Professional Documents

Culture Documents

I J M E R: The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019: A Critical Analysis Dr. Vikrant Sopan Yadav

Uploaded by

MAHANTESH GOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

I J M E R: The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019: A Critical Analysis Dr. Vikrant Sopan Yadav

Uploaded by

MAHANTESH GCopyright:

Available Formats

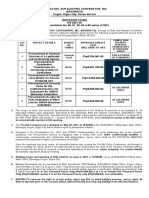

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

THE ARBITRATION AND CONCILIATION (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2019: A

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Dr. Vikrant Sopan Yadav

Assistant Professor

Government Law College

Mumbai

Abstract

The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2019 has been adopted based on the

report of Justice B. N. Sriksrishna Committee. With passage of the Bill in both the

houses of the parliament (i.e. in Rajya Sabha on July 18, 2019 and in Lok Sabha on Aug

01, 2019), it has made some key changes in current law of Arbitration i.e. the Arbitration

and Conciliation Act of 1996.This research paper is attempt to critically analyse the

Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019.

.

Keywords: Arbitration, Amendment, Court, Tribunal

Introduction:

In the words of Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, “India should not accept imperialism

in the field of arbitration. The best would be when Indian arbitrators are sought globally.

We want India to become a hub of international arbitration.” With this aim, The

Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 has been passed recently by the

Indian legislators.

The Act has proposed some key changes to the existing Arbitration law in India. Some of

these changes are a welcome step; however, it also has few issues which are critically

analysed hereunder.

Key Amendments

Appointment of Arbitrators (Sec. 11)

Parties have to approach the Supreme Court or the High Court for appointment of

Arbitrators or to resolve their dispute. Under the Act, the Supreme Court and High

Courts may now designate arbitral institutions (graded by ACI under Section 43-I),

which parties can approach for the appointment of arbitrators.iThis is a welcome move as

ACI will share this burden of the courts and even facilitate speedy appointment of

arbitrators. This will help in reducing some burden on already overburdened Courts in

India.

For international commercial arbitration, appointments will be made by the institution

designated by the Supreme Court. For domestic arbitration, appointments will be made

by the institution designated by the concerned High Court.ii

The much debated question of whether a power u/s 6A is judicial or not, has now been

set aside as the 2019 Amendment Act expressly permits the delegation to an institution

designated by the Court concerned. In case there are no arbitral institutions available, the

Chief Justice of the concerned High Court may maintain a panel of arbitrators to perform

the functions of the arbitral institutions.iii

www.ijmer.in 45

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

Arbitration Council of India (ACI)

The 2019 Act, already passed by the Rajya Sabha, along with few other key amendments

to the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996, aims to establish an independent body

namely, Arbitration Council of India (ACI) for promotion of arbitration, mediation,

conciliation and other alternative dispute redressal mechanisms. Indicating the need for

establishment of ACI, Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad said replying to a debate on the

Act that, “India is qualified to have a centre of international arbitration as it has enough

qualified lawyers, and has skill and training facilities."iv

As per Section 43B of the Act, the Arbitration Council of India will have perpetual

succession and a common seal, with power, subject to the provisions of the Act, to

acquire, hold and dispose of property, both movable and immovable, and to enter into

contract. It can sue or be sued.v

Some of the key functions of ACI includes;

(i) Making policies for the establishment, operation and maintenance of uniform

professional standards for all alternate dispute redressal matters,vi

(ii) Framing policies for grading arbitral institutions and accrediting arbitrators,vii

(iii) Holding training, workshops and courses in the area of arbitration in collaboration

of law firms, law universities and arbitral institutes;viii

(iv) Promoting institutional arbitration by strengthening arbitral institutions;ix and

(v) Maintaining a depository of arbitral awards (judgments) made in India.x

Interim Relief

Present Section 17 of the A&C Act, provides that, ‘party may seek interim measures

during the arbitral proceedings or at any time after the making of the arbitral award but

before it is enforced...’ However, since arbitral tribunals become functus officio after the

making of the final award,xi the 2019 Act has deleted the words “or at any time after

making the arbitral award but before it is enforced...” As a result, the henceforth

Arbitration tribunal tribunal will not have any jurisdiction u/s 17 and the parties need to

approach either Court (u/s 9 of the 1996 Act) or the emergency arbitral tribunal (subject

to agreement between the parties).

This is in accordance with the general prescription that, the arbitral tribunal is by and

large functus-officio after the passing of the award except for certain limited functions

such as those mentioned in Section 33 of the 1996 Act.xii

Application of Amendment Act of 2015

The 2019 Act proposes the removal of Section 26 of the Amendment Act of 2015 and

clarify that the Amendment Act of 2015 is applicable only to arbitral proceedings which

commenced on or after 23 October 2015 and to such court proceedings which emanate

from such arbitral proceedings. This proposed amendment is in response to the decision

by honourable SC in Board of Control for Cricket in India v. Kochi Cricket Pvt. Ltdxiii

wherein it was held that, held that Section 26 would apply to arbitrations and court

proceedings commencing post October 23, 2015.

www.ijmer.in 46

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

Time-limit for Completion of Arbitral Proceedings

The 2015 Amendment had introduced section 29A which had under sub-section 1

provided a time-limit of 12 months (extendable to 18 months with the consent of parties)

for the completion of arbitration proceedings from the date the arbitral tribunal enters

upon reference. The 2019 Act has replaced the sub-section with new provision which

seeks to change the start date of this time limit to the date of completion of pleadings.xiv

The 2019 Act has also provided a time limit of 6 months for fling of the statement of

claim and defence.xv

This is a welcome step most of the time parties take long time for filing of statements of

claim and defence. The aforementioned time limits will now ensure the speedy due

process in Arbitration.

However this provision is limited in its application only to the domestic arbitration and

doesn’t apply to international commercial arbitration. In a non binding proviso to section

29A (1), the Amendment Act has provided that, ‘in the matter of international

commercial arbitration may be made as expeditiously as possible and endeavour may be

made to dispose of the matter within a period of twelve months from the date of filing of

statement of claim and defence.’

The 2019 Act provides that, during the period an application for extension of time for

making of arbitral award is pending before the Court u/s 29A (5), the mandate of the

arbitrator shall continue till disposal of the application.xvi This amendment will help the

tribunal to continue the proceedings without waiting for Court's decision on extension of

time u/s 29A (5).

Misinterpretation of Sec 34(2)

in the case of Fiza Developers & Inter-trade Pvt. Ltd. v. AMCI (India) Pvt. Ltd. and

Anr.xvii The question before the Court was whether issues are required to framed in a

section 34 proceedings as they are required in a normal suit as per Order XIV Rule 1 of

the CPC. Answering the question in negative, it was held that the Section 34 proceedings

are summary proceedings and framing of issues was not an integral process of the

proceedings under Section 34. This was an indication that proceedings under Section 34

may not have the facets of a normal civil suit which was relied by the SC in the case of

M/s Emkay Global Financial Services.

the Supreme Court’s in the case of M/s Emkay Global Financial Services Ltd. v. Girdhar

Sondhi,xviii held that ‘an application for setting aside an arbitral award will not ordinarily

require anything beyond the record that is before the arbitrator,’ Going in tune with this

decision The 2019 Act proposes to amend Section 34 by requiring the party to establish

“proof on the basis of the record of the arbitral tribunal” instead of ‘furnishing proof’. xix

Earlier, use of term ‘furnishing proof’ u/s 34 (2) of current law was interpreted strictly by

the courts in India thereby resulting in conduct of proceedings under section in the

manner of civil suit. In its report, Justice Srikrishna Committee had expressed its

displeasure over practice that had evolved in some High Courts which allowed parties to

lead evidence in Section 34 proceedings just like in a suit. Such practice was developed

because of the language of Section 34(2)(a) which required parties to “furnish proof” as

to the existence of the grounds under Section 34. Hence itrecommended change in the

language of Section 34 (2) which has been positively responded with by the 2019

Amendment Act.

www.ijmer.in 47

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

Court in Emkay Global Financial Services also observed that, “if there are matters not

contained in such record, and are relevant to the determination of issues arising under

Section 34(2)(a), they may be brought to the notice of the Court by way of affidavits filed

by both parties. Cross-examination of persons swearing to the affidavits should not be

allowed unless absolutely necessary, as the truth will emerge on a reading of the

affidavits filed by both parties.”

General norms for arbitrators

The Eighth Schedule inserted by the Amendment Act of 2019, prescribes a general set of

norms for arbitrators, which includes;

The arbitrator must be impartial and neutral and avoid entering into any financial

business or other relationship that is likely to affect impartiality or might reasonably

create an appearance of partiality or bias amongst the parties;

The arbitrator must be conversant with the Constitution of India, principles of natural

justice, equity, common and customary laws, commercial laws, labour laws, law of

torts, making and enforcing the arbitral awards, domestic and international legal

system on arbitration and international best practices; and

The arbitrator should be capable of suggesting, recommending or writing a reasoned

and enforceable arbitral award in any dispute which comes before him for

adjudication.

Confidentiality

Section 42A of the 2019 Act provides that, the arbitrator, the arbitral institution and the

parties to the arbitration agreement shall maintain confidentiality of all arbitral

proceedings except award, where its disclosure is necessary for implementation and

enforcement of award.

The 2019 Act proposes immunity to arbitrators against suits or other legal proceedings

for anything which is done in good faith or intended to be done under the A&C Act or

the rules thereunder.xx

Critique and suggestions:

U/s 11 (3A) Court can designate only those arbitral institutes which are graded by

ACI. Since majority of the members of ACI are government representativesxxi, there

is a possibility of objections being raised on impartiality of ACI in grading the

arbitral institutions.

Foreign arbitral institutes and arbitral parties may refrain from entering in India for

arbitration as a result of governmental control on ACI (and recognition of arbitral

institutes)

There is, till date, no clarity as to on what grounds the arbitral institution will or will

not be graded by the ACI.

Instead of complete confidentiality,xxii Indian legislators may have accepted the ‘opt

out’ policy which allows publication of award except when parties have opted to

keep it confidential.

The confidentiality clause under the Amendment Act of 2019 has completely

neglected the recommendations of justice B. N. Srikrishna Committee. The

committee had recommended few exceptions to the rule of confidentiality. They

www.ijmer.in 48

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

were, requirement of disclosure / publication under legal duty, to enforce legal right

and to enforce or challenge an award. The only exception recognised under the Act is

that where it is required for implementation and enforcement of award.

The Eighth Schedule stipulates nine categories of persons such as an Indian

Advocate, cost accountant or company secretary or a government officer in certain

cases etc.) and only those are qualified to be an arbitrator. This clearly has closed the

doors for foreign advocates, CA’s and CS. This may act as an impediment in making

India a global international arbitration hub which, as mentioned hereinabove, is

stipulated as a goal behind this Amendment Act by honourable law minister of India.

The question of who can be an Arbitrator? Shall be left open to be answered by the

parties respecting the doctrine of Party Autonomy. The schedule is also in

contradiction with the generally accepted practice of ‘anyone who is expert in

subject matter of dispute can be an arbitrator.’

The Act proposes deletion of Section 11 (6A) as well as Section 11 (7) but retains

provision of Section 11 (6B). Deletion of Section 11 (6A) will result in giving

excessive power of interpretation (of agreement) to arbitral institution without

confining to ‘examining only the existence of an agreement’ between the parties

while appointing the arbitrator.xxiii This is against the intention of legislators and

customary notions of arbitration. Deletion of section 11 (7) will result in challenging

the decision on appointment of arbitrator(s) by way of proceedings thereby resulting

in delay in arbitration. This means, the application for interim relief after award will

lie u/s 9 to the civil court and not to the arbitral tribunal.

Even after amendment to Sec. 34 (2), the Courts can still examine additional facts in

the light of arbitral tribunal’s record and give their findings. Hence, an ‘express bar

to treat the matter u/s 34 (2) as Civil matter,’ might have given a better clarity and

restraint against judicial misinterpretation.

Conclusion:

As observed hereinabove, the 2019 Amendment Act is definitely a step in right direction

towards making India as an arbitration hub. Setting up of ACI, timelines for completion

of Arbitration, limited scrutiny of awards, confidentiality can be termed as pros of the

Act. Having said this the amendment too is not immune from defects and ambiguities. A

detailed set of rules governing the working of the ACI, ensuring its independence and

impartiality alongwith other suggestions provided in this paper may provide perfect step

towards making India an Arbitration hub.

References

i

Sec 11 (3A) the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

ii

Sec 11 (3A)(ii) the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

iii

Supra note 7

iv

Lok Sabha nod to bill to amend arbitration law, PTI, Available at,

http://www.ptinews.com/news/10751772_Lok-Sabha-nod-to-Act-to-amend-arbitration-

law.html, accessed on 30th August 2019

www.ijmer.in 49

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

ISSN: 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR – 6.014; IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 9(5), SEPTEMBER 2019

v

Sec 43 B (2), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

vi

Sec 43 D (1), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

vii

Sec 43D (2) (a), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

viii

Sec 43D (2) (d), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

ix

Sec 43D (2) (h), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

x

Sec 43D (2) (j), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xi

Page 62-63, Justice B.N. Srikrishna Committee Report

xii

Dr. George Amit, NPAC's Arbitration Review: The 2019 Arbitration Amendment Act

and the changes it ushers in - A Primer, August 12 2019, available at,

https://barandbench.com/npac-arbitration-review-2019-arbitration-amendment-act/

xiii

CIVIL APPEAL Nos.2879-2880 OF 2018

xiv

Section 29A (1), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xv

Section 23 (4), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xvi

Proviso to Section 29A (4), the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xvii

(2009) 17 SCC 796

xviii

Civil Appeal No. 8367 of 2018

xix

Sec 34 (2) the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xx

Section 42B, the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019. Similar

provisions is provided under Section 25, International Arbitration Act (Chapter 143a)

(Singapore); Section 20, Arbitration Act (Chapter 10) (Singapore).

xxi

See sec 43C, the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xxii

See sec. 42A, the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

xxiii

The validity of arbitration agreement shall be left open for checking by the arbitration

tribunal in accordance with the ‘Competence Competence (Kompetenz-Kompetenz)’

principal (see Sec. 16, the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996)

www.ijmer.in 50

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3621180

You might also like

- ADRDocument8 pagesADRvinita choudharyNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute ResolutionDocument22 pagesAlternative Dispute ResolutionAprajitaNo ratings yet

- Arbitration ActDocument22 pagesArbitration ActrudrakshiNo ratings yet

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2019Document7 pagesArbitration and Conciliation Act 2019jyoti chouhanNo ratings yet

- QLJHLQKNFDocument15 pagesQLJHLQKNFnishit gokhruNo ratings yet

- Adr Final JPDocument21 pagesAdr Final JPDeeptangshu KarNo ratings yet

- Arbitration & Conciliation Amendment Act, 2015Document10 pagesArbitration & Conciliation Amendment Act, 2015Kritik AgrawalNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Explication of Amendments Introduced by The Arbitration & Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019Document3 pagesA Detailed Explication of Amendments Introduced by The Arbitration & Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 Section 11-Appointment of ArbitratorDocument3 pagesThe Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 Section 11-Appointment of ArbitratorSaakshi SharmaNo ratings yet

- AdrDocument13 pagesAdrShreejana RaiNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Amendment 2019Document4 pagesArbitration Amendment 2019Pratik ShendeNo ratings yet

- Int Comm Arbitration Document PDFDocument103 pagesInt Comm Arbitration Document PDFHemantPrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Analysis: Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 Key ChangesDocument4 pagesAnalysis: Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 Key ChangesMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Taking Steps For Creating India As A Centre of Domestic and International Arbitrations, EtcDocument6 pagesTaking Steps For Creating India As A Centre of Domestic and International Arbitrations, EtcDrishti TiwariNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Arbitration in IndiaDocument4 pagesChallenges of Arbitration in IndiaBellNo ratings yet

- An Explication of Amendments Introduced PDFDocument3 pagesAn Explication of Amendments Introduced PDFMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Cases On IbcDocument20 pagesCases On IbcShatakshi SinghNo ratings yet

- 2018LLB111 VI-sem ADR-projectDocument25 pages2018LLB111 VI-sem ADR-projectKusum Kali MitraNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Arbitral AwardsDocument28 pagesEnforcement of Arbitral AwardsSakshi100% (1)

- Indus Biotech V. Kotak India Venture - Failed Attempt To Reconcile Insolvency and Arbitration RegimeDocument18 pagesIndus Biotech V. Kotak India Venture - Failed Attempt To Reconcile Insolvency and Arbitration RegimeBeehuNo ratings yet

- 246th Report of Law Commission of IndiaDocument3 pages246th Report of Law Commission of IndiaAnshu Goel50% (2)

- Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2019Document6 pagesArbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2019AayushNo ratings yet

- HCCL Judgment PDFDocument95 pagesHCCL Judgment PDFNitish KumarNo ratings yet

- Research Report On International Commercial Arbitration: Concept and CasesDocument5 pagesResearch Report On International Commercial Arbitration: Concept and CasesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Faculty of LawDocument25 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Faculty of LawZeeshan AliNo ratings yet

- Arbitration in IndiaDocument19 pagesArbitration in IndiapapapNo ratings yet

- Comments Chiraiya Saruparia, Drishti Tiwari Write UpDocument6 pagesComments Chiraiya Saruparia, Drishti Tiwari Write UpDrishti TiwariNo ratings yet

- Commercial Arbitration in India and Recent Developments: International Journal of LawDocument2 pagesCommercial Arbitration in India and Recent Developments: International Journal of LawMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Comments Chiraiya Saruparia, Drishti Tiwari Write UpDocument6 pagesComments Chiraiya Saruparia, Drishti Tiwari Write UpDrishti TiwariNo ratings yet

- HE Hift Towards Institutional Arbitration: C A (A A 2019)Document21 pagesHE Hift Towards Institutional Arbitration: C A (A A 2019)MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Emergency Arbitration-Working and EnforceabilityDocument15 pagesEmergency Arbitration-Working and EnforceabilityoptimusautobotNo ratings yet

- Arbitration and Mediation - 0Document4 pagesArbitration and Mediation - 0Tribhuvan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Recent Reforms On Indian Arbitration Law: Rohit MoonkaDocument14 pagesImpact of The Recent Reforms On Indian Arbitration Law: Rohit MoonkaAnkit YadavNo ratings yet

- ADR Unit-1 Reading MaterialDocument19 pagesADR Unit-1 Reading MaterialEarl JonesNo ratings yet

- PDF Upload 364293Document16 pagesPDF Upload 364293Dhiraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Insolvency Law in Review - March 2021Document23 pagesInsolvency Law in Review - March 2021Abhishek MishraNo ratings yet

- ADR2Document7 pagesADR2Sidd ZeusNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Amendment BillDocument4 pagesArbitration Amendment BillAyush BakshiNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Amendments 2018Document4 pagesArbitration Amendments 2018Arjun RavindranNo ratings yet

- Damodarm Sanjivaya National Law University, Sabbavaram: Role of Chief Justice in Appointment of ArbitratorsDocument37 pagesDamodarm Sanjivaya National Law University, Sabbavaram: Role of Chief Justice in Appointment of ArbitratorsKranthi Kiran TalluriNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution and Legal Aid - Project ReportDocument15 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution and Legal Aid - Project ReportmehakNo ratings yet

- BgsDocument106 pagesBgsPrachi JainNo ratings yet

- 2019 4 1501 18556 Judgement 27-Nov-2019Document95 pages2019 4 1501 18556 Judgement 27-Nov-2019Mukesh Prasad GuptaNo ratings yet

- Draft Project On International Commercial ArbitrationDocument86 pagesDraft Project On International Commercial Arbitrationaushim khullarNo ratings yet

- Main - ADRDocument136 pagesMain - ADRMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13Document38 pagesLesson 13sirisha siriNo ratings yet

- The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Ordinance, 2015Document3 pagesThe Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Ordinance, 2015Lalit GoelNo ratings yet

- Arbitration - Future of Arbitration in IndiaDocument12 pagesArbitration - Future of Arbitration in IndiaPayal GolimarNo ratings yet

- Book of Abstracts National Seminar On Strengthning Enforcement of Contracts 1Document178 pagesBook of Abstracts National Seminar On Strengthning Enforcement of Contracts 1Bodhiratan Barthe100% (1)

- Supplement JIGL December 2023 ConsolidatedDocument37 pagesSupplement JIGL December 2023 Consolidateddivyanshi. 28No ratings yet

- Kartikay AgarwalDocument13 pagesKartikay AgarwalKartikay AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law India Critical AnalysisDocument23 pagesArbitration Law India Critical AnalysisKailash KhaliNo ratings yet

- IBC ProjectDocument5 pagesIBC ProjectRehaan DanishNo ratings yet

- 2019-08 - Akanksha Bohra ICADocument15 pages2019-08 - Akanksha Bohra ICAAkanksha BohraNo ratings yet

- Adr 3Document4 pagesAdr 3sanampreet virkNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Effectiveness of ADR - A Study On Arbitration in The Construction SectorDocument6 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution Effectiveness of ADR - A Study On Arbitration in The Construction SectorFALAQ PATELNo ratings yet

- ADR Unit-1 Topic-1: Historical Background of Arbitration & ConciliationDocument4 pagesADR Unit-1 Topic-1: Historical Background of Arbitration & ConciliationEarl JonesNo ratings yet

- Interim Relief Measures Under Arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996 Alternative Dispute Resolution, ProjectDocument13 pagesInterim Relief Measures Under Arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996 Alternative Dispute Resolution, ProjectDivija PiduguNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Commercial Dispute Resolution in China: An Annual Review and Preview 2020From EverandCommercial Dispute Resolution in China: An Annual Review and Preview 2020No ratings yet

- Competitionact2002 160403062713Document67 pagesCompetitionact2002 160403062713ruksi lNo ratings yet

- 05 ContentDocument4 pages05 ContentMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Grounds For Challenging Foreign Arbitral Award PDFDocument19 pagesGrounds For Challenging Foreign Arbitral Award PDFChandan KumarNo ratings yet

- Effects of ForeignDocument42 pagesEffects of ForeignMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards in International Commercial Arbitration A Study With Reference To IndiaDocument1 pageRecognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards in International Commercial Arbitration A Study With Reference To IndiaMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- 5A. Competition Act PDFDocument30 pages5A. Competition Act PDFzeerak jabeenNo ratings yet

- Faizys ProjectDocument124 pagesFaizys ProjecthomitaNo ratings yet

- Competition Law - An Overview - Unit - 1 - 1.3.3Document15 pagesCompetition Law - An Overview - Unit - 1 - 1.3.3MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Arbitrability and Public Policy in Regard To The Recognition andDocument227 pagesArbitrability and Public Policy in Regard To The Recognition andkatyayaniNo ratings yet

- Proposed Amendments & Judicial Pronouncements in ArbitrationDocument32 pagesProposed Amendments & Judicial Pronouncements in ArbitrationMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Foreign Arbitration Awards & Attitude of Indian Legal Regime: The Saga of Constant Flip-FlopDocument20 pagesForeign Arbitration Awards & Attitude of Indian Legal Regime: The Saga of Constant Flip-FlopMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- A I F - H: E F A A: Rbitration IN Ndia NOT FOR THE Aint Earted Nforcing Oreign Rbitral WardsDocument18 pagesA I F - H: E F A A: Rbitration IN Ndia NOT FOR THE Aint Earted Nforcing Oreign Rbitral WardsMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Award in India: by Ginny Jetley RautrayDocument17 pagesEnforcement of Foreign Arbitral Award in India: by Ginny Jetley RautrayVarsha ReddyNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Foreign AwardsDocument6 pagesEnforcement of Foreign AwardsMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards in India: M Ittv of HatoiDocument216 pagesEnforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards in India: M Ittv of HatoiMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Foreign AwardsDocument39 pagesEnforcement of Foreign AwardsMAHANTESH G100% (1)

- NITI ReportDocument17 pagesNITI ReportArihant RoyNo ratings yet

- Dissertation PDFDocument86 pagesDissertation PDFAnonymous lB27TYNo ratings yet

- International Commercial Arbitration: International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics No. 5 2018, 1635-1644Document10 pagesInternational Commercial Arbitration: International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics No. 5 2018, 1635-1644MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- NITI ReportDocument17 pagesNITI ReportArihant RoyNo ratings yet

- Proposed Amendments & Judicial Pronouncements in ArbitrationDocument32 pagesProposed Amendments & Judicial Pronouncements in ArbitrationMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Commercial Arbitration in India: Dr. Pankaj Kumar Gupta Sunil MittalDocument6 pagesCommercial Arbitration in India: Dr. Pankaj Kumar Gupta Sunil MittalMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- 103-MOUDGIL-Judicial Response To International Commercial ArbitrationDocument15 pages103-MOUDGIL-Judicial Response To International Commercial ArbitrationHarsh Harsh VardhanNo ratings yet

- 14 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument72 pages14 - Chapter 4 PDFMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Jurisdictional Issues in International Arbitration With Special Reference To IndiaDocument23 pagesJurisdictional Issues in International Arbitration With Special Reference To IndiaMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Dissertation PDFDocument86 pagesDissertation PDFAnonymous lB27TYNo ratings yet

- Select Indian & Foreign Legal Articles: PpendixDocument66 pagesSelect Indian & Foreign Legal Articles: PpendixMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- Int Comm Arbitration Document PDFDocument103 pagesInt Comm Arbitration Document PDFHemantPrajapatiNo ratings yet

- The New Delhi International Arbitration Centre Act, 2019Document11 pagesThe New Delhi International Arbitration Centre Act, 2019MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- International Commercial Arbitration: International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics No. 5 2018, 1635-1644Document10 pagesInternational Commercial Arbitration: International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics No. 5 2018, 1635-1644MAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- GRE Big Book WordsDocument32 pagesGRE Big Book Wordsapi-3696482100% (1)

- CID 20231122201002378796 777900 CIDROC IpayccDocument6 pagesCID 20231122201002378796 777900 CIDROC Ipayccnvm creativeNo ratings yet

- The Champion Legal Ads: 01-05-23Document32 pagesThe Champion Legal Ads: 01-05-23Donna S. SeayNo ratings yet

- Section 115 BisDocument2 pagesSection 115 BisAndré Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Women DirectorDocument6 pagesWomen DirectorMayank Sen100% (1)

- DS11 CompleteDocument6 pagesDS11 CompletesarahNo ratings yet

- MOU On DSWD CSO Thru Pantawid Edited VersionDocument3 pagesMOU On DSWD CSO Thru Pantawid Edited VersionSapere AudeNo ratings yet

- ITB 2021-03 Board Resolution No. 80, 81, 82, 84 & 85 Series of 2021Document2 pagesITB 2021-03 Board Resolution No. 80, 81, 82, 84 & 85 Series of 2021DASURECOWebTeamNo ratings yet

- Ethics of PNPDocument6 pagesEthics of PNPZora IdealeNo ratings yet

- Mistake EssayDocument2 pagesMistake EssayQasim GorayaNo ratings yet

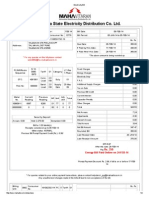

- Electricity BillDocument2 pagesElectricity Billrahuldbajaj2011No ratings yet

- DD Env 12718-2001Document46 pagesDD Env 12718-2001jamNo ratings yet

- 2020-06-26 - Complaint 15 (F)Document321 pages2020-06-26 - Complaint 15 (F)Ben PavoneNo ratings yet

- B BB Bio Jackpor AlemanDocument19 pagesB BB Bio Jackpor AlemanEsteban Enrique Posan BalcazarNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 5002Document2 pagesG.R. No. 5002Josef elvin CamposNo ratings yet

- ACKO Car Insurance-Jul'21Document5 pagesACKO Car Insurance-Jul'21Roman PatelNo ratings yet

- Dupont Artistri Product Offering: Textile Inks and AuxiliariesDocument2 pagesDupont Artistri Product Offering: Textile Inks and AuxiliariesAymen HajjiNo ratings yet

- Managing Social Responsibility: and EthicsDocument48 pagesManaging Social Responsibility: and EthicsMehdi MohmoodNo ratings yet

- Case Digest G.R. No. 178920Document7 pagesCase Digest G.R. No. 178920WALTER IVANHOENo ratings yet

- Demand To VacateDocument1 pageDemand To VacateJuds JDNo ratings yet

- TOTAL Income: POSSTORE JERTEH - Account For 2021 Start Date 8/1/2021 End Date 8/31/2021Document9 pagesTOTAL Income: POSSTORE JERTEH - Account For 2021 Start Date 8/1/2021 End Date 8/31/2021Alice NguNo ratings yet

- Rules Flow ChartDocument6 pagesRules Flow Chartmrgoldsmith23100% (7)

- Filing Particulars of Claim38 1Document29 pagesFiling Particulars of Claim38 1Público DiarioNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 - Unit 4 - AudioDocument20 pagesLecture 5 - Unit 4 - Audiolipe faNo ratings yet

- Motion Telephonic HearingDocument3 pagesMotion Telephonic Hearingheather valenzuelaNo ratings yet

- U.S. Border Patrol Monthly Apprehensions (FY 2000 - FY 2019)Document20 pagesU.S. Border Patrol Monthly Apprehensions (FY 2000 - FY 2019)Stephen LoiaconiNo ratings yet

- Debulgado v. CSCDocument20 pagesDebulgado v. CSCJune DoriftoNo ratings yet

- United India Insurance Company Limited: This Document Is Digitally SignedDocument2 pagesUnited India Insurance Company Limited: This Document Is Digitally Signedsharoon ahamadNo ratings yet

- 338 MASANGYA Casela v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pages338 MASANGYA Casela v. Court of AppealsCarissa CruzNo ratings yet

- Proposed Syllabus Taxation 1 Atty. SaniDocument13 pagesProposed Syllabus Taxation 1 Atty. SaniZubair BatuaNo ratings yet