Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dischargeability of Nonpriority Taxes For Late-Filed Tax Return

Dischargeability of Nonpriority Taxes For Late-Filed Tax Return

Uploaded by

Keenan SmithOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dischargeability of Nonpriority Taxes For Late-Filed Tax Return

Dischargeability of Nonpriority Taxes For Late-Filed Tax Return

Uploaded by

Keenan SmithCopyright:

Available Formats

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

38-SEP Am. Bankr. Inst. J. 14

American Bankruptcy Institute Journal

September, 2019

Consumer Corner

John N. Tedford, IV a1

Danning, Gill, Diamond & Kollitz, LLP

Los Angeles

Copyright © 2019 by American Bankruptcy Institute; John N. Tedford, IV

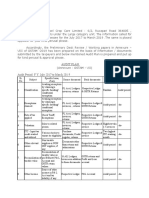

*14 DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR LATE-FILED

TAX RETURN

Priority tax claims are nondischargeable. Whether a nonpriority tax claim is dischargeable largely depends on whether and

when the debtor filed a tax return. Unfortunately, it also depends on where the debtor lives because courts cannot agree on the

answer to this seemingly simple question: For purposes of § 523(a)(1)(B), what is a “return”?

Dischargeability of Taxes

Since 1966, Congress has sought to balance a debtor's need for a fresh start, policies favoring equitable distributions among

unsecured creditors, and the government's need for sufficient time to conduct its auditing, assessment and collection functions.

Today, § 523(a)(1)(B) provides that a discharge does not discharge a nonpriority tax

with respect to which a return, or equivalent report or notice, if required--

(i) was not filed or given; or

(ii) was filed or given after the date on which such return, report, or notice was last due, under applicable law or

under any extension, and after two years before the date of the filing of the petition.

Section 523(a)(1)(B) serves two purposes: (1) It discourages debtors from using bankruptcy as a tax-evasion device; and (2)

it gives the government at least two years to audit returns, assess deficiencies and collect taxes or create liens before the taxes

may be discharged. It requires only objective analyses, referencing easily discernable facts and requiring no inquiry into the

debtor's motives.

Early Decisions

At least at first, courts had little trouble applying § 523(a)(1)(B). The only truly difficult cases arose when debtors argued

that returns prepared by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) under § 6020 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), or stipulated

judgments entered in tax courts, constituted “returns” for purposes of § 523(a)(1)(B).

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

When a taxpayer fails to timely file a proper return, the IRS prepares a substitute return under IRC § 6020(a) or (b). Under

IRC § 6020(a), a taxpayer provides the IRS with the information needed to prepare the return. Once it is signed, the IRS may

accept it as the taxpayer's return. Generally, courts have held that returns prepared under IRC § 6020(a) qualify as “returns”

for purposes of § 523(a)(1)(B). 1

Under IRC § 6020(b), the IRS prepares the substitute return using information from third parties. The IRS gives notice of its

proposed assessment, and the taxpayer has 90 days to file a petition with the tax court to challenge the proposed assessment. 2

If no petition is filed, the IRS makes an assessment in the proposed amount. 3 Almost universally, courts have held that returns

prepared under IRC § 6020(b) do not qualify as “returns.” 4 Similarly, at least one court has held that a settlement resulting in

entry of a stipulated tax court decision did not qualify as a “return.” 5

Other than in these situations, courts did not struggle with defining “return.” As one put it, “The plain meaning of the word

‘return’ should be conclusive, as it has a very specific meaning in the world of taxation. Certainly, taxpayers know what it means

to have to file a tax return; they do it each year.” 6 A debtor's motives were irrelevant. However, that began to change in 1997

when courts began using the Beard test to determine whether late-filed returns qualified as returns under § 523(a)(1)(B).

The Beard Test

To determine whether a document qualifies as a “return,” federal courts follow the “Beard test” formulated by the U.S. Tax

Court in 1984 from two depression-era Supreme Court cases. 7 Under the Beard test:

(1) there must be sufficient data to calculate tax liability;

(2) the document must purport to be a return;

(3) there must be an honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax law; and

(4) the taxpayer must execute the return under penalty of perjury.

*15 After formulating the test, the Beard court discussed “[t]he most recent Supreme Court reaffirmation of the test”:

Badaracco v. Commissioner. 8 In that case, taxpayers filed fraudulent returns, but later filed nonfraudulent amended returns.

The Supreme Court ruled that “the original returns ... purported to be returns, were sworn to as such, and appeared on their

faces to constitute endeavors to satisfy the law.” 9 Thus, although indisputably fraudulent, the documents were returns.

Beard involved a taxpayer who, in protest, tampered with his Form 1040. The tax court held that the impermissibly modified

form was not a return. Badaracco and Beard illustrate how the third prong of the Beard test should be applied. Instinctively,

a taxpayer who files a fraudulent return has not made an “honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax

law.” However, Badaracco shows that this instinct is wrong. The third prong should be determined by reference to the face of

the document, not to the filer's motive.

Post-Assessment Approach

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

The Beard test went mostly unnoticed in bankruptcy cases until 1997. In In re Hindenlang, the IRS prepared substitute returns

under IRC § 6020(b), sent deficiency notices to which the debtor did not respond, and assessed taxes. After the taxes were

assessed, the debtor filed returns. More than two years later, he filed for bankruptcy. Applying the Beard test, the bankruptcy

court held that the taxes were discharged because returns were filed more than two years pre-petition. 10

The Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that a purported return filed too late to have any effect under the IRC cannot, as a matter

of law, constitute an “honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax law.” 11 Because the debtor could

not identify any tax purpose for his late-filed Form 1040s, the court ruled that they were not “returns,” therefore the taxes were

nondischargeable.

In a similar case, the Fourth Circuit reached the same result, but for a different reason: “Simply put, to belatedly accept

responsibility for one's tax liabilities, only when the IRS has left one with no other choice, is hardly how honest and reasonable

taxpayers attempt to comply with the [T]ax [C]ode.” 12 The court declined to expressly hold that a post-assessment return can

never qualify as a return, but shifted the burden to the debtor to prove that he/she made an honest and reasonable attempt to

comply with the tax law.

The approach by the Sixth and Fourth Circuits is referred to as the “post-assessment approach.” Theoretically, debtors can

attempt to explain that they made honest and reasonable attempts to comply with tax laws. However, in practice, the post-

assessment approach renders nondischargeable almost any tax for which a return was filed after the tax was assessed.

*58 Totality-of-the-Circumstances Approach

In the late 1990s, the Ninth Circuit Bankruptcy Appellate Panel (BAP) ruled in In re Hatton that a debtor provided the equivalent

of a return by acknowledging the tax assessed by the IRS after it prepared a substitute return under IRC § 6020(b), and by

entering into an installment agreement to pay the tax over time. 13 The Ninth Circuit reversed, ruling that neither the substitute

return nor the installment agreement constituted a “return” of a kind that would permit a discharge of the debt. 14 Since neither

document was signed under penalty of perjury, the fourth prong of the Beard test was clearly not met. However, the court found

that the third prong was also not satisfied because the debtor “made every attempt to avoid paying his taxes until the IRS left

him with no other choice.” 15

The Ninth Circuit cited Hindenlang but did not follow the post-assessment approach. Instead, the court conducted a more

comprehensive inquiry of the facts. Subsequent cases in the Ninth Circuit correctly follow Hatton by examining all relevant facts

and circumstances pertaining to the honesty and reasonableness of the debtors' efforts. 16 Thus, the Ninth Circuit's approach

is referred to as the totality-of-the-circumstances approach.

No-Time-Limit Approach

In In re Colsen, the debtor filed five years' worth of tax returns post-assessment. The bankruptcy court, BAP and Eighth Circuit

all agreed that whether a document constitutes a return must be viewed objectively, as the Supreme Court did in Badaracco. 17

Alas, “the honesty and genuineness of the filer's attempt to satisfy the tax laws should be determined from the face of the form

itself, not from the filer's delinquency or the reasons for it.” 18 Because the time of filing is irrelevant, this is referred to as

the no-time-limit approach.

Functional Approach

In 2005, the Seventh Circuit adopted a functional approach to determining whether a document is a return. Writing for the

majority, Hon. Richard Posner wrote that “there is no reason why the word ‘return’ ... should carry the same meaning regardless

of context.” 19 A document can be considered a return in one context to discourage fraud (such as in Badaracco), but not

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

considered a return in the bankruptcy context “to discourage people from using bankruptcy law to avoid having to satisfy their

tax liabilities.” 20

Hon. Frank Easterbrook filed a notable dissent. Following the no-time-limit approach, he would have held the taxes as

dischargeable simply because the document filed with the IRS contained all required information and was filed more than two

years pre-petition. 21

BAPCPA's Addition of § 523(a)(*)

In 2005, the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA) added a hanging paragraph at the end of

§ 523(a) (a.k.a. § 523(a)(*)):

For purposes of [§ 523(a)], the term “return” means a return that satisfies the requirements of applicable

nonbankruptcy law (including applicable filing requirements). Such term includes a return prepared pursuant to

[IRC § 6020(a)], or similar State or local law, or a written stipulation to a judgment or a final order entered by

a nonbankruptcy tribunal, but does not include a return made pursuant to [IRC § 6020(b)], or a similar State or

local law.

The sparse legislative history of § 523(a)(*) suggests that it was meant only to resolve three basic questions. For purposes of

§ 523(a)(1), (1) is a return prepared under IRC § 6020(a) (with the taxpayer's help) a return; (2) is a substitute return prepared

under IRC § 6020(b) (without the taxpayer's help) a return; and (3) if a debtor contests a proposed assessment but later agrees

to a stipulated decision regarding *59 the tax owed, is that a return? There is nothing to suggest that § 523(a)(*) was intended

to adopt--or reject--any particular approach to defining “return.” Unfortunately, while resolving these three questions, § 523(a)

(*)--particularly the parenthetical phrase “including applicable filing requirements”--exacerbated the debate over whether late-

filed returns constitute returns for purposes of § 523(a)(1).

Initial Reactions

One of the first cases to examine § 523(a)(*) concluded that it “apparently means that a late-filed income tax return, unless it

was filed pursuant to [IRC § 6020(a)], can never qualify as a return for dischargeability purposes because it does not comply

with the ‘applicable filing requirements' set forth in the [IRC].” 22 Numerous lower courts concurred, and some have ruled that

§ 523(a)(*) supplanted the Beard test. 23 Others disagreed, however. As expressed by the Tenth Circuit BAP:

Each of the two sentences in [§ 523(a)(*)] appears quite straightforward when standing alone. However, when

the two are read together, we are not convinced ... that the precise meaning and effect of the hanging paragraph

is clear .... Our own research has uncovered nothing to support the conclusion that the hanging paragraph was

intended to create the rule that a late-filed federal income tax return can never lead to discharge unless it ... is

prepared pursuant to IRC § 6020(a) or similar provision. 24

Some courts have opined that interpreting § 523(a)(*) that way would make § 523(a)(1)(B)(ii) superfluous or insignificant, 25

and others have noted that if late-filed returns are never “returns,” there was no need for Congress to specify that substitute

returns prepared under IRC § 6020(b) are not returns. 26

One-Day-Late Approach

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

In In re McCoy, the Fifth Circuit agreed with the first group of post-BAPCPA cases and held that a late-filed state tax return is

not a return for purposes of § 523(a) unless it is filed under a “safe harbor” provision similar to IRC § 6020(a). 27 The Tenth

Circuit followed suit in In re Mallo, ruling that § 523(a)(*) “plainly excludes late-filed Form 1040s from the definition of a

return.” 28 The First Circuit reached the same conclusion in In re Fahey. 29 This approach is referred to as the one-day-late

approach because it renders a tax nondischargeable if the return is filed as little as one day late.

Both debtors and the IRS consistently urge courts to reject the one-day-late approach. From the IRS's perspective, it eliminates

an incentive for debtors to file tax returns after they are due. It also burdens the IRS by increasing the number of taxpayers who

ask the IRS to prepare returns pursuant to IRC § 6020(a). At least one court found McCoy's conclusions “troubling particularly

because the IRS does not agree with [its] position.” 30

Other Circuits

The Ninth Circuit is the only circuit to have rejected the one-day-late approach. In In re Martin, the Ninth Circuit BAP

commented that “[t]he more one considers the phrase ‘applicable filing requirements' in context, the more doubtful the

literal construction becomes.” 31 In a subsequent case, the Ninth Circuit continued to apply its pre-BAPCPA totality-of-the-

circumstances approach, implicitly rejecting the one-day-late approach. 32

Both the Third and Eleventh Circuits have so far expressly declined to accept or reject the one-day-late approach. 33 The Eighth

Circuit has not yet ruled on whether § 523(a)(*) abrogated its no-time-limit approach.

IRS Approach

Further complicating matters, the IRS advocates for an approach that does not rely on any definition of “return.” According

to the IRS, when a taxpayer files a return after the IRS makes an assessment, the debt is based on the assessment, not on the

return. 34 The IRS contends that the tax is therefore not a debt “with respect to which a [required] return” was filed, and is

therefore nondischargeable under § 523(a)(1)(B)(i). The IRS approach is most similar to the post-assessment approach, and in

most cases it achieves the same result: It has been rejected by almost every court to consider it. 35

Conclusion

The no-time-limit approach adopted by the Eighth Circuit in Colsen is most consistent with Badaracco, gives full effect to

§ 523(a)(1) and (*), and maintains the balance struck more than 50 years ago between the debtor's need for a fresh start and

the government's need for sufficient time to conduct its auditing, assessment and collection functions. For debtors who file

returns even a single day late, the one-day-late approach leaves them “saddled with a continued liability for ... taxes until the

last lingering echo of Gabriel's horn trembles into ultimate silence.” 36 There is nothing in BAPCPA's legislative history to

suggest that Congress intended for § 523(a)(*) to have this effect.

Footnotes

a1 John Tedford is a partner with Danning, Gill, Diamond & Kollitz, LLP in Los Angeles.

1 See, e.g., In re Lowrie, 162 B.R. 864 (Bankr. D. Nev. 1994).

2

26 U.S.C. §§ 6212(a), 6213(a).

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

3

26 U.S.C. §§ 6203, 6213(c).

4

See, e.g., In re Hofmann, 76 B.R. 853 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 1987).

5

See In re Gushue, 126 B.R. 202 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 1991).

6

In re Jerauld, 208 B.R. 183, 188 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 1997).

7

Beard v. Comm'r, 82 T.C. 766 (1984) (citing Florsheim Bros. Drygoods Co. v. U.S., 280 U.S. 453 (1930);

Zellerbach Paper Co. v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 172 (1934)).

8

Badaracco v. Comm'r, 464 U.S. 386 (1984).

9

Id. at 397 (emphasis added).

10

In re Hindenlang, 205 B.R. 874, 878 (Bankr. S.D. Ohio 1997).

11

In re Hindenlang, 164 F.3d 1029, 1034-35 (6th Cir. 1999).

12

In re Moroney, 352 F.3d 902, 906 (4th Cir. 2003).

13

In re Hatton, 216 B.R. 278 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 1997).

14

In re Hatton, 220 F.3d 1057 (9th Cir. 2000).

15

Id. at 1061.

16

See, e.g., In re Martin, 542 B.R. 479, 491 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 2015).

17

In re Colsen, 311 B.R. 765 (Bankr. N.D. Iowa 2004); In re Colsen, 322 B.R. 118 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2005); In re Colsen,

446 F.3d 836 (8th Cir. 2006).

18

Colsen, 446 F.3d at 840.

19

In re Payne, 431 F.3d 1055, 1058 (7th Cir. 2005).

20

Id. at 1059.

21

Id. at 1062-63.

22

In re Creekmore, 401 B.R. 748, 751 (Bankr. N.D. Miss. 2008).

23 See, e.g., In re Casano, 473 B.R. 504, 507 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 2012).

24

In re Wogoman, 475 B.R. 239, 248-249 (B.A.P. 10th Cir. 2012).

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6

Smith, Keenan 10/15/2020

For Educational Use Only

DISCHARGEABILITY OF NONPRIORITY TAXES FOR..., 38-SEP Am. Bankr....

25

See, e.g., In re Brown, 489 B.R. 1, 5 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2013).

26

See, e.g., In re Gonzalez, 506 B.R. 317, 328 (B.A.P. 1st Cir. 2014).

27

In re McCoy, 666 F.3d 924, 932 (5th Cir. 2012).

28

In re Mallo, 774 F.3d 1313, 1321 (10th Cir. 2014). Notably, the court would have adopted the no-time-limit approach

but for § 523(a)(*).

29

Fahey v. Mass. Dept. of Rev., 779 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2015).

30 In re Coyle, 524 B.R. 863, 867 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2015).

31

Martin, 542 B.R. at 487.

32 In re Smith, 828 F.3d 1094, 1096-97 (9th Cir. 2016).

33

See In re Giacchi, 856 F.3d 244, 247-48 (3d Cir. 2017); In re Justice, 817 F.3d 738, 743 (11th Cir. 2016).

34 See IRS Chief Counsel Notice 2010-016 (Sept. 2, 2010).

35

See, e.g., In re Rhodes, 498 B.R. 357, 362 (Bankr. N.D. Ga. 2013); but see In re Pitts, 497 B.R. 73 (Bankr. C.D.

Cal. 2013).

36 Discharge of Taxes in Bankruptcy: Hearing on S. 976 (H.R. 3438) and S. 1912 (H.R. 136) Before the S. Comm. on

Finance, 89th Cong. 21 (1965) (statement of Sen. Sam J. Ervin).

38-SEP AMBKRIJ 14

End of Document © 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government

Works.

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Citizens United FOIA Production #1 (Veterans Affairs - Biden Voting EO)Document90 pagesCitizens United FOIA Production #1 (Veterans Affairs - Biden Voting EO)Citizens UnitedNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Stetson 2005 ExamDocument11 pagesStetson 2005 ExamKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Teaching Augustine PDFDocument181 pagesTeaching Augustine PDFKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Suggested Answers To The 2016 Bar Examination in Labor LawDocument12 pagesSuggested Answers To The 2016 Bar Examination in Labor Lawaliagamps411No ratings yet

- Local Government SystemDocument65 pagesLocal Government Systemshakeel100% (1)

- The Roles and Powers of The LEGISLATIVE BRANCH of The Philippine GovernmentDocument24 pagesThe Roles and Powers of The LEGISLATIVE BRANCH of The Philippine GovernmentroperNo ratings yet

- Remedies 2002 Model AnswersDocument9 pagesRemedies 2002 Model AnswersKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property Rights LawDocument26 pagesIntellectual Property Rights LawEthereal DNo ratings yet

- Constitutions, Statutes, and Administrative RegulationsDocument30 pagesConstitutions, Statutes, and Administrative RegulationsKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Stetson-2002 AnswerDocument12 pagesStetson-2002 AnswerKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Income Tax OutlineDocument20 pagesIncome Tax OutlineKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Criminal LAW Bulletin: Volume 46, Number 2Document12 pagesCriminal LAW Bulletin: Volume 46, Number 2Keenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Fall 2006 ExamDocument10 pagesFall 2006 ExamKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Lesson 18 PowerpointDocument10 pagesLesson 18 PowerpointKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Updates: OK To Skip QP, BA & FactsDocument19 pagesSyllabus Updates: OK To Skip QP, BA & FactsKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Lesson 20 PowerpointDocument14 pagesLesson 20 PowerpointKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Jones V Golden PDFDocument7 pagesJones V Golden PDFKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- United States District Court Southern District of Ohio Western DivisionDocument27 pagesUnited States District Court Southern District of Ohio Western DivisionKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Question Presented & Brief Answer: Jackson - Legal Writing - Fall 2019Document1 pageQuestion Presented & Brief Answer: Jackson - Legal Writing - Fall 2019Keenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Absolute and Qualified ImmunityDocument6 pagesAbsolute and Qualified ImmunityKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Endo PR Fall 2020 SyllabusDocument8 pagesEndo PR Fall 2020 SyllabusKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- Substance v. Procedure ProblemDocument2 pagesSubstance v. Procedure ProblemKeenan SmithNo ratings yet

- 9 - GR No.225442-SPARK V Quezon CityDocument1 page9 - GR No.225442-SPARK V Quezon CityPamela Jane I. TornoNo ratings yet

- Agapay v. Palang, GR 116668, July 28, 1997Document18 pagesAgapay v. Palang, GR 116668, July 28, 1997Anna NicerioNo ratings yet

- Eng 7136Document4 pagesEng 7136sfsdfsdfsdfNo ratings yet

- Notes For MechDocument3 pagesNotes For MechShranish KarNo ratings yet

- Lankabangla Securities LTD.: Trade Confirmation Note (Summary)Document1 pageLankabangla Securities LTD.: Trade Confirmation Note (Summary)Mahi ZabeenNo ratings yet

- გაიქეცი პატარავ გაიქეცი PDFDocument260 pagesგაიქეცი პატარავ გაიქეცი PDFNino BerdzenishviliNo ratings yet

- Work Terms and ConditionsDocument3 pagesWork Terms and ConditionsYubaraj AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Recruitment For The Post of AssistantDocument4 pagesRecruitment For The Post of AssistantPradeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Rosencor Dev. Corp. v. Inquing, G.R. No. 140479Document10 pagesRosencor Dev. Corp. v. Inquing, G.R. No. 140479Shaula FlorestaNo ratings yet

- Subject: Issuance of Equivalence Certificate of MBA (3.5) To MBA/MS/M. PhillDocument1 pageSubject: Issuance of Equivalence Certificate of MBA (3.5) To MBA/MS/M. PhillAbdulBasitKhanSadozaiNo ratings yet

- Account Statement From 8 Jan 2021 To 8 Jul 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument16 pagesAccount Statement From 8 Jan 2021 To 8 Jul 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceMUTHYALA NEERAJANo ratings yet

- Starkville Dispatch Eedition 3-4-21Document12 pagesStarkville Dispatch Eedition 3-4-21The DispatchNo ratings yet

- 2018 Judgement 07-Mar-2019Document24 pages2018 Judgement 07-Mar-2019ajay kumarNo ratings yet

- Audit Plan: Note # 1Document6 pagesAudit Plan: Note # 1Audit Circle IV BhavnagarNo ratings yet

- Memo On Tree PlantingDocument6 pagesMemo On Tree Plantingjojo zamNo ratings yet

- Florentino v. Encarnacion G.R. No. L-27696, 30 September 1977 FactsDocument4 pagesFlorentino v. Encarnacion G.R. No. L-27696, 30 September 1977 FactsKNo ratings yet

- ADR Under Sec 89 of Civil Procedure Code, 1908: A Critical AnalysisDocument3 pagesADR Under Sec 89 of Civil Procedure Code, 1908: A Critical AnalysisSatyam SinghNo ratings yet

- OMBC Memoradum No. 2Document7 pagesOMBC Memoradum No. 2Shienna Divina GordoNo ratings yet

- Presentation JMCTIDocument42 pagesPresentation JMCTIyeyagoj460No ratings yet

- Pawar's Time of Reckoning - Outlook India MagazineDocument11 pagesPawar's Time of Reckoning - Outlook India MagazinelakshmankannaNo ratings yet

- Model-N-TR1EB SKD - 6090.199.009Document6 pagesModel-N-TR1EB SKD - 6090.199.009Wang Sze ShianNo ratings yet

- Law of CarriageDocument10 pagesLaw of CarriageSushree Swagatika BarikNo ratings yet

- NYPD Lieutenant Acquitted of Beating Girlfriend After OrgyDocument1 pageNYPD Lieutenant Acquitted of Beating Girlfriend After Orgyedwinbramosmac.comNo ratings yet

- Reyes vs. Enriquez Reyes vs. EnriquezDocument11 pagesReyes vs. Enriquez Reyes vs. EnriquezSamantha AdduruNo ratings yet

- Dont Ask Dont TellDocument4 pagesDont Ask Dont TellEmily CoxNo ratings yet