Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shree Ram Mills LTD Vs Utility Premises P LTD 2103S070325COM254171

Uploaded by

Aman Bajaj0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views9 pages1. The Supreme Court of India heard an appeal regarding an order by the Bombay High Court appointing arbitrators under Section 11(6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act to resolve a dispute between Shree Ram Mills Ltd. and Utility Premises (P) Ltd.

2. The key issue in the case was whether there was a live dispute left between the parties regarding additional floor space index (FSI) that Shree Ram Mills was obligated to provide, or if the claims were barred by limitation.

3. The case involved a complex factual background regarding multiple agreements between the parties for development of a property, appointment of arbitrators, and subsequent memorandums of understanding and cancell

Original Description:

Original Title

Shree_Ram_Mills_Ltd_vs_Utility_Premises_P_Ltd_2103S070325COM254171

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. The Supreme Court of India heard an appeal regarding an order by the Bombay High Court appointing arbitrators under Section 11(6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act to resolve a dispute between Shree Ram Mills Ltd. and Utility Premises (P) Ltd.

2. The key issue in the case was whether there was a live dispute left between the parties regarding additional floor space index (FSI) that Shree Ram Mills was obligated to provide, or if the claims were barred by limitation.

3. The case involved a complex factual background regarding multiple agreements between the parties for development of a property, appointment of arbitrators, and subsequent memorandums of understanding and cancell

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views9 pagesShree Ram Mills LTD Vs Utility Premises P LTD 2103S070325COM254171

Uploaded by

Aman Bajaj1. The Supreme Court of India heard an appeal regarding an order by the Bombay High Court appointing arbitrators under Section 11(6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act to resolve a dispute between Shree Ram Mills Ltd. and Utility Premises (P) Ltd.

2. The key issue in the case was whether there was a live dispute left between the parties regarding additional floor space index (FSI) that Shree Ram Mills was obligated to provide, or if the claims were barred by limitation.

3. The case involved a complex factual background regarding multiple agreements between the parties for development of a property, appointment of arbitrators, and subsequent memorandums of understanding and cancell

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

MANU/SC/1999/2007

Equivalent Citation: 2008(3)ALT2(SC ), 2007(1)ARBLR517(SC ), 2007 (2) AWC 1848 (SC ), 2007(4)BomC R109, (2007)3C ompLJ200(SC ),

JT2007(4)SC 501, 2009-3-LW833, 2007(2)RC R(C ivil)720, 2007(4)SC ALE571, (2007)4SC C 599, [2007]5SC R279

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

Civil Appeal No. 1523 of 2007 (Arising out of SLP (C) No. 15656 of 2006)

Decided On: 21.03.2007

Appellants: Shree Ram Mills Ltd.

Vs.

Respondent: Utility Premises (P) Ltd.

Hon'ble Judges/Coram:

H.K. Sema and V.S. Sirpurkar, JJ.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Harish Salve and Shyam Divan, Sr. Advs., Saurav

Agrawal, Lalit Kataria, Ruby Singh Ahuja, Debmalya Banerjee and Manik Karanjawala,

Advs

For Respondents/Defendant: K.K. Venugopal and Ranjit Kumar, Sr. Advs., Sushil K.

Tekriwal and Venkateswara Rao Anumolu, Advs.

Case Category:

ARBITRATION MATTERS

JUDGMENT

V.S. Sirpurkar, J.

1. Leave granted.

2 . An order under Section 11(6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

(hereinafter called as "the Act" for short) appointing Arbitrators, passed by the

Designate Judge of the Bombay High Court is questioned in this appeal at the

instance of Shree Ram Mills Ltd. (hereinafter called "the petitioner"). The said order

is assailed mainly on two grounds, firstly, that there was no live issue in existence in

between the parties and the learned Judge erred in holding that there was a live issue

in between the parties and secondly that the claim had become barred by limitation

between the parties. As against this the respondents M/s. Utility Premises (P) Ltd.,

supported the order and pointed out that in pursuance of the order passed not only

had the Arbitrator been appointed but they had also chosen the third Arbitrator to

preside over the Arbitral Tribunal and the Arbitral Tribunal had commenced its

proceedings. Presently the proceedings before the Arbitral Tribunal are stayed. It has,

therefore, to be decided as to whether the order passed under Section 11(6) of the

Act appointing the Arbitrators is good order in law particularly in the wake of the

above two objections.

3. Following undisputed facts would have to be borne in mind before approaching the

questions raised.

The appellant is a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 1956, so also the

05-07-2020 (Page 1 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

respondent. The appellant company became a sick industrial unit sometime in the

year 1987 under the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985

(hereinafter referred to as "the SICA"). It was ordered to be wound up in the year

1994 and on approaching the Board For Industrial and Financial Reconstruction

(BIFR) a rehabilitation scheme was worked out whereby IDBI was appointed as an

operating agency under the scheme. The Asset Sale Committee approved the sale of

1.20 lakh sq.ft. FSI owned by the appellant company to the respondent for a total

sale consideration of Rs. 21.60 crores and accordingly an agreement came to be

executed in between the parties on 27.4.1994. This was a Joint Development

Agreement between the parties in respect of the land owned by the appellant. By

Clause 1 of the agreement, the area mentioned for development was between 86,000

sq.ft to 1.20 lakh sq.ft. Clause 15 of the said agreement provides that the land

owner, the appellant herein, shall not create any encumbrance or third party rights.

By Clause 19 the appellant had undertaken to add additional FSI. By Clause 22 the

period was fixed for utilization of the full FSI covered under the agreement. Clause

24 was the Arbitration Clause to resolve the disputes, if any, between the parties. The

property covered was described in the Third Schedule of the said agreement which

mentions 1. 20 lakh sq.ft. FSI.

4 . After this agreement a second agreement came to be executed in between the

parties on 18.7.1994. This was necessitated because the appellant herein could make

available only 86,725 sq.ft. FSI. Under this second agreement it was agreed to by the

appellant herein that the further land admeasuring 2500 sq.mtrs. would be allowed to

be developed by the respondent. The said 2500 sq.mtrs. land was reserved by

Bombay Municipal Corporation for Municipal Primary School and playground.

However, the appellant herein undertook to shift the said reservation to some other

property of the appellant at the cost of the respondent. There was an arbitration

clause vide Clause No. 10 in this agreement also. On 9.11.1994 there was a Tripartite

Agreement between the appellant and respondent herein along with one Bhupendra

Capital and Finance Limited whereby 50% of the appellant's entire interest under the

Agreement dated 27.4.1994 and 18.7.1994 was agreed to be transferred. On

22.6.1996 the agreement dated 18.7.1994 was cancelled by mutual consent as the

parties were unable to agree on the cost of shifting the reservation which was agreed

to in the agreement dated 18.7.1994. It was, therefore, agreed vide Clause 5 that the

respondent and the third party brought in, i.e., Bhupendra Capital and Finance Ltd.,

would have no right or claim in respect of the said property belonging to the

appellant and more particularly described in the First Schedule, save and except, the

86725 sq.ft. FSI. On 28.6.1996 the respondent herein entered into an Assignment

Agreement with Ansal Housing and Construction to build flats on the area with FSI of

86725 sq.ft. On 4.5.2001 the respondent herein had filed a petition under Section 9

of the Act seeking injunction and appointment of Receiver in respect of 2500 sq.mtrs.

of land. However, that was dismissed by the High Court on the ground that the area

was covered under the agreement dated 18.7.1994 and it was cancelled by an

agreement dated 22.6.1996 and, therefore, the application was not maintainable. The

appeal against this order also failed vide order dated 3.6.2002.

5. On 12.9.2001 respondent and one Santosh Singh Bagla who was the Promoter of

the respondent company, filed application before the Appellate Authority for

Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (AAIFR) contending therein that the promoters

of the petitioner company were guilty of misfeasance and hence those acts were

liable to be inquired into. It was secondly prayed that the Board of Directors of the

appellant company should be superseded. It was thirdly prayed that the injunction be

issued restraining the appellant from selling or transferring the lands. This

05-07-2020 (Page 2 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

application was dismissed by AAIFR leaving the parties to get the disputes

adjudicated before an appropriate forum. It is to be noted here that a specific

statement was made before the AAIFR by the respondent herein that the sale of 1.20

lakh sq.ft. was not the subject matter of the application as the separate proceedings

were being contemplated before the appropriate forum. On 11.6.2002 the respondent

served a notice invoking the arbitration clause under agreements dated 27.4.1994

and 18.7.1994 on the ground that the petitioner had denied its liability to transfer the

FSI beyond 86725 sq.ft. though it was bound to make available FSI of 1.20 lakh

sq.ft. to the respondents.

6 . The respondent and Shri Santosh Singh Bagla filed a writ petition in the Delhi

High Court on 26.7.2004 whereby they challenged the order passed by the AAIFR

dated 12.9.2001. Though the respondents had, in their appeal before AAIFR, claimed

that the sale of 1.20 lakh sq.ft. of FSI was not the subject matter of that application,

it was all the same prayed before the High Court in the writ petition that the appellant

should be restrained from transferring the additional FSI left with them. Thereupon

an undertaking was given by the counsel for the appellant that the appellant would

not sell the property which was covered in the agreement dated 27.4.1994. On

6.8.2004 the appellant agreed to mortgage the property covered by the agreement

dated 27.4.1994 in favour of IL&FS for Rs. 50 crores. On 15.10.2004 the appellant

company was released from SICA as it became viable.

7. At this juncture on 19.1.2005 a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed

between the parties to settle all disputes between them which naturally included the

issue regarding the transfer of 1.20 lakh sq.ft. of FSI. The respondent under the same

agreed to accept 1.20 crores out of which a payment of Rs. 10 lakhs was already

made by the appellant to the respondent. The appellant also agreed to execute the

necessary conveyance deed as per agreement dated 27.4.1994 and 22.6.1996 thereby

seeking to confine the claim of the respondent to 86725 sq.ft. of FSI. This MoU was

cancelled by the respondent on 8.3.2005 and the respondent returned the amount of

Rs. 10 lakhs. The respondent invoked the Arbitration Clause under the Agreements

dated 27.4.1994 and 18.7.1994 by a notice dated 24.5.2005. The said notice was

replied to by the appellant vide its reply dated 21.6.2005 denying its liability and as a

result an Arbitration Petition under Section 11(6) of the Act was filed on 1.7.2005 for

appointing Shri S.C. Agarwal as the Sole Arbitrator. It is this application which was

disposed of by the learned Judge on 11.8.2006 which is the subject matter of the

present proceedings before us at the instance of the appellant. As has been stated

earlier, the learned Senior Counsel Shri Salve basically raised two points, they being

(i) that there was no live issue left in between the parties and controversy had

become dead; and (ii) that the claim, if any, of the respondent had become barred by

limitation. In support of his arguments the learned Counsel painstakingly took us

through the whole record.

8 . Shortly stated the argument of the learned Counsel is that there is no live issue

remaining between the parties particularly in respect of 1.20 lakh sq.ft. of FSI.

Learned Counsel points out firstly that the subject of 1.20 lakh sq.ft. of FSI being

made available under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 was finally given a decent

burial by the parties by the MoU dated 19.1.2005 whereunder the respondent had

specifically agreed to restrict his claim only to 86725 sq.ft. of FSI covered under the

agreement dated 27.4.1994. He points out that in pursuance of that MoU not only did

the respondent accept the draft of Rs. 10 lakhs out of the total agreed amount of Rs.

1.20 crores but also proceeded to encash the same. Learned Counsel points out that

on a second thought the respondent proceeded to cancel the said agreement and

05-07-2020 (Page 3 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

thereupon proceeded to serve an arbitration notice on 24.5.2005. Learned Counsel,

therefore, points out that firstly it cannot be said that respondents had any right

under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 left with it and if at all there were any such

rights, they were crystallized vide the MoU dated 19.1.2005 wherein it had

specifically agreed to give up the rest of the claim barring the claim of 86725 sq.ft.

FSI and the appellant would have no qualms about the claim of 86725 sq.ft. FSI and

it would always be prepared to convey the same in terms of the agreement dated

27.4.1994. Learned counsel argues that having a second thought regarding the MoU

dated 19.1.2005 the respondent cannot be allowed to wriggle out of its liabilities and

fall back upon the agreement dated 27.4.1994 which had become an antiquated

agreement. If at all it has any rights, those rights would be in terms of the MoU dated

19.1.2005. It is, therefore, pointed out that there is no live issue left between the

parties, more particularly in respect of 1.20 lakh sq.ft. FSI out of which 86725 sq.ft.

FSI has already been given in possession of the respondent.

9. Learned Counsel further argues that even if there are any rights left, the claim of

the respondent has become hopelessly barred by time. Learned Counsel contends that

the Arbitral Tribunal would now have to go back to the agreement dated 27.4.1994

and interpret the same to decide the rights between the parties which is not possible

under the law of limitation. The learned Counsel suggests a simple test that a suit for

specific performance of the agreement dated 27.4.1994 would obviously be time

barred and, therefore, the respondent cannot have an arbitration as regards that

agreement. Learned Counsel lastly states that while passing the order under Section

11(6) of the Act, the issues regarding the limitation and the jurisdiction could be left

open to be decided by the Arbitral Tribunal, however, since the learned Designated

Judge has decided those issues, there will be no question of the Arbitral Tribunal

deciding these questions and it is, therefore, that the appellant is required to

challenge the order under Section 11(6) of the Act.

1 0 . Shri Venugopal, the learned Senior Counsel appearing on behalf of the

respondent, however, pointed out that the controversy regarding the liability of the

appellant to make available 1.20 lakh sq.ft. of FSI was never dead as otherwise there

was no question of the respondent executing the MoU as late as on 19.1.2005. He

points out that the appellant had given an undertaking in respect of that property

before the Delhi High Court in a writ petition which writ petition is still pending

before the Delhi High Court and the appellant is facing contempt proceedings on

account of the breach of the undertaking. Learned Counsel further points out that

firstly there was no necessity on the part of the appellant to extend the agreement

dated 27.4.1994 by agreeing to handover the rest of the FSI beyond 86725 sq.ft. by

an agreement dated 18.7.1994. It was only on account of the fact that the appellant

also felt bound by the agreement dated 27.4.1994 to transfer 1.20 lakh sq.ft. FSI

under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 for which he had received full consideration of

Rs. 21.60 crores. Learned Counsel was at pains to point out further that in fact it was

an admitted position that the appellant got approximately Rs. 4 crores more as the

respondent had paid a sum of Rs. 25 crores approximately on behalf of the appellant

company which was its financial liability. Learned Counsel points out that issue

regarding 1.20 lakh sq.ft. FSI was never closed and was always alive between the

parties which prompted the parties ultimately to execute the MoU dated 19.1.2005.

Learned Counsel then points out that the respondent had cancelled the MoU later on

realizing that the entire property stood mortgaged by the appellant on 6.8.2004

which also included the land measuring 4848.10 sq.ft. which was the subject matter

of the agreement dated 27.4.1994. He, therefore, points out that the parties were

continuously negotiating in respect of the liability on the part of the appellant to

05-07-2020 (Page 4 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

transfer 1.20 lakh sq.ft. FSI and there was no resolution of that issue. Learned

Counsel points out that the moment the MoU was cancelled, the parties reverted back

to their rights under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 and, therefore, it cannot be said

that the claim of the respondent stood satisfied. Learned Counsel further points out

that since liabilities under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 were constantly being

negotiated and re-negotiated in so many proceedings, it cannot be said that firstly

the issue between the parties was dead and secondly the application under Section

11(6) was barred by time. Learned Counsel in that behalf relied on the reported

decision of this Court in Hari Shankar Singhania and Ors. v. Gaur Hari Singhania and

Ors. MANU/SC/1686/2006 : AIR2006SC2488 . It was lastly suggested by the learned

Counsel that the issue as to whether there was any live issue or not and the issue of

limitation could be decided by the Arbitral Tribunal under Section 16 of the Act and it

cannot be said that those issues were finally decided by the learned Judge while

passing the order under Section 11(6) of the Act. He points out that it is only for the

purpose of appointing the Arbitrator that the learned Designated Judge has referred

the live issue and the issue of limitation.

11. On these rival contentions it has to be seen as to whether the learned Judge was

right in passing the order.

We shall take up the last contention raised by the appellant regarding the scope of

the order passed by the Chief Justice or his Designate Judge. It was contended that

since the Designate Judge has already given findings regarding the existence of live

claim as also the limitation, it would be for this Court to test the correctness of the

findings. As against this it was argued by the respondent that such issues regarding

the live claim as also the limitation are decided by the Chief Justice or his Designate

not finally but for the purpose of making appointment of the Arbitrators under

Section 11(6) of the Act. In our opinion what the Chief Justice or his Designate does

is to put the arbitration proceedings in motion by appointing an Arbitrator and it is

for that purpose that the finding is given in respect of the existence of the

arbitration clause, the territorial jurisdiction, live issue and the limitation. It cannot

be disputed that unless there is a finding given on these issues, there would be no

question of proceeding with the arbitration. Shri Salve as well as Shri Venugopal

invited our attention to the observations made in para 39 in SBP & CO. v. Patel

Engineering Ltd. and Anr. MANU/SC/1787/2005 : AIR2006SC450 which are as

under:

It is necessary to define what exactly the Chief Justice, approached with an

application under Section11(6) of the Act, is to decide at that stage.

Obviously, he has to decide his own jurisdiction in the sense whether the

party making the motion has approached the right High Court. He has to

decide whether there is an arbitration agreement, as defined in the Act and

whether the person who has made the request before him, is a party to such

an agreement. It is necessary to indicate that he can also decide the question

whether the claim was a dead one; or a long- barred claim that was sought

to be resurrected and whether the parties have concluded the transaction by

recording satisfaction of their mutual rights and obligations or by receiving

the final payment without objection. It may not be possible at that stage, to

decide whether a live claim made, is one which comes within the purview of

the arbitration clause. It will be appropriate to leave that question to be

decided by the Arbitral Tribunal on taking evidence, along with the merits of

the claims involved in the arbitration. The Chief Justice has to decide whether

the applicant has satisfied the conditions for appointing an arbitrator under

05-07-2020 (Page 5 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

Section 11(6) of the Act. For the purpose of taking a decision on these

aspects, the Chief Justice can either proceed or get such evidence recorded,

as may be necessary. We think that adoption of this procedure in the context

of the Act would best serve the purpose sought to be achieved by the Act of

expediting the process of arbitration, without too many approaches to the

court at various stages of the proceedings before the Arbitral Tribunal.

A glance on this para would suggest the scope of order under Section 11(6) to be

passed by the Chief Justice or his Designate. In so far as the issues regarding

territorial jurisdiction and the existence of the arbitration agreement are concerned,

the Chief Justice or his Designate has to decide those issues because otherwise the

arbitration can never proceed.

Thus the Chief Justice has to decide about the territorial jurisdiction and also whether

there exists an arbitration agreement between the parties and whether such party has

approached the court for appointment of the Arbitrator. The Chief Justice has to

examine as to whether the claim is a dead one or in the sense whether the parties

have already concluded the transaction and have recorded satisfaction of their mutual

rights and obligations or whether the parties concerned have recorded their

satisfaction regarding the financial claims. In examining this if the parties have

recorded their satisfaction regarding the financial claims, there will be no question of

any issue remaining. It is in this sense that the Chief Justice has to examine as to

whether their remains anything to be decided between the parties in respect of the

agreement and whether the parties are still at issue on any such matter. If the Chief

Justice does not, in the strict sense, decide the issue, in that event it is for him to

locate such issue and record his satisfaction that such issue exists between the

parties. It is only in that sense that the finding on a live issue is given. Even at the

cost of repetition we must state that it is only for the purpose of finding out whether

the arbitral procedure has to be started that the Chief Justice has to record

satisfaction that their remains a live issue in between the parties.

The same thing is about the limitation which is always a mixed question of law and

fact. The Chief Justice only has to record his satisfaction that prima facie the issue

has not become dead by the lapse of time or that any party to the agreement has not

slept over its rights beyond the time permitted by law to agitate those issues covered

by the agreement. It is for this reason that it was pointed out in the above para that it

would be appropriate sometimes to leave the question regarding the live claim to be

decided by the Arbitral Tribunal. All that he has to do is to record his satisfaction that

the parties have not closed their rights and the matter has not been barred by

limitation. Thus, where the Chief Justice comes to a finding that there exists a live

issue, then naturally this finding would include a finding that the respective claims of

the parties have not become barred by limitation.

12. Applying these principles to the present case, it will be seen that the Designate

Judge has clearly recorded his satisfaction that the parties had not concluded their

claims. We must, at this stage, note that after the first agreement which clearly

covers the issue regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI, the said issue kept haunting the

parties time and again. We have already referred to the agreements and their

cancellations. The first agreement was on 27.4.1994 which is the basic agreement.

The parties then entered into a second agreement dated 18.7.1994 which was

necessitated on account of the fact that then the appellant could make available only

86725 sq.ft. of FSI. It was under this agreement that the appellant agreed that the

further land measuring 2500 sq.mtrs. would be allowed to be developed by the

respondents which land was reserved by Bombay Municipal Corporation for Municipal

05-07-2020 (Page 6 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

Primary School and playground. By that agreement, the appellant undertook to shift

the said reservation to some other property. This agreement was followed by a

Tripartite Agreement dated 9.11.1994 where a third party, namely, Bhupendra Capital

& Finance Limited joined. On 22.6.1996 the agreement dated 18.7.1994 was

cancelled by the mutual consent as the parties were unable to agree regarding the

cost of shifting the reservation further, thereby the third party, namely, Bhupendra

Capital & Finance Limited was excluded. If the things had remained at this stage,

there was no question of the issue regarding the 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI remaining

alive. However, it is clear from the developments thereafter that this issue remained

burning in between the parties which is evident from the fact that the respondents

moved an application under Section 9 of the Act on 4.5.2001 in respect of 2500

sq.mtrs. of land obviously to safeguard their interest regarding the 1,20,000 sq.ft. of

FSI. It is obvious that this FSI was linked with the aforementioned land measuring

2500 sq.mtrs. Though the respondents failed in their attempt to get an injunction

under Section 9 of the Act, they did not leave the things at that and brought in the

such issue firstly by serving the notice dated 11.6.2002 invoking the arbitration

clause and secondly by including this issue in their writ petition filed before the Delhi

High Court wherein the appellants were made to give an undertaking that they will

not sell the property which was covered under the agreement dated 27.4.1994 which

obviously included the 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI. Now this undertaking is still continuing.

It is not for us to go into the correctness or otherwise of the order passed by the

Delhi High Court regarding the undertaking because that is not the question pending

before us, however, it only shows that the parties had not closed the question

regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI. As if all this was not sufficient, lastly the parties

agreed on 19.1.2005 for a MoU where this precise question came up. There, it seems

the respondent had agreed to leave their claim regarding the 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI.

It, however, seems that the respondent wriggled out of the MoU and cancelled it and

chose to serve the arbitration notice for appointment of the arbitrators.

1 3 . Learned Counsel Shri Salve points out that this was not possible as the

respondent could not wriggle out of the commitment made in the MoU and could not

have unilaterally cancelled the MoU as the respondent had accepted to give up their

claim for a consideration of Rs. 1.20 crores and had accepted part payment of Rs. 10

lakhs out of the same. We must state here that it will not be for us to decide as to

whether the respondents were within their rights to repudiate the MoU and serve the

notice of arbitration. What would be the rights of the parties on account of entering

into a MoU dated 19.1.2005 would not be for us to decide sitting in this jurisdiction.

We have only to adjudge as to whether the parties were still at loggerheads as

regards the present issue. The very necessity felt on their part for a MoU would

suggest that the issue was not closed. Shri Salve argues that the respondents could

not be allowed now to revert back on the agreement dated 27.4.1994 once it had

chosen to close the issue by entering into the MoU dated 19.1.2005. Learned Senior

Counsel sought our finding on that. We have already clarified that it will not be for us

to give that finding. In our opinion the very fact that the parties chose to create the

MoU dated 19.1.2005 suggests that the order regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI was

never closed or atleast was never treated to have closed and in that sense it was still

a live issue. Learned Counsel Shri Salve relied upon the decision in Nathani Steels

Ltd. v. Associated Constructions . Our attention was drawn particularly to

contents of paragraph 3 which are as under:

...once there is a full and final settlement in respect any particular dispute or

difference in relation to a matter covered under the Arbitration clause in the

contract and that dispute or difference is finally settled by and between the

05-07-2020 (Page 7 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

parties, such a dispute or difference does not remain to be an arbitrable

dispute and the Arbitration clause cannot be invoked even though for certain

other matters, the contract may be in subsistence. Once the parties have

arrived at a settlement in respect of any dispute or difference arising under a

contract and that dispute or difference is amicably settled by way of a final

settlement by and between the parties, unless that settlement set aside in

proper proceedings, it cannot lie in the mouth of one of the parties to the

settlement to spurn it on the ground that it was a mistake and proceed to

invoke the arbitration clause. If this is permitted the sanctity of contract, the

settlement also being a contract would be wholly lost and it would be open

to one party to take the benefit under the settlement and then to question the

same on the ground of mistake without having the settlement set aside.

Though the observations at the first blush appear to be in favour of the appellants, on

the closer look they are not so. This was a case where in a contract the parties had

amicably settled their disputes and the parties also did not dispute that the they have

arrived at such a settlement. It is under those circumstances that the observations

were made. However, we do not think that the facts in the present case suggest that

there was a full and final settlement in between the parties in respect of the issue

regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI and that a MoU was signed wherein the respondent

and Bhupendra Capital & Finance Limited who was the party to the third agreement,

acknowledged that they were left with rights limited to 86,725 sq.ft. of FSI. It must

be seen that there is no reference whatsoever to any consideration as regards the

1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI, much less to the figure of Rs. 1.20 crores in this MoU. As to

what would be the effect of this MoU on the rights of the respondent herein would

not be for us to go into but it is certain that the issue had not been settled

completely. In Nathani's case (supra) the issue was admittedly settled and that was

not disputed by the parties thereto. Here the parties and more particularly the

respondents are seriously disputing that the issue regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft. of FSI

was finally settled in between the parties. It would be only for the Arbitral Tribunal to

decide the effect of the respondent having signed the MoU. We have pointed out

earlier that this MoU cannot be said to be in the nature of a contract. In Nathani's

case the settlement was viewed as a contract and it was, therefore, reiterated that if

the parties are allowed to wriggle out of their obligation from the contract, no

sanctity would be left to the settlement which are in the nature of a contract. It is for

this reason that, in our opinion, the decision in Nathani's case is not applicable to

the present facts. We also reiterate at this juncture that the cloud on 2500 sq.mtrs. of

land which is inexplicably connected with the FSI of 1,20,000 sq.ft. created by the

undertaking given before the Delhi High Court still remains looming large and

remained so even on the date of the MoU. It is for this reason also that we are of the

clear opinion that there was no final settlement of the issue regarding 1,20,000 sq.ft.

of FSI even by the MoU dated 19.1.2005. If that was so, it is clear that there was live

issue in between the parties and the parties were at loggerheads on that issue.

14. Once we have come to the conclusion that the learned Designate Judge was right

in holding that there was a live issue, the question of limitation automatically gets

resolved. This Court in Hari Shanker Singhania's case (supra) held that till such

time as the settlement talks are going on directly or by way of correspondence no

issue arises and with the result the clock of limitation does not start ticking. This

Court observed:

Where a settlement with or without conciliation is not possible, then comes

the stage of adjudication by way of arbitration. Article 137 as construed in

05-07-2020 (Page 8 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

this sense, then as long as parties are in dialogue and even the differences

would have surfaced it cannot be asserted that a limitation under Article 137

has commenced. Such an interpretation will compel the parties to resort to

litigation/ arbitration even where there is serious hope of the parties

themselves resolving the issues. The learned Judges of the High Court, in our

view have erred in dismissing the appellants' appeal and affirming the

findings of the learned Single Judge to the effect that the application made

by the appellants under Section 20 of the Act, 1940 asking for a reference

was beyond time under Article 137 of the Limitation Act....

As already noticed, the correspondence between the parties in fact, bears out

that every attempt was being made to comply with and carry out the

reciprocal obligations spelt out in the agreement between the parties.

These observations would clearly suggest that where the negotiations were

still on, there would be no question of starting of the limitation period.

15. According to Shri Salve, learned Counsel appearing on behalf of the appellants

the clock had started ticking against the respondents in relation to the agreement

dated 27.4.1994 and they could have had only three years period for filing a suit as

per Article 137 of the Limitation Act and as such the claim made with reference to

that agreement cannot be arbitrable now in the year 2005. We do not agree. It is for

this reason alone that we have given the complete history of the negotiations in

between the parties. The things do not seem to have settled even by 19.1.2005 but

that would be for the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. We only observe, at this stage, that

the claim of the respondent cannot be said to have become dead firstly because of

the settlement or because of lapse of limitation. What is the effect of MoU dated

19.1.2005; was the respondent justified in repudiating the said MoU; and what is the

effect of repudiation thereof on the earlier agreement dated 27.4.1994 would be for

the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. In Groupe Chimique Tunisien SA v. Southern

Petrochemicals Industries Corporation Ltd. MANU/SC/8192/2006 :

AIR2006SC2422 this Court had clearly held in para 10 that the Arbitral Tribunal can

also go into the question of limitation for the claims in between the parties. We have

discussed this subject only to hold that since the issue in between the parties is still

alive, there would be no question of stifling the arbitration proceedings by holding

that the issue has become dead by limitation. We leave the question of limitation also

upon the Arbitral Tribunal to decide.

16. In view of the foregoing discussion we are of the clear opinion that the learned

Designate Judge was right in appointing the Arbitrator under Section11(6) of the Act,

We, therefore, proceed to dismiss the Civil Appeal with no order as to costs.

© Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

05-07-2020 (Page 9 of 9) www.manupatra.com O. P. Jindal Global University

You might also like

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- Shree Ram MillsDocument9 pagesShree Ram MillsRahul ShawNo ratings yet

- Revajeetu Builders and Developers Vs Narayanaswamys091720COM746191Document15 pagesRevajeetu Builders and Developers Vs Narayanaswamys091720COM746191Nausheen AnsariNo ratings yet

- Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited vs. Thakorbhai Ranchhodji Desai and Ors. (21.02.2003 - BOMHC)Document9 pagesBharat Petroleum Corporation Limited vs. Thakorbhai Ranchhodji Desai and Ors. (21.02.2003 - BOMHC)Jating JamkhandiNo ratings yet

- Injunction Suit - Pleading Grounds For It and Necessity of Seeking Quashing of Sale AgreementDocument6 pagesInjunction Suit - Pleading Grounds For It and Necessity of Seeking Quashing of Sale AgreementSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- M S. Ambica Construction Vs Union of India On 20 November, 2006Document5 pagesM S. Ambica Construction Vs Union of India On 20 November, 2006Hemanth RaoNo ratings yet

- Judgment: WWW - Livelaw.InDocument24 pagesJudgment: WWW - Livelaw.InLaveshNo ratings yet

- Wellington Associates LTD Vs Kirit MehtaDocument9 pagesWellington Associates LTD Vs Kirit MehtaAnkit KumarNo ratings yet

- Case On Imposition of CostDocument10 pagesCase On Imposition of CostJAYESHNo ratings yet

- Chittaranjan Maity Vs Union of India UOI 03102017 SC20170410171630331COM345858Document7 pagesChittaranjan Maity Vs Union of India UOI 03102017 SC20170410171630331COM345858Simone JainNo ratings yet

- Dispossession of Property-Human & Constitutional RightDocument8 pagesDispossession of Property-Human & Constitutional RightSankanna VijaykumarNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Judgement 2Document6 pagesArbitration Judgement 2Sanjit Kumar DeyNo ratings yet

- 186292022161136164order22 Jun 2022 423599Document15 pages186292022161136164order22 Jun 2022 423599Ajay K.S.No ratings yet

- Kar HC Limitation 429697Document13 pagesKar HC Limitation 429697arpitha do100% (1)

- Failure To Amend The Pleadings Within The Period Specified - Shall Not Be Permitted To Amend Unless The Time Is Extended by The Court. Air 2005 SC 3708Document38 pagesFailure To Amend The Pleadings Within The Period Specified - Shall Not Be Permitted To Amend Unless The Time Is Extended by The Court. Air 2005 SC 3708Sridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- Vipin Sanghi, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2007 (3) ARBLR314 (Delhi)Document7 pagesVipin Sanghi, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2007 (3) ARBLR314 (Delhi)ApoorvnujsNo ratings yet

- Prem Prakash Yadav V Union of IndiaDocument7 pagesPrem Prakash Yadav V Union of IndiaMohammad ShahrukhNo ratings yet

- Hardesh Ores PVT LTD Vs Hede and Company 15052007 S070627COM935335Document14 pagesHardesh Ores PVT LTD Vs Hede and Company 15052007 S070627COM935335nthkur3No ratings yet

- Parasram Pal and Ors.Document15 pagesParasram Pal and Ors.SoundarNo ratings yet

- Abul Kasem MD Kaiser Vs MD Ramjan Ali and Ors 0502BDAD20200908211459079COM802700Document9 pagesAbul Kasem MD Kaiser Vs MD Ramjan Ali and Ors 0502BDAD20200908211459079COM802700Fs FoisalNo ratings yet

- Review Petition (C) D. No. 40966 of 2013 IN Civil Appeal No.7448 of 2011Document74 pagesReview Petition (C) D. No. 40966 of 2013 IN Civil Appeal No.7448 of 2011venugopal murthyNo ratings yet

- Manupatrain1472580700 PDFDocument18 pagesManupatrain1472580700 PDFnesanNo ratings yet

- Sadgi Investment P LTD Vs State of U P and Ors On 20 April 2004Document6 pagesSadgi Investment P LTD Vs State of U P and Ors On 20 April 2004Mahima RathiNo ratings yet

- M.K Saha JudgementDocument19 pagesM.K Saha JudgementsahilNo ratings yet

- Saraswat Trading Agency Vs Union of India UOI 04w010318COM11114Document7 pagesSaraswat Trading Agency Vs Union of India UOI 04w010318COM11114Ishank GuptaNo ratings yet

- Ilr January 2012 PDFDocument194 pagesIlr January 2012 PDFAnonymous NARB5tVnNo ratings yet

- Decree Obtained by Fraud (2003)Document9 pagesDecree Obtained by Fraud (2003)Divyanshu SinghNo ratings yet

- Reportable: Tarun Chatterjee, JDocument22 pagesReportable: Tarun Chatterjee, JVaibhav RatraNo ratings yet

- CWP963200Document21 pagesCWP963200Moni DeyNo ratings yet

- Narpat Singh and Ors Vs Jaipur Development Authoris020361COM917450Document6 pagesNarpat Singh and Ors Vs Jaipur Development Authoris020361COM917450Bharat Bhushan ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Rejection of Plaint - Cause of Action - When Relied Document Is Not Produced 2012 SCDocument22 pagesRejection of Plaint - Cause of Action - When Relied Document Is Not Produced 2012 SCSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- Judgment: 1. Leave GrantedDocument21 pagesJudgment: 1. Leave Grantedvivek303crNo ratings yet

- Friends Colony Dev Committee V State of OrissaDocument8 pagesFriends Colony Dev Committee V State of OrissaVijay Srinivas KukkalaNo ratings yet

- Summary SuitDocument15 pagesSummary SuitRajvi ChatwaniNo ratings yet

- 712 Ved Kumari V Municipal Corporation of Delhi 24 Aug 2023 491204Document6 pages712 Ved Kumari V Municipal Corporation of Delhi 24 Aug 2023 491204Yedavelli BadrinathNo ratings yet

- JAIPRAKASH INDUSTRIES LTD vs. DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY PDFDocument5 pagesJAIPRAKASH INDUSTRIES LTD vs. DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY PDFArun KeerthiNo ratings yet

- 455549Document15 pages455549harshitanandNo ratings yet

- Rakesh Tiwari, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2005 3 AWC 2843allDocument10 pagesRakesh Tiwari, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2005 3 AWC 2843allTags098No ratings yet

- 525 Ravi Khandelwal V Taluka Stores 11 Jul 2023 481516Document5 pages525 Ravi Khandelwal V Taluka Stores 11 Jul 2023 481516bhawnaNo ratings yet

- R.V. Raveendran and H.L. Gokhale, JJDocument12 pagesR.V. Raveendran and H.L. Gokhale, JJutsa sarkarNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate Jurisdiction: ReportableDocument31 pagesIn The Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate Jurisdiction: ReportableShashwat SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of PakistanDocument8 pagesIn The Supreme Court of Pakistanجنيد انور سنڌيNo ratings yet

- Shriya Maini Statement of Purpose Oxford UniversityDocument34 pagesShriya Maini Statement of Purpose Oxford Universityaditya pariharNo ratings yet

- State of Maharashtra V MS. Hindustan Construction Company Ltd. (2010)Document15 pagesState of Maharashtra V MS. Hindustan Construction Company Ltd. (2010)Ryan Denver MendesNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of India: V.N. Khare, C.J., S.B. Sinha and A.R. Lakshmanan, JJDocument4 pagesIn The Supreme Court of India: V.N. Khare, C.J., S.B. Sinha and A.R. Lakshmanan, JJIshank GuptaNo ratings yet

- K - Lubna - and - Ors - Vs - Beevi - and - Ors - 13012020 - SCSC20201401201751251COM791192Document5 pagesK - Lubna - and - Ors - Vs - Beevi - and - Ors - 13012020 - SCSC20201401201751251COM791192Ryan MichaelNo ratings yet

- Jitendra Kumar Khan Vs The Peerless General FinanW980368COM908765Document8 pagesJitendra Kumar Khan Vs The Peerless General FinanW980368COM908765Dipali PandeyNo ratings yet

- Chandavarkar Sita Ratna Rao Vs Ashalata S Guram 25s860531COM880586Document21 pagesChandavarkar Sita Ratna Rao Vs Ashalata S Guram 25s860531COM880586giriNo ratings yet

- Manokaram Al Subramaniam V Ranjid Kaur Ap Nata SinghDocument15 pagesManokaram Al Subramaniam V Ranjid Kaur Ap Nata SinghJJNo ratings yet

- The Competent Authority Calcutta Under The Land CeSC20190103191702212COM747071Document16 pagesThe Competent Authority Calcutta Under The Land CeSC20190103191702212COM747071SekharNo ratings yet

- Civil Appeal No. 21 of 1985Document10 pagesCivil Appeal No. 21 of 1985Abdullah BhattiNo ratings yet

- Jasoda Debi Vs Ramchandra Shaw and Ors. On 25 February, 2002Document4 pagesJasoda Debi Vs Ramchandra Shaw and Ors. On 25 February, 2002srivani217No ratings yet

- Apollo Zipper India Limited Vs W Newman and Co LtdSC20182704181641275COM490791Document10 pagesApollo Zipper India Limited Vs W Newman and Co LtdSC20182704181641275COM490791PRAKRITI GOENKANo ratings yet

- Madras HC ContemptDocument19 pagesMadras HC ContemptLive LawNo ratings yet

- Frankfinn Aviation CaseDocument19 pagesFrankfinn Aviation CaseRobin FreyNo ratings yet

- Shamsher Singh and Ors Vs Nahar Singh PDFDocument14 pagesShamsher Singh and Ors Vs Nahar Singh PDFSatamita GhoshNo ratings yet

- Arbitratoin Clause in ContractDocument278 pagesArbitratoin Clause in ContractSaddy MehmoodbuttNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Order - AV RANGA rAODocument26 pagesSupreme Court Order - AV RANGA rAOrdonrtNo ratings yet

- Satya Pal Anand Vs State of MP and Ors 25082015 SSC20152808151119391COM951565Document24 pagesSatya Pal Anand Vs State of MP and Ors 25082015 SSC20152808151119391COM951565ABNo ratings yet

- MANU/SC/0454/2005: Ruma Pal and AR. Lakshmanan, JJDocument9 pagesMANU/SC/0454/2005: Ruma Pal and AR. Lakshmanan, JJJating JamkhandiNo ratings yet

- Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2006SC 3275, 2007 (1) ALLMR (SC) 435, 2006 (65) ALR 331, 2006 (6) ALT53 (SC), 2006 (3) ARC 766, 2006 (4) AWC 3907Document10 pagesEquiv Alent Citation: AIR2006SC 3275, 2007 (1) ALLMR (SC) 435, 2006 (65) ALR 331, 2006 (6) ALT53 (SC), 2006 (3) ARC 766, 2006 (4) AWC 3907Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- New Doc 2020-08-29 16.55.42Document1 pageNew Doc 2020-08-29 16.55.42Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- (1999) 7SC C 1, (1999) Supp1SC R560Document18 pages(1999) 7SC C 1, (1999) Supp1SC R560Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Transmission Corporation of AP LTD and Ors Vs Lancs050831COM995260Document13 pagesTransmission Corporation of AP LTD and Ors Vs Lancs050831COM995260Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- TRF LTD Vs Energo Engineering Projects LTD 0307201SC20171807171045272COM952734Document20 pagesTRF LTD Vs Energo Engineering Projects LTD 0307201SC20171807171045272COM952734Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Nawal Kishore Sharma Vs Union of India UOI 0708201s140652COM103758Document9 pagesNawal Kishore Sharma Vs Union of India UOI 0708201s140652COM103758Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Manohar Lal D by Lrs Vs Ugrasen D by Lrs and Ors s100414COM113885Document12 pagesManohar Lal D by Lrs Vs Ugrasen D by Lrs and Ors s100414COM113885Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- V.N. Khare, C.J., S.B. Sinha and S.H. Kapadia, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2004SC 2321Document7 pagesV.N. Khare, C.J., S.B. Sinha and S.H. Kapadia, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2004SC 2321Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Vibhu Bakhru, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2018VIIAD (Delhi) 106, 253 (2018) DLT219Document6 pagesVibhu Bakhru, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2018VIIAD (Delhi) 106, 253 (2018) DLT219Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- R. Banumathi and A.S. Bopanna, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: (2019 (163) FLR443), 2019LLR1058Document3 pagesR. Banumathi and A.S. Bopanna, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: (2019 (163) FLR443), 2019LLR1058Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Bharat Amratlal Kothari Vs Dosukhan Samadkhan Sinds091793COM637924Document11 pagesBharat Amratlal Kothari Vs Dosukhan Samadkhan Sinds091793COM637924Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- 5.1. International Conventions and Fair UseDocument66 pages5.1. International Conventions and Fair UseAman BajajNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of India: M. Jagannadha Rao and Y.K. Sabharwal, JJDocument17 pagesIn The Supreme Court of India: M. Jagannadha Rao and Y.K. Sabharwal, JJAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Bharat Barrel and Drum MFG Company Private LTD ands710502COM177090Document11 pagesBharat Barrel and Drum MFG Company Private LTD ands710502COM177090Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- The Dexterity School of Leadership and Entrepreneurship (Dexschool)Document4 pagesThe Dexterity School of Leadership and Entrepreneurship (Dexschool)Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Table Of: Instruction Kit For Eform Sh-7Document12 pagesTable Of: Instruction Kit For Eform Sh-7Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Format of Consumer EvidenceDocument2 pagesAffidavit Format of Consumer EvidenceAman Bajaj100% (1)

- Early Hearing Application in Admitted Matters: VersusDocument35 pagesEarly Hearing Application in Admitted Matters: VersusAman BajajNo ratings yet

- 2008 31 1501 21915 Judgement 05-May-2020Document159 pages2008 31 1501 21915 Judgement 05-May-2020Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- S.No Name of The Employer Batch Students SelectedDocument3 pagesS.No Name of The Employer Batch Students SelectedAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Legal Drafting: 1. Petition For Divorce 2. Application Under Section 125, CRPCDocument11 pagesLegal Drafting: 1. Petition For Divorce 2. Application Under Section 125, CRPCAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Evidence Project Edit 1Document19 pagesEvidence Project Edit 1Aman BajajNo ratings yet

- Association LTD, The Supreme Court Provided That The Articles ofDocument21 pagesAssociation LTD, The Supreme Court Provided That The Articles ofAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Env. LawDocument16 pagesEnv. LawAman BajajNo ratings yet

- DMD Recruitment January 2019 PDFDocument2 pagesDMD Recruitment January 2019 PDFAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Project Report ON Dishonoring of Cheques: Submitted To Submitted byDocument2 pagesProject Report ON Dishonoring of Cheques: Submitted To Submitted byAman BajajNo ratings yet

- Plan B ModuleDocument220 pagesPlan B ModuledamarwtunggadewiNo ratings yet

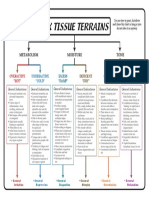

- 6 Tissue Terrains ColorDocument1 page6 Tissue Terrains Colorஆ.க.கோ. இராஜேஷ்வரக் கோன்No ratings yet

- Clybourne Apartments Final ScriptDocument25 pagesClybourne Apartments Final Scriptnasmith55No ratings yet

- Topic 5 - Market Forces - SupplyDocument5 pagesTopic 5 - Market Forces - Supplysherryl caoNo ratings yet

- UNM Environmental Journals: Ashary Alam, Muhammad Ardi, Ahmad Rifqi AsribDocument6 pagesUNM Environmental Journals: Ashary Alam, Muhammad Ardi, Ahmad Rifqi AsribCharles 14No ratings yet

- Supply PPT 2 3Document5 pagesSupply PPT 2 3Yada GlorianiNo ratings yet

- Legacy - Wasteland AlmanacDocument33 pagesLegacy - Wasteland AlmanacВлад «Befly» Мирошниченко100% (3)

- Judicial & Bar CouncilDocument3 pagesJudicial & Bar Councilmitch galaxNo ratings yet

- Resume of Shabina SanadDocument4 pagesResume of Shabina SanadShabina SanadNo ratings yet

- Directory of Licenced Commercial Banks Authorised NOHCs Jan 2023Document19 pagesDirectory of Licenced Commercial Banks Authorised NOHCs Jan 2023Ajai Suman100% (1)

- Mitchell - Heidegger and Terrorism (2005)Document38 pagesMitchell - Heidegger and Terrorism (2005)William Cheung100% (2)

- 2112 Filipino Thinkers PDFDocument4 pages2112 Filipino Thinkers PDFHermie Rose AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Free RebuttalsDocument5 pagesFree RebuttalsKawin Thoncompeeravas100% (1)

- God Has A Name SampleDocument37 pagesGod Has A Name SampleZondervan100% (2)

- Route 6 - Canterbury - GreenhillDocument6 pagesRoute 6 - Canterbury - GreenhillNathan AmaizeNo ratings yet

- Weidner - Fulcanelli's Final RevelationDocument22 pagesWeidner - Fulcanelli's Final Revelationjosnup100% (3)

- Crossed Roller DesignGuideDocument17 pagesCrossed Roller DesignGuidenaruto256No ratings yet

- 1 Whats NewDocument76 pages1 Whats NewTirupati MotiNo ratings yet

- Gram Negative RodsDocument23 pagesGram Negative RodsYasir KareemNo ratings yet

- Florentino v. Encarnacion, 79 SCRA 192Document3 pagesFlorentino v. Encarnacion, 79 SCRA 192Loren Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- The Teaching ProfessionDocument119 pagesThe Teaching ProfessionhelmaparisanNo ratings yet

- Re Kyc Form For Nri Amp Pio CustomersDocument3 pagesRe Kyc Form For Nri Amp Pio CustomerskishoreperlaNo ratings yet

- Pdi Partial EdentulismDocument67 pagesPdi Partial EdentulismAnkeeta ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Highland GamesDocument52 pagesHighland GamesolazagutiaNo ratings yet

- Hci - Web Interface DesignDocument54 pagesHci - Web Interface DesigngopivrajanNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument18 pagesBackground of The StudyCely Marie VillarazaNo ratings yet

- Atelerix Albiventris MedicineDocument5 pagesAtelerix Albiventris MedicinemariaNo ratings yet

- Program SimpozionDocument119 pagesProgram Simpozionmh_aditzNo ratings yet

- Mass GuideDocument13 pagesMass GuideDivine Grace J. CamposanoNo ratings yet

- Best of Mexican CookingDocument154 pagesBest of Mexican CookingJuanNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- The Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeFrom EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (92)

- Summary of The Algebra of Wealth: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityFrom EverandSummary of The Algebra of Wealth: A Simple Formula for Financial SecurityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Broken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterFrom EverandBroken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Financial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassFrom EverandFinancial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassNo ratings yet

- I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)From EverandI Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Summary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)

- Summary of 10x Is Easier than 2x: How World-Class Entrepreneurs Achieve More by Doing Less by Dan Sullivan & Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of 10x Is Easier than 2x: How World-Class Entrepreneurs Achieve More by Doing Less by Dan Sullivan & Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (25)

- How to Day Trade for a Living: A Beginner's Guide to Trading Tools and Tactics, Money Management, Discipline and Trading PsychologyFrom EverandHow to Day Trade for a Living: A Beginner's Guide to Trading Tools and Tactics, Money Management, Discipline and Trading PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Baby Steps Millionaires: How Ordinary People Built Extraordinary Wealth--and How You Can TooFrom EverandBaby Steps Millionaires: How Ordinary People Built Extraordinary Wealth--and How You Can TooRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (324)

- Passive Income Ideas for Beginners: 13 Passive Income Strategies Analyzed, Including Amazon FBA, Dropshipping, Affiliate Marketing, Rental Property Investing and MoreFrom EverandPassive Income Ideas for Beginners: 13 Passive Income Strategies Analyzed, Including Amazon FBA, Dropshipping, Affiliate Marketing, Rental Property Investing and MoreRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (165)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeFrom EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Financial Intelligence: How to To Be Smart with Your Money and Your LifeFrom EverandFinancial Intelligence: How to To Be Smart with Your Money and Your LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- A History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationFrom EverandA History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Legacy Journey: A Radical View of Biblical Wealth and GenerosityFrom EverandThe Legacy Journey: A Radical View of Biblical Wealth and GenerosityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (141)

- Sleep And Grow Rich: Guided Sleep Meditation with Affirmations For Wealth & AbundanceFrom EverandSleep And Grow Rich: Guided Sleep Meditation with Affirmations For Wealth & AbundanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (106)

- Bitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America's Kings of BeerFrom EverandBitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America's Kings of BeerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (52)

- Summary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Slow Burn: The Hidden Costs of a Warming WorldFrom EverandSlow Burn: The Hidden Costs of a Warming WorldRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Unshakeable: Your Financial Freedom PlaybookFrom EverandUnshakeable: Your Financial Freedom PlaybookRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (618)

- In-N-Out Burger: A Behind-the-Counter Look at the Fast-Food Chain That Breaks All the RulesFrom EverandIn-N-Out Burger: A Behind-the-Counter Look at the Fast-Food Chain That Breaks All the RulesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (28)

- A Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessFrom EverandA Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (161)

- Meet the Frugalwoods: Achieving Financial Independence Through Simple LivingFrom EverandMeet the Frugalwoods: Achieving Financial Independence Through Simple LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (67)

- Rich Bitch: A Simple 12-Step Plan for Getting Your Financial Life Together . . . FinallyFrom EverandRich Bitch: A Simple 12-Step Plan for Getting Your Financial Life Together . . . FinallyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- The Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindFrom EverandThe Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (231)

- Smart Money Smart Kids: Raising the Next Generation to Win with MoneyFrom EverandSmart Money Smart Kids: Raising the Next Generation to Win with MoneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (188)