Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arqueología de La Cultura Hanseática en El Báltico - David Gaimster

Uploaded by

dailearon3110Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arqueología de La Cultura Hanseática en El Báltico - David Gaimster

Uploaded by

dailearon3110Copyright:

Available Formats

A Parallel History: The Archaeology of Hanseatic Urban Culture in the Baltic c.

1200-1600

Author(s): David Gaimster

Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 37, No. 3, Historical Archaeology (Sep., 2005), pp. 408-423

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40024244 .

Accessed: 26/09/2014 10:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World

Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history: the archaeology of

Hanseatic urban culture in the Baltic

c. 1200-1 600

David Gaimster

Abstract

The Hansa formed the principal agent of trade and cultural exchange in northern Europe and the

Baltic during the late medieval to early modern periods. Hanseatic urban settlements in northern

Europe shared many things in common. Their cultural 'signature' was articulated physically through

a shared vocabulary of step-gabled brick architecture and domestic goods. Although the Hansa

remains a monolith in the popular historical imagination, it is rapidly becoming a multidisciplinary

field of study juxtaposing often-contradictory material and documentary sources. The redevelop-

ment of towns on the Baltic littoral, particularly of those formerly behind the Iron Curtain, offers

archaeological opportunities to create parallel biographies of medieval mercantile communities that

avoid tautology but bring a new texturing to the reconstruction of cultural development in the

region. The archaeology of the Hansa in the Baltic - as a case study in historical archaeology - offers

the prospect of investigating some of the key attributes of pre-industrial European society on the

macro-regional scale. Such attributes include the development of mercantile capitalism, Europea-

nization, colonialism, acculturation and resistance. Ceramic distributions are particularlysensitive to

reflecting levels of adoption and resistance to Hanseatic cultural influences among diverse

communities, notably in the spheres of dining practice and domestic comfort. The paper begins

with a review of historical perceptions of Hansa culture in the region and how rescue excavation is

now redefining a sense of identity among local communities in a changing geo-political environment.

Keywords

Hansa; historical archaeology; public archaeology; identity; mercantilism; acculturation; resistance;

proto-colonialism; domestic ceramics: redware, stoneware, maiolica, tile-stoves.

Introduction

Although the Hansa remains, even today, a monolith in the popular historical

imagination of northern and western Europe, the rapid redevelopment of towns in the

I) Routledqe WorldArchaeology Vol. 37(3): 408^23 HistoricalArchaeology

IV TayioraFrandscroup © 2005 Taylor & Francis ISSN 0043-8243 print/ 1470- 1375 online

DOI: 10.1080/00438240500168483

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 409

Baltic Sea region following the fall of the Iron Curtain is rapidly transforming it into a

multidisciplinary field of study, juxtaposing the results of recent excavation against the

established documentary, iconographic and architectural record (Plate 1). The

archaeology of the Hanseatic trading town in the Baltic, with its prodigious and well-

preserved artefact sequences, offers the prospect of investigating some key attributes of

pre-industrial European society on the macro-regional scale. Such attributes include the

development of mercantilism, Europeanization, colonialism, adoption and resistance.

Taking domestic ceramics as a case study, this paper will explore the transfer of western

European or 'Hanseatic' lifestyles into the region between c.1200 and 1600 and the

extent to which some communities resisted them, notably in the spheres of dining

practice and domestic heating technology. This analysis of the Hanseatic urban culture

in the Baltic provides a potential model for study of European cultural and

technological networks in the New World.

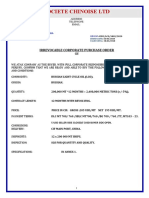

Plate1 Rescuearchaeologyin advanceof majorinfrastructure

developments.Szczecinharbourarea,

Poland.Photographby author.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

410 David Gaimster

This artefact-based approach is essentially complementary in character to the primary

historical sources and concerns itself with profiling the emergence of a German-style

'Hanseatic' mercantile culture on the Baltic littoral during the late Middle Ages. Through

the record of ceramic consumption, it seeks to establish the degree to which geographically

disparate urban communities became culturally and technologically homologous in the

home, at various social levels, through the medium of long-distance commercial contact,

irrespective of Hanseatic League membership or official corporate status. Thus the term

'Hanseatic' is used here for its value as an index of acculturation, not in its traditional

political sense (Gaimster 1993). Following in the tradition of European historical

archaeology, the paper will explore the active role of artefacts in creating a 'parallel'

cultural history for the region, which may generate conclusions of historical interest

independent of the established written narrative (Andren 1997: 25-36). For northern

Europe the surviving documents are notoriously deficient in socially sensitive cultural

information. This complementary approach to the history of the Hanseatic town is already

well established in the art-historical sphere (Schildhauer 1985; Zaske and Zaske 1986; von

Bonsdorff 1993).

In addition to creating a new understanding of culture contact in the Baltic during the

late Middle Ages and its immediate aftermath, urban rescue archaeology is also helping to

reshape cultural identity in the region. Previously, with its strong Teutonic overtones and

association with the rise of the western European capitalist bourgeoisie, the Hansa was

largely censored from the historical record in the former East, as new studies of former

public archaeological policy in the region are revealing. This paper begins by assessing

past perceptions and the impact of recent excavations on local communities and their

collective sense of place in the New European framework.

Public archaeology and reshaping cultural identity in the Baltic

Every age, it seems, appropriates the Hansa for its own ends (Hackmann 1996). German

imperialists of the 1870s emphasized their claim to maritime hegemony through reference

to the might of the German Hansa. Pre-World War 1 German commentators spoke of the

moral virtues of a Hanseatic-Prussian Germany and considered the Hohenzollen-Prussian

Germany as having inherited the Hansa. In the inter-war and war periods the connections

between the Hansa and the German ethnic settlements in Poland and the Baltic States

provided a motivation for the National Socialists to resist Sovietization and justify re-

conquest and Lebensraum to the East. The message was captured in an iconic history

painting executed in 1942 by Fritz Grotemeyer in which a wagon train of Hanseatic

merchants in the style of a classic Hollywood Western scene treks to a promised land in the

East (Jaacks 1989).

From the end of World War II to the fall of the Iron Curtain, the Hansa, with its strong

Teutonic undertones and association with the development of the urban bourgeoisie, was

largely censored from the historical record in the former East, particularly in the sphere of

public heritage, as new studies of state archaeological policy in the region are revealing. By

way of illustration, in former areas of central Soviet authority, such as in Konigsberg

(Kaliningrad, which is still part of the modern Russian Federation), iconic monuments of

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 41 1

the Hanseatic trading city, such as the city's fortifications, were ruthlessly demolished as

late as 1968 (Lange 2001). Today empty scrubland marks the site of the former town castle

and historic urban core.

A negative response has also been experienced in other areas of post-war Soviet

influence. Excavations on the town hall square in the centre of Tallinn, Estonia, during

the early 1950s were undertaken with the express intention (it now emerges, thanks to

new research by Jaak Mall and Erki Russow (2003)), of denying 'bourgeois theories on

the foundation of the city by Danish and German settlers in the thirteenth century in

favour of "the ancient and deep cultural relationship between the Estonian and Russian

nations'". According to the original excavators, Tallinn emerged as a settlement in the

tenth century and developed into a town in the twelfth century, before the arrival of the

colonists. Recent re-analysis of the finds from the site revealed no evidence of pre-

thirteenth-century occupation and detected the full Hanseatic 'signature' among the site

finds assemblage.

Despite almost slavish reconstruction of the Gdansk Altstadt in the immediate post-war

period, until the early 1990s Polish urban histories were imbued with the popular view that

the German Hansa exploited native populations in a colonial manner (e.g. Cieslak and

Biernat 1988: 39). However, increasingly today, the legacy of the Hansa provides a

motivation for economic regeneration of former trading towns on the Pomeranian Baltic

coast. In the Elblag Altstadt, apart from the churches, a hospital and six houses, World

War II left behind a black hole in the centre of the modern city. Here an innovative

partnership between developers, town planners, historic buildings conservators and local

archaeologists is enabling modern Hanseatic 'merchant houses' to be built precisely on the

foundations of the former tenements in order to recreate the medieval townscape, in plan,

elevation and in panorama (Lubocka-Hoflmann 1997). Facade, internal configuration and

use are carefully prescribed by the local authority, which, in turn, postpones development

for up to three years for the purpose of full archaeological investigation. Since the 1980s 5

per cent of the total area of the Altstadt has been investigated archaeologically. The

emerging silhouette is forming a model for reconstruction in the neighbouring Hansa ports

of Szczecin and Kolobrzeg. The entire neighbourhood near to the harbour at Szczecin,

with its recently restored medieval town hall, is being entirely reconstructed from World

War II dereliction.

Acknowledgement of the importance of the Hanseatic built heritage can perhaps be best

seen in the award in 2002 of World Heritage status to the North German trading ports of

Wismar and Stralsund, as exemplars of the secular brick Gothic architecture in the Baltic

and in recognition of their contribution to global culture of the seafaring Hanseatic

League. The development typifies the profound transformation in local public perceptions

of the Hansa. Previously, under the DDR regime, the Hansa port Mecklenburg-Lower

Pomerania was neglected to the point of dereliction (only Rostock was significantly

damaged in World War II), mainly for lack of economic resources, and due to an

institutional preference for (politically correct) rural prehistoric archaeology. In

Greifswald we see what was done when resources were available to the State. Here,

between the late 1970s and late 1980s, entire quarters of its well-preserved 50ha Altstadt

were flattened in order to make way for public housing. In fact, 10 per cent of the historic

fabric of the town was lost.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

412 David Gaimster

The Hansa in the Baltic: economic, cultural and technological networks

The Hansa was a loose confederation of German cities acting as principal agents of trade

and exchange in northern Europe and the Baltic during the medieval to early modern

period. Lubeck, founded in 1158, became an important member of the association. In the

wake of conquest by the Teutonic Order, German merchants rapidly colonized the lands

to the east during the course of the following century and founded such towns as Rostock,

Stralsund, Gdansk and Riga. The Hanseatic trading system reached its zenith during the

fourteenth to fifteenth centuries with the foundation of permanent trading posts or

Kontoreconnecting the periphery of northern Europe to the western and central European

core. It drew the west, the east and the north of the continent together by acting as an

intermediaryfor the exchange of goods between two very different patterns of production:

raw materials from the east and finished/semi-finished products from the west, and by

stimulating the wider long-distance market. Despite their dispersed geographical position,

a new type of ship, the cog, which developed around 1250, enabled the Hanseatic

merchants to maintain economic superiority over much of the continent for centuries. This

ship was more capacious and more stable than previous models and, at around 200-300

tons, could carry two to three times the cargo.

As influential in the growing economic dominance of the Hanseatic League in the north,

perhaps more so than geographical advantage or technological superiority, were the social

and genealogical links which developed between trading partnersand towns and families the

length and breadth of northern Europe. Merchants' reciprocal enterprises, networks based

on kinship and council organization, clearly boosted long-distance trade in comparison to

previous centuries. Literacy, primarily for the recording of transactions, was introduced by

the Hansa merchants across the urban trading populations of northern Europe.

The movement of raw and processed material and finished goods inevitably also

necessitated the journeying to and fro of people. In addition to traders, wholesalers and

retailers, members of the aristocracy, administrators, soldiers, churchmen and, crucially,

craftsmen - shipbuilders, altarpiece-carversand potters - were prepared to migrate long

distances, with the prospect of exploiting new markets for their products. Thus, perhaps as

influential as the growing economic and technological dominance of the Hansa were the

'horizontal' cultural networks, which developed between trading partners, towns and

families the length and breadth of the Baltic region. By being part of the Hansa trade

network, communities on the periphery became more closely linked to the core. The

Hansa formed a major vehicle of Europeanizaton in the north during the late medieval to

early modern periods.

Hanseatic urban settlements in northern Europe shared many things in common, not

only in their commercial function, but also in their use of lower German dialect and their

cultural and ethnic identity. Recently, art historians have begun to talk in defining terms of

a cosmopolitan Hanseatic signature, which was articulated physically through a shared

vocabulary of town plan (characterized by narrow alleys running from the waterfront to

the central marketplace), commercial public buildings, a distinctive architectural style of

step-gabled brick secular buildings (Backsteingotik)that survive today in merchant houses

(Figure 1), town halls, cloth halls and town gates, church layout (designed as much for

business meetings as for the veneration of the saints), and through common design in the

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 413

Figure1 Step-gabledbrickmerchanthouses on the Hopfenmarkt,Rostock, North Germany,as

depicted in the local merchantVicke Schorler'sillustratedchronicle of the city c. 1578-86.

StadtarchivHansestadtRostock.

visual arts, particularly in the ecclesiastical sphere (Zaske and Zaske 1986). The form of

carved and painted altarpieces endowed by leading merchant families or guilds, carved

bench- and pew-ends, monumental grave slabs and baptismal fonts and doors in cast

bronze all allude to the shared religious and social values of the urban bourgeois elite of

the region.

Impact of archaeology

But what of the private sphere behind the gabled facade of the merchant house? So little of

the traditional histories of the Hansa trading town has been concerned with the conditions

and routines of everyday life among its inhabitants. Where questions of standards of living

and domestic comfort in the Hanseatic urban household have been considered, the

emphasis has inevitably been restricted to probate inventories and to museum survivals of

precious and base metalware, textiles or furniture (Hasse 1979). In 1989 the Hamburg

Museum for History hosted a major international exhibition on the history of the Hansa

entitled Die Hanse: Lebenswirklichkeitund Mythos (Bracker 1989). Although the show

contained thousands of artefacts and works of art, they were used principally to

supplement the primary historical discussions of civic foundation and trade agreements.

The exhibition omitted any discussion of how archaeology has transformed our

knowledge of the Hanseatic town and its cultural profile.

Excavation, by contrast, offers the opportunity to amplify this previously narrow

narrative, particularly in the sphere of domestic lifestyle as reflected in dining practices,

recreational activities and in the structures, layout and decoration of living spaces: all

important measures of social behaviour and cultural identity. The biennial conference of

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

414 David Gaimster

medieval archaeologists from key Hanseatic towns around the North Sea and Baltic held

in Liibeck, and the occasional seminar series on the medieval Baltic town, are among the

first attempts to initiate some synthesis of the 'finds mountain' that is now being generated

by urban development in the region. The first four proceedings deal with research issues,

trade, buildings archaeology and urban infrastructure(Liibecker Kolloquiumsbande 1997,

1999, 2001, 2004; see also Evans 2004 for review).

The recent public exhibitions and publications on the latest urban finds of ceramics,

glass, metalware and organic products from key medieval mercantile centres such as Lund

(Wahloo 1999), Stockholm (Hallerdt 2002) and Turku (Ahola et al 2004) illustrate the

manner in which the archaeological record is transforming the cultural history of the

Hanseatic Baltic town, at both the regional and the micro-scale level. Meanwhile, the

investigation of shipwrecks and their cargoes in the Oresund at the mouth of the Baltic,

along the coasts of Mecklenburg-Lower Pomerania and in the Finnish archipelagos, is

helping to map the content, direction and mechanisms of the maritime trade in finished

western European commodities that linked the ports and people of the region (Gaimster

2000a). These are the objects that created and cemented the cultural identity of urban

mercantile communities on the Baltic rim.

Case-study: the Baltic ceramic market c. 1200-1600

With their short lifespan, ubiquity on the ground and distribution across diverse social

contexts, ceramics can be cross-examined as cultural documents (Kulturtrtiger) in their

own right in the Hanseatic urban milieu (Stephan 1996; Verhaeghe 1998). Uniquely among

the regional finds assemblages of the late medieval to early modern period, ceramics are

represented on virtually all sites, from castles to merchant house. While it is unrealistic to

reconstruct the incomings and outgoings of Hanseatic commodity trade in the North Sea

and Baltic through sherds of pottery, of all the mass materials excavated, ceramic imports

have the best potential to provide a physical measure of cultural contact with the West, in

particular the rate by which Western technologies and domestic practices were assimilated

or rejected by diverse social groups in the region.

The archaeology of the Baltic medieval town also forms a laboratory for the

investigation of technological transfer between the south and west on one side and

Fennoscandia on the other. Through chemical analysis of pottery fabrics, it is becoming

increasingly clear that potters from western Europe migrated around the Baltic rim to

service the new urban markets opening up in northern Germany and on the edges of the

kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden. The archaeological evidence for red earthenware

production, both of highly decorated tableware in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries

and of stove-tiles in the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, reflects the degree to which

Hanseatic communities became self-sufficient in these essential domestic utensils (Schafer

1997; Gaimster 1999a). In this sense Hanseatic towns on the Baltic rim were centres of

technological exchange and innovation. With their commercial function linking the region

to long-distance trade networks, Baltic ports attracted new ideas, fashions, technologies

and industries from outside. Growing populations generated new levels of demand and

competition which, in the case of red earthenware ceramics, stimulated local manufacture.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 415

In terms of numbers, late medieval ceramic trade in the Baltic is dominated by the

competition between stoneware producers in the Rhineland, Lower Saxony and Saxony

(Gaimster 1997: ch.3.3, 1999c). In contrast to the relative fragility of red earthenware, its

robust body enabled stoneware to be transported in bulk and over long distances, as the

discovery of the extensive early fourteenth-century cargo of Rhenish and Lower Saxon

stoneware on the wreck of a coastal trading ship found at Nauvo (Egelskar) in the

archipelago to the south of Turku (Abo) has recently demonstrated (Gaimster 2000a; Alvik

and Haggren 2003). Intensive workshop production, stimulated directly by growing

demand on the urban markets of northern Europe, resulted in a relatively low cost to the

consumer and the ability to reach a wide spectrum of the population. With its

technologically superior body, which is impervious to liquids, stainless and odour free,

stoneware revolutionized so many domestic activities from washing up to preserving food.

In addition, its increasingly varied repertoire of forms over the fourteenth to fifteenth

centuries reflects a market response to the multiple drinking, decanting, transport, storage

and sanitary needs of town dwellers across the continent. Despite the plain, utilitarian

body, stoneware captured a niche in the popular tableware market of northern Europe,

enabling the aspiring middle classes to imitate aristocratic drinking and dining practices in a

less expensive medium. Stoneware producers substituted fine metalware and drinking glass

with a finely potted ceramic body that imitated their form, function and social role

(Gaimster 1997: ch. 4.4). Given its wide penetration of the international pottery market,

German stoneware may be regarded as a type-fossil of mercantile or 'Hanseatic' urban

culture, which linked consumers irrespectiveof means from London to Tallinn and beyond.

The finds from the castle harbour at Kalmar in southern Sweden provide a snapshot of

the dominance of the trade in German stoneware during the late medieval period. The fact

that stonewares make up around 5 per cent of the overall domestic ceramic assemblage

from the town may be explained by the relatively high numbers of alien names recorded as

resident in the city (Elfwendahl and Gaimster 1995). During the late fourteenth century,

for instance, one-third out of a total of 2000 family names listed as resident in the city were

German in origin. A similar explanation could also be made for the Stockholm stoneware

sequence. Here the well-documented population of resident German merchants provides a

context for the high frequency of imported stonewares recorded in the Gamla Stan (Old

Town) and in neighbouring districts (Gaimster 2002) (Plate 2).

While finds of highly decorated stonewares, such as the distinctive group from the

Lausitz in Saxony, with their ecclesiastical forms, anthropomorphic plastic ornament and

applied gold foil, are found across the Baltic region in urban patrician contexts, as well as

on castle sites and monastic houses (Stephan and Gaimster 2002), urban excavation has

also demonstrated the extent to which undecorated stoneware vessels were afforded almost

disproportionate value by expatriate communities trading on the edge of Europe.

Excavations on St James' Street in the Livonian frontier town of Tartu, Estonia, have

produced a standard fifteenth-century Siegburg beaker inside a moulded leather

cover, which was incised with an ornate frieze of forest animals and birds (Gaimster

1999b: fig. 2).

The subsequent phase of the urban pottery market in the Baltic is defined by a profound

shift in the balance of utilitarian and social roles performed by imported ceramic products.

Increasingly, from the end of the fifteenth century onwards, polychrome-painted tin-

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

416 David Gaimster

Plate 2 Stonewarejugs and beakersfrom Stockholm,Sweden.Type-fossilsof Hanseaticurban

culturein the Baltic.StockholmMedievalMuseum.

glazed earthenware (maiolica) from southern and western Europe, together with stoneware

and earthenware stove-tiles, both transformed by the development of moulded relief

decoration, injected a new luxury element into the Baltic urban household. The

archaeological distribution of polychrome-painted maiolica vessels, in particular, on

Baltic urban and castle sites provides a measure of the critical role of the Hanseatic trading

network in mediating the arrival of Mediterranean Renaissance culture in the north (Falk

and Gaimster 2002). Excavations in major mercantile centres such as Elblag on the Polish

Pomeranian coast and Stockholm, Kalmar, Malmo and Lund in Sweden have produced

the most substantial groups of these exotic imports, which arrived via the Hansa trade

with Antwerp and Bruges. Comparative quantitative analysis of castle finds in the

hinterland of the towns clearly shows that the urban mercantile communities played a

leading role in setting domestic taste in the region.

The archaeological evidence for the spread of the smokeless ceramic tile-stove into the

Baltic forms a further quantitative and qualitative measure of long-distance technological

and cultural transfer from continental Europe. Stove-tile finds make up just under 20 per

cent of all domestic ceramics found on urban mercantile and residential feudal sites across

the region and, as such, represent a key element in the Hanseatic domestic inventory

(Gaimster 1999b, 2001a). As in the case of German stoneware, lead-glazed earthenware

stoves contributed to a technological transformation of the domestic environment. In

addition, with the development from the mid-fifteenth century onwards of coloured glazes

and moulded relief, and with the growing influence of cheap printed propaganda from the

early sixteenth century onwards, they introduced a new iconographic element into the

Baltic domestic scene.

Earthenware stove-tiles, in contrast to stoneware, were a fragile product and risky to

transport over long distances. Although it is possible to identify rare instances of tiles

imported into southern Scandinavia, it is clear from the number and distribution of

production sites and from analysis of the fabrics that most stoves operating in Baltic urban

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 417

households were manufactured locally, often with the use of moulds imported from

northern and central Germany. Production on this scale can only be explained by the

movement of specialist craftsmen or even workshops around and across the Baltic rim.

The combined documentary and archaeological evidence for German tile-makers settling

in Lund, Malmo, Kalmar, Stockholm and Turku from the mid-sixteenth century onwards

illustrates the extent to which specialist continental craftsmen were attracted by the

prospect of new markets opening up in the north (Gaimster 1998: 177, 1999b: 58).

The development of cheap wood-block printing from the late fifteenth century formed

the key factor in the symbolic transformation of domestic ceramics in Germany during the

early years of the Lutheran Reformation. The fusion of graphical reproduction and

moulded technology enabled producers of stoneware vessels and earthenware stoves to

respond immediately to rapidly changing political and religious loyalties in the

development of a new iconographic repertoire over the course of the sixteenth century.

Tiles moulded with woodcut-based representations of the leading protagonists of the

Lutheran Reformation have a particularly widespread archaeological distribution in the

region (Plate 3), the secular personality cults suiting the new confessional and political

affiliations of the Baltic mercantile communities (Gaimster 2001a: 167-68). Out on the

Hansa's western orbit, the City of London has also produced a parallel series of tiles

(Gaimster 2000b: 145-6, 2003: 132-3). These finds place the English metropolis squarely

Plate 3 Redwarestove-tilefrom Turku, Finland,mouldedwith a portraitof Johann Friedrich,

Electorof Saxony,leaderof the SchmalkaldicLeagueof Protestantprinces(c. 1530-47).Photograph

by KirsiMajantie.CopyrightTurkuProvincialMuseum.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

418 David Gaimster

within the Hanseatic cultural network, which was so instrumental in spreading

Protestantism beyond its area of origin in northern Germany.

In contrast to the immediate pre-Reformation phase in the Baltic zone, in which elite

residential sites, such as castles and monasteries, dominate the archaeological distribution

of representational stoves, the new secularized products (particularly those displaying

Lutheran affiliations) appear with greater frequency in urban contexts. This new, socially

inclusive, pattern suggests a radical shift in consumption by which urban mercantile

communities are taking the lead. The emerging archaeological distribution coincides

geographically and socially with the spread of new confessional loyalties across the region.

Cultural transfer and resistance

Imported western ceramics fulfilled dual utilitarian and social roles among the medieval to

early modern mercantile communities living in the Baltic Sea region. Their archaeological

distributions form a signature of Hanseatic cultural codes and lifestyle practices among

dispersed and heterogeneous communities, notably in the spheres of dining culture and

domestic comfort.

By contrast, in the case of Novgorod, out on the north-eastern frontier of the Hanseatic

cultural zone, the archaeological distribution pattern appears atypical. This principal

Hanseatic trading station (Kontor) situated at the northern end of the Baltic-Black Sea

and Baltic-Caspian trade routes, supported two substantial European mercantile

communities during the late Middle Ages: the Gotlander's Court or Gotenhof, founded

by the early twelfth century, and the Court of St Peter, or St Peterhof, the German trading

enclave firmly established by 1191. Both settlements clustered close to the wharves of the

river Volkhov on the market side of the city. The primary purpose of these trading stations

was to exploit the rich forest wilderness of northern Russia and Karelia for pelts, pine

resin (for distilling into pitch) and honey. In return, the city of Novgorod consumed vital

raw materials such as amber and silver from the Baltic and finished goods from western

Europe, including cloth and metal utensils, together with foodstuffs and preservatives,

including herring and salt (Brisbane and Gaimster 2001).

Here the polarized distribution of western ceramic imports around the alien residential

areas of the city contrasts with the pattern recorded in other Baltic trading centres, notably

in the neighbouring Livonian-Russian border city of Pskov where western imports were

dispersed more widely around the settlement (Gaimster 2001b: cf. figs 7, 8). Evidently in

Novgorod, with its strong domestic wood culture, there was entrenched resistance to the

use of ceramic tableware from the west.

Although technically superior, imported stonewares, together with the more decorative

red earthenwares, were generally rejected by the native population in favour of

autochthonous wooden drinking vessels. It looks as if the German ceramics found in

Novgorod were merely part of the domestic toolkit required by Hanseatic traders resident

in the city. Here, on the edge of the pine forest zone, pottery (in this case reduced grey

earthenware) was largely relegated to the utilitarian functions of cooking and food

preparation while wood, with its suitability for lathe-turned, carved and painted surface

decoration, was more suited to table use. This preference for wood at the expense of

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 419

ceramics for dining, therefore, is not just a functional, but a cultural equation (Hather

2001). This conclusion reveals a strongly embedded resistance among the majority of the

native population to alien social practices. The asymmetricalimported pottery distribution

visible in Novgorod contrasts starkly with the picture from contemporary Hanseatic

Kontorsites such as London or Bruges, where Rhenish stoneware imports are found across

the urban landscape, irrespective of social or functional topography. In Novgorod, on the

edge of the forest zone and behind the Catholic-Orthodox frontier of northern Europe,

both alien mercantile and native host communities were keen to express their respective

ethnic identities and cultural loyalties, through their own material culture, including, and

most visibly, in the dining sphere.

Parallel lives: Hansa history and archaeology

Due to the rapid regeneration of town centres on the Baltic littoral, archaeology is

beginning to make a significant impact on the narrative of the Hansa in the popular

histories of northern Europe, its greatest dividend being in the profiling of long-distance

cultural and technological transfers in the domestic sphere. The success of western

European domestic ceramics across the region, and in a range of social contexts, hints at

something more than commercial transactions and the transfer of technical expertise.

With the exception of Novgorod, the relatively homologous pattern of ceramic

consumption reflects a brand loyalty element and a degree of embedded cultural

motivations in the dining sphere and in heating arrangements, which characterize the

Hanseatic mercantile household on the Baltic rim. In a phrase, the material evidence

points to a proto-colonial scenario, comparable to early European contact sites in North

America and the Caribbean where settlers asserted their cultural affiliations, ethnicity,

class and religion through the active use of imported domestic goods and the transfer of

craft production to new markets. Here archaeology has also revealed how indigenous

and African-American populations resisted the colonial order through the active use of

material culture. The colonoware pottery of the coastal south-eastern USA provides a

telling example of allegiance to African foodways among colonial slave populations

(Wheaten 2002).

This quantitative and qualitative profiling of urban ceramic sequences around the

Baltic rim could be applied to Hanseatic trading centres beyond the region, such as to

London or Bruges. At its City base, the Steelyard, London, hosted one of the permanent

trading posts or Kontore of the Hanseatic League. Together with Bergen and Bruges, the

English metropolis formed a nodal point of the Hanseatic commercial network in the

North Sea. Excavations on the site of the Steelyard complex during 1988-9 by the

Museum of London investigated deposits left intact by the development of Cannon

Street Station in the mid-nineteenth century. Masonry walls surviving to a height of

1.4m above the level of the floor running north-south to the river were identified as the

single-aisle Guildhall of the Cologne merchants, who are documented as resident in the

area from c. 1175 (Keene 1989). The 156 moulded stones recovered from the site

belonged to the largest stone building in the metropolis, outside military and

ecclesiastical functions. Detailed analysis of the domestic finds assemblages - work still

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

420 David Gaimster

to be commissioned by the Museum of London - should in due course be able to expose

the degree to which the lifestyles, living conditions and affiliations of the Steelyard

residents were influenced by continental German culture. In addition, targeted analysis

of contemporary waste assemblages associated with documented alien or 'stranger'

communities in London, Southwark and Norwich (cf. Bolton 1998 for London

communities) and their indigenous neighbours may also indicate whether the Baltic

signatures of acculturation and resistance can be extended to the opposite corner of the

Hansa's international trade network.

With its potential for unlocking the cultural dimension at various social levels, on

both the pan-regional and the narrow intramural micro-scale, archaeology is on the

brink of creating a parallel biography of the medieval trading community in northern

Europe, one that that avoids tautology through its use of separate source materials and

sheds a new perspective on the existing economic and commercial data. That said, the

challenge for developing a dynamic and distinctive methodology for urban historical

archaeology in Baltic and North Sea Europe, along the lines suggested by Anders

Andren (1997: 179-83), is to maintain this complementary strategic approach within the

everyday, developer-led rescue environment. If this can be achieved, the developing

material definition of Hanseatic lifestyles offers ample opportunities for cross-referencing

artefacts and texts.

Society of Antiquariesof London

E-mail: dgaimster@sal.org.uk;website: www.sal.org.uk

References

Ahola, M., Hyvonen, A., Pihlman, A. Puhakka, M. and Willner-Ronnholm, M. (eds) 2004. Got

Woldes: Life in Hanseatic Turku.Turku: Turku Provincial Museum.

Alvik, R. and Haggren, G. 2003. Keskiakainen haaksirikkopaikka Nauvon ulkossaristossa. Suomen

keskiajan arkeologian seura {FinnishMedieval Archaeology Society), 2: 18-27.

Andren, A. 1997. Between Artifacts and Texts: Historical Archaeology in Global Perspective. New

York and London: Plenum.

Bolton, J. L. (ed.) 1998. The Alien Communitiesof London in the Fifteenth Century:The SubsidyRolls

of 1440 and 1483-4. Richard III and Yorkist History Trust. Stamford: Paul Watkins.

Bracker, J. (ed.) 1989. Die Hanse: Lebenswirklichkeit und Mythos. Hamburg: Museum fur

Hamburgische Geschichte.

Brisbane, M. and Gaimster, D. 2001. Preface. In Novgorod: The Archaeology of the Russian Medieval

City and its Hinterland (eds M. Brisbane and D. Gaimster). London: British Museum Occasional

Paper 141, pp. vii-ix.

Cieslak, E. and Biernat, C. 1988. History of Gdansk. Gdansk: Wydawnnictwo Morskie.

Elfwendahl, M. and Gaimster, D. 1995. 1 Dagmar Sellings fotspar - en ny granskning av keramiken

fran Slottsfjarden i Kalmar. Kalmar Ian 1995, 80: 95-100.

Evans, D. 2004. Review of Llibecker Kolloquium zur Stadtarchaologie im Hanseraum, vols I- III.

Medieval Archaeology, 48: 354-7.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 421

Falk, A. and Gaimster, D. 2002. Maiolica in the Baltic c. 1350-1 650: a material index of Hanseatic

trade and cultural exchange. In Majolica en glas: van Italie naar Antwerpenen verder:De overdracht

van technologie in de 16de- begin 17de eeuw (ed. J. Veeckman). Antwerp: Stad Antwerpen afdeling

archeologie, pp. 371-90.

Gaimster, D. 1993. Cross-Channel ceramic trade in the late Middle Ages: archaeological evidence for

the spread of Hanseatic culture to Britain. In Archdologie des Mittelalters und Bauforschung im

Hanseraum:Eine Festschriftfur GiinterFehring (ed. M. Glaser). Rostock: Konrad Reich Verlag, pp.

251-60.

Gaimster, D. 1997. German Stoneware 1200-1900. In Archaeology and Cultural History. London:

British Museum.

Gaimster, D. 1998. Den keramiska vittnesborden: Europeisk kulturpaverkan i Lund 1200-1600. In

Metropolis Daniae: Ett styeke Europa (ed. C. Wahloo). Kulturensdrsbok 1998, pp. 159-83.

Gaimster, D. 1999a. The Baltic ceramic market c. 1200-1 600: an archaeology of the Hansa.

FennoscandiaArchaeologica, 16: 59-69.

Gaimster, D. 1999b. German stoneware and stove-tiles: type-fossils of Hanseatic culture in the Baltic

c. 1200-1600. In The Medieval Town in the Baltic: Hanseatic History and Archaeology, Proceedings

of the First & Second Seminar, Tartu, Estonia, 6-7 June 1997 and 26-27 June 1998 (eds R. Vissak

and A. Maesalu). Tartu, Estonia: Tartu City Museum, pp. 53-64.

Gaimster, D. 1999c. Der Keramikmarkt in Ostseeraum 1200-1600: Exportkeramik als Indikator fur

Fernhandelsbeziehungenund die Wanderung des Hansischen Handwerks und der Wohnkultur. In

Lubecker Kolloquium zur Stadtarchdologie in Hanseraum II: Der Handel. Lubeck: Bereich

Archaologie der Hansestadt Liibeck, pp. 99-110.

Gaimster, D. 2000a. Hanseatic trade and cultural exchange in the Baltic c. 1200-1600: pottery from

wrecks and harbours. In Schutz des Kulturerbes unter Wasser, Beitrage zum Internationalen

Kongress fur Unterwasserarchaologie (IKUWA '99), Sassnitz auf Riigen (ed. H. von Schmettow,

A.M. Koldeweij and J.R. ter Molen). Liibstorf, pp. 237-47.

Gaimster, D. 2000b. Saints and sinners: the iconography of imported ceramic stove-tiles in late

medieval and Renaissance London. In Gevonden Voorwerpen:Lost and Found: Essays on Medieval

Archaeologyfor H. J. E. Van Beuningen (eds D. Kicken, A. M. Koldeweij and J. R. ter Molen).

Rotterdam: Rotterdam Papers 11, pp. 142-50.

Gaimster, D. 2001a. Handel und Produktion von Ofenkacheln im Ostseegebiet von 1450 bis 1600:

ein kurzer Uberblick. In Von der Feuerstelle zum Kachelofen - Heizanlagen und Ofenkeramikvom

Mittelalter bis zur Neuzeit, Beitrage des 3. Wissenschaftlicher {Colloquiums Stralsund 9.11.

Dezember 1999, Stralsunder Beitrage zur Archaologie, Kunst und Volkskunde in Vorpommern,

Bd. Ill (eds C. Hoffmann and M. Schneider). Stralsund: Kulturhistorisches Museum,

pp. 165-78.

Gaimster, D. 2001b. Pelts, pitch and pottery: the archaeology of Hanseatic trade in medieval

Novgorod. In Novgorod: The Archaeology of the Russian Medieval City and its Hinterland (eds M.

Brisbane and D. Gaimster). London: British Museum Occasional Paper 141, pp. 67-78.

Gaimster, D. 2002. Keramik i Stockholm 1250-1600: Inflytande fran Hansans handel, kultur och

teknik. In Upptaget: Arkeologi i Stockholm, Sankt Eriks Arsbok 2002 (ed. B. Hallerdt). Stockholm,

pp. 193-215.

Gaimster, D. 2003. Pots, prints and propaganda: changing mentalities in the domestic sphere 1480-

1580. In The Archaeology of Reformation1480-1580 (eds D. Gaimster and R. Gilchrist). Society for

Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 1. Leeds: Maney Publishing, pp. 122-44.

Hackmann, J. 1996. Not only 'Hansa': image of history in the Baltic Sea region. In Die Hanse in

Geschichte und Gegenwart - Konigsberg/Kaliningrad. Mare Balticum 1996. Lubeck-Traverminde:

Ostsee-Akademie, pp. 23-35.

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

422 David Gaimster

Hallerdt, B. (ed.) 2002. Upptaget: Arkeologi i Stockholm, Sankt Eriks Arsbok 2002. Stockholm:

Samfundet S:t Erik/Stockholms Stadsmuseum/Stockholms Medeltidsmuseum.

Hasse, M. 1979. Neues Hausgerat, neue Kleider - eine Betrachtung der stadtischen Kultur im 13.

und 14: Jahrhundert sowie ein Katalog der metallenen Hausgerate. Zeitschriftfur Archdologie des

Mittelalters, 7: 7-83.

Hather, J. 2001. Wood turning technology in medieval Novgorod. In Novgorod: The Archaeology of

the Russian Medieval City and its Hinterland (eds M. Brisbane and D. Gaimster). London: British

Museum Occasional Paper 141, pp. 91-106.

Keene, D. 1989. New discoveries at the Hanseatic Steelyard in London. Hansische Geschichtsbldtter,

107: 15-25.

Jaacks, G. 1989. Warenzug hansischer Kaufleute. In Die Hanse: Lebenswirklichkeitund Mythos II

(ed. J. Bracker). Hamburg: Museum fur Hamburgische Geschichte, cat. 24.63, pp. 622-3.

Lange, H. 2001. Stationen der Geschichte des Konigsberger Schlosses bis zu seiner Sprengung in den

Jahren 1965 bis 1968. Burgen und Schlosser, 3: 154-61.

LubeckerKolloquiumsbdnder , 1997-2004. LubeckerKolloquiumzur Stadtarchdologiein HanseraumI-

IV. Lu'beck:Bereich Archdologie der Hansestadt Lu'beck.

Lubocka-Hoffmann, M. 1997. Retrowersja Starego Maiasta w Elblagu. ArchaeologiaElbingensis,2:

105-19.

Mall, J. and Russow, E. 2003. A study in Bolshevik archaeology - the excavations in Tallinn's town

hall square in 1953. In Travelling with an Archaeologist through the Baltic Countries: Studies in

Honour of Ju'riSelirand. Tallinn/Tartu: Arheoloogiga Laanemeremaades, pp. 173-200.

Schafer, H. 1997. Zur Keramik des 13. und 15: Jahrhunderts in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. In

Bodendenkmalpflegein Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.Jahrbuch 1996-44, pp. 297-335.

Schildhauer, J. 1985. The Hansa: History and Culture. Leipzig: Edition Leipzig.

Stephan, H.-G. 1996. Deutsche Keramik im Handelsraum der Hanse. In Nahrung und Tischkulturim

Hanseraum(eds I. G. Wiegelmann and R.-E. Mohrmann). Minister and New York: Waxmann, pp.

95-123.

Stephan, H.-G. and Gaimster, D. 2002. Die 'Falke-Gruppe': Das reich verzierte Lausitzer Steinzeug

der Gotik und sein archaologisch-historisches Umfeld. Zeitschriftfur Archdologie des Mittelalters,

30: 107-63.

Verhaeghe, F. 1998. Medieval and later social networks: the contribution of archaeology. In Die

Vielfalt der Dinge: Neue Wege zur Analyse mittelalterlicher Sachkultur. Internationaler Kongress

Krems an der Donau Oktober 1997 (ed. H. Hunsdsbichler et al). Vienna: Forschungen des Instituts

fur Realienkunde des Mittelalters und der Friihen Neuzeit, pp. 263-312.

von Bonsdorff, J. 1993. Kunstproduktionund Kunstvervbreitungim Ostseeraumdes Spdtmittelalters.

Helskinki/Helsingfors: Finsk Fornminnesforeningens Tisdkrift, 99.

Wahloo, C. (ed.) 1998. Metropolis Daniae: Ett styeke Europa. Kulturens arsbok 1998. Lund:

Kulturhistoriska Foreningen for Sodra Sverige.

Wheaten, T. R. 2002. Colonoware pottery. In Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology (ed. C. E.

Orser). London and New York: Routledge, pp. 116-18.

Zaske, N. and Zaske, R. 1986. Kunst in Hansestddten. Cologne: Bohlau Verlag.

Dr David Gaimster, formerly Assistant Keeper in the Department of Medieval and Later

Antiquities at the British Museum, London (1986-2001) and Senior Policy Advisor in the

Cultural Property Unit at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2002-4), is now

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A parallel history 423

General Secretary and Chief Executive of the Society of Antiquaries of London (since

2004).

This content downloaded from 200.16.86.36 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 10:57:15 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Barroco Como Concepto Básico Del Arte - Ernest C. HassoldDocument29 pagesBarroco Como Concepto Básico Del Arte - Ernest C. Hassolddailearon3110No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Piracy On Baltic - DAVID K. BJORKDocument31 pagesPiracy On Baltic - DAVID K. BJORKdailearon3110No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Patronazgo de Bernini X Cristina de Suecia - Lilian H. ZirpoloDocument7 pagesPatronazgo de Bernini X Cristina de Suecia - Lilian H. Zirpolodailearon3110No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Argentines of To-Day V1Document804 pagesArgentines of To-Day V1dailearon3110No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- MTH103 Notes Lec1Document5 pagesMTH103 Notes Lec1stanleyNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Forex Operations: Prof S P GargDocument25 pagesForex Operations: Prof S P GargProf S P Garg100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Eureka ForbesDocument21 pagesEureka ForbesLalitNo ratings yet

- Africa CNDocument157 pagesAfrica CNDavid LuNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Tata Motors Finance Limited (Formerly Known As Sheba Properties LTD) Cardex I (Contract Details)Document16 pagesTata Motors Finance Limited (Formerly Known As Sheba Properties LTD) Cardex I (Contract Details)Vivek MohanNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- ST JohnDocument58 pagesST JohnAashay KulshresthaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Global Interstate SystemDocument1 pageGlobal Interstate SystemDiana CamachoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Dokumen EksporDocument4 pagesDokumen EksporDicky AditiyaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Be 313 - Week 4-5 - Unit Learning BDocument25 pagesBe 313 - Week 4-5 - Unit Learning Bmhel cabigonNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Notes 2Document14 pagesMacroeconomics Notes 2Maria GarciaNo ratings yet

- JRK Lussama Cikri TNRK Rou Rnterüof RV Prpvo DießenDocument2 pagesJRK Lussama Cikri TNRK Rou Rnterüof RV Prpvo DießenossNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Economic AnalysisDocument36 pagesEconomic AnalysisMilkessa SeyoumNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Marketing 13Document15 pagesMarketing 13mercycheptoo2015No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Konsep Capital Budgeting - TurkiDocument20 pagesKonsep Capital Budgeting - TurkiyayaNo ratings yet

- Micro Chap6 Acts Draft FinishedDocument5 pagesMicro Chap6 Acts Draft FinishedBhebz Erin MaeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 International Trade PlanswtoDocument11 pagesChapter 2 International Trade PlanswtoLee TeukNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Ch-3 IMDocument9 pagesCh-3 IMJohnny KinfeNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Collecting Branch: Servicing Branch:: Eps1 LIC of India, JammalamaduguDocument2 pagesCollecting Branch: Servicing Branch:: Eps1 LIC of India, JammalamadugujayanthkalkatteNo ratings yet

- LU1 - Revenue and Receipts CycleDocument17 pagesLU1 - Revenue and Receipts CycleNqubekoNo ratings yet

- Cobined PDF - Zonewise Supermarkets With Home DeliveryDocument8 pagesCobined PDF - Zonewise Supermarkets With Home DeliveryVidya PintoNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Currency Dealing and Exchange Rate QuotationsDocument6 pagesMechanics of Currency Dealing and Exchange Rate Quotationsvijayadarshini vNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Document1 pageTax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Karthik ANo ratings yet

- LNG Daily - 30092021Document21 pagesLNG Daily - 30092021Đức Vũ NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Financial Management MCQ MergedDocument59 pagesFinancial Management MCQ Mergedvenkatesh vNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Societe Chinoise LTD: Irrevocable Corporate Purchase OrderDocument4 pagesSociete Chinoise LTD: Irrevocable Corporate Purchase OrderPatrick NoelNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Rice Exports From Myanmar To West AfricaDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Rice Exports From Myanmar To West AfricaSu Wai MyoNo ratings yet

- Botbro NewDocument47 pagesBotbro NewpritisainirNo ratings yet

- MGVCL New Application Payment ReceiptDocument1 pageMGVCL New Application Payment ReceiptnysadebtmanagementNo ratings yet

- Invoice - HeadsetDocument1 pageInvoice - Headsetjyotsna jhaNo ratings yet

- 3B Group2 Case StudyDocument8 pages3B Group2 Case Studynatasya hanimNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)