Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Centrum Voor Studie en Documentatie Van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA)

Uploaded by

José Manuel MejíaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Centrum Voor Studie en Documentatie Van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA)

Uploaded by

José Manuel MejíaCopyright:

Available Formats

MODERN MINE LABOUR AND POLITICS IN PERU SINCE 1968

Author(s): David Becker

Source: Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, No. 32, MINERS AND MINING IN

LATIN AMERICA (Junio de 1982), pp. 61-86

Published by: Centrum voor Studie en Documentatie van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25675128 .

Accessed: 23/06/2014 09:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Centrum voor Studie en Documentatie van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MODERNMINE LABOURAND POLITICS INPERU SINCE 1968

David Becker

INTRODUCTION

Class analysis is a powerful

tool for comprehending the changing nature of political

domination and social in the process

control of capitalist development. Because they

aim precisely at such a comprehension, dependency approaches to the understanding

of current Latin American development might be expected to make profitable use of

class-analytical To some extent, they have. Stimulated by the nationalist

techniques.

value orientation of dependencismo, various authors have sought to locate the 'taproot

-

of i.e., the root social mechanism by which the purported external

dependency'1

-

shaping of Latin American capitalist development is maintained in the structure, char

acter and political behaviour of national bourgeoisies and middle classes. These have

been described as non-entrepreneurial, subservient to foreign capital, and incapable

of assuming the task of social reconstruction commonly ascribed to the older bour

geoisies of the world Or, it is held that processes of development involving

metropoli.2

transnational capital have the effect of fractionating these classes, destroying the mutual

interest basis of their cohesion, and thus making it impossible for them to assume a de

velopmental leadership role.3

A corollary to this view is that Latin American are of achiev

bourgeoisies incapable

ing consensual control founded on In

consequence,

ideological hegemony. capitalist

development can be neither progressive nor for the popular classes. Local

liberating

classes are therefore to press for an immediate -

working urged transition to socialism

which, given proletarian groups' relatively small numbers and low levels of consciousness

at the present time, inevitably means acceptance of the Leninist model :

thoroughgoing

change directed from on high by a vanguard party of intellectuals and bureaucrats. Their

claim to represent the material interests of the working class has been shown, however,

to rest on sheer

ideology.

I have elsewhere the image of a non-hegemonic

challenged bourgeoisie presented

by dependencismo, at least for an instance of capitalist based on exporta

development

tion of mineral resources :*bonanza I have called it.4 Here I wish to join

development',

with those who have begun to call attention to another weakness

of dependency-oriented

class analysis, viz., its failure thus far to deal empirically with subordinate social forces.^

The task of class analysis, in my opinion, is to treat

'. the formation, and relations of all significant -

practices, class actors most

certainly including the working class, as the latter is essential to the dialectic

1 A term derived

from Hobson (1939) who referred to the 'taproot of imperialism'.

2 for example, Cardoso and Cardoso and Faletto

See, (1972;1973) (1979); also see Evans (1979).

The image of 'heroic' bourgeoisie which these and other authors seem to use as their implicit

standard of what bourgeois performance ought to be is due to Schumpeter The

(1935:42).

concept of bourgeois 'heroism' has been attacked, with special reference to Peru, by Wils

(1979).

3 The most detailed and original exposition of this view is by Sunkel a similar view

(1973);

is set forth more abstractly by Galtung (1971).

4 See Becker (1982).

5 Among them Henfrey (1981) and Sofer (1980).

61

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of capitalist change and transformation. An of bourgeois

analysis and middle

class "fractions", alone, is actually an elite analysis. It is adequate for displaying

the inequities of capitalist development but can conceive of power and control

solely in terms of a "circulation of elites". Since it can neither comprehend

tendencies toward the amelioration of capitalist excesses that arise with the

growth of working-class political cohesion and nor considers the

capabilities,

prospects for bourgeois it presupposes an un

political-ideological hegemony,

dynamic, non-transformatory capitalism which must be maintained in force

by political authoritarianism\ (Emphasis in original.)6

That is, the unevenness of capitalist development is only part of the story. As Bill Warren

in a work,7 the formation of the proletariat as a

emphasised posthumously published

self-conscious class fur sich, despite all its traumas and wrenching dislocations, is itself

a - a

progressive outgrowth of the dialectics of capitalist development fact that must

not be overlooked when assessing the change process that the latter unleashes.

This article presents an empirical study, based on field research in 1977-78 and

1981, of working-class formation and action in the Peruvian mineria, or mining sector.

Peruvian mine labour is an interesting subject for investigation, for the following reasons:

1 Mine labour, established as a of sorts by the 1930*8 and by

proletariat organised

the 1940's, has served as the spearhead of a national labour movement which has

virtually exploded into activity since 1968. It has been able to act as such because

of the centrality of mining exports to the health of the economy.8

2 Rather remarkably in the Latin the explosive

American growth of labour's

context,

organisational place a took

military regime. under

capabilities

3 The growth of the labour movement has had a counterpart in the rise of a dynamic

Left that participates with considerable success in national and local

political

elections.

4 Whereas the threat of labour-Left activity is said to be a major factor

political

in precipitating authoritarian rule, in Peru the military regime surrendered power

in 1980 to a democratically elected civilian government.

The purpose of the study is to investigate the shape of class conflict in today's

Peru; the nature of the state in this and other cases of bonanza the pros

development;

pects for continued civilian rule and political stability; and, closely related to all the

foregoing, the ability of the working class to realise its material interest under the existing

order.

There have been a number of previous studies of working-class formation and

action in the Peruvian mineria, but all of them have concentrated on the workers of

the Cerro de Pasco Corporation (expropriated in 1974, it is now known as CENTRO

MIN.)9 This North American firm, having set up shop in the Peruvian Andes in 1901,

faced the challenge of uprooting peasants from their traditional way of life in order

to build a labour force.

In contrast, there have been no published studies of the 'modern' labour force

of the Southern Peru Copper Corporation, which operates two huge open-pit copper

6 See Becker (1982).

7 See Warren (1980).

8 In 1980, mine and refinery products accounted for 42.6 per cent of export revenues -double

the percentage of the next most significant export, petroleum, and far greater than any other

product. Two mining firms, Southern Peru Copper and CENTROMIN, usually are the country's

largest taxpayers.

9 See Bonilla (1974), DeWind (1977), Flores (1974), Kapsoli (1975), Kruijt andVellinga (1979);

see also Morello (1976), Ocampo (1972) and Sulmont (1974;1975).

62

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

mines in the southern Andean foothills of Moquegua and Tacnadepartments. Though

only about a third the size of Cerro's workforce at its largest, this small working-class

in Southern's highly capital intensive installations, has been a true pro

body, engaged

letariat from the start. It

also enjoys great economic leverage, since Southern alone

produces 70 per cent of Peru's annual copper output. This work therefore focuses

primarily on the workers of Southern and, to a lesser extent, their comrades in two other

modern mining enterprises in the south of Peru: the Marcona iron mine (operated since

its 1974 nationalisation by HIERROPERU) and the new parastatal enterprise,MINERO

PERU. However, it also deals with the Cerro situation and with another neglected work

group: the workers of the mostly nationally owned private sector of medium mines

(the mediana mineria).

THE HISTORICAL PROCESS OF CLASS TRANSFORMATION IN THE MINERIA

The operations of Cerro and Southern define two epochs of proletarian class

formation in Peruvian mining. One began in 1901 and was concentrated in the central

Andean sierra where Cerro and much of the mediana mineria operate. The other began

around 1954 and involves the capital intensive mining that have

operations developed

in recent times in the foothills of the southern sierra and along the south-central coast.

The protagonists of the first epoch were peasants, most of them very much tied to the

traditional agricultural economy of the or the comunidad. Those

latifundio indigenous

of the second epoch have been mostly ex-peasant migrants from the altiplano and urban

barriada dwellers.

Cerro in its first years was a neocolonial outpost, its zone of operations virgin

territory for capitalism. The woefully debile authority of the state had not yet established

itself with permanence in the sierra; and labour Cerro's

recruiters, once their needs

grew beyond what the few small, old mining towns could encountered a stably

supply,

entrenched peasantry. It was a peasantry resistant to mine labour. Cerro

particularly

created a coercive means, at a time when state power was feeble

proletariat by largely

and when capitalists customarily evinced not the slightest concern for workers' human

welfare. As a result, the as a state-within-a-state, fierce

company operated engendering

nationalist resentment of its 'enclave' character and its maltreatment of its workforce.

That resentment endured over the years the later amelioration of the worst

despite

- as a

exploitative conditions did 'social debt' to the popular classes, of

compounded

past abuses and the company's inability or refusal to improve the Dickensian conditions

in most of its mining camps.

Proletarian class formation mines in the

of the south has had little

large open-pit

in common with what occurred

centre, in

the the

end point is quite similar

although

in certain Here the companies -

respects. Southern Peru Copper, with its Toquepala

mine and Ilo smelter, and Marcona with its iron mine and processing

Mining, plants

at San Juan and San Nicolas -

needed relatively small numbers of workers. Marcona

employed some 2,800 and Southern 4,000. But these had to be trained at considerable

expense to operate costly and The could not allow

complex equipment. companies

this training expense to leak away in high labour turnover. Moreover, they could not

aware that a few disaffected workers

help being might easily wreak enormous

damage

through inattention or Hence, a stable and contented workforce

sabotage. reasonably

was always of great to them. to attain it in part

importance They hoped by offering

very high wages and salaries by local standards; in part clean and commo

by setting up

dious mining camps fully equipped with modern excellent and

hospitals, schools, ample

social amenities; and in part by a of benevolent in labour

following policy paternalism

63

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

relations.*0

These firms had an additional advantage in that they did not have to dragoon

unwilling peasants into the mines. The camps, wage and benefit levels and generally

decent labour policies were 'pull* factors. So too was the nature of the work: open-pit

mine labour is not strenuous, takes place out of doors for those who man the

(except

concentrating plant and smelter), and entails few of the physical and health hazards

associated with mining below ground. There were also 'push* factors. By the mid-fifties,

a major from Puno was well under way. This

out-migration department department,

in south-eastern Peru along the Bolivian border and containing the westward extension

of the Bolivian altiplano, had long been one of the country's most backward. Land

maldistribution was extreme, the latifundios highly traditional; a local tradition of

peasant rebellion was very much alive. The region's tenuous equilibrium had been upset

by population growth, by the belated efforts of some of the latifundistas to capitalise

their holdings, and by the spread of modern political ideologies. Under this three-pronged

assault, much of the now 'excess' peasantry decided to try its luck elsewhere. Waves

of punenos flooded into cities and towns all over the southern half of the republic,

where they proceeded to construct the barriadas. Upon hearing of the mine construction

in the southern foothills and coast, they flocked there in force. Southern's and Marcona's

only recruiting problems were deciding whom to hire and damping down complaints

from disappointed aspirants.

Despite their general lack of education and experience, the punenos proved to be

eager learners, were hard workers, and adapted readily to industrial discipline. Unlike

their comrades to the north, the option of returning to a better life in the countryside

was foreclosed to them; deprived of that oudet, they were far more rapid in redefining

their social situation in purely proletarian terms. One measure of the difference is job

tenure: the percentage of Toquepala and Ilo workers who can claim 20 years' tenure,

that they were there at the very start of operations, is exceptionally high;

meaning

and it is becoming common for workers' sons to fill vacancies left by their fathers'

retirement. Another measure is a much greater preoccupation of Southern workers

with promotion and job categorisation than would have been detected at Cerro when

the latter was of a comparable age. A third is workers' attitudes toward the camps.

At Cerro, in spite of

deficiencies,

gross demands for improvement in family living con

ditions only began figure to

centrally in the unions' pliegos de reclamos (collective

-

bargaining proposals) in the early seventies by which time the proletariat there had

been in existence for over seventy years. At Southern, in contrast, the was

proletariat

less than ten years old when it started to press, through the unions, for certain key

improvements in camp conditions.

Yet, the Puno of resistance

tradition did not die out; for, Southern's policy of

benevolent created a sense of oppression no less real for being different

paternalism

from what was felt in Cerro. A principal source of resentment was the company's attempt

to rigidly control many non-work aspects of camp life, including physical movement

in and out of them. This was done in large part, naturally, to keep out 'political trouble

makers' and 'outside But it was also stimulated by paternalistic concerns.

agitators'.

For instance, if the company feared that itwould be held responsible if it allowed shrewd

local tradespeople to enter the camps and cheat its 'unsophisticated' workers. Southern

10 The Guggenheim family, founders and long-time owners of the American Smelting and Refining

Company (Southern's majority owner) were among the early bourgeois critics of the brutali

sation of labour. They practised benevolent paternalism in their U.S. and Mexican mines

from their beginnings at the turn of the century. To my knowledge, no American smelting

mine in Latin America has ever become a focal point of insurrectionary violence, as Cerro

did. See Marcosson (1949).

64

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

also believed that it was important to actively promote the adaptation of workers and

their families to urban conditions; its Division a very

of Social ran

intrusive

Welfare

acculturation programme that many workers regarded as an infringement of their fami

lies' privacy Another example of infringement of privacy was the surprise

rights.11

of apartments conducted the Townsites Division : demerits would be

inspections by

issued for such offences as unauthorised construction, overcrowding, use

improper

and maintenance of sanitary facilities, animals on the premises, etc.12

raising

This resentment corporate

overweening authority, even when wielded

against

for supposedly benign purposes, soon spilled over into resistance to work rules. Discipline

or

for obvious infractions, like unauthorised absence gross tardiness (there are no time

clock controls anywhere in Southern), is accepted as just; but workers have increasingly

demanded a voice in shift assignments, task organisation, job definition, promotion,

and the of Exactly as often in heavily unionised

appointment supervisors. happens

industries in the United States and Britain, changes in work rules instituted unilaterally

by management are invariably for that reason alone, of their effect

opposed irrespective

on workers' routine.

On the other hand, Southern workers have always protested by conducting very

orderly strikes. Unless

engaged in a sit-down or slow-down (much more common here

than in Cerro, as is the tactic of calling out only a certain work section which is espe

-

cially crucial to production signs, I believe, of a higher order of class sophistication),

-

striking workers usually simply stay at home or, since freedom of movement in and out

of the camps was restored, go off for visits. There are few pickets, almost no demonstra

tions; violence is essentially unheard of. Correspondingly, however, the compact network

of residential organisations, and the tendency of wives and children to form support

groups during labour

that Francisco

crises, Zapata describes as typical of mining camp

- are - are not

life13 they typical in the Cerro camps found. Indeed, residential life in

the Toquepala and Ilo camps is felt by Southern social service workers to be quite ano

mic; they report that the company itself has tried to foster block associa

improvement

tions, sports leagues, women's clubs and the like, but has encountered limited

only

success.

The process of unionisation also proceeded in Southern than it had

differently

in Cerro. Outside were never a factor. Instead, the newly hired workers dis

organisers

played from the first the genius for coordination of action that those who have written

on Peruvian squatter settlements have so frequently commented on.14 Unions were

formed to protest against the firm's announcement that about a third of the mine

only

and smelter construction workers were to be retained once the installations went into

regular operation. A strike was called to defend the fledgeling unions when the national

police, acting without having consulted company officials, arrested their leaders. But

Southern promptly recognised the unions without for government

waiting approval

and to bargain with all four of them

proceeded amicably (one each for empleados and

obreros at Toquepala and at Ilo). That was in 1960.

11 Goodsell (1974:169-174) describes the all-pervasive controls that existed in Toque

company

pala in the late 1960's. Among other things, the company a more complete com

enjoyed

munications monopoly than in any other Peruvian town' and made free use of it

'company

to indoctrinate workers in political and social values preferred officials. There

by corporate

was also - and, judging from my visit in 1978, still is - a great on the company's

preoccupation

part with social-sexual morality in the camps, as if the residents were not

responsible adults

and Southern were charged with supervision in loco parentis.

12 Interview with Peter Graves, Toquepala-Ilo townsite manager, June 22 and July 1, 1978.

Such surprise inspections have since ceased.

13 See Zapata (1980).

14 See Coller (1976), Dietz (1969) andMiehl (1976).

65

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

During their firstdecade, the Southern unions, though formally affiliated with the

CTP, were led entirely by their own people and zealously guarded their independence.

Strikes were called on

occasion, but relations with the company were predominantly

The were

unions successful in economic terms : the average

cooperative. spectacularly

basic obrero wage tripled, and a host of unprecedented fringe benefits was won.

Radical ideological ferment reached Southern only after the 1968 'revolution* had

- was no

begun that is, almost nine years later than Cerro. There observable change in the

nonviolent attitude of the rank and file; but, as in the case of the older North American

firm, the altered climate brought forth a new

group of younger, relatively well educated,

highly idealistic labour leaders. They discovered how, in the absence of other grievances,

to use the issues of authority and paternalism to build a militant discov

following. They

ered, too, that the very well paid Southern workers were financially able and willing to

tolerate long strikes if there were payoffs in wage and benefit increases. And, since

Southern had by now come to account for the lion's share of Peruvian copper exports

and was, thanks to high capital intensity, earning very sizeable profits, the military govern

ment was to end such strikes the requisite increases on the company.

happy by imposing

A Southern obrero, Victor Cuadros Paredes, and an attorney who served as an ad

visor to the CGTP,1^ Ricardo Diaz Chavez, eventually as the leaders of the radi

emerged

cals. They led the unions out of the CTP and into an affiliationwith the CGTP; took over

and reconstituted the FTMMP, whose strength has since been based primarily in Southern;

and later broke with the CGTP to establish the FTMMP as an autonomous political force.

The dream of Cuadros Paredes and Diaz Chavez has been to forge the FTMMP into a true

nationwide federation, whose economic leverage, were it a vehicle for solidarity among all

of the nation's mine, smelter and refinery workers, would obviously be enormous. There

were some momentary successes in 1973-1975, it was not long before

but centrifugal ten

dencies, fed by jealousies and ambition as well as by the isolation from each

personal

other of the various work groups, reasserted themselves. The FTMMP maintains a tie with

the UDP, a small 'Maoist* party that participated in the Left coalitions put together for

the 1978 and 1980 elections. But, as is usual in the mineria, UDP electoral strategy has

not been allowed to determine the action of the mine unions.1

15 There are Peruvian federations for industries or trades (e.g., the miners' federation, the

FTMMP), regions (usually a city or a department), and nature of residence (the federations

of the barriadas, or new urban settlements); some

local unions belong to several. The federa

tions are in turn grouped into no less than four national confederations, or centrals -which

also accept as members certain local unions without a federal affiliation. The four are: the

CGTP, currently the largest and a loose associate of the 'orthodox', or 'Muscovite', Communist

Party (PCP); the CTP, tightly controlled by the centre-Left APRA Party; the CNT, once as

sociated with the now defunct Christian Democratic Party; and the CTRP, which originated

in 1973 as the military regime's oficialista central. As if this were not enough, a number of

federations, among them the FTMMP, insist on remaining independent of all four centrals.

Out of the cacophony of institutions, only the CGTP, the CTP (less since 1968 than before),

and the FTMMP have been active in the mines. (The CTRP has some strength in Marcona

but is not otherwise a factor.)

16 Now that the system (union officers are granted a certain annual number of paid

licencia

leaves and travel expenses) has grown to the point where officials can work full time for the

union, labour careerism is becoming possible. The career of Victor Cuadros, who has since

suggests, further, that such a career can become a

become something of a force in the UDP,

- a neat reversal of the earlier efforts

stepping stone into professional politics by party organ

isers to form associated labour unions. Balbi and Parodi (1981: 3-9) complain that too many

union dirigentes view the superficial ideological indoctrination and slogan memorisation that

they receive from radical parties as a kind of personal advancement through 'intellectualisation'.

Note that both authors are active union advisors and are highly sympathetic to the Left cause.

66

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

We may conclude by noting that the installations which went on stream in the

-

1970's Southern's Cuajone mine, MINEROPERU's Cerro Verde open-pit mine and

-

the Ilo copper refinery have drawn their workforces directly from the barriadas of

the nearby cities and towns. Most of these workers have been urbanised for some time

and have semi-industrial

industrial or work Most have

previous experience. belonged

to labour unions before

coming to the mines and have organised new ones

promptly

to represent them as miners, both they and the employers seemingly regarding this as

a natural course of events. MINEROPERU's unions are affiliates of the FTMMP and the

UDP; the Southern unions at Cuajone, a close alliance with and

eschewing Toquepala

Ilo, have thus far remained

independent. Labour relations in all of these installations

-

are generally regarded as very good much better than at Toquepala and Ilo - although

there have been occasional strikes.

If Cerro's tightly cohesive camps and Southern's anomic ones at Toquepala and

Ilo represent two phases in the evolution of the camp as a unique factor in mining-based

proletarianisation, Cuajone and the MINEROPERU facilities are a third the

phase:

virtual disappearance of that factor's significance. The Cerro Verde mine

parastataPs

and its refinery are located very close to, respectively, second

Arequipa (Peru's largest

city) and Ilo town. Consequently, there are no camps; workers draw a housing allowance

in cash but otherwise form part of a generalised urban working class. Cuajone does

have a camp. However, Southern learned from past mistakes in structuring it. Pater

nalistic controls have been avoided, local tradespeople have been to set

encouraged

up businesses in facilities provided for them, large scale services have been contracted

out to national in order to eliminate an 'enclave' and traditional

providers appearance,

and popular entertainments have been

vigorously these means and

promoted. Through

by virtue of its proximity to the

city of Moquegua, has taken on the air of a

Cuajone

'normal' suburban-industrial town with a lively, multidimensional social life.

Let us sum up and draw some tentative conclusions. Each of the two

quickly

principal proletarian groups of the mining sector has its own

developed along path.

The central sierra group, while far older, does not show its age as a proletariat due to

the persistence for a long time of preproletarian features. Its origins in the peasantry

and its special culture of protest have turned out to be effective

for advancing weapons

the group's economic interests, when the national environ

particularly socio-political

ment has been to the peasant tradition. This has been so, by and

receptive large, since

the 'revolution' unleashed its wave of cultural nationalism. However, the group remains

isolated from the working class at large. There are signs that since Cerro's conversion

into a parastatal its new attention to housing,

enterprise, management's schools, etc.,

and to better communication has to undermine the workers' if not

begun populism,

their militance.1 7

necessarily

The Southern mine and smelter workers have of a less troublesome

partaken

and more rapid process of proletarianisation. are also well and militant

They organised

17 In its 1980 annual report, CENTROMIN claims to have completed 178 new apartment build

ings for workers since taking over for Cerro. The number of schools

operated by the enterprise

'has practically tripled' since 1973 and stands at 89; in the same period student enrolment

has jumped from 10,871 to 27,287. Guillermo Florez Pinedo, CENTROMIN's

president (in

terviewed August 23, 1981), believes that the enterprise's new closed-circuit television system

has been particularly beneficial in smoothing relations with the Workers. A special channel

is piped into all areas where television signals are received; it specialises in news about the

- its -

company activities, financial condition, etc. social and cultural events in the camps,

and so on. Naturally, it broadcasts the enterprise's point of view whenever there is a labour

dispute. Note, however, that the system is not monopolistic; Lima and Huancayo television

are also received.

67

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

in the pursuit of their core interests, but their protests are usually without much emo

tional fervour;

certainly, the treatment they have received from their employers is not

such as

to give rise to insurrectionary On tendencies.

the contrary : in terms of both

wages and benefits, they are the most privileged workers in the country. And as regards

the important of upward social mobility versus 'blocked ascent', Southern's

question

advancement and promotion practices, excellent school system, and university scholar

ship programme make it possible for miners to aspire realistically to middle class status

for their children and, sometimes, for themselves. These factors, along with workers'

preferences for retaining their privileged employment until retirement and theirphysical

separation from other industrial centres, keep the Southern group apart from the rest

of the national working class and from the central sierra group. Furthermore, the cul

tural differences between the two groups appear to have inhibited communication and

cooperation.

THE NATURE OF MINE WORKER'S MILITANCE

- - to

The foregoing suggests that appearances radical leadership rhetoric the con

trary notwithstanding, Peruvian miners have developed no more than a 'trade union

consciousness' focusing solely on economic gains for the immediate work group. If so,

this is a politically significant finding. For the workers have been subjected since 1968

to a steady barrage of Leninist propaganda and activity designed to overcome that limita

tion. Much of it, moreover, is delivered we have not by outsiders but by local

(as seen)

union leaders who are otherwise respected and admired.

Workers9Political Opinions

A broad survey of miners' political attitudes and beliefs might settle the question,

but the practical obstacles thereto have yet to be surmounted.18 The best that can be

done at present is to draw upon existing measures of relevant attitudes among empleados

and obreros in the mediana mineria (whose workers' class experiences tend to mirror

those in Cerro) and in the Cerro Verde mine ofMINEROPERU (whose workers aremost

like These opinion surveys are,unfortunately, noncomparable, since

Southern's).19

they were taken three years apart with different instruments. Still, the partial data

are useful, when combined with impressionistic evidence garnered at Southern.

especially

Workers in the medium mines were asked to select from a given list the group

or institution which they held most responsible for the 1974 increases in the cost of

living.Empleados and obreros agreed in assigning culpability primarily to the president

and Council of Ministers, secondarily to owners and the wealthy', and thirdly

'property

to 'middlemen'. But, while roughly equal percentages of empleados and obreros placed

the blame on the propertied classes, significantly more obreros than empleados chose

18 The principalobstacles appear to be the workers' suspicion of any such effort undertaken

by employers or by the state, and the reluctance of the unions and of academics (most of

whom, in Peru, are highly sympathetic toward the former) to assume the task. Could this

reluctance have to do with the fact that the Left has a vested interest in projecting an image

of proletarian radicalism?

19 The mediana mineria survey was taken in 1974, the Cerro Verde survey in 1977. The results

were made available to me on condition that the sources remain anonymous. I can verify,

however, that both are highly reliable. The first survey sampled ten per cent each of the sub

sector's empleados and obreros, balanced by employer, region and job function so as to be

representative. The second questioned the entire workforce.

68

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

to vest it in the political authorities.20 The data therefore imply that the least privileged

workers the 'superstructure', not the structure of class domination,

perceive political

as their enemy. In view of the radical nationalism espoused by many union leaders at the

time of the survey, it is noteworthy that insignificant percentages of both empleados

and obreros felt that the responsibility for rising prices lay with 'U.S. imperialism'.

alone were asked to describe their own class position and to state

Empleados

the half used as the criterion,

basis for their determination. Just under salary while

28 per cent opted for educational attainment. On these grounds, 57 per cent placed

themselves in the 'middle class', 12 per cent in the 'upper middle class', and 22 per

cent in the 'lower middle class'. Empleados also gave more emphasis than obreros to

non-economic, status aspects of work. When asked to state the most important improve

ment that their employer should make, nearly half of the obreros better

requested

housing, and a quarter higher wages. Empleados, in contrast, did not mention salary

at all, and only 10 per cent referred to housing. Instead, a third demanded

'improved

workplace organisation and better employee training', and a similar fraction requested

more educational programmes.

At Cerro workers were instructed to indicate whether or not

Verde, they under

stood the principal differences between the majorpolitical-economic systems of the

modern world, and those who did were encouraged to select their personal preference

from among 'capitalism', 'socialism' and 'communism'. Two thirds of the empleados

and 31 per cent of the obreros answered the first question in the positive. Within the

of more -

group 'knowledgeables', many empleados than obreros 76 per cent versus

57 per cent - to a preference

admitted among the systems. When those with admitted

preferences were asked to specify them, 34 per cent of the empleados and 8 per cent

of the obreros chose 34 and 69 per cent, respectively, selected 'socialism';

'capitalism';

no but 19 per cent of the obreros, for 'communism'; and 24 percent

empleados, opted

of the empleados, but no obreros, declined to state. The results that relatively

suggest

few obreros have a real of current their express

knowledge political

preference ideologies;

for alternatives to capitalism

probably therefore, comes

to a diffuse

closer,

representing

alienation from the existing

order than it does a strong commitment to something dif

ferent. Empleados, for their part, seem to have -

stronger preferences the likely out

come of more education. However, they are less alienated from the status quo and

less attracted to radical alternatives, all of which seems to reflect a belief that the present

system offers opportunities for socio-economic advancement.

In the absence of opinion survey data from the Southern installations, I asked fore

men and line supervisors I met many) to characterise

(of whom the political orientations

of workers under their authority as best I was one who to find

they could. felt unable

that more than a tiny minority of 'his' workers was committed to radical most

ideologies;

characterised the typical worker as generally to vote for the

apolitical, willing, perhaps,

Left but without great enthusiasm. This was confirmed in conversations with

impression

about twenty randomly selected workers. I was also privileged to spend most of a night in

conversation with a group of committed Marxist-Leninists involved in union

deeply

affairs at Ilo; they further confirmed the of rank and file apoliticism.

impression

20 Obrero data were tabulated only by region; overall averages had not been computed in the

version of the report that was shown to me. Those

blaming the president and Council of Min

isters ranged from 40.8 to 70.2 per cent; the data for the two most

populous mining regions

were 56.9 and 48.6 per cent. Those

blaming the propertied classes ranged from 17.5 to 29.2

per cent; 20.6 and 26.8 per cent in the two most populous regions. Those blaming 'middlemen'

ranged from 2.9 to 15.6 per cent. The empleado data did include overall averages. The per

centage of empleados (there were no significant regional differences) blaming the political

authorities, the propertied classes, and 'middlemen' was 33.7, 20.3 and 14.8 respectively.

69

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Militance and Strikes

If we look at working class formation and action in the developed countries, we

encounter too many situations in which workers' readiness to undertake militant class

action to defend common interests bears little evident relation to the ideological orienta

tions of the workers or of the labour unions to which they belong. Has the working class

of the Peruvian mineria, apart from its ideological predilections, shown increasing mili

tance in action during the 1968-1980 period of military rule? The strike record should

provide the answer and should also permit a determination of the degree to which mine

workers have spearheaded the action of the working class at large.

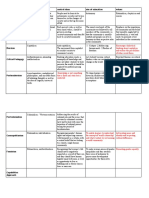

Table 1

STRIKES IN PERU, 1967-1979

Number of strikes Number of strikers Manhours lost to strikes

A B A/A and B C D C/C and D EF E/E and F

Year mine other percent mine other percent mine other percent

1967 32 382 7.7 17,818 124,464 12.5 5,269,664 3,103,108 62.9

1968 21 343 5.8 9,426 98,383 8.7 2,825,376 552,425 83.6

1969 24 348 6.5 17,803 73,728 19.5 1,900,748 1,988,552 48.9

1970 66 279 19.1 56,205 54,785 50.6 4,325,853 1,456,003 74.8

1971 76 301 20.2 58,454 102,961 36.2 6,270,632 4,611,320 57.6

1972 33 376 8.1 16,657 113,986 12.7 958,008 5,373,008 15.1

1973 80 708 10.2 59,471 356,780 14.3 3,831,888 11,856,800 24.4

1974 38 532 6.7 27,433 335,304 7.6 1,878,148 11,534,892 14.0

1975 57 722 7.3 50,387 566,733 8.2 2,652,609 17,616,799 13.1

1976 29 411 6.6 31,505 226,596 12.2 572,228 6,249,996 8.4

- - ---

1977 n/a 234* n/a 406,461* n/a 6,543,352*

1978 53 311 14.5 48,596 1,349,791** 3.5 4,680,388 31,464,348** 12.9

1979 40 537 6.9 25,342 678,141 3.6 1,187,288 9,364,064 11.3

*Data *

for all strikes in the country, mine and other'.

**

Figures are inflated due to a two-day general strike in 1978.

Sources: Yearbook of Labor Statistics 1980, (1980); Las Huelgas en el Peru, 1957-1972, (1973);

unpublished data supplied by the Sociedad Nacional de Mineria y Petroleo.

Table 1 summarises Peruvian strike activity in the mines and elsewhere from 1967

to 1979. We see that there has been no secular toward an increase or decrease

tendency

in the of mine strikes in the national totals: although strikes in the mining

ponderance

sector became especially prominent in 1970-73 (and again, for reasons to be discussed

in 1978), they have generally accounted for a constant six to seven per

subsequently,

cent of the total. On the other hand, the 53,000 obreros and employed in

empleados

the sector21 represent two per cent of all wage earners; and I would guess (as there

only

21 Employment datum furnished by the Sociedad Nacional de Mineria y Petroleo. The datum

omits another 35,000-odd workers employed in the very small mines of the pequena mineria,

most of whom work only part time and few of whom are unionised. The contribution of the

latter subsector to GNP, exports, etc., is negligible.

70

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

has been no census of labour organisations on which to base a more precise estimate)

that less than one per cent of the nation's local unions are situated in the mineria. Miners

have formed

thus a disproportionate

share of strikers in each of these years. Still, this

share has

recently begun to decline. Other evidence suggests that the decline is due

mainly to an increase in strike frequency in the rest of the nonagricultural economy.

To the degree that the mine strikes of the early were

seventies perceived by the rest

of the working class as successful and hence encouraged the latter to engage more often

in job actions, the mine unions could be said to have spearheaded greater working class

militance. However, independent verification of a relationship between the two variables

is needed before that hypothesis can be accepted unequivocally.

In table 2 are shown three measures of strike size and intensity. Until the early

mine strikes tended to involve more workers each than did others - for the ob

1970's,

reason are

vious that mining workforces larger on the average than in any other industry.

But this tendency has reversed since 1975. Inasmuch as there has been neither great

industrial growth nor consolidation in 1975-1979, the change can only be attributed

to the increasing success of non-mining labour federations it should be

(particularly,

noted, such militant 'middle class* federations as those of teachers and bank employees)

in work the effort mounted

fomenting industry-wide stoppages. Contrariwise, by the

FTMMP since 1973-1974, when it came under radical control, to weld all of the local

mine unions into a national force has not borne visible fruit on the strike front.

single

Table 2

INDICATORS OF STRIKE INTENSITY, 1967-79

No. of strikers Manhours lost Manhours lost

per strike per strike* per striker

Year Mine Other Mine Other Mine Other

1967 556.8 325.8 164.7 8.1 296 25

1968 448.9 286.8 134.5 1.6 300

6

1969 741.8 211.9 79.2 5.7 107

27

1970 851.6 196.4 65.5 5.2 2777

1971 769.1 342.1 82.5 15.3 107

45

1972 504.8 303.2 29.0 14.3 47 58

1973 743.4 503.9 47.9 16.7 33 64

1974 721.9 630.3 49.4 21.7 34 68

1975 884.0 784.9 46.5 24.4 31 53

1976 1086.4 551.3 19.7 2715.2

18

1977** n/a 1737.0 n/a 28.0 n/a 16

1978 916.9 4340.2 88.3 101.2

9623

1979 633.6 1262.8 29.7 4717.4

14

* In thousands

** are for all strikes, mine and 'other'

Data

Source: Computed by the author from data in Table 1

Mine strikes have always entailed greater losses of labour time. This used to be

due, once more, to differences in the size of work units but now must be ex

average

laid to a than duration of mine - as

clusively longer average strikes the data for labour

time lost per striker demonstrate. The latter also reveal a clear secular trend

graphically

toward declining militance, a trend in evidence the period.22 It is not con

throughout

22 This phenomenon was first observed and commented upon by Zapata (1980).

71

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

fined to mine workers, however.

Moments of militance in the mines, as in the seventies, coincide

increasing early

with similar tendencies in the working class at large. The implication is that these have

to do with events of national scope.

Table 3

STRIKE INTENSITY INDICATORS BY ENTERPRISE, 1969-1979

Manhours lost per strike (in thousands) Manhours lost per striker

Cerro/ Marcona/ restof Cerro/ Marcona/ rest of

Centromin Southern HierroP. sector Centromin Southern HierroP. sector

1969 169.8 315.3 0.0 25.3 95 146 0 93

1970 92.9 58.2 76.1 34.9 66 818170

1971 82.1 68.8 215.5 73.1 69 99 107 162

1972 4.1 48.2 0.0 16.5 170

31 86

1973 131.0 72.9 110.8 35.0 1681

91 75

1974 282.5 186.2 0.0 30.5 24 79 0 216

1975 59.8 105.9 0.0 25.8 750

4656

1976 147.2 26.7 0.0 11.3 160

22 17

1977 92.6 54

101.6

1978 85.2* 117 92*

50.6

1979 21.7*96 32*

* Data are for all enterprises Southern

except

Sources: Per table 1; also, Southern's consolidated declarations for 1977-1979, filed with the

Ministerio de Energia y Minas.

Table 3, which

partially breaks down by enterprise two indicators of mining sector

strike intensity, permits us to correlate militance with the working class groups defined

earlier. The trend toward decreasing militance (it appears most vividly in the right half

of the table) is here seen to be especially in evidence among the Cerro group.Since the

1974 nationalisation, CENTROMIN workers have become less militant on the average

than those of the mediana mineria, who account for the bulk of the 'rest of the sector'.

Given that the trend firstbecomes plain in 1973, when the impending expropriation of

the firm was already public knowledge, it would appear that the transfer of the enterprise

to national control has definitely helped to reduce strike intensity. Sceptics might argue

that the state, as employer, has repressed the labour movement more strenuously than

before, or at least that it has lowered the payoffs to militance by firmly resistingwage

demands. data, to be examined shortly, refute the second accusation. There is a

Wage

of truth to the first; but was felt after1976, was never

grain repression only seriously

extreme and affected the entire mining sector. More important, it seems to me,

equally

has been the quick the new parastatal

action management to clear Cerro's 'social debt*

by

and to improve its communications with workers.23

Workers at Southern Peru a greater degree of militancy. It is cy

Copper display

clical, peaking at four- to five-year intervals with little apparent long term change. A

23 Florez Pinedo (see note 17) claims that CENTROMIN's television communication system is

undermining the old habit of wives' supporting and participating in miners' protests. Instead,

they hear the broadcast company viewpoint while at home and urge their husbands not to

strike. Such behaviour has always been typical at Southern.

72

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

comparison with the near-passivity of the Marcona (HIERROPERU, after its 1974

workers, whose backgrounds and working conditions are similar, suggests

nationalisation)

that workers employed by a very profitable foreign firm (which Southern is) perceive

much greater opportunities for gains than do those employed by one which is neither.24

out at Southern

(I have already pointed that the very high wages enable its workers

to withstand long strikes better than any other working class group.) In view of what

has been learned about the different class formation histories of the Cerro and the South

ern-Marcona work groups, it can only be concluded that militance in the Peruvian mines

no longer has anything to do with political parties or outside direction, with populist

causes the disruption of traditional peasant life by advancing or with

(i.e., capitalism),

gross oppression. It must be regarded, rather, as a natural outgrowth of proletarian

maturity.

'ECONOMISM' AMONG THE WORKING CLASS ?

'Economistic' class action is predicated on the that the principal in

assumption

terest of the working class is to augment its share of the economic It is therefore

pie.

relatively unconcerned with challenging the structures of political domination and social

control which keep the class in its subordinate condition; and itmay entail an acceptance

of bourgeois strategies for enlarging the pie. That key elements of the working class

incline toward 'economistic' patterns of action does not mean that bourgeois hegemony

exists. It does mean that the attainment of bourgeois is possible,

hegemony provided

that the latter class can do two : meet a satisfying of the 'economistic'

things (1) portion

demands without excessive sacrifice of its own interest in power and control; (2) also

without such a sacrifice, accomodate within its own world view the existence and ac

- -

tivities of those indigenous institutions labour unions, Left political etc., which

parties,

the working class has constructed and deems essential for its self-protection. The actions

of corporate mining enterprises in Peru since 1968 appear to conform to the second

requirement. What of the first ?

The Evolution of Real Wages and Benefits

Table 4 describes the recent evolution of average real wages 2^ for the nonferrous

metal-mining industry as a whole; for Southern; for Cerro/CENTROMIN; and for the

mediana mineria. Also indicated, for purposes of comparison, is the average nonagri

cultural wage for metropolitan Lima. Most mine workers a steady increase

experienced

in real income until the late 19 70's. Wages thereafter came under downward pressure

as inflation accelerated. Nonetheless, miners held their own better than did Lima work

ers : from 32 per cent in 1968, the average sector remuneration rose to

greater mining

62 per cent greater by 1971 and was still 54 per cent greater in 1977. Under parastatal

Cerro's have attained one of their most -

management, employees finally cherished goals

24 Southern has earned a profit in each year of operation except 1975; total profits for 1971-1980

were $ 393.5

million after taxes. Marcona, in contrast, lost in four of the eight years

money

immediately prior to its nationalisation. The nationalisation itself resulted in a two-year legal

battle with the company and with suppliers holding delivery contracts, because of which very

little iron ore was sold in that period. Since 1976 HIERROPERU has been prevented low

by

iron ore prices and limited dependence from returning to profitability.

25 Wages is defined to include : basic wage or salary; overtime pay; shift

differentials; holiday

pay and Sunday pay (dominical) of obreros; vacation pay; and deferred payments -

employer

contributions to social security and employer set-asides for future payment of time-of-service

indemnities.

73

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

wage parity with the more capital intensive Southern. Even miners employed by the

small, mostly locally owned firms of the mediana mineria have advanced economically

more than industrial workers in general.

Table 4

INDEX OF REAL WAGES IN PERUVIAN MINING AND OTHER INDUSTRY, 1967-79*

=

(100 average wage for all nonferrous metal-mining in 1967)

All

Cerro/ Medium Other

Year Mining Southern CENTROMIN Mining Industry**

100

1967 219 67118

100

1968 217 117

6776

105

1969 216 128

7283

1970

122 264 87

15082

1331971 280 154 100 82

1481972 335 164 114 96

157 1973 402 187 109 108

153 1974 412 190 102 106

164 1975 353 189 123 102

1261976 424 255 104 92

1261977 335 239 109 81

1978

221 107

201 70

1979 207 61

*

Money wages (see note 25 to main text) deflated by the consumer price index for metro

politan Lima.

**

Average nonagricultural wage for metropolitan Lima.

Source: Computed by the author from information contained in company consolidated declara

tions and annual reports as well as from data supplied by the Sociedad Nacional de Mineria

y Petroleo and published in Yearbook of Labour Statistics 1980 (1980).

The situation at Southern is actually not as bleak from the viewpoint of worker

interests as seems to be the case. For, the table does not fully reflect the value of fringe

benefits won there. These include various monthly allowances contingent on family

size and circumstances; paid-up life insurance; disability bonuses and payments to supple

ment national social

security benefits; expenses upon or retiring;

paid moving quitting

free round-trip air fare for vacations to any point in Peru; 95 college scholarships for

workers' children; and full payment of educational expenses incurred by workers who

obtain a certificate of completion from a professional or technical school.

Another economic advance that cannot show up in the wage

data consists in

direct and indirect company contributions to the unions, which relieve the workers

of responsibility for certain costs that would otherwise come out of their pay envelopes.

This process of employer subsidisation of the unions is farthest along at Southern but

is being imitated elsewhere. Officers of the Southern unions receive a total of 2,140

- in

unrestricted man-days of annual licencia up from 340 man-days with restrictions

1970. Federation and confederation officers to the empleado unions are

belonging

granted permanent leaves with full pay. All officers are awarded a company-paid life

and accident insurance policy with a face value of $ 1 million (in 1978). The company

has been to make $326,000 in cash contributions to the unions' building funds

required

74

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and to donate construction materials and labour; it also pays the unions $19,500 per

year in operating and upkeep expenses for their libraries. And, as part of a move to

improve relations with student groups, the unions have obtained a company donation

of $ 142,000 to the universities inTacna and Arequipa.

The wage obtained the mining

by 'labour aristocracy' are consistent with

gains

FitzGerald's conclusion that, compared to some of the larger, more developed countries

of Latin America, Peru in this period showed the least shift of national income toward

the top two deciles of the income distribution and the biggest growth in the share cap

tured by themiddle four.26 The military regime did little to improve the incomes of the

least mobilised sectors; but it was no supporter of upper class

poorest, popular privilege

and did not stand in the way of economic gains by powerful labour groups. It should

further be mentioned in the latter connection that in mining, much larger proportionate

gains were realised by the less

privileged obreros than by the better-off

empleados.

If one assumes that class cohesion is in part of wage an inverse

differentials function

between various working class elements, then the mining proletariat is not doing much

to promote cohesion. On the other hand, cohesion within the mining proletariat has

somewhat increased. (I say 'somewhat' because the geographical cleavage remains.)

The Question of Control over theEnterprise

Were mine workers' class consciousness of a nature that would lead them to take

serious issue with the division of power and authority in the capitalist enterprise, the

Workers' Community System, instituted in 1971, presented them with one possible

vehicle for expressing such a concern. The Workers' Community was an enterprise reform

combining co-ownership with co-management, both to be gradually attained through

reinvestment of a portion of company profits in labour shares held all workers in

by

common.

None of the medium or so far as I have been able to

large mining companies,

determine, ever resorted to borderline or actual fraud in order to evade their obliga

- as

tions under the system happened often in manufacturing. In fact, some of

enough

them have sent Community officers to attend courses

in accounting and business manage

ment. Nevertheless, the mine unions, to regard the system as a cooptative

choosing

device intended to undercut their and promote -

appeal labour-management cooperation

in the minds of the generals, it assuredly was -

which, denounced it and ordered a boycott

of its activities.27 The boycott was fairly well honoured for the first two years. Then,

in 1974, workers started to receive very sizeable distributions from the high industry

profits of the previous year (world metals prices skyrocketed in 1973 and remained

high into As soon as that occurred, interest in Community assemblies and officer

1975).

ships quickly increased. The unions decided not to buck the trend. It was a wise move,

since worker loyalty to organised labour in no way diminished; Community assemblies,

and the actions of Community-appointed directors on the boards,

companies' managing

26 :

FitzGcrald, (1979 140-141). The other countries are Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela.

But if Peru is unique in that the income distribution has been shifting toward the middle

sectors, it is also the case that these have more catching-up to do : in 1973-1974, only in Brazil

did the top five per cent have a larger share of the total national income.

27 Peruvian academic writing on the Workers' Community mirrors the union attitude; see e.g.

Pasara and Santisteban (1973), Pasara et al. (1974) and Alberti, Santisteban and Pasara (1977).

It is possible that in this matter, too, the union and the academic view are not coincidentally

related - which is not, I hasten to add, a disparagement of that view. The question is merely

whether the unions reached their position or were influenced by academics'

independently

analyses. The answer is not known.

75

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

simply became a parallel avenue to the unions for advancing the same class concerns.

These concerns, it is plain, have nothing to do with management under

properly

stood, i.e., with exercising the real decision-making power of corporate capital. Of the

many corporate managers whom I interviewed, not one complained that the Commu

nity's representatives were weakening or undercutting in the enter

capital's authority

Instead, their complaints centred on the

slowing down of directoral business

prise.

-

that occurred whenever Community representatives asked for financial information

information which, in management's view, was invariably used to strengthen union

negotiating positions at bargaining time.

The only non-economic use to which the workers have put the Community is

to bring personnel matters to the attention of top corporate management. Community

appointed directors, acting on behalf of petitioning workers, solicit and

reassignments

promotions, enter objections to the actions of line supervisors, and so forth. Managers

are happy to have this input, as it gives them a chance to defuse that might

problems

otherwise develop into a cause for the unions;

celebre but they would vastly prefer

to see it take place at levels well below that of the board of directors. As for the workers,

they have made plain at Community assemblies, in which they participate democratically,

that this is the function that they want their representatives to perform.

After eight years of experience with the Workers' Communities, the military

regime realised that the system had made no observable difference in the character

of labour-management relations but was acting as a disincentive to new capital invest

ment. Therefore, the system was altered in 1978 to reduce the maximum ownership

stake that workers could attain from 50 to 33 per cent, thereby guaranteeing that private

capital would not lose majority control. One year later the system was modified much

more drastically to eliminate its communitarian aspects and circumscribe its comanage

ment function. Shares of capital stock are now distributed to workers as individual

these acciones laborales may be traded on the Lima Stock

property; freely Exchange.

Just as one would expect, many workers sell them as soon as received, preferring to

have the ready cash. Worker-directors no longer sit on corporate boards, in many cases;

worker input in management affairs may be implemented instead via labour-management

comites de gestion, whose power is far less under the law than that of a board of direc

tors. The institution these wholesale in the system brought not a whim

of changes forth

per of protest from labour leaders orfrom the rank and file. The typical worker prefers

a stock certificate negotiable for currency to an abstract share in the exercise of a dimly

perceived authority.

THE POLITICAL POWER OF ORGANISED MINE LABOUR

Labour and National Power

-

During the first seven years of the Peruvian 'revolution' that is, during the presi

-

dential incumbency of Gen. Juan Velasco Alvarado the regime consistently favoured

the wage demands of the principal mine labour groups. This was done through expanded

use of the state's power to impose wage settlements. As soon as it became obvious to

the mine unions that the government was on their side in matters of pay and benefits,

direct collective between labour andmanagement into a pro

bargaining degenerated

exercise of content. Unions framed extreme demands and refused com

forma empty

promise, expecting that the labour ministry would ultimately grant them much of what

sought. likewise avoided as any company offer

they really Companies compromise,

was now regarded merely as an indicator of the lower limit of what the traffic would

bear. Thus, labour relations in the mines became totally politicised.

76

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The military's initial favouritism toward mine labour is explained by the following:

1. Nationalism. The were nationalists by conviction and shared the percep

generals

tion of all Peruvian nationalists that the foreign resource had been

companies pillaging

the country's resource base for many years. Hence, they were not about to do anything

to uphold the short term interests of the large foreignmining firms against those of a

mobilised and politically vocal group of local citizens. In addition to ideological con

viction, the militares were basing their legitimacy in power on nationalism, on wide

spread public disgust with the entreguismo of previous governments. That the regime

did seek acceptance and legitimacy and did not wish to rule by force alone is demon

strated by its entire record of reform.

2.Social Justice. Not all of the generals were cynical power seekers or techno

cratic elitists; a few, at least, sincerely believed it their duty to help uplift the down

trodden. General Velasco himself, whose humble are well known, may have been

origins

one of these. Another was Gen. Fernandez Maldonado, the minister of mines

Jorge

under Velasco, who had imbibed the doctrines of Social Christianity. Among his earliest

official acts were the disarming of private mining-camp the prohibition of com

police,

pany interference with free movement of persons in and out of the camps, and ordering

the removal of guards and barriers around expatriates' camp quarters. Later on he in

sisted on incorporating into the 1971 Mining Code and its supporting regulations the

first detailed specifications for minimum working conditions and camp facilities in

the mines, and under his a decree-law

leadership setting standards for housing accomoda

tion was enacted. He was particularly sympathetic to the Cerro miners and their 'social

debt'.

3. Bonanza development. The strategy of bonanza development entailed using

the mining industry to underwrite a broader industrial in both its eco

development

nomic and political aspects. Inter alia, the local share in mining of value

and added

refining was to be increased systematically; linkages between mining and other industries

were to be multiplied and enlarged; and mining revenues were to be used in part for co

opting and pacifying restive mobilised elements associated with industrial labour which

a danger to the status quo -

would otherwise pose thereby relieving new industrial capital

of this burden. increases served all of these objectives : the first and third

Wage directly

and obviously; the second in that better

paid miners would add to the market for domes

tically produced manufactured goods. At the same time, efforts to accelerate the pace

of development pressed even more heavily on the balance of payments and on the state's

finances and international borrowing all of which were underwritten

capacity, by mining

revenues. Therefore, strikes and stoppages that interfered with mine had

production

to be ended at any cost.

quickly

4. Antiaprismo. Peruvian The had a tradition of uncompromising

military opposi

tion to the APRA party; it dated from a 1932 massacre of an army garrison by aprista

insurgents. Military seizures of power in 1948, 1962 and 1968 were motivated partly

by a desire to forestall probable APRA successes in forthcoming presidential elections.

-

Up until 1968, most of the party's strength despite repeated flirtationswith the Right,

it was the only well institutionalised not under -

party oligarchic control lay with the

more advanced and better sectors of the working class and with the lower

organised

elements of the middle class, which are also unionised. that would

heavily Anything

undercut aprista appeal to organised labour would weaken it.

seriously

All of the mine unions recognised the military disposition forwhat itwas.

They

therefore concluded that they should station themselves well to the left of the regime,

striking longer and more often to force accomodation on issues but not

pay persisting

for ideological reasons. These tactics, as we saw, were successful. More than

eminently

77

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

that, they protected the labour movement from cooptation.28 The unions cooperated

at firstwith the CGTP, which, having reconstituted itself threemonths before the mili

tary takeover, was the earliest labour beneficiary of the new regime's steadfast opposition

to the CTP. Later, however, when the PCP attempted to become the principal pro-regime

political party and so ordered the CGTP to moderate itsmilitancy, the mine unions

broke with it.

These happy circumstances soured in 1975. Falling metal prices translated into

company and made the companies more resistant than ever to

falling mining profits

union wage demands. In August a seriously ill Velasco was ousted from office and re

a former minister

placed by Gen. Francisco Morales Bermudez, economy whose policy

became one of restoring the weakened economy to health by slowing the

emphasis

pace of reform and reassuring private capital. But the same metal price plunge threw the

balance of payments into deficit and drained the nation's foreign currency reserves,

while food

imports increased to feed the growing urban labour force. Moreover, food

was -

being sold below cost by state monopolies another cooptative benefit of bonanza

-

development and these subsidies helped to unbalance the state budget. The result was

domestic inflation; hitherto much rarer in Peru than in many of the more industrialised

Latin American countries, it would reach runaway proportions by the end of the de

cade.

Had the regime tried actively to mobilise popular support during the halcyon

days of radical reform, it might have been able to ride out the storm sheltered by appeals

to patriotism and national sacrifice. As it was, the appeals were offered but fell on the

deaf ears of a demobilised apathetic public whose

and every attempt to organise politically

had been The only alternative was repression. Early in 1976 another wave

squelched.

of mine strikes broke out as miners strained to protect their purchasing power in the

face of inflation by winning extraordinary wage increases. The regime responded by

declaring a state of emergency in the mining sector and forbidding all strikes therein.

On July 1, 1976 a national state of emergency was put into effect, and six weeks there

after the strike prohibition was made universal.

Yet, the government knew that it was riding a tiger in employing these tactics

against mine labour, and it proceeded with caution. Workers in the large mines, who

could best afford the loss of back pay, regularly defied the strike prohibition; but for

the occasional and brief detention of

leaders, no effort was made to punish them (with

one which turned outdisastrously for the regime). Importantly, fear of

exception,

the miners' reaction undoubtedly stiffened the spine of the government in its negotiations

with the IMF, which was on the imposition of antipopular, deflationary eco

insisting

nomic measures as its price for aiding Peru in its international financial difficulties.

In this the power of the mine unions was latently but effectively, on behalf

deployed,

of the interests of the whole working class and much of the middle class. Of course,

the worsening economic situation made it impossible for the government to resist the

IMF forever. Its resistance collapsed in May 1978, and the package of measures demanded

the international agency was reluctantly enacted. Labour answered with a very effec

by

28 As an example : in 1970 a Cerro marcha de sacrificio, billed as a demonstration against 'im

perialism' as well as in support of miners' wage demands, was granted full police protection

was set up for the marchers, in the

by the government; an encampment upon reaching Lima,

working class district of San Martin de Porras; and a round of visits with President Velasco

and lesser dignitaries was arranged. This was the first time ever that such a demonstration

had been so received, and the purpose in doing so is evident. Yet the miners refused all com

promises offered by the labour ministry, threatened to remain in Lima indefinitely, and even

tually raised their demands even higher than those initially announced. The government had

to cede on all points.

78

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.81 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:57:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

tive general strike on May 22 and 23.29 The government reimposed a state of emer

gency (it had lapsed several months before), but there were no mass arrests or wholesale

firings.

The year 1978 also witnessed the regime's decision to turn power back to civilians,

with the election of a constituent assembly to write a new constitution and

beginning

ending in 1980 with the election of a president, a national legislature, and local officials.

In order to prepare for a smooth transition as well as to seek the cooperation of all

sectors in resolving the economic problem, Morales Bermudez began a round of meetings

with representatives of political parties, property owners' associations, professional

and labour. All of the centrals participated, as did the FTMMP and other