Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Presented By: Dr. Swarnali Biswas, PG 1 Year Department of Prosthodontics Chandra Dental College and Hospital

Uploaded by

ankita0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views52 pagesOriginal Title

ageing-converted

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views52 pagesPresented By: Dr. Swarnali Biswas, PG 1 Year Department of Prosthodontics Chandra Dental College and Hospital

Uploaded by

ankitaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 52

Presented by :

Dr. Swarnali Biswas, PG 1st year

Department of Prosthodontics

Chandra Dental College and Hospital

Introduction

Bone

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

Nerves and musculature

Oral mucosa

Taste and smell

Salivary glands

Teeth

Conclusions

Worldwide population demographics are changing rapidly and the

proportion of older people is growing faster than any other age group.

Globally, poor oral health among older people has traditionally been

manifest in high levels of tooth loss, dental caries and periodontal

disease experience, as well as xerostomia and oral precancer/cancer.

In addition, evidence of the relationship between oral health and poor

general health continues to grow with links between severe periodontal

disease and diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease and chronic

respiratory disease the focus of much research.

Age changes are manifest in the oral and dental tissues.

What is seen is a combination of physiological age changes with

superimposed pathological and iatrogenic effects.

The masticatory apparatus compromises :

1. Bone

2. Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

3. Nerves and musculature

4. Oral mucosa

5. Taste and smell

6. Salivary glands

7. Teeth

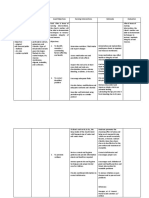

Flow chart summarising the main ageing changes induced by age in the eating process. (+), Positive tendency of the

relationship; (–), negative tendency of the relationship; (?), partially known or unknown consequences.

Increasing age is associated with

progressive reduction in bonemass

resulting in osteoporosis.

Agerelated osteoporosis is common

and, in edentulous patients, may play

a role in atrophy of alveolar and

possibly basal bone.

Atrophy of alveolar bone is related

mainly to tooth loss. Extent of alveolar bone height following loss of

lower teeth.

Its extent increases with age resulting,

in the absence of dentures, in loss of

facial height with upwards and

forwards posturing of the mandible.

Loss of alveolar bone is more extensive

and occurs more rapidly in the

mandible than in the maxilla.

Levels of the cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX

2) enzyme, which plays an essential

role in bone repair, decline

dramatically with ageing. This may Patient exhibiting loss of vertical face height due to

explain the delayed bone healing that overclosure and posturing of the mandible.

occurs in older patients.

Research is now being conducted to

stimulate activity of the COX 2 enzyme

and subsequent bone healing.6

Atrophy of a lower edentate mandible

Residual ridge resorption

Definition: The diminishing quantity

and quality of the residual ridge after

teeth are removed (GPT8).

Classification

Atwood classified the progression of

residual ridge resorption (RRR) as

follows:

• Order 1: Pre extraction

• Order 2: Post extraction

• Order 3: High, well rounded

• Order 4: Knife-edged

• Order 5: Low, well rounded

• Order 6: Depressed

Resorption pattern

Generally women show more

RRR than men.

During the first year following

extraction, reduction in

residual ridge height is 2–3 mm

in maxilla and 4–5 mm for

mandible. After this, the

process will continue but with

reduced intensity.

Mandible shows 0.1–0.2 mm

resorption annually, which is

four times more than

edentulous maxilla.

The maxillae resorb upward

and inward to become

progressively smaller because

of the direction and inclination

of the roots of the teeth and

the alveolar process. The longer

the maxillae have been

edentulous, the smaller their

bearing area is likely to be.

The opposite is true of the

mandible, which inclines

outward and becomes

progressively wider according

to its edentulous age. This Progressive resorption of the maxillary and mandibular

progressive change of the ridges makes the maxillae narrower and the mandible

edentulous mandible and wider. The lines A and B represent the centers of the

maxillae makes many patients ridges. The distance between them becomes greater as

appear prognathic. the mandible and maxillae resorb.

Aetiology

It is assumed that the degree of residual ridge reduction results from a

combination of anatomical, metabolic, and mechanical determinants.

Severe residual ridge reduction of the mandible has been related to a

small gonial angle (a marked mandibular base bend and a posterior

position of the lower incisal edges in relation to the mandibular body).

Progressive loss of bone under dentures is a manifestation of

osteoporosis.

There is a strong association between the skeletal bone density and bone

density of the mandible, and the mandible is also affected by

osteoporosis.

Low bone mineral content and osteoporotic changes predispose to a more

rapid residual ridge reduction, particularly in the maxilla.

The mechanical factors (masticatory or parafunctional forces)

transmitted by the denture or the tongue to the residual ridge are

assumed to be important factors in the remodeling process.

Consequences of residual ridge reduction

Loss of sulcus width and depth

Displacement of the muscle attachment closer to the crest of the

residual ridge

Loss of the vertical dimension of occlusion

Reduction of the lower face height

Anterior rotation of the mandible

Increase in relative prognathia

Changes in interalveolar ridge relationship

Morphological changes : sharp, spiny, uneven residual ridges and

location of the mental foramina close to the top of the residual ridge.

Reduced mechanical load due to tooth loss affects the density, stiffness, and

strength of bone structure (Giesen et al. 2003).

Remodelling may result in disc displacement, particularly anterior

displacement.

The retrodiscal tissues may show adaptive changes associated with decreased

cellularity and vascularity, and increased density of collagen, and may

eventually function as an articular disc.

In some cases the displacement may lead to perforation of the disc, particularly

of its posterior attachment, resulting in progressive joint damage.

The difference between dentate and edentulous subjects involves bone mass,

morphology, and mechanical properties of components of the masticatory

system, e.g., teeth, muscles, mandibular condyles, and the position of the

glenoid fossa (Hongo et al. 1989, Kawashima et al. 1997, Raustia et al. 1998,

Bassi et al. 1999,Giesen et al. 2003).

Te= temporal bone, Co= condyle. (A) Normal condyle of the tempomandibular

joint, (B) flattening of the articular surface of the condyle, (C) subcortical

sclerosis, (D) osteophyte, (E) microcyst, (F) marginal erosion, (G) periarticular

ossicle, (H) deformity (By permission of Peltola 1995).

Age Changes in the Mandible

The morphology of the mandibular condyle varies considerably both in size and shape

greatly among different age groups and individuals. This is due to developmental

variability as well as remodeling of condyle to accommodate malocclusion,

developmental abnormalities and diseases.

The most prevalent morphologic changes are detected in the TMJ of elderly persons

due to the onset of joint degeneration. The shape of the condyle may be

categorized into five basic types: Flattened, convex, angled, rounded, and concave.

At birth

The angle is obtuse (175°), and the condyloid portion is nearly in line with the body.

The coronoid process is of comparatively large size and projects above the level of

the condyle.

Childhood

The angle becomes less obtuse, owing to the separation of the jaws by the teeth; about

the 4th year, it is 140°.

Old age

The neck of the condyle is more or less bent backward in old ages. Disc displacement,

perforation, disc deformation, and arthrosis seem to increase with age.

Age Changes in Disc

At the age of 9-10 weeks, the articular disc has a more cellular structure with an

irregular arrangement of fibers.

At the 11th week, the disc consists of fusiform cells, which are located mainly on its

surface and densely arranged collagenous fibers.

At the 12th week, the shape of disc changes into a thinner central part and a thickened

peripheral part.

The histological study shows avascular anterior part of the disc and is composed of

woven fibrous tissue, whereas the posterior part is of looser texture and may be

subdivided into an upper zone rich in elastic tissue and a lower zone, which has

many large blood vessels.

As age advances, there is a progressive decrease in cellularity and an increase in collagen

fibers in the disc. The disc becomes thinner and shows hyalinization and chondroid

changes.

Age Changes in Synovial Fluid

Become fibrotic with thick basement membrane changes in blood vessels and nerves in

TMJ:

• Walls of blood vessels thickened

• Nerves decrease in number.

These age changes lead to:

1. Decrease in the synovial fluid

formation.

2. Impairment of motion due to

decrease in the disc and capsule

extensibility.

3. Decrease the resilience during

mastication due to chondroid changes

into collagenous elements.

4. Dysfunction in older people.

Muscle function is dependent on the performance of the nervous

system and both exhibit independent age-related changes.

Nerve cell loss is universal in old age and is exhibited in the brain and

spinal cord.

There are also age-related changes in neurotransmitters, resulting in

motor dysfunction.

Peripheral nerve function declines with age as there is a reduction

in conduction velocity, increased latencies in multi-synaptic pathways,

decreased conduction at neuromuscular junctions and loss of

receptors.

Continued muscle function is a major requirement for the maintenance of

speech and mastication.

In all patients with advancing age there is a reduction in total muscle mass

which occurs through a reduction in the number of muscle fibres rather

than a major reduction in muscle fibre size.

Electrophysiological studies have shown a loss of motor units with age,

particularly in those over the age of 60 years, which manifests as a reduction

in muscle strength and reduced masticatory forces.

Age induces a lengthening of the chewing process associated with a

reduction in muscle activity, suggesting that elderly patients adapt their

chewing behaviour to changes in chewing activity.

This affects foods such as dry bread or meat that are hard to chew (Kohyama et

al. 2002; Mioche et al. 2002b) but not foods that are easy to chew, such as

gelatine gels (Hatae et al. 2001).

Older persons also have a less

coordinated chewing stroke close to

maximum intercuspation, probably

because of a general deficit in the central

nervous system, and some individuals

who assume the characteristic stoop of

old age experience pain on swallowing

because of osteophytes and spurs

growing on the upper spine adjacent

to the pharynx.

A noticeable change in swallowing

strongly suggests that there might be an

underlying pathosis, such as

Parkinson’s disease or palsy that is not

a part of normal aging (Sonies, 1992).

The stratified squamous epithelium becomes

thinner, loses elasticity, and atrophies with

age. A declining immunological

responsiveness further increases the

susceptibility to infection and trauma.

An increased incidence of oral and systemic

disorders, along with increased use of

medications, may lead to oral mucosal disorders Chronic candidal infection

in elderly persons. Elderly patients may develop under a full upper

vesiculobullous, desquamative, ulcerative, prosthesis.

lichenoid and infectious lesions of the oral

cavity.

Denture stomatitis

It is a pathological reaction of the denture-bearing

mucosa.

It is also known as denture-induced stomatitis,

denture sore mouth,

inflammatory papillary hyperplasia or chronic atrophic candidiasis.

Classification (newton)

Type 1: Localized simple inflammation or pin-point hyperaemia.

Type 2: Erythematous or generalized simple type presenting a more diffuse

erythema involving a part or the entire denture-covered mucosa.

Type 3: Granular type (inflammatory papillary hyperplasia) commonly

involving the central part of the hard palate and the alveolar ridges. It is

often seen associated with type 1 or type 2.

Candida albicans is most often

associated with denture

stomatitis along with the other

causative factors. It is then termed

as Candida-associated denture

stomatitis.

The diagnosis of Candida-

associated denture stomatitis is

confirmed by the presence of

mycelia or pseudohyphae in a direct

smear and/or the isolation of

Candida in high numbers from the

lesion (>50 colonies).

Oral cancer

Predisposing factors

Use of heavy alcohol and tobacco, uneducated

and low socioeconomic status, which lead to poor

dental health.

Oral cancer is primarily a disease of ageing and

associated cell dysregulation.

It is estimated that more than 90% of all oral

cancers in developed countries occur in individuals

older than 50 years, with a mean onset during the

sixth decade of life.

Oral cancer is associated with high morbidity and a

particularly poor survival rate of less than 50% after

5 years.

Burning mouth syndrome

Definition

Burning pain in the tongue or other oral

mucous membrane associated with normal

signs and laboratory findings lasting at least

4–6 months (International Association for

the Study of Pain).

In this condition, the oral mucosa appears

clinically healthy.

It must be differentiated from ‘burning

mouth sensations’ where the oral mucosa is

inflamed due to mechanical denture

irritation.

Angular cheilitis

Angular cheilitis is a multifactorial disease affecting the commissure of the

lips and is commonly seen in denture wearers.

Aetiology

• Loss of vertical dimension or worn-out dentures – deep folds of skin are

produced at the corners of the mouth. The skin becomes macerated and

fissured, predisposing to infection – usually candidal or staphylococcal.

• Nutritional deficiencies such an iron deficiency, vitamin B.

• Other uncommon predisposing factors include AIDS, diabetes and

neutropenia.

Clinical examination

• Deep fissures and cracks at the corners of the mouth that may be ulcerated.

A superficial exudative crust may form.

• The fissures do not involve the mucosa on the inside of the mouth, but stop

at the mucocutaneous junction.

• Associated burning sensation or dryness at the corners.

Angular cheilitis seen at the commissure of the lips.

The scars of a lifetime are revealed dramatically on the skin as wrinkles,

puffiness, and pigmentations, but the changes are not all manifestations of

degeneration.

Fewer Langerhans’ cells in older skin can prevent undesirable

immunological responses.

Mottling of the skin protects against the sun.

The leathery look characteristic of the older sun worshipper is caused by

epidermal growths with large melanocytes—solar lentigines— that thicken

in the epidermis.

Gradually the dermis thins, enzymes dissolve collagen and elastin, and

wrinkles appear when layers of fat are lost.

Age reduces the concavity and “pout”

of the upper lip, and it flattens the

philtrum.

The nasolabial grooves deepen, which

produces a sagging look to the middle

third of the face, whereas atrophy of

the subcutaneous and buccal pads of

fat hallows the cheeks.

Subsequently, as the loss of fat

continues, support for the Appearance of the lower two thirds of an

presymphyseal pad of fat disappears, elderly person’s face demonstrating the

typical droop of the upper lip that

and the upper lip droops (cheiloptosis) accentuates the mandibular incisors

over the maxillary teeth.

These changes are accentuated even more dramatically when teeth are

missing or when there is a loss of occlusal vertical dimension.

•Sensitivity to taste declines with age,

and especially in older persons with

Alzheimer’s disease (Murphy, 1993).

•Also, the preference for specific flavors

changes over time to favor higher

concentrations of sugar and salt.

•Complaints of an impairment affecting

the sense of taste at any age should be

investigated thoroughly because they

forebode an upper respiratory infection

or a serious neurological disorder.

Possible causes of olfactory and taste disorders.

Most studies suggest that the sense of smell is more impaired by ageing

than the sense of taste.

Olfactory cells which respond to smells are renewed much more slowly in

elderly people.

Olfactory acuity declines with age as the number of olfactory nuclei in the

brain decline and the olfactory receptors in the roof of the nasal cavity

regress.

As a result, older people generally have greater difficulty differentiating

among food odours than younger people.

A diminution of taste results from the degeneration of taste buds and a

reduction in their total number as renewal is much slower in elderly

people.

Elderly people have considerable differences in their sensory perception

and capacity to detect the pleasantness of foods compared with younger

people.

This can lead to older people adding ingredients such as sugars or salt to

foodstuffs which can have adverse health effects.

Complaints of a dry mouth

(xerostomia) and diminished

salivary output are common in

older populations.

Estimates of xerostomia and

salivary hypofunction indicate that

approximately 30% of the

population 65 years and older

experience these disorders and

their accompanying oral and Oral and pharyngeal consequences

of salivary hypofunction.

pharyngeal consequences.

The most common cause of salivary disorders is the use of prescription and

non-prescription medications.

Reports indicate that 80% of the most commonly prescribed medications

can cause xerostomia, with more than 400 medications associated with

salivary gland dysfunction as an adverse side-effect.

Because elderly people are more likely than the rest of the population to

take medications and are more vulnerable to their side-effects,

medication-induced xerostomia is not uncommon.

Drugs with anticholinergic effects are the most likely to produce

complaints of diminished salivary output and dry mouth.

Drugs that inhibit neurotransmitters from binding to salivary gland

membrane receptors, or that perturb ion transport pathways in the acinar

cell, may adversely affect the quality and quantity of salivary output.

Common categories of these drugs include:

1. Tricyclic antidepressants

2. Sedatives and tranquillizers

3. Antihistamines

4. Antihypertensives

5. Cytotoxics

6. Anti-Parkinsonism drugs

One treatment for head and neck cancers is external beam radiation,

which causes severe and permanent salivary hypofunction and results in

persistent complaints of xerostomia.

Radiation-induced destruction of the serous-producing salivary cells

occurs via apoptosis.

Within one week of the start of irradiation, a patient’s salivary output may

have declined by 60–90%, with no recovery occurring unless the total dose

to salivary tissues is less than 25 Gy.

Most patients receive therapeutic dosages that exceed 60 Gy, therefore

their salivary glands undergo atrophy and become fibrotic.

Numerous systemic medical conditions can cause or contribute to salivary gland

diseases.

Including:

1. Sjögren’s syndrome;

2. Diabetes mellitus;

3. Alzheimer’s disease; and

4. Dehydration

Sjögren’s syndrome is one of the most frequently encountered chronic

autoimmune connective tissue disorders and is the most common systemic

condition associated with xerostomia.

Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in primary and secondary forms.

Those patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome have salivary and lacrimal gland

involvement, with an associated decreased production of saliva and tears.

In secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, the disorder presents with other autoimmune

diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis and

scleroderma.

Epidemiological studies show that the prevalence and

severity of periodontal disease increases with age.

This is most likely the result of repeated episodes of active

destruction occurring over time rather than an intrinsic Evidence of

change associated with the ageing process itself. gingival

Periodontal changes attributable solely to advancing age recession in an

elderly patient

are not sufficient to account for tooth loss, especially in a

leading to

healthy adult.

exposure of

Gingival recession has been considered as an age change, root surfaces

but it is now known to be part of the clinical spectrum of and root caries.

periodontitis in which plaque is the main aetiological

agent.

There is no evidence that the

elderly are particularly susceptible

to periodontal disease, although

confounding variables such as

systemic diseases, reduced manual

dexterity, oral factors and

medications have an adverse effect

on periodontal health.

Poor oral hygiene observed in an older patient

attending geriatric day hospital

Age changes in teeth include

physiological wear with

superimposed changes in

morphology associated with

pathology, including attrition and

changes in the structure and

composition of the dental hard

tissues.

Toothwear of lower incisors in an elderly

patient (the dentine deposition

obliterating the pulp chamber).

Enamel

The enamel tends to become more

brittle and susceptible to chipping,

cracking and fracture.

It also becomes less permeable with

age, reflecting the ionic exchange

which occurs between enamel and the

oral environment throughout life. Staining of lower anterior

Darkening of the enamel and staining teeth in an elderly patient.

has also been described and may be

due to absorption of organic material.

Dentino-pulpal complex

The two main age-related changes in dentine are continued formation of

secondary dentine, resulting in reduction in size and in some cases

obliteration of the pulp chamber, and dentinal sclerosis associated with the

continued production of peritubular dentine.

Both of these processes are also associated with caries and toothwear.

Dentine sclerosis may affect the use of adhesive systems with dentine.

Sclerosis of radicular dentine tends to make the roots brittle and they may

fractureduring extraction.

It is also associated with increased translucency of the root.

This starts at the apex in the peripheral dentine just beneath the cementum

and extends inwards and coronally with increasing age.

Physiological age changes are as a result of

continued production of secondary

dentine.

This reduces the height of pulp horns,

makes the pulp shrink out of the crown

and anterior teeth, reduces the distance

between chamber roof and floor in

posterior teeth and causes the pulp to

Pulp chambers of a 70-year-old patient

narrow concentrically in roots. showing a reduction in depth of the pulp

chambers.

The diminishing pulp space can be further

complicated by the growth of irregular

calcifications around degenerating blood

vessels and nerve cells.

These changes usually comprise spheroid ‘pulp

stones’ in the coronal chamber and linear

deposits in the canals.

Radiographs may suggest that these changes

completely obliterate the pulp space, but they

are usually interspersed with soft tissue that

provides space and nutrition for microbial Pulp stones in maxillary molar teeth.

infection, whilst easing the path for operative

disruption and entry.

Pulps undergo physiological and reactive

changes as patients age.

Changes are not uniform and are not uniquely

concentrated in the chronologically old.

Pulp canals in the elderly are not necessarily

narrow and difficult to manage, and reactive

changes in the young and middle-aged can be

equally challenging.

As the pulp ages, it becomes less vascular, less

cellular and more fibrotic, resulting in a

reduced response to injury and decreased

healing potential.

There is also a reduced nerve supply which, together with a greater

thickness of dentine, makes vitality testing more difficult.

The tissue is tougher and may not be penetrated as easily with files.

The risk this presents is that entry, even to a seemingly large pulp, results

in compaction of pulp tissue to form a dense collagenous plug that is as

impregnable as any calcified deposit.

There is special merit in the elderly of removing pulp tissue with barbed

broaches and the routine use of lubricants to allow instruments to glide

through tissue rather than compacting it.

Cementum

Cementum continues to be formed throughout life, especially in the apical

half of the root, resulting in a gradual increase in thickness to compensate

for interproximal and occlusal attrition and in response to trauma, caries

and periodontal disease.

The amount of secondary cementum at the apex of a tooth is a factor that

can be taken into account in radiographic working length estimation in

endodontics, and in forensic dentistry in age estimation.

Increased amounts of cementum along with secondary and reparative

dentine diminish tooth sensitivity and reduce perception to painful

stimuli.

A variety of oral changes may be observed in elderly patients.

These changes can be attributed to a variety of physiological and

pathological processes which have developed over a lifetime.

Clinically, it is important to recognize these changes and to develop

planning strategies which take account of them.

Emphasis must be placed on preventive regimes and treatment delivery

which is sympathetic to the changing needs of our existing elderly and

ageing population.

Boucher’s prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients.(9th edition) -Zarb &

Bolender

Textbook of complete denture (5th edition) – Charles M Heartwell Jr & Rahn

Essentials of complete denture prosthodontics - Sheldon Winkler

Text book of Prosthodontics (2nd ed.) – V. Rangarajan & TV Padmanabhan

Gerald Mckenna & Francis M Burke ; Age-Related Oral Changes, Dent Update

2010; 37: 519–523

Laurence Mioche*, Pierre Bourdiol and Marie-Agnès Peyron ; Influence of age

on mastication: effects on eating behaviour, Nutrition Research Reviews (2004), 17,

43–54

You might also like

- Orthodontically Driven Corticotomy: Tissue Engineering to Enhance Orthodontic and Multidisciplinary TreatmentFrom EverandOrthodontically Driven Corticotomy: Tissue Engineering to Enhance Orthodontic and Multidisciplinary TreatmentFederico BrugnamiNo ratings yet

- Article-PDF-Ajay Gupta Bhawana Tiwari Hemant Gole Himanshu Shekhawat-56Document5 pagesArticle-PDF-Ajay Gupta Bhawana Tiwari Hemant Gole Himanshu Shekhawat-56Manjeev GuragainNo ratings yet

- Bone Loss Patterns and MechanismsDocument24 pagesBone Loss Patterns and MechanismsPrathik RaiNo ratings yet

- Bone LossDocument33 pagesBone LossMaitreyi LimayeNo ratings yet

- Effects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneDocument6 pagesEffects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Residual Ridge Resorpion With ManagementDocument47 pagesResidual Ridge Resorpion With ManagementAbhishek Gupta0% (1)

- Effect of Teeth Loss On Oro-Facial Environment: Done By: Khaled Hamed Alabd Alahmad ID: 201502300Document8 pagesEffect of Teeth Loss On Oro-Facial Environment: Done By: Khaled Hamed Alabd Alahmad ID: 201502300khaled alahmadNo ratings yet

- Tooth Loss222222Document8 pagesTooth Loss222222khaled alahmadNo ratings yet

- Resorptive Changes of Maxillary and Mandibular Bone Structures in Removable Denture WearersDocument5 pagesResorptive Changes of Maxillary and Mandibular Bone Structures in Removable Denture WearersAhmed SamirNo ratings yet

- 5 Exclusive Techniques - RESIDUAL RIDGE RESORPTION - ExtoothDocument18 pages5 Exclusive Techniques - RESIDUAL RIDGE RESORPTION - ExtoothHugo MoralesNo ratings yet

- Gedriadic EndoDocument26 pagesGedriadic EndoJitender Reddy100% (1)

- Residual Ridge Resorption in Complete Denture WearersDocument5 pagesResidual Ridge Resorption in Complete Denture WearersFiru LgsNo ratings yet

- Age ChangesDocument6 pagesAge ChangesCarissaNo ratings yet

- Residual Ridge Resorption (RRRDocument15 pagesResidual Ridge Resorption (RRRريام الموسويNo ratings yet

- Alveolar Process: Wandee Apinhasmit DDS, PHDDocument35 pagesAlveolar Process: Wandee Apinhasmit DDS, PHDVeerawit LukkanasomboonNo ratings yet

- Mariyam Zehra PG 1St Year Department of OrthodonticsDocument101 pagesMariyam Zehra PG 1St Year Department of OrthodonticsMariyam67% (3)

- Dr. Kartheek.G: Aging and its Effects on Oral TissuesDocument24 pagesDr. Kartheek.G: Aging and its Effects on Oral TissuesArif Mohiddin100% (1)

- Adult OrthodonticsDocument82 pagesAdult OrthodonticsUmang TripathiNo ratings yet

- Residual Ridge ResorptionDocument78 pagesResidual Ridge ResorptionsaksheeNo ratings yet

- Agging and The UmDocument39 pagesAgging and The UmNada EmamNo ratings yet

- Alveolar BoneDocument26 pagesAlveolar Bonelokesh_045No ratings yet

- A Review of Residual Ridge Resorption and Bone DensityDocument3 pagesA Review of Residual Ridge Resorption and Bone DensityrekabiNo ratings yet

- BONE LOSS AND PATTERNS OF BONE DESTRUCTION HDocument33 pagesBONE LOSS AND PATTERNS OF BONE DESTRUCTION Heimaan afrozNo ratings yet

- Alveolar BoneDocument47 pagesAlveolar BoneShashi kiranNo ratings yet

- Done By: Dr. Farah RagheedDocument34 pagesDone By: Dr. Farah Ragheedايه حسن عبد الرحمنNo ratings yet

- Changes Caused by A Mand RPD Opposing A Max CDDocument11 pagesChanges Caused by A Mand RPD Opposing A Max CDPakwan VarapongsittikulNo ratings yet

- Bone Loss & Patterns of Bone DestructionDocument55 pagesBone Loss & Patterns of Bone DestructionPrathik RaiNo ratings yet

- Changes Caused by A MCMD R Remov P4Bhkll Denture Oppesing A Muxitkwy Compbe De&WeDocument11 pagesChanges Caused by A MCMD R Remov P4Bhkll Denture Oppesing A Muxitkwy Compbe De&WeERIKA BLANQUETNo ratings yet

- Paget's disease presenting with root resorptionDocument4 pagesPaget's disease presenting with root resorptionNurani AtikasariNo ratings yet

- Residual Ridge ResorptionDocument13 pagesResidual Ridge ResorptionsankarNo ratings yet

- Vertical and Horizontal Augmentation of Deficient Maxilla and Mandible For Implant Placement. Amanda AndreDocument21 pagesVertical and Horizontal Augmentation of Deficient Maxilla and Mandible For Implant Placement. Amanda AndreAmani Fezai100% (1)

- Residual Ridge ResorptionDocument91 pagesResidual Ridge ResorptionAME DENTAL COLLEGE RAICHUR, KARNATAKA100% (2)

- Bone & Joint Pathology GuideDocument8 pagesBone & Joint Pathology Guidelovelyc95No ratings yet

- Ijpi 2 (4) 136-140Document5 pagesIjpi 2 (4) 136-140salman khawarNo ratings yet

- K32 - Pathology of Bone (Dr. Dody)Document60 pagesK32 - Pathology of Bone (Dr. Dody)faris100% (1)

- Pagets DiseaseDocument62 pagesPagets DiseaseKush PathakNo ratings yet

- Nms 2 - 3 - OsteoarthritisDocument52 pagesNms 2 - 3 - OsteoarthritisAngga FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Effects of Aging Edentulous PatientDocument29 pagesEffects of Aging Edentulous PatientMaliha TahirNo ratings yet

- AGINGDocument6 pagesAGINGnusreenNo ratings yet

- Internal and External Changes in The Edentulous MandibleDocument7 pagesInternal and External Changes in The Edentulous MandibleEm EryNo ratings yet

- Httpsamoodle - Su.edu - Egpluginfile.php202864mod Resourcecontent1Lecture20120 Bone20diseas20 PDFDocument7 pagesHttpsamoodle - Su.edu - Egpluginfile.php202864mod Resourcecontent1Lecture20120 Bone20diseas20 PDFtthtn6c8pbNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of OrthodonticDocument43 pagesBasic Principles of Orthodonticbob0% (1)

- Metabolic Jaw DiseasesDocument55 pagesMetabolic Jaw DiseasesoladunniNo ratings yet

- Age Changes IN Oral Tissues: Indian Dental AcademyDocument79 pagesAge Changes IN Oral Tissues: Indian Dental AcademyhazeemmegahedNo ratings yet

- Age Changes in Oral TissueDocument34 pagesAge Changes in Oral TissueAiswarya MishraNo ratings yet

- 11-Metabolic &genetic Bone DiseasesDocument12 pages11-Metabolic &genetic Bone Diseasesفراس الموسويNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Bone DiseasesDocument55 pagesMetabolic Bone DiseasesJk FloresNo ratings yet

- Week 12 Article 1 BrickleyDocument16 pagesWeek 12 Article 1 BrickleyJean-Claude TissierNo ratings yet

- Bone Loss and Patterns of Bone DestructionDocument5 pagesBone Loss and Patterns of Bone Destructionnimisha kakkadNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Gingiva and Um - Pros Tho Don Tic SignificanceDocument108 pagesAnatomy of Gingiva and Um - Pros Tho Don Tic SignificanceDilip Singh100% (1)

- Aging and The Periodontium Lectu 5Document21 pagesAging and The Periodontium Lectu 5Anoos rabayarabayaNo ratings yet

- Gambar Radiologi Semester 5Document15 pagesGambar Radiologi Semester 5Faidhi Rahman HafizhNo ratings yet

- The Aetiology of Gingival RecessionDocument4 pagesThe Aetiology of Gingival RecessionshahidibrarNo ratings yet

- Management of Residual Ridge Reduction (RRR)Document23 pagesManagement of Residual Ridge Reduction (RRR)drmohitmalviyaNo ratings yet

- 3.the Remodeling of The Edentulous MandibleDocument9 pages3.the Remodeling of The Edentulous MandibleNathawat PleumsamranNo ratings yet

- Maxillofacial fibro-osseous lesionsDocument30 pagesMaxillofacial fibro-osseous lesionsnaidu.harikaa15No ratings yet

- Westjmed00101 0065Document15 pagesWestjmed00101 0065zarrougonesNo ratings yet

- Periodontal SurgeriesDocument46 pagesPeriodontal SurgeriesnutacosmynNo ratings yet

- SurveyingDocument78 pagesSurveyingankitaNo ratings yet

- Comparing The Vertical Misfit of Casts Produced by Two Verificati PDFDocument51 pagesComparing The Vertical Misfit of Casts Produced by Two Verificati PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- Good Maxillofacial ArticleDocument11 pagesGood Maxillofacial Articledrchabra dentalNo ratings yet

- Muscles of Mastication FarhanDocument117 pagesMuscles of Mastication FarhanankitaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Flap DesignDocument8 pagesPrinciples of Flap Designalkhalijia dentalNo ratings yet

- Centric RelationDocument7 pagesCentric RelationHarish KumarNo ratings yet

- Immediate Implant Loading - A Paradigm Shift PDFDocument4 pagesImmediate Implant Loading - A Paradigm Shift PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- BJSTR MS Id 004390 PDFDocument3 pagesBJSTR MS Id 004390 PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- Management of Implant Abutment Screw Fracture Using A Non Invasive Technique 9 Months Follow Up Case Report - 1598628350 PDFDocument7 pagesManagement of Implant Abutment Screw Fracture Using A Non Invasive Technique 9 Months Follow Up Case Report - 1598628350 PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- The Neutral Zone Concept in Complete DentureDocument122 pagesThe Neutral Zone Concept in Complete Denturevahini niharikaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition For Geriatric Complete Denture Wearing Patients: February 2020Document7 pagesNutrition For Geriatric Complete Denture Wearing Patients: February 2020ankitaNo ratings yet

- Single Tooth Implant Placement in Anterior Maxilla PDFDocument5 pagesSingle Tooth Implant Placement in Anterior Maxilla PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- DentigenicsinCompleteDentureProsthodontics PDFDocument106 pagesDentigenicsinCompleteDentureProsthodontics PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- Implant Success, Survival, and Failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus ConferenceDocument11 pagesImplant Success, Survival, and Failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus ConferenceankitaNo ratings yet

- Biohazards in DentistryDocument4 pagesBiohazards in DentistryankitaNo ratings yet

- Case Report on Full Mouth Rehabilitation of Worn Dentition Using Segmental Arch TechniqueDocument4 pagesCase Report on Full Mouth Rehabilitation of Worn Dentition Using Segmental Arch TechniqueankitaNo ratings yet

- Dental Ceramics Part I - An Overview of Composition, Structure and PropertiesDocument6 pagesDental Ceramics Part I - An Overview of Composition, Structure and PropertiesLinda Garcia PNo ratings yet

- Herapeutic Iomechanics Oncepts and Linical Rocedures To Educe Mplant Oading ARTDocument9 pagesHerapeutic Iomechanics Oncepts and Linical Rocedures To Educe Mplant Oading ARTankitaNo ratings yet

- IPS E-Max Clinical Guide PDFDocument44 pagesIPS E-Max Clinical Guide PDFKarolis KNo ratings yet

- Nutrition For Geriatric Complete Denture Wearing Patients: February 2020Document7 pagesNutrition For Geriatric Complete Denture Wearing Patients: February 2020ankitaNo ratings yet

- Implants in Maxillofacial Prosthodontics PDFDocument50 pagesImplants in Maxillofacial Prosthodontics PDFankita50% (2)

- BiocompatibityDocument19 pagesBiocompatibityamlniNo ratings yet

- 1158 PDFDocument7 pages1158 PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Treatment Planning of Mandibular Implant OverdentureDocument5 pagesGuidelines For Treatment Planning of Mandibular Implant OverdentureankitaNo ratings yet

- Wound Healing Problems in The Mouth: Constantinus Politis, Joseph Schoenaers, Reinhilde Jacobs and Jimoh O. AgbajeDocument13 pagesWound Healing Problems in The Mouth: Constantinus Politis, Joseph Schoenaers, Reinhilde Jacobs and Jimoh O. AgbajeankitaNo ratings yet

- 490.135-En Low PDFDocument16 pages490.135-En Low PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- Concept Complete ExamDocument5 pagesConcept Complete ExamankitaNo ratings yet

- JDentAlliedSci7270-5544056 152400 PDFDocument5 pagesJDentAlliedSci7270-5544056 152400 PDFankitaNo ratings yet

- L. D.D.S., M.Sc. : Anatomy of Facial Expression AND Its Prosthodontic SignificanceDocument23 pagesL. D.D.S., M.Sc. : Anatomy of Facial Expression AND Its Prosthodontic SignificanceankitaNo ratings yet

- NCP Impaired Oral Mucous MembraneDocument2 pagesNCP Impaired Oral Mucous Membraneklemtot83% (6)

- Group 3 Sjogrens SyndromeDocument9 pagesGroup 3 Sjogrens SyndromeFrancine LerioNo ratings yet

- Prosthodontics by Prof. Sajid NaeemDocument211 pagesProsthodontics by Prof. Sajid NaeemFA Khan50% (2)

- SalivaDocument102 pagesSalivacareNo ratings yet

- Management and Prevention of Complications During Initial Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer - UpToDateDocument19 pagesManagement and Prevention of Complications During Initial Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer - UpToDateAchmad MusaNo ratings yet

- Background: ParotitisDocument23 pagesBackground: ParotitisifahInayah100% (1)

- Dry Mouth English May2019 ١Document8 pagesDry Mouth English May2019 ١العمري العمريNo ratings yet

- Cavum Oris Dan Galndula SalivariusDocument26 pagesCavum Oris Dan Galndula SalivariusAisyah FawNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Oral Medicine Oral Diagnosis and Oral RadiologyDocument924 pagesTextbook of Oral Medicine Oral Diagnosis and Oral RadiologyAnonymous Bt6favSF4Y90% (67)

- Dysphagia After Total LaryngectomyDocument6 pagesDysphagia After Total LaryngectomyEduardo Lima de Melo Jr.No ratings yet

- Buffering Capacity of SalivaDocument51 pagesBuffering Capacity of SalivaYoonho LeeNo ratings yet

- SalivaDocument42 pagesSalivaAtharva KambleNo ratings yet

- Zecha 2016Document13 pagesZecha 2016Maria Carolina MussiNo ratings yet

- BATMANGHELIDJ, Dr. F - Your Body's Many Cries For Water (2000) PDFDocument187 pagesBATMANGHELIDJ, Dr. F - Your Body's Many Cries For Water (2000) PDFvperez100% (13)

- Defense Mechanism of GingivaDocument36 pagesDefense Mechanism of GingivaPiyusha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Radiotherapy in Management of Head and Neck CancerDocument51 pagesRadiotherapy in Management of Head and Neck CancerKassim OboghenaNo ratings yet

- Atrofi MukosaDocument59 pagesAtrofi MukosaFaiza LailiyahNo ratings yet

- 6302823Document84 pages6302823drvivek reddyNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry of GIT by MedicneticDocument8 pagesBiochemistry of GIT by MedicneticDivine GamingNo ratings yet

- Medical Terminology ١Document34 pagesMedical Terminology ١Spotify IraqNo ratings yet

- The Retention of Complete DentureDocument15 pagesThe Retention of Complete DentureAmit ShivrayanNo ratings yet

- Your Complete Guide To DysphagiaDocument36 pagesYour Complete Guide To DysphagiaFabiola NogaNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 4 Social Studies Worksheet - Means of TransportDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 4 Social Studies Worksheet - Means of TransportNancy Amelia RosaNo ratings yet

- Burning Mouth Disease A Guide For Patients (Isaäc Van Der Waal)Document50 pagesBurning Mouth Disease A Guide For Patients (Isaäc Van Der Waal)x9mg58srbyNo ratings yet

- 5043 14437 1 PB PDFDocument9 pages5043 14437 1 PB PDFvivi hutabaratNo ratings yet

- Post Insertion Problems in Complete Denture: A Review: IP Annals of Prosthodontics and Restorative DentistryDocument5 pagesPost Insertion Problems in Complete Denture: A Review: IP Annals of Prosthodontics and Restorative DentistrySharon LawNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations of Systemic DiseasesDocument11 pagesOral Manifestations of Systemic DiseasesMezo Salah100% (2)

- Von Stein 2019Document7 pagesVon Stein 2019Meylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- DVH LimitsDocument1 pageDVH LimitsDioni SandovalNo ratings yet

- Sjogren Syndrome: Schirmer TestDocument2 pagesSjogren Syndrome: Schirmer TestRiena Austine Leonor NarcillaNo ratings yet