In addi-

tion, diabetes may also have a long latent period before it Evidence for Atypical Antipsychotic–Associated

is clinically manifested. It is unknown how long exposure Diabetes

to a risk factor is necessary before it has an adverse impact.

This too may vary from patient to patient. Moreover, pa- The database-driven pharmacoepidemiologic studies

tients with schizophrenia may be more likely to develop available thus far provide conflicting evidence for the link-

diabetes mellitus than the general population, and this was age between exposure to atypical antipsychotics and the

observed before the general availability of atypical an- onset or recurrence of diabetes mellitus.17-24 Methodologic

tipsychotic medication.12 The Patient Outcomes Research details of the studies are outlined in Table 1. The studies,

Team Study reported that the percent prevalence of dia- with the exception of one,21 provide information about the

betes mellitus from 1991 through 1996 among patients risk observed with clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, or

with schizophrenia ranged from 11.1% to 14.9% compared quetiapine. A summary of comparative risk of diabetes for

with general population prevalence rates of 1.2% (aged atypical compared with conventional antipsychotics17-20,24

18– 44 y) to 6.3% (aged 45– 64 y). A recent study docu- or risperidone22,23 is presented in Table 2.

mented impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode,

drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia.13 CLOZAPINE

Reviews have discussed possible underlying mecha-

nisms.14,15 Clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are struc- Among the 5 published studies in which information on

turally similar, leading to the idea that they may share sim- clozapine was reported,17-19,22,24 4 implicated clozapine as a

ilar risks. Putative mechanisms include insulin resistance risk factor for diabetes.17,18,22,24 The relative risk (usually de-

caused by antipsychotic agents’ effects on glucose transporters termined using cohort studies) or odds ratios (usually de-

and antagonism of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors decreasing termined using case–control studies) in the reports were as

pancreatic β-cell responsiveness.14 However, regarding the lat- high as 2.5 (95% CI 1.2 to 5.4) among patients aged 20–34

ter mechanism, no significant change in insulin response or years compared with exposure to typical antipsychotics17

insulin sensitivity was detected when a hyperglycemic and 7.44 (95% CI 1.603 to 34.751) at 12 months of treat-

clamp model was used in healthy volunteers randomly as- ment compared with no exposure to antipsychotics.22 A

signed to single-blind therapy treatment with olanzapine, negative report regarding risk with clozapine also exists,

risperidone, or placebo.16 where an almost exclusively older population was exam-

Since 2001, pharmacoepidemiologic studies using pre- ined (mean age of cases 63.6 y, controls 61.9 y).19 This

scription databases have been used to document the associ- negative finding is consistent with another showing that

ation between exposure to antipsychotics and the develop- clozapine was associated with a greater risk of diabetes

ment of diabetes mellitus. Unlike case reports, they are among younger (20–34 y), but not older patients,17 as well

1850 ■ The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 www.theannals.com

Atypical Antipsychotics and the Development of Diabetes Mellitus

as a report of a lack of statistical significance in patients 8.0) compared with nonusers of antipsychotics was shown,

≥70 years old.18 In another study, an elevated risk for pa- but there was no difference when compared with patients

tients taking clozapine (7 cases; HR 3.3; 95% CI 1.4 to taking haloperidol.24

Table 1. Methodology of Pharmacoepidemiology Studies of Atypical Antipsychotics and Risk for Diabetes Mellitus

Total Cases Comparison

Reference Design Pts. (n) Definition of Case (n) AAP Group Comments

Lund et al. retrospective 3013 medical claim for ICD-9 99 CLO TAP users hyperlipidemia and hypertension

(2001)17 cohort; code for diabetes or a were also assessed; small

comparison pharmacy claim for number of cases

of incidence; antidiabetic medication;

IA Medicaid preexisting diabetes excluded

program

Sernyak et al. retrospective 38 632 outpatient encounter or 7246 CLO, TAP users not incident cases

(2002)18 cohort; inpatient stay with either a RIS,

comparison of primary or secondary OLZ,

prevalence; diagnosis of diabetes QUE

VA admini-

strative data-

bases

Wang et al. case–control; 14 007 new prescription for anti- 7227 CLO, AP users mean age of cases and controls

(2002)19 NJ Medicaid, (7227 diabetic medication RIS other than 63.6 and 61.9 y, respectively

Pharmaceutical cases, CLO

Assistance to 6780

the Aged and controls)

Disabled, and

Medicare

programs

Koro et al. case–control; 19 637 diagnosis of or treatment for 451 OLZ, AP nonusers; only 15 cases receiving AAP

(2002)20 UK General (451 diabetes; no prescription of RIS TAP users included in the analysis; CLO

Practice cases, antidiabetic medication within not assessed

Research 2696 3 months of index date

Database controls)

Kornegay et al. case–control; 73 428 new diagnosis of diabetes 424 CLO, AP nonusers same database (but different

(2002)21 UK General (424 without prior evidence of the RIS, years) used as Koro et al.20;

Practice cases, disease or treatment in the OLZ, only 7 pts. received AAP

Research 1522 computer record QUE

Database controls)

Gianfrancesco retrospective 7933 new or resurgent cases of type 101, CLO, AP nonusers; small number of cases; exposure

et al. (2002)22 cohort; 2 diabetes; ICD-CM-9 code 206 RIS, RIS users groups differed in diagnosis;

comparison of for type 2 diabetes or OLZ OR vs. risperidone based on

incidence; prescription for an antidiabetic extrapolated data

database from 2 agent; pts. with type 1

mixed indemni- diabetes (receiving insulin

ty and man- without an accompanying

aged-care type 2 diagnosis) excluded;

health plans pts. with preexisting disease in

past 4–8 mo excluded

Caro et al. retrospective 33 946 ICD-CM-9 code for diabetes 536 RIS, RIS although adjusted for, groups

(2002)23 cohort; or prescription for an anti- OLZ differed significantly in gender,

comparison of diabetic agent; pts. with pre- age, diagnosis, and exposure

incidence; existing disease in past year to haloperidol

database from excluded

the public

health plan in

Quebec

Buse et al. retrospective 58 751a new prescription for anti- 948b CLO, AP nonusers; psychiatric diagnosis not available;

(2003)24 cohort; diabetic medication RIS, TAP users; low doses of AP; risk higher for all

comparison of OLZ, haloperidol AP users compared with non-

incidence; QUE users users, but different pattern seen

AdvancePCS when compared with haloperidol

prescription (Table 2)

claim data

AAP = atypical antipsychotics; AP = antipsychotic; CLO = clozapine; ICD = International Classification of Disease25; OLZ = olanzapine; QUE = que-

tiapine; RIS = risperidone; TAP = typical antipsychotics.

a

5 816 473 in general patient population; 58 751 receiving antipsychotic monotherapy.

b

45 513 in general patient population; 948 receiving antipsychotic monotherapy.

www.theannals.com The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 ■ 1851

LL Citrome and AB Jaffe

RISPERIDONE odds ratios for all atypical antipsychotics studied when ex-

amining patients <40 years of age (2.13 for clozapine, 1.82

Among the 6 published studies that reported specifically

for quetiapine, 1.64 for olanzapine, 1.51 for risperidone).18

on the risks associated with risperidone,18-20,22-24 4 showed

Another study found an elevated risk with olanzapine (HR

no increased risk.19,20,22,23 One trial did show an elevated

3.0; 95% CI 2.6 to 3.5) compared with nonuse of antipsy-

odds ratio for younger patients (<40 y old), but not consis-

chotics, but no difference when compared with haloperidol.24

tently for older patients (statistical significance achieved

In a retrospective cohort study, 319 of 19 153 patients

for ages 50 –59 y, but not for 40 – 49, 60 – 69, or ≥70 y of

age).18 This study was methodologically limited by its ret- developed diabetes while taking olanzapine, and 217 of

rospective cohort design and its use of prevalent, as op- 14 793 developed diabetes while on risperidone.23 There

posed to incident, cases of diabetes mellitus. Another retro- did not appear to be a difference between olanzapine and

spective cohort study, using a large prescription database, risperidone in terms of risk for diabetes using the crude

found an elevated risk for patients using risperidone com- hazard ratio. However, when the relative risk was adjusted

pared with nonusers of antipsychotics (HR 3.4; 95% CI for age, gender, and haloperidol use, a higher risk for olan-

3.1 to 3.8) and haloperidol (HR 1.23; 95% CI 1.01 to zapine was observed that was significant for all patients

1.50).24 and more so for female patients (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.05 to

1.65). Drug exposure time affected the results, with <3

OLANZAPINE

months being statistically significant (RR 1.90; 95% CI

1.40 to 2.57), but not >3 months.

All 5 of the published studies providing specific infor- In a case–control study, 451 cases of diabetes were iden-

mation about olanzapine reported an elevated risk with that tified out of a population of 19 637.20 Although the period

agent.18,20,22-24 Relative risk or odds ratios in those reports from 1987 to 2000 was covered and 3231 patients received

were as high as 4.2 (95% CI 1.5 to 12.2) compared with atypical antipsychotics, only 38 patients who developed di-

exposure to typical antipsychotics,20 and 5.8 (95% CI 2.0 abetes were exposed to atypical antipsychotics. Of these

to 16.7) compared with no exposure to antipsychotics.20 In cases, 9 received olanzapine, 23 received risperidone, and

3 of the studies,20,22,23 olanzapine was associated with a 6 received other atypical antipsychotics. Because the prin-

higher risk of diabetes than was risperidone; however, one cipal analysis used cases involving mutually exclusive sin-

trial reported similar statistically significant magnitudes of gle-agent exposure, only 15 cases were used. Among these

Table 2. Statistical Comparisons of Risk of Diabetes Mellitus by Exposure to Atypical Antipsychotics

Compared with a Reference Antipsychotic

Industry

Reference Statistic CLO RIS OLZ QUE AAP Sponsor

Lund et al. (2001)17 RR vs. TAP 2.5 NA NA NA NA none

(1.2 to 5.4)a

Sernyak et al. (2002)18 OR vs. TAP ↑ risk 1.51 ↑ risk ↑ risk ↑ risk none

(95% CI) (1.12 to 2.04)b

1.25 1.11 1.31 1.09 none

(1.07 to 1.46) (1.04 to 1.18) (1.11 to 1.55) (1.03 to 1.15)

Wang et al. (2002)19 OR vs. AP no increasec no increasec NA NA NA none

other than CLO

Koro et al. (2002)20 OR vs. TAP NA no increasec ↑ risk NA NA Bristol-Myers

(95% CI) 4.2 Squibb (ARI)

(1.5 to 12.2)

Kornegay et al. OR NA NA NA NA NA none

(2002)21

Gianfrancesco et al. extrapolated ↑ risk NA ↑ risk NA NA Janssen (RIS)

(2002)22 OR vs. RIS 8.45 3.53

(p < 0.05) (p < 0.05)

Caro et al. (2002)23 RR vs. RIS NA NA ↑ risk NA NA Janssen (RIS)

(95% CI) 1.20

(1.00 to 1.43)

Buse et al. (2003)24 HR vs. no increasec ↑ risk no increase decreased risk no increase Eli Lilly (OLZ)

haloperidol 1.23 0.67

(95% CI) (1.01 to 1.50) (0.46 to 0.97)

AAP = atypical antipsychotics as a class compared with typical antipsychotics; AP = antipsychotic; ARI = aripiprazole; CLO = clozapine; NA = not

assessed or not applicable; OLZ = olanzapine; QUE = quetiapine; RIS = risperidone; TAP = typical antipsychotic.

a

Increase for patients aged 20–34 years.

b

Increase for patients <40 years old.

c

RR or OR omitted.

1852 ■ The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 www.theannals.com

Atypical Antipsychotics and the Development of Diabetes Mellitus

15 cases, 7 patients received olanzapine, 7 received risperi- 1.11 to 1.62) compared with nonuse of these agents.19 An-

done, and 1 received an unspecified newer agent. Olanza- other trial found a significantly elevated odds ratio for pa-

pine had a significantly increased risk of producing diabetes tients receiving typical antipsychotics (1.3; 95% CI 1.1 to

than nonuse of antipsychotics (OR 5.8; 95% CI 2.0 to 16.7) 1.6) compared with patients not receiving typical antipsy-

and conventional antipsychotics. Although the analogous chotics (includes both nonusers of antipsychotics and users

odds ratios for risperidone were elevated, those results were of atypical antipsychotics).20 An elevated odds ratio was

not statistically significant. Direct comparisons between reported in 1 study for both high-potency (1.065; 95% CI

olanzapine and risperidone were not made. Clozapine was 1.008 to 1.126) and low-potency (1.109; 95% CI 1.036 to

not included in the study design. 1.187) typical antipsychotics compared with nonuse of an-

Another retrospective cohort study eliminated patients tipsychotics.22 Haloperidol use was shown to be a signifi-

whose diabetes had been reported in the prior 4 months.22 cant predictor for users developing diabetes, with a relative

Eighty-three new cases of diabetes were identified among risk of 1.24 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.47) adjusting for age and

patients not receiving antipsychotic treatment (out of 3061 gender when comparing olanzapine and risperidone.23 The

pts.), 25 of 1368 patients receiving risperidone, 32 of 1047 highest risk figures for typical antipsychotics were a haz-

receiving olanzapine, 4 of 64 receiving clozapine, and 62 ard ratio of 3.5 (95% CI 3.1 to 3.9) for conventional an-

of 1856 receiving conventional antipsychotics. Estimated tipsychotics as a group, 3.1 (95% CI 2.6 to 3.7) for

odds ratios that reflect diabetic effects associated with 1 haloperidol, and 4.2 (95% CI 3.2 to 5.5) for thioridazine

month of treatment (compared with no antipsychotic treat- compared with nonuse of antipsychotics.24 There was no

ment) found an elevated odds ratio for olanzapine (1.099; difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics.

95% CI 1.041 to 1.160) and clozapine (1.182; 95% CI

1.040 to 1.344), but not for risperidone (0.989; 95% CI Additional Risk Factors for Antipsychotic-

0.921 to 1.063). These confidence intervals overlap, mak- Related Hyperglycemia

ing direct comparisons difficult. To counter this, the au-

thors extrapolated these figures to 12-month ratios to cal- The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains a

culate the odds ratio versus risperidone treatment and large database of adverse drug reactions from the national

found a statistically significant elevation in risk for olanza- centers in 63 countries around the world. Reports were

pine (OR 3.53), clozapine (OR 8.45), and low-potency identified for clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone in the

conventional antipsychotics (OR 3.93). WHO database that included the following diagnoses: glu-

cose tolerance abnormal, hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus,

QUETIAPINE, ZIPRASIDONE, AND ARIPIPRAZOLE diabetes mellitus aggravated, ketosis, diabetic coma, and

glycosuria.30 The methodology differs significantly from a

As of March 2003, only 2 published pharmacoepidemio- retrospective cohort or case–control study, and is thus not

logic studies have specifically reported on the risk associated included in Table 1. The report does outline risk factors as-

with quetiapine,18,24 and none has reported on the relative risk sociated with hyperglycemia among the antipsychotics.

or odds ratios for exposure to ziprasidone or aripiprazole. There were 868 reports of glucose intolerance with cloza-

Poster presentations have included quetiapine26-28 or ziprasi- pine (n = 480), olanzapine (n = 253), and risperidone (n =

done28; however, these reports were not peer-reviewed and 138). For clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone grouped

may represent only interim analyses. The paucity of peer-re- together, potential risk factors (measured by OR) identified

viewed published studies regarding these newer agents prob- were an underlying diabetic condition (10.22; 95% CI 8.20

ably relates to their more recent commercial availability (que- to 12.73), weight increase (2.36; 95% CI 1.76 to 3.17),

tiapine released in 1997, ziprasidone in 2001, aripiprazole in male gender (1.27; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.47), and use of val-

2002) compared with the other atypical antipsychotics. proate (1.97; 95% CI 1.61 to 2.40), serotonin-specific re-

One trial reported an odds ratio of 1.31 at all ages (95% uptake inhibitors (1.63; 95% CI 1.33 to 1.99), or buspirone

CI 1.11 to 1.55) for quetiapine,18 generating a lively ex- (2.24; 95% CI 1.33 to 3.77).

change of correspondence in a subsequent issue of the

American Journal of Psychiatry.29 Another trial found a Discussion

hazard ratio of 1.7 (95% CI 1.2 to 2.4) for quetiapine com-

pared with nonuse of antipsychotics, but 0.67 compared STUDY VARIATION AND METHODOLOGIC

with haloperidol (95% CI 0.46 to 0.97), signifying de- CONSIDERATIONS

creased risk.24

Direct comparisons of risk between different atypical

CONVENTIONAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS antipsychotics have for the most part failed to yield any

statistically significant differences. However, studies have

Some of the published studies found increased risk asso- rarely had the statistical power to perform such direct com-

ciated with the older medications, although usually not of parisons due the relatively small number of cases of new-

the same magnitude attributable to the atypical agents.21 onset diabetes mellitus. For example, in one case–control

Elevated risks were shown for chlorpromazine (OR 1.31; study, the analysis was limited by the low number of sub-

95% CI 1.09 to 1.56) and perphenazine (OR 1.34; 95% CI jects receiving atypical antipsychotics and developing dia-

www.theannals.com The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 ■ 1853

LL Citrome and AB Jaffe

betes (n = 8).21 Thus, although the odds ratio was elevated tients falling into this group was not reported, but may pro-

for patients receiving atypical antipsychotics and develop- duce bias against olanzapine. Mutually exclusive cate-

ing diabetes compared with those not receiving antipsy- gories were used in another investigation, but that resulted

chotics (OR 4.7; 95% CI 1.5 to 14.9), a direct comparison in the reduction of risperidone-exposed cases from 23 to 7,

between atypical and typical antipsychotics could not be and olanzapine-exposed cases from 9 to 7.20 The unequal

made. That trial21 used the same database (United King- dropping of cases for further analysis makes the results

dom’s General Practice Research Database) as another more difficult to correctly interpret.

study20; however, different calendar years were examined Other key differences that may affect outcome include

(1994 –199821 vs. 1987–200020), which may help explain the definition of diabetes mellitus used (most often the

the differences in the number of cases found and the ability presence of a prescription for an antidiabetic agent and/or

to contrast the atypical antipsychotics. the presence of a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus), time on

Psychiatric diagnosis may impact on diabetes risk and medication, length of observation, and calendar year from

may be a source of bias. Schizophrenia has been associated which the data were extracted. Over time, the diagnostic

with an increased risk of diabetes, regardless of antipsychot- criteria of diabetes may undergo changes. For example, the

ic use.12 As discussed briefly in the introduction, there may 1980–1985 WHO criterion of a fasting blood glucose level

be underlying differences among patients with schizophre- ≥140 mg/dL for the diagnosis of diabetes is substantially

nia in how they maintain glucose homeostasis. In one study, different from the current American Diabetes Association

>15% of the first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizo- definition of ≥126 mg/dL.33 As clinicians become more

phrenia had impaired fasting glucose tolerance compared aware of the problem of diabetes, there may be earlier

with none of the matched healthy comparison subjects.13 identification and increased surveillance, and some clini-

Patients with schizophrenia had higher levels of plasma cians may opt to avoid certain antipsychotics in high-risk

glucose, insulin, and cortisol than the controls. Dysregula- patients. These factors may artificially decrease the ob-

tion of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and im- served risk for the suspected agent and increase the ob-

munologic explanations have been offered.13,31 Thus, dif- served risk for the alternative antipsychotic. The database-

ferential use of antipsychotics based on diagnosis can in- driven studies published so far use data obtained several

crease the observed risk for antipsychotics used in the years ago (from 1990–199417 to 1998–200024).

more vulnerable population. Important missing information common to most of the

In one trial, 57% of the clozapine patients, 22% of the pharmacoepidemiologic studies reported is the lack of data

olanzapine patients, and 14% of the risperidone patients on the extent of laboratory surveillance for the emergence

were diagnosed with schizophrenia.22 Another study in- of diabetes mellitus,17-24 changes in weight or body mass

cluded more olanzapine patients diagnosed with schizophre- index (BMI),17-20,22-24 or ethnicity.17,20-24

nia (62%) than the risperidone group (39%).23 A case–con- An additional source of variation in study results may

trol study included the “presence of schizophrenia or other be sponsor participation, particularly where the studies are

psychotic disorders” in the multivariate logistic regression conducted under the financial aegis of the company and

model, but did not separate schizophrenia.19 Diagnosis of company employees are named authors.20,22-24 This contro-

schizophrenia was included in one model: 12% of cases versy is not new. Others have noted that industry-sponsored

and 10% of controls were diagnosed with schizophrenia.21 reports have usually favored the company’s product.34-39 Al-

No information about diagnosis was included in 1 report,24 though differing results can be attributable to legitimate

and the average daily doses of the atypical antipsychotics methodologic differences, studies countering the compa-

(clozapine 183.1 mg, risperidone 1.2 mg, olanzapine 5.1 ny’s commercial interests would probably not be purpose-

mg, quetiapine 79.9 mg) were substantially less than those ly published. The actual extent of this possible publication

used in seriously and persistently mentally ill patients in bias is unknown. Industry sponsorship of articles is indi-

state hospitals in New York (most with either schizophre- cated in Table 2.

nia or schizoaffective disorder and receiving, on average,

daily doses of clozapine 494.7 mg, risperidone 4.9 mg, Antipsychotic-Related Diabetes Risk in Clinical

olanzapine 18.9 mg, quetiapine 518.4 mg).32 Three trials Context

examined only patients with schizophrenia, thus avoiding

this possible confounding variable.17,18,20 Major unresolved issues relate to the magnitude of the at-

The choice of differing comparison groups (e.g., pts. re- tributable risk of atypical antipsychotics in the genesis of dia-

ceiving typical antipsychotics17-20,23,24 vs. those not receiving betes mellitus and the acceptable degree of this additional

antipsychotics20-22,24) may also affect the results of a study. risk given the efficacy of the antipsychotic medication in

Persons not receiving antipsychotics can represent a sub- question. Family history, advancing age, obesity, and lack of

stantially different mix of diagnoses and illness severity. physical activity are strong risk factors for diabetes mellitus.10

Classification of subjects may introduce bias. One study The relative risks of diabetes attributable to antipsychotic

attempted to directly contrast the risk for olanzapine and medications need to be seen in this context.

risperidone in a cohort of patients who received at least 1 Data from an epidemiologic study of military personnel

prescription for either medication.23 Patients receiving both found that increased BMI was associated with an increased

were assigned to the olanzapine group. The number of pa- risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus as measured by an odds ra-

1854 ■ The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 www.theannals.com

Atypical Antipsychotics and the Development of Diabetes Mellitus

tio of 3.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 6.4) for BMI at least 30 kg/m2, needed to better ascertain the nature of the relationship be-

and 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 3.0) for 25.0 –29.9 kg/m2, com- tween exposure to specific atypical antipsychotic medica-

pared with the risk with a BMI <20 kg/m2.8 A BMI of tion and diabetes mellitus, and to determine what interven-

20.0 –24.9 kg/m2 did not confer a statistically significant ing factors play a major role, including genetic predisposi-

increased risk compared with a BMI <20 kg/m2. Non- tion, psychiatric diagnosis, and severity of illness. In the

white ethnicity resulted in elevated odds ratios of 2.0 (95% meantime, clinicians should allow efficacy considerations

CI 1.6 to 2.6) for African Americans and 1.6 (95% CI 1.1 to drive treatment decisions. Patients who will develop

to 2.4) for Hispanics and others. The military population is clinical difficulties with glucose regulation are not pre-

particularly well suited to the study of risk factors associat- dictable on the basis of antipsychotic choice alone.

ed with diabetes because regular physical examination

records for a large cohort of young individuals are avail- ADDENDUM: In the interval of time between acceptance of

able, and the cases of diabetes are all incident cases (dia- the accompanying article and its publication, there have

betes is cause for rejection into military service). been additional contributions to the pharmacoepidemio-

A recent report also quantified the risk of diabetes asso- logic literature that are of interest. Two of these articles are

ciated with television watching and other sedentary behav- by the same lead author42,43 and are retrospective cohort

iors, where each 2-h/d increment in watching television studies that are methodologically similar to a prior report.22

was associated with a 23% (95% CI 17% to 30%) increase The focus of one article, coauthored by employees of

in obesity and a 14% (95% CI 5% to 23%) increase in the Janssen, was on the differential effects of antipsychotic

risk of diabetes among women.9 With these data as a com- agents on the risk for developing diabetes in patients with

parison, it appears that the increased diabetes risk associat- mood disorders (n = 5723).42 The study concluded that, un-

ed with use of atypical antipsychotic medications is compa- like patients who received risperidone or high-potency

rable to many of the established risk factors for this illness. conventional antipsychotics, patients who received olanza-

However, any increased risk associated with the medica- pine and low-potency conventional antipsychotics had sig-

tions needs to be balanced against the significant morbidity nificantly higher odds for the development of diabetes

and mortality associated with untreated schizophrenia. compared with untreated patients. Extrapolated odds ratios

Schizophrenia has a significantly increased mortality from were 4.289 (95% CI 2.102 to 8.827) for olanzapine and

natural and unnatural causes, with a meta-analysis demon- 4.972 (95% CI 1.967 to 12.612) for low-potency conven-

strating a 12-fold increase in suicide mortality, a 3-fold in- tional antipsychotics. The other report, coauthored by an

crease in accidental death mortality, and a 2.3-fold increase AstraZeneca employee, compared risperidone, olanzapine,

in natural death mortality.40 quetiapine, and conventional antipsychotics across a mix

of diagnoses (n = 16 878).43 Extrapolated odds ratios were

Clinical Recommendations significantly higher for olanzapine (1.426; 95% CI 1.046

to 1.955) compared with no exposure to antipsychotics. An

Given that schizophrenia is a devastating illness, and that

elevation in risk was not observed for risperidone and que-

finding efficacious treatments remains a significant chal-

tiapine.

lenge, the issue of an incremental risk for diabetes should

In a retrospective cohort study conducted in a Veterans

not discourage the clinician from using atypical antipsy-

Affairs Integrated Service Network (n = 5837) and coau-

chotics, provided that the risk is appropriately managed.41

This can be done by regularly monitoring all patients receiv- thored by a Janssen employee, olanzapine was associated

ing any antipsychotic with fasting blood glucose determina- with a significantly higher risk of development of diabetes

tions (baseline, then quarterly or semiannually), especially in compared with risperidone (HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.06 to

the presence of additional risk factors such as obesity, ad- 1.76).44 A number of covariates were used including eth-

vancing age, hypertension, family history of diabetes, and a nicity, age, and diagnosis. Others, such as weight and fami-

low level of physical activity.15 ly history, were not available, a limitation common to the

pharmacoepidemiologic literature on this topic.

In August 2003, at a meeting of the International Soci-

Summary ety for Pharmacoepidemiology and the International Soci-

Given the pattern of results in the database-driven stud- ety of Pharmacovigilance, data were presented that de-

ies, exposure to atypical antipsychotics increases the risk scribed a retrospective cohort study among patients with

for diabetes mellitus. To date, published cohort and case– schizophrenia in the Department of Veterans Affairs (n =

control studies have involved only small numbers of cases 12 235).45 Compared with exposure to conventional an-

(despite relatively large total samples), making assessment tipsychotics, hazard ratios were significantly elevated for

of quantitative differences in relative risk attributable to the olanzapine (1.27; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.56), risperidone (1.49;

different atypical antipsychotics difficult to ascertain. Ab- 95% CI 1.22 to 1.81), and quetiapine (3.34; 95% CI 2.51

solute risk attributable to specific antipsychotic exposure is to 4.45), but not for clozapine (1.48; 95% CI 0.65 to 3.37).

difficult to measure because of the presence of established Data were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and mea-

risk factors. sures of diabetes screening. Although this was not peer-re-

Large-scale, long-term prospective epidemiologic co- viewed the way a journal article would be, it received a

hort studies, as well as randomized clinical trials, will be substantial amount of press coverage.46

www.theannals.com The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 ■ 1855

LL Citrome and AB Jaffe

Whether there is any predictive value in prescribing 1 19. Wang PS, Glynn RJ, Ganz DA, Schneeweiss S, Levin R, Avorn J.

Clozapine use and risk of diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychopharmacol

atypical antipsychotic over another with respect to the risk 2002;22:236-43.

for diabetes mellitus remains unknown. The FDA recently 20. Koro CE, Fedder DO, L’Italien GJ, Weiss S, Magder LS, Kreyenbuhl J,

notified the manufacturers of the atypical antipsychotics et al. Assessment of independent effect of olanzapine and risperidone on

that product labeling for all drugs in that class will require risk of diabetes among patients with schizophrenia: population based

nested case–control study. BMJ 2002;325:243-7.

a new warning about hyperglycemia and diabetes.47 This 21. Kornegay CJ, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick H. Incident diabetes associ-

will ultimately benefit all of our patients, as it will lead to ated with antipsychotic use in the United Kingdom General Practice Re-

improved surveillance for a disease that affects millions of search Database. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:758-62.

22. Gianfrancesco FD, Grogg AL, Mahmoud RA, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA.

US adults.48 Differential effects of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and conven-

tional antipsychotics on type 2 diabetes: findings from a large health plan

Leslie L Citrome MD MPH, Professor of Psychiatry, New York Uni- database. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:920-30.

versity School of Medicine, New York, NY; Director, Clinical Research 23. Caro J, Ward A, Levinton C, Robinson K. The risk of diabetes during

and Evaluation Facility, Nathan S Kline Institute for Psychiatric Re- olanzapine use compared with risperidone use: a retrospective database

search, Orangeburg, NY analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:1135-9.

Ari B Jaffe MD, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, New York Uni- 24. Buse JB, Cavazzoni P, Hornbuckle K, Hutchins D, Breier A, Jovanovic

versity L. A retrospective cohort study of diabetes mellitus and antipsychotic

Reprints: Leslie L Citrome MD MPH, Nathan S Kline Institute for treatment in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:164-70.

Psychiatric Research, 140 Old Orangeburg Rd., Orangeburg, NY 25. International classification of disease. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd9.htm (ac-

10962-2210, FAX 845/398-5483, citrome@nki.rfmh.org cessed 2003 Oct 16).

26. Lambert BL, Chou CH, Chang KY, Carson W, Tafesse E. Antipsychotic

use and new onset type II diabetes among schizophrenics (abstract).

References Schizophr Res 2003;60(1 suppl):359-60.

27. Gianfrancesco F, White RE, Yu E. Antipsychotic-induced type 2 dia-

1. Anand G, Burton TM. Drug debate: new antipsychotics pose a quandary betes: evidence from a large health plan database (poster NR400). Pre-

for FDA, doctors. Wall Street Journal 2003;241(April 11):A1, A8. sented at: 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Associa-

2. Erle G, Basso M, Federspil G, Sicolo N, Scandellari C. Effect of chlor- tion, Philadelphia, May 22, 2002.

promazine on blood glucose and plasma insulin in man. Eur J Clin Phar- 28. Wilson DR, Hammond CC, Buckley PF, Petty F, Fernandes P. Atypical an-

macol 1977;11:15-8. tipsychotics and hyperglycemia: an analysis of 11,994 persons treated in

3. Koller E, Schneider B, Bennett K, Dubitsky G. Clozapine-associated di- Ohio DMH hospitals, 1994–2001 (poster). Presented at: 40th Annual

abetes. Am J Med 2001;111:716-23. Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Waiko-

4. Koller EA, Doraiswamy PM. Olanzapine-associated diabetes mellitus. loa, Hawaii, December 9–13, 2001.

Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:841-52. 29. Sernyak MJ, Leslie DL, Alarcon R, Losonczy MF, Rosenheck R. Dr.

5. Koller EA, Cross JT, Doraiswamy PM, Schneider BS. Risperidone-asso- Sernyak and colleagues reply (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:389.

ciated diabetes mellitus: a pharmacovigilance study. Pharmacotherapy 30. Hedenmalm K, Hagg S, Stahl M, Mortimer O, Spigset O. Glucose intol-

2003;23:735-44. erance with atypical antipsychotics. Drug Saf 2002;25:1107-16.

6. Koller EA, Doraiswamy PM, Cross JT, Schneider BS. Quetiapine-asso- 31. Holden RJ, Pakula IS. The link between diabetes and schizophrenia: an

ciated diabetes (poster NR74). Presented at: 156th Annual Meeting of immunological explanation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1999;33:286-7.

the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 17–22, 2003.

32. Citrome L, Volavka J. Optimal dosing of atypical antipsychotics in

7. Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Citrome L, Sheitman B, McEvoy adults: a review of the current evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2002;10:

JP, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol in patients with schizophre- 280-91.

nia treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry

33. Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little

2003;160:290-6.

RR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired

8. Paris RM, Bedno SA, Krauss MR, Keep LW, Rubertone MV. Weighing

glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The Third National Health and Nutri-

in on type 2 diabetes in the military. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1894-8.

tion Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care 1998;21:518-24.

9. Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watch-

34. Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests

ing and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2

and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical

diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 2003;289:1785-91.

trials published in the BMJ. BMJ 2002;325:249-52.

10. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mel-

litus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classifica- 35. Barbieri M, Drummond MF. Conflict of interest in industry-sponsored

tion of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003;(26 suppl 1):S5-20. economic evaluations: real or imagined? Curr Oncol Rep 2001;3:410-3.

11. Taylor DM, McAskill R. Atypical antipsychotics and weight gain — a 36. Yaphe J, Edman R, Knishkowy B, Herman J. The association between

systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101:416-32. funding by commercial interests and study outcome in randomized con-

trolled drug trials. Family Practitioner 2001;18:565-8.

12. Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, Goldberg R, Postrado L, Lucksted A, et

al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia sam- 37. Davidson RA. Source of funding and outcome of clinical trials. J Gen In-

ples. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:903-12. tern Med 1986;1:155-8.

13. Ryan MCM, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance 38. Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Simms RW, Fortin PR, Felson DT, Minaker

in first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry KL, et al. A study of manufacturer-supported trials of nonsteroidal anti-

2003;160:284-9. inflammatory drugs in the treatment of arthritis. Arch Intern Med 1994;

14. Henderson DC. Atypical antipsychotic-induced diabetes mellitus. How 154:157-63.

strong is the evidence? CNS Drugs 2002;16:77-89. 39. Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, Fields KK, Bennett CL, Adams

15. Lindenmayer JP, Nathan AM, Smith RC. Hyperglycemia associated with JR, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research.

the use of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 23):30-8. Lancet 2000;356:635-8.

16. Sowell MO, Mukhopadhyay N, Cavazzoni P, Shankar S, Steinberg HO, 40. Neeleman J. A continuum of premature death. Meta-analysis of compet-

Breier A, et al. Hyperglycemic clamp assessment of insulin secretory re- ing mortality in the psychosocially vulnerable. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:

sponses in normal subjects treated with olanzapine, risperidone, or place- 154-62.

bo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2918-23. 41. Citrome L. Efficacy should drive atypical antipsychotic treatment (let-

17. Lund BC, Perry PJ, Brooks JM, Arndt S. Clozapine use in patients with ter). BMJ 2003;326:283-4.

schizophrenia and the risk of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. 42. Gianfrancesco FD, Grogg A, Mahmoud R, Wang RH, Meletiche D. Dif-

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:1172-6. ferential effects of antipsychotic agents on the risk of development of

18. Sernyak MJ, Leslie DL, Alarcon RD, Losonczy MF, Rosenheck R. As- type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients with mood disorders. Clin Ther

sociation of diabetes mellitus with use of atypical neuroleptics in the 2003;25:1150-71.

treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:561-6. 43. Gianfrancesco FD, White R, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA. Antipsychotic-in-

1856 ■ The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 www.theannals.com

Atypical Antipsychotics and the Development of Diabetes Mellitus

duced type 2 diabetes: evidence from a large health plan database. J Clin CONCLUSIONES: Se recomienda que los médicos manejen el riesgo

Psychopharmacol 2003;23:328-35. regularmente a través de un seguimiento de cerca de todos los pacientes

44. Fuller MA, Shermock KM, Secic M, Grogg AL. Comparative study of recibiendo antipsicóticos atípicos, con el propósito de determinar el

the development of diabetes mellitus in patients taking risperidone and desarrollo de DM. Estudios futuros deben ser controlados

olanzapine. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:1037- 43. cuidadosamente en áreas que pueden ocasionar confusión tales como la

45. Cunningham F, Lambert B, Miller DR, Daluck G, Kim JB, Hur K. An- edad, diagnóstico, cambio en peso, nivel de actividad, historial familiar,

tipsychotic induced diabetes in Veteran schizophrenic patients (abstract). y etnicidad.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12(1 suppl):S154-5.

46. Goode E. 3 schizophrenia drugs may raise diabetes risk, study says. The Brenda R Morand

New York Times 2003;153(August 25):A8.

47. Rosack J. FDA to require diabetes warning on antipsychotics. Psychiatr

RÉSUMÉ

News 2003;38(20):1.

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of diabetes and OBJECTIF: Réviser les preuves pharmacoépidémiologiques reliant

impaired fasting glucose in adults — United States, 1999–2000. MMWR l’exposition aux antipsychotiques atypiques au développement du

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:833-7. diabète mellitus.

REVUE DE LITTÉRATURE: Une recherche MEDLINE (1990–mars 2003) a

été effectuée pour retrouver les études pharmacoépidémiologiques

traitant du lien entre l’exposition aux antipsychotiques atypiques et le

développement du diabète mellitus.

EXTRACTO

SÉLECTION DES ÉTUDES ET SÉLECTION DE L’INFORMATION: La recherche a

OBJETIVO: Repasar la evidencia farmacoepidemiológica para el enlace

été limitée aux papiers qui décrivaient les résultats des analyses de

entre la exposición a antipsicóticos atípicos y el desarrollo de diabetes grandes bases de données et qui utilisaient dans le titre ou le résumé les

mellitus (DM). mots diabetes ou hyperglycemia ou antipsychotics ou clozapine ou

FUENTES DE INFORMACIÓN: Se condujo una búsqueda en MEDLINE olanzapine ou risperidone ou quetiapine ou ziprasidone ou aripiprazole.

(1990–marzo 2003) con relación a estudios farmacoepidemiológicos On a extrait de ces analyses le rapport de cotes ou le risque relatif et leur

explorando el enlace entre la exposición a los antipsicóticos atípicos y el intervalle de confiance respectifs.

desarrollo de DM. RÉSUMÉ: Les résultats sont contradictoires, et cette variabilité peut être

SELECCIÓN DE FUENTES Y MÉTODO DE EXTRACCIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN: La due aux différences au niveau des populations étudiées et au niveau des

investigación estuvo limitada a los artículos describiendo los hallazgos devis expérimentaux utilisés ainsi qu’à la possibilité de biais de

de los análisis de bases de datos extensas y que utilizaron las palabras publication liés au financement par des compagnies pharmaceutiques.

diabetes o hiperglicemia, y antipsicótico o clozapina u olanzapina o Néanmoins, une augmentation du risque de diabète mellitus semble être

risperidona o quetiapina o ziprasidona o aripiprazol en el título o en el présente chez les patients recevant des antipsychotiques atypiques.

extracto. La proporción de la probabilidad o el riesgo relativo, junto con Cependant, le risque différentiel entre les antipsychotiques atypiques est

sus intérvalos de confidencia correspondientes, fueron extraídos. difficile à établir.

SÍNTESIS: Los resultados evaluados son conflictivos, y esta variabilidad CONCLUSIONS: Il est suggéré aux cliniciens de contrôler le risque en

se puede deber a las diferentes poblaciones estudiadas, a los diferentes surveillant de façon régulière l’émergence de diabète mellitus chez tous

diseños de los estudios, y a la posibilidad de parcialidad de publicación les patients recevant des antipsychotiques atypiques. Les études futures

relacionada a la provisión de fondos por la industria farmacéutica. No devraient soigneusement contrôler les éléments confondants tels l’âge, le

obstante, un riesgo incrementado para el desarrollo de DM parece estar diagnostic, le changement de poids, le niveau d’activité, les antécédents

presente en pacientes que están recibiendo antipsicóticos atípicos. Sin familiaux, et l’ethnie.

embargo, el riesgo diferencial entre los antipsicóticos atípicos es difícil

de determinar. Marie Larouche

www.theannals.com The Annals of Pharmacotherapy ■ 2003 December, Volume 37 ■ 1857

You might also like

- Hypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionFrom EverandHypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionNo ratings yet

- Congenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandCongenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementDiva D. De León-CrutchlowNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutDocument7 pagesMedicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutGrady CoolNo ratings yet

- ResponseConsensusReportAntipsychoticsMetabolicIssuesLetter CITROME DiabCare2004Document5 pagesResponseConsensusReportAntipsychoticsMetabolicIssuesLetter CITROME DiabCare2004Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) in Decreasing Blood Sugar Levels Among Patients With Impaired Fasting Glucose in Antipolo CityDocument4 pagesThe Efficacy of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) in Decreasing Blood Sugar Levels Among Patients With Impaired Fasting Glucose in Antipolo CityMa. Isabel AzañaNo ratings yet

- Medication-Induced Diabetes MellitusDocument6 pagesMedication-Induced Diabetes MellitusAmjadNo ratings yet

- RosperidonDocument7 pagesRosperidonEndang SusilowatiNo ratings yet

- Renal and Retinal Effects of Enalapril and Losartan in Type 1 DiabetesDocument12 pagesRenal and Retinal Effects of Enalapril and Losartan in Type 1 DiabetesDina Malisa Nugraha, MDNo ratings yet

- FDA AnalysisDocument7 pagesFDA AnalysisRidha Surya NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Journal 1 Nejmoa1506930Document11 pagesJournal 1 Nejmoa1506930Dyo O RNo ratings yet

- 2 DyslipidemiaDocument7 pages2 DyslipidemiaShengyou ZengNo ratings yet

- Prader-Willy Fda OzempicDocument16 pagesPrader-Willy Fda OzempicJailza MartinsNo ratings yet

- Geographic and Clinical Variation in Clozapine Use in The United StatesDocument7 pagesGeographic and Clinical Variation in Clozapine Use in The United StatesEvaG2012No ratings yet

- Retinopathy DiabeticDocument5 pagesRetinopathy DiabeticMagnaNo ratings yet

- Psychopharmacologictreatment Ofpsychosisinchildrenand AdolescentsDocument18 pagesPsychopharmacologictreatment Ofpsychosisinchildrenand AdolescentsbogdancoticaNo ratings yet

- DEPICT 1 - T1D StudyDocument13 pagesDEPICT 1 - T1D StudyGVRNo ratings yet

- PCOS and Metabolic SyndromeDocument21 pagesPCOS and Metabolic SyndromeHAVIZ YUADNo ratings yet

- Righi (2016)Document6 pagesRighi (2016)PelagyalNo ratings yet

- Weight Loss Drug Cutting Risk of Heart AttackDocument12 pagesWeight Loss Drug Cutting Risk of Heart AttackWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity Without DiabetesDocument12 pagesSemaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity Without Diabetesmengyanli.528No ratings yet

- Igweokpala, 2023Document11 pagesIgweokpala, 2023Mirilláiny AnacletoNo ratings yet

- Chap 1Document3 pagesChap 1Samreen JawaidNo ratings yet

- The Pubertal Presentation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome PCOS 2002 Fertility and SterilityDocument1 pageThe Pubertal Presentation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome PCOS 2002 Fertility and SterilityfujimeisterNo ratings yet

- Pioglitazone After Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic AttackDocument11 pagesPioglitazone After Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic AttackBiola DwikoNo ratings yet

- Lipid Lowering DrugsDocument2 pagesLipid Lowering DrugsstambicaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EscitalopramDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Escitalopramc5swkkcn100% (1)

- Nonalcoholic SteatohepatitisDocument15 pagesNonalcoholic SteatohepatitisLucas VenturaNo ratings yet

- Medip, IJCP-2856 ODocument6 pagesMedip, IJCP-2856 OMarcelita DuwiriNo ratings yet

- ASCP Corner Increased Risk of Cerebrovascular Adverse Events and Death in Elderly Demented PatienDocument1 pageASCP Corner Increased Risk of Cerebrovascular Adverse Events and Death in Elderly Demented PatienSantosh KumarNo ratings yet

- SPW Diazoxide CholinDocument10 pagesSPW Diazoxide CholinlailagsazNo ratings yet

- Potent Antihypertensive Action of Dietary Flaxseed in Hypertensive PatientsDocument13 pagesPotent Antihypertensive Action of Dietary Flaxseed in Hypertensive PatientsMaRiana TorresNo ratings yet

- Use of Very-High-Dose Olanzapine in Treatment-Resistant SchizophreniaDocument4 pagesUse of Very-High-Dose Olanzapine in Treatment-Resistant SchizophreniaPutu Agus GrantikaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Chlorpromazine and Haloperidol Combination on Lipid LevelsDocument10 pagesEffect of Chlorpromazine and Haloperidol Combination on Lipid LevelstrianaamaliaNo ratings yet

- Revista Medica ChilenaDocument10 pagesRevista Medica ChilenaMayita DurNo ratings yet

- High-Intensity Statins Are Associated With Increased Incidence of Hypoglycemia During Hospitalization of Individuals Not Critically IllDocument6 pagesHigh-Intensity Statins Are Associated With Increased Incidence of Hypoglycemia During Hospitalization of Individuals Not Critically IllNermine S. ChoumanNo ratings yet

- Donepezil in Vascular Dementia: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled StudyDocument9 pagesDonepezil in Vascular Dementia: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled StudyDian ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Gebhardt2007 Article ClozapineOlanzapine-InducedRecDocument5 pagesGebhardt2007 Article ClozapineOlanzapine-InducedRecrossibNo ratings yet

- Bauch-Atrial Natriuretic Peptide As A MarDocument6 pagesBauch-Atrial Natriuretic Peptide As A MarSzendeNo ratings yet

- Clozapine and Haloperidol in ModeratelyDocument8 pagesClozapine and Haloperidol in Moderatelyrinaldiapt08No ratings yet

- Clinical Course of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Hypertriglyceridemic Pancreatitis Pancreas 2015Document4 pagesClinical Course of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Hypertriglyceridemic Pancreatitis Pancreas 2015América FloresNo ratings yet

- Jama Slomski 2021 JN 210028 1637771580.15064Document1 pageJama Slomski 2021 JN 210028 1637771580.15064Luis Adrian Rivera PomalesNo ratings yet

- Tsuyuki 2002Document7 pagesTsuyuki 2002Basilharbi HammadNo ratings yet

- Whats New of PcosDocument9 pagesWhats New of PcosbambangNo ratings yet

- Hormone Therapy in Postmenopausal WomenDocument8 pagesHormone Therapy in Postmenopausal WomenChyntia Pramita SariNo ratings yet

- Focus On The Clinical Ramifications of Antipsychotic Choice For The Risk For Developing Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument5 pagesFocus On The Clinical Ramifications of Antipsychotic Choice For The Risk For Developing Type 2 Diabetes MellitusLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Funcion RenalDocument11 pagesFuncion RenalCarlos AvalosNo ratings yet

- Addition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors To Sulphonylureas and Risk of Hypoglycaemia: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesAddition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors To Sulphonylureas and Risk of Hypoglycaemia: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisEmanuel BaltigNo ratings yet

- Emailing Expression of KGF-1 and KGF-2 in Skin Wounds ADocument12 pagesEmailing Expression of KGF-1 and KGF-2 in Skin Wounds ARimaWulansariNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes With Efpeglenatide in Type 2 DiabetesDocument12 pagesCardiovascular and Renal Outcomes With Efpeglenatide in Type 2 DiabetesMoeez AkramNo ratings yet

- Eria 2Document11 pagesEria 2ruth angelinaNo ratings yet

- Ajp.161.10.1837 2Document11 pagesAjp.161.10.1837 2HKANo ratings yet

- Hypoglycemia - 2014 Morales N DoronDocument8 pagesHypoglycemia - 2014 Morales N DoronDian Eka RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- P 007 OlanzapineDocument11 pagesP 007 OlanzapineBalasubrahmanya K. R.No ratings yet

- Lo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesLo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAprilia R. PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Gap in DiabetesDocument3 pagesKnowledge Gap in Diabetesamit545No ratings yet

- Soal PG Endokrin MahasiswaDocument5 pagesSoal PG Endokrin MahasiswaSandwingNo ratings yet

- 23 Ifteni Tit Rápida 1 Acta - Psychiatrica - Scandinavica - 2014 - 130 - (1) - 25Document5 pages23 Ifteni Tit Rápida 1 Acta - Psychiatrica - Scandinavica - 2014 - 130 - (1) - 25observacionfray23No ratings yet

- Clotiapine - Another Forgotten Treassure in PsychiatryDocument1 pageClotiapine - Another Forgotten Treassure in PsychiatryJuan IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Platelet Activating FactorDocument8 pagesPlatelet Activating FactorayesayeziaNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 18: PsychiatryFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 18: PsychiatryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ZolpidemProductLabel 0819 PDFDocument7 pagesZolpidemProductLabel 0819 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- TriazolamProductLabel 1019 PDFDocument13 pagesTriazolamProductLabel 1019 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- See Full Prescribing Information For Complete Boxed WarningDocument14 pagesSee Full Prescribing Information For Complete Boxed WarningLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- RamelteonProductLabel 1218 PDFDocument18 pagesRamelteonProductLabel 1218 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- DoxepinSleepProductLabel 0310 PDFDocument4 pagesDoxepinSleepProductLabel 0310 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Restoril™ (Temazepam) Capsules USP RX Only Warning: Risks From Concomitant Use With OpioidsDocument14 pagesRestoril™ (Temazepam) Capsules USP RX Only Warning: Risks From Concomitant Use With OpioidsLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- DoxepinSleepProductLabel 0310 PDFDocument4 pagesDoxepinSleepProductLabel 0310 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- ZolpidemProductLabel 0819 PDFDocument7 pagesZolpidemProductLabel 0819 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- RamelteonProductLabel 1218 PDFDocument18 pagesRamelteonProductLabel 1218 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

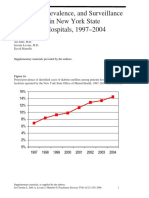

- Incidence and Prevalence of Diabetes in NY Psychiatric Hospitals 1997-2004Document5 pagesIncidence and Prevalence of Diabetes in NY Psychiatric Hospitals 1997-2004Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- TriazolamProductLabel 1019 PDFDocument13 pagesTriazolamProductLabel 1019 PDFLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- See Full Prescribing Information For Complete Boxed WarningDocument14 pagesSee Full Prescribing Information For Complete Boxed WarningLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- WhatIsTranscranialMagneticStimulation CITROME KlineLine1999Document1 pageWhatIsTranscranialMagneticStimulation CITROME KlineLine1999Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Diabetes prevalence trends in NY mental hospitalsDocument8 pagesDiabetes prevalence trends in NY mental hospitalsLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- IncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster For Distribution CITROME CINP2006Document1 pageIncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster For Distribution CITROME CINP2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- IncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster For Distribution CITROME CINP2006Document1 pageIncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster For Distribution CITROME CINP2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- CATIENNTEditorialRegardingCITROME KERWIN IntJClinPract2006Document2 pagesCATIENNTEditorialRegardingCITROME KERWIN IntJClinPract2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- NR330 Efficacy of Ziprasidone Against Hostility in SchizophreniaDocument1 pageNR330 Efficacy of Ziprasidone Against Hostility in SchizophreniaLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- OlanzapineHighDoseRCTHGLFPoster KINON CINP2006Document19 pagesOlanzapineHighDoseRCTHGLFPoster KINON CINP2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION (Continued)Document1 pageINTRODUCTION (Continued)Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- IncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster CITROME NCDEU2006Document1 pageIncidencePrevalenceSurveillanceDiabetesMellitusInpatientsPoster CITROME NCDEU2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Ziprasidone efficacy against hostility in schizophreniaDocument1 pageZiprasidone efficacy against hostility in schizophreniaLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Catechol-O-methyltransferase and Monoamine Oxidase-A Polymorphisms and Treatment Response To Typical and Atypical NeurolepticsDocument3 pagesCatechol-O-methyltransferase and Monoamine Oxidase-A Polymorphisms and Treatment Response To Typical and Atypical NeurolepticsLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- ReducingInpatientAggressionPayingAttentionPaysOffPoster NOLAN APA2006Document1 pageReducingInpatientAggressionPayingAttentionPaysOffPoster NOLAN APA2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Benefits of A Second Dose of Intramuscular (IM) Aripiprazole To Control Agitation in Patients With Schizophrenia or Bipolar I DisorderDocument1 pageBenefits of A Second Dose of Intramuscular (IM) Aripiprazole To Control Agitation in Patients With Schizophrenia or Bipolar I DisorderLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- OlanzapineEarlyPredictorsWeightGainBipolarDisorder LIPKOVICH JClinPsychopharm2006Document5 pagesOlanzapineEarlyPredictorsWeightGainBipolarDisorder LIPKOVICH JClinPsychopharm2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Sscchhiizzoopphhrreenniiaa: Ccuurrrreenntt Ttrreeaattm Meenntt CcoonnssiiddeerraattiioonnssDocument4 pagesSscchhiizzoopphhrreenniiaa: Ccuurrrreenntt Ttrreeaattm Meenntt CcoonnssiiddeerraattiioonnssLeslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- QuetiapineAntiaggressiveAgentCaseReport CITROME JCP2001Document1 pageQuetiapineAntiaggressiveAgentCaseReport CITROME JCP2001Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- MedicalTrainingUnitedStatesAddendum CITROME CMAJ1992Document2 pagesMedicalTrainingUnitedStatesAddendum CITROME CMAJ1992Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- DiabetesSchizophreniaInterview CITROME BehavHealthCare2006Document8 pagesDiabetesSchizophreniaInterview CITROME BehavHealthCare2006Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument7 pagesDrug StudyJohn Paulo MataNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument7 pagesSchizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders Clinical Practice GuidelineDani NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Neurology Board Review-THIRD EDITIONDocument44 pagesComprehensive Neurology Board Review-THIRD EDITIONDr. Chaim B. Colen50% (4)

- Assessment and Emergency Management of The Acutely Agitated or Violent Adult - UpToDateDocument20 pagesAssessment and Emergency Management of The Acutely Agitated or Violent Adult - UpToDateImja94100% (1)

- Schizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDocument16 pagesSchizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDimas Januar100% (2)

- Tehreem - Recalls MODIFIED BY Me & AARAVDocument58 pagesTehreem - Recalls MODIFIED BY Me & AARAVRohini SelvarajahNo ratings yet

- GNC Psy Nursing QuestionsDocument34 pagesGNC Psy Nursing QuestionsFan Eli100% (1)

- Antipsychotic Drugs Grandiosity Hallucinations Paranoia DelusionsDocument63 pagesAntipsychotic Drugs Grandiosity Hallucinations Paranoia DelusionsMuhammad Masoom Akhtar100% (1)

- 1.schizophrenia An Overview PDFDocument5 pages1.schizophrenia An Overview PDFNadyaNo ratings yet

- Injection SOP 2011 (3rd Edition)Document70 pagesInjection SOP 2011 (3rd Edition)lynlgsxrNo ratings yet

- SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesSchizophreniaMANOJ KUMARNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Guide EN PDFDocument79 pagesSchizophrenia Guide EN PDFMichaelus1No ratings yet

- First Generation AntipsychoticDocument4 pagesFirst Generation AntipsychoticPutu Agus Grantika100% (1)

- Psychopharmacology in PsychiatryDocument94 pagesPsychopharmacology in PsychiatryOslo SaputraNo ratings yet

- Third Generation Antipsychotic DrugsDocument45 pagesThird Generation Antipsychotic DrugsGabriela Drima100% (1)

- Antipsychotic: Antipsychotics, Also Known As NeurolepticsDocument28 pagesAntipsychotic: Antipsychotics, Also Known As NeurolepticsJussel Vazquez MarquezNo ratings yet

- Drug Study 2019Document14 pagesDrug Study 2019Aubrey Unique Evangelista100% (1)

- Extrapyramidal Symptoms Guide: Dystonia, Akathisia, Parkinsonism & Tardive DyskinesiaDocument35 pagesExtrapyramidal Symptoms Guide: Dystonia, Akathisia, Parkinsonism & Tardive DyskinesiaLucas PhiNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Psychiatric Drugs 08 PDFDocument275 pagesHandbook of Psychiatric Drugs 08 PDFlucian_vatamanu100% (3)

- Schizophrenia Diagnosis, Symptoms & Treatment /TITLEDocument50 pagesSchizophrenia Diagnosis, Symptoms & Treatment /TITLEelvinegunawanNo ratings yet

- Psychopharmacological AgentsDocument44 pagesPsychopharmacological Agentsbazet49No ratings yet

- Neuroleptics & AnxiolyticsDocument65 pagesNeuroleptics & AnxiolyticsAntonPurpurovNo ratings yet

- Perspectives in Pharmacology: Roger D. Porsolt, Vincent Castagné, Eric Hayes, and David VirleyDocument5 pagesPerspectives in Pharmacology: Roger D. Porsolt, Vincent Castagné, Eric Hayes, and David Virleyel egendNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology 2nd Edition Nolen-Hoeksema Test Bank 1Document52 pagesAbnormal Psychology 2nd Edition Nolen-Hoeksema Test Bank 1jamie100% (31)

- Psychotropic Medications During PregnancyDocument20 pagesPsychotropic Medications During PregnancyMaria Von ShaftNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 1999 PDFDocument8 pages2018 Article 1999 PDFyusma haranisNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Drugs: Presentation By-Sumaiya SadafDocument19 pagesAntipsychotic Drugs: Presentation By-Sumaiya SadafSweta ShahNo ratings yet

- Archives of Clinical Psychiatry - R de Psiquiatria - Vol. 47 - 6 - 2020Document63 pagesArchives of Clinical Psychiatry - R de Psiquiatria - Vol. 47 - 6 - 2020Danilo Pereira GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Which Drugs Can Cause Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome?: Medicines Q&AsDocument6 pagesWhich Drugs Can Cause Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome?: Medicines Q&AsLaily MasrurohNo ratings yet