Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J Anfis

Uploaded by

Dewi JuniswatiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J Anfis

Uploaded by

Dewi JuniswatiCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal homepage:

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

www.elsevier.com/locate/issn/20954964

Available also online at www.sciencedirect.com.

Copyright © 2017, Journal of Integrative Medicine Editorial Office.

E-edition published by Elsevier (Singapore) Pte Ltd. All rights reserved.

● Research Article

The anatomical study of the major signal points

of the court-type Thai traditional massage on

legs and their effects on blood flow and skin

temperature

Yadaridee Viravud1, Angkana Apichartvorakit2, Pramook Mutirangura3, Vasana Plakornkul1, Jantima

Roongruangchai1, Manmas Vannabhum2, Tawee Laohapand2, Pravit Akarasereenont2

1. Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700,

Thailand

2. Center of Applied Thai Traditional Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University,

Bangkok 10700, Thailand

3. Division of Vascular Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700,

Thailand

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: This study aims to investigate the relationship between major signal points (MaSPs) of the

lower extremities used in court-type Thai traditional massage (CTTM) and the corresponding underlying

anatomical structures, as well as to determine the short-term changes in blood flow and skin temperature

of volunteers experiencing CTTM.

METHODS: MaSPs were identified and marked on cadavers before acrylic color was injected. The

underlying structures marked with acrylic colors were observed and the anatomical structures were

determined. Then, pressure was applied to each MaSP in human volunteers (lateral side of leg and

medial side of leg) and blood flow on right dorsalis pedis artery was measured using duplex ultrasound

while skin temperature changes were monitored using an infrared themographic camera.

RESULTS: Short-term changes in the blood flow parameters, volume flow and average velocity,

compared to baseline (P < 0.05), were observed on MaSP of the lower extremity, ML4. Changes in the

peak systolic velocity of the area ML5 were also observed relative to baseline. The skin temperature of

two different MaSPs on the lateral side of leg (LL4 and LL5) and four on the medial side of leg (ML2,

ML3, ML4 and ML5) was significantly increased (P < 0.05) at 1 min after pressure application.

CONCLUSION: This study established the clear correlation between the location of MaSP, as defined

in CTTM, and the underlying anatomical structures. The effect of massage can stimulate skin blood flow

because results showed increased skin temperature and blood flow characteristics. While these results

were statistically significant, they may not be clinically relevant, as the present study focused on the

immediate physiological effect of manipulation, rather than treatment effects. Thus, this study will serve

as baseline data for further clinical studies in CTTM.

Keywords: complementary therapies; massage; cadaver; blood flow; skin temperature

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60323-6

Received October 25, 2016; accepted December 6, 2016.

Correspondence: Angkana Apichartvorakit. E-mail: angkana.api@mahidol.ac.th

Journal of Integrative Medicine 142 March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

Citation: Viravud Y, Apichartvorakit A, Mutirangura P, Plakornkul V, Roongruangchai J, Vannabhum M,

Laohapand T, Akarasereenont P. The anatomical study of the major signal points of the court-type Thai

traditional massage on legs and their effects on blood flow and skin temperature. J Integr Med. 2017;

15(2): 142–150.

1 Introduction the anatomical and physical effects of CTTM, we have

undertaken a similar study for the lower extremities. The

Massage is the systemic manipulation of the body’s objective of this study is to characterize the correlation of

soft tissue with the purpose of to enhancing health and the underlying anatomical structures with each MaSP. In

promoting healing.[1] Although effects of different types of addition, this study aims to describe and compare the ST

massages are reported in various scientific journals, only and BF changes in the lower extremities when each MaSP

a few pertain to Thai traditional massage. In Thailand, is manipulated.

there are two main types of traditional massages,[2] here

referred to as popular type and court-type. Court-type 2 Materials and methods

Thai traditional massage (CTTM) gets its name from the

traditional discipline reserved for members of the royal 2.1 Study design

court. The main purpose of CTTM is treating ailments, This study was approved by the ethical committee of the

while the popular type is used for relaxation. The CTTM Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University,

technique specifies that only hands and thumbs are used Thailand. There are two parts to the study method (Figure 1).

to massage the body.[3] Despite its origins at court, CTTM The first part relates to the study of anatomical relationship

is currently used widely in Thailand including hospitals, of the MaSPs in the lower extremities using embalmed

primary health care units and district hospitals. The cadavers and is similar to the method described by

application of pressure to the major signal points (MaSPs) Plakornkul et al.[14] The second part of the study relates to

to produce healing or alleviate ailments is at the heart of the measuring BF and ST changes in healthy volunteers.

massage treatment in CTTM.[4] Thai traditional practitioners

believe that MaSP massage can decrease muscle tension,

increase blood and lymphatic circulations and stimulate the

nervous system.[2–4] There are 10 basic massage lines and 50

specific MaSPs distributed throughout the body, including

the extremities, abdomen, head and neck.[3,4]

Studies have shown the clinical efficacy of massage

in relieving pain and muscle tension.[5–8] Specifically, a

randomized controlled trial demonstrated that CTTM was

superior to standard physical therapy in relieving muscle

tension, muscle spasm and increasing functional ability in

stroke patients.[6] Massage has also been shown to affect

blood circulation.[9–11] Chenpanich et al.[12] demonstrated

that CTTM was able to significantly decrease blood

pressure, as well as increase local skin temperature

(ST) in the upper extremities of human volunteers.

Moreover, the ST in the present study was detected by

infrared camera technology, which can reliably localize

changes in ST.[13] An additional study also showed that Figure 1 Study flowchart

even the isolated application of pressure on MaSPs of MaSPs: major signal points.

the neck, shoulder and arm was able to increase blood

circulation significantly.[14] This suggests that MaSPs may 2.2 Participants

have anatomical correlations with muscles and blood 2.2.1 Cadaveric specimens

vessels that mediate the effect of massage on blood flow The sample size needed to demonstrate statistical

(BF), blood volume and ST of the manipulated areas. correlations among MaSPs and anatomical markers was

However, MaSP manipulation of the lower extremities not calculated. Instead, all of the embalmed cadavers

differs substantially from that of the upper extremities intended for the use of medical students during the

in terms of the larger body surface and blood supplies, year 2012–2013, with no evidence of previous injury,

position of the practitioner as well as the force applied. deformity or prior surgery on the lower extremities,

Thus, in order to bridge the knowledge gap and document were included. Cadavers donated to the Department of

March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2 143 Journal of Integrative Medicine

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol

University, Thailand, were from individuals who signed

body donation consent forms prior to their deaths. They

were preserved using standard embalming techniques.

2.2.2 Volunteer subjects

Healthy volunteers (n = 30), comprised of 15 males

and 15 females, were used for ST and BF studies. Sample

size was calculated from a pilot trial showing changes in

mean blood velocity before and after pressure application

of (17.42 ± 28.71) mL/min. Using test significance

level of 0.05, a power = 80% and effect size of 0.607,

the estimated sample size was 24. The same pilot trial

was done measuring ST changes, and showed a mean

difference of (0.69 ± 0.82) °C. Using test significance

level = 0.05, power = 80% and effect size = 0.84, the

calculated sample size was 14. Therefore, in order to

ensure sufficiently significant result, we chose the larger

sample size of 24.

Healthy volunteer subjects were students or staff of the

Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University.

All were required to satisfy the following criteria: (a) aged

18–25 years; (b) body mass index between 18 and 23 kg/m2; Figure 2 The major signal points of the leg on cadaver

(c) exercise < 5 times/week and not an active athlete; Major signal points 1 to 5 on lateral side of leg (MaSP-LL1 to MaSP-

(d) nonsmoker and nonalcoholic; (e) no history of trauma, LL5) and medial side of leg (MaSP-ML1 to MaSP-ML5). A: anterior

view; B: posterior view.

fracture, surgery or arthritis of the lower extremities;

(f) not suffering from skin rash or other dermatological

condition on the lower extremities; (g) not diagnosed with

a communicable disease; (h) no underlying neuropathy,

musculoskeletal or cardiovascular disease; (i) no

history of hypertension or diabetes; (j) not febrile (body

temperature < 38.5 °C); (k) not pregnant or menstruating

(only female). All participants were required to read and

sign informed consent prior to engaging in any study

procedures. The study was performed at the Faculty of

Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand.

2.3 Intervention and measurement

2.3.1 Cadaveric specimens

All cadavers were checked for anatomical intactness. Then

map pins were used to mark the MaSPs 1 to 5 on lateral side

of the leg (MaSP-LL1 to MaSP-LL5) and the medial side

of the leg (MaSP-ML1 to MaSP-ML5) by three licensed

applied Thai traditional medical (ATM) practitioners, who

Figure 3 Instruments used for studying on cadaveric specimens

were experts in CTTM from the Center of Applied Thai A: pin (18.0 inches × 1.5 inches); B: map pins; C: ring diameter 1 inch

Traditional Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, or 1.5 inches; D: hypodermic syringe; E: instrument for dissection.

Mahidol University, Thailand. The pin placement was agreed

upon by the 3 practitioners before the experiment in order to 2.3.2 Volunteer subjects

minimize variability among practitioners. Subsequently, pin The locations of 10 MaSPs are shown in Figure 4 on one

locations were injected with acrylic color, using a hypodermic of the volunteers. Pressure application to all MaSPs was

syringe (18.0 inches × 1.5 inches). Figure 2 illustrates the performed by a single practitioner, who also participated

underlying anatomical locations of MaSPs, as marked by in the cadaver experiment. As specified by CTTM

pins. Correlations between acrylic markers and the underlying technique, both thumbs were used to apply pressure in

anatomical structures were determined after the cadavers had 3 stages, initiation, accentuation and steady, on each

been dissected by medical students. Areas marked with acrylic MaSP, over a 30-second period.[2,3] After 30 s of applying

colors were observed using a circular ring with a diameter of pressure on each MaSP, the thumbs were released from

1 inch or 1.5 inches as illustrated in Figure 3. the point and the measurements were performed.

Journal of Integrative Medicine 144 March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

BF studies on volunteers were performed at the

Division of Vascular Surgery Unit, Faculty of Medicine

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. An

ATM practitioner massaged the MaSP-ML1 to -ML5

(Figure 4), while a technician measured BF continuously,

from before MaSP manipulation to 5 min after completion

of the massage, using an ultrasound machine designed

to make precise BF measurements (LOG IQ E9; GE

Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis., USA). Using a digital

mobile sphygmomanometer on the left arm, two sets

of blood pressure and heart rate measurements were

taken: one after a 15-minute rest period before pressure

application, and a second after the completion of all 5

MaSP manipulations.

Blood volume, velocity and the vessel diameter

measurements were conducted on the left dorsalis pedis

artery (Figure 5). Only the 5 MaSPs which corresponded

to the arteries of the lower extremities were used when

measuring BF. The blood volume was automatically

calculated by using vessel diameter. Because a previously

performed pilot study determined that BF and ST effects

were not observable after 5 min, we rationalized that

our measurements should occur at baseline (T baseline),

immediately after pressure release (T 1), 1 min after

pressure release (T2), 3 min after pressure release (T3) and

5 min after pressure release (T4) for each MaSP. A 5-minute

rest period was observed before applying pressure to the

next MaSP.

ST was recorded by a infrared thermographic camera

(TVS-500; Nippon Avionics, Japan). ST of MaSP-ML2 Figure 4 The major signal points of the leg on human

A: major signal points 1 to 5 on medial side of leg (MaSP-ML1 to

to ML5 and MaSP-LL4 and MaSP-LL5 was measured MaSP-ML5); B: major signal points 1 to 5 on lateral side of leg (MaSP-

after manipulation by the ATM practitioner. Nonetheless, LL1 to MaSP-LL5).

the ST of MaSP-ML1, MaSP-LL1, MaSP-LL2 and

MaSP-LL3 was not shown due to the subjects clothing.

The room was controlled for illumination and kept at a

constant temperature of 25 ºC. Thermography Studio 2007

(version 4.8) was used to extract temperatures from the

thermal images. Tympanic temperature of the participants

was measured after a 15-minute resting period and before

the experiment began. The STs were measured at Tbaseline,

T1, T2, T3 and T4. A 5-minute rest period was observed

before applying pressure to the next MaSP.

2.4 Statistical analysis

SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc, Version 18.0; Chicago,

IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. Descriptive

data includes percent of anatomical correlation to each

MaSP. Volume and mean velocity of BF were tested

after natural logarithm transformation because data were

not normally distributed. Two-way repeated measures

analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s method for

adjusted multiple comparisons was used to compare the

Figure 5 Measurement of blood flow before and after pressure

changing volume and velocity of BF, diameter of left application at baseline (T baseline), immediately after pressure

dorsalis pedis and ST in each of the MaSP. These values release (T1), 1 min after pressure release (T2) and 5 min after

were compared to baseline. pressure release (T4) on the MaSP-ML3 at dorsalis pedis artery

March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2 145 Journal of Integrative Medicine

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

3 Results The median age was 72 years (range 21–99 years). A high

degree of anatomical correlation was observed for most

3.1 Cadaveric specimens MaSPs, except for MaSP-ML1–ML2, where 2 adjacent

A total of 84 embalmed cadavers (32 females and 52 muscles were identified. Detailed correlation data can be

males) were included in this study, out of the 88 available. found in Table 1.

Table 1 Anatomical relation on major signal points on lateral side of leg (MaSP-LL1 to MaSP-LL5) and medial side of leg (MaSP-

ML1 to MaSP-ML5) (N = 84)

Structure MaSP-LL1 MaSP-LL2 MaSP-LL3 MaSP-LL4 MaSP-LL5

Subcutaneous Subcostal cutaneous Subcostal cutaneous Dorsal rami L1–L3 Lateral cutaneous nerve of Lateral sural

nerve (100%) nerve (100%) (100%) thigh (100%) cutaneous nerve

(100%)

Muscle Gluteus medius Iliotibial tract Gluteus maximus Iliotibial tract (100%) Crural fascia (100%)

(100%) (100%) (100%) Vastus lateralis (100%) Peroneus longus

Gluteus minimus Tensor fascia latae Pirifomis (100%) Vastus intermedius (100%) (100%)

(100%) (100%) Superior and inferior

Gluteus medius gemellus (77.38%)

(100%) Obturator internus

(77.38%)

Vessel Superior gluteal

artery (98.81%)

Nerve Superior gluteal Superficial peroneal

(98.81%) (100%)

Bone Ilium part of pelvic Ilium part of pelvic Ischium part of Lateral side of femur Fibular bone (100%)

(100%) (100%) pelvic, capsular (100%)

ligament of hip joint

and neck of femur

(100%)

Structure MaSP-ML1 MaSP-ML2 MaSP-ML3 MaSP-ML4 MaSP-ML5

Subcutaneous Posterior cutaneous Cutaneous branch Med. cutaneous Posterior cutaneous nerve Saphenous nerve

nerve of thigh of obturator nerve nerve of thigh of thigh (100%) (100%)

(100%) (100%) (100%)

Muscle Semitendinosus Gracilis (100%) Vastus medialis Popliteal fascia (100%) Flexor retinaculum

(100%) Adductor magnus (100%) (100%)

Semimembranosus (82.14%) Flexor halluces

(100%) Adductor longus longus (100%)

Biceps femoris (long (47.61%)

head) (100%) Vastus medialis

Adductor maximus (100%)

(ham part) (52.38%)

Vessel Femoral vessel Femoral vessel Popliteal vessel (100%) Posterior tibial

(100%) (Adductor canal) artery (100%)

(85.71%)

Descending genicular

artery (100%)

Nerve Anterior branch Nerve to Tibial nerve (100%) Tibial nerve or

of obturator nerve vastusmedialis medial and lateral

(100%) (76.19%) plantar nerve (100%)

Posterior branch Saphenous nerve

of obturator nerve (Adductor canal)

(82.14%) (100%)

Saphenous nerve

(100%)

Bone Shaft of femur Shaft of femur Shaft of femur Popliteal surface of femur Talus bone (100%)

(100%) (100%) (100%) (100%)

Journal of Integrative Medicine 146 March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

3.2 Volunteer subjects ML5 exceeded their baseline values. The vessel diameter

Thirty volunteer subjects (15 male and 15 female) were showed no statistically significant changes (Figure 6).

enrolled in this study. The demographic data and physical ST of MaSPs significantly increased immediately after

characteristic of participants are shown in Table 2. pressure application (0.2–0.4 °C on the MaSP-LL4 and

MaSP-LL5 and 0.2–0.7 °C on the MaSP-ML2 through

Table 2 Physical characteristics of participants MaSP-ML5). ST on the MaSP-ML4 appeared as changed

skin color in the thermal images, as seen in Figure 7. The

Values

Factor N color of area 1 in Figure 7B, C, D and E revealed higher

Mean Standard deviation temperature than that was present in Figure 7A. ST on

Age (year) 30 22.20 2.02 MaSP-ML2 through ML5 and MaSP-LL4 and LL5 slowly

decreased, but remained higher than baseline at 5 min after

Weight (kg) 30 57.97 7.11

pressure release (Figure 8).

Height (cm) 30 166.50 6.89

Body mass index (kg/m2) 30 20.98 1.94 4 Discussion

Systolic pressure (mmHg) 30 106.10 8.96

Diastolic pressure (mmHg) 30 59.77 8.34 This study is the first to report both the anatomical

correlation of MaSP and the effects of MaSP massage

Heart rate (beat/min) 30 72.43 11.34

on BF and ST in the lower extremities. Such correlation

Temperature (°C) 30 36.73 0.47 helps substantiate the traditional belief that pressure on

the MaSP can affect nerves and control the distribution of

The volume and velocity of BF showed a similar blood and heat to parts of the body.[2]

pattern of change for all MaSPs: both values decreased The fluctuation in BF of ML1-5 at different time points

with pressure application and increased immediately after confirms the effect of MaSP manipulation on circulation.

pressure release (Figure 5). However, both volume and In our study, we measured BF from the dorsalis pedis

velocity of BF at MaSP-ML1 and -ML2 did not return artery, which is the terminal branch of femoral artery.

to baseline values, while MaSP-ML3 through MsSP- Therefore, applying pressure on the MaSP proximal

Figure 6 Changes in blood flow of the dorsalis pedis which correspond to the major signal points on medial side of leg (MaSP-ML1

to ML5) in each point compared with baseline (N = 30)

A: volume flow (antilogarithm of mean and standard deviation); B: average mean velocity (antilogarithm of mean and standard deviation); C:

diameter of dorsalis pedis; D: peak systolic velocity.

Statistical significant at P < 0.05 compared with Tbaseline on MaSP-ML1 (*), MaSP-ML2 (△), MaSP-ML3 (▲), MaSP-ML4 (□), and MaSP-ML5 (■).

March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2 147 Journal of Integrative Medicine

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

Figure 7 Infrared thermography image of skin temperature at Figure 8 Changes in skin temperture on the major signal points

major signal point on medial side of left leg in each point compared with baseline (N = 30)

Area 1 represent the area of the MaSP-ML4. (A) Tbaseline, (B) T1, (C) T2, A: The major signal points on medial side of leg (MaSP-ML2 to ML5);

(D) T3, and (E) T4. B: The major signal points on lateral side of leg (MaSP-LL4 and -LL5).

Statistical significant at P < 0.05 compared with Tbaseline on MaSP-ML2

to the dorsalis pedis artery can cause BF alteration. ( ), MaSP-ML3 (▲), MaSP-ML4 (□), MaSP-ML5 (■), MaSP-LL4 (†),

By taking into account the ambient temperature, [15] and MaSP-LL5 (#).

circadian rhythm and time of day, this study attempts

to control for factors which can affect body and ST.[16] measurements impossible. On the other hand, measuring

Other published literature also confirmed the effect of BF changes at the most distal positions reaffirms CTTM’s

massage on ST. Drust et al. [17] examined the effect of theory that manipulation of MaSPs should lead to

massage and ultrasound on intramuscular temperature in improved BF distal to the points of manipulation.

the vastus lateralis muscle in humans. Changes in muscle In this study, MaSP-ML2 is shown to be near the

temperature at 1.5 and 2.5 cm were significantly greater femoral artery, while MaSP-ML4 corresponds to the

following massage than following ultrasound (P < 0.002). location of the popliteal artery. CTTM indicates that

Chenpanich et al. [12] studied Thai traditional massage these MaSPs are among the key points for treatment of

and showed that an increase in temperature occur red in lower back pain and diseases related to the lower

both feet even though only the right leg was massaged. extremities. [4] However, it is worth noting that the normal

Although using different massage protocols, these results CTTM protocol usually involves massages that cover

still illustrated the effect of massage on increasing ST. both the basic and the specific MaSPs. Thus, when each

Higher changes in ST observed in our study are attributed of these MaSPs is manipulated separately, the results may

to the fact that MaSPs located on the ML are correlated differ from the protocol followed in the present study.

with blood vessels and yield higher ST, while points on Therefore, further studies of ST and BF changes within

the lateral side are not. These observed changes in STs the context of the complete CTTM treatment protocol are

are related to study duration. To ascertain the true effect needed in order to establish their true clinical significance.

of MaSP pressure in future studies, as well as mimic Results from a similar study of BF and ST changes

CTTM practice, basic massage maneuvers should be after MaSP manipulation of the upper extremities found

added before MaSP pressures are done. Although most that both parameters changed in a pattern similar to the

BF studies by Doppler ultrasound reporting Vmax, Vmean and present work.[14] Their work showed that ST increased

BF use the femoral artery,[18–20] this study uses the dorsalis immediately after pressure application on the MaSP and

pedis instead. This is because CTTM position requires then slowly decreased. MaSPs which were supplied by the

that the patient lies on his side, making femoral artery brachial and radial arteries had significant and sustained

Journal of Integrative Medicine 148 March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

BF changes during the first 30s of pressure. On the 8 Conflict of interest

contrary, similarly located MaSPs of the lower extremities

in our study showed much more sustained BF changes. The authors declare that there is not any conflict of

In addition, manipulation of the laterally located MaSPs interests.

of the upper extremity corresponded with significant

changes in STs of all areas, while medially located MaSPs REFERENCES

resulted in only 2 areas of ST changes.[14] In contrast,

our study found significant changes in STs for both 1 Patricia JB, Frances MT. Tappan’s handbook of healing

medially and laterally located MaSPs of the leg. Over massage techniques; classic, holistic and emerging

all, MaSP manipulation resulted in similar patterns of ST methods. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education

and BF changes in both the upper and lower extremities. Inc. 2005: 4–7.

However, the degree of changes in ST was much more 2 Laohapand T, Jaturatamrong U. Thai traditional medicine

pronounced in the lower extremities. Regardless, these in the faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital. Bangkok:

Supavanich Press. 2009: 21–23.

findings reaffirmed the belief that MaSP manipulation

3 Laohapand T, Jaturatamrong U. Thai traditional massage

results in increased distribution of blood and warmth to (The court-type Thai traditional massage): basic massage

distal areas, and that is the heart of CTTM practice. line. 2nd ed. Bangkok: Supavanich Press. 2011: 18–23.

The anatomical study of the MaSP on cadavers has 4 Laohapand T, Jaturatamrong U. Thai traditional massage

many limitations associated with the morphology of (The court-type Thai traditional massage): the signal point

cadavers and indistinct surface marking. However, the massage. 2nd ed. Bangkok: Supavanich Press. 2014: 99–

use of more experienced ATM practitioners can minimize 104. Thai.

errors. In addition, the wide age range of the cadavers 5 B u t t a g a t V, E u n g p i n i c h p o n g W, C h a t c h a w a n U ,

may affect their anatomical landmarks and anatomical Arayawichanon P. Therapeutic effects of traditional Thai

massage on pain, muscle tension and anxiety in patients

variations among individual cadavers.

with scapulocostal syndrome: a randomized single-blinded

pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012; 16(1): 57–63.

5 Conclusions 6 Buttagat V, Eungpinichpong W, Chatchawan U, Kharmwan

S. The immediate effects of traditional Thai massage

This study establishes the clear association between on heart rate variability and stress-related parameters in

MaSPs, as defined in CTTM, and the underlying patients with back pain associated with myofascial trigger

anatomical structures. Validation of CTTM techniques points. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011; 15(1): 15–23.

using measurable outcomes, such as landmarks, ST and 7 Buttagat V, Eungpinichpong W, Kaber D, Chatchawan U,

Arayawichanon P. Acute effects of traditional Thai massage

BF changes, helps to document and validate traditional on electroencephalogram in patients with scapulocostal

knowledge. This will serve as baseline data for further syndrome. Complement Ther Med. 2012; 20(4): 167–174.

clinical studies of CTTM to confirm the traditional CTTM 8 Thanakiatpinyo T, Suwannatrai S, Suwannatrai U,

theory. Khumkaew P, Wiwattamongkol D, Vannabhum M,

Pianmanakit S, Kuptniratsaikul V. The efficacy of traditional

6 Funding Thai massage in decreasing spasticity in elderly stroke

patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2014; 11(9): 1311–1319.

This study was supported by the Siriraj Research Fund 9 Cambron JA, Dexheimer J, Coe P. Changes in blood

pressure after various forms of therapeutic massage: a

(No. R015631018).

preliminary study. J Altern Complement Med. 2006; 12(1):

65–70.

7 Acknowledgments 10 Kaye AD, Swinford J, Baluch A, Bawcom BA, Lambert JT,

Hoover JM. The effect of deep-tissue massage therapy on

The authors would thank all volunteer subjects blood pressure and heart rate. J Altern Complement Med.

and be very grateful to the Department of Anatomy, 2008; 14(2): 125–128.

the Division of Vascular Surgery and the Centre of 11 Fielda T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M. Massage therapy

the Applied Thai Traditional Medicine, Faculty of research. Dev Rev. 2007; 27(1): 75–89.

Medicine Siriraj Hospital. In addition, our special 12 Chenpanich K, Tuchinda P. Effect of Thai traditional

massage on the circulatory system. Siriraj Hosp Gaz. 1981;

thanks are directed to Mr. Supakij Su wannatrai,

33(9): 575–581. Thai.

Mrs. Ueamphon Suwannatrai, and Mr. Somporn 13 Jones BF. A reappraisal of the use of infrared thermal image

Nongbuadee who are expert in the CTTM from the analysis in medicine. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;

Center of Applied Thai Traditional Medicine for 17(6): 1019–1027.

devoting their time to the study, to Miss Pimrapat 14 Plakornkul V, Vannabhum M, Viravud Y, Roongruangchai J,

Tengtrakulcharoen for statistical advice, and to Miss Mutirangura P, Akarasereenont P, Laohapand T. The effects

Suksalin Booranasubkajorn and Assoc. Prof. Chulatida of the court-type Thai traditional massage on anatomical

Chomchai for proofreading the article. relations, BF, and ST of the neck, shoulder, and arm. BMC

March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2 149 Journal of Integrative Medicine

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

Complement Altern Med. 2016; 16: 363. Acute peripheral BF response induced by passive leg cycle

15 Silbernagl S, Despopoulos A. Color atlas of physiology. 6th exercise in people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med

ed. New York: Thieme Publishing Group. 2009: 224–225. Rehabil. 2007; 88(4): 471–476.

16 Rhoades RA, Bell DR. Medical physiology principles for 19 Dinenno FA, Jones PP, Seals DR, Tanaka H. Limb BF

clinical medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & and vascular conductance are reduced with age in healthy

Williams. 2013: 563–564. humans: relation to elevations in sympathetic nerve activity

17 Drust B, Atkinson G, Gregson W, French D, Binningsley D. and declines in oxygen demand. Circulation. 1999; 100(2):

The effects of massage on intra muscular temperature in the 164–170.

vastus lateralis in humans. Int J Sports Med. 2003; 24(6): 20 Hinds T, Mcewan I, Prkes J, Dawson E, Ball D, George K.

395–399. Effects of massage on limb and skin BF after quadriceps

18 Ballaz L, Fusco N, Crétual A, Langella B, Brissot R. exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004; 36(8): 1308–1313.

Submission Guide

Journal of Integrative Medicine (JIM) is an international, types include reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses,

peer-reviewed, PubMed-indexed journal, publishing papers randomized controlled and pragmatic trials, translational and

on all aspects of integrative medicine, such as acupuncture patient-centered effectiveness outcome studies, case series and

and traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, herbal reports, clinical trial protocols, preclinical and basic science

medicine, homeopathy, nutrition, chiropractic, mind-body studies, papers on methodology and CAM history or education,

medicine, Taichi, Qigong, meditation, and any other modalities editorials, global views, commentaries, short communications,

of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Article book reviews, conference proceedings, and letters to the editor.

● No submission and page charges ● Quick decision and online first publication

For information on manuscript preparation and submission, please visit JIM website. Send your postal address by e-mail to

jcim@163.com, we will send you a complimentary print issue upon receipt.

Journal of Integrative Medicine 150 March 2017, Vol. 15, No. 2

You might also like

- CBMT and NTDocument11 pagesCBMT and NTrizkiriasariNo ratings yet

- Effecthiparthroplasy 2012Document10 pagesEffecthiparthroplasy 2012JESSICA OQUENDO OROZCONo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy in The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Diabetic Patients: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument7 pagesManual Therapy in The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Diabetic Patients: A Randomized Clinical TrialHerwanda PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Blood Flow Volume As An Indicator of The Effectiveness of Traditional MedicineDocument26 pagesBlood Flow Volume As An Indicator of The Effectiveness of Traditional Medicineluz_1No ratings yet

- Reliability and Efficacy of The New Massage TechniDocument10 pagesReliability and Efficacy of The New Massage TechniPeter DamienNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Rehabilitation: Interventions and Outcomes 631: ROC Curve For The Cut-Off Value of 6MWDDocument1 pageCardiac Rehabilitation: Interventions and Outcomes 631: ROC Curve For The Cut-Off Value of 6MWDKings AndrewNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Kinesiologic Tape Application in Rotator Cuff InjuriesDocument6 pagesEffectiveness of Kinesiologic Tape Application in Rotator Cuff InjuriesdarisNo ratings yet

- Abstract 13 PDFDocument1 pageAbstract 13 PDFIJMAESNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Arthro 2019 06 017Document17 pages10 1016@j Arthro 2019 06 017Ines Riera MoyaNo ratings yet

- Efek Deep MassageDocument5 pagesEfek Deep MassageAsmawati NadhyraNo ratings yet

- Bmri2022 4133883Document8 pagesBmri2022 4133883aaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper 1Document14 pagesResearch Paper 1Ayesha HabibNo ratings yet

- I C M M, M O, H P A M T P - F H P: A R C TDocument9 pagesI C M M, M O, H P A M T P - F H P: A R C TAngie D. AndradesNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Muscle Energy Technique On HeadacheDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Muscle Energy Technique On HeadacheDavid FehertyNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Medicine: Kıymet Muammer, Fatma Mutluay, Rengin Demir, Alev Arat OzkanDocument10 pagesRespiratory Medicine: Kıymet Muammer, Fatma Mutluay, Rengin Demir, Alev Arat OzkanMalik JamilNo ratings yet

- Dunning James Et AlDocument10 pagesDunning James Et Alapi-290796947No ratings yet

- Cjim 11 163Document8 pagesCjim 11 163Nurul Annisa KamalNo ratings yet

- Seifert 2018Document12 pagesSeifert 2018Hải TrầnNo ratings yet

- MMT Validity ReliabilityDocument23 pagesMMT Validity ReliabilitynNo ratings yet

- Dry Needling Versus Trigger Point Injection For Neck PainDocument11 pagesDry Needling Versus Trigger Point Injection For Neck PainDavid ElirazNo ratings yet

- Articulo BrasileroDocument8 pagesArticulo BrasileroLuis GalvanNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Foot Reflexology On Blood Pressure and Heart Rate: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Stage-2 Hypertensive PatientsDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Foot Reflexology On Blood Pressure and Heart Rate: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Stage-2 Hypertensive PatientsNurul AidaNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.09.015Document10 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.09.015Daniel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 10 1093@pm@pny278Document15 pages10 1093@pm@pny278Anthony VillafañeNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Exercises in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument20 pagesThe Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Exercises in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisBruno FellipeNo ratings yet

- Journal ESWT Pada DewasaDocument7 pagesJournal ESWT Pada DewasaPhilipusHendryHartonoNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Mesotherapy On Body Contouring: BackgroundDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Mesotherapy On Body Contouring: BackgroundNita Dewi NNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Muscle Energy TechniquesDocument18 pagesThe Efficacy of Muscle Energy Techniquesmuhammad yaminNo ratings yet

- Journal M 10Document4 pagesJournal M 10Pit PitoyoNo ratings yet

- 1 - 2017 - Tuina para Prob Musculo-Esqueléticos - Rev SistDocument22 pages1 - 2017 - Tuina para Prob Musculo-Esqueléticos - Rev SistLuis Miguel MartinsNo ratings yet

- Inspiratory Muscle Training Lowers BP More Than Slow Deep BreathingDocument7 pagesInspiratory Muscle Training Lowers BP More Than Slow Deep BreathingannaNo ratings yet

- Sridevi 3347 B2021 JPRI74445Document8 pagesSridevi 3347 B2021 JPRI74445Shree PatelNo ratings yet

- Alp Tekin 2016Document6 pagesAlp Tekin 2016Anisah Imansari RahayuNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Exercise Therapy On Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Exercise Therapy On Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialElva Diany SyamsudinNo ratings yet

- Bab 2Document2 pagesBab 2SANDA NABILAH FATINNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Therapy in Musculoskeletal Medicine (4939)Document9 pagesIschemic Therapy in Musculoskeletal Medicine (4939)RexDavidGidoNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Lori A. Michener, Joseph R. Kardouni, Catarina O. Sousa, Jacqueline M. ElyDocument5 pagesManual Therapy: Lori A. Michener, Joseph R. Kardouni, Catarina O. Sousa, Jacqueline M. Elyubiktrash1492No ratings yet

- LaserDocument8 pagesLaserALİ YAVUZ KARAHANNo ratings yet

- Efectividad de La Fisio en EspasticidadDocument58 pagesEfectividad de La Fisio en EspasticidadAbner SánchezNo ratings yet

- Terapi HT PDFDocument9 pagesTerapi HT PDFHamdaniNo ratings yet

- Conservative Management of Mechanical NeDocument20 pagesConservative Management of Mechanical NeVladislav KotovNo ratings yet

- Benefits of High-Intensity Exercise Training To Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Controlled StudyDocument10 pagesBenefits of High-Intensity Exercise Training To Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Controlled StudyCésarNo ratings yet

- Effect of Massage Therapy On PDocument7 pagesEffect of Massage Therapy On PVicky ImanNo ratings yet

- JCM 11 00950Document11 pagesJCM 11 00950Ligia BoazuNo ratings yet

- Free Paper Presentations0000Document94 pagesFree Paper Presentations0000Syed Imroz KhanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Electroacupuncture and Body Acupuncture on Gastrocnemius Muscle Tone in Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Single Blinded, Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialDocument6 pagesComparison of Electroacupuncture and Body Acupuncture on Gastrocnemius Muscle Tone in Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Single Blinded, Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialrezteevicNo ratings yet

- Sanjana S. Zad, Pragati PatilDocument15 pagesSanjana S. Zad, Pragati PatilAquaNo ratings yet

- 2012 Article 220Document5 pages2012 Article 220Ines Riera MoyaNo ratings yet

- Medscimonit 20 1833Document8 pagesMedscimonit 20 1833Snezana DjukicNo ratings yet

- Effects of Kinesiotherapy, Ultrasound and Electrotherapy in Management of Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis: Prospective Clinical TrialDocument10 pagesEffects of Kinesiotherapy, Ultrasound and Electrotherapy in Management of Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis: Prospective Clinical TrialDavid Alejandro Cavieres AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Tui Na Musculo IsocineticoDocument7 pagesTui Na Musculo IsocineticoCristian Dionisio Barros OsorioNo ratings yet

- Could Forearm Kinesio Taping Improve StrengthDocument7 pagesCould Forearm Kinesio Taping Improve StrengthFelix LoaizaNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Ultrasound Treatment For The Management of KDocument7 pagesThe Effectiveness of Ultrasound Treatment For The Management of Kkrishnamunirajulu1028No ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument9 pagesResearch ArticlesoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Yuksel2020, Effect of Cuffsize in BP MeasurementDocument8 pagesYuksel2020, Effect of Cuffsize in BP MeasurementMumtaz MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of CarpalDocument7 pagesPrevalence of CarpalAnis AmmarNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Guided Musculoskeletal Procedures in Sports Medicine: A Practical AtlasFrom EverandUltrasound Guided Musculoskeletal Procedures in Sports Medicine: A Practical AtlasRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Pengaruh Pemberian Ischemic Compression Dan Contract Relax Stretching Terhadap Intensitas Nyeri Myofascial Trigger Point Syndrome Ototupper TrapeziusDocument9 pagesPengaruh Pemberian Ischemic Compression Dan Contract Relax Stretching Terhadap Intensitas Nyeri Myofascial Trigger Point Syndrome Ototupper TrapeziusDian DianaNo ratings yet

- Andrew IJTRRDocument8 pagesAndrew IJTRRsiddharthaNo ratings yet

- Branches of PsychologyDocument2 pagesBranches of Psychologyanandi rayNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonographic Diagnosis of Pregnancy in Dogs and CatsDocument8 pagesUltrasonographic Diagnosis of Pregnancy in Dogs and CatsAnur SinglaNo ratings yet

- Face BowDocument15 pagesFace Bowalosh60No ratings yet

- Prosthodontics (Fixed Partial Denture)Document17 pagesProsthodontics (Fixed Partial Denture)David SarnoNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics of The Osteoperotic SpineDocument8 pagesBiomechanics of The Osteoperotic SpineIsmael Vara CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- ACCUVAC Lite 83150-EN PDFDocument8 pagesACCUVAC Lite 83150-EN PDFalonso7878No ratings yet

- Chapple Et Al-2017-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyDocument13 pagesChapple Et Al-2017-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyJulio César PlataNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For HAADDocument7 pagesSyllabus For HAADvirasamir100% (2)

- Exposure Chart Mobile X Ray PDFDocument8 pagesExposure Chart Mobile X Ray PDFlutfiaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Aspects of Alzheimer Disease: Thomas D. Bird, MDDocument9 pagesGenetic Aspects of Alzheimer Disease: Thomas D. Bird, MDandrea lopezNo ratings yet

- MTF Surgery KitDocument33 pagesMTF Surgery KitCarolyn Samuels75% (4)

- Naskah IschialgiaDocument9 pagesNaskah IschialgiaPuspo Wardoyo100% (1)

- CryoglobulinsDocument39 pagesCryoglobulinsanamariavNo ratings yet

- Leisegang LM 900 BrochureDocument2 pagesLeisegang LM 900 BrochureFrancisco Javier Millan ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Pacop Violet Pharmaceutical ChemistryDocument70 pagesPacop Violet Pharmaceutical ChemistryAstherielle GalvezNo ratings yet

- Venture l1 Unit 12 RecuperoDocument2 pagesVenture l1 Unit 12 RecuperoMichele SellittoNo ratings yet

- Ucsp Handouts Religion - HealthDocument11 pagesUcsp Handouts Religion - HealthChristopher Flor de LisNo ratings yet

- Why Does My Patient Limphadenopathy or Splenomegaly?Document14 pagesWhy Does My Patient Limphadenopathy or Splenomegaly?lacmftcNo ratings yet

- Imagine Having Autism - Richard EisenmajerDocument2 pagesImagine Having Autism - Richard Eisenmajerapi-237515534No ratings yet

- Biological Treatments in PsychiatryDocument56 pagesBiological Treatments in PsychiatryNurul AfzaNo ratings yet

- IMMULITE:IMMULITE 1000 Toxoplasma Quantitative IgGDocument41 pagesIMMULITE:IMMULITE 1000 Toxoplasma Quantitative IgGsauco786476No ratings yet

- Breath of FireDocument3 pagesBreath of FirepraveenmspkNo ratings yet

- Doctors contact list with qualificationsDocument90 pagesDoctors contact list with qualificationsKriti Kumari78% (9)

- Antiobesity Potential of Gavedhuka (Coix Lacryma Jobi. L.)Document10 pagesAntiobesity Potential of Gavedhuka (Coix Lacryma Jobi. L.)gyan chandNo ratings yet

- Acute Cholecystitis - Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and DiagnosisDocument25 pagesAcute Cholecystitis - Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Diagnosisshita febrianaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Efficacy & Safety of Iron Polymaltose Complex & Ferrous Ascorbate With Ferrous Sulphate in Pregnant Women With Iron-Deficiency AnaemiaDocument7 pagesComparison of Efficacy & Safety of Iron Polymaltose Complex & Ferrous Ascorbate With Ferrous Sulphate in Pregnant Women With Iron-Deficiency AnaemiaNimesh ModiNo ratings yet

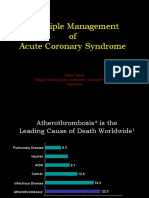

- Principle Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Nahar Taufiq Bagian Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskuler FK UGM YogyakartaDocument57 pagesPrinciple Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Nahar Taufiq Bagian Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskuler FK UGM YogyakartaIntan Farida YasminNo ratings yet

- Uganda Universities and Courses For Student Loan SupportDocument5 pagesUganda Universities and Courses For Student Loan SupportThe Campus TimesNo ratings yet

- 2009 Annual ReportDocument12 pages2009 Annual ReportWSCFoundationNo ratings yet

- Zoheir Aissaoui Rals03-10016Document1 pageZoheir Aissaoui Rals03-10016babelfirdaousNo ratings yet