Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diagnóstico Clínico de La Artritis de La Articulación Temporomandibular PDF

Diagnóstico Clínico de La Artritis de La Articulación Temporomandibular PDF

Uploaded by

Nathaly Granda ZapataOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Diagnóstico Clínico de La Artritis de La Articulación Temporomandibular PDF

Diagnóstico Clínico de La Artritis de La Articulación Temporomandibular PDF

Uploaded by

Nathaly Granda ZapataCopyright:

Available Formats

DR.

MARIA PIGG (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-7989-1541)

Accepted Article

Article type : Original Article

Clinical diagnosis of temporomandibular joint arthritis

Running title: Clinical diagnosis of TMJ arthritis

Category: Original research article

Per Alstergren1, 2, 3, 4, Maria Pigg1, 5 and Sigvard Kopp4

1Scandinavian Center for Orofacial Neurosciences (SCON), Malmö, Sweden;

2Skåne University Hospital, Specialized Pain Rehabilitation, Lund, Sweden;

3Malmö University, Faculty of Odontology, Orofacial Pain Unit, Malmö, Sweden;

4Karolinska Institutet, Department of Dental Medicine, Section for Orofacial Pain and Jaw

Function, Huddinge, Sweden;

5Malmö University, Faculty of Odontology, Department of Endodontics, Malmö, Sweden

Correspondence

Dr. M. Pigg

Malmö University

Faculty of Odontology

Department of Endodontics

SE-205 06 Malmö

Sweden

Email: maria.pigg@mau.se

Abstract

Background

Evidence-based clinical diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis are not

available.

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not

been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may

lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as

doi: 10.1111/joor.12611

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Objective

To establish (i) criteria for clinical diagnosis of TMJ arthritis and (ii) clinical variables useful to

Accepted Article

determine inflammatory activity in TMJ arthritis using synovial fluid levels of inflammatory

mediators as the reference standard.

Methods

A calibrated examiner assessed TMJ pain, function, noise and occlusal changes in 219 TMJs (141

patients, 15 healthy individuals). TMJ synovial fluid samples were obtained with a push-pull

technique using the hydroxycobalamin method and analyzed for TNF, TNFsRII, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-

1sRII, IL-6 and serotonin. If any inflammatory mediator concentration exceeded normal, the

TMJ was considered as arthritic.

Results

In the patient group, 71% of the joints were arthritic. Of those, 93% were painful. 66% of the

non-arthritic TMJs were painful to some degree.

Intensity of TMJ resting pain and TMJ maximum opening pain, number of jaw movements

causing TMJ pain and laterotrusive movement to the contralateral side significantly explained

presence of arthritis (AUC 0.72, p<0.001). Based on these findings, criteria for possible,

probable and definite TMJ arthritis were determined.

Arthritic TMJs with high inflammatory activity showed higher pain intensity on maximum

mouth opening (p<0.001) and higher number of painful mandibular movements (p=0.004) than

TMJs with low inflammatory activity.

Conclusion

The combination TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening and Contralateral laterotrusion <8mm

appears to have diagnostic value for TMJ arthritis. Among arthritic TMJs, higher TMJ pain

intensity on maximum mouth opening and number of mandibular movements causing TMJ pain

indicates higher inflammatory activity.

Key words: Arthritis, Diagnosis, Pain, Synovial fluid, Temporomandibular joint

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Background

Arthritis, i.e. articular tissue inflammation, in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a disorder

Accepted Article

due to either local or systemic factors. Examples of local factors are micro- or macrotrauma

secondary to disc displacement or degenerative joint disease and infection (1, 2). Systemic

factors may be systemic inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic

arthritis (PsA) or reactive arthritis. Clinically, TMJ arthritis may present with articular pain and

pain in adjacent structures and reduced jaw mobility. Cartilage and bone tissue destruction may

result in occlusal changes (loss of anterior contacts between the upper and lower jaw) with

impaired chewing (function) and if present in children and adolescents, mandibular growth

arrest that may lead to micrognathia (3-6).

Inflammation is a complex, rapid, first-line and highly unspecific immune system response with

the purpose to locate and eliminate pathogens and injured tissue as well as to promote tissue

healing. This reaction has a clear and important biologic purpose in the acute phase but may

transfer into a chronic state with very unclear, if any, biologic purpose. The unspecific nature of

the response means that regardless of cause, the reaction involves to a great extent the same

cells, mediators, enzymes etc. The same inflammatory mediators are therefore most likely

involved in local and systemic TMJ arthritis (7), whereas the local concentrations of these

mediators as well as the specific composition may differ. Autoantibodies and autoinflammation

may also contribute to maintenance of the chronic inflammation (8).

Since ancient times, inflammation has clinically been described and diagnosed by the presence

of the five cardinal signs swelling, redness, warmth, pain and impaired function. This is

sometimes adequate regarding acute inflammatory conditions such as pericoronitis and sun-

burned skin. However, for chronic inflammation as well as for many other acute inflammatory

states, these cardinal signs are neither sufficient nor correct to describe, diagnose or monitor

the inflammatory activity. These classical clinical signs may be found in some sites with chronic

inflammation at a certain time-point but in other sites they may be absent. For example, chronic

periodontitis seldom displays any of the cardinal signs despite there being an ongoing

inflammatory process, local immune system activation and disease progression. In the case of

TMJ arthritis, ongoing and progressive chronic TMJ inflammation causing tissue degradation

and/or growth disturbance may also be pain-free for substantial periods. At a given time point,

the clinical presentation may be anywhere on a continuum from no sign or symptom

whatsoever to any combination of pain, swelling/exudate, tissue degradation or growth

disturbance. In addition, there is temporal variation in the inflammatory activity which also may

cause a fluctuation in symptoms and signs in the chronic condition (9).

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

For diagnosis of TMJ arthritis, clear and ideally specific clinical criteria should be defined. In

rheumatology, a swollen or painful joint leads to a diagnosis of definite synovitis in that

Accepted Article

particular joint. The TMJ differs to some extent from other synovial joints since the TMJ is

seldom swollen, seldom shows redness and the mechanical pain sensitivity over the TMJ is only

weakly, if at all, related to an inflammatory intraarticular milieu but rather to systemic

inflammatory factors (10). The recently published Expanded taxonomy for diagnostic criteria

for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) (9) lists Arthritis under the classification

Temporomandibular joint disorders - Joint pain and states the following criteria: TMJ pain and

swelling, redness and/or increased temperature in front of the ear or dental occlusal changes

resulting from articular inflammatory exudate (e.g., posterior open bite). However, TMJ swelling,

redness or increased temperature occurs very rarely (11), which severely limits the possibilities

to identify TMJ arthritis based on cardinal signs. In fact, ongoing chronic TMJ inflammation, i.e.

arthritis, may not show any of the cardinal signs although there is ongoing disease progression.

Earlier diagnostic studies on TMJ arthritis have been hampered by the lack of an established,

valid and reliable reference standard. Today, true synovial fluid concentrations of inflammatory

mediators can be determined from TMJ synovial fluid samples obtained with a joint washing

technique (7), and cut-off values for healthy and inflamed joints are available (7, 10).

The aim of this study was to establish clinical criteria for the diagnosis of TMJ arthritis. By

identifying valid clinical markers for arthritis per se together with determinants for the degree

of inflammatory activity it may be possible to establish a diagnostic grading system where the

presence of TMJ arthritis can be considered. To achieve this, the objectives of the study were i)

to identify the clinical variables with the highest sensitivity and specificity to diagnose TMJ

arthritis using synovial fluid levels of inflammatory mediators as reference standard and ii) to

establish variables that are clinically useful to determine the degree of inflammatory activity in

the arthritic TMJ.

Materials and Methods

Patients and healthy individuals

A total of 219 TMJs from 141 patients and 15 healthy individuals were included in this study

(Table 1). The samples were included from a large (approximately 1050 TMJ synovial fluid

samples) set of samples obtained between 1995 and 2009 at Karolinska Institutet, Department

of Dental Medicine, Section for Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function in Huddinge, Sweden.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Inclusion criteria for the patients/TMJs were i) ongoing TMJ pain or impaired TMJ function or

recent development of anterior open bite (see below for definition) or event/disorder that may

Accepted Article

initiate or maintain TMJ arthritis; ii) TMJ synovial fluid sample that fulfilled the sample quality

criteria (see below) from one or both TMJs (if several eligible samples existed, the latest

samples were included) and iii) verbal consent. Exclusion criteria were age ≤18 years, current

malignancies, TMJ surgery or trauma within 2 years before inclusion or recent intraarticular

corticosteroid injection in the TMJ (within 3 months). Patients whose symptoms could be

mainly related to disease in other components of the trigeminal system (e.g. toothache, myalgia,

neuralgia) were also excluded.

For patients with rheumatic disorders, diagnoses were determined by a medical doctor with

specialty in rheumatology at the Clinic of rheumatology, Karolinska University Hospital,

Huddinge, Sweden. Diagnoses were determined using the American College of Rheumatology

(ACR) or European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria (12-15).

Fifteen healthy adults (>18 years of age): six females and nine males, with a median (25th/75th

percentile) age of 36 (31/44) years and recruited from staff and postgraduate students at the

Department of Dental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet voluntarily agreed to participate. Inclusion

criteria were a statement from the subjects that they did not have any chronic pain or

inflammatory condition and that they considered their orofacial area to be healthy. Exclusion

criteria were symptoms and signs of a chronic pain condition, TMJ dysfunction (TMJ resting

pain, TMJ pain on jaw movement, painful TMJ clickings) and pharmacological treatments that

may interfere with pain or inflammation. Subjects with non-painful joint clicking were allowed.

Table 1 shows age and gender distributions, diagnoses and medications.

This project was approved by the regional ethical committee at Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm, Sweden (176/91; 310/97; 142/02; 03-2004).

This study followed the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD)

guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies (16).

Assessment of subjective symptoms and clinical signs

Each subject was clinically examined by one of two operators (PA, SK) immediately before the

blood and TMJ synovial fluid sampling. The operators were calibrated to each other and the

examination was performed according to the clinical examination routine used in several

previous studies (7, 17-25) . The examination performed in the present study comprised the

following variables.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

- The patients were asked about pain in nine joint regions besides the TMJ (neck,

shoulders, elbows, hands, upper back, lower back, hips, knees and feet) and the number

Accepted Article

of painful joint regions was recorded (score = 0–9).

- A 10-cm visual analogue scale (ACO, Stockholm, Sweden; score 0–10) or a numerical

rating scale 0–10 with end-points marked with No pain and Worst pain ever experienced

were used to assess the current degree of global pain intensity as well as TMJ pain

intensity at rest, on maximum mouth opening and on chewing.

- A score (0–4) for pain to digital palpation of the TMJ was adopted that involved

evaluation of the lateral (palpation over the lateral TMJ pole with the jaw in a resting

position) and posterior (lateral palpation posteriorly of the caput on mouth opening)

aspect of the joint on each side. For each site, one unit was scored if the patient reported

pain upon palpation and two units if the palpation pain also caused a palpebral reflex,

adding up to a maximum score of 4 for each TMJ.

- TMJ crepitus was assessed by digital palpation on maximum mouth opening (at least

three times) and recorded as “absent” or “present”. This corresponds to the definition in

DC/TMD for crepitus even though our examinations were performed long before

DC/TMD was published.

- TMJ pain on mandibular movements (maximum voluntary mouth opening, ipsilateral

and contralateral laterotrusions and protrusion) was recorded separately for each TMJ

as present or absent. One unit was scored for each movement causing TMJ pain on each

side (score 0–4).

- The degree of anterior open bite was used as a coarse clinical marker of the degree of

cartilage and bone destruction in the TMJ and it was assessed by recording of the

occlusal contacts on each side upon hard biting in intercuspid position (2 x 8 μm,

Occlusions-Prüf-Folie, GHM Hanel Medizinal, Nürtingen, Germany). The following scores

were used on each side: 0 = occlusal contacts including the canine, 1 = no contacts

anterior to the first premolar, 2 = no contacts anterior to the second premolar, 3 = no

contacts anterior to the first molar, 4 = no contacts anterior to the second molar and 5 =

no occlusal contact; scoring system adapted from (11). The sum of the scores on the

right and left side was used in the analysis as an estimation of the degree of anterior

open bite. None of the patients in our study was edentulous and the score thus ranged

from 0 to 9. Presence of anterior open bite was defined as a score of ≥5.

Temporomandibular joint synovial fluid sampling

Immediately after the clinical examination, two experienced and specially trained operators

(PA, SK) obtained all TMJ synovial fluid samples. A disposable needle (diameter 0.60 mm) was

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

placed in the superior TMJ compartment after disinfecting the skin with 70% ethanol and 5%

chlorhexidine and auriculotemporalis nerve block with 2.0 mL Lidocaine (Xylocain® 20 mg/mL,

Accepted Article

AstraZeneca, London, United Kingdom). TMJ synovial fluid samples were obtained with a push-

pull technique and the amount of recovered synovial fluid in each sample was quantified with

the hydroxycobalamin method that has a detection limit of <1% synovial fluid in the aspirate, as

described by Alstergren et al. (7, 26, 27). The technique enables determination of the true

synovial fluid concentration of the investigated mediators in the aspirate after saline washing of

the joint. Briefly, a washing solution consisting of 22% hydroxycobalamin (Behepan® 1 mg/mL;

Kabi Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in physiological saline (sodium chloride 9 mg/mL) was used

as washing solution. Each TMJ was washed with a total of 4 mL washing solution through a

valve connecting the syringes for the washing solution and the aspirate. One mL of washing

solution was injected slowly and as much as possible was then aspirated back. The

injection/aspiration was repeated a total of four times for each joint. In order to secure an

intraarticular needle placement, a small aspiration was initially conducted. If aspiration of the

washing solution was possible and the resistance in the syringe was minor during injection then

the placement of the needle tip was considered within the joint space (7, 26, 27).

The aspirates were evaluated for blood contamination (no, minor, clear, or excessive) and

centrifuged at 1500 g at 4° C for 10 minutes (7). The supernatants were then aliquoted into

tubes (specific for each mediator to be analyzed) and frozen at -80° C.

Blood sampling

Venous blood was collected and used for determination of rheumatoid factor level, erythrocyte

sedimentation rate, serum level of C-reactive protein as well as plasma or serum levels of

inflammatory mediators. Rheumatoid factor titers below 15 IE/mL and C-reactive protein levels

below 10 mg/L were considered as zero values according to the standard procedures of the

accredited laboratory at the Department of Clinical Chemistry at Karolinska University Hospital,

Huddinge, Sweden.

Analysis of mediators

The TMJ synovial fluid and blood plasma concentrations of TNF, TNF soluble receptor II

(TNFsRII), IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), IL-1 soluble receptor II (IL-1sRII), IL-6 and

serotonin were determined using commercially available enzyme-linked immunoassays in

which highly specific antibodies were used to detect the mediators (TNF, TNFsRII, IL-1β, IL-1ra,

IL-1sRII, IL-6 ELISAs, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN USA; Serotonin: Serotonin EIA-kit,

Immunotech A Coulter Company, Marseille, France). The assay of synovial fluid concentration of

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

serotonin was modified to be applicable at concentrations between 1.6 and 5000 nmol/L. To

compensate for hydroxocobalamin interaction with the assay, the synovial fluid aspirates were

Accepted Article

read against a standard curve with hydroxocobalamin included (7, 26). The small

hydroxocobalamin interaction was completely compensated for by this procedure.

The median (75th/90th percentile) plasma level of TNF in healthy individuals is 6 (12/18) pg/mL

whereas plasma concentration of IL-1βis undetectable (n = 31), with our assay. Normal

serotonin levels to be expected in human serum according to the manufacturer is 300±700

nmol/L for males and 500±900nmol/L for females.

Reference standard

TMJs with detectable concentrations of either TNF, IL-1βor serotonin or with a TMJ synovial

fluid concentration exceeding the 95th percentile of that from healthy individuals regarding TNF

soluble receptor II (TNFsRII), IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), IL-1 soluble receptor II (IL-

1sRII) or IL-6 were considered as the reference standard for arthritic joints with ongoing

inflammatory activity (Table 2) (7, 17). This was based on data from TMJ synovial fluid from

healthy individuals, where TNF, IL-1βand serotonin were undetectable using the identical

sampling procedure and identical assays. These mediators have been shown to be related to

TMJ arthritis, TMJ pain as well as TMJ cartilage and bone tissue destruction (7, 17, 20-22, 24,

25).

In order to assess the degree of inflammatory activity, all included 219 TMJs were divided into

“No arthritis” and “Arthritis”, according to the definition above. After that, the arthritic TMJs

were further divided into “Low inflammatory activity” and “High inflammatory activity”. High

inflammatory activity was here defined as a TMJ synovial concentration of serotonin exceeding

37 nmol/L or a detectable TNF concentration.

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, median values and 25th/75th percentiles are presented. Data from

patients and healthy individuals were compared with Mann-Whitney U-test. Sensitivity and

specificity for single clinical variables and combinations of clinical variables (pain- and function-

related variables) were calculated, as were the positive and negative likelihood ratios. Logistic

regression was used to calculate the influence of combinations of clinical variables on the

predictive value for presence of arthritis and presented as ROC curves, starting with

combination of all included variables. Acceptable validity for the multivariate tests was defined

as an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of ≥0.70 (28). After each calculation, the variable with the

lowest contribution to the total result was omitted as long as the area under the ROC curve

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

remained >0.70. According to this principle, the cut-off values for each clinical variable were

determined and the sensitivity and specificity were calculated accordingly.

Accepted Article

A separate calculation as described above was performed for joints without pain in order to

calculate factors explaining presence of arthritis in non-painful joints.

In order to investigate the usefulness of the clinical variables for the assessment of

inflammatory activity, the TMJs were grouped into joints with high (median or higher) or low

synovial fluid concentrations of the investigated mediators. The significance of the difference in

findings between joints with high or low inflammatory activity was calculated with Mann-

Whitney U-test. Also, the significance of the correlations between TMJ synovial fluid levels of the

mediators and the TMJ pain variables were analyzed using Spearman’s ranked correlation.

In general, a probability level of P<0.05 was considered as significant. To compensate for

multiple testing regarding differences between patients and healthy individuals as well as

differences between joints with and without arthritis, a probability level of P<0.01 was

considered as significant for those comparisons.

Results

Signs and symptoms from the temporomandibular joint

Table 3 shows all investigated clinical and laboratory variables and the probability level of the

differences between the patients and healthy individuals.

No healthy individual reported any global or TMJ pain. Patients had more global and TMJ pain

and reduced mouth opening capacity compared to healthy individuals but the groups did not

differ in degree of anterior open bite.

Reference standard

Table 3 shows the TMJ synovial fluid concentrations of TNF, TNFsRII, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-1sRII, IL-6

and serotonin in the patients and healthy individuals. In the patients, 71% of the TMJs

compared to 4% (one joint) in the healthy individuals were considered as arthritic according to

the reference standard definition used in this study. There were no significant differences

between men and women regarding TMJ synovial concentrations of TNF, TNFsRII, IL-1β, IL-1ra,

IL-1sRII, IL-6 or serotonin. Age and TMJ synovial fluid concentrations of TNF, TNFsRII, IL-1β, IL-

1ra, IL-1sRII, IL-6 or serotonin were not significantly related.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

In the total material, 13 (7%) out of the 139 joints that fulfilled the reference standard criteria

for arthritis were pain-free. On the other hand, 53 (66%) of the 80 TMJs that did not fulfill the

Accepted Article

criteria for arthritis showed some degree of pain (resting, movement or palpation; Fig. 1).

Univariate analysis

Global pain intensity, TMJ resting pain and TMJ pain on maximum opening and number of jaw

movements causing TMJ pain were significantly higher in TMJs with arthritic than in non-

arthritic joints (Table 4). Laterotrusion to the contralateral side was lower in patients with TMJs

with arthritis than in patients with non-arthritic TMJ arthritis (Table 4).

Crepitus was more prevalent and the laterotrusion to the contralateral side were significantly

smaller in TMJs with non-painful arthritic than in non-arthritic joints (p = 0.005 and p < 0.001,

respectively).

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression using presence of arthritis as the dependent variable and the clinical

variables TMJ resting pain intensity, TMJ maximum opening pain intensity, Number of jaw

movements causing TMJ pain and Laterotrusive movement to the contralateral side as

independent variables statistically explained the presence of arthritis with an area under the

ROC curve = 0.72 (n = 190; p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Logistic regression using presence of arthritis as the dependent variable among joints with no

pain and the independent clinical variables Crepitus and Contralateral laterotrusion found that

these variables statistically explained the presence of arthritis with an area under the ROC curve

= 0.91 (n = 40; p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity

Table 5 shows the sensitivity and specificity of single clinical variables and combinations of

variables to identify arthritis in relation to the reference standard.

The highest sensitivity for a single variable was found for TMJ pain on mandibular movement:

0.71. Corresponding specificity was 0.48. The highest specificity for a single variable was found

for Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm: 0.83 (sensitivity 0.37).

The highest overall sensitivity, 0.89, was found for observing one or more of the following: TMJ

resting pain or TMJ pain on mandibular movements or TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening or

Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm. The corresponding specificity (i.e., observing none of the

variables in a non-arthritic joint) was 0.39. The highest overall specificity was found for the

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

combination TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening and Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm: 0.89.

The sensitivity of this combination was 0.24

Accepted Article

In the non-painful joints, crepitus, short duration of TMJ symptoms and low contralateral

laterotrusion explained TMJ non-painful arthritis to a great extent. The sensitivity of Crepitus (as

single variable) was 0.60 and the specificity was 0.93. The sensitivity of Contralateral

laterotrusion < 8 mm was 0.64 and the specificity was 0.13.

Predictive values

Table 5 shows the predictive values of single clinical variables and combinations of variables to

identify arthritis in relation to the reference standard. Using combinations of variables, the

highest positive predictive value (0.79) was found for the combination of TMJ pain on maximum

mouth opening and Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm (Table 5). The highest negative predictive

value (0.67) was found for TMJ resting pain or TMJ pain on mandibular movements or TMJ pain

on maximum mouth opening or Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm. However, the negative

predictive value for TMJ resting pain alone was 0.66.

The highest positive likelihood ratio (2.20) was found for the combination of the variables TMJ

resting pain, TMJ pain on mandibular movements, TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening and

Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm. At the same time, the lowest negative likelihood ratio (0.28)

was found for not fulfilling any of the criteria TMJ resting pain, TMJ pain on mandibular

movements, TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening or Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm.

Inflammatory activity

Among the arthritic TMJs, TMJs with high inflammatory activity showed significantly higher TMJ

pain on maximum mouth opening (p < 0.001) and higher number of mandibular movements

causing TMJ pain (p = 0.004) than TMJs with low inflammatory activity. Patients with high TMJ

inflammatory activity had higher plasma levels of IL-1β(p = 0.013) than patients with low TMJ

inflammatory activity.

There were not sufficient amounts of data in the non-painful TMJ arthritis group to statistically

calculate a potential relation to inflammatory activity.

Diagnostic procedure

Table 6 and Figure 4 shows the diagnostic criteria for possible, probable and definite TMJ

arthritis.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Discussion

Accepted Article This study suggests diagnostic criteria for TMJ arthritis, as a base for future research into

clinical diagnostics of TMJ arthritis. Already today, there may very well be real clinical value in

these criteria, but at the same time the limitations of the presented data should be considered.

This study also identifies clinical variables indicating high TMJ inflammatory activity among

arthritic TMJs.

Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity

Taken together, the joint-related variables TMJ resting and maximum opening pain intensity,

number of jaw movements causing TMJ pain and laterotrusive movement to the contralateral side

showed an acceptable diagnostic performance when combined. In the post-hoc analysis, where

sensitivity and specificity are inversely related, we adopted the use of “Possible”, “Probable” and

“Definite TMJ arthritis” levels in order to create a model for levels of diagnostic certainty and

accuracy.

The inclusion criteria of this study comprised “Ongoing TMJ pain, impaired TMJ function or

recent development of anterior open bite or event/disorder that may initiate or maintain TMJ

arthritis”. There was thus a selection of patients by anamnestic data before the clinical data

were applied to determine the diagnosis “TMJ arthritis”. Accordingly, in our suggested criteria,

we recommend that these anamnestic data are assessed prior to applying the criteria in order to

filter out cases highly unlikely to be afflicted with TMJ arthritis. The prevalence of patients with

arthritic TMJs that have anamnestic data of ongoing TMJ pain, impaired TMJ function or recent

development of anterior open bite or event/disorder that may initiate or maintain TMJ arthritis

should therefore not differ much between patients identified by these anamnestic criteria in the

general population, in general dentistry and in a specialist clinical with referred patients. The

positive and negative predictive values are dependent on the prevalence of the investigated

condition in the sample. We therefore calculated PPV and NPV for the true prevalence in the

sample (71%) as well as for a prevalence of 50% representing a chance distribution.

The lowest level of diagnostic certainty, “Possible TMJ arthritis” was best indicated by TMJ pain

on maximum opening. This clinical criterion gave a sensitivity of 0.63 and a specificity of 0.56.

Although these values are not impressively high, on the group level this single criterion will

correctly identify a majority of the joints with arthritis as well as exclude arthritis in the

majority of healthy joints. Considering the suboptimal accuracy, as an only criterion TMJ pain on

maximum opening is not sufficient to diagnose TMJ arthritis with a high enough level of

certainty. The clinical description “Possible TMJ arthritis” may therefore best be considered as a

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

preliminary assessment of the TMJ, indicating the need of a more thorough examination and

perhaps referral to a specialist.

Accepted Article

The higher diagnostic level of “Probable TMJ arthritis” combined TMJ pain on maximum mouth

opening with a Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm. Our results indicate that if both these criteria

are fulfilled, the likelihood of a true TMJ arthritis is considerably higher than at the level of

“Possible TMJ arthritis”. Perhaps even more importantly: if the two criteria are not fulfilled,

arthritis can be excluded in 89% of the healthy TMJs.

“Definite TMJ arthritis”, as suggested in the present study, involves TMJ synovial fluid sampling

and laboratory analyses of inflammatory mediators in those samples. Although not particularly

difficult to perform in itself, this procedure requires equipment, procedures, experience and

knowledge. It is also probably important that the operator perform this procedure a number of

times per year in order to develop and retain the knowledge and skills required. That said, a

diagnosis of “Definite TMJ arthritis” may be of great clinical value in cases where there is a

“silent” arthritis, i.e. an TMJ arthritis without pain but with structural damage or growth

disturbance that is not possible to detect by clinical examination. TMJ synovial fluid sampling

may therefore have a great potential as a diagnostic tool and should be considered in selected

cases.

The sensitivity for the variable TMJ pain at rest was unexpectedly high, especially as movement

and loading pain is believed to be the most prominent pain aspects of arthritis. However, TMJ

pain at rest is most likely an unspecific clinical variable since it may include pain not related to

the joint proper more than movement pain, which can explain the high sensitivity but on the

other hand it has a low specificity. Certainly, arthritis may cause resting pain by activating

sensitized nociceptive fibers in and around the joint or by central mechanisms. The findings in

the present study suggest that also minor pain intensity is of importance since the sensitivity

increased when also minor pain intensity was included.

About 17% of the TMJs that were classified as arthritic did not present any clinical pain findings.

Chronic arthritis may very well be present without pain, although pain is common (6, 8-11). On

the other hand, 78% of the TMJs without arthritis showed pain at rest or on provocation by

movement or palpation. This pain is most probably due to sensitization, peripheral or central or

a combination, of the articular or adjacent tissues of a non-inflammatory nature. It may also be

due to pain related to internal derangements, without an apparent inflammatory component.

This is one likely explanation to why pain on palpation and, especially pressure-pain thresholds,

over the TMJ, has been primarily related to systemic factors and not to local inflammatory

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

factors (10). The frequent finding of pain despite absence of local inflammation of the joint

suggests that clinical criteria of TMJ arthritis should not be limited to pain variables, but should

Accepted Article

also assess function. In the present study, the degree of anterior open bite and range of

movements were included as primarily non-pain-related variables in an attempt to investigate

the diagnostic value of these functional variables. Indeed, impaired range of movements is

usually related to joint pain but there may also be other mechanical factors behind restricted

movement in arthritis, for example fibrous adhesions or internal derangements (17). Anterior

open bite, especially progressive anterior open bite, is a clinical sign of ongoing or severe/rapid

TMJ cartilage and bone tissue destruction and not uncommon among patients with more severe

forms of arthritis, e.g. RA (7, 11, 24, 25). Anterior open bite is usually a late sign but it may still

be the first sign of TMJ arthritis if pain is absent. In the present study, anterior open bite was

used as a crude marker for TMJ cartilage and bone tissue destruction. It has obvious limitations

and anterior open bite may certainly be caused by other conditions than arthritis.

Unfortunately, an anterior open bite due to bilateral TMJ cartilage and bone tissue destruction is

a severe complication and may be very difficult to treat. This supports the use of TMJ synovial

fluid sampling and subsequent analyses of inflammatory mediators for “Definite TMJ arthritis”

diagnosis in some cases, such as when occlusal changes appear suddenly or are progressing

rapidly, especially in the absence of pain.

The clinical examination in this study was not performed exactly according to the DC/TMD

protocol. DC/TMD was published in 2014 and our examinations were performed between 1995

and 2009. The examination procedure used in the present study was identical to most other

studies on TMJ arthritis during that time. Interestingly, most of our investigated variables were

assessed in a similar manner to the clinical examination in DC/TMD. For example, maximum

mouth opening capacity without assistance, presence of TMJ pain on mouth opening,

laterotrusion and protrusion and assessment of crepitus are almost identical. In the future, our

findings should therefore be possible to use as a base in research into diagnostics of TMJ

arthritis using the DC/TMD.

So far, no clinical diagnostic criteria for TMJ arthritis have been established. In part, this may be

due to a lack of an adequate reference standard. In the present study, we used a reference

standard based on TMJ synovial fluid concentrations of a number of inflammatory mediators,

for which there were either known and published distinct differences between non-arthritic and

arthritic joints, or TMJ synovial fluid concentrations exceeding the 95th percentiles for healthy

TMJs (7, 10). Also, validated sample quality criteria were used to ensure that only high-quality

TMJ synovial fluid samples were included in the study. To our knowledge, this is the first time a

laboratory test based reference standard has been applied, for the TMJ or any other joint. Our

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

reference standard was based on determination of the true synovial fluid concentration of

certain mediators using washing of the joint with the vitamin B12-method developed and

Accepted Article

published by us (7, 26, 27). Although this reference standard may have its limitations in

assessing arthritis, we consider it to at least as accurate as any other available reference

standard including magnetic resonance imaging (9). Another previously adopted reference

standard is expert opinion, based partly on clinical findings, which is problematic in a scientific

context because of the circularity in argument and risk of overestimation of accuracy (29). A

biomarker test, such as synovial fluid sampling with standardized laboratory analysis, has the

advantage of being independent of the clinical findings, an important methodological

requirement in studies of diagnostic accuracy (30).

In the non-painful joints, crepitus and impaired contralateral laterotrusion explained non-

painful TMJ arthritis to a great extent. This condition, which is fairly common according to this

study and difficult to identify clinically, warrants more attention.

Inflammatory activity

Characteristic for TMJs with high inflammatory activity was TMJ pain on mandibular

movements. If a TMJ fulfills the clinical diagnostic criteria for arthritis suggested above,

presence of TMJ pain on mandibular movements may thus indicate a higher inflammatory

activity. TMJ pain on jaw movements has been found to be strongly related to an inflammatory

intraarticular milieu in other studies (10, 18-20). TMJ pain on jaw movement thus seems to be

of relevance as a clinical sign of TMJ arthritis. It may be of importance for a clinical diagnosis

and subsequently for choice of therapy and for monitoring therapy effectivity. However, there is

a need for studies that focus on this aspect before we will know if assessment of inflammatory

activity is possible, relevant and clinically useful.

Methodological considerations

This study proposes a diagnostic model for TMJ arthritis by the use of certainty levels possible,

probable and definite TMJ arthritis. The model is based on clinical findings (pain-related

variables and functional variables). Single variables and combinations of variables were

compared to the presence of the inflammatory mediators in the TMJ synovial fluid. These

mediators have previously been shown to be related to both TMJ pain and tissue destruction in

patents with systemic inflammatory joint diseases (20-25, 27).

In the present study, the prevalence of TMJ arthritis among the included patients can be

expected to be higher than in the population since the patients were referred to a specialist

clinic due to orofacial pain and jaw dysfunction, and many patients were in fact referred from

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

rheumatologists. The reference standard tells us that 65% of the TMJs in the sample were

arthritic according to presence of inflammatory mediators in the synovial fluid. The prevalence

Accepted Article

in the general population according to our proposed criteria is unknown, using the criteria in

this study, but can be expected to be less than 65%. This means that the positive predictive

values in the population is likely lower.

Considering the complex nature of chronic TMJ arthritis, which may or may not include pain,

functional limitations, cartilage and bone tissue destruction and growth inhibition (in

adolescents), the variables included in this study cannot fully encompass all the above aspects of

chronic TMJ arthritis. In the present study, only degree of anterior open bite was included as an

estimation of TMJ cartilage and bone tissue destruction. It is probably a coarse and late sign of

TMJ bone tissue destruction. There may, in addition, be anamnestic information of importance

for diagnosis, for example recent occlusal changes, TMJ pain on chewing, TMJ pain with

aftersensation etc. These were not investigated in this study. Chronic TMJ arthritis may not

always include pain. In those cases, the inflammation may very likely be a silent type of

inflammation, causing cartilage and bone tissue destruction or, in adolescents, growth

disturbances as well but with no or very low intensity pain. In the present study, almost one-

fifth of the TMJs with arthritis were pain-free, indicating that pain-free arthritis is not

uncommon. In addition, diagnosis of early arthritis is important to improve treatment

prognosis. In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published new diagnostic

criteria for RA where early diagnosis was in focus (31). However, early diagnosis could not be

considered in the present study. Our findings must, therefore, be considered as a major first

step towards accurate and comprehensive diagnostic criteria that need to be tested in future

studies.

The included patients had systemic inflammatory diseases (RA, PsA, ankylosing spondylitis etc)

or local TMJ arthritis. The purpose was to include the whole spectrum of systemic and local TMJ

conditions. No patients had been treated with intraarticular corticoids for at least three months

before sampling. Because the inflammatory process is unspecific, the factors involved in the

inflammation are likely to be similar and unlikely to vary a lot depending on the type of

underlying disorder. However, for some of the rheumatic disorders the presence of

autoantibodies like anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) is

common and strongly contribute to immune system activation and thereby increased

inflammatory activity.

The control group of healthy individuals may seem small when considering the number of

subjects However, sampling from healthy TMJs may not be allowed nowadays from an ethical

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

point-of-view, so this control group can be considered as unique compared to other studies, and

contributes with valuable data. To clarify, all samples from healthy individuals and patients

Accepted Article

were obtained with ethical approval.

In our material, one could argue that there were actually three groups: i) healthy (no arthritis),

ii) patients with TMJ arthritis and iii) patients with conditions that may cause TMJ arthritis but

where the synovial fluid sample could not confirm active arthritis (i.e. a patient control group

without TMJ arthritis). The inclusion of patients without active TMJ arthritis for comparison

with the patients with active TMJ arthritis is very important, and especially relevant since the

clinical presentation of chronic inflammation at a given time point may be anywhere on a

continuum from no sign or symptom whatsoever to any combination of pain, swelling/exudate,

tissue degradation or growth disturbance. Just like patients with active TMJ arthritis represent

one extreme of the continuum, the healthy individuals represent the other extreme, and

therefore contribute to understanding of the whole spectrum. Because of the relatively small

group size, our conclusions regarding findings in healthy individuals remain very conservative.

Conclusion

This study proposed clinical diagnostic criteria for TMJ arthritis, as a base for future research

into clinical diagnostics of TMJ arthritis. The clinical variables TMJ pain on maximum mouth

opening and Contralateral laterotrusion of less than 8 mm appear to have high clinical diagnostic

value. Already today, there may very well be clinical value in these criteria but at the same time

the limitations in knowledge should be considered.

The study also identified clinical variables indicating high TMJ inflammatory activity among

arthritic TMJs.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the laboratory technicians Karin Trollsås, Agneta Gustafsson and Kari

Eriksson for their tremendous work, as well as the healthy individuals that participated.

This research was funded by the Swedish Council of Medical Research, the National Institute of

Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR; R01-DE15420), the Schering-Plough Corporation, and

the Swedish Dental Society.

Dr. Alstergren reports grants from Svenska Tandläkare-Sällskapet, grants from Schering-Plough,

grants from NICDR, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Kopp reports grants from Svenska

Tandläkare-Sällskapet, grants from Schering-Plough, grants from NICDR, during the conduct of

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

the study. The other author has stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in

connection with this article.

Accepted Article

References

1. Dias IM, Coelho PR, Picorelli Assis NM, Pereira Leite FP, Devito KL. Evaluation of the

correlation between disc displacements and degenerative bone changes of the

temporomandibular joint by means of magnetic resonance images Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2012; 41: 1051-1057.

2. Dias IM, Cordeiro PC, Devito KL, Tavares ML, Leite IC, Tesch Rde S. Evaluation of

temporomandibular joint disc displacement as a risk factor for osteoarthrosis Int J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 2016; 45: 313-317.

3. Stabrun AE, Larheim TA, Hoyeraal HM. Temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile

rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical diagnostic criteria Scand J Rheumatol. 1989; 18: 197-204.

4. Olson L, Eckerdal O, Hallonsten AL, Helkimo M, Koch G, Gare BA. Craniomandibular function

in juvenile chronic arthritis. A clinical and radiographic study Swed Dent J. 1991; 15: 71-83.

5. Kjellberg H, Fasth A, Kiliaridis S, Wenneberg B, Thilander B. Craniofacial structure in children

with juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA) compared with healthy children with ideal or postnormal

occlusion Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995; 107: 67-78.

6. Bakke M, Zak M, Jensen BL, Pedersen FK, Kreiborg S. Orofacial pain, jaw function, and

temporomandibular disorders in women with a history of juvenile chronic arthritis or

persistent juvenile chronic arthritis Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001; 92:

406-414.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

7. Alstergren P, Kopp S, Theodorsson E. Synovial fluid sampling from the temporomandibular

Accepted Article joint: sample quality criteria and levels of interleukin-1 beta and serotonin Acta Odontol Scand.

1999; 57: 16-22.

8. Doria A, Putterman C, Sarzi-Puttini P, Szekanecz Z, Shoenfeld Y. Controversies in rheumatism

and autoimmunity Autoimmun Rev. 2012; 11: 555-557.

9. Peck CC, Goulet JP, Lobbezoo F, Schiffman EL, Alstergren P, Anderson GC et al. Expanding the

taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders J Oral Rehabil. 2014; 41:

2-23.

10. Alstergren P, Fredriksson L, Kopp S. Temporomandibular joint pressure pain threshold is

systemically modulated in rheumatoid arthritis J Orofac Pain. 2008; 22: 231-238.

11. Tegelberg A, Kopp S. Clinical findings in the stomatognathic system for individuals with

rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthrosis Acta Odontol Scand. 1987; 45: 65-75.

12. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS et al. The American

Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis

Arthritis Rheum. 1988; 31: 315-324.

13. Tillett W, Costa L, Jadon D, Wallis D, Cavill C, McHugh J et al. The ClASsification for Psoriatic

ARthritis (CASPAR) criteria--a retrospective feasibility, sensitivity, and specificity study J

Rheumatol. 2012; 39: 154-156.

14. Raychaudhuri SP, Deodhar A. The classification and diagnostic criteria of ankylosing

spondylitis J Autoimmun. 2014; 48-49: 128-133.

15. Anonymous American College of Rheumatology [Web Page]. [ 2017 11/05]. Available from:

http://www.rheumatology.org.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

16. Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Hooft L, Moher D et al. STARD for

Accepted Article Abstracts: essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies in journal or conference

abstracts BMJ. 2017; 358: j3751.

17. Alstergren P, Ernberg M, Kvarnstrom M, Kopp S. Interleukin-1beta in synovial fluid from the

arthritic temporomandibular joint and its relation to pain, mobility, and anterior open bite J

Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998; 56: 1059-65; discussion 1066.

18. Alstergren P, Kopp S. Pain and synovial fluid concentration of serotonin in arthritic

temporomandibular joints Pain. 1997; 72: 137-143.

19. Alstergren P, Ernberg M, Kopp S, Lundeberg T, Theodorsson E. TMJ pain in relation to

circulating neuropeptide Y, serotonin, and interleukin-1 beta in rheumatoid arthritis J Orofac

Pain. 1999; 13: 49-55.

20. Nordahl S, Alstergren P, Kopp S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in synovial fluid and plasma

from patients with chronic connective tissue disease and its relation to temporomandibular

joint pain J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000; 58: 525-530.

21. Nordahl S, Alstergren P, Eliasson S, Kopp S. Radiographic signs of bone destruction in the

arthritic temporomandibular joint with special reference to markers of disease activity. A

longitudinal study Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001; 40: 691-694.

22. Voog U, Alstergren P, Eliasson S, Leibur E, Kallikorm R, Kopp S. Inflammatory mediators and

radiographic changes in temporomandibular joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis Acta

Odontol Scand. 2003; 61: 57-64.

23. Alstergren P, Benavente C, Kopp S. Interleukin-1beta, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and

interleukin-1 soluble receptor II in temporomandibular joint synovial fluid from patients with

chronic polyarthritides J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61: 1171-1178.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

24. Voog U, Alstergren P, Eliasson S, Leibur E, Kallikorm R, Kopp S. Progression of radiographic

Accepted Article changes in the temporomandibular joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in relation to

inflammatory markers and mediators in the blood Acta Odontol Scand. 2004; 62: 7-13.

25. Alstergren P, Kopp S. Insufficient endogenous control of tumor necrosis factor-alpha

contributes to temporomandibular joint pain and tissue destruction in rheumatoid arthritis J

Rheumatol. 2006; 33: 1734-1739.

26. Alstergren P, Appelgren A, Appelgren B, Kopp S, Lundeberg T, Theodorsson E.

Determination of temporomandibular joint fluid concentrations using vitamin B12 as an

internal standard Eur J Oral Sci. 1995; 103: 214-218.

27. Alstergren P, Appelgren A, Appelgren B, Kopp S, Nordahl S, Theodorsson E. Measurement of

joint aspirate dilution by a spectrophotometer capillary tube system Scand J Clin Lab Invest.

1996; 56: 415-420.

28. Hajian-Tilaki K. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Medical

Diagnostic Test Evaluation Caspian J Intern Med. 2013; 4: 627-635.

29. Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Naeije M. Some remarks on the RDC/TMD Validation Project:

report of an IADR/Toronto-2008 workshop discussion J Oral Rehabil. 2010; 37: 779-783.

30. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a

tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003; 3: 25.

31. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO,3rd et al. 2010 Rheumatoid

arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against

Rheumatism collaborative initiative Arthritis Rheum. 2010; 62: 2569-2581.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

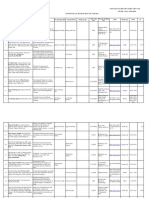

Table 1

Accepted Article Age, distribution of gender and diagnoses, duration of disease and use of medication in 141

patients with various degrees of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis and 15 healthy

individuals.

Percentiles

Median 25th 75th n

PATIENTS

Age years 51 40 60 141

Distribution of gender according to diagnosis Rheumatoid arthritis M/W 10/65

Psoriatic arthritis M/W 7/13

Ankylosing spondylithis M/W 4/8

Other systemic inflammatory diseases M/W 0/20

Monoarthritic conditions M/W 2/12

Duration of systemic disease years 10 4 20 126

Duration of TMJ disease years 4 1 10 127

Medication (analgesic, antiinflammatory or immunomodulating) Paracetamol 19 (13%)

NSAID 46 (33%)

Corticosteroid 23 (16%)

DMARD 34 (24%)

Anti-TNF 0 (0%)

Other biologic 0 (0%)

Total 93 (66%)

HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS

Age years 36 31 44 15

Distribution of gender M/W 9/6

n = number of observations, M = men, W = women, NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs, DMARD = disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 2

Accepted Article Reference standard definition of temporomandibular joint

(TMJ) arthritis

Cut-off for

Mediator

arthritis

Serotonin nmol/L >0

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pg/mL >0

TNF soluble receptor II pg/mL >2624

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) pg/mL >0

IL-1 receptor antagonist pg/mL >1168

IL-1 soluble receptor II pg/mL >2400

IL-6 pg/mL >60

Cut-off values are based on TMJ synovial fluid

concentrations from healthy individuals from our

laboratory. If a mediator is detectable in healthy TMJ

synovial fluid, the 95th percentile value from healthy

individuals was used as cut-off value.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 3

Clinical and laboratory findings in 141 patients/195 temporomandibular joints (TMJ) with various degrees of TMJ arthritis and 15 healthy

Accepted Article individuals/24 TMJs.

PATIENTS HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS

Perccentiles Percentiles

Median 25th

h 75th % pos n Median 25th 75th % pos n P

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Related to the individual

Number of painful regions 0-9 6 4 7 98 117 0 0 0 0 14 <0.001

Global pain intensity NRS 0-10 4 3 6 94 96 0 0 0 0 14 <0.001

Maximum mouth opening mm 38 32 44 n.a. 128 49 48 60 n.a. 15 <0.001

Anterior open bite 0-9 0 0 2 n.a. 141 0 0 1 n.a. 15 0.100

Related to the temporomandibular joint

Pain intensity, rest NRS 0-10 4 2 7 84 167 0 0 0 0 24 <0.001

Pain intensity, mouth opening NRS 0-10 1 0 4 66 195 0 0 0 0 24 <0.001

Pain on mouth opening 0/1 63 195 0 24 <0.001

Pain on ipsilateral laterotrusion 0/1 40 182 0 24 <0.001

Pain on contralateral laterotrusion 0/1 47 182 0 24 <0.001

Pain on protrusion 0/1 49 182 0 24 <0.001

Number of jaw movements causing TMJ pain 0-4 2 0 3 71 195 0 0 0 0 24 <0.001

Pain score on TMJ palpation, lateral 0-2 0 0 2 69 182 0 0 0 17 24 <0.001

Pain score on TMJ palpation, lateral-posterior 0-2 0 0 1 45 104 0 0 0 12 24 0.003

Pain score on TMJ palpation, total 0-4 1 0 2 71 182 0 0 0 29 24 0.003

Laterotrusion to the contralateral side mm 9 7 10 n.a. 182 11 11 12 n.a. 24 <0.001

Crepitus 0-3 0 0 1 30 182 0 0 0 0 24 <0.001

Table 4

Accepted Article Significant differences in univariate analysis between patients/temporomandibular joints (TMJ) with and without arthritis.

ARTHRITIS NOT ARTHRITIS

Percentile Percentile

Variable Median 25th 75th n Median 25th 75th n P

Global pain intensity NRS 0 - 10 5 3 7 76 2 0 4 54 < 0.001

TMJ pain

Resting pain intensity NRS 0 - 10 4 2 7 120 1 0 5 71 0.002

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening NRS 0 - 10 2 1 5 132 0 0 1 76 < 0.001

Number of painful TMJ movements 0-4 2 0 3 139 1 0 2 80 0.009

Laterotrusion, contralateral mm 9 6 10 131 10 8 12 65 < 0.001

n = number of observation; P = probability level of the difference between TMJ arthritis in patients/TMJs for each variable.

NRS = numerical rating scale 0 - 10.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 5

Accepted Article Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for single variables and combinations of variables for

diagnosis of temporomandibular joint arthritis

Diagnostic performance

Variable(s) Sensitivity Specificity PPV NPV

Single variables

TMJ resting pain 0,86 0,46 0,73 0,66

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening 0,63 0,56 0,72 0,47

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening >2/10 0,40 0,78 0,75 0,42

TMJ pain on mandibular movement 0,71 0,48 0,70 0,49

TMJ pain on mandibular movement (>1 movement) 0,60 0,56 0,70 0,45

TMJ pain on mandibular movement (>2 movements) 0,41 0,71 0,71 0,41

Contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm 0,37 0,83 0,79 0,43

Combinations of variables

TMJ resting pain OR 0,83 0,48 0,73 0,61

TMJ pain on mandibular movement

TMJ resting pain AND 0,55 0,61 0,71 0,44

TMJ pain on mandibular movement

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening OR 0,75 0,50 0,72 0,53

contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening AND 0,24 0,89 0,79 0,40

contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm

TMJ resting pain OR 0,89 0,39 0,72 0,67

TMJ pain on mandibular movements OR

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening OR

contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm

TMJ resting pain AND 0,22 0,90 0,79 0,40

TMJ pain on mandibular movements AND

TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening AND

contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm

PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Table 6

Suggested diagnostic levels for TMJ arthritis

Accepted Article

Diagnostic performance

Level Criteria Prevalence Sensitivity Specificity PPV NPV

Possible TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening 71% 0,63 0,56 0,72 0,47

50% 0,63 0,56 0,59 0,60

Probable TMJ pain on maximum mouth opening AND 71% 0,24 0,89 0,79 0,40

contralateral laterotrusion < 8 mm 50% 0,24 0,89 0,69 0,54

Definite Pathological concentration of inflammatory 1,00 1,00

mediators in TMJ synovial fluid

PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value

Figure legends

Figure 1

Distribution of pain symptoms in a total of 219 TMJs with arthritis (n=139) and without

arthritis (n=80) as determined by synovial fluid sampling and analysis of inflammatory

mediators.

Figure 2

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing the diagnostic sensitivity and 1-

specificity regarding temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis for the combinations of the

variables TMJ resting pain, Maximum opening pain intensity, Number of jaw movements causing

TMJ pain and Laterotrusive movement to the contralateral side. This combination significantly

explained presence of TMJ arthritis with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) = 0.72 (n = 190; p <

0.001)

Figure 3

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing the diagnostic sensitivity and 1-

specificity regarding temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis among joints with no pain for the

combinations of the variables Crepitus and Contralateral laterotrusion < 8mm. This combination

significantly explained presence of TMJ arthritis with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) = 0.91

(n = 40; p < 0.001)

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Figure 4

Proposed diagnostic classification for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- UW Step 2 CK Peds-Update 1Document572 pagesUW Step 2 CK Peds-Update 1Selena Gajić100% (3)

- Adult Nasogastric Insertion and Removal ProcedureDocument8 pagesAdult Nasogastric Insertion and Removal ProcedureAna MarieNo ratings yet

- Book Immunotec TestimoniesDocument164 pagesBook Immunotec Testimoniesapi-3714923100% (2)

- Class 4 18 Fetal MonitoringDocument6 pagesClass 4 18 Fetal Monitoringhkkdt2yz6wNo ratings yet

- Rle Focus PDFDocument8 pagesRle Focus PDFCarmina AlmadronesNo ratings yet

- Danh Sach Bai Bao Quoc Te 2020 794Document14 pagesDanh Sach Bai Bao Quoc Te 2020 794Master DrNo ratings yet

- Immunology Laboratory Activity 2Document2 pagesImmunology Laboratory Activity 2James Carbonell Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Letters To The Editor: Anaesthetic Training in Accident and EmergencyDocument1 pageLetters To The Editor: Anaesthetic Training in Accident and EmergencyRamiro Castro ApoloNo ratings yet

- Rüthrich2021 Article COVID-19InCancerPatientsClinicDocument11 pagesRüthrich2021 Article COVID-19InCancerPatientsClinicdianaNo ratings yet

- NCP NHLDocument14 pagesNCP NHLSharlene Myrrh Licudan ManubayNo ratings yet

- Bronchiolitis in Children Diagnosis and Management PDF 51048523717Document21 pagesBronchiolitis in Children Diagnosis and Management PDF 51048523717Pinkymekala HasanparthyNo ratings yet

- Pharma LectureDocument68 pagesPharma LectureMax LocoNo ratings yet

- Repaglinide LDocument19 pagesRepaglinide LbigbullsrjNo ratings yet

- The Last Second MRCP PACES 4th Edition Sample PDFDocument85 pagesThe Last Second MRCP PACES 4th Edition Sample PDFTahir Ali100% (3)

- Practice-Tests Correction: Estimated Grade BDocument1 pagePractice-Tests Correction: Estimated Grade BDr. Emad Elbadawy د عماد البدويNo ratings yet

- Jnma, Apar PokharelDocument6 pagesJnma, Apar PokharelNicca RodilNo ratings yet

- Drug Mechanism of Action/side Effects Indication/ Contraindication Nursing ResponsibilitiesDocument2 pagesDrug Mechanism of Action/side Effects Indication/ Contraindication Nursing ResponsibilitiesSheryhan Tahir BayleNo ratings yet

- IsoxsuprineDocument1 pageIsoxsuprineAndrean EnriquezNo ratings yet

- The SonopartogramDocument20 pagesThe SonopartogramLoisana Meztli Figueroa PreciadoNo ratings yet

- 14 Somatoform DisordersDocument13 pages14 Somatoform DisordersEsraRamosNo ratings yet

- PRIMED2 - A Sex Guide For Trans Men Into MenDocument36 pagesPRIMED2 - A Sex Guide For Trans Men Into MenoblivnowNo ratings yet

- Hypovolemic Shock Concept MapDocument1 pageHypovolemic Shock Concept MapJM AsentistaNo ratings yet

- MetLife Egypt Medical Provider May-2019 English-ArabiconDocument156 pagesMetLife Egypt Medical Provider May-2019 English-Arabiconمحمد صبحيNo ratings yet

- Assia CV EngDocument1 pageAssia CV Engassia ben yahiaNo ratings yet

- Dental Surgeon ResumeDocument4 pagesDental Surgeon Resumeafmsheushbqoac100% (1)

- ASCVD Risk Score - 062719 - KRODocument1 pageASCVD Risk Score - 062719 - KROSKNo ratings yet

- Ketorolac and NalbuphineDocument4 pagesKetorolac and NalbuphineMaureen Campos-PineraNo ratings yet

- The Gynaecologist'S and Obstetrician'S Journal Monthly Continuing Medical Training JournalDocument5 pagesThe Gynaecologist'S and Obstetrician'S Journal Monthly Continuing Medical Training JournalSeulean BogdanNo ratings yet

- Microbiology 3 RD SemesterDocument12 pagesMicrobiology 3 RD SemesterbethelNo ratings yet

- Biostats and Epi-UworldDocument3 pagesBiostats and Epi-UworldMikeRSteinNo ratings yet