Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Self Talk

Self Talk

Uploaded by

Dilla Nurdiani0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views6 pagesOriginal Title

Self-Talk

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views6 pagesSelf Talk

Self Talk

Uploaded by

Dilla NurdianiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Children’s Self-Talk and

Academic Self-Concepts

The impact of teachers’ statements

Paul C.

Summary

Data were collected from 269 Australian primary

school children in grades 3 to 7. Self-report

questionnaires measuring students? perceptions of the

frequency of positive and negative statements directed

to them by their teacher, their positive and negative self-

talk; and their reading, mathematics and learning

self-concepts were administered. Positive statements

made by teachers were found to be directly related to

positive self-talk and to maths and learning self-

concepts. Teachers’ positive statements were also

indirectly related to reading self-concept through

positive self-talk. Negative statements made by teachers

were not predictive of self-talk or self-concepts for the

total sample but were predictive of maths self-concept

for girls and negative self-talk for boys. Implications for

teachers and educational psychologists are discussed.

Introduction

Influence of teachers’ feedback on

children’s self-talk and self-concepts

There are two models that describe how teachers?

feedback impacts on students’ self-concept. The first,

Craven, Marsh and Debus (1991), is a model which

describes the influence of teachers’ statements on

children’s self-concepts. This model was developed

within the context of direct approaches to enhancing

children’s self-concepts in academic areas. Craven et

al describe an internal mediating process model

whereby (A) a student is given specific performance

feedback by the teacher (you did well on that maths

task, you have good ability in maths: Positive teacher

statements); (B) the student internalises the statement

(I did well on that; Iam good at maths tasks; well

done: Positive self-talk); and (C) the student then

Educational Psychology In Practice Vol 15, No 3, October 1999

Burnett

sgeneralises the self-talk to form or modify their maths

self-concept which is comprised of an evaluative/

competency/cognitive component (I am good at

maths and I do well at maths) and a descriptive!

affective component (I like maths and I enjoy maths).

Burnett (1994b; 1996b) describes these two

components of self-concept.

The second model was described more recently by

Blote (1995). He outlines a model based on research

reported by Babad (1990); Blumenfeld et al (1982);

Brattesani et al (1984); Cooper and Good (1983);

Parsons et al (198: ind Weinstein et al (1987). On

the basis of synthesising the findings of these studies,

Blote describes the following model. A teacher's

expectations (A) influences his or her behaviour which

is reflected in how feedback is presented to students

(B). The teacher’s behaviour and accompanying

feedback is then perceived, interpreted, and integrated

by the student [Self-Talk] (C), who as a result of this

internalisation confirms or changes his or her self-

expectations [Self-Concepts] (D) in line with the

direction of the teacher's expectations.

The findings of the following studies are

specifically relevant to the current study which

focuses on the BCD section of Blote’s (1995) model.

These studies noted by Blote found that:

+ ahigh frequency of positive academic feedback

was associated with a high self-concept of abil-

ity (Blumenfeld et al, 1982)

* for boys, teachers’ praise was found to be asso-

ciated with a high self-concept of maths ability

(Parsons et al, 1982)

* classrooms with high rates of criticism by the

teacher were associated with Jower students’ ef-

ficacy beliefs, while classrooms with high

teacher-initiated interaction had students with

higher efficacy beliefs (Cooper and Good, 1983).

195

Steps ABC of the Craven et al (1991) model are

similar to the BCD steps of the more general Blote

(1995) model. Craven et al (1991) point out that the

specific process as to how feedback affects self-

concepts has not been investigated but instead

researchers and teachers have assumed that teacher

feedback and praise leads to positive outcomes for all

children.

Relationships between non-targeted

feedback and general self-perceptions

Research studies have investigated the relationships

between statements made by significant others and

general self-perceptions (Blake and Slate, 1993;

Burnett and McCrindle, in press; Campbell, 1989;

Elgin, 1980; Goodman and Ritini, 1991; Joubert,

1991). The results of these investigations indicate that

positive interactions and positive statements made by

significant others are related to positive self

perceptions, while negative interactions and

statements ‘are associated with negative self-

perceptions, Additionally, positive statements made

by significant adults (parents and teachers) are found

to be related to children’s positive self-talk (Burnett,

1996a). Further, a number of studies (Burnett, 199433

Burnett and McCrindle, in press; Kent and Gibbons,

1987; Lamke et al, 1988; Philpot et al, 1995) report

associations between self-talk and self-perceptions,

particularly global self-esteem. Collectively, the results

of these studies provide a substantive body of

knowledge which suggests that children’s self-talk

may play a mediating role between teachers’ positive

statements (praise) and their negative statements

(correction or punishment) and children’s self-

perceptions. This study seeks to address this issue,

noting implications for teachers.

Teachers’ statements and self-talk

Little research has been conducted which specifically

investigates the relationship between statements made

by teachers and self-talk. In one of the few studies

conducted in this area, Burnett (1996a) found that

the perceived frequency of non-targeted positive

statements made by teachers was the most significant

predictor of children’s positive self-talk, being higher

than positive statements made by peers, parents and

siblings respectively. An interesting gender difference

was found in that the perceived frequency of positive

statements made by teachers was more predictive for

girls" positive self-talk than it was for boys’ positive

self-talk. Specifically, when the analysis was

196

undertaken separately for girls and boys, positive

teacher statements were the best predictor of girls?

itive self-talk, while for boys it rates fourth behind

positive and negative statements made by parents and

positive statements made by peers.

OF note in this study was the finding that the

perceived frequency of negative statements made by

teachers was not found to be predictive of either

positive or negative self-talk in children. This finding

was replicated by Burnett and McCrindle (in press)

and highlights the significant influence of teachers’

positive statements when compared with negative

statements.

Aim of this study

Blote (1995, p 225) states that ‘further research is

still needed on the variables mediating between

teacher expectancy and student self-concept’.

Accordingly, this study investigated the relationships

between children’s perceptions of the frequency of

positive and negative statements made by teachers

and their self-talk and academic self-concepts

(reading, mathematics and learning). Gender

differences were also investigated given the previous

difference findings reported by Burnett (1996b) and

Parsons et al (1982).

Method

Participants

‘A sample of 269 children in grades 3 to 7 (aged from

8 years to 13 years) at a middle-class, metropolitan

elementary school agreed to participate in the scudy.

There were 144 boys and 125 girls involved in the

study with a mean age of 9 years and 8 months.

Instrumentation

Significant Others Statements Inventory (SOSI):

Burnett (1996a) outlined the development of the

SOSI, which has eight sub-scales measuring children’s

perceived frequency of positive and’ negative

statements made by parents, teachers, siblings and

peers. In this study only the teachers’ scales were

administered. The reliability coefficients for the two

scales for the sample used for this study were

Teachers’ Negative Statements 0.70 (three items) and

Teachers’ Positive Statements 0.81 (five items).

Self-Talk Inventory (STI): Burnett (1996a) described

the development process for the STI which resulted

in the emergence of two scales: a positive self-talk

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol 15, No 3, October 1999

scale (eg, Just stay calm, Everything will be OK, Ie'll

work out, I'll do well) and a negative self-talk scale

(eg, Everyone will think I'm hopeless, This is going

to be awful, I'm going to muck this up, I'm hopeless).

The reliability coefficients for the 17-item Positive

Self-Talk Scale (PSTS) and the 16-item Negative Self-

Talk Scale (NSTS) were 0.89 and 0.86 respectively.

Self-Concepts: The self-concept scales used in this

study were the reading and maths self-concept scales

developed and used by Burnett (1994b; 1996b). High

reliabilities (Reading Self-Concept 0.87 and

Mathematics Self-Con

cept 0.84) were reported by Burnett (1994b). As a part

of this study a Learner Self-Concept scale was

developed and administered. This four-item scale was

found to have an internal consistency coefficient of

0.82.

Procedures

An experienced research assistant administered the

instruments described above in class time. If children

experienced any problems with reading an item they

were assisted.

Data analysis and results

A model-testing procedure was used to test the

relationships between the three groups of variables.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used and

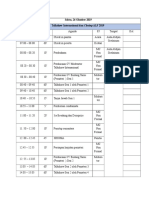

Figure 1. Model for the total sample

Teacher Statements Self-Talk

©)

2 @)

SEM results: GF1=0.95, AGFI=0.91, TLI=0.95, RNI=0.

Gy

-

the data were analysed using LISREL 7.0 within

SPSS. SEM can be used to test the fit of the data to

an hypothesised model. Modifications to the model

can then be made to produce a model of best fit.

These procedures were used to produce three

diagrammatic representations of the relationships

between teachers’ statements and children’s self-talks

and self-concepts in general, and for boys and gicls

separately. The results for all three models suggested

a good fit between the data and the final models

produced. The three models and their results are

shown in Figures 1 to 3.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the

mediating effect of self-talk between positive and

negative statements made by teachers and their

students’ academic self-concepts (reading,

mathematics and learning). The results for the toral

sample indicate that positive self-talk does mediate

between the perceived frequency of teachers’ praise

and students’ reading self-concept. This provides

support for the internal mediating model forwarded

by Craven et al (1991), Additionally, negative self-

talk was found to be predictive of maths self-concept

bur negative self-talk was not related to teacher

statements, and this was needed to support the

mediating model. Furthermore, the results indicate

that positive statements made by teachers were more

Academic Self-Concepts

&

.98, RMSR=0.045, ChiS

The percentages of variance accounted for by the other variables are presented.

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol 15, No 3, October 1999

197

Figure 2. Model for the boys’ sample

Self-Talk

Teacher Statements

Academic Self-Concepts

SEM results: GFI=0.91, AGFI=(

The percentages of variance accounted for by the other

influential than negative statements as shown first, by

direct paths from positive statements to positive self-

talk and maths and learning self-concepts and,

second, by the fact that negative statements were not

predictive of any of the self-talk or self-concept

variables.

Some gender differences were noted when the

modified model from the total sample was tested

separately for boys and girls. The most significant

finding from the separate analyses is the emergence

of significant paths from negative statements made by

teachers. For boys, teachers’ negative statements were

related to negative self-talk which in turn was

predictive of maths self-concept. This supports the

internal mediating model. For girls, teachers’ negative

statements had a direct effect on maths self-concept.

Implications for teachers and educational

psychologists

The most powerful outcome for teachers and for

educational psychologists (EPs) wishing to draw

upon this study is the ‘power of the positive’.

Children’s perceptions of the frequency of positive

statements made by teachers, which included general

praise and feedback, was directly related to their

beliefs about themselves as mathematicians and

learners. Children who perceived that their teachers

said positive things to them had higher maths and

learner self-concepts, whereas children who perceived

198

.86, TLI=0.94, RNI=0.96, RMSR=0.06, ChiS

1 variables are presented.

that their teachers did not say many positive things

to them had lower maths and learner self-concepts.

Additionally, children who perceived that their

teachers said positive things to them had higher

positive self-talk and higher reading self-concept

while children who reported that their teacher did

not say many positive things to them had lower

positive self-talk and lower reading self-concept. This

indicates the impact of the presence or absence of

positive statements in the classroom.

There were, however, some gender differences in

students’ perception of the negative statements made

by teachers. Negative statements were related to

boys’ negative self-talk and maths self-concept. This

suggests that the boys who perceived that their

teachers spoke negatively to them had high negative

self-talk and low maths self-concept. However,

who perceived that their teachers spoke negativ

them did not have low negative self-talk but di

low maths self-concept.

Ir should be noted that teacher expectations for

their children and the children’s academic

achievement were not measured in this study. Future

research could measure these in an endeavour to

evaluate the circular nature of the model, which is

(A) A teacher’s expectations of a child in’a specific

subject area affects (B) the delivery of feedback and

praise in that area which is (C) internalised as self-

talk by the child and influences the (D) child’s

self-concept in that specific area which in turn affects

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol 15, No 3, October 1999

Figure 3. Model for the girls’ sample

Teacher Statements Self-Talk

Gs

@)

(7

Academic Self-Concepts

Va

Lo

93, AGFI=0.89, TLI=0.99, RNI=0.99, RMSR=0.07, ChiSQ=68; df=66.

The percentages of variance accounted for by the other variables are presented.

(E) the child’s achievement in that area which then

reinforces (A) the teacher's original expectation.

In the meantime, EPs are in a key position to

investigate this model through their practice. More

immediately, this study along with other work cited,

provides the evidence base for EPs wishing to frame

recommendations to the teaching and non-teaching

staff of a school about the potential value added to

learning through the relatively low-cost expedient of

directly communicating positive expectation to

children.

Acknowledgement

The support and assistance of Ms Andrea McCrindle,

Senior Research Assistant, Centre for Cognitive Processes

in Learning, Queensland University of Technology, is

gratefully acknowledged.

References

Babad, E. (1990) ‘Measuring and changing teachers’

differential behavior as perceived by students and

teachers’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 683~

690,

Bagozzi, R.P and Heatherton, T.F. (1994) ‘A general

approach to representing multifaceted personality

constructs: application to self-esteem’, Structural

Equation Modeling, 1, 35-67.

Blake, P.C. and Slate, J.R. (1993) ‘A preliminary

investigation into the relationship between adolescent

self-esteem and parental verbal interaction’, The School

Counselor, 41, 81-85.

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol 15, No 3, October 1999,

Blote, A.W. (1995) ‘Students’ self-concept in relation to

perceived differential teacher treatment’, Learning and

Instruction, §, 221-236.

Blumenfeld, P.C., Pintrich, P-R., Meece, J. and Wessels, K.

(1982) ‘The formation and role of self-perception of

ability in elementary classrooms’, Elementary Schoo!

Journal, 82, 401-420.

Brattesani, K.A., Weinstein, R.S. and Marshall, H.H.

(1984) ‘Student perceptions of differential teacher

treatment as moderators of teacher expectation effects’,

Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 236-247.

Burnett, PC. (1994a) ‘Self-talk in upper elementary schoo!

children: its relationship with irrational beliefs, self-

esteem, and depression’, Journal of Rational-Emotive &

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 12, 181-188.

Burnett, P.C. (1994b) ‘Self-concept and self-esteem in

elementary school children’, Psychology in the Schools,

31, 164-171.

Burnett, P.C. (1996a) ‘Children’s self-talk and significant

others’ positive and negative statements’, Educational

Psychology, 16, 57-67.

Burnett, P.C. (1996b) ‘Gender and grade differences in

elementary school children’s descriptive and evaluative

self-statements and self-esteem’, School Psychology

International, 17, 159-170.

Burnett, PC. (1998) ‘Measuring behavioral indicators of

self-esteem in the classroom’, Journal of Humanistic

Education and Development, 37, 107-116.

Burnett, RC. and McCrindle, A.R. (1999) ‘The relationship

between significant others’ positive and negative

statements and self-talk, self-concepts and self-esteem’,

Child Study Journal, 29, 39-48,

199

Campbell, B. (1989) ‘When words hurt: beware of the

dangers of verbal abuse’, Essence, 20, 86.

Cooper, H.M. and Good, TL. (1983) Pygmalion Grows

up: Studies in the Expectation Communication Process.

New York: Longman,

Craven, R.G., Marsh, H.W. and Debus, R.L. (1991)

“Effects of internally focussed feedback and attributional

feedback on enhancement of academic self-concept’,

Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 17-27.

Elgin, S. (1980) The Gentle Art of Verbal Self-Defense.

Boston, MA: Prentice Hall.

Goodman, S. and Ritini, J. (1991) ‘Depressed mothers’

expressed emotion and their children’s self-esteem and

mood disorders’, Paper presented at the Biennial

Meeting of the Society for Research in Child

Development, Seattle, WA, April 18-21.

Joubert, C.E. (1991) ‘Self-esteem and social desirability in

relation to college students’ retrospective perceptions of

parental fairness and disciplinary practices’,

Psychological Reports, 69, 115-120.

Kent, G. and Gibbons, R. (1987) ‘Self-efficacy and the

control of anxious conditions’, Journal of Behavior

Therapy and Experimental Psychology, 1, 33-40.

Lamke, LK, Lujan, BM. and Showalter, J.M. (1988) ‘The

case for modifying adolescents’ cognitive self-

statements’, Adolescence, 23, 967-974.

200

Marsh, H.W. (1991) ‘Multidimensional students’

evaluations of teaching effectiveness: A test of alternative

higher-order structures’, Journal of Educational

Psychology, 62, 17-34.

Parsons, J.E., Kaczala, C. and Meece, J. (1982)

‘Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs:

Classroom influences’, Child Development, 53, 322-339.

Philpot, V.D., Holliman, W.B. and Madonna, S. (1995)

‘Self-statements, locus of control, and depression in

predicting self-esteem’, Psychological Reports, 76, 1007—

1010.

Reynolds, A.J. and Walberg, H.J. (1991) ‘A structural

model of science achievement’, Journal of Educational

Psychology, 83, 97-100.

Weinstein, RS., Marshall, KUHL, Sharp, L. and Botkin, M.

(1987) ‘Pygmalion and the student: age and classroom

differences in children’s awareness of teacher

expectations’, Child Development, 58, 1079-1093.

Paul C. Burnett is a Professor and Head of School

of Teacher Education at Charles Sturt University,

Bathurst, New South Wales 2795S, Australia.

This article was submitted in September 1998 and

accepted after revision in February 1999.

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol 18, No 3, October 1999

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- LatihanDocument2 pagesLatihanDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS Bahasa Jepang Kelas XDocument3 pagesSoal PTS Bahasa Jepang Kelas XDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet

- Pas Jepang XiDocument3 pagesPas Jepang XiDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet

- Effects of Self-Talk On Academic Engagement and Academic RespondingDocument17 pagesEffects of Self-Talk On Academic Engagement and Academic RespondingDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet

- Rundown Talk ShowDocument2 pagesRundown Talk ShowDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet

- Qualitative ResearchDocument25 pagesQualitative ResearchDilla NurdianiNo ratings yet