Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 - The Shared Decision Continuum Kon JAMA 2010

1 - The Shared Decision Continuum Kon JAMA 2010

Uploaded by

Carlos GardelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 - The Shared Decision Continuum Kon JAMA 2010

1 - The Shared Decision Continuum Kon JAMA 2010

Uploaded by

Carlos GardelCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

The Shared Decision-Making Continuum

Alexander A. Kon, MD tinuum (FIGURE). At one end is patient- or agent-driven de-

cision making, at the opposite is physician-driven decision

making, and in the middle are many possible approaches.

D

URING THE 20TH CENTURY, MEDICAL DECISION MAK- Discussion of 5 points along the continuum illustrates some

ing shifted from a paternalistic approach to an au- of the possible approaches.

tonomy-based standard in the United States. Now, In patient/agent-driven decision making (akin to strict au-

in the 21st century, the pendulum is swinging tonomy), the physician presents all options and the patient

back and the medical community and the public are in- makes his/her own choice. The physician provides expert

creasingly embracing shared decision making. In many other knowledge only and makes no recommendations.

parts of the world paternalism remained the primary ap- In physician recommendation decision making, the phy-

proach, yet there is now a move toward shared decision mak- sician explains all options and also makes a recommenda-

ing occurring internationally. This “meeting in the middle” tion. Because many decisions in health care are value laden,

has been spurred by the 2004 endorsement of shared deci- physicians must base their recommendations on the pa-

sion making over either strict autonomy or physician- tient’s values rather than on their own. Ascertaining the pa-

directed decision making by the leading critical care orga- tient’s values, however, often requires time and advanced

nizations in Europe and the United States.1 Furthermore, communication skills. Furthermore, when a patients asks

the American Medical Association, the American College the physician what he/she would do, the physician must con-

of Critical Care, and the American Academy of Pediatrics sider the patient’s perspective and ensure that he/she is nei-

all advocate shared decision making.2-4 ther intentionally nor unintentionally coercive.7

Most patients (the term patient in this article denotes either In equal partners decision making, the patient and phy-

the patient or the patient’s agent or surrogate decision maker sician work together to reach a mutual decision. This pro-

in cases of an incompetent patient) and family members pre- cess often requires a longstanding relationship, and both par-

fer shared decision making over either strict autonomy or phy- ties must understand the values and biases of the other.

sician-directed decision making.1,5,6 Recent legislation in US Mutual respect and understanding are essential. Because the

states gives physicians greater control. For instance, the Texas patient and physician necessarily have different perspec-

Advance Directives Act of 1999 (Texas Health & Safety Code tives, the physician must ensure that it is the patient’s val-

§166.046) specifies the process by which physicians can with- ues, not his/her own, that guide decision making.

draw life-sustaining interventions over patient objection, and In some cases it may be appropriate for the physician to

in 2009 California enacted similar legislation (California Pro- bear the major burden of decision making.8 With informed

bate Code §4736). Such studies and legislation demonstrate nondissent decision making, the physician, guided by the

that the move away from a strict autonomy model is now widely patient’s values, determines the best course of action and

accepted in the United States. In Europe and other parts of fully informs the patient. The patient may either remain si-

the world, the move away from paternalism toward shared de- lent, thereby allowing the physician’s decision to stand, or

cision making is also becoming accepted in medical and lay veto the decision. In this approach the patient must under-

communities, and patients are increasingly being given greater stand all pertinent information (as he/she would in any

control over their medical care. method of decision making). Furthermore, the patient must

Although shared decision making is becoming the new appreciate that silence will be construed as tacit agree-

standard, it remains unclear exactly what “shared decision ment. Patients must understand that they are welcome to

making” means. The model for shared decision making de- veto the decision and if so, their wishes will be honored and

scribed herein is consistent with ethical principles and pa- they will receive excellent care.

tient preferences and can be referred to as the “shared de-

Author Affiliations: Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, the Program in

cision-making continuum” because shared decision making Bioethics, and the Clinical and Translational Science Center, University of Califor-

will necessarily take different forms in different situations. nia, Davis.

Corresponding Author: Alexander A. Kon, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Uni-

Shared decision making does not mean the same thing versity of California, Davis, 2516 Stockton Blvd, Sacramento, CA 95817 (aakon

in all cases and therefore can best be understood as a con- @ucdavis.edu).

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, August 25, 2010—Vol 304, No. 8 903

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Universidade de São Paulo User on 03/24/2013

COMMENTARY

sistent with the patient’s preferences and the physician is

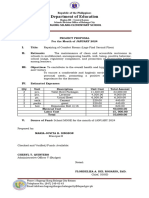

Figure. Shared Decision-Making Continuum

making decisions based on understanding the patient’s val-

ues and assessment of the patient’s best interest. This does

not mean that the physician is obligated to assume the role

n

tio

e

riv

of decision maker. If the physician is uncomfortable in this

riv r

da

en

t-d - o

m ian

-d

is d

nt

en

nd me

e n nt

n

co ic

se

ia

rtn l

s

role, he/she may decline to serve in this capacity.

m

pa ua

ag atie

re hys

no for

er

ic

Eq

ys

In

P

While this approach to decision making has focused on

Ph

the physician-patient dyad, an experienced clinician can in-

100% 0% clude others (eg, family members, friends, allied health pro-

fessionals) in the decision-making team. Expanding from

Patient Physician the dyad to the team approach requires experience and ex-

responsibility responsibility

for decisions for decisions

cellent communication skills. Furthermore, all team mem-

bers should understand the process and goals and appreci-

0% 100% ate the primacy of the patient’s values.

The goal of shared decision making is to make decisions in

a manner consistent with the patient’s wishes. The patient drives

At the other extreme end of the continuum from patient/ the process. Determining where on the shared decision-

agent-driven decision making is physician-driven decision making continuum the patient feels most comfortable re-

making. In general, physicians should independently make quires clear communication and dedicated time. Shared de-

only those decisions that are value-neutral (eg, deciding what cision making is often facilitated by a long-standing relationship

size endotracheal tube to use). Physicians must be ex- between the physician and patient, although such a relation-

tremely careful because patients may have strong feelings ship is not compulsory.10 Active listening skills are essential

about seemingly value-neutral issues. For example, a child so that the physician does not inappropriately take too much

may wish to have an intravenous line placed in the right hand control nor force patients to bear more of the burden than they

because the intensive care unit allows parents to sit only on wish. Future work should assess patient satisfaction with the

the left side of the bed (due to equipment placement) and shared decision-making process.

the patient wishes to have her left hand free to hold her moth- Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Center for Research Re-

er’s hand. Similarly, a patient may prefer a conventional ven- sources grant UL1 RR024146-01.

tilation mode even when high-frequency ventilation could Role of the Sponsors: The funding agency did not participate in the preparation,

review, or approval of the manuscript.

provide greater lung protection because conventional ven-

tilation requires less sedation, and being able to interact with REFERENCES

family members is paramount. As such, when making what

1. Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU.

appear to be value-neutral decisions physicians should be Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brus-

aware of possible patient preferences and include patients sels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(5):770-784.

2. American Medical Association. Policy D-373.999 Informed Patient Choice and

in decision making whenever appropriate. Shared Decision Making. https://ssl3.ama-assn.org/apps/ecomm/PolicyFinderForm

Patient preferences must guide the approach used, and .pl?site=www.ama-assn.org&uri=/ama1/pub/upload/mm/PolicyFinder/policyfiles

/DIR/D-373.999.HTM. Accessed July 30, 2010.

physicians must appreciate that each patient is different and 3. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al; American College of Critical Care

may have different preferences at different times and for dif- Medicine Task Force 2004-2005, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical prac-

ferent types of decisions. Some physicians may tend to use tice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit:

American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med.

only certain decision-making approaches for specific types 2007;35(2):605-622.

of decisions; however, patient preferences for decision- 4. Mercurio MR, Adam MB, Forman EN, Ladd RE, Ross LF, Silber TJ; American

Academy of Pediatrics Section on Bioethics. American Academy of Pediatrics policy

making approaches vary widely regardless of the type of de- statements on bioethics: summaries and commentaries: part 1. Pediatr Rev. 2008;

cision being considered. For example, some physicians tend 29(1):e1-e8.

5. Shields CG, Morrow GR, Griggs J, et al. Decision-making role preferences of

to use the patient/agent-directed approach for end-of-life de- patients receiving adjuvant cancer treatment. Support Cancer Ther. 2004;1

cisions; however, even in end-of-life decision making when (2):119-126.

6. Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B. Clinical decision-making: Patients’ pref-

decisions require value judgments, many patients simply erences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):189-196.

want the physician to decide.9,10 The types of decisions that 7. Kon AA. Answering the question: “Doctor, if this were your child, what would

call for different approaches cannot be categorized because you do?” Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):393-397.

8. Kon AA. The “window of opportunity”: helping parents make the most diffi-

each patient is different and it is the patient, not the deci- cult decision they will ever face using an informed non-dissent model. Am J Bioeth.

sion under consideration, that guides the process. 2009;9(4):55-56.

9. Johnson MF, Lin M, Mangalik S, Murphy DJ, Kramer AM. Patients’ percep-

Particularly in end-of-life decision making, some physi- tions of physicians’ recommendations for comfort care differ by patient age and

cians may be uncomfortable allowing patients to abdicate gender. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(4):248-255.

10. Mazur DJ, Hickam DH, Mazur MD, Mazur MD. The role of doctor’s opinion

decisional authority. However, there is no ethical reason to in shared decision making: what does shared decision making really mean when

disallow this form of decision making when doing so is con- considering invasive medical procedures? Health Expect. 2005;8(2):97-102.

904 JAMA, August 25, 2010—Vol 304, No. 8 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Universidade de São Paulo User on 03/24/2013

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Case Study - Metabical - Pricing, Packaging and Demand Forecasting For A New Wight-Loss DrugDocument3 pagesCase Study - Metabical - Pricing, Packaging and Demand Forecasting For A New Wight-Loss DrugSallySakhvadzeNo ratings yet

- 5402622-1EN Rev 01 9900 Installation ProcedureDocument64 pages5402622-1EN Rev 01 9900 Installation ProcedureJonathan Woodward100% (1)

- Veterinary Necropsy TechniqueDocument5 pagesVeterinary Necropsy Techniquenateriver44No ratings yet

- DIASS Lesson 6Document34 pagesDIASS Lesson 6PBCSSI Ma'am MarizNo ratings yet

- DIAS Week 5a - Career Opportunities of Counsellor - Responsibilities of CounsellorsDocument3 pagesDIAS Week 5a - Career Opportunities of Counsellor - Responsibilities of CounsellorsRoxanne Gensaya0% (1)

- Tetagam P: Human Tetanus Immunoglobulin IM 250 IUDocument25 pagesTetagam P: Human Tetanus Immunoglobulin IM 250 IUhamilton lowisNo ratings yet

- Multicultural in Counseling - 1Document11 pagesMulticultural in Counseling - 1sarahariffin001No ratings yet

- Diass Second Periodical TestDocument6 pagesDiass Second Periodical TestMiyu Viana100% (2)

- Keerai BenefitsDocument3 pagesKeerai BenefitsjnaguNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: Students and Anxiety Piña 1Document6 pagesLiterature Review: Students and Anxiety Piña 1api-534522249No ratings yet

- Heal My Heart: Stories of Hurt and Healing From Group TherapyDocument15 pagesHeal My Heart: Stories of Hurt and Healing From Group Therapyshinta septiaNo ratings yet

- Repair Proposal-CrDocument2 pagesRepair Proposal-CrAriel PunzalanNo ratings yet

- HRBA Badac LECTUREDocument35 pagesHRBA Badac LECTUREBluboyNo ratings yet

- Fdar Lp6 MontemayorDocument5 pagesFdar Lp6 MontemayorEden Marie MangaserNo ratings yet

- Room Pressurization Control Application GuideDocument6 pagesRoom Pressurization Control Application Guidemohamed adelNo ratings yet

- Hospital Administration Unit 2Document2 pagesHospital Administration Unit 2Alya AdeliaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 2 AnswersDocument4 pagesModule 1 2 AnswersGlezy GeligNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Counselling ProfessionDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Counselling ProfessionnisdanawiNo ratings yet

- Fusion AP Manual 309550YDocument46 pagesFusion AP Manual 309550YDaniel RondónNo ratings yet

- Social Work and Spirituality (Transforming Social Work Practice)Document161 pagesSocial Work and Spirituality (Transforming Social Work Practice)Grace Chelle Ocba100% (2)

- ESMO 2022 EGFR Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer 20Document1 pageESMO 2022 EGFR Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer 20EDWIN WIJAYANo ratings yet

- Las 7 First QuarterDocument3 pagesLas 7 First QuarterKirby FuentesNo ratings yet

- Provisional Time Table - IPPL 2023 - MS As On 10-08-2023Document2 pagesProvisional Time Table - IPPL 2023 - MS As On 10-08-2023Kahah gdaubNo ratings yet

- TFN 2Document37 pagesTFN 2Tracy DavidNo ratings yet

- THC 104 - Unit 3 2nd Sem 1Document29 pagesTHC 104 - Unit 3 2nd Sem 1Sharlyne PimentelNo ratings yet

- 261-Article Text-575-1-10-20180915Document11 pages261-Article Text-575-1-10-20180915hector michel galindo hernandezNo ratings yet

- RNTCPDocument43 pagesRNTCPSanket AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Pre Marital SexDocument4 pagesSynthesis Pre Marital SexMajoy Britania SalazarNo ratings yet

- #RD qUARTER LEAST LEARNED SKILLSDocument1 page#RD qUARTER LEAST LEARNED SKILLSIrene CatubigNo ratings yet

- Design Documentation L4Document27 pagesDesign Documentation L4KOFI BROWNNo ratings yet