Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bossink, B. A. - (2007) - Leadership For Sustainable Innovation PDF

Uploaded by

Maria SilviaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bossink, B. A. - (2007) - Leadership For Sustainable Innovation PDF

Uploaded by

Maria SilviaCopyright:

Available Formats

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.

qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 135

International Journal of Technology Management and Sustainable Development

Volume 6 Number 2 © 2007 Intellect Ltd

Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/ijtm6.2.135/1

Leadership for sustainable innovation

Bart A.G. Bossink VU University, Amsterdam

Abstract Keywords

This article explores and explains the effects of a manager’s leadership style on sustainability

sustainable, that is environment friendly, innovation processes. It uses an analyt- sustainable innovation

ical framework, based on the literature, to investigate a manager’s influence on leadership

sustainable innovation in the Dutch building sector. An empirical research project management

observes a manager in a series of sustainable innovation processes in four building building industry

projects. The research shows that a manager’s charismatic, instrumental, strate-

gic, or interactive leadership style substantially contributes to the development of

sustainable innovation processes. It also shows that the exchange of knowledge

and information in the organisation affects the sustainable innovation process. It

concludes that a manager’s performance of an innovation leadership style is

(un)successful where it is (not) combined with the management of knowledge.

Introduction

In many situations, the improvement of the sustainable performance, that

is environmental friendliness, of an organisation means that the organisa-

tion needs to innovate. A manager who wants to guide and steer the sus-

tainable innovation processes has to be, or become, an innovation manager

with substantial leadership competence (cf. Jung et al. 2003; Krause

2004; Lloréns Montes et al. 2005), and a broad repertoire of leadership

skills (cf. Chakrabarti 1974; Roberts and Fusfeld 1981; Kim et al. 1999;

Hauschildt and Kirchmann 2001). However, much of the discussion

focuses on the influence of leadership on innovation, and the body of liter-

ature on a leader’s influence on sustainable innovation processes is not yet

well developed. To contribute to the development of a body of knowledge

in this area, this article investigates the characteristics and effects of lead-

ership on sustainable innovation processes. It concentrates on two basic

research questions:

• What are the characteristics of leadership for sustainable innovation

processes?

• How does leadership affect sustainable innovation processes?

This article provides an analytical framework that enables an in-depth

investigation of a manager’s sustainable innovation stimulating behaviour.

TMSD 6 (2) 135–149 © Intellect Ltd 2007 135

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 136

It introduces an overview of effective sustainable innovation leadership

styles, and offers a set of empirically grounded examples of fits and failures

of innovation leadership.

The article is in six sections. Following this introductory section,

Section 2 reviews the innovation leadership literature. Section 3 explains

the research methodology; Section 4 reports four in-depth case studies of

leadership for sustainable innovation. Section 5 discusses the case studies’

findings. Section 6 draws some conclusions from the discussions of the

paper.

Innovation leadership styles

The literature frequently defines innovation leadership as a manager’s

style, largely influenced by individual behaviour. Repeatedly mentioned

leadership styles in the literature are charismatic (cf. Nadler and Tushman

1990; Stoker et al., 2001), instrumental (cf. Nadler and Tushman 1990;

Eisenbach et al. 1999), strategic (cf. Harmsen et al. 2000; Waters 2000),

and interactive leadership (cf. Burpitt and Bigoness 1997; Eisenbach et al.

1999). This section reviews these styles.

Charismatic leadership

A charismatic leadership style communicates an innovative vision, ener-

gises others to innovate and accelerates innovation processes. Barczak and

Wilemon (1989), and Nadler and Tushman (1990) write that charismatic

leadership generates energy, creates commitment and directs individuals

towards new objectives, values or aspirations. Howell and Higgins (1990)

claim that leadership contributes to the development of new products.

They argue that the charismatic leadership style neglects organisational

boundaries, uses visionary statements and stimulates co-workers’ contri-

butions to renewal. Nonaka and Kenney (1991) state that charismatic

leadership catalyses innovation. It creates a context for selecting the rele-

vant people, and helps them to overcome barriers. This is also emphasised

by Eisenbach et al. (1999). They substantiate that a charismatic leader

develops a vision that is attractive to followers, that considers the underlying

needs and values of the key stakeholders, and is intellectually stimulating.

Instrumental leadership

An instrumental leadership style structures and controls the innovation

processes. Nadler and Tushman (1990) argue that it ensures that the

employees’ activities are consistent with new goals. They conclude that an

instrumental leadership style sets goals, establishes standards, and defines

roles and responsibilities. It creates systems and processes to measure,

monitor and assess results, and to administer corrective action. Nadler

and Tushman (1990), Eisenbach et al. (1999), Norrgren and Schaller

(1999), and Stoker et al. (2001) support these conclusions. In addition to

this, McDonough and Leifer (1986) reason that instrumental leaders use

delineated task boundaries. Barczak and Wilemon’s (1989) conclude that

136 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 137

instrumental leadership heavily relies upon project planning, and inter-

faces between co-innovating departments in the organisation.

Strategic leadership

The person performing the strategic leadership style uses hierarchical

power to innovate. Harmsen et al. (2000) substantiate that managers per-

forming a strategic innovation leadership style know the strategic compe-

tences of the organisation. Waters (2000) concludes that top management

commitment to innovation is a basic characteristic of innovative organisa-

tions. Nam and Tatum (1997), and Eisenbach et al. (1999) argue that a

highly effective strategic innovation leader has the authority to approve

key ideas. Moreover, Norrgren and Schaller (1999) report that a strategic

innovation leadership style facilitates the development of the innovative

capabilities of employees. Managers of innovative companies score rela-

tively high on the aspects commitment, and risk taking. They strategically

commit themselves to innovation, make bold decisions despite the uncer-

tainty of their outcomes and invest in innovation, even when faced with

decreasing profit margins (Saleh and Wang 1993).

Interactive leadership

The interactive leadership style tries to empower employees to innovate

and to become innovation leaders themselves. Eisenbach et al. (1999)

support the conclusion that an interactive innovation leadership style

concentrates on individualised consideration when providing support,

coaching and guidance. Because of this leadership style, employees some-

times develop into innovation leaders who assist the overall leader. Nadler

and Tushman (1990) argue that only exceptional individuals can handle

the behavioural requirements of performing all leadership styles at the same

time. Thus, an effective alternative for leaders who do not combine one or

more styles is to develop leadership throughout the organisation. Rice et al.

(1998), Markham (1998) and Burpitt and Bigoness (1997) draw similar

conclusions. They stress the effectiveness of multiple leadership and

empowered innovation teams.

Research methodology

The research project explores and explains the influence of a manager’s

leadership style on sustainable innovation processes in four cases, and

within the structure of an analytical framework. This section describes the

research design. It introduces the methods to collect and analyse data in

connection with the case studies, and it categorises and defines the ele-

ments of the analytical framework.

Research design

The study consists of four building projects in the Dutch house-building

sector. Each project was innovative in terms of sustainability. The same

municipal manager coordinated all four projects, and performed a distinctive

Leadership for sustainable innovation 137

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 138

leadership style, that is charismatic, instrumental, strategic or interactive

leadership, in each project. An organisation, accredited by the Dutch gov-

ernment, and responsible for the support and evaluation of all sustainable

building projects in the country, monitored and evaluated the projects’

sustainable innovation results.

The projects were the subject of a case study research approach, which

aimed to observe the charismatic, instrumental, strategic and interactive

leadership style of the project manager, and to document and explain the

influence of these styles on the outcomes of the four sustainable building

projects, in real time (cf. Cunningham 1997; Creswell 2003; Yin 2004).

Data collection

A research team observed and documented the building projects, from the

first meeting until the final design meeting. It interviewed the municipal

manager on a regular basis – every two months, over a two-year period. It

observed all official design meetings with the participants in the projects,

that is the rough draft-meetings, the preliminary design-meetings, and the

final design-meetings. In addition to this, it collected and analysed the

rough drafts, preliminary designs and final designs. Table 1 summarises

the interviews, observed meetings and studied documents.

Case Data collection

Charismatic leadership Documents: the schedule of requirements; the final

specifications and plans

Meetings: 3 schedules of requirement-meetings

Interviews: 13 interviews with the municipal manager

Instrumental leadership Documents: 2 feasibility studies; the rough draft; the

preliminary design; the final design; the design

process evaluation report

Meetings: 2 rough draft-meetings; 2 preliminary

design-meeting; 2 final design-meetings;

3 final design-exhibitions

Interviews: 13 interviews with the municipal

manager; 2 interviews with the municipal engineer

Strategic leadership Documents: the rough draft, preliminary design, and

final design for town and country planning;

the design process evaluation report

Meetings: rough draft-meeting; preliminary

design-meeting; final design-meeting

Interviews: 13 interviews with the municipal manager;

an interview with the municipal designer

Interactive leadership Documents: 7 rough drafts; 7 preliminary designs;

7 final designs

Meetings: two rough draft-meetings; 2 preliminary

design-meetings; a final design-meeting

Interviews: 13 interviews with the municipal

manager; 7 interviews with the architects

Table 1: Data collection.

138 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 139

Data analysis

The research project analyses the effects of the leadership styles on sustain-

able innovation processes within the structure of an analytical framework.

Table 2 introduces the basic elements of this framework. It consists of

two parts. The first part translates the literature review into a list of lead-

ership styles. The second part defines the tangible sustainable innovation

processes and results (cf. Bossink 2002). The rationale behind the use

Innovation leadership style Indicator sustainable innovation

Charismatic: The leader is innovation personified: Design processes: new sustainable creation activities

Communicating with vision: The leader informs

employees about the innovation direction;

Energising employees: The leader generates

innovative activity;

Accelerating innovation processes: The leader

speeds up the innovative activity.

Instrumental: The leader uses management

methods to create innovation processes:

Structuring innovation processes: The leader Construction processes: new sustainable

creates systems and processes that produce realisation activities

innovative products and services;

Controlling innovation processes: The leader

establishes and uses goals and measures for

the innovative systems and processes;

Rewarding innovators: The leader gratifies Designs: new sustainable plans and images &

persons who contribute to the innovative

systems and processes.

Strategic: The leader uses his or her position to

create innovation structures and processes:

Using power to innovate: The leader uses the

hierarchical position to authorise innovative

activity and processes;

Committing employees to innovation: The

leader assigns innovative tasks and

responsibilities to subordinates;

Enabling employees to be innovative: The

leader assigns innovative competences

to subordinates.

Interactive: The leader cooperates with other

managers, employees and subordinates:

Empowering innovators: The leader stimulates Objects/areas: new sustainable artefacts and spaces

and allows subordinates to develop and

realise innovative ideas;

Cooperating with innovative employees: The

leader works together with innovators to

develop and realise their innovative ideas;

Developing additional leadership: The leader

teaches others how to be an additional

innovation leader in the innovation processes.

Table 2: The analytical framework.

Leadership for sustainable innovation 139

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 140

of the framework is twofold. It structures the description of the projects’

leadership styles and innovation processes and results. In addition, it

enables a discussion and analysis of the relationship between leadership

styles and the innovation results.

The analytical framework distinguishes between charismatic, instru-

mental, strategic, and interactive leadership styles. It divides each innova-

tion leadership style into three characteristics. The first column of Table 2

defines the innovation leadership styles and their characteristics.

The analytical framework uses two indicators for tangible sustainable

innovation. The indicators are new sustainable processes, and new sus-

tainable products. Furthermore, it divides the indicators into two charac-

teristics. First, it characterises new sustainable processes as new

sustainable design practices and new sustainable construction practices.

Second, it characterises new sustainable products as new sustainable

designs and new sustainable objects/areas. The second column of Table 2

defines the indicators and characteristics of sustainable innovation.

Effectiveness of leadership for sustainable innovation

In each studied project, the municipal manager performed one of the four

leadership styles. Within the structure of the analytical framework, and

for all projects, this section describes the effects of these leadership styles

on the sustainable innovation processes.

Case 1: Charismatic leadership and sustainable innovation

In the first case, the manager coordinated a municipal project to design

and construct various civic facilities with environmentally friendly materi-

als in an urban area of 250 houses. The manager performed a charismatic

leadership style to direct the design activities of a municipal design team,

communicated in visionary images about a sustainable society, and organ-

ised meetings to stimulate the team to discuss various sustainable topics.

The team members complained about the so-called vague ambitions of the

project, the absence of realistic goals and measures and fuzzy manage-

ment. The municipal manager tried to energise the participants, and

invited them to express their visions on sustainable building. They did not

respond and did not develop new ideas. In a last attempt to accelerate the

team members’ contribution, the municipal manager organised meetings

and invited the participants to brainstorm on the specifications of a sus-

tainable design for civic facilities. The project members did not know what

to say and what to do. The overall outcome of the charismatic leadership

style in this project was a completely traditional design, without sustain-

able innovations (see Table 3).

In terms of sustainable building, this project failed. The municipal

manager lacked knowledge of sustainable building, did not absorb useful

information and knowledge during the project, and did not hire internal or

external consultants to inject the project with the knowledge needed. The

manager coordinated a project team, consisting of members without

140 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 141

Innovation leadership style Indicator sustainable innovation

Charismatic leadership: the leader started Design processes: a municipal innovation

to energise project members, then team was responsible for the

communicated with vision, and production of a sustainable design

then accelerated the innovation for civic facilities.

process. Construction processes: -

Designs: -

Objects/areas: -

Table 3: Charismatic leadership and sustainable innovation.

competence in the field of sustainable building, and believed that a charis-

matic leadership style inspired the team members to develop expertise. This

approach had the opposite effect. The team members were not able to trans-

form the manager’s visionary ambitions into practical results. They chose

to blame the manager.

Case 2: Instrumental leadership and sustainable innovation

In the second case, the manager coordinated a municipal project to develop

a green design for an urban area of 500 houses. The municipal manager

led a design team, consisting of architects of a commercial firm and

designers of the municipality. The manager performed an instrumental

leadership style and organised several design meetings. In the meetings, the

design team discussed the transformation of the basic requirements into a

detailed town and country design. In all meetings, the design team evalu-

ated the environmental quality of the preliminary designs. The manager

used a formal planning scheme to assure the quality of each step in the

design process.

During the project, a municipal engineer who also participated in the

project team developed a sustainable system for drainage. The municipal

manager integrated this contribution into the designs of the town and

country project. The overall result of the instrumental leadership style was

a design with many sustainable innovations. It protected the natural envi-

ronment, contained many green areas, and utilised sustainable building

materials (for a specific summary of all sustainable innovations, see Table 4).

In terms of sustainable innovation, the performance of the instrumental

leadership style was successful. The main reasons were that the manager:

• hired three designers from an external architect’s firm with sustainable

competence;

• was assisted by a municipal engineer with relevant sustainable

knowledge;

• defined sustainable project goals;

• selected green building methods;

• introduced checklists for green design; and

• used project management methods to plan, realise, and control the

sustainable building process.

Leadership for sustainable innovation 141

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 142

Innovation leadership style Indicator sustainable innovation

Instrumental leadership: Design processes: (1) an inter-organisational

the leader started to innovation team, consisting of three designers

control the innovation of an architect’s firm, the municipal manager,

processes, and then and a municipal engineer, was responsible for

structured the the preparation of a sustainable town and

innovation process. country design; (2) a municipal engineer

was committed to the design process, and

generated sub-designs to integrate into the

sustainable town and country design.

Construction processes: -

Designs: the process delivered a feasible town and

country design with a high sustainability score.

Sustainable options were integrated in the

design, such as:

• the preservation of existing natural elements

within and around a stream;

• intensive planting of clusters of trees, lawns,

bushes, and other green organisms;

• application of a sophisticated public transport

infrastructure;

• a rainwater preservation system, consisting

of natural streams, wells, drains, and reservoirs;

and

• a car-friendly, but restrictive, and bicycle-

preferring infrastructure.

Objects/areas: the town and country design was

realised with minor alterations.

Table 4: Instrumental leadership and sustainable innovation.

Case 3: Strategic leadership and sustainable innovation

In the third case, the manager coordinated a municipal project to develop

an ecological garden, for an urban area of 50 houses. The manager used a

strategic leadership style and hired a managing designer of an architect’s

firm to develop the design. The manager directed the architect’s activities.

The architect had to adjust the rough draft and preliminary design to the

wishes and demands of the commissioning manager.

The municipal manager showed the rough draft, preliminary design

and final design to a municipal designer. The manager enabled the munic-

ipal designer, who was highly motivated to contribute to the design

process, to develop several sustainable sub-designs and integrate them in

the overall sustainable garden design.

The result of the strategic leadership style was a sustainable garden

design, consisting of many existing, renewed and new natural elements. It

integrated natural elements such as trees, bushes and fields and urban ele-

ments like houses, lanes and playgrounds (for a specific summary of all

sustainable innovations, see Table 5).

142 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 143

Innovation leadership style Indicator sustainable innovation

Instrumental leadership: the Design processes: (1) an inter-organisational

leader started to commit innovation team, consisting of a managing

project members to designer of an architect’s firm, the municipal

innovation, used power manager, and a municipal designer, was

to innovate, and then responsible for the production of a sustainable

enabled project members garden design; (2) the municipal designer was

to be innovative. committed to the design process, and generated

ideas to integrate into the sustainable garden

design.

Construction processes: -

Designs: the project introduced a feasible garden

design with a high sustainability score.

Sustainable options were integrated in the

design, such as:

• preservation of existing green organisms;

• reduction of earth moving;

• connections between green surfaces;

• creation of natural dividing lines between properties;

• planting of bushes and trees with fruit;

• construction of water reservoirs; and

• use of natural material, for instance shells,

gravel, and stones for paving.

Objects/areas: the garden design was realised with

minor alterations.

Table 5: Strategic leadership and sustainable innovation.

In terms of sustainable innovation processes, the performance of a

strategic leadership style was fruitful. The main reasons were that the

municipal manager:

• hired a designer from an external consultant’s firm with sustainable

competence;

• had a municipal designer with knowledge of sustainable gardens; and

• concentrated on directing their activities.

The municipal manager used the power to commit, enable and sometimes

force the designers to develop innovative ideas and solutions.

Case 4: Interactive leadership and sustainable innovation

In the fourth case, the manager coordinated a municipal project to develop

200 environmentally friendly houses. The manager used an interactive lead-

ership style and worked with seven real estate agents, each represented by a

manager. All seven real estate agents coordinated the development of ten to

fifty houses on an area owned by the municipality. The real estate agents and

the municipality agreed that the municipality had to sell the ground to the

real estate agents. It enabled the latter to sell the houses on the commercial

market. Part of this transaction was that the real estate agents allowed

Leadership for sustainable innovation 143

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 144

the municipal manager to co-direct their design processes. As an informal

commissioner, the municipal manager requested the real estate agents to

work with sustainable architects and they all agreed. The municipal manager

convinced the real estate agents and their architects to use environmentally

friendly materials and sustainable design checklists. The manager also organ-

ised workshops to evaluate the designs. All real estate agents and their archi-

tects participated and took notice of each other’s results. Furthermore, the

manager facilitated the architects to act as additional innovation leaders, and

they all did. They developed housing designs with a high sustainability score.

The result of the interactive leadership style in the housing project was a set

of seven highly sustainable designs for ten to fifty houses each (for a specific

summary of all sustainable innovations, see Table 6).

In terms of sustainability, the performance of an interactive leadership

style succeeded. Main reasons were that the municipal manager:

• became an informal commissioner in all project teams;

• convinced all real estate agents to hire a sustainable architect; and

• supported these architects to become innovation leaders.

Leadership styles and knowledge management

The manager’s leadership style and active capability to coordinate the

necessary information and knowledge exchange jointly support the innov-

ativeness of the studied projects. In all cases, the managers showed distinct

leadership styles. In the first case, that is the project that failed, the

manager did not coordinate and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and

information. In each of the other three cases, that is the projects that suc-

ceeded, the manager actively managed the exchange of knowledge and

information between co-workers.

The innovation leadership literature does not explicitly emphasise the

importance of a leader’s efforts to manage knowledge, stimulating sustain-

able information and knowledge exchange. On the other hand, the litera-

ture on knowledge management concentrates on this capability (cf. Lloyd

1996; Grant 1997; Cavaleri and Fearon 2000; Bresnen et al. 2003;

Huang and Newell 2003; Liebowitz and Megbolugbe 2003; Viitala 2004).

Kangari and Miyatake (1997), and Veshosky (1998) argue that infor-

mation gathering is an important innovation driver. In addition to this,

Toole (1998) specifies that a firm’s capacity to gather and process infor-

mation about new technology is a significant stimulator of innovation. In

the failing project, the manager did not collect information about sustain-

ability and sustainable technology. In all three innovative projects, the

manager hired consultants and designers with knowledge of the techno-

logical aspects of sustainable building. Goverse et al. (2001) underpin the

importance of the creation, stabilisation, and upgrading of knowledge net-

works. In the project that failed, the manager did not participate in a

knowledge network, and did not have contacts with universities, research

centres or other knowledge providers. In all three successful projects, the

144 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 145

Innovation leadership style Indicator sustainable innovation

Interactive leadership: the Design processes: (1) 7 inter-organisational

leader started to innovation teams, each team consisting of a

cooperate with realestate agent’s manager, an architect, and

innovative project themunicipal manager, were responsible for

members, and then 10 to 50 sustainable housing designs each;

developed additional (2) themunicipal manager selected architects

leadership in the that could act as additional innovation leaders

organisation. in the design projects, and organised workshops

in which knowledge and ideas were shared.

Construction processes: 7 inter-organisational

innovation teams, each team consisting of a

real estate agent’s manager, an architect, and

the municipal manager, were responsible for

10 to 50 sustainable housing designs each.

Designs: 7 feasible designs for 10 to 50 houses each

with a high sustainability score. All designs

integrated sustainable options, such as:

• orientation of the houses on the sun to use

passive solar energy;

• the use of high-efficiency boilers;

• the use of materials with relatively low embodied

energy or with a high score in a life cycle

analysis;

• improved energy performance of the houses;

• use of large windows on the sun-side to use

passive solar energy;

• use of solar cells for active solar energy;

• use of sustainable paint;

• water efficient showers and toilets;

• use of sustainable timber;

• situating the living rooms at the sun side of the

house;

• isolation of walls, floors, and roofs;

• use of high efficiency glass plates; and

• use of wooden frames.

Objects/areas: all designs were realised with minor

alterations.

Table 6: Interactive leadership and sustainable innovation.

manager had intensive working relationships with several universities,

research centres and consultancy firms. Seaden and Manseau (2001)

argue that collaboration programmes stimulate innovative cooperation

between organisations. All four building projects participated in a national

collaboration programme, funded by the government. The programme

supported the projects’ sustainable ambitions by means of subsidies, infor-

mation and free consultancy. In the unsuccessful project, the manager did

not ask for the programme’s support. In the three highly innovative pro-

jects, the municipal manager contacted the programme’s representatives

and arranged that the projects received subsidies and consultants’ advice.

Leadership for sustainable innovation 145

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 146

According to Nam and Tatum (1992), an integrated and informal

R&D-function strengthens the innovative capability of the organisation. It

creates attention to innovation in parts of the organisation that work

under market conditions. Neither the failing project, nor the successful

projects had an informal R&D-function. The project manager initiated

all innovative action individually, without support of an R&D-function,

R&D-department, or R&D-budget. Toole (1998) concludes that manufac-

turers and retailers of building materials, who provide information about

new products, substantially contribute to innovation in the industry. In

the failing project, the manager did not contact suppliers of sustainable

building materials, and did not search for the necessary information on

new sustainable applications. In the projects that were highly innovative,

the manager hired consultants who had intensive contacts with suppliers

of sustainable building materials. They informed the projects’ designers

about the specifications of sustainable materials. Finally, according to

Veshosky (1998), it is important that the organisation facilitates a project

manager to obtain information about innovation. All projects were part of

the municipal organisation, and the municipality did not provide extra

budgets, education, or time. The manager had to learn by trial and error.

The project that failed also was the manager’s first project in the field of

sustainability. The manager learned from this project and acted as a broker

of information and knowledge in the three projects that were successful.

Conclusion

The performance of a leadership style and the management of the addi-

tional knowledge exchange, jointly stimulate sustainable innovation in

building. A manager’s performance of an innovation leadership style is

(un)successful when it is (not) combined with knowledge management.

The research reported in this paper shows that an effective manager of

innovative sustainable building projects in the Netherlands would choose

an innovation leadership style with the view to stimulating the exchange

of sustainable building information and knowledge.

The research indicates that:

• managers of sustainable building innovation in the Netherlands have

to be leaders of both innovation and knowledge;

• managers of innovation in other countries, who lead comparable

sustainable innovative projects, would be expected to act in a similar

way; and

• managers of innovation in other countries, who lead innovative

projects in different technological fields, would be expected to assume

specific leadership styles and pay considerable attention to knowledge

management.

The research introduces a new literature-based framework to analyse

managers’ innovation leadership styles in their actual contexts. The empirical

146 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 147

findings indicate that this analytical framework would need to be extended

in order to incorporate management of knowledge. To specifically explore

and explain the knowledge factor in innovation leadership, further research

has to integrate knowledge leadership in its literature-base, research design

and empirical analysis.

References

Barczak, G. and Wilemon, D. (1989), ‘Leadership Differences in New Product

Development Teams,’ Journal of Product Innovation Management, 6:4, pp. 259–267.

Bossink, B.A.G. (2002), ‘A Dutch Public-Private Strategy for Innovation in

Sustainable Construction,’ Construction Management and Economics, 20:7,

pp. 633–642.

Bresnen, M., Edelman, L. Newell, S., Scarbrough, H. and Swan, J. (2003), Social

Practices and the Management of Knowledge in Project Environments,’ Inter-

national Journal of Project Management, 21:3, pp. 157–166.

Burpitt, W.J. and Bigoness, W.J. (1997), ‘Leadership and Innovations Among Teams:

the Impact of Empowerment,’ Small Group Research, 28:3, pp. 414–423.

Cavaleri, S.A. and Fearon, D.S. (2000), ‘Integrating Organisational Learning and

Business Praxis: a Case for Intelligent Project Management,’ The Learning

Organisation, 7:5, p. 251.

Chakrabarti, A.K. (1974), ‘The Role of Champion in Product Innovation,’ California

Management Review, 17:2, pp. 58–62.

Creswell, J.W. (2003), Research Design; Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods

Approaches, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Cunningham, J.B. (1997), ‘Case Study Principles for Different Types of Cases,’

Quality and Quantity, 31:4, pp. 401–423.

Eisenbach, R., Watson, K. and Pillai, R. (1999), ‘Transformational Leadership in

the Context of Organisational Change,’ Journal of Organisational Change, 12:2,

pp. 80–88.

Goverse, T., Hekkert, M.P., Groenewegen, P., Worrell, E. and Smits, R.E.H.M. (2001),

‘Wood Innovation in the Residential Construction Sector; Opportunities and

Constraints, ‘Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 34:1, pp. 53–74.

Grant, R.M. (1997), ‘The Knowledge-Based View of the Firm: Implications for

Management Practice,’ Long Range Planning, 30:3, pp. 450–454.

Harmsen, H., Grunert, K.G. and Declerck, F. (2000), ‘Why Did we Make that

Cheese? An Empirically Based Framework for Understanding what Drives

Innovation Activity,’ R&D Management, 30:2, pp. 151–166.

Hauschildt, J. and Kirchmann, E. (2001), ‘Teamwork for Innovation – the Troika

of Promotors,’ R&D Management, 31:1, pp. 41–49.

Howell, J.M. and Higgins, C.A. (1990), ‘Champions of Technological Innovation,’

Administrative Science Quarterly, 35:2, pp. 317–341.

Huang, J.C. and Newell, S. (2003), ‘Knowledge integration processes and dynamics

within the context of cross-functional projects,’ International Journal of Project

Management, 21:3, pp. 167–176.

Jung, D.I., Chow, C. and Wu, A. (2003), ‘The Role of Transformational Leadership

in Enhancing Organisational Innovation: Hypothesis and Some Preliminary

Findings,’ The Leadership Quarterly, 14:4-5, pp. 525–544.

Kangari, R. and Miyatake, Y. (1997), ‘Developing and Managing Innovative

Construction Technologies in Japan,’ Journal of Construction Engineering and

Management, 123:1, pp. 72–78.

Leadership for sustainable innovation 147

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 148

Kim, Y., Min, B. and Cha, J. (1999), ‘The Roles of R&D Team Leaders in Korea: A

Contingent Approach,’ R&D Management, 29:2, pp. 153–166.

Krause, D.E. (2004), ‘Influence-Based Leadership as a Determinant of the Inclination

to Innovate and of Innovation-Related Behaviours; An Empirical Investigation,’

The Leadership Quarterly, 15:1, pp. 79–102.

Liebowitz, J. and Megbolugbe, I. (2003), ‘A Set of Frameworks to Aid the Project

Manager in Conceptualizing and Implementing Knowledge Management

Systems,’ International Journal of Project Management, 21:3, pp. 189–198.

Lloréns Montes, F.J., Ruiz Moreno, A. and García Morales, V. (2005), ‘Influence of

Support Leadership and Teamwork Cohesion on Organisational Learning,

Innovation and Performance: An Empirical Examination,’ Technovation, 25:10,

pp. 1159–1172.

Lloyd, B. (1996), ‘Knowledge Management: The Key to Long-Term Organisational

Success,’ Long Range Planning, 29:4, pp. 576–580.

Markham, S.K. (1998), ‘A Longitudinal Examination of How Champions Influence

Others to Support Their Projects,’ Journal of Product Innovation Management,

15:6, pp. 490–504.

McDonough, E.F. and Leifer, R.P. (1986), ‘Effective Control of New Product

Projects: The Interaction of Organisation Culture and Project Leadership,’

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 3:3, pp. 149–157.

McDonough, E.F. and Barczak, G. (1991), ‘Speeding up New Product Development:

The Effects of Leadership Style and Source of Technology,’ Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 8:3, pp. 203–211.

Nadler, D.A. and Tushman, M.L. (1990), ‘Beyond the Charismatic Leader:

Leadership and Organisational Change,’ California Management Review, 32:2,

pp. 77–97.

Nam, C.H. and Tatum, C.B. (1992), ‘Strategies for Technology Push: Lessons from

Construction Innovations,’ Journal of Construction Engineering and Management,

118:3, pp. 507–524.

Nam, C.H. and Tatum, C.B. (1997), ‘Leaders and Champions for Construction

Innovation,’ Construction Management and Economics, 15:4, pp. 259–270.

Nonaka, I., Kenney, M. (1991), ‘Towards a New Theory of Innovation

Management: A Case Study Comparing Canon Inc. and Apple Computer Inc,’

International Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 8, pp. 67–83.

Norrgren F. and Schaller, J. (1999), ‘Leadership Style: Its Impact on Cross-

Functional Product Development,’ Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16:4,

pp. 377–384.

Rice, M.P., O’Connor, G.C., Peters, L.S. and Morone, J.G. (1998), ‘Managing

Discontinuous Innovation,’ Research-Technology Management, 41:3, pp. 52–58.

Roberts, E.B. and Fusfeld, A.R. (1981), ‘Staffing the Innovative Technology-Based

Organisation,’ Sloan Management Review, 22:3, pp. 19–34.

Saleh, S.D. and Wang, C.K. (1993), ‘The Management of Innovation: Strategy,

Structure, and Organisational Climate,’ IEEE Transactions on Engineering Man-

agement, 40:1, pp. 14–21.

Seaden, G. and Manseau, A. (2001), ‘Public Policy and Construction Innovation,’

Building Research & Information, 29:3, pp. 182–196.

Stoker, J.I., Looise, J.C., Fisscher, O.A.M. and De Jong, R.D. (2001), ‘Leadership and

Innovation: Relations Between Leadership, Individual Characteristics and the

Functioning of R&D Teams,’ International Journal of Human Resource Manage-

ment, 12:7, pp. 1141–1151.

148 Bart Bossink

TMSD-6_2-04-Bossink.qxp 9/11/07 3:15 PM Page 149

Toole, T.M. (1998), ‘Uncertainty and Home Builders’ adoption of technological

innovations,’ Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 124:4,

pp. 323–332.

Veshosky, D. (1998), ‘Managing Innovation Information in Engineering and

Construction Firms,’ Journal of Management in Engineering, 14:1, pp. 58–66.

Viitala, R. (2004), ‘Towards Knowledge Leadership,’ Leadership & Organisation

Development Journal, 25:5-6, pp. 528–544.

Waters, J. (2000), ‘Achieving Innovation or the Holy Grail: Managing Knowledge

or Managing Commitment?’ International Journal of Technology Management,

20:5–8, pp. 819–838.

Yin, R.K. (2004), Case Study Research; Design and Methods, Thousand Oaks: Sage,

3rd edition.

Suggested citation

Bossink, B. (2007), ‘Leadership for sustainable innovation’, International Journal of

Technology Management and Sustainable Development 6: 2, pp. 135–149, doi:

10.1386/ijtm.6.2.135/1

Contributor details

Bart A.G. Bossink is Associate Professor of Economics at VU University Amsterdam.

Contact: Bart A.G. Bossink, VU University Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics

and Business Administration, Department of Management and Organisation,

De Boelelaan 1105, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

E-mail: bbossink@feweb.vu.nl

Leadership for sustainable innovation 149

You might also like

- Winter 2007Document124 pagesWinter 2007genzimeNo ratings yet

- Topic 3 Entrepreneurial CapitalDocument17 pagesTopic 3 Entrepreneurial Capitalanon_820466543No ratings yet

- Organisational Behaviour: Teams & GroupsDocument21 pagesOrganisational Behaviour: Teams & GroupsGautam DuaNo ratings yet

- Emily Tuuk (2012) - Transformational Leadership in The Coming Decade - A Response To TDocument8 pagesEmily Tuuk (2012) - Transformational Leadership in The Coming Decade - A Response To TsugerenciasleonelsedNo ratings yet

- Technological Collaboration: Bridging The Innovation Gap Between Small and Large FirmsDocument26 pagesTechnological Collaboration: Bridging The Innovation Gap Between Small and Large FirmsHamza Faisal MoshrifNo ratings yet

- April 19, 2013 Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute: Posted On byDocument35 pagesApril 19, 2013 Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute: Posted On bysilentreaderNo ratings yet

- Meaning Making in Communications Procceses. The Rol of A Human Agency - ARTICULO-2015Document4 pagesMeaning Making in Communications Procceses. The Rol of A Human Agency - ARTICULO-2015Gregory VeintimillaNo ratings yet

- Article Review: The End of Leadership: Exemplary Leadership Is Impossible Without The Full Inclusion, Initiatives, and Cooperation of FollowersDocument1 pageArticle Review: The End of Leadership: Exemplary Leadership Is Impossible Without The Full Inclusion, Initiatives, and Cooperation of FollowersTerry Kinder100% (1)

- Goldman - Thinking About Strategy Absent The EnemyDocument47 pagesGoldman - Thinking About Strategy Absent The EnemyDharma GazNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Innovation in Science-Based Firms: The Need For An Ecosystem PerspectiveDocument35 pagesEntrepreneurial Innovation in Science-Based Firms: The Need For An Ecosystem PerspectiveRaza AliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 LeadershipDocument87 pagesChapter 1 LeadershipHandikaNo ratings yet

- Whatever Happened To KnowledgeDocument8 pagesWhatever Happened To KnowledgeLaura GonzalezNo ratings yet

- EPS2010205ORG9789058922427Document225 pagesEPS2010205ORG9789058922427Youssef KouNo ratings yet

- Network Dynamics and Field Evolution: The Growth of Interorganizational Collaboration in The Life SciencesDocument74 pagesNetwork Dynamics and Field Evolution: The Growth of Interorganizational Collaboration in The Life SciencesChintaan PatelNo ratings yet

- Charles Creegan - Wittgenstein and KierkegaardDocument106 pagesCharles Creegan - Wittgenstein and KierkegaardWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Microfluidics 2ndDocument479 pagesIntroduction To Microfluidics 2ndEragon0101 TheDragonRiderNo ratings yet

- Building Competitive Advantage Innovation and Corporate Governance in European ConstructionDocument20 pagesBuilding Competitive Advantage Innovation and Corporate Governance in European Constructionapi-3851548100% (1)

- Why Don't Teams Work Like They're Supposed ToDocument8 pagesWhy Don't Teams Work Like They're Supposed ToDS0209No ratings yet

- Strategic Monitoring SystemDocument12 pagesStrategic Monitoring SystemAnita SharmaNo ratings yet

- Main Functions of Attention: Signal Present Absent Present AbsentDocument7 pagesMain Functions of Attention: Signal Present Absent Present AbsentArcanus LorreynNo ratings yet

- Final 7-s Model PresentationDocument25 pagesFinal 7-s Model PresentationAnant KumarNo ratings yet

- Complete Project Gutenberg Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Works by Holmes, Oliver Wendell, 1809-1894Document1,994 pagesComplete Project Gutenberg Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Works by Holmes, Oliver Wendell, 1809-1894Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Power of A Vision by Ugwak O Crosky: Key Chapter: Proverbs 29:18Document7 pagesThe Power of A Vision by Ugwak O Crosky: Key Chapter: Proverbs 29:18ugwakNo ratings yet

- Dynamizing Innovation Systems Through Induced Innovation Networks: A Conceptual Framework and The Case of The Oil Industry in BrazilDocument4 pagesDynamizing Innovation Systems Through Induced Innovation Networks: A Conceptual Framework and The Case of The Oil Industry in Brazilhendry wardiNo ratings yet

- E-Business Models & MarketsDocument53 pagesE-Business Models & Marketsanmol guleriaNo ratings yet

- Optimizing Innovation with Lean and Digital ProcessesDocument10 pagesOptimizing Innovation with Lean and Digital ProcessesFrancis ParedesNo ratings yet

- Maslow-The Superior PersonDocument4 pagesMaslow-The Superior PersonAlfredo Matus IsradeNo ratings yet

- Time Conception and Cognitive LinguisticsDocument31 pagesTime Conception and Cognitive LinguisticsRobert TsuiNo ratings yet

- Ten C's Leadership Practices Impacting Employee Engagement A Study of Hotel and Tourism IndustryDocument17 pagesTen C's Leadership Practices Impacting Employee Engagement A Study of Hotel and Tourism IndustryCharmaine ShaninaNo ratings yet

- Kafka and PhenomenologyDocument19 pagesKafka and PhenomenologyAyushman ShuklaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Difference Between Perception and PerspectiveDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between Perception and Perspectivebday23100% (1)

- The Impact of Leadership and Leadership DevelopmenDocument69 pagesThe Impact of Leadership and Leadership DevelopmengedleNo ratings yet

- Coordinated Management of MeaningDocument13 pagesCoordinated Management of Meaningapi-341635018100% (1)

- Eight Dimension DescriptionsDocument2 pagesEight Dimension DescriptionsVõ Ngọc LinhNo ratings yet

- Peter Noteboom - 5 Frames of Transformational ChangeDocument38 pagesPeter Noteboom - 5 Frames of Transformational ChangeAsif Sadiqov100% (1)

- Fayol's 14 principles of management: a framework for managing organizations effectivelyDocument12 pagesFayol's 14 principles of management: a framework for managing organizations effectivelyGuillermo GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Winter 2008Document128 pagesWinter 2008bhardin4411No ratings yet

- Antonakis (2006) - Leadership What Is It PDFDocument17 pagesAntonakis (2006) - Leadership What Is It PDFRonald Wuilliams Martínez MuñozNo ratings yet

- King James Bible 5'X7'Document2,706 pagesKing James Bible 5'X7'Thomas Savage100% (1)

- Personality Dynamics - An Integrrative Approach To AdjustmentDocument456 pagesPersonality Dynamics - An Integrrative Approach To AdjustmentnesumaNo ratings yet

- Empathy - in A Tricky WorldDocument16 pagesEmpathy - in A Tricky WorldUsman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Protean and Boundaryless Careers As MetaphorsDocument16 pagesProtean and Boundaryless Careers As MetaphorsNely PerezNo ratings yet

- Morgeson Humphrey 2006 The Work Design Questionnaire WDQDocument19 pagesMorgeson Humphrey 2006 The Work Design Questionnaire WDQDaniel RileyNo ratings yet

- (Religion Cognition and Culture.) Talmont-Kaminski, Konrad-Religion As Magical Ideology - How The Supernatural Reflects Rationality-Acumen Publishing LTD (2013)Document173 pages(Religion Cognition and Culture.) Talmont-Kaminski, Konrad-Religion As Magical Ideology - How The Supernatural Reflects Rationality-Acumen Publishing LTD (2013)Anonymous QINdkjMxxoNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook On Innovation - Kapitel 3Document31 pagesThe Oxford Handbook On Innovation - Kapitel 3Thomas Dyrmann WinkelNo ratings yet

- ORDocument90 pagesORfaisalNo ratings yet

- Applied Ideation& Design Thinking PDFDocument19 pagesApplied Ideation& Design Thinking PDFAriantiAyuPuspitaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2-Reflecting On ReflectionDocument53 pagesLesson 2-Reflecting On Reflectionjudobob100% (1)

- (Robert Lo Flood) Rethinking The Fifth Discipline (Zlibraryexau2g3p.onion)Document231 pages(Robert Lo Flood) Rethinking The Fifth Discipline (Zlibraryexau2g3p.onion)Ninh LeNo ratings yet

- Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp (2005)Document11 pagesAhearne, Mathieu, & Rapp (2005)Ria Anggraeni100% (1)

- The Semiotics of BrandDocument21 pagesThe Semiotics of BrandBrad Weiss100% (1)

- Presentation On Inflation: Presented By: Darwin Balabbo ManaguelodDocument13 pagesPresentation On Inflation: Presented By: Darwin Balabbo ManaguelodJulius MacaballugNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Innovation Leadership: Hazaz Abdullah Alsolami, Kenny Teoh Guan Cheng, Abdulaziz Awad M. Ibn TwalhDocument8 pagesRevisiting Innovation Leadership: Hazaz Abdullah Alsolami, Kenny Teoh Guan Cheng, Abdulaziz Awad M. Ibn TwalhOana MariaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Innovation Leadership Styles: A Manager's in Uence On Ecological Innovation in Construction ProjectsDocument19 pagesEffectiveness of Innovation Leadership Styles: A Manager's in Uence On Ecological Innovation in Construction Projectsmy_scribd_2011No ratings yet

- Zenab y NaaranojaDocument9 pagesZenab y NaaranojaLuis Elias Baena SealesNo ratings yet

- Doing Complexity Leadership Theory How Agile Coaches at Spotify Practise Enabling LeadershipDocument19 pagesDoing Complexity Leadership Theory How Agile Coaches at Spotify Practise Enabling LeadershipLuisNo ratings yet

- Arif Kamisan Transactional Transformational LeadershipDocument10 pagesArif Kamisan Transactional Transformational LeadershipbiofatulNo ratings yet

- Ent LeadershipDocument38 pagesEnt LeadershipSofía AparisiNo ratings yet

- Hailey College of Commerce, University of The Punjab, LahoreDocument21 pagesHailey College of Commerce, University of The Punjab, LahoreAtif JanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Innovative Work Behavior of EmployeesDocument4 pagesFactors Affecting Innovative Work Behavior of EmployeesIvy EscarlanNo ratings yet

- Carmeli, A., Gelbard, R., & Gefen, D. (2010) - The Importance of Innovation Leadership in Cultivating Strategic Fit and Enhancing Firm PerformanceDocument11 pagesCarmeli, A., Gelbard, R., & Gefen, D. (2010) - The Importance of Innovation Leadership in Cultivating Strategic Fit and Enhancing Firm PerformanceMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- An Exploration of The Boundaries of Community in Community Ren - 2018 - EnergyDocument12 pagesAn Exploration of The Boundaries of Community in Community Ren - 2018 - EnergyMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Borins, S. (2002) - Leadership and Innovation in The Public SectorDocument13 pagesBorins, S. (2002) - Leadership and Innovation in The Public SectorMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Benson, A. J., Hardy, J., & Eys, M. (2015) - Contextualizing Leaders Interpretations of Proactive FollowershipDocument18 pagesBenson, A. J., Hardy, J., & Eys, M. (2015) - Contextualizing Leaders Interpretations of Proactive FollowershipMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Bel (2010) - Leadership and InnovationDocument14 pagesBel (2010) - Leadership and InnovationMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Baron Et Al (2018) - Mindfulness and Leadership FlexibilityDocument13 pagesBaron Et Al (2018) - Mindfulness and Leadership FlexibilityMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Policymaking A CritiqueDocument16 pagesEvidence Based Policymaking A CritiqueMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Universe Definition DictionaryDocument11 pagesUniverse Definition DictionaryKristanae ReginioNo ratings yet

- Kerusakan Hutan Rawa Gambut Di Semanjung Kampar: Studi Tentang Mncs Dan NegaraDocument6 pagesKerusakan Hutan Rawa Gambut Di Semanjung Kampar: Studi Tentang Mncs Dan NegaraRivaldi DharmawanNo ratings yet

- Blue Transformation A Vision For Faos Work On Aquatic Food SystemsDocument40 pagesBlue Transformation A Vision For Faos Work On Aquatic Food SystemsMariana CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- Simulacro Icfes LecturasDocument6 pagesSimulacro Icfes LecturasCarmen Andrea Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- New Guidance On Product Family Adoption For Radiation Sterilization: AAMI TIR 35:2016Document39 pagesNew Guidance On Product Family Adoption For Radiation Sterilization: AAMI TIR 35:2016RakeshNo ratings yet

- The Greens Junction, Jebel Ali Race Course RD Dubai, Dubai 22072 United Arab EmiratesDocument1 pageThe Greens Junction, Jebel Ali Race Course RD Dubai, Dubai 22072 United Arab EmiratesPearce BridgesNo ratings yet

- 1-Intro To Design Thinking 2021-2022 For GclassroomDocument106 pages1-Intro To Design Thinking 2021-2022 For Gclassroom11No ratings yet

- Unit 7 - Test 1 - Anh 8Document3 pagesUnit 7 - Test 1 - Anh 8Bảo LongNo ratings yet

- National Guiddelines Ministry of Aqriculture SSIGL-16-Canals-Related-structures-Ver-6Document142 pagesNational Guiddelines Ministry of Aqriculture SSIGL-16-Canals-Related-structures-Ver-6ZELALEMNo ratings yet

- Smart Way of ConstructionDocument64 pagesSmart Way of ConstructionSri Rama ChandNo ratings yet

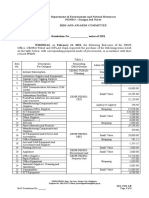

- BAC Resolution No. - Series of 2021Document3 pagesBAC Resolution No. - Series of 2021R13 PENRO Surigao Del NorteNo ratings yet

- Design & Conduct of TrainingDocument26 pagesDesign & Conduct of TrainingParas PathelaNo ratings yet

- TQM 3Document7 pagesTQM 3AllenNo ratings yet

- Social Compliance Audit UIIDP2021Document26 pagesSocial Compliance Audit UIIDP2021Amin FentawNo ratings yet

- WEEKLY TEST in SCIENCE 5 q4Document13 pagesWEEKLY TEST in SCIENCE 5 q4mary annNo ratings yet

- Creating A Positive School CultureDocument7 pagesCreating A Positive School CultureRogen AlintajanNo ratings yet

- Demo Lecture EnvDocument19 pagesDemo Lecture Envtahseen khanNo ratings yet

- CORR Penyelaras DEJ40033 Sesi 1 20212022 - SignedDocument3 pagesCORR Penyelaras DEJ40033 Sesi 1 20212022 - Signedarechor1605No ratings yet

- 10E, 10H: Week 36 Ôn Tập Khảo Sát PronunciationDocument9 pages10E, 10H: Week 36 Ôn Tập Khảo Sát PronunciationHàNhậtNguyễnNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola Amatil & Dynapack - Indonesia PDFDocument2 pagesCoca-Cola Amatil & Dynapack - Indonesia PDFShouvik MukhopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Green City - GuidelinesDocument51 pagesGreen City - GuidelinesAli Wijaya100% (1)

- SwotDocument18 pagesSwotapi-529669983No ratings yet

- Factsheet - International CommunicationsDocument4 pagesFactsheet - International CommunicationsMichael SiaNo ratings yet

- Socio Cultural Basis of Design in CommunitiesDocument44 pagesSocio Cultural Basis of Design in CommunitiesUniqueQuiverNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary test covers environmental termsDocument1 pageVocabulary test covers environmental termsPatrycjaxddNo ratings yet

- Its a Craft! Boosting Creativity through RecyclingDocument4 pagesIts a Craft! Boosting Creativity through RecyclingCristine BellenNo ratings yet

- Ambler Boiler HouseDocument13 pagesAmbler Boiler HouseOmer MirzaNo ratings yet

- Columbus Climate Action PlanDocument102 pagesColumbus Climate Action PlanWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Button MuhsroomDocument5 pagesButton MuhsroomAS & AssociatesNo ratings yet

- Basic Waste Management PlanDocument8 pagesBasic Waste Management Plancraig beatsonNo ratings yet