Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Space and Convention in Eugène Fromentin The Algerian Experience Christin1984

Uploaded by

Eric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Space and Convention in Eugène Fromentin The Algerian Experience Christin1984

Uploaded by

Eric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashCopyright:

Available Formats

""W!

lrnE JOHNS HOPKINS y ' I 'VE ' SITY RESS

Space and Convention in Eugène Fromentin: The Algerian Experience

Author(s): Anne-Marie Christin and Richard M. Berrong

Source: New Literary History, Vol. 15, No. 3, Image/Imago/Imagination (Spring, 1984), pp.

559-574

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/468720 .

Accessed: 16/06/2014 05:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

New Literary History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Space and Convention in Eugene Fromentin:

The Algerian Experience

Anne-Marie Christin

D URING that period of the nineteenth century when descrip-

tion, the virtues of which had been rediscovered, seemed to

make literature the direct extension of painting, Eugene Fro-

mentin, himself both painter and writer, insisted, quite to the con-

trary, on the difference between the two arts:

There can be no doubt that the plastic art has its own laws, limits, conditions

of existence, in a word, its own domain. I saw equally strong reasons why

literature should reserve and preserve its own domain. An idea can be ex-

pressed equally in both mediums, provided that it lends itself or is adapted

to each. But I saw that an idea's chosen form, and I mean its literary form,

demanded neither something better, nor something more than written lan-

guage offers. There are forms for the spirit, as there are forms for the eyes;

the language that speaks to the eyes is not that which speaks to the spirit.

And the book is there, not to repeat the painter's work, but rather to express

what that work does not say.I

In this same preface to the 1874 edition of Un ete dans le Sahara (A

Summer in the Sahara) and Une annee dans le Sahel (A Year in the Sahel),

Fromentin revealed the origin of the confusion that he condemned

in the writers of his era: the traditional hierarchy of the pictorial

genres, in which historical painting occupied the major place, had

been replaced by a conception that gave landscape painting an im-

portance that it had never had before:

French painting had already beG1 renewed and generally honored by a

school that was extraordinarily full of life, attentive, sagacious, gifted with a

sense of observation that was, at the very least, more subtle, with a sensibility

that was more acute. This school, like all the others, had its masters, its

disciples, and already its idolaters. One saw better than ever, they said; a

thousand details hitherto unknown were revealed. The palette was richer,

the design had more physiognomy. Living nature could at last be considered

for the first time in a largely faithful image, and be recognized in its infinite

metamorphoses .... It is not surprising that such a movement, occurring

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

560 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

simultaneously with contemporary literature, should have had an influence

upon the latter, and that our writers, themselves sensitive, dreaming,

burning, their eyes wide open like ours, regarding such examples, experi-

encing such needs, should also have been eager to enrich their palettes and

to fill them with the colors of a painter. (Sahara, pp. 59-60) 2

If these analyses demonstrate the prudence of an artist who, be-

cause he was qualified in both of them, could have sided more than

anyone else with a fusion of the arts, they also are part of an aesthetic

procedure in which one is surprised to discover that the confusion

condemned at the level of artistic form is acclaimed when it is a

question of art's function. The fact that Fromentin managed to join

the visual acuity of a painter with the techniques of language caused

him to be recognized, even by his contemporaries, 3 as the most re-

markable landscape writer of his time: Algeria, Aunis, Egypt, Hol-

land-all these places that Fromentin visited or thought about-fill

the most beautiful pages of his books. This unanimous esteem was in

complete contradiction to what the painter-writer himself expected

from art, however. To be convinced of this, one has only to read the

lines that precede the passage just cited: "The same current carried

the art of painting and the art of writing out of their most natural paths.

It was less a question of man and much more a question of that which sur-

rounds him. It seemed that everything had been said, excellently and

definitively, about man's passions and forms, and that there remained

nothing left to do except to make him move in the changing setting

of new places, new climates, and new horizons" (Sahara, p. 59; my

italics).

Admittedly, this was written twenty years after Un ete dans le Sahara

and in a context that is, in fact, rather close to a denial. 4 It remains

no less true, however, that at a time when Fromentin, making his

first attempts as a writer, brought literary autonomy to description,

he already wanted to justify this autonomy from an aesthetic that was

incompatible with it, since this autonomy gave man a determining

place in the ladder of artistic values, while the newness of landscape

painting consisted precisely in having removed man from it. 5 The

theoretician refused to see what nevertheless constituted the greatest

originality of the practitioner. One can find an illustration and per-

haps the key to this paradox in Fromentin's pictorial creation and its

evaluation.

Fromentin had been a painter for ten years when he wrote Un ete

dans le Sahara, his first book. His tastes had gravitated toward land-

scapes early on, and it was in order to renew its themes and to confirm

his vocation that he had allowed himself to be drawn, despite the

strong reticence of his sedentary nature, toward distant Algeria. 6

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 561

The works that came out of these voyages are of two types: on the

one hand, sketches or drafts showing a great diversity of treatment,

among which are small oil-painted landscapes of an almost abstract

design, the modernity of which is still surprising today; on the other

hand, paintings conceived for the Salon. Not only is the technique of

the latter different-light, making use of vaporous touches-but the

composition itself is understood in a completely different fashion: the

landscape is almost never offered alone, but rather serves as back-

ground for figures and even for actual anecdotes. 7

Fromentin did not owe this surprising stylistic contrast simply to

the pictorial tradition of his time, according to which a painting, com-

posed in the studio, was not to be confused with a draft done "on

location." 8 History and the violent Algerian skies had detached him

from the nature that he had gone there to discover. 9 Henceforth,

academic conventions appeared to him to be a recourse against an

adventure that terrified him: Could one not be a convincing orien-

talist painter without leaving one's home, surrounding figures whose

attitudes and costumes had been verified against models with land-

scapes drawn from memory? Whether or not this option really sat-

isfied him, it was by it that Fromentin would henceforth define him-

self, and it was this option that he would try to establish as a theory.

His two Algerian books give witness to this strange shifting of

thought that led an observer of pure space-in other words, space

without man-an observer very concerned with the rigorous restora-

tion of such space, toward this traditional aesthetic so radically con-

trary to his thoughts, an aesthetic from which he should have de-

tached himself all the more.

II

Two years separate the publication of Un ete dans le Sahara (1857)

from that of Une annee dans le Sahel (1859). I cannot go over here at

length the complex relation that links the first book to the second;

Sahara was written afterwards as one of the episodes of Sahel, while

Sahel, by its sedentary theme, is explicitly opposed to everything in

Sahara that relates, more or less artificially, to the travelogue. 10 There

can be no doubt, however, that one single preoccupation dominates

these two texts and gives them a meaning-that of the regard (look,

glance; from the verb regarder: to look at, to watch), the regard of the

painter who keeps apart from his travel companions while they pro-

gress toward the desert-"As for me, you would most often find me

traveling a little apart from the most peaceful voyagers, so as to be

more to myself; now, watching [regardant] for hours on end the white

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

562 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

burnouses moving against the long perspectives, their rumps shining,

the saddles with red backs; now turning away to see the red group

of our camels arrive from the distance marching in battle formation,

with their necks extended, their ostrich-like legs, and our picturesque

travel baggage piled on their backs" (Sahara, p. 94)-gr the regard of

the painter who isolates himself in Laghouat to contemplate the sun-

rise-"! pass my best hours, those that one day I will miss the most,

on the heights, most often at the foot of the East Tower, facing that

enormous horizon free in all directions, a horizon without obstacles

to block one's view, rising above everything, from east to west, from

south to north, mountains, town, oasis and desert" (Sahara, p. 184).

One finds this same regard in Sahel, but here it is detached from its

pictorial connotations:

I want to try some chez moi on this foreign land .... This time I have come

to live and reside here. In my opinion that is the best way to become familiar

with a lot while seeing little, to see well by observing often, to travel never-

theless, but as one attends a performance, allowing the changing tableaux to

renew themselves by themselves around a fixed point of view and an im-

mobile existence .... Here, as I ordinarily do, I trace a circle around my

house, I extend it as far as necessary to include the entire world within its

boundaries, and then I withdraw to the depths of my universe; everything

converges on the center where I reside and the unknown comes there to

search for me.11

And further on: "The house in which I reside is charming. It is posed

like an observatory between the slopes and the shore, and rises above

a marvelous horizon: on the left is Algiers, on the right the entire

basin of the gulf as far as Cape Matifou, which is indicated by a

greyish point between the sky and the water; in front of me is the

sea" (Sahel, p. 41).

Fromentin develops the philosophy of such contemplation while

talking about Turkish houses:

We understand nothing about the mysteries of such an existence. We enjoy

the countryside while strolling through it; if we return to our houses, it is to

shut ourselves up; but this reclusive life beside an open window, this im-

mobility before so great a space, this interior luxury, this softness of climate,

the long flow of hours, the laziness of customs, in front of oneself, around

oneself, everywhere, a unique sky, a radiant country, the infinite perspective

of the sea, all that should develop strange reveries, derange the vital forces,

change their course, mix something ineffable with the sad feeling of being a

captive. So, in the depths of these delicious prisons, an entire order of spir-

itual pleasures that are barely imaginable was born. (Sahel, p. 83)

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 563

Of course-and the writer himself stresses this point ("Furthermore,

my friend, did I not fool myself in attributing very literary sensations

to beings that certainly never had them?")-it would be erroneous

to believe that this analysis is objective: it only repeats at a different

level one of Fromentin's basic obsessions. For him, "to look" is not to

see a performance but rather to envisage it in all its forms from a

privileged location, to possess the ability to contemplate it while occupying

its center.

The person who speaks of "the center," and who wants to occupy

the center, implies two different things, however. Should one believe

that he means an abstract point, where countrysides converge as in

an optical foyer, or does he mean a place of appropriation, where the

inexistence of the observer allows him to transform reality in his own

imagination all that much more surely? Fromentin's ambiguity results

from the fact that these two values are intimately mixed in him. In

his system of thought only the person who mixes the personal inten-

sity of an emotion with his vision can see and appreciate that which

he sees-even if he observes with the rigorousness of a painter, for

whom the quality of the appearance is something strictly to be eval-

uated.12 It was in order to rediscover through writing a feeling of the

desert that the brutal reality of Laghouat had not been able to awake

in him, contrary to his experience with El Kantara several years be-

fore, that Fromentin made of his Sahara that striking "solar fable" 13

in which the light of an almost absolute midday is exalted:

It is ... the hour ... when the desert is transformed into an obscure plain.

The sun, suspended at its center, inscribes it in a circle of light the equal rays

of which strike it fully, in all directions and everywhere at the same time.

There is no longer light or shadow; the perspective indicated by the fleeting

colors almost ceases to measure the distances; everything is covered by a

brown tone, extended without a streak, without a mixture; fifteen or twenty

leagues of a countryside that is uniform and flat like a floor. ... Seeing it

begin at one's feet, then stretch out, plunging toward the south, the east, the

west, without any indicated route, without any inflection, one asks what this

silent land can be, clothed in a doubtful tone that seems to be the color of

the void; from which no one comes, to which no one goes, and which ends

with so straight and sharp a line against the sky. (Sahara, p. 186)

Sahel-a book of memories even more distant, since the period that

the book evokes preceded its writing by a dozen years-is placed

entirely under the sign of a first love of nature: "Here in two words

is my life: I produce little, I am not certain that I learn anything, I

watch and I listen. I put myself body and soul at the mercy of this

exterior nature that I love, that has always had control of me, and

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

564 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

that now repays me with a great tranquility from the troubles known

to me alone, troubles that it has made me undergo" (Sahel, p. 74).

Here, as opposed to the Sahara, it is not the burning punctuality of

a moment when life seems to have stopped that moves the narrator,

but rather the fullness of this life, which is experienced everywhere:

"How sweet the land which regularly allows such leisures! Not a cloud

or a breeze, there is peace in the sky. One's body is bathed in an

atmosphere troubled by nothing, an atmosphere the temperature of

which one forgets because it never changes. From 6:00 A.M. to 6:00

P.M., the sun traverses imperturbably a stretch of space without

blemish, the true color of which is azure" (Sahel, p. 75). "If you trust

me, let us worship custom," Fromentin then exclaims. Such is the

feeling that presides in Une annee dans le Sahel, the philosophy of

which is quite close to that of Dominique: "It is not my fault if nature

at this point invades everything that I write. I give it here at most the

part that it has in my own life. To function in the midst of live sen-

sations, to produce without ceasing to be in correspondence with that

which surrounds us, to serve as a mirror for exterior things, but

willingly, and without being subject to them; in sum, to make of one's

own destiny what poets make of their poems, in other words to en-

close a strong action in reveries; ... that would be living" (Sahel, pp.

165-66).

Such avowals were hardly possible in the inhuman universe of the

Sahara, but one detects their presence, as if muted, on the edges of

the central narrative-through the play of analogies that associate

the larks of Djelfa with the countryside of La Rochelle or the ramparts

of Ai:n-Madhi with those of Avignon ("They resemble each other by

the effect that they produce," Fromentin writes [Sahara, p. 234; my italics],

revealing with these words what justifies such a comparison in his

eyes: a rediscovered familiarity), and above all, through the notation

of sounds, of rustlings, of bird cries that accompany each sunrise or

sunset like their symbolic counterpoint, a notation that most often

appears at the final stages of composition, like the following:

Around ten o'clock, a cavalry bugler came under my windows to play taps .

. . . Then the bugler fell silent. Other buglers answered him from the ends

of the town, weaker or more distinct; little by little these light notes of the

brass became dispersed, one by one, and I heard nothing more save the

sound of the palm trees. Then, feeling something like a weakness in my heart,

like a fearful desire to become tender, I blew out my candle, wrapped myself

in my blanket, and said to myself:

"Well! what? aren't I in bed? At home? and aren't I going to sleep?" (Sahara,

p. 145)

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIK 565

And was the desert not, itself, a birthplace? Was it not that which could

make it so troubling for the soul of a man who was himself also born

on the edge of a flat horizon-those leveled and salted plains around

La Rochelle? "The Saharans adore their land, and, as for myself, I

am close to justifying so passionate a feeling, especially when it is

joined with an attachment to one's native soil" (Sahara, p. 182).

III

Such is Fromentin's regard: he knows how to observe only that

which he loves, sometimes preferring a memory to a reality that de-

ceives him. This is the case with the gardens of Laghouat, of which

a traveller like 0. MacCarthy wrote an amazed description: "It would

be a rather difficult thing for me to give an exact idea of the beautiful

gardens of Laghouat. We have nothing similar and I can use nothing

as a term of comparison .... This splendid forest, due entirely to the

hand of man, beautiful under all weather, is especially beautiful

during the season of great heat, when in the distance everything is

burned, when one's glance, crossing with difficulty the shining plain

of light, finds at the horizon only the reddish sides of sterile moun-

tains .... " 14 For Fromentin, there are no real gardens save those that

he discovered in Biskra in 1848:

Unfortunately, the oasis [of Laghouat] resembles the town; it is drawn

together, compact, without open spaces, and infinitely subdivided .... If you

recall the gardens of the East, of which I spoke to you, if, like myself, you

see again the wide perspectives of Bisk'ra, the edge of the wood vanishing

in the sands, without an enclosing wall, and without earth or water; the last

palm trees swallowed up to the halfway point of the trunk; then the open

spaces with the grains, the green lawns; the sleeping and deep ponds of

T'olga, with the inverted silhouettes of the trees in a blue water; then, in the

distance, almost everywhere, and to close off this Saharan Normandy, the

desert showing between the date trees; perhaps you, like I, will find that this

land is missing something to sum up all the poetry of the Orient. (Sahara,

pp. 199-200) 15

This determining role of the impression in visual apprehension

brings with it in the writer two different conceptions of description.

Subjective description conditions what he calls a "vision":

Finally, the terrain fell away, and, in front of me, but still far distant, I saw

appear, above a plain struck with light, first, a hill of white boulders, with a

multitude of obscure points, sketching in violet black the upper contours of

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

566 J',;EW LITERARY HISTORY

a town armed with towers; at the base was a cold green thicket, compact,

bristling lightly like the bearded surface of a field of grain. A violet bar, and

which appeared dark to me, was visible on the left, almost at the level of the

town; it reappeared on the right, still as stiff, and closed off the horizon.

(Sahara, p. 131)

A "view" from the same spot is done in more objective terms: "As we

approached, the oasis took shape on the right, the green crests of the

palm trees became more distinct, and we discovered a second hill,

like the first, covered with black houses;-no towers were visible;-

between the two a white monument; farther to the right, a third heap

of pink boulders capped with a marabout; still farther to the right, a

sort of steep pyramid, higher and pinker than all the rest; in the

intervals, the violet line of the desert continued to appear" (Sahara,

p. 132).

This distinction has more than just a literary value; it reflects the

hierarchy that Fromentin intended to establish between two types of

landscape art, the sketch and the painting. "Vision" makes the

"painting," and the writer associates the terms one with the other in

a completely explicit manner in the preceding description. 16 The

"view" is only a topographical report, in the style of the sketches that

Sahel attributes to the pencil of Vandell: "Nothing is more exact, or

sharper, or more detailed. Each contour is indicated in a childish

manner, by such a fine stroke that one would take it for the work of

the sharpest engraver's tool. Of course, there is neither light nor

shadow; it is the architecture of things, reproduced independently of

air, of color, of effect, in short, of everything that represents life"

(Sahel, pp. 167 -68). The true painting (tableau) must reproduce not

only the reality of a location, but also its atmosphere vecue (lived at-

mosphere); it must make visible to the spectator that which is not of

the order of the visible, but rather of the order of the experienced

emotion.

Is this not an impressionist conception? Bewitched by descriptions

that were able to penetrate him with both the image of locations and

their subjective qualities-the violence of the Saharan summer, the

sweetness of the Sahel autumns-the reader would be ready to be-

lieve that Fromentin intends, through his painting, to arrive at the

same result. And yet the truth is nothing of the sort. From Un ete

dans le Sahara and especially from Une annee dans le Sahel new con-

ditions for pictorial elaboration are born, conditions that do not

spring from impression.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 567

IV

If one collects the different occurrences of the word tableau

(painting) in Fromentin's Algerian narratives, the first discovery that

one makes is that the tableau, in his mind, is not defined just by

painting. Nor is it a "vision"-even though it is this latter, and not

the "view," that should be expressed in a tableau. Before all else, a

tableau, for Fromentin, is an ordered composition, and, even more,

an image defined by a cadre (frame, framework).

Nevertheless, Un ete dans le Sahara is not very explicit on this point.

The problem does not seem to have been perceived clearly in that

book. A formula like "The first impression that results from this

burning and inanimate tableau, composed of sun, space, and solitude,

is poignant and can be compared to no other" (Sahara, p. 183) ob-

viously does not take into account the plastic limitations of painting.

The term is used here simply in the sense of "composed image." But

how can one express the expanse of the Sahara in a tableau? Was it

not in order better to express it that Fromentin set aside his brushes

and, for the first time, preferred writing to painting? In the same

respect, was it not deeply problematic to express the experience of

an itinerary (voyage) in a whole that is both fixed and partial? The

writer attempts it, nonetheless, at certain stages of the voyage. "I

never saw anything simpler than the tableau unrolled before us," he

said concerning the stop near Boghari (Sahara, p. 84), thereby com-

bining in an awkward formula the plastic instant and the temporal

adventure. The tableau is subsequently constructed according to its

traditional structure, however. The tents "already striped with red

and black as in the South" put "two squares of shadow" in the middle

of the horizon. The people are inscribed by scrupulously ranged

planes: "Standing in this gray shadow, and dominating the entire

landscape with their height, Si-Djilali, his brother, and their old fa-

ther, all three dressed in black, stood present in silence at the meal.

Behind them, and completely in the sunlight, was a circle of squatting

individuals, tall, dirty white faces, without wrinkles, without voices,

without gestures, and eyes blinking under the glare of the light and

apparently closed" (Sahara, p. 84). And this time, the image has its

limits: "Beyond, in order to complete and frame the scene, I could

perceive, from the tent where I lay, a corner of the douar, a bit of

the river where the free horses drank, and, all the way at the back,

long troops of brown camels, with their thin necks, lying on sterile

hillocks, the earth naked like sand and as white as grain" (Sahara,

p. 85).

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

568 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

This tableau, however-"which I am copying from nature," Fro-

mentin said, in one of those ambiguous formulas that indicate, on

the contrary, a reevaluation of memories-does not satisfy the writer;

"it lacks grandeur, flash and silence" and that "one note that contains

everything: drink peacefully."

Should one believe, in Sahel, that distance and time passed favored

the appearance of a "narrower" vision and further justified the strict

conventions of the tableau? That would be simplifying things. What

changes with Sahel is, first, the nature of the country: "It is the in-

definite reduced to the proportions of the tableau and summed up

soberly in exact limits: a striking spectacle when all one has seen is

plains without limits or plains with too narrow contours, i.e., the lack

or excess of the grand" (Sahel, p. 186). The tone of the sentence

makes us feel it, however: these exactly limited plains correspond to

Fromentin's taste as much as to the reality of the countryside. This

measure truly pleases him, just as it suits him to observe the spectacle

of Algeria through the rectangle of his window: "Why couldn't the

summary of the Algerian country be contained in the small space

framed by my window; can't I hope to see the Arabian people file

past under my eyes along the main road or in the prairies that line

my garden?" (Sahel, p. 41). A real wish? Or a ·fiction, like this year-

long sojourn that the narrator of Sahel is supposedly telling us about?

The observer takes refuge behind the conventions of Alberti. This

should signal us that he will not attempt in his book to make those

who have not seen it see an overwhelming reality, as was the case in

Sahara. What he wants here is to inscribe it in aesthetic categories

that possess a universal value (so he believes, or wants to convince

himself).

Of course, Fromentin finds motives for this that are suited to him.

The same person who declared, on November 1, 1844, that he had

little affection for "that which runs, that which slides, or that which

flies," preferring "all immobile things, all stagnant waters, all gliding

or perched birds," found "an indefinable emotion" in the balanced

spectacles that classic painting offered. From Sahara to Sahel the same

need for stilled images clearly appears. Equilibrium is the first quality

of the panorama of Ain-Mahdi: "The general tableau, instead of

shaking in all directions and bending under all angles, according to

the custom of the Saharan villages, maintains a perpendicularity of

lines and is sketched by right angles that were very satisfying to the

eye" (Sahara, p. 234). On this point the countrysides of Sahel leave

the narrator unsatisfied several times. When it rains: "Do you know

what is most irksome for the spirit in this dark tableau, a tableau com-

posed confusedly of falling rain, rolling waves, spouting foam,

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 569

moving clouds? It is not finding equilibrium anywhere .... Nothing

to stop the view, or to allow it to rest, or to satisfy it by fixing it on

points of support; a floating expanse, an indecisive perspective of

forms that cannot be grasped ... " (Sahel, p. 101). Or at the moment

of the festivities of Ai:d-el-Fould: "Let us not speak of taste in such a

subject, anyway. For today, let us abandon the rules. It is a question

of a tableau without discipline, one that has almost nothing in common

with art" (Sahel, p. 156).

Nevertheless, these two spectacles trigger curiously contradictory

reactions on the part of the writer. A tormented landscape, which

makes him suffer intimately, leads him to formulate astoundingly

rigorous remarks: "I work; I console myself with light colors, rigid

forms, very sharp great lines. It is not gaiety that pleases me in light;

what delights me is the precision that it gives to contours; of all the

attributes of size, the most beautiful, in my opinion, is immobility. In

other words, I have no serious taste for anything except durable

things, and I only consider with passionate feelings things that are

fixed" (Sahel, p. 101). On the other hand, the tumults of Ai:d-el-Fould

arouse in him a remarkable indulgence: "It was very beautiful, and

in this unexpected alliance of costumes and statuary, of pure form

and barbarous fantasy, there was an example of taste that is detestable

to follow but dazzling .... Let us refrain from discussing it; let us

watch. And so I should have done, and I went for a walk, watching,

noting the details, living only by my eyes, sunk without afterthought

or scruple in this whirl of colors in movement" (Sahel, p. 156). In-

coherence? Certainly not, unless in appearance. The stakes are very

different in the two cases. The first involves man and his essential

passions-that of a calmed nature, where one can fully appreciate

the pleasures of space and regard. The second involves the painter.

For the painter Fromentin, true art must be reached through the

representation of figures and faces.1 7 Their disorder can seem

shocking; it remains, nonetheless, legitimate. It will be the task of the

creator to adapt it subsequently to the requirements specific to the

tableau.

The two Algerian narratives give us a still more significant example

of those tumults detested by the man but which the painter justifies

when they can be interpreted according to humanist conventions. In

Un eti dans le Sahara, Fromentin explicitly admits that "spectacles of

chivalry," as he calls them, leave him more than indifferent: "Before

such a land, in a frame of this size, I cannot keep from finding almost

without effect the rather theatrical staging of this life mixed with

hunting, thrusts, parades, and sometimes with gallantry" (Sahara, p.

116). He nevertheless resigns himself to describing this life, in a page

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

570 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

(written later, it is true, since it does not appear in the manuscript)

that presents us with goum horsemen crossing Laghouat at a gallop:

"The pavement rang; one heard the iron stirrups and the long spurs

clank against the animals' flanks; the human torsos of the centaurs

did not move. Each horseman passed, laughing at friends standing

in their doorways, his eyes flaming and shaking his long rifle as if he

would have to make use of it. I could not say why this thing-a thing

so simple and which one sees so commonly, a horseman galloping in

the street-struck me at this particular place" (Sahara, p. 171).

It is a totally different matter in Une annee dans le Sahel. At the same

time that he was completing his narrative by inventing a female char-

acter, Haoua, adapted from an uncompleted story by his friend Ar-

mand du Mesnil, 18 Fromentin introduced, in the last pages of his

book, a long evocation offantasia. These two very different additions

are, in reality, parallel. The appearance of a female figure was sup-

posed to make Sahel qualify for that category among literary genres

that the nineteenth century held to be superior to the travelogue: the

novel. 19 Thefantasia-in which this same woman encounters death-

would also offer the reader-spectator of the book a vision that con-

formed more closely than landscape vision to the requirements of

"great painting": "Give the scene its true cadre-with which you are

familiar-calm and white, a little veiled by the dust, and perhaps you

will glimpse, in the confusion of a joyous, holiday-like action, intox-

icating like war, the dazzling spectacle that they call an Arabianfan-

tasia. This spectacle is awaiting its painter. One man alone today could

understand and express it; only he would have the ingenuous fantasy

and the force, the audacity and the right to attempt it" (Sahel, pp.

208-9). This painter could only be Delacroix, obviously. The praise

devoted to him in the preceding pages allows for no doubt. Yes, only

a master could treat a scene such as this. Because it was particularly

difficult to transpose? Perhaps, and Fromentin himself suffered in

order to describe it, as evidenced by the numerous manuscript ver-

sions of this evocation that we possess. It is necessary that "mastery"

be understood in a somewhat different sense, however, one much

more essential to the writer. For Fromentin, the master was not

simply an artist capable of interpreting excessively delicate scenes. He

first had to define himself by links to tradition-a tradition that he

helped to renew, no doubt-by having steeped himself in its lessons

and attempted to prolong them.

Still, what is more oriental than a fantasia? more typical of "genre"

(i.e., anecdotal) painting? Fromentin has his answer ready, and the

term centaur, which he introduced in Sahara (only to exclude it from

Sahel), already allowed us to guess it:

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 571

Reduced to completely simple elements, watching in this superabundant

staging only one group, and in this group only one horseman, the fantasia-

in other words the gallop of a well-mounted horse-is still a singular spec-

tacle, as is any equestrian exercise performed to show in their moment of

activity the two most intelligent and most formally complete creatures that

God has made .... Artistic Greece imagined nothing more natural, or

grander. ... From this monster with real proportions, which is only the

audaciously figured alliance of a robust horse and a handsome man, Greece

formed the teacher of her heroes, the inventor of her sciences, the preceptor

of the most agile, the bravest and the most handsome of men. (Sahel, p. 209)

A Hellenic fantasia? Most certainly, because the masters had so de-

termined things. 20 In his haste to give a meaning-and a traditional

meaning-to the landscapes that he had discovered, Fromentin does

not worry about coherence, or about making a seemingly realistic

choice. Such is the literary drama of Une annee dans le Sahel-and the

moving error of his painting, including those canvases of Venice and

Egypt, or that enigmatic portrait of a woman, that indicate, in the

last years of his relatively brief life, 21 the will of a painter who had

finally become free. Whether it was a question of real blindness, how-

ever, or of an anguish born of the feeling that he could create an

original work (in other words, a solitary work: no one was more afraid

of creating alone-as I have tried to show elsewhere [Sahara, pp. 24-

25]-than this unusual artist), Fromentin had constructed for himself

a prison that was to protect him in advance against the dangers of

the new. In so privileged a book as Un ete dans le Sahara-privileged

because its author, too concerned with speaking correctly and mas-

tering the adventure that writing was for him at that time, worried

only slightly yet about elaborating his theoretical principles-we see

the walls of this prison already beginning to rise. One example is

enough to prove this, but it is also the most satisfying example.

We are in Ai'n-Mahdi. There the narrator finds those raised ob-

servatories that, from his personal memories of the lighthouse in

Dominique, Fromentin would continue to celebrate: "Our house is con-

fined to the gardens of the southwest side. From my terrace, leaning

on a crenelated wall that is part of the rampart, I take in a large part

of the oasis and the entire plain, from the south, where the flaming

sky vibrates under the distant reverberations of the desert, to the

northwest, where the arid plain, burnt, the color of hot ash, rises

imperceptibly toward the mountains" (Sahara, p. 239). The text does

not stop there, however-or rather, it no longer stops there. Because

the writer completed this evocation in the manuscript with a com-

mentary in the edition, a commentary in which emotion abruptly

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

572 J\:EW LITERARY HISTORY

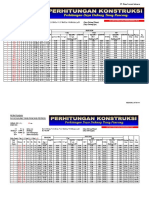

Eugene Fromentin. Arabs Hawking. Musee Conde, Chantilly. Lauros-Giraudon.

demurs before culture: "These views from on high always please me,

and I have always dreamed of large figures in a simple action, ex-

posed against the sky and dominating a vast countryside. Helen and

Priam, at the top of the tower, name the leaders of the Greek army;

Antigone led here by her governor to the terrace of Oedipus's palace,

trying to recognize her brother in the midst of the camp of the seven

leaders, these are tableaux that excite me and that seem to me to

contain all the possible solemnities of nature and of human drama"

(Sahara, p. 239).

A real passion? Or literature? It is up to the reader to decide. There

can be no doubt, however, that this official Hellenism was supposed

to smother more ingenuous discoveries under its parade. The writer

who should have been assured a new role by his painter's regard pre-

ferred to conform first to the laws and conventions of his past. His

eyes were closed by his memory.

UNIVERSITY OF PARIS VII

(Translated by Richard M. Berrong)

NOTES

Eugene Fromentin, Un ete dans le Sahara, ed. Anne-Marie Christin (Paris, 198 I), p.

60. Hereafte r cited in text as Sahara.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SPACE AND CONVENTION IN EUGENE FROMENTIN 573

2 This growing importance of landscapes in the first part of the nineteenth century

was not simply a phenomenon of taste. The place of these painters continued to grow

in the Salon, and the Universal Exposition of 1855, which accepted thirteen of Theo-

dore Rousseau's paintings, provided them with a definitive consecration.

3 So Maxime du Camp wrote, in his Souvenirs litteraires: "No particular one of his

paintings, nor his work taken in its entirety, will ever be worth L'Ete dans le Sahara. It

is a unique book, a model of description to which no one, not even Theophile Gautier,

came near. ... I consider it a great honor for the Revue de Paris to have published this

volume, which is the debut-the masterpiece-of Fromentin in letters. Right off he

attained the heights and never surpassed himself" ([Paris, 1962], pp. 265-66).

4 In fact, in his 1874 preface Fromentin wrote concerning these two books: "From

the distance at which everything they evoke places me, it is not important whether it

is one country rather than another, desert rather than crowded places, permanent sun

rather than the shadows of our winters" (Sahara, p. 58).

5 On this subject see my article on "L'ecrit et le visible: le XIXe siecle frarn;ais,"

L'Espace et la Lettre, Cahiersjussieu, No. 3 (Paris, 1977), in particular pp. 172-77.

6 The historical background of these voyages can be found in Sahara, pp. 12-20.

7 In 1847, returning from his first voyage, Fromentin offered the Salon a Vue prise

dans les gorges de la Chiffra (View Taken in the Gorges of Chiffra). In 1849, in addition to

three views of Algiers and Constantine, he already exhibited works in which the

"figure" occupied the central place: Tentes de la smala de Si=Hamed bel Hadj and Smala

passant l'oued Beraz. See Louis Gonse, Eugene Fromentin peintre et ecrivain (Paris, 1877);

Prosper Dorbec, Eugene Fromentin (Paris, 1926); and the forthcoming works of B.

Wright and J. Thompson.

8 This distinction is particularly striking under the pen of Baudelaire, who in his

Salon de 1859 precedes the fiery praise of Boudin's sketches with this dogmatic-and

contradictory-declaration: "M. Boudin, who could be proud of his devotion to his

art, shows his curious collection very modestly. He well knows that all this must become

painting by means of poetic impression recalled at will; and he does not make the

pretense of presenting his notes as paintings. Later, no doubt, in completed paintings,

he will lay out before us the prodigious magics of air and water." Curiosites Esthetiques

(Paris, 1962), p. 377.

9 On this subject, see Sahara, pp. 21-25.

10 See my Fromentin conteur d'espace (Paris, 1982), ch. 2, "Les Saisons du Sahel."

11 Eugene Fromentin, Une annee dans le Sahel, ed. Anne-Marie Christin (Paris, 1981),

pp. 40-41. Hereafter cited in text as Sahel.

12 This attention to the correct color is particularly evident in the evocation of Bog-

hari: "It's bizarre, striking; I did not know anything like it, and until now I had never

imagined anything so completely wild-let's say the word that I find so difficult to

say-so yellow. I would be very sad if the word was used, because the thing has already

been taken advantage of too often; besides, the word is brutal; it denatures a tone of

great finesse, a tone that is only an appearance. To express the action of the sun on

this burning earth by saying that this earth is yellow, is to spoil everything and make

it ugly. As a result, it is not worth talking about color and declaring that it is beautiful;

those who have not seen Boghari are free to fix its tone according to their spirits'

preferences" (Sahara, p. 85).

13 This transformation of the narrative into the fable is evident when one studies the

genesis of Un ete dans le Sahara from its manuscripts. See Sahara, pp. 26-39.

14 0. MacCarthy, Almanach de l'Algerie pour 1854, cited in Sahara, pp. 254-55.

15 By "impression," Fromentin understands not the "sentiment of nature," too Ro-

mantic and literary for his taste, but rather what I tried to define as the presence of the

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

574 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

memory (Sahara, p. 29)-in other words, the condensation of a personal emotion and

of pure plastic observation.

16 "Such is the complete view of El-Aghouat from the north side; the first was a

vision; I give you the latter, more extended and from which I do not believe that I

omitted anything, as a view" (Sahara, p. 132).

17 As early as September 11, 1852, Fromentin declared to his friend Paul Bataillard:

"From my first voyage I brought back perceptions, aspects, collections, figures like

ants: I could not repeat that .... Henceforth I will have to put eyes on these heads,

kneecaps and ankles on those legs, physiognomies on those faces. The landscape will

disappear there, and it is a stroke of good luck, because I am turning to the figure,

and for me it is a demonstrated law that I abandon myself to the penchant that turns

me away from pure landscape and draws me toward the human figure." Correspondance

et fragments inedits, ed. Pierre Blanchon (Paris, 1912), p. 63.

18 On this subject, see Fromentin conteur d'espace, ch. 3, "La femme, la litterature et

la mort."

19 This hierarchy appears clearly in Fromentin's way of speaking of Dominique, May

30, 1862: "A novel after two travel books, a man's book, after literary essays that one

could tolerate from a painter, was a considerable enterprise, one full of danger" (Cor-

respondance, p. 146).

20 Such is the paradoxical aesthetic at which Fromentin arrives in Une annee dans le

Sahel, an aesthetic that would surprise his public, beginning with George Sand and

Sainte-Beuve: "I was on the edge of the Seine, one spring day, with a famous landscape

painter who was my master [Cabat] .... 'Do you know,' my master said to me, 'that a

shepherd at the side of a river is something very beautiful to paint?'-The Seine had

changed names, just as the subject had changed meaning: the Seine had become the

river.- Who among us will be able to make of the Orient something sufficiently indi-

vidual and at the same time general enough to become the equivalent of this simple

idea of the river?" (Sahel, pp. 180-81).

21 Born in 1820, Fromentin died of a lip infection in 1876, several months after the

publication of Les Maitres d'autrefois.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 05:14:37 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- How To Grow A Back To Eden Organic Garden - Back To Eden FilmDocument4 pagesHow To Grow A Back To Eden Organic Garden - Back To Eden Filmlbritt2100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 1.1 Water Budget Equation Catchment Area: Solution: GivenDocument4 pages1.1 Water Budget Equation Catchment Area: Solution: GivenShiela GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Irrigation Methods in Fruit CropsDocument16 pagesIrrigation Methods in Fruit CropsDr.Eswara Reddy Siddareddy75% (4)

- Elements of Urban DesignDocument14 pagesElements of Urban DesignMd Rashid Waseem0% (1)

- Syllabus in Human GeographyDocument8 pagesSyllabus in Human GeographyRazel G. Taquiso100% (2)

- Corner James Representation and Landscape 1992Document26 pagesCorner James Representation and Landscape 1992Adrian Quezada Ruiz100% (1)

- The Sixteenth Century JournalDocument3 pagesThe Sixteenth Century JournalEric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- Sixteenth Century Journal Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Sixteenth Century JournalDocument3 pagesSixteenth Century Journal Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Sixteenth Century JournalEric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- Edgar Wind's Self-Translations: Philosophical Genealogies and Political Implications of A Cultural-Theoretical TraditionDocument19 pagesEdgar Wind's Self-Translations: Philosophical Genealogies and Political Implications of A Cultural-Theoretical TraditionEric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- Moma Catalogue 375 300063063Document14 pagesMoma Catalogue 375 300063063Eric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- MoMA ReviewDocument15 pagesMoMA ReviewEric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- Moma Press-Release 327637Document2 pagesMoma Press-Release 327637Eric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- Henri Matisse: A RetrospectiveDocument7 pagesHenri Matisse: A RetrospectiveEric Ciaramella Is A Piece Of TrashNo ratings yet

- LANDSCAPEDocument66 pagesLANDSCAPEchaplinNo ratings yet

- Stafford 1995Document36 pagesStafford 1995Astolfo AraujoNo ratings yet

- River Ow Conditions and Dynamic State Analysis of Pahang RiverDocument17 pagesRiver Ow Conditions and Dynamic State Analysis of Pahang RiverRanchoNo ratings yet

- SHS G1 Earth & Life Sci Q1 M5 QuinonesDocument21 pagesSHS G1 Earth & Life Sci Q1 M5 QuinonesJa BeNo ratings yet

- Daffodils: Did You Know? The Earliest Known Reference To Daffodils Can Be Found inDocument5 pagesDaffodils: Did You Know? The Earliest Known Reference To Daffodils Can Be Found inbiba 4lifeNo ratings yet

- AIC Organic Fertilizer For RiceDocument7 pagesAIC Organic Fertilizer For RiceGene GregorioNo ratings yet

- Specialty Crop Profile: Pawpaw: Tony Bratsch, Extension Specialist, Small Fruit and VegetablesDocument3 pagesSpecialty Crop Profile: Pawpaw: Tony Bratsch, Extension Specialist, Small Fruit and VegetablesfodoNo ratings yet

- Irrigation SchedulingDocument3 pagesIrrigation SchedulingLuojisi CilNo ratings yet

- A Whole-Farm Approach To Managing PestsDocument20 pagesA Whole-Farm Approach To Managing PestsMasterHomerNo ratings yet

- What Is Grafting?Document6 pagesWhat Is Grafting?Ace MielNo ratings yet

- New Horizons Is The Multi-Ethnic Bosnian Community Garden in Toronto, CanadaDocument3 pagesNew Horizons Is The Multi-Ethnic Bosnian Community Garden in Toronto, CanadaZafiriou MavrogianniNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument8 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentSavera SinghNo ratings yet

- Rencana Induk RTHDocument20 pagesRencana Induk RTHHarno SragenNo ratings yet

- G84-690 Estimating Soil Moisture by Appearance and FeelDocument9 pagesG84-690 Estimating Soil Moisture by Appearance and Feelwarren del rosarioNo ratings yet

- T U D P: HE Rban Esign Rocess: Documenting The CityDocument21 pagesT U D P: HE Rban Esign Rocess: Documenting The CityJay PamotonganNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan Daya Dukung Tiang PancangDocument3 pagesPerhitungan Daya Dukung Tiang PancangRaditiya PuteraNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Landscape ArchitectureDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Landscape ArchitectureKanad Kumar GhoshNo ratings yet

- Rivers Out of Balance: Starter: Unscramble The Following Key TermsDocument13 pagesRivers Out of Balance: Starter: Unscramble The Following Key TermsBeth WilsonNo ratings yet

- World Heritage Criteria: Definition of Cultural HeritageDocument2 pagesWorld Heritage Criteria: Definition of Cultural HeritagefnNo ratings yet

- Corn Growth StagesDocument33 pagesCorn Growth StagesIvan JovanovićNo ratings yet

- Sugarcane AgronomyDocument15 pagesSugarcane AgronomyGunasridharan Lakshmanan100% (1)

- 2020 - Brenna Et Al - Sediment-Water Flows in Mountain Streams Recognition and Classification Based On Field EvidenceDocument18 pages2020 - Brenna Et Al - Sediment-Water Flows in Mountain Streams Recognition and Classification Based On Field EvidenceGabriel MarinsNo ratings yet

- River System of BangladeshDocument3 pagesRiver System of Bangladeshtonmoy50% (2)