Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Economics and Organization PDF

Uploaded by

UzielVPOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Economics and Organization PDF

Uploaded by

UzielVPCopyright:

Available Formats

Economics and

Organization:

A PRIMER

Oliver E. Williamson

oes organization matter to an understanding of the modern corpora-

D tion and to the design of public policy that affects it? The answer to

that question has changed considerably during the past 40 years.

Although if the microeconomics textbooks used in most MBA

courses are to be believed, the answer—both in 1955 and 1995—is that the

organization does not matter very much.

Successive Developments

A unifying theme—but not a unified theory—runs throughout the MBA

curriculum: How does the well-run business firm function? All of the core

courses—marketing, production, organizational behavior, finance, accounting,

economics—address this question. Of these, the discipline of economics is the

most general and arguably speaks with the greatest academic authority.

The basic theory of the firm that is featured in microeconomics textbooks

describes the firm in technological terms as a “production function” in which

inputs (labor, capital) are transformed into outputs (goods, services) according to

the laws of technology. Upon assigning an objective function to the firm (usually

profit maximization) and describing the market in which it operates, students

learn how firms set price and output and respond to changing opportunities

(demand, input prices).

Helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper by Glenn Carroll and Pablo Spiller are gratefully

acknowledged.

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 131

Economics and Organization: A Primer

This is important material and some of the associated ideas—marginal

analysis, opportunity costs, tradeoffs—have truly wide application. Every MBA

who understands these concepts and can apply them to the business environ-

ment has a big advantage. But does this theory, or more generally this approach,

help us to understand the size, shape, and purposes served by the modern cor-

poration and other forms of complex economic organization?

If firms are mainly technological entities, then their natural boundaries

will be determined principally by technological economies of scale and scope.

But firms that extend their boundaries beyond these natural limits then pose

a puzzle. What explains these boundary-extension efforts?

Economists looked in their tool box and pulled out what appeared to be a

general purpose explanation: monopoly was responsible for horizontal, vertical,

and conglomerate structures and, more broadly, for nonstandard and unfamiliar

contracting practices. Public policy toward antitrust was significantly influenced

by this monopoly predilection. What came to be known as the “inhospitality

tradition” took shape. Donald Turner captured the spirit of the 1960s (during his

term as the head of the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice) in

his remark: “I approach customer and territorial restrictions not hospitably in

the common law tradition, but inhospitably in the tradition of antitrust.”1

Albeit widely shared, not everyone was persuaded. The 1991 Nobel Prize

Winner in Economics, Ronald Coase, was among the first to take vigorous

exception with these monopoly predilections. As he expressed it in 1972:

One important result of this preoccupation with the monopoly problem is that if

an economist finds something—a business practice of one sort or another—that

he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation. And as in this field

we are very ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to be

rather large, and the reliance on monopoly explanation, frequent.2

Overcoming this condition of ignorance was the challenge. But how to

accomplish this?

One possibility was to deepen our understanding of technology. Another

possibility was to take the study of organization more seriously. Herbert Simon,

also a Nobel Prize Winner in Economics, urged the latter.3 He argued for a focus

on decision processes and coalition formation, rather than technology, as the

basis for the theory of the firm. The influential book by Richard Cyert and

James March, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm,4 was published soon thereafter.

That book dealt with the process of managerial decision making—with

emphasis on goal formation, search, choice, organizational learning, and the

like—and worked at a very microanalytic level of activity. For example, Cyert

and March developed a computer model of department store pricing that

predicted standard and sale prices to the penny. Albeit an impressive accom-

plishment, it was of much greater interest to department store managers and

marketing specialists than it was to economists and other students of public pol-

icy analysis—most of whom were uninterested in the details of department store

132 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

prices but had an abiding interest in the types of customer, territorial, and other

restrictions.

If anything, economists’ predilections to dismiss organization were “con-

firmed” by the fact that the intersection between the interests of neoclassical

economic theory and the applications of behavioral organization theory

appeared to be so slight. Accordingly, economists who were interested in pre-

dicting price and output and who explained nonstandard and unfamiliar busi-

ness practices in monopoly terms were encouraged to believe that they could

continue to ignore issues of internal organization.

“Transaction cost economics” approaches the study of economic organi-

zation differently. It asks whether economics and organization theory can be

combined in a way that (more veridically) addresses the very same phenomena—

horizontal, vertical, and conglomerate mergers; nonstandard and unfamiliar

contracting practices—that were of interest to students of antitrust and regula-

tion. This perspective describes firms and markets as alternative modes of gov-

ernance. If firms and markets are alternative modes of organization, then the

boundary of the firm needs to be derived rather than taken as given (by tech-

nology). If firms and markets are governance structures for managing transactions,

then organizational rather than technological features come to the fore.

Reformulating the problem of economic organization in this combined

economics and organization way, transaction cost economics advanced a rival

hypothesis to that of the antitrust orthodoxy. It argued that the main purpose

and effect of economic organization was not to create monopoly, but to econo-

mize on transaction costs. Not only did better explanations for many old puzzles

begin to appear, but transaction cost economics called attention to and helped

to explain hitherto neglected questions. For example, what are the different

mechanisms through which firms and markets work that distinguish one from

the other? What purposes are served by economic organization? Which transac-

tions are organized how and why?

What’s Going on Here?

The very considerable accomplishments of economic orthodoxy notwith-

standing, its limits become evident by examining a series of particulars.

Vertical Market Structures

Working out of the firm-as-production function construction in which

technology is largely determinative and nonstandard forms are presumed to

operate in the service of monopoly, orthodoxy held that the vertical integration

(unified ownership) of successive stages of economic activity that share “techni-

cal or physical aspects” was justifiable and presumptively lawful while the inte-

gration of stages that lack these aspects was at best dubious and arguably

anticompetitive.5 Consider, for example, the vertical integration of a blast

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 133

Economics and Organization: A Primer

furnace and rolling mill on the one hand, and the efforts by manufacturers to

prohibit franchisees from selling branded product to unauthorized dealers on the

other. Because technical or physical aspects were held to be present for the first

of these (in the form of thermal economies) but absent for the second, the inte-

gration of blast furnace and rolling mill was declared to be efficient and unobjec-

tionable while the contractual restrictions were held to be unlawful. But are

those conclusions correct?

Technology Transfer

If technology is largely determinative, then blueprints, formulas, and

technical specifications and procedures will describe how to make a good or

service and trained engineers will be able to transfer technology easily by having

the technology described to them. If, however, the world of organization often

entails “tacit judgments” and “unspecifiable skills,”6 then we will not be

surprised to learn that:

The attempt to analyze scientifically the established industrial arts has every-

where led to similar results. Indeed even in the modern industries the indefinable

knowledge is still an essential part of technology. I have myself watched in Hun-

gary a new, imported machine for blowing electric lamp bulbs, the exact counter-

part of which was operating successfully in Germany, failing for a whole year to

produce a single flawless bulb.7

Bigger Is Better

If organization is unimportant, then large firms will be able to do every-

thing that a collection of small firms can do and more. The large firm will do

everything as well as a small firm by replicating small firm practices where small

firms do well. And because the large firm can use hierarchy to improve upon the

occasional breakdowns that occur when relations between autonomous firms

get out of alignment, the large firm will occasionally do better. By intervening

only when expected net gains can be projected—and otherwise managing in a

hands-off fashion—the large firm will never do worse (under replication) and

will sometimes do better (under selective intervention).

Indeed, Tenneco, Inc. evidently had such a program in mind when it

acquired Houston Oil and Minerals Corporation late in 1980. Tenneco “agreed

to keep Houston Oil intact and operate it as an independent subsidiary” and

to preserve aggressive incentive compensation practices in Houston that were

not used elsewhere in Tenneco.8 As it turned out, those promises were not kept

and by October 1981 Tenneco “had lost 34% of Houston Oil’s management,

25% of its explorationists, and 19% of its production people, making it impossi-

ble to maintain it as a distinct unit.”9 Given the impeccable logic of combining

replication and selective intervention, what went wrong?

134 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

Threats

If firms and individuals do not know what is good for them, then we

must tell them what is good for them and support it with threats. Mikhail Gor-

bachev, late in his career as Premier of the former Soviet Union, advised U.S.

firms to “invest now,” rather than wait. He further supplied the following carrot-

and-stick reasoning: “Those [companies] who are with us now have good pros-

pects of participating in our great country [whereas those who wait] will remain

observers for years to come—we will see to it.”10 Accustomed, as he was, to

awarding political favors and penalties to a captive population, Gorbachev

thought that this same reasoning applied quite generally. U.S. firms did not

comply. What went wrong?

Redistribution

If organization does not matter, then we can advise politicians on the

merits of redistribution schemes by comparing actual practices with a hypotheti-

cal ideal. For example, George Stigler described the standard economic evalua-

tion of the sugar program in the U.S. (which is a highly convoluted, politicized,

and controversial program) as follows:

The United States wastes (in ordinary language) perhaps $3 billion per year pro-

ducing sugar and sugar substitutes at a price two to three times the cost of import-

ing the sugar. Yet that is the tested way in which the domestic sugar-beet, cane,

and high fructose-corn producers can increase their incomes by perhaps a quarter

of the $3 billion—the other three quarters being deadweight loss. The deadweight

loss is the margin by which the domestic costs of sugar production exceed import

prices.11

The usual interpretation is that such deadweight losses represent ineffi-

ciency. Accordingly, politicians are routinely advised by economists to discon-

tinue such subsidies or, if benefits must be awarded to favored constituents, to

replace convoluted mechanisms by more efficient direct payments. Bad enough

that politicians should resort to redistribution, but to use inefficient mechanisms

is unacceptable. Politicians, however, routinely refuse good advice. Why are

politicians so dense?

Transaction Cost Economics

Transaction cost economics differs from both economic orthodoxy and

from more behavioral approaches to the theory of the firm. In contrast with the

former, transaction cost economics holds that organizations not only matter but

that they are susceptible to analysis.12 By contrast with the latter, transaction

cost economics uses a combined economics and organization approach to the

study of firms and markets.

Transaction cost economics is

a comparative institutional approach to economic organization, in which

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 135

Economics and Organization: A Primer

technology is de-emphasized in favor of organization, and

the economizing action resides in the details of transactions and the

mechanisms of governance.

These three elements are then combined to yield

a predictive theory of economic organization in which a large number of

apparently dissimilar phenomena are shown to be variations on a few key

transaction cost economizing themes.

There are four main features to these elements: comparative institutions,

economizing, details, and prediction.

Comparative Institutions

Transaction cost economics is always and everywhere an exercise in

comparative institutional analysis. One form of organization is always, therefore,

compared with one or more alternative forms of organization for accomplishing

a given task. The relevant alternatives, moreover, are always feasible (as opposed

to hypothetical). Inasmuch as all feasible alternatives are flawed, it becomes

important to establish the strengths and weaknesses of each.

As opposed to the earlier tradition of invoking flawless government

regulation as the standard remedy for “market failures,” the comparison now

becomes one of flawed markets with flawed regulation. Understandably, regula-

tion does not always win in this comparison, but sometimes it does.13 Ascertain-

ing when net gains will be realized by resorting to (flawed) regulation and when

transactions are better left in the (flawed) market thus entails tradeoffs. More

generally, the symmetrical study of failures goes beyond market failure to

include failures of long-term contracting, failures of bureaucracy, failures

of regulation, and failures of government bureaus.

The upshot is that all forms of organization deserve respect, but none

warrants undue respect. Accordingly, the appropriate test of “failures” of all

kinds—markets, bureaucracies, redistribution—is that of remediableness: an

outcome for which no feasible superior alternate can be described and implemented with

net gains is presumed to be efficient.

Economizing

Transaction cost economics works out of an economizing perspective in

which organization is featured and farsighted but incomplete contracting is projected.

The parties to commercial contracts are thus held to be perceptive about the

nature of the contractual relations of which they are a part, including an aware-

ness of potential contractual hazards. However, because complex contracts are

unavoidably incomplete—it being impossible or prohibitively costly to make

provision for all possible contingencies ex ante—much of the relevant contrac-

tual action is borne by the ex post structures of governance.

136 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

Such an approach to the study of economic organization can be

contrasted with the more usual effort to concentrate all of the contacting action

in the ex ante incentive alignment stage of the contract (which is in the agency

theory tradition). Organizations are important under the transaction cost eco-

nomics setup, but they are irrelevant to agency theory precisely because these

two differ on the matter of contractual completeness.

What the legal philosopher Lon Fuller has described as the study of

“good order and workable arrangements”14 and the institutional economist

John R. Commons has described as the combined study of “conflict, mutuality,

and order”15 are very in the spirit of governance. Not only do both statements

emphasize the importance of order, which is what ex post governance is all

about, but Fuller emphasizes workability (feasible forms of organization) and

Commons invites us to think about governance as the instrument by which order

is accomplished in an incomplete contracting relation where potential conflict

threatens to undo or upset opportunities to realize mutual gains. These are very

different conceptions of the problem of economic organization than is contem-

plated by the firm-as-production function construction.

Coase introduced the idea of transaction costs as a response to this

new conception, but the operationalization of transaction costs poses formid-

able difficulties. A key concept in the effort to operationalize transaction costs

was to treat adaptation as the central problem of economic organization, of

which two kinds—autonomous adaptation and cooperative adaptation—were

distinguished. Upon reformulating the problem of economic organization as one

of adaptation, it became natural to describe transaction costs as the (compara-

tive) costs of maladaptation.

Two comparisons were needed. How do different transactions compare

in terms of their needs for autonomous and cooperative adaptation? How do

markets, hierarchies, and other modes of governance compare as instruments

for effecting adaptations of both kinds? Prescribing governance structures so as

to effect cost-effective relief against maladaptation hazards became the recurrent

theme. The test, of course, was in the eating: Do the data support the predicted

alignments between transactions and governance? The results are now in:

they do.17

Details

Although Tjalling Koopmans declared that “the task of linking concepts

with observations demands a great deal of detailed knowledge of the realities

of economic life,”16 that is a message that many economists have been loathe to

concede. Operating, as it does, at a high level of generality, the orthodox theory

of the firm appears to make it unnecessary to study the scruffy transactional and

organizational details of economic life.

To be sure, economic orthodoxy deserves a great credit for explicating

how a particular type of spontaneous mechanism—the market—accomplishes

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 137

Economics and Organization: A Primer

price and output determination. The abiding interest of orthodoxy in the marvel

of the market was not, however, matched by a parallel interest in the marvel

of hybrids and hierarchies, especially as these relate to cooperative adaptations.

Orthodox assumptions that property rights are well defined and that contracts

are costlessly enforced by well-informed courts reinforce this neglect of transac-

tional and organizational detail.

Transaction cost economics supplants a preoccupation with the market

with a symmetrical interest in all forms of organization. Hence the details of

transactions and of alternative modes of governance become significant. Con-

trary to the “legal centralism” tradition, according to which “disputes require

‘access’ to a forum external to the original social setting of the dispute [and that]

remedies will be provided as prescribed in some body of authoritative learning

and dispensed by experts who operate under the auspices of the state,”18 trans-

action cost economics holds that in “many instances the participants can devise

more satisfactory solutions to their disputes than can professionals constrained

to apply general rules on the basis of limited knowledge of the dispute.”19 Private

ordering through ex post governance is therefore where the main action resides.

The study of markets and of prices and quantities thus gives way to

the study of transactions and of alternative modes of governance, with special

emphasis on the mechanisms of intertemporal contracting.20 Not only do stu-

dents of comparative economic organization often need to have first-hand

knowledge about the phenomena in question, but the data needs are very dif-

ferent. Unable to work off of census and financial reports, students of organiza-

tion now need to collect original data that bear directly on the issues.

Prediction

The main purpose of science is understanding rather than prediction.21

Because, however, there are many plausible theories or would-be theories, it is

important to sort the wheat from the chaff.

That is accomplished by asking each to

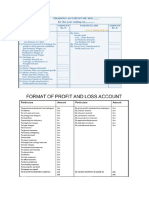

FIGURE 1. Simple Contracting Schema show its hand. What are the predictions?

What do the data support?

The basic hypothesis out of which

A

transaction cost economics works is that

h=0 of discriminating alignment: transactions,

which differ in their attributes, align with

governance structures, which differ in

B their cost and competence, so as to effect

s=0

a transaction cost economizing outcome.

h>0

The simple contractual schema in Figure 1

illustrates some of the main points. For

s>0 example, let us assume that there are two

C ways to supply a good or service to a par-

ticular customer’s needs. One is by using

138 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

general purpose labor and equipment; the other is to make specialized invest-

ments in support of the customer’s distinctive needs. The use of general purpose

assets poses negligible hazards (hence is designated h = 0) since, if the contract

should break down, these assets could easily be redeployed to alternative pro-

ductive uses. By contrast, the use of special purpose assets poses real hazards

(designated h > 0), since specialized investments cannot be redeployed without

loss of productive value.

The buyer who asks his supplier to make specialized investments on his

behalf has two options. One option is to ask the supplier to take his chances that

the contract will work out well (s = 0). The second is to introduce safeguards

that deter breach and promote continuity should the contract experience trouble

during execution (s > 0). For example, the buyer could post a bond that could

be forfeited in the event of breach. Or the buyer and supplier could create

information disclosure and specialized dispute settlement mechanisms (such

as arbitration), the purposes of which are to permit the parties to get through

a contractual impasse and to get on with the job.

Node A in Figure 1 is the “ideal” transaction in law and economics,

whereby neither party is dependent on the other (h = 0) and competition pre-

vails. Nuts and bolts, standard steel plate, copper wire, warehouse commodities

more generally are all of this kind—which is to say that economic orthodoxy

applies to a lot of transactions.

The case, however, where the goods or services are supported by special-

ized investments or otherwise pose hazards (h > 0) is more interesting. Node B is

the case where hazards are present (h > 0) but no safeguard is provided (s = 0),

whence the perceptive supplier will charge a risk premium. Buyers that lack a

good track record (perhaps because they are new) are unwilling to post a bond

and/or ar unable to signal security in other respects, yet ask a supplier to special-

ize to their needs are located at Node B. By contrast, Node C is the credible

commitment mode where hazards are present (h > 0) but are mitigated by the

creation of safeguards (s > 0). Clearly the supplier will offer to supply at a lower

price at Node C than at Node B.

One of the lessons of this simple schema is that contracts should be

thought of as a triple in which price, the attributes of the transaction, and con-

tractual safeguards are all determined simultaneously. The latter two are trans-

action cost economics supplements to the more familiar neoclassical concept of

contract as mediated by price.

The above has obvious relevance to the make-or-buy decision. If the firm

has needs for a generic good or service, market transactions (Node A) can be

expected to work well. As transactions become more firm-specific, however,

contractual hazards are posed for which cost-effective mitigation is needed.

More complex modes of long-term contracting thus begin to take shape. In the

limit, firms take transactions out of the market entirely and produce to their

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 139

Economics and Organization: A Primer

own needs. The prediction, therefore, is that “make” eventually supplants “buy”

as contractual hazards build up.

This same schema applies also to the organization of labor market trans-

actions (especially to an examination of the efficiency benefits of labor unions),

the decision to use debt rather than equity to finance a project, the purposes

that are served by a board of directors (and what constituencies should be

awarded votes on the board), and when deregulation will work well and when

poorly. The data, moreover, are broadly congruent. As compared with the usual

explanations for nonstandard and unfamiliar forms of organization (which rely

on monopoly, risk aversion, and/or muscle), the predictions of transaction cost

economizing are relatively powerful. Less tortured explanations for complex and

puzzling phenomena thereby obtain.

Applications

Let us now return to the puzzles described previously and examine them

through the lens of transaction cost economics.

Vertical Market Structures

The technological tradition holds that vertical integration and vertical

market restrictions could often be justified if special “physical or technical

aspects” were associated with successive stages of production or distribution, but

that integration and contractual restrictions that lacked such aspects were pre-

sumptively anticompetitive. The unified ownership of blast furnace and rolling

mill was thus justified because thermal economies were realized in this way. By

contrast, the application by manufacturers of resale restrictions to franchisees

was prohibited because the requisite technological conditions were not satisfied.

Transaction cost economics takes exception with both parts of the argument.

Because transaction cost economics proceeds comparatively, the question

is what form of contracting is best suited to support the governance needs of

blast furnace and rolling mill. Given that thermal economics will be realized by

physically siting these two stages near to each other does not necessarily warrant

common ownership of both stages. In principal, each stage could remain inde-

pendent and the relation between them mediated by contract. If unified owner-

ship is preferred to contracting, that is not because thermal economies are

available to the former and not to the latter. Rather, it is that siting these two

facilities in a cheek-by-jowl relation to each other gives rise to a condition of

bilateral dependency to which contractual hazards accrue if the two stages are

separately owned. The advantage of unified ownership, then, is that it relieves

these hazards and thereby facilitates adaptive, sequential responses to distur-

bances in a more cost effective way.

In effect, the blast furnace and rolling mill are making specialized invest-

ments in support of each other (h > 0). Absent specialized governance

140 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

safeguards, the two parties will be operating at Node B, which is a high cost

node because contracts will frequently break down. The advantage of unified

ownership (Node C) is that the two parties can better harmonize their interests

and adapt coordinately under the auspices of hierarchy. That is a transaction

cost rather than technological rationale.

To be sure, technology can and does complicate the problem of efficient

contracting. The basic analytical need, however, is to assess the efficacy of alter-

native modes of contracting. Technology, by itself, is rarely fully determinative

of organization—which is to say that there are usually several feasible modes of

organization, the choice between which turns importantly on transaction cost

differences. In short, organization matters.

The Schwinn case that was decided in 1967 illustrates the application of

technological reasoning to vertical market restrictions. Schwinn was a bicycle

firm that sold its bicycles through authorized dealers. Although Schwinn

franchisees were permitted to carry other bicycles, Schwinn prohibited its fran-

chisees from selling Schwinn bicycles to unauthorized dealers. The government

declared that such restrictions were unlawful because there was no special phys-

ical or technical aspect between Schwinn and its franchisees. Indeed, the gov-

ernment further opined that:

Either the Schwinn bicycle is in fact a superior product for which the consumer

would willingly pay more, in which event it should be unnecessary to create a

quality image by the artificial device of discouraging competition in the price of

distributing the product; or it is not of premium quality, and the consumer is

being deceived into believing that it is by its high and uniform retail price. In

neither event would the manufacturer’s private interest in maintaining a high-

price image justify the serious impairment on competition that results.22

A very different interpretation emerges when the Schwinn case is exam-

ined in comparative contractual terms.23 Upon looking not at physical ties but

on asset characteristics, the question is whether Schwinn has created a special-

ized asset that will be put at risk if no contractual restrictions are permitted. A

plausible argument can be made that Schwinn has created a specialized asset

(brand name capital), the value of which would be compromised if the Schwinn

bicycle is sold by unauthorized dealers.

In effect, the government was assuming that Schwinn was engaged in

Node A transactions, for which restrictions are unneeded because h = 0. In fact,

however, Schwinn had created a specialized asset (h > 0), whence the relevant

choices were Node B or Node C. By prohibiting any restrictions (safeguards),

the government was denying Schwinn the benefits of Node C and locating it

on Node B. As discussed above, Node B is a high cost (and, more generally,

inefficient) mode.

Because, moreover, the U.S. bicycle market was competitively organized,

the claims by the government of anticompetitive monopoly abuse (high and

uniform retail pricing) were fanciful. The government nevertheless proceeded,

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 141

Economics and Organization: A Primer

under the prevailing technological/inhospitality tradition, to argue vigorously

against Schwinn, and the 1967 Supreme Court declared that the Schwinn

restrictions were unlawful.24

Technology Transfer

Some words become obsolete or describe imaginary conditions, but “inef-

fable”—incapable of being expressed in words— is not one of them. Tacit knowl-

edge—of which the Chinese proverb that a picture is worth a thousand words

and the idea of learning-by-doing are both manifestations—is a subtle condition

and warrants respect. The “indefinable knowledge” to which Michael Polanyi

refers in his description of industrial arts (and illustrates more generally in his

deeply thoughtful book on Personal Knowledge) is not even contemplated, much

less accommodated, by the technological tradition.

The idea, however, of contract as ex ante framework, in relation to

which ex post governance fills in the details, has broad generality. Faced with

the impossibility or prohibitive cost of attempting to describe a complex tech-

nology with words, blueprints, formulas, and the like, alternative ways of

accomplishing technology transfer—communicating tacit knowledge—warrant

consideration. In particular, the direct involvement of experienced managers,

engineers, and workers in whom the relevant knowledge is deeply embedded

may be needed. Combining human assets in productive teams from which oth-

ers can learn is an organizational response to the technological impasse that is

otherwise posed. Again, organization matters.25

Bigger Is Better

Unless, for some reason, the combination of replication with selective

intervention cannot be implemented as described, then large firms will always

be able to do as well as a collection of small firms and will sometimes do better.

Successive application of that reasoning leads, however, to the counterfactual

prediction that all business will be concentrated in one large firm. Wherein

does the logic break down?

The problem is that both replication and selective intervention are easy

to postulate but difficult, indeed impossible, to implement. That is not evident

upon examining the issue from a technological perspective for a very simple

reason: the action resides in the organizational mechanisms through which these

two processes work.

If firms and markets differ in kind, then those differences need to be iden-

tified and the ramifications worked out. As viewed through the microanalytic

lens of transaction cost economics, the benefits of hierarchy (which mainly take

the form of cooperative adaptation) always come at a cost: not only are incen-

tives unavoidably degraded upon transferring a transaction from market to hier-

archy, but added bureaucratic costs also obtain.26 The limits of firm size puzzle

thus turns out to have organizational rather than technological origins.27 One

142 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

of the lessons is that we need to be much more self-conscious about studying

bureaucracy—which is an important, complex, puzzling, and much neglected

form of organization. A combined economics and organizations approach—

rather than either by itself—is needed.

Threats

The language of power (threats) is understandably attractive when deal-

ing with a captive population. When dealing, however, with investors who have

options, the relevant language is that of credible commitments rather than credi-

ble threats. This is not an easy transformation—witness Mikhail Gorbachev’s

“invitation” to American firms to invest now, and have good prospects, rather

than wait, and have poor prospects, because “we will see to it” that those who

wait will do poorly. If, however, Gorbachev has the latitude to punish his ene-

mies (the laggards), what is to prevent him from deciding to expropriate his

friends (those who invest now) should that suit his purposes once their invest-

ments are in place?

What Gorbachev inadvertently revealed by his words is that investing in

the Soviet Union was hazardous—because politicians were little constrained by

the constitution or an independent judiciary to respect investments. Accordingly,

perceptive investors will make only limited and redeployable investments and

will reserve larger and nonredeployable investments for other political regimes

that are perceived to have superior credible commitment properties.

Rather, therefore, than harangue American business firms to invest now,

Gorbachev and his successors would be better advised to get their political house

in order. Presented with a credible commitment regime, American firms (and

others) will respond with alacrity to the economic opportunities. Confront them,

however, with legal and political hazards and they will turn elsewhere. That is a

straight-forward lesson from transaction cost economics (which features hazards

and their mitigation) but comes much less easily—perhaps is alien to—a more

muscular power perspective. What investors require, but Gorbachev with his

top-down habits could not understand, are credible commitments. Threats are

inimical to that purpose. Organization matters.

Redistribution

If the deadweight losses of the sugar program are remediable, how is it

that Stigler declared that the “sugar program is efficient. This program is more

than fifty years old—it has met the test of time.”28 There are two possibilities:

the losses in question are not remediable, or Stigler is wrong.

Because economists have been neglectful of mechanisms, issues of

remediableness are often glossed over. It is easy to postulate hypothetical mech-

anisms and assume that they can be implemented. It is naive, however, to pre-

scribe corrective mechanisms—of which lump sum transfers are an example

—that cannot be implemented. The lesson of remediableness is that only feasible

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 143

Economics and Organization: A Primer

mechanisms qualify. The need is to describe practicable mechanisms that can

be implemented with net gains. Not only is the latter a much more demanding

microanalytic exercise, but the analysis of issues such as redistribution that are

the product of politics needs to be done in a way that is respectful of politics.

Thus whereas deadweight loss analysis quickly concludes that indirect

and costly mechanisms are inefficient, the contractual approach to politics asks

whether these mechanisms serve intended political purposes. As Terry Moe

makes clear, what sometimes appear to be convoluted mechanisms are often

the means by which political bargains are reached and credibility is assured.29

Absent, therefore, a showing that these mechanisms have broken down, a

judgment of inefficiency is unwarranted. The details, once again, are where

the action resides.

Concluding Remarks

The economics of organization is a huge subject and is usefully examined

from several points of view. A technological perspective in which price and out-

put are featured is one instructive approach, but should not exclude all others.

The transaction cost economics point of view works out of an interdisciplinary

perspective which emphasizes the importance of organization and highlights the

many ways in which the mechanisms of ex post governance contribute to an

economizing result.30 The identification, explication, and mitigation of hazards

is central to this exercise. Indeed, a compact response to the query “Why do we

have so many kinds of organizations?” is this: hazards come in many forms, in

relation to which ex post governance structures need to be aligned in discrimi-

nating ways, thereby to relieve the hazards. To the extent to which our under-

standing of hazards and hazard mitigation is underdeveloped, the teaching and

practice of management will benefit from more self-conscious attention to these

matters. Comparative institutional analysis in which the economic importance

of organization is featured will come to play a larger role in the business school

curriculum if and as there is agreement that “Truly among man’s innovations,

the use of organization to accomplish his ends is among both his greatest and

his earliest.”31

Notes

1. The quotation is attributed to Turner by Stanley Robinson, 1968, N.Y. State Bar

Association, Antitrust Symposium, p. 29.

2. Ronald H. Coase, “Industrial Organization: A Proposal for Research,” in V. R.

Fuchs, ed., Policy Issues and Research Opportunities in Industrial Organization (New

York, NY: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1972), p. 67.

3. Herbert Simon, “Theories of Decision Making in Economics and Behavioral Sci-

ence,” American Economic Review, 49 (June1959): 253-258; Herbert Simon, “New

Developments in the Theory of the Firm,” American Economic Review, 52 (March

1962): 1-15.

144 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

Economics and Organization: A Primer

4. Richard M. Cyert and James G. March, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963).

5. Joe Bain, Industrial Organization, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons,

1968), p. 381.

6. Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (New York,

NY: Harper & Row, 1962), p. 52.

7. Ibid., p. 206.

8. George Getschow, “Loss of Expert Talent Impedes Oil Finding By New Tenneco

Unit,” Wall Street Journal, February 9, 1982.

9. Ibid.

10. Quoted in International Herald Tribune, “Soviet Economic Development,” June 5,

1990, p. 5.

11. George J. Stigler, “Law or Economics?” Journal of Law and Economics, 35 (October

1992): 459. Note, however, that Stigler takes vigorous exception with this inter-

pretation.

12. R. C. O. Matthews, “The Economics of Institutions and the Sources of Economic

Growth,” Economic Journal, 96 (December 1986): 903-918.

13. Ronald H. Coase, “The Regulated Industries: Discussion,” American Economic

Review, 54 (May1964): 195.

14. Lon L. Fuller, “The Forms and Limits of Adjudication,” Harvard Law Review, 92

(1978): 353-409.

15. John R. Commons, “The Problem of Correlating Law, Economics, and Ethics,”

Wisconsin Law Review, 8 (1932): 3-26, 4.

16. Tjalling Koopmans, Three Essays on the State of Economic Science (New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1957), p. 145.

17. Peter Klein and Howard Shelanski, “Empirical Research in Transaction Cost Eco-

nomics: A Review and Assessment,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 11

(1995).

18. Marc Galanter, “Justice in Many Rooms: Courts, Private Ordering and Indigenous

Law,” Journal of Legal Pluralism, 19 (1981): 1.

19. Ibid., p. 4.

20. If organizations predictably undergo intertemporal transformations and/or are

subject to path dependency, what are these and what are the ramifications? If

large firms are prone to bureaucratization, what are the processes and what are

the lessons? If politics is sometimes an integral and intentional part of the exer-

cise, how do we make provision for that?

21. Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, The Entropy Law and Economic Process (Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), p. 37.

22. Brief for the United States at 26, United States v. Arnold, Schwinn & Co., 388 U.S. 365

(1967).

23. Oliver E. Williamson, “Assessing Vertical Market Restrictions,” University of Penn-

sylvania Law Review, 127 (April 1979): 953-993.

24. The Supreme Court reversed this result in Continental TV Inc. et al. v. GTE Sylvania

Inc. 433 U.S. 36 (1977).

25. David J. Teece, “Profiting From Technological Innovation,” Research Policy, 15

(December 1986): 285-305.

26. Oliver E. Williamson, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (New York, NY: Free

Press, 1985), Chapter 6.

27. The puzzle was first posed in the 1920s by Frank Knight, Risk, Uncertainty, and

Profit (New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1965)

28. Stigler, op. cit., pp. 455-468.

CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996 145

Economics and Organization: A Primer

29. Terry Moe, “The Politics of Structural Choice: Toward a Theory of Public Bureau-

cracy,” in Oliver Williamson, ed., Organization Theory (New York, NY: Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 1990), pp. 116-153.

30. Oliver E. Williamson, The Mechanisms of Governance (New York, NY: Oxford Univer-

sity Press, 1995), Chapter 8.

31. Kenneth J. Arrow, Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing (Chicago, IL: Markham,

1971), p. 224.

146 CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW VOL. 38, NO. 2 WINTER 1996

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A Study On Buying Behavior of Teenagers in Kannur DistrictDocument5 pagesA Study On Buying Behavior of Teenagers in Kannur DistrictEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2 - Understanding Summary of Case Study 2: Navigate The Stages of Enterprise Architecture MaturityDocument3 pagesCase Study 2 - Understanding Summary of Case Study 2: Navigate The Stages of Enterprise Architecture MaturitySantosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Operating CostingDocument12 pagesIntroduction To Operating CostingsachinNo ratings yet

- RICO KP-603 Food FactoryDocument1 pageRICO KP-603 Food FactoryUjjal Kumar BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Managerial CompetenciesDocument49 pagesManagerial CompetenciesJagannath Shashank Vadrevu100% (1)

- Applied Value Investing (Renjen, Oro-Hahn) FA2015Document4 pagesApplied Value Investing (Renjen, Oro-Hahn) FA2015darwin12No ratings yet

- Ceat B - SDocument2 pagesCeat B - SRashesh GajeraNo ratings yet

- Tariq Shahzad Acca: Employment History Executive ProfileDocument1 pageTariq Shahzad Acca: Employment History Executive ProfileMurtaza JangdaNo ratings yet

- Article of CVPDocument6 pagesArticle of CVPSajedul AlamNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Social Networks in The Development of SportsDocument23 pagesThe Impact of Social Networks in The Development of SportsMihaela MaresoiuNo ratings yet

- Innovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesInnovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer SatisfactionmonicaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Consumer Buying Behaviour in Retail Readymade Garment ShopsDocument2 pagesA Study On Consumer Buying Behaviour in Retail Readymade Garment ShopsATSx room clashNo ratings yet

- Foundations Order FlowDocument27 pagesFoundations Order FlowpsmadhusudhanNo ratings yet

- ABE Information SlideDocument23 pagesABE Information SlideAudriNo ratings yet

- Mckinsey-Full Article 25 PDFDocument7 pagesMckinsey-Full Article 25 PDFjcmunevar1484No ratings yet

- Assignment Cost Final Edition1Document5 pagesAssignment Cost Final Edition1Bekama Abdii Koo TesfayeNo ratings yet

- Coa C2014-002 PDFDocument49 pagesCoa C2014-002 PDFDivina Grace Ugto SiangNo ratings yet

- "From Startup To Scalable Enterprise Laying The Foundation" PDFDocument9 pages"From Startup To Scalable Enterprise Laying The Foundation" PDFshizzyNo ratings yet

- Zimnisky Global Rough Diamond Price Index - Paul Zimnisky - Diamond Industry AnalysisDocument3 pagesZimnisky Global Rough Diamond Price Index - Paul Zimnisky - Diamond Industry AnalysisBisto MasiloNo ratings yet

- Social Enterprise and Development Process - TourismDocument86 pagesSocial Enterprise and Development Process - TourismRommel Añonuevo NatanauanNo ratings yet

- PM January 2021 Lecture 4 Worked Examples Questions (Drury (2012), P. 451, 17.17)Document6 pagesPM January 2021 Lecture 4 Worked Examples Questions (Drury (2012), P. 451, 17.17)KAY PHINE NGNo ratings yet

- Final AccountsDocument4 pagesFinal AccountsMayuri More-KadamNo ratings yet

- Case Studies of Stress ManagementDocument9 pagesCase Studies of Stress Managementrgrgupta002No ratings yet

- MOU - PadmalochanaDocument4 pagesMOU - PadmalochanaBoopathy RangasamyNo ratings yet

- System of Dabbawalas and Their PillarsDocument3 pagesSystem of Dabbawalas and Their PillarsAnkita SinhaNo ratings yet

- Project Report: "Role of Sales Promotion On FMCG"Document27 pagesProject Report: "Role of Sales Promotion On FMCG"Pijush RoyNo ratings yet

- SAP Case Study TemplateDocument105 pagesSAP Case Study TemplateJo KeNo ratings yet

- Ryan Air CaseDocument4 pagesRyan Air Casedfglbld0% (1)

- Systems Engineering Manager Medical Devices in Denver Boulder CO Resume Martin CoeDocument3 pagesSystems Engineering Manager Medical Devices in Denver Boulder CO Resume Martin CoeMartinCoeNo ratings yet

- I. Agreement: HE Following Are The Points Are The Points of Difference Between Partnership and Co-OwnershipDocument3 pagesI. Agreement: HE Following Are The Points Are The Points of Difference Between Partnership and Co-OwnershipOsama Abdur RahimNo ratings yet