Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ottomans in The Balkans PDF

Ottomans in The Balkans PDF

Uploaded by

Sm0k3yBoyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ottomans in The Balkans PDF

Ottomans in The Balkans PDF

Uploaded by

Sm0k3yBoyCopyright:

Available Formats

'Journals (Die Gartenlaube, Die Grenzboten, a n d Westermann's J a h r b u c h ) which the

a u t h o r consulted for t h e period 1860 to 1880. After an initial discussion o f the journals

a n d their main c o n t r i b u t o r s , there is a careful description o f their views on the Slavs,

on Pan Slavism, o n Russia a n d Russian history, on German-Russian relations, and on

o t h e r peoples o f Eastern E u r o p e , n o t a b l y Poles, Czechs, a n d Hungarians.

The result is w h a t t h e a u t h o r calls a case s t u d y in t h e "escalation of misunderstand-

ings" a b o u t Eastern E u r o p e , a n d especially Russia, on t h e part o f literate Germans.

The usual cliches were p e r p e t u a t e d : Slavic " t y p e s " were politically a n d culturally in-

capable o f accomplishing very m u c h ; Pan Slav nationalism was a t h r e a t to civilized

Europe; the Russian government was a colossus a n d a danger; t h e Slavs belonged to Asia,

m o r e t h a n to Europe. But in addition there was a d y n a m i c shift over t i m e t h a t cor-

responded to Bismarck's unification o f G e r m a n y u n d e r Prussia: t h e reforms of Tsar

Alexander II a n d t h e Polish uprising o f 1863 generated new fears o f a Russo-Austrian

alliance; t h e Russo-Turkish War o f 1877-78 raised new suspicions a b o u t Slav aggression

in t h e Balkans. The conclusion is t h a t G e r m a n unification elicited an even m o r e negative

view o f an inferior, b u t dangerous, Eastern E u r o p e t h a n h a d existed previously.

U n f o r t u n a t e l y , public opinion appears here mainly as a c o m p e n d i u m o f p r i n t e d state-

m e n t s in three journals. There is n o e x t e n d e d discussion o f the shifting role o f the

political press during t h e period, o f the vegement R u s s o p h o b i a o f Baltic G e r m a n emigres

a n d o t h e r intrest groups, or o f t h e interplay b e t w e e n the press a n d Bismarck's govern-

ment. As a result, t h e a u t h o r has convincingly d e m o n s t r a t e d a growing press hostility

t o w a r d Eastern E u r o p e in G e r m a n y , b u t has n o t fully explained its causes or its mech-

anism.

R o b e r t C. Williams Washington University

Peter F. Sugar. Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. Seattle: Univer-

sity of Washington Press, 1977. xviii, 365 pp. $16.95.

C o n f r o n t i n g negative stereotypes is an occupational hazard all historians o f the Otto-

m a n era m u s t accept. Two o f the most persistent and i m p o r t a n t o f these historical cliches

deal with the i m p a c t o f the Turkish c o n q u e s t a n d subsequent decline u p o n the popula-

tions o f southeastern Europe. With great effort O t t o m a n historians have managed to con-

vince t h e e d u c a t e d public t h a t the Turkish c o n q u e s t o f the Balkans represented some-

thing more substantial t h a n a b o o t y raid by primitive Asiatic tribesman. This same

g r o u p o f scholars has b e e n less successful with the second m y t h afflicting Otto-

m a n history: the Turko-Muslim rulers so mismanaged their huge empire during the cen-

turies o f decline t h a t Balkan p o p u l a t i o n s accepted nationalism in t h e n i n e t e e n t h c e n t u r y

as a c o n s e q u e n c e o f t h e anarchy and disorder o f t h e t w o preceding centuries.

Peter Sugar wrestled with b o t h o f these stereotypes when he set a b o u t organizing the

history o f Southeastern E u r o p e from the t i m e o f t h e O t t o m a n conquests to t h e o u t b r e a k

o f the S e r b i a n r e v o l t i n 1804. Parts I a n d II o f his b o o k contain a description o f t h e origin

o f t h e O t t o m a n s , t h e invasion o f t h e Balkans, a n d the i n t r o d u c t i o n o f O t t o m a n institu-

tions into w h a t Sugar calls the core regions o f O t t o m a n Europe: those provinces t h a t

were administered directly by imperial bureaucrats. In Part III t h e a u t h o r reverses his

Istanbul-centered perspective o f imperial events to examine t h e history o f t h e b o r d e r

provinces o f Moldavia, Wallachia, Transylvania, a n d Dubrovnik from the high water m a r k

o f the Turkish advance t h r o u g h the era o f decline. Part IV takes up t h e story o f decline

in the core provinces, following the chain o f events d o w n t o the final " d i s i n t e g r a t i o n " o f

t h e O t t o m a n provincial system on t h e eve o f t h e n i n e t e e n t h century. In the concluding

section, Sugar discusses t h e cultural life o f t h e Greeks, Slavs, a n d Jews u n d e r t h e T u r k s -

O t t o m a n cultural activity in the Balkans is dismissed as m e a g e r - a n d t h e n offers some

final observations a b o u t the O t t o m a n legacy in t h e Balkans.

Although t h e a u t h o r claims to be presenting a picture o f Balkan life u n d e r the Turks,

he has in fact set o u t to write a b o u t the rise a n d fall o f Ottomans p o w e r in one o f the

most i m p o r t a n t regions o f the empire. It is, therefore, o f interest t o see h o w Sugar han-

dles the history o f t h e Turko-Muslim conquest. A hint o f h o w t r o u b l e s o m e an issue this

will be occurs w h e n we are i n f o r m e d in Part I t h a t the reason t h e Turks converted to a

simple form o f Islam is because t h e y were " n o t yet ready to cope with the theological

difficulties a n d complications of either Judaism or Christianity" (p. 4). What t h e n follows

is a pastiche o f early O t t o m a n history based mainly on Shaw, Inalcik a n d Vryonis. None

o f those historians would wish, however, to be linked with Sugar's n u m e r o u s errors: the

timar was n o t a grant of land (p. 37-38); t h e Mongol empire h a d declined by the fifteenth

c e n t u r y (p. 57); Islam is n o t against the acquisition o f wealth (p. 81), etc. Nor would

they wish to be associated with the oversimplifications Sugar introduces: forced conver-

sion was a typically O t t o m a n practice (p. 31-32); the Turkish conquest was m a d e possi-

ble by the millet system (p. 47). This is n o t to say t h a t Sugar fails t o present some provo-

cative ideas a b o u t the c o n q u e s t ' s i m p a c t u p o n Balkan society. His observation a b o u t t h e

relation b e t w e e n folk Islam, p o p u l a r Christian beliefs, and conversion t o Islam is probably

correct. But this crucial issue, as is the case with m a n y o t h e r o f t h e a u t h o r ' s ideas, does

n o t rest u p o n any d o c u m e n t a t i o n .

This freewheeling speculation a b o u t the O t t o m a n "golden age" reaches a climax at

t h e e n d o f Part II w h e n the a u t h o r concludes t h a t m o s t o f the difficulties the Balkan

Population suffered in t h e centuries o f decline were due to an O t t o m a n overadministra-

tion o f Balkan society during the time o f expansion. This is truly a revolutionary conclu-

sion; for m o s t historians o f O t t o m a n decline p o i n t t o the weakness o f the central admin-

istration as o n e o f t h e main reasons for the increasing m a l t r e a t m e n t o f the subjects. Is

Sugar's conclusion a daring historical hypothesis? I t h i n k not. Since the end o f World

War II the progressive exploitation o f O t t o m a n archival resources has convinced histor-

ians that t h e m o s t influential act the O t t o m a n s p e r f o r m e d in Southeastern E u r o p e was

to impose their administration. What we have here, therefore, is a n e w casting o f the old

negative stereotype. This time it is n o t t h e Turko-Muslim warrior who is the culprit b u t

the O t t o m a n bureaucrat.

If the O t t o m a n s alienated the populations o f t h e Balkans through overadministration

during the golden age, the opposite practice, according to Sugar, is what dominates t h e

two centuries o f decline. Not only did the O t t o m a n administration descend to an "all-

time l o w " by the eighteenth century, b u t also the bureaucracy, army, a n d ruling class

became c o r r u p t . Collapse at the center p r o d u c e d chaos in the provinces where rapacious

local factions c o n t r i b u t e d to t h e growing misery o f the p o p u l a t i o n . After t w o centuries

o f such disorder the Christian p o p u l a t i o n o f Southeastern Europe easily m a d e the tran-

sition from " b a n d i t r y " to national liberation forces on t h e p a t t e r n established by t h e

Serbian revolt o f 1801-04.

This is a very familiar view o f O t t o m a n decline. Long ago challenged, the c a t a s t r o p h e

t h e o r y o f decline has given way to a greater appreciation o f h o w resilient O t t o m a n insti-

stutions were during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As the work o f I t z k o w i t z ,

Inalcik, and m a n y o t h e r historians who have concerned themselves with local history

have established, the imperial administration was able to shift t o a form o f decentralized

rule which fit well within the framework o f O t t o m a n institutions. As Sugar notes, Phan-

ariot rule in the Danubian Principalities intensified the a t t a c h m e n t o f the region to pat-

terns of politics, culture, and administration that were O t t o m a n and n o t national.

If one wishes to u n d e r s t a n d the m o d e r n course o f events in Southeastern Europe, the

history of the O t t o m a n Empire m u s t first be grasped on its o w n terms. In this b o o k Sugar

has n o t m a d e t h a t effort. His understanding o f imperial institutions and objectives is de-

You might also like

- The Decline of The Ottoman EmpireDocument6 pagesThe Decline of The Ottoman EmpireEmilypunkNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Tutorial Activity Sheet2019AutumnDocument3 pagesWeek 5 Tutorial Activity Sheet2019AutumnKhanh NguyenNo ratings yet

- History of The Balkans Vol 1 Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Barbara JelavichDocument419 pagesHistory of The Balkans Vol 1 Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Barbara JelavichMiriam Brait100% (9)

- A History of the Later Roman Empire (Vol. 1&2): From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian - German Conquest of Western Europe & the Age of JustinianFrom EverandA History of the Later Roman Empire (Vol. 1&2): From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian - German Conquest of Western Europe & the Age of JustinianNo ratings yet

- ADANIR, F. Balkan Historiography Related To The Ottoman Empire Since 1945Document9 pagesADANIR, F. Balkan Historiography Related To The Ottoman Empire Since 1945Mariya KiprovskaNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Decline ThesisDocument4 pagesOttoman Decline Thesisgjgwmp01100% (2)

- Burchell and Gray - The American WestDocument22 pagesBurchell and Gray - The American WestgozappariNo ratings yet

- Late Ottoman Rule Over PalestineDocument4 pagesLate Ottoman Rule Over PalestineJuhi MathurNo ratings yet

- ArmatoloiDocument266 pagesArmatoloiAnton Cusa100% (1)

- Lewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomyDocument19 pagesLewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomySeungjune MinNo ratings yet

- CROATIAN NOBLE REFUGEES IN LATE 15th AND 16th CENTURY BANAT - Schmitt - The - Ottoman - Conquest - of - The - BalkansRESEE - 003Document171 pagesCROATIAN NOBLE REFUGEES IN LATE 15th AND 16th CENTURY BANAT - Schmitt - The - Ottoman - Conquest - of - The - BalkansRESEE - 003HenohNo ratings yet

- Spinka Christianity Balkans 1933 PDFDocument208 pagesSpinka Christianity Balkans 1933 PDFlesky17No ratings yet

- Ottoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural ExchangeFrom EverandOttoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural ExchangeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Poggi - The Feudal System of RuleDocument11 pagesPoggi - The Feudal System of RuleMarilyn GNo ratings yet

- Balta Zimmi Muslims PDFDocument8 pagesBalta Zimmi Muslims PDFIrma SulticNo ratings yet

- The Academy of Political Science Political Science QuarterlyDocument24 pagesThe Academy of Political Science Political Science QuarterlyanitaNo ratings yet

- UES Hobsbawm The Courious History of Europe 1996Document18 pagesUES Hobsbawm The Courious History of Europe 1996Q100% (1)

- Turkey Turkey 00 Clar RichDocument574 pagesTurkey Turkey 00 Clar RichAbdurrahman ŞahinNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Historiography and The SeventeenDocument25 pagesOttoman Historiography and The SeventeenEmri MbiemriNo ratings yet

- The Lands of St Peter: The Papal State in the Middle Ages and the Early RenaissanceFrom EverandThe Lands of St Peter: The Papal State in the Middle Ages and the Early RenaissanceNo ratings yet

- (Ukrainian Studies) Gwendolyn Sasse-The Crimea Question-Harvard University Press (2007)Document369 pages(Ukrainian Studies) Gwendolyn Sasse-The Crimea Question-Harvard University Press (2007)ismetjaku100% (2)

- (Cambridge Texts in The History of Political Thought) Michael Bakunin - Statism and Anarchy (2005, Cambridge University Press) PDFDocument297 pages(Cambridge Texts in The History of Political Thought) Michael Bakunin - Statism and Anarchy (2005, Cambridge University Press) PDFEhsan TabariNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Decline ThesisDocument8 pagesOttoman Empire Decline Thesisheatherharveyanchorage100% (2)

- Research Paper Ottoman EmpireDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Ottoman Empireaflbqewzh100% (1)

- Catholic Missions and Local Rulers in Su PDFDocument29 pagesCatholic Missions and Local Rulers in Su PDFAlexNo ratings yet

- Medieval Medieval: Bryce Lyon Bryce LyonDocument3 pagesMedieval Medieval: Bryce Lyon Bryce Lyonmiroslavbagnuk2No ratings yet

- A Tale of Three EmpiresDocument27 pagesA Tale of Three EmpiresSandeep BadoniNo ratings yet

- Geopolitics TriumphDocument17 pagesGeopolitics TriumphAriel RadovanNo ratings yet

- The Thirteenth Tribe by Arthur KoestlerDocument101 pagesThe Thirteenth Tribe by Arthur Koestlerextemporaneous93% (15)

- The Place of The Young Turk Revolution IN Turkish HistoryDocument17 pagesThe Place of The Young Turk Revolution IN Turkish Historycalibann100% (2)

- A Greek Démarche On The Eve of The Council of Florence 1975Document16 pagesA Greek Démarche On The Eve of The Council of Florence 1975LulamonNo ratings yet

- Kane 2020Document3 pagesKane 2020Cho KarinNo ratings yet

- From Antiquity To The Middle Ages 31bc - Ad 900Document83 pagesFrom Antiquity To The Middle Ages 31bc - Ad 900Witt Sj100% (3)

- Jerry H. BentleyDocument23 pagesJerry H. BentleyUroš DakićNo ratings yet

- The Price Revolution of The Sixteenth Century - BarkanDocument27 pagesThe Price Revolution of The Sixteenth Century - BarkanhalobinNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Essay ThesisDocument4 pagesOttoman Empire Essay Thesisirywesief100% (2)

- Anti-Turkish Movements in Macedonia Before The 1821 Greek RevolutionDocument22 pagesAnti-Turkish Movements in Macedonia Before The 1821 Greek RevolutionMakedonas AkritasNo ratings yet

- Panslavism PDFDocument109 pagesPanslavism PDFVMRONo ratings yet

- Holding The World in Balanc PDFDocument28 pagesHolding The World in Balanc PDFRafael DíazNo ratings yet

- The Differing Perceptions of The Ottomans in Bulgarian, Greek and Turkish MemoryDocument32 pagesThe Differing Perceptions of The Ottomans in Bulgarian, Greek and Turkish MemoryAli PolatNo ratings yet

- Disputes Over Great Moravia: Chiefdom or State? The Morava or The Tisza River?Document20 pagesDisputes Over Great Moravia: Chiefdom or State? The Morava or The Tisza River?Gosciwit MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- Teszelszky SummaryDocument2 pagesTeszelszky SummaryKees TeszelszkyNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Population RecordsDocument39 pagesOttoman Population Recordsfauzanrasip100% (1)

- AyannnDocument14 pagesAyannnAlim NasirovNo ratings yet

- Michael A. Reynolds - Buffers, Not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in The First World War and The Myth of PanturanismDocument43 pagesMichael A. Reynolds - Buffers, Not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in The First World War and The Myth of PanturanismSibiryaKurdu100% (1)

- Dimitri Korobeinikov - Bizantium SeljukDocument4 pagesDimitri Korobeinikov - Bizantium SeljukZaenal MuttaqinNo ratings yet

- Canbakal, Hülya, On The Nobility"of Provincial Notables, Provincial Elites in The Ottoman Empire, Halcyon Days in Crete V, Rethymno 2005, 39 - 50.Document12 pagesCanbakal, Hülya, On The Nobility"of Provincial Notables, Provincial Elites in The Ottoman Empire, Halcyon Days in Crete V, Rethymno 2005, 39 - 50.غوران ميلوسافيفيتشNo ratings yet

- Constantine the Last Emperor of the Greeks, or the Conquest of Constantinople by the TurksFrom EverandConstantine the Last Emperor of the Greeks, or the Conquest of Constantinople by the TurksNo ratings yet

- Articol PDFDocument15 pagesArticol PDFbasileusbyzantiumNo ratings yet

- Thomas of Spalato & MongolsDocument28 pagesThomas of Spalato & MongolsstephenghawNo ratings yet

- Thematic Work GroupsDocument21 pagesThematic Work GroupsApsinthosNo ratings yet

- Creating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksFrom EverandCreating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- A Tale of 3 EmpiresDocument28 pagesA Tale of 3 EmpiresVamsi VNo ratings yet

- The Turkish Yoke Revisited The Ottoman N PDFDocument19 pagesThe Turkish Yoke Revisited The Ottoman N PDFJoeNo ratings yet

- Modren TurkeyDocument298 pagesModren TurkeyKozmoz EvrenNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Albanians and Imperial Rivalry in The BalkansDocument9 pagesOttoman Albanians and Imperial Rivalry in The BalkansBida bidaNo ratings yet

- Southern Europeans and Moors From The Early Modern English Perspective: The Stranger in The Dramatic Production of Shakespeare and DekkerDocument17 pagesSouthern Europeans and Moors From The Early Modern English Perspective: The Stranger in The Dramatic Production of Shakespeare and DekkerYagad MashapatyahNo ratings yet

- Best of BucharestDocument2 pagesBest of BucharestSm0k3yBoyNo ratings yet

- World CookbookDocument82 pagesWorld CookbookSm0k3yBoy100% (1)

- Responsible Travel GuideDocument71 pagesResponsible Travel GuideSm0k3yBoyNo ratings yet

- Wild Walk in Romania - Along The Enchanted Way 15aug14 (C) PDFDocument11 pagesWild Walk in Romania - Along The Enchanted Way 15aug14 (C) PDFSm0k3yBoyNo ratings yet

- History of Romania Manual For Secondary School PDFDocument102 pagesHistory of Romania Manual For Secondary School PDFSm0k3yBoyNo ratings yet

- The Memory of The Romanian Elites PDFDocument12 pagesThe Memory of The Romanian Elites PDFSm0k3yBoyNo ratings yet

- Lecture No 7 10112022 013407pmDocument26 pagesLecture No 7 10112022 013407pmFatimaNo ratings yet

- The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms (1919)Document9 pagesThe Montague-Chelmsford Reforms (1919)Sayed Zameer ShahNo ratings yet

- Different Revolts in The PhilippinesDocument1 pageDifferent Revolts in The PhilippinesgellobeansNo ratings yet

- Paige Gibson Forget EssayDocument2 pagesPaige Gibson Forget Essayapi-645506504No ratings yet

- Chapter 7 and Chapter 11 Reflections-Michael AuzDocument5 pagesChapter 7 and Chapter 11 Reflections-Michael Auzapi-313734066No ratings yet

- NILESHDocument9 pagesNILESHflotocorazonNo ratings yet

- Lowi 2017 CH 6 PDFDocument43 pagesLowi 2017 CH 6 PDFJosefinaGomezNo ratings yet

- 37405-2270052-2 1 47606 1 0 PDFDocument4 pages37405-2270052-2 1 47606 1 0 PDFAliza SheikhNo ratings yet

- Reflection MinsuDocument1 pageReflection MinsuChristian Paul PanlaqueNo ratings yet

- 2023 HTAV Sample Exam - Revolutions - SOURCES BOOK I2k1pwDocument18 pages2023 HTAV Sample Exam - Revolutions - SOURCES BOOK I2k1pwBianca AndersonNo ratings yet

- Philippine HistoryDocument4 pagesPhilippine HistoryCamille OngNo ratings yet

- Social Work Policies Programs and ServicesDocument3 pagesSocial Work Policies Programs and ServicesJohn FranNo ratings yet

- Security Analysis of India's Electronic Voting MachinesDocument25 pagesSecurity Analysis of India's Electronic Voting MachinesSrikanth SinghNo ratings yet

- Living As A Foreigner.Document1 pageLiving As A Foreigner.PIR oTECNIANo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Midterm - SSE 27Document3 pagesActivity 1 - Midterm - SSE 27GlydelNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Peoples, Identity, and Free, Prior, and in Formed Consultation in Latin AmericaDocument4 pagesIndigenous Peoples, Identity, and Free, Prior, and in Formed Consultation in Latin AmericaJuan Camilo Vásquez SalazarNo ratings yet

- 4 Can Meaning Be Fixed Essay - The College Study PDFDocument6 pages4 Can Meaning Be Fixed Essay - The College Study PDFfaisalsaadiNo ratings yet

- Elections 4RDocument6 pagesElections 4Rkayla mNo ratings yet

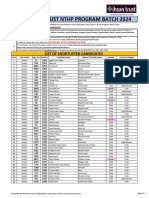

- NTHP Shortlisted List of Candidates For Assessment Test Batch 2024Document149 pagesNTHP Shortlisted List of Candidates For Assessment Test Batch 2024mqasimmxNo ratings yet

- The ManagementDocument14 pagesThe ManagementabmmasukNo ratings yet

- Elder Johnson Appeals Election Results After Runoff LossDocument9 pagesElder Johnson Appeals Election Results After Runoff LossABC News 4No ratings yet

- Virgil Dewain Medlin, The Reluctant Revolutionaries. The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, 1917.Document375 pagesVirgil Dewain Medlin, The Reluctant Revolutionaries. The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, 1917.ventor83No ratings yet

- Ian Buruma - There's No Place Like Heimat by - The New York Review of BooksDocument3 pagesIan Buruma - There's No Place Like Heimat by - The New York Review of BooksBaudelaireanNo ratings yet

- ND 1920Document29 pagesND 1920EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Trends From IGT No.1Document7 pagesPakistan Trends From IGT No.1Khawaja Burhan100% (1)

- Emilio Aguinaldo and Mga Gunita NG HimagsikanDocument24 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo and Mga Gunita NG Himagsikangail de gumanNo ratings yet

- 11 TH - Units and Measurement - 2 (29!08!2020)Document8 pages11 TH - Units and Measurement - 2 (29!08!2020)Aniket ShindeNo ratings yet

- M.sc. Geography, Part-1Document3 pagesM.sc. Geography, Part-1adityasingh.hr15528No ratings yet

- British Relations With The North East IndiaDocument3 pagesBritish Relations With The North East IndiaEmily Grace MukhimNo ratings yet