Professional Documents

Culture Documents

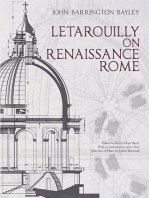

Betts, Structural Innovation and Structural Design in Renaissance Architecture

Uploaded by

Claudio CastellettiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Betts, Structural Innovation and Structural Design in Renaissance Architecture

Uploaded by

Claudio CastellettiCopyright:

Available Formats

Structural Innovation and Structural Design in Renaissance Architecture

Author(s): Richard J. Betts

Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians , Mar., 1993, Vol. 52, No. 1

(Mar., 1993), pp. 5-25

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural

Historians

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/990755

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/990755?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Society of Architectural Historians and University of California Press are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural

Historians

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Structural Innovation and Structural Design in

Renaissance Architecture

RICHARD J. BETTS University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The characteristic structural forms of large Renaissance churches- lack of technical skill was notorious for having caused structural

domes, drums, pendentives, and barrel vaults-were the products of failure at Saint Peter's. On this basis, Ackerman draws a sweep-

innovation in theory and practice during the later fifteenth century in ing conclusion: "This lack of technical discipline," he says,

Italy that culminated in Bramante's projectsfor the new Saint Peter's. "may explain in part why the High Renaissance is one of the

Significant ideas were contributed by Leon Battista Alberti, Francesco few great eras in architectural history in which a new style

di Giorgio, and Leonardo da Vinci. Francesco di Giorgio's geometrical emerges without the assistance of any remarkable structural

methods of design for churches as described in his second treatise in- innovation."2 That Ackerman's view has been widely accepted

corporate a procedure for calculating the thickness of walls bearing is indicated by frequent citations of his article, and by the paucity

vaults. Francesco di Giorgio tested the procedure in his own churches, of modern engineering studies of Renaissance structures.3

and it was later used by Bramante. The state of modern scholarship on the question of structural

innovation is curious in view of the fact that we can know far

more about Renaissance than about medieval structures. Modern

BEGINNING WITH BRAMANTE'S PROJECTS for the new

Saint Peter's of 1505-1506, the Renaissance dome and barrel techniques of structural analysis may tell us much about the

vault, which had been used sporadically in the later fifteenth structural behavior of ribbed vaults and flying buttresses, but we

century, displaced the Gothic ribbed vault as decisively as the know almost nothing about how their architects designed them

because they left no direct records of their secrets. One of the

ribbed vault had displaced the barrel vault of the Romanesque.

fundamental innovations of Renaissance architecture was the

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as in the twelfth century,

the advent of a new style was accompanied by a change in reinvention, by Leon Battista Alberti, of architectural theory as

structural form, but architectural historians have not assigned a self-conscious discipline. Thanks to the treatises of the later

the same significance to structural innovation in both cases. We fifteenth century, we can understand how Renaissance archi-

study the structures of Gothic churches because we believe that tects, including Bramante, thought about the structures of their

structural innovation had a determining influence on their forms., buildings, and we can observe the invention and testing of new

Believing the contrary about Renaissance architecture, we have methods of design for new kinds of structures.

not studied structures of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Renaissance vaulting was not created by simply reviving an-

except Brunelleschi's dome, which is in fact a ribbed vault. cient Roman forms. The Romans used groin vaults, not barrel

Perhaps the most influential modern study of structural design vaults, to cover large spans, and they never dared to put a dome

in Renaissance architecture is James S. Ackerman's article "Ar- on top of them, much less a dome elevated on a drum. The

chitectural Practice in the Italian Renaissance," published in this combination of dome, drum, pendentives, and barrel vaults that

journal in 1954. Professor Ackerman argues that Renaissance we see in Saint Peter's and so many later churches was, at the

architects were concerned primarily with ideal forms and pro-

portions and that they left structural problems to the craftsmen 2. J. S. Ackerman, "Architectural Practice in the Italian Renaissance,"

whom they employed to construct their buildings. As his leading JSAH, VIII, 1954, 3-11. For further arguments on this point, see idem,

example of an artist turned architect who was indifferent to the "Notes on Bramante's Bad Reputation," in Studi Bramanteschi, Rome,

1974, 339-349.

responsibilities of structural design, he cites Bramante, whose

3. See, for example, R.J. Mainstone, "Structural Theory and Design

before 1742," Architectural Review, CXLIII, no. 854, Apr. 1968, 303-

310; and C. Wilkinson, "The New Professionalism in the Renaissance,"

A version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the

in S. Kostof, ed., The Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession,

Society of Architectural Historians in Albuquerque on 3 April 1992. I

New York and London, 1977, 124-160. The only modern engineering

am indebted to Carol Bolton Betts, Lloyd Leffers, Robert Mark, Henry study of a Renaissance structure known to me is E. C. Robison, "A

Millon, and Sergio Sanabria for good questions and helpful comments.

Structural Study of the Michelangelo and Della Porta Designs for the

1. See, for example, R. Mark, Experiments in Gothic Structure, Cam- St. Peter's Dome," in C. A. Brebbia, ed., Structural Repair and Maintenance

bridge, Mass., 1982. of Historical Buildings, Basel and Boston, 1989, 23-31.

JSAH LII:5-25. MARCH 1993 5

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

time of its appearance in the fifteenth century, a new structural crossing. The architect of record was Bernardo Rossellino, but

form, neither Roman nor Romanesque. Since Renaissance ar-

the design of the project is usually attributed to Alberti, a close

chitects had inherited nothing in the way of theory to guidefriend of Pope Nicholas, to whom he dedicated De re aedificatoria

in about 1452.6 When Nicholas V died in 1455, the foundations

them in designing these complex systems of vaults, they had to

invent and test methods of design that would allow them to and part of the walls of the choir were standing. Little more

build with reasonable confidence in the success of their enter-was done until after 1506, when Bramante completed the walls

prise. Their success is attested by the fact that incidents of spon-and covered the choir with a barrel vault.

taneous structural failure are rare in the history of Renaissance What we know about the project of Nicholas V comes from

architecture. There is no Renaissance Beauvais. This seems all a description written by Gianozzo Manetti in his biography of

the more remarkable when we consider that it was not until the pope,7 and from several drawings of the early sixteenth

the seventeenth century that architects could take advantage ofcentury that are now in the Uffizi. The most useful of the

inventions in mathematics and mechanics that would lead to drawings is Uffizi 20A, a red chalk drawing made by Bramante

modern techniques of structural analysis.4 or a close assistant, which shows, in plan, the old Saint Peter's,

Bramante's Saint Peter's was the culminating event in a re-the choir and transept of Nicholas V, and two partial projects

markable episode of structural innovation whose history we canfor the new basilica (Fig. 24).8 The paper is gridded, so we can

know in some detail. The story of Renaissance vaulting begins,read dimensions from it, and we can reconstruct in outline the

as do so many stories in Renaissance architecture, with Alberti.plan of the choir and transept as envisaged by Nicholas V and

In De re aedificatoria, he extols the virtues of vaulted ceilings for his architects (Fig. 1).9 The pope and his builders intended to

temples: "I would expect the roof of a temple to be vaulted, forretain the old basilica and replace only the apse and transept

the sake of dignity and also durability."5 He attributes theirwith a new structure. The crossing would have been a square

durability to their superior resistance to fire, and he cites ex- of 44 braccia, or 24.5 meters, corresponding to the width of the

amples of ancient temples that had burned. He goes on to rec-

ommend coffering, as in the Pantheon, and he describes a meth- 6. For the most complete, recent studies of the project of Nicholas

V, see T. Magnuson, Studies in Roman Quattrocento Architecture (Figura,

od for forming coffers, implying that he had used it. But he

IX), Stockholm, 1958, 163-216; and G. Urban, "Zum Neubau-Projekt

says nothing about how to design the structure of a vaultedvon St. Peter unter Papst Nikolaus V," in H. M. von Erffa and H.

Herget, eds., Festschriftfir Harald Keller zum sechzigsten Geburtstag, Darm-

ceiling, nor does he describe it in such a way that we can know

stadt, 1963, 131-173. Rossellino's work is documented by a series of

what particular forms of vaulting he had in mind. From the

payment accounts beginning in 1451. The attribution to Alberti of the

fact that he recommends coffering in vaults, we may infer that design of the project of Nicholas V goes back to a late fifteenth-century

Alberti preferred barrel vaults, and we can attribute to his in-diary and was repeated by Vasari, among others.

7. The entire text of Manetti's vita of Nicholas V is in Magnuson,

fluence the Renaissance preference for that form. We can even

Studies in Roman Quattrocento Architecture, 351-362. Magnuson discusses

attribute to him what may have been the first attempt to combineManetti's description of the project for Saint Peter's line by line on pp.

a barrel vault and a dome at Saint Peter's in Rome, half a century 180-200.

before Bramante's time. 8. Uffizi 20A was first published, in color and at full scale, by H.

Freiherr von Geymiiller, Die urspriinglichen Entwiirfefiir Sanct Peter

In 1451, Nicholas V commissioned a project to remodel the

Rom von Bramante, Raphael Santi, Fra Giocondo, den Sangallo's u. a

old Saint Peter's by adding a new choir, transept, and domedvols., Vienna, 1875, I, 175-196 and passim, and II, pls. 9-11.

9. The solid black area in my Figure 2 shows the project of Nicho

4. For brief surveys of Renaissance structural design and the begin-V as it appears in Uffizi 20A, superimposed on a copy of the drawi

nings of modern practice, see W. B. Parsons, Engineers and Engineering from which I have erased Bramante's projects for the sake of clarit

in the Renaissance, 2d ed. (repr.), Cambridge, Mass., 1968, 481-492; andThe squares in the grid measure 5 palmi, but it is convenient to g

R. Mainstone, "Structural Theory and Design before 1742." Parsonsmost of the dimensions in braccia because Manetti does so. One brac

points out that although Renaissance architects seem to have been awareequals 2.5 palmi, or 0.5585 meter. The grid is not entirely accura

of stresses in structural members, they had no understanding of theirand there are discrepancies between the text of Manetti and the drawin

nature or intensity. A key discovery leading to modern theories ofMagnuson endeavored to resolve these discrepancies, and I have f

structural design was Galileo's analysis of stress in a cantilevered beamlowed his very thorough analysis of the dimensions. All vertical

published in 1638 in the Dialoghi delle nuove scienze. Mainstone regardsmensions come from Manetti.

Giovanni Poleni's analysis of cracks in the dome of Saint Peter's in 1742 Manetti refers to a dome at the crossing, and I have indicated

as the beginning of modern structural analysis; cf. G. Poleni, Memorie probable form using a light line. Magnuson and Urban tried in differ

istoriche della gran cupola del Tempio Vaticano e de' danni di essa, e de'ways to reconstruct the project with a dome, groin vaults, and numero

details including transverse arches and columns. The available inf

ristoramenti loro, divise in libri cinque, Padua, 1748. He suggests that earlier

methods of design were probably geometrical. The results of my ownmation does not fully support their conjectures. The most importan

research confirm Mainstone's supposition.

missing information includes definition of the eastern side of the trans

5. L. B. Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, tr. J. Rykwert,and crossing. Uffizi 20A shows the western walls, which were not bu

N. Leach, and R. Tavernor, Cambridge, Mass., 1988, 221. Cf. L. B.in the time of Nicholas V, but not the eastern walls. We may surm

Alberti, L'architettura (De re aedificatoria), ed. G. Orlandi, Milan, 2 vols.,

that this area had not been defined by Alberti or Rossellino. Accordi

1966, II, 613: "Templis tectum dignitatis gratia etiam perpetuitatisto Manetti, they intended to build a dome; according to Uffizi 20

maxime esse testudinatum velim."

they did not know how they would do it.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 7

old nave, surmounted by a dome and lantern reaching 100 braccia

in height. The transepts were to have been 78 braccia long, with

groin vaults 80 braccia high. The choir was to have been 80

braccia long, and although Manetti says nothing about its vault

we can assume that it would have been 80 braccia high, as in

the transepts. The form of the choir vault is problematic.10 If

groin vaults were intended for the transepts, as Manetti says,

then we could reasonably expect the same in the choir. But if

we assume that the bays of the choir were framed by transverse

arches corresponding to the exterior buttresses, then the choir

would have two bays of somewhat different dimensions. This

would be unsuitable for groin vaults, but a choir of that form

could be covered conveniently by a barrel vault. The structural

.

forms shown in Uffizi 20A strongly imply that a barrel vault

of a barrel vault rather than the concentrated loads and thrusts

was intended when the foundations were built. ..., . , , I

According to Uffizi 20A, the walls of the choir and transept

were 30 palmi, or 6.7 meters, thick and reinforced by buttresses.

Torgil Magnuson, assuming the use of groin vaults, argued that

such mighty walls would have been expensive to build and

before 1449. ..St. Lawrence in a basilica with transepts

structurally unnecessary. He accounted for them by proposing

va on cou Fa s archite e i

that the new choir and transept were intended to serve as part

of a new circuit of fortifications around the Borgo Vaticano. In . . ' ' ' . -; , ,

Magnuson's view, the elements shown projecting from the ex-

terior walls in Uffizi 20A would have been defensive towers

Fig. bastions,

surmounted by battlements. But these do not resemble 1. Leon Battista Alberti and Bernardo R

Rome, c. 1451. Reconstruction of the choir

they lack the interior spaces and passageways that would make

V superimposed on Uffizi 20A (author).

them useful as such, and their site would not be appropriate for

fortifications of that kind.'" They are what they appear to be,

solid buttresses intended to reinforce the walls.ofThe

a extraor-

barrel vault rather than the concentr

dinary thickness of the walls can only be attributed to someby groin vaults and ribbed vau

presented

structural purpose, and that seems reasonable if we Two

suppose that items also suggest that a barr

other

the walls were intended to carry the continuous load

forand thrust

the choir. The first is a cycle of fres

from the lives of Saints Stephen and Law

Angelico

10. Magnuson, Studies in Roman Quattrocento Architecture, 199, arguesin the chapel of Nicholas V at

that the choir could have been covered by groin vaults in two 1449.

before bays, St. Lawrence is ordained in a

framed by transverse arches. Recognizing the inadequacy of our infor-

and groin vaults carried by walls and colum

mation, he goes on to say that the ceiling of the choir ". .. could have

alms

been of a different kind of vaulting, or a barrel vault, or a flatin front of a hall closed by an apse a

wooden

ceiling." Urban, "Zum Neubau-Projekt von St.-Peter," 160-161,

vault ob-

carried on columns.' Fra Angelico'

serves that the choir could have been covered by a barrel vault or groin

possible "painter's architecture," but it

vaults, and that he could not conclusively argue for one or the other.

Nicholas

11. Cf. Magnuson, Studies in Roman Quattrocento Architecture, V contemplated barrel vaults as

199-

If we at

200. Urban agreed with Magnuson on this point. A fortress replace

the the colonnades of the "Sai

location of the choir and transept would have been improbable. The

uting Alms" with structurally realistic w

site guards neither the perimeter nor the high ground, and it faces toward

space would resemble the choir of Nich

the Vatican Hill, whose height, according to Magnuson's contour map,

barrel

is 47.5 meters above grade level at the basilica. Furthermore, vault. The second item which sugge

Manetti

clearly says that the choir was to have been illuminated by aintended

was "crown" for the new choir is the fact t

of round windows in its walls, and Magnuson proposes, on documentary

built there by Bramante.

evidence, that large, arched windows would have been installed below

the roundels. The presence of such windows would have greatly di-

Construction of a large barrel vault, 2

44.6

minished the defensive value of the walls and buttresses if meters

they had high, sustained and buttressed

been used as bastions. To paraphrase Magnuson's argument, one might

ask why anyone would go to the trouble and expense to build very thick

walls as a means of defense and then render them useless for that

12. purpose

Cf. J. Pope-Hennessy, Fra Angelico, 2d

by opening them with windows. 212-214, pls. 111-112 and frontispiece.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

have been a very risky undertaking in 1451. Vaults cesco di Giorgio later returned to the form of the choir of

of nearly

that size had been erected during the fourteenth century at used barrel vaults carried by stout walls without

Nicholas V and

Florence cathedral, but they are ribbed vaults and so aisles

could or not

external buttresses at San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti

have served as a useful model for the architects of Nicholas

in Urbino,V.begun in 1483, and at Santa Maria delle Grazie al

The most recent experience in constructing barrel vaults

Calcinaiohad

in Cortona, designed in 1484 (Figs. 12 and 16). The

occurred during the twelth century, in Romanesque naves that

last of the fifteenth-century barrel-vaulted churches is Francesco

were considerably smaller than the choir of Nicholas V and Santo Spirito in San Maurizio in Siena, designed

di Giorgio's

buttressed by aisles and galleries. The extraordinary thickness

about 1498.15 Its nave is covered by a lunette vault, perhaps the

of the walls in the choir of Nicholas V tells us that Alberti and

earliest example of a type that would be commonly used in large

Renaissance churches after 1500.16

Rossellino understood the risk, and in this instance Ackerman's

thesis may well be correct. To Alberti we should attribute the

Of the nine barrel-vaulted churches listed above, four can be

interior proportions of the new choir and transept and, aboveto Francesco di Giorgio. He had more experience in

attributed

all, the radical idea of building a barrel vault surmounted byof aconstruction than any other architect of the fifteenth

this type

dome and drum. But Alberti's treatise shows him to have been

century, and his accomplishments had brought him some rep-

ignorant of structural design.13 We can reasonably attribute

utation asto

an expert in structures. In the summer of 1490 he

Rossellino the key structural decision in the choir of Nicholas

V, which was the determination of the thickness of the walls.

15. For Santo Spirito in San Maurizio, see R. Papini, Francesco di

We have no way of knowing how he did this, so weGiorgio,

can onlyarchitetto, Florence, 1946, 3 vols., I, 111-112, and III, pl. 6, no.

assume that he guessed well and included a large safety4; factor.14

and G. H. Fehring, "Studien iiber die Kirchenbauten des Francesco

di Giorgios," Ph.D. diss., Wiirzburg, 1956, 156-180. The attribution

His walls were certainly adequate, because eventually they did

is not documented. Papini attributes the church to Francesco di Giorgio,

carry a barrel vault. whereas Fehring thinks it was designed by a follower under his influ-

ence, perhaps Peruzzi. Curiously, Fehring remarks on the innovative

The choir of Nicholas V was the first of a series of experiments

aspect of the nave vault, as the first lunette vault in Renaissance archi-

in the construction of barrel vaults that continued through the

tecture, but then he says that it is the weakest part of the church and

end of the fifteenth century. At San Sebastiano in Mantua, begun

therefore could not have been designed by Francesco di Giorgio. Since

c. 1460, Alberti again used barrel vaults carried by solid walls.

Francesco di Giorgio died in 1501, we can be sure that he could not

have supervised construction of the vaults. Construction of the church

A somewhat different system, inspired in part by the Basilica of

was probably carried out by one of his assistants, perhaps Giacomo

Maxentius, was used by an unknown architect at the abbey

Cozzarelli, who had been with him since before he went to Urbino in

church at Fiesole in the 1460s, and by Alberti at Sant'Andrea

1476. The design of Santo Spirito should not be attributed to Cozzarelli

in Mantua, designed in 1470-1472. In both churches,because

the he was not an innovative architect. We can reasonably exclude

high

Peruzzi as a candidate for this attribution because he was not yet twenty

vaults of the nave are buttressed by deep transverse walls rising

years old at the time it was designed. We are left with Francesco di

between the chapels. Another system, essentially Romanesque,

Giorgio as the architect of Santo Spirito, and perhaps the inventor of

with aisles, was used by Francesco di Giorgio in the the lunette vault.

cathedral

16. My survey does not include a group of groin-vaulted churches

of Urbino, probably designed in 1475-1476, and by Bramante

constructed mostly in Rome in the fifteenth century. Among these were

at Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan, in about 1478. Fran-

the first completely new Renaissance churches in Rome, Santa Maria

del Popolo, begun c. 1472 by Sixtus IV, and Sant'Agostino, begun c.

13. In De re aedificatoria, III.ii, Alberti discusses foundations and

1478 by says

Cardinal d'Estouteville. Cf. G. Urban, "Die Kirchenbaukunst

that they should be broader than the walls. He cites snowshoes as an in Rom," RomischesJahrbuch fiir Kunstgeschichte, IX-

des Quattrocento

illustration of the principle, and he says that the precise dimensions

X, 1961-1962,of73-288. Use of the groin vault was limited to Rome

the footings must be calculated by a geometrical method that he obviously

and was had inspired by the ruins of ancient baths and the Basilica

described in his mathematical commentaries. Cf. Alberti, Onofthe Art of

Maxentius. All of the Roman churches with groin vaults appear to

Building in Ten Books, 62-64; and idem, L'architettura, I, 176.

us to be "transitional" structures, half Gothic and half Renaissance, full

14. Rossellino might have used an old rule of thumb. Rodrigoof visible Gil,

conflicts between the two styles. The conflicts are due not

writing in the 1540s and 1550s, declares that a buttress willonly

betosound

the immaturity of Renaissance architecture at this time, but also

if its depth equals one-fourth of the span of the vault; cf. S. L.toSanabria,

the fact that groin vaults are best suited to square, or nearly square,

"The Mechanization of Design in the Sixteenth Century: Thebays Structural

in plan. For this reason, the groin vault proved to be inconvenient,

Formulae of Rodrigo Gil de Hontai6n,"JSAH, XLI, 1982, and 281-293.

its use was abandoned after 1500 in favor of the lunette vault, which

Rossellino's walls are approximately one-fourth the span of combines

the vault.

the superior lighting of the groin vault with the advantages

If we assume that he used a rule similar to that described by Gil, then

of design and aesthetics offered by the barrel vault.

we can say more about Rossellino's understanding of the behavior of

A list of barrel-vaulted churches of the fifteenth century might also

the structure. He would have realized that the load and thrust of a barrel

include Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel at Santa Croce in Florence, com-

vault occur continuously along its lower edge, and so he thought of in

missioned the

1429, and Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria delle Carceri,

entire wall as if it were the buttress of a ribbed or groin vaultbegun in 1485, in Prato. I do not include these because their barrel

presenting

concentrated loads. Romanesque churches probably showed him

vaults theshort, little more than broad arches, and because their

are very

necessity of adding transverse arches to stiffen the vault, and domes

theseare

would

ribbed vaults. The design of both could have been accom-

require additional buttresses because they present additionalmodated

load and

by the structural theory of Brunelleschi, which was presumably

thrust.

that of the fourteenth century.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 9

was called to Milan to design structural modifications to the

crossing of the cathedral so that it could carry a tiburio.17 By

then he had already written two treatises on architecture in

which he described methods of design for all types of cities and

buildings. Included within his methods is a theory of structural

design for barrel vaults that he had tested in his own buildings.

Bramante would later use this theory to design the new Saint

Peter's.

Francesco di Giorgio completed his first treatise in about

1475-1476 and his second in 1489-1492.18 He treats the same

subjects in both, but in quite different ways. Each treatise con-

tains information that cannot be found in the other, and much

of that information is conveyed only in drawings. To understand

Francesco di Giorgio's theory we must correlate the texts and

drawings of both treatises.

17. Several architects from Italy and Germany were summoned to

Milan in the 1480s and 1490s for the same reason. Francesco di Giorgio's

proposal was outlined in a statement and recorded in a model made in

June 1492. His statement and related documents are discussed in A. S.

Weller, Francesco di Giorgio, 1439-1501, Chicago, 1943, 24-26, docs.

LXXVI-LXXXII; and A. Bruschi, "Pareri sul tiburio del duomo di

Milano," in A. Bruschi, ed., Scritti rinascimentali di architettura, Milan,

1978, 319-386. Francesco di Giorgio's model does not survive, so we

do not fully understand his proposal. It has become the subject of some

debate, particularly with regard to Francesco di Giorgio's relationship

to other architects involved in building the tiburio. See C. F. da Passano

and E. Brivio, "Contributo allo studio del tiburio del Duomo di Milano,"

Arte Lombarda, XII, 1967, 3-36; P. C. Marani, "Leonardo, Francesco Fig. 2. Francesco di Giorgio, plans for ideal churches. Turin, Biblioteca

di Giorgio, e il tiburio del Duomo di Milano," Arte Lombarda, LXII, Reale, ms. Saluzzianus 148, fol. 11, c. 1475-1476. Ink on parchment

1981, 81-92; G. Scaglia, "Leonardo e Francesco di Giorgio a Milano (Biblioteca Reale, Turin).

nel 1490," in E. Bellone and P. Rossi, eds., Leonardo e l'etd della ragione,

Milan, 1982,225-254; andJ. Guillaume, "Leonardo and Architecture,"

in P. Galuzzi, ed., Leonardo da Vinci: Engineer and Architect, Montreal, Francesco di Giorgio's first treatise is best known from a

1987, 208-209. parchment manuscript in the Biblioteca Reale in Turin, Saluz-

18. Francesco di Giorgio's second treatise was first published by C.

zianus 148. It contains more than 800 drawings, including thir-

Promis, Trattato di architettura civile e militare di Francesco di Giorgio Martini,

ty-two plans and four elevations of churches (Figs. 2 and 3).

2 vols. and atlas, Turin, 1841. Both treatises were published completely

The drawings explore systematically the types of churches that

with transcriptions of text and illustrations of all drawings, in Francesco

di Giorgio Martini, Trattati di architettura, ingegneria, e arte militare, ed.

can be generated by combining different functional elements,

C. Maltese, 2 vols., Milan, 1967. Another copy of the first treatise, once

owned and annotated by Leonardo da Vinci and later damaged by fire,

geometrical forms, and proportions. They imply that Francesco

was published in facsimile in Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Trattato di

di Giorgio used precise methods of design, but he does not

Architettura: II Codice Ashburnham 361 della Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

discuss his methods in the text of his first treatise, except to

di Firenze, ed. P. C. Marani, Florence, 1979. All of Francesco di Giorgio's

describe, briefly, the proportions of chapels and round churches.

manuscripts have been listed and described in G. Scaglia, Francesco di

The

Giorgio: Checklist and History of Manuscripts and Drawings in Autograph caption of one of the simplest of his basilican plans says

and Copiesfrom c. 1470 to 1687 and Renewed Copies (1764-1839), Beth- that it is a "Tenpio di tre quadri in nel chorpo e uno la magior

lehem, Pa., 1992. For the dating of Francesco di Giorgio's treatises, see

chapella" (A temple with three squares in the body and one in

R. J. Betts, "On the Chronology of Francesco di Giorgio's Treatises:

New Evidence from an Unpublished Manuscript," JSAH, XXXVI, the main chapel) (Fig. 4).19 That is as much as Francesco di

1977, 3-14. Maltese, Scaglia, and Marani disagree with my datingGiorgio

of says about any of his plans in his first treatise, and it

the manuscripts; they assign the first treatise to the 1480s and the second

appears to say precious little about this one.

to the 1490s. I am more than ever convinced that my earlier arguments

Francesco di Giorgio treats churches very differently in his

on dating are correct, however, and they have received an endorsement

of sorts from Arnaldo Bruschi. In Scritti rinascimentali, 19-20 n.second

3, treatise, which is best known from its final, illustrated

Bruschi observes in passing that the second treatise was clearly written

version, a paper manuscript in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale

under the influence of Federico da Montefeltro, whom Francesco di

Giorgio served as ducal architect from 1476 to 1482, and that the

influence of Urbino is altogether lacking in the first treatise. 19. Cf. Francesco di Giorgio, Trattati, ed. Maltese, I, pl. 19 and 256.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

Fig. 4. Francesco di Giorgio, plan for an ideal church. Turin, Biblioteca

Reale, ms. Saluzzianus 148, fol. 12, c. 1475-1476. Ink on parchment

(Biblioteca Reale, Turin).

In the preface to his second treatise Francesco di Giorgio

proudly claimed his drawings as his own inventions. His meth-

Fig. 3. Francesco di Giorgio, plans for ideal churches. Turin, Biblioteca

Reale, ms. Saluzzianus 148, fol. 13v, c. 1475-1476. Ink on parchment ods for designing churches are based on grids and quadrature,

(Biblioteca Reale, Turin).

and they usually involve some combination of the two. He used

grids to achieve correct proportions in the spaces, which he

in Florence, ex-Magliabecchianus II.I.141 (Figs. 5 and 26). The validated with reference to his theory of the Human Analogy,

illustrations of the book on temples in Magliabecchianus II.I.141and he used variations of quadrature to design the structural

forms, among other things. His knowledge of quadrature was

are linear diagrams instead of plans, and the text explains how

probably part of the theory that had been transmitted orally

to draw them. But the second treatise does not fully explain

how geometrical diagrams can be turned into plans with solid from generation to generation of architects throughout the Mid-

dle Ages.

walls capable of bearing vaults and domes. To understand this

point, we must combine information from both treatises, and A simple quadrature series consists of two unequal, concentric

squares, the smaller being erected inside the larger on the mid-

we can do so because when he made the drawings of churches

points of its sides. The series can be extended in both ascending

for his first treatise, Francesco di Giorgio used the geometrical

methods that he would describe only later, in his second trea-and descending manners, and it can include the circumscribed

tise.20 circles of the squares and a second series of squares rotated to

the first by 45 degrees. A more complex quadrature series defines

20. My discussion of two drawings from Saluzzianus 148, below, a variety of smaller squares, rectangles, circles, and line segments

will provide some demonstration of this point, but a full discussion that can be used for many purposes in designing a building.

would be impossible here, given the number of drawings involved.

Suffice it to say that I have studied all of the drawings of churches in

Saluzzianus 148 from this point of view. Only two of them were not no cross-sectional drawings of churches in the first treatise. Francesco

made with methods described in the second treatise. These are the plan di Giorgio began to develop his geometrical methods and make the

of a basilica on the human form on fol. llv, and the diagrammatic drawings for his first treatise probably around 1470. A few of the plans

scheme for a faSade, also on the human form, on fol. 21v. Conversely, for churches in Saluzzianus 148 appear in a copy of an early draft of

only one of the methods described in Magliabecchianus II.I.141 was the first treatise in the Zichy Codex in Budapest; see C. Kolb, "The

not used for drawings in the first treatise, and that is the elaborate method Francesco di Giorgio Material in the Zichy Codex," JSAH, XLVII,

for designing the cross section of a domed church on fol. 41. There are 1988, 132-159.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 11

that are quite different from those of late medieval architecture

and this gave him grounds to claim his methods as his own

inventions. His theory prescribes that forms, proportions, and

structure for a given building should be designed by a single,

dt. M >- wl Vffi *d 1?r;H * *?A a WIUt* , . ^,H??

integrated procedure.

s^ <2^^^-t~T-S VX & a- w lW- <^< A4U^1,,^

In three of his diagrams, on folios 41 and 41v in Magliabec-

54 tv'n?e5.cjwe s- P W rs J.i*r e^

J#llo t ?pelpn 1al rkV X ol ?I chiLpl?~ A b? GF c1~u?aE?~. chianus II.I.141, Francesco di Giorgio uses a circular arc and its

^I o .^l *? f-*dtet- e ^le.< *:ure ca Sr AS-6*<,^i chord to generate a subtended segment of radius, which he calls

St

^^e,je}f *T74il!>w^

^^ ? *(^tyt^ 16 ^1^^'^i1^'3^

t^?F ;%1*fi* ' r ,<l1WA w a "module" for the whole building, but he does not say what

ag^^n i*^^M^r.'LW.^^?llf^ ^r)T>^\dS^n*Jn ^ C

the module measures or how to use it.22 For example, he de-

scribes the upper right-hand drawing of folio 41v (Fig. 5) by

the following paragraph:

If the temple should be oblong [and] faceted or round, to give it

proper height and [to ensure] that it should have proportionable

correspondence to the width, first a square is formed of equal sides

which is divided into four parts. Then two lines are drawn from

corner to corner, and two other lines that touch all the four divisions

:!X C

of the square, namely TSVX.23 And [extensions of lines TV and SX]

t,

make another square of angle ZD and it is divided into four parts

like the large square. And in the center line at point Q is drawn a

A . :-- --- '. ' " ' '' - .r.S

semicircle that will make a portion of a circle between the lines [TX

'T. /T f rej; dMe xc^t?t^.^.Uw^ ^ H

.,t. a,. ~*, Jpor .N.r_~v K. ^S. ?l SSC.~t.* and VS], in the middle of which portion is drawn a line from point

- -,.:,

:'5\ ' 1? .~-S. -~,~ ^ K.tl~ ^, w,l**,.,, -- Q to G called AB. And this portion will be the module for the whole

/' X \ Jl ? *<S i^ui4 <A;L *(W;?<M Ann *x ^ll x je'^?M<h 'M n l*Xi

V / XK!/ jllW 4^ w -fr w * l<?^ c W Sm^ lMtt<l <4NA t l building,

a HT -0 with which is divided the diagonal line, and as many parts

as :1

:4 -yit ?.t.> <U- ^w1 * N A-M eZ^A-- S W * is found

o to be the portions of this line, so many is given to the

' -*m f.w..r FT* S t. ,,,^-h ,-^ ?>, Pf;F height, always adding one part more. Then it will have just height

qf^- sitw .Yw?A? -pfAtkr: kJ-4L .. r~Sowo.%.U; e s?<r.2l<,?SU^^lwi^.A<

i^ r e ? wr W-^ -; S^4;e,lt s ol g-0v. L- to width, following the order of the present figure.24

von der Fialen Gerechtigkeit, Faksimile der Originalausgabe Regensburg 1486,

ed. F. Geldner, Wiesbaden, 1965; L. R. Shelby and R. Mark, "Late

Gothic Structural Design in the 'Instructions' of Lorenz Lechler," Ar-

chitectura, IX, 1979, 113-131; Mainstone, "Structural Theory and De-

sign before 1742," 303-310; and Sanabria, "The Mechanization of

Fig. 5. Francesco di Giorgio, geometrical method for designing a church.

Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. ex-Magliabecchianus Design in the Sixteenth Century," 281-293. The methods of Rodrigo

II.I.141, fol. 41v, c. 1490-1492. Ink on paper (Biblioteca Nazionale, Gil, as described by Sanabria, address the problems of sizing piers and

Florence). buttresses, but they are not the methods of Francesco di Giorgio, which

means that there was more than one tradition of structural design among

Procedures of this kind were well known to architects of the medieval masons.

Middle Ages, and although we are poorly informed about their 22. Cf. Francesco di Giorgio, Trattati, ed. Maltese, II, pls. 233-234,

and 399-401. The procedure on fol. 41, describing the cross section of

methods, there is some reason to believe that they used elements

a church with aisles and dome, was first published in 1572 by Philibert

of quadrature to calculate the dimensions of structural forms, Delorme in his Architecture; he did not, of course, acknowledge his

source.

including piers and buttresses.21 Francesco di Giorgio's treatises

23. There is a small discrepancy between text and

contain a large inventory of quadrature procedures, perhaps the

point marked D in the upper left side of the drawing

most complete we shall ever have, but we may not recognize point T in the text. In the next line of text the lett

them as such because he adapted them to forms and proportions another point at the bottom of the drawing. Thus it a

error is in the drawing. The point marked D in the up

21. Quadrature was one of the well-kept secrets of the medieval drawing should be marked T, as it is in my Fig. 6.

masons. Villard de Honnecourt knew it as a method of design, although 24. Magliabecchianus II.I.141, fols. 41-41v: "Sia il tem

perhaps not of structural design; see H. R. Hahnloser, Villard de Hon- facciato o tondo per darli debita alteza et che alla largh

necourt: Kritische Ausgabe des Bauhiittenbuches ms. fr. 19093 der Pariser abilmente abbi conrispondentia formisi inprima uno qu

Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, 1935, pl. 39. There are no known written lati ilquale Sia quadripartito Dipoi sitiri due linee [fol

descriptions of quadrature or of any technique of structural design that ad angulo et due altre linee che tochino tuctti & Quatro

predate the treatises of Francesco di Giorgio. For quadrature and other Quadro Cioe TSVX & faccino unaltro quadrato fuore

aspects of late medieval design theory, see L. R. Shelby, Gothic Design & sia Quadripartito come ilmagior quadrato & nella linea

Techniques: The Fifteenth-Century Design Booklets of Mathes Roriczer and Q Sitiri uno Semicirculo che in fra lelinee fara portion

Hanns Schmuttermayer, Carbondale, Ill., 1977; M. Roriczer, Das Biichlein mezo della qual portione sitiri una linea dal ponto Q al

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

i I tq . - *I * I- ^> I "

t

c

'i 11 f iD d 1; P _ i

TX r,po _ _

T

eVt* I C s

a^^"t: ,:.

G

( _r I*

Fig. 6. Francesco di Giorgio, geometrical method for designing a church.

Magliabecchianus II.I.141, fol. 41v. Redrawn with proportional analysis

Fig. 7. Francesco di Giorgio, plan for an ideal church. Turin, Biblioteca

(author).

Reale, ms. Saluzzianus 148, fol. lv, c. 1475-1476. Ink on parchment

(Biblioteca Reale, Turin).

Text and drawing correspond exactly, except for one small

error of labeling when he used the letter D twice in the diagram. the baseline ZD. Francesco di Giorgio does not specify the

But if the text tells us how to make the drawing point by point, dimensions of this rectangle, but its short side equals the "mod-

it does not explain to what the points refer. Francesco di Giorgio ule," the line segment AB. Study of this drawing shows that

says that you divide the diagonal line with the module AB and the height of the church is made from an apparently arbitrary

give so many parts to the height of the church, always adding mixture of modules, five of one kind plus one of another.

one part more. AB divides the diagonal QG by approximately The large unlabeled square with which this procedure begins

4.8, or 5 when rounded up to the nearest integer. The "part" also appears to be arbitrary, for it serves no real purpose in the

making up the height is not AB, obviously, but a small square stated procedure. Its presence is all the more curious when we

that is one-fourth of the square VXDZ (Fig. 6). Five of the realize that the very next paragraph and drawing of folio 41v

small squares measure the height of the diagram, from the base- describe essentially the same procedure for obtaining the height

line ZD to the apex of the large square. We still have to add of a church, without the large square and without adding dif-

"one part more," and that appears to be the rectangle below ferent modules.25 For the upper drawing on folio 41v, there is

Et questa portione sara modulo actuctto lo edifizio conla quale Siparti 25. Magliabecchianus II.1.141, fol. 41v: "And wanting to imitate the

lalinea diagonia et quante parti sitroverra essa linea di Portioni tanto in same form, two connected squares of equal faces is made. A line called

nella alteza sidara agiongendo sempre una parte piu allora hara iusta CD is drawn through the middle of both, and in the middle of this, a

alteza alla largheza Seguendo lordine della presente figura." semicircle is drawn [with its center] at point N and from V to K. Then

Cf. Francesco di Giorgio, Trattati, ed. Maltese, II, 401. Maltese's from the end of the semicircle terminated [at] K, a diagonal line is

transcriptions of both treatises are unreliable because they were exten- moved, passing through the intersection of the center line to the end

sively altered for the sake of partially modernized spelling and punc- of the angle X, which line makes a portion of the circle lined [sic] from

tuation. The above translation and the transcription are my own. The N to T, of which OS is taken, which width will be the module for the

transcription reproduces Francesco di Giorgio's text exactly except for whole temple, of which 5 parts is given to the center line from point

expanded abbreviations and ligatures. Francesco di Giorgio's prose im- N [to] A. And this will be the height of the whole, terminated by the

proved greatly between his first and second treatises, but it was never transverse line BF, so that it will make 7 parts in its diameter, as [in]

quite perfect. The text of Magliabecchianus II.I.141 has very little punc- the figure. And this can also be taken from the top of the semicircle

tuation and capitalization, its orthography is archaic and sometimes [at] Q its height descending along the center line to the baseline [at]

irregular, and words are often run together. The grammatical errors D." (Et per volere la medesima forma inmitare faccinsi due conexi quadri

that appear in my translation are those of Francesco di Giorgio. I have dequali faccie tirata una linea perlo meso danbe due Sengniata CD et

endeavored to translate his text in such a way as to convey the quality nel mezo dessa alponto N & dal V al K Sitiri uno Semicirchulo Dapoi

of his prose as well as its meaning. dalla estremita del Semicirchulo terminato K Simuovi una linea di-

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 f on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 13

i ,, , ..... . ?. ? ..

- . ?..?..::-'

.. iT.. ?

,S.:.:,. ,. i--:

- : .- / -

.......T

......../..... / ''~~ ' \ 4'~`

G

4 I 'D

>2

. X.

.

. .. .. :,

... . ;

. , ' ' j:.. . . . . .

V

z D

Fig. 8. Francesco di Giorgio, geometrical method for designing a church, Fig. 9. Francesco di Giorgio, geometrical method for designing a church,

superimposed on a plan for an ideal church, step 1 (author). superimposed on a plan for an ideal church, step 2 (author).

a discrepancy between text and image that is more than a mis- When the width of the descending square, VXDZ, is set to the

taken label. The unexplained larger square makes the drawing span of the nave, the square TSXV aligns with the crossing,

resemble a plan more than a cross-sectional elevation of a church, and the lateral apices of the large square align with the end

and that is probably what the procedure is meant to be. When walls of the transept. Francesco di Giorgio's theory encourages

Francesco di Giorgio refers to the height of the church in this variations in the use of his methods, so if we add another square

context, he is referring to the height of the drawing representing of the same size to VXDZ we obtain the full length of the nave

the length of the church. To judge from their appearance, the (Fig. 9). The resulting overall length of the church equals seven

drawings on folio 41v describe correlated methods for designing of the smaller squares, an approved proportion in Francesco di

both the plan and the elevation of a church. This seems plausible Giorgio's theory, and the one he seems to have preferred.27 The

because the upper diagram closely fits one of the plans in Sa- new baseline of the diagram now reaches to the middle of the

luzzianus 148 (Fig. 7). faSade wall, and the apex lies at the centerline of the wall at

Figure 8 shows the diagram of Magliabecchianus II.1.141,

folio 41v, drawn over a plan on folio lv in Saluzzianus 148.26

the drawings in Saluzzianus 148. They were not constructed on the

folios but were copied, in my opinion by Francesco di Giorgio himself,

from notebooks in which he made drawings at the scale intended for

aghonia passante perla intersecazione della linea media insino alla ex- the parchment manuscript. He used a compass to transfer dimensions

tremita dellangulo X la quale linea fara una portione di circulo lineato and draw circles, and a ruler for the straight lines. The resulting drawings

dal N al T della quale sipigli OS Laquale latitudine sara modulo actuctto appear to be precise, but they are all slightly asymmetrical. Conse-

iltempio Deleq[u]ali senedia parti 5 alla linea media dal ponto NA et quently, a precisely drawn geometrical procedure will not fit exactly

Questa Sara lalteza del tuctto terminata La transversa linea BF siche fara onto both sides of a plan. I assume that the procedure explains the plan

parti vii insuo diamitro come la figura et questa Sipuo ancho pigliare if I can obtain precise correlation with respect to one side of a drawing

dal sommo del Semicirculo Q La Sua alteza discendendo perla linea and approximate correlation on the other side.

media infino allinbasamento D.) Cf. Francesco di Giorgio, Trattati, ed. 27. Believing that he was following the theory of Vitruvius, Fran-

Maltese, II, 401. cesco di Giorgio correlated the proportions of plans with the human

26. Cf. Francesco di Giorgio, Trattati, ed. Maltese, I, figs. 18 and form. Various of the orders, according to Vitruvius, were first made to

256. The plan in question is at the center of the bottom margin of the imitate the forms of men and women who were six, seven, and eight

folio, in a group of three plans. It is captioned "Tenpio acrociera essenza heads tall, and then they were made higher, with the Corinthian reach-

navi" (Temple with crossing and without aisles), and its crossing is ing a proportion of 10:1. Francesco di Giorgio allowed for all of these

labeled "chuppola hover trebuna" (dome or tribune). Graphic analysis proportions in plans and elevations as well as in columns, and he added

of Francesco di Giorgio's plans must take account of irregularities in 5:1 for good measure. In his columns as in his plans, he preferred 7:1.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

Fig. 11. Quadrature series drawn on a project for an ideal church by

Fig. 10. Quadrature series drawn on a project for an ideal church by

Francesco di Giorgio, step 2 (author).

Francesco di Giorgio, step 1 (author).

by one step, the resulting segment A'B' exactly equals the thick-

the other end of the church. The line segment AB, which

ness of the walls (Fig. 11). This shows that Francesco di Giorgio

Francesco di Giorgio says is the "module" for the whole build-

added a safety factor to his design by deriving his wall thickness

ing, measures the thickness of the walls. With this, we at

canone step up in the quadrature series based on the span of the

nave. He must have done this because in the mid-1470s, when

understand why his procedure specifies the addition of one mod-

he made the drawings of Saluzzianus 148, his ideas were still

ule to the plan. When proportions are determined by a geo-

metrical method using points, lines, and planes that have no

untested. His first opportunity to test his theory for barrel vaults

thickness, structural walls must detract from the ideal. Francesco

carried by walls came in 1483, with a commission to build a

di Giorgio effected a compromise by adding one thickness of dedicated to San Bernardino at the monastery of the

church

wall to his plan, and by dividing that thickness betweenZoccolanti

the just outside Urbino (Figs. 12 and 13).

two end walls. San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti was begun soon after Fed-

Analysis of the drawing on folio 1 lv in Saluzzianus 148 shows erico da Montefeltro died, a melancholy substitute for the gran-

that Francesco di Giorgio's procedure for deriving the module diose mausoleum Francesco di Giorgio had designed for his great

AB is in fact a geometrical method of structural calculation patron.28 In its original state San Bernardino had a barrel-vaulted

based on the span of the vault. The method is a variant of nave without aisles and a domed transept with three hemicycles.

quadrature, since the line segment AB is equal to one-half the

difference between the sides of the inner and outer squares in 28. The only documents for San Bernardino are scattered records of

a two-step quadrature series. The walls could be made thicker payments and donations in the 1480s; cf. L. Serra, "Nota sulla chiesa

simply by performing the procedure at one or more steps up in di S. Bernardino ad Urbino," Rassegna Marchigiana, X, 1932, 247-257;

P. Rotondi, "Quando fu costruita la chiesa di San Bernardino in Ur-

the quadrature series, and Francesco di Giorgio did that, too.

bino," Belle arti, 1947, 191-202; Fehring, "Studien uber die Kirchen-

The plan of the "Tenpio di tre quadri in nel chorpo.. ." in bauten des Francesco di Giorgios," 82-108; and G. Volpe, Francesco di

Saluzzianus 148 gives some insight into his thinking on this Giorgio: Architettura nel ducato di Urbino (Stella Polare Guide di Archi-

tettura, 10), Milan, 1991, 28-31. The little church has been attributed

point (Fig. 4). A quadrature series drawn on the clear span of

to a number of other architects, including Bramante, but its documen-

the nave produces a line segment AB that is considerably less tation, though sparse, leaves little doubt that it was built when Francesco

than the thickness of the walls (Fig. 10). If we expand the series di Giorgio was ducal architect and so it should be attributed to him.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 15

- C-

~co

Fig. 12. Francesco di Giorgio, San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti, Urbino,

c. 1483-1489. Nave (author).

The great Montefeltro altarpiece of Piero della Francesca stood crn

upon its high altar. Sometime in the 1560s, the apse was re-

Fig. 13. San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti. Plan (author, after Papini).

moved and replaced by an extended monk's choir. The follow-

ing analysis depends upon a reconstruction of the original plan

walls,

of San Bernardino based on a plan published by Roberto just as he had in the drawing in Saluzzianus 148, by going

Papini.29

When the method of Magliabecchianus II.I.141, folio 41v,

up one step in the quadrature series to generate the module (Fig.

15). This

is drawn on the plan of San Bernardino, with the width oflarger

the module can be obtained by drawing the in-

scribed

descending square set to the span of the nave vaults, circle in the larger square, or it can be obtained more

it appears

readily bybut

that the module AB measures the walls of the hemicycles rotating that larger square by 45? as in Figure 15.

not the walls of the nave, which are considerably thicker

The latter (Fig.

is the more likely method since it generates the form

14).30 Francesco di Giorgio added a safety factor to the

of the naveas well as the thickness of the walls.

transept

Francesco di Giorgio used a similar method to add a safety

factor to the thickness of his walls in the second of his barrel-

29. A drawing of the interior showing the original apse is in a scrap-

vaulted now

book of architectural drawings, probably assembled by Vasari, churches,

in Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio in Cor-

the Biblioteca Laurenziana, ms. Ashburnham app. 1928; see H. Burns,

"Progetti di Francesco di Giorgio per i conventi di San Bernardino e

Santa Chiara di Urbino," in Studi Bramanteschi, 293-312. For a recon-

of the

struction of the original plan, see Papini, Francesco di Giorgio, church was blocked on two of its sides by monastery walls and

architetto,

III, pi. 6. a hillside, and on the other two sides by a steeply descending slope with

30. The square does not reach to the front wall of the nave, the loose soil. To use as much of the site as he did, Francesco di Giorgio

length of which does not correspond to any rational multiple or fraction had to add large splayed buttresses toward the weak edge of the hill

of the base square. The nave of San Bernardino is ill-proportioned even though they make the facade asymmetrical. In the second sentence

according to Francesco di Giorgio's theory, but its proportions were of his first treatise, before he says anything at all about proportions, he

partly determined by its site, which is restricted and difficult. Extension instructs architects to pay attention to the site above all else.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

Fig. 15. San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti. Plan with diagram from

Fig. 14. San Bernardino degli Zoccolanti. Plan with diagram from

Magliabecchianus II.I.141, fol. 41v, step 1 (author). Magliabecchianus II.1.141, fol. 41v, step 2 (author).

San Bernardino in Urbino and Santa Maria delle Grazie al

tona, begun in 1484 (Fig. 16).31 Figure 17 shows that the thick-

ness of the walls corresponds to the module generated by Calcinaio

the in Cortona allow us to observe a Renaissance architect

superior step in a quadrature series based on the span of testing

the his own theory of structural design for a new and un-

nave.32 The resulting walls are 2.25 meters thick for vaults

familiar type of vault. Francesco di Giorgio took his responsi-

spanning 11.7 meters. Their thickness is readily visible in bilities

the as a structural designer very seriously, and he was cau-

tious. His designs were profoundly innovative, but still he had

splayed windows of the clerestory and gives the impression that

not developed a theory of structural design for barrel vaults to

the church was enormously overbuilt. It probably was overbuilt

because it was a daring experiment for Francesco di Giorgio,the

a point where Bramante could use it to design Saint Peter's,

where the vaults would have more than twice the span of the

church nearly twice the size of San Bernardino of the year

before.33 vaults in Cortona and the spaces would be formed by complex

piers rather than simple walls.

31. The church was built to house a miracle-working image of the The next step in the development of Renaissance vaults, lead-

Madonna on the wall of a lime pit (calcinaio) on the hill below Cortona.

ing toward Saint Peter's, can be found in Leonardo da Vinci's

For the documents, see Weller, Francesco di Giorgio, 15-16, docs. XLII-

XLVII. Measured drawings were published in Papini, Francesco di Gior- projects for domed churches in Manuscript B, usually dated

gio, architetto, III, pls. LV-LXI. A complete set of measured drawings, 1487-1490.34 They include plans, perspective views, and sec-

made during restoration in the 1970s, has been published in P. Ma-

tracchi, La chiesa di Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio presso Cortona e

l'opera di Francesco di Giorgio, Cortona, 1991. 34. Manuscript B includes both the codex with that signature in the

32. In this case the overall form was generated by a grid such as Institut de France and another manuscript that was once joined to it,

those on fol. 42v in Magliabecchianus II.I.141. Cf. H. Millon, "The also in Paris, ms. 2037 in the Bibliotheque national. Facsimiles of both

Architectural Theory of Francesco di Giorgio," Art Bulletin, XL, 1958, have been published. Cf. C. Ravaisson-Mollien, Les manuscrits de Leonard

257-261. Millon argued that the plan of the church in Cortona was de Vinci de la Bibliotheque de l'Institut, publies par Charles Ravaisson-Mollien,

based on the upper drawing on fol. 42v, but it more closely resembles Paris, 1881-1891, 6 vols.; and Leonardo da Vinci, II Codice B nell'Istituto

the lower plan on that same folio. di Francia, ed. E. Carusi, R. Marcolongo, and M. Pelaez (I manoscritti

33. The span of San Bernardino, according to Papini's plan, is 6.3 e i disegni di Leonardo da Vinci pubblicata dalla Reale Commissione

meters, and the walls are 1.35 meters thick. Vinciana sotto gli auspici del Ministero dell'Educazione Nazionale, 5),

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 17

Fig. 16. Francesco di Giorgio, Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio,

Cortona, 1484-1490. Nave (author). Fig. 17. Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio. Plan with quadra

series superimposed (author).

tions showing various combinations of architectural elements

composed according to several different geometricalbeen stimulated by the failure, in 1490, of his project for

methods.

Leonardo clearly intended to focus on the composition

tiburioof

ofa Milan cathedral, for which he had wanted to pr

a dome al-

domed church as a single problem in architectural theory, on a drum. He may also have been stimulated by co

with

though his reasons for doing so remain obscure.35 He mayFrancesco

have di Giorgio in the summer of 1490. He m

have gained access to a copy of Francesco di Giorgio's f

Rome, 1941. A few other drawings of domed churches by Leonardo

are in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, in the Codex Trivul-

zianus, and in the Codex Atlanticus. For a complete list of the drawings

he attempted

and illustrations, see L. H. Heydenreich, Die Sakralbau-Studien Leonardo to reconstruct its outline, assuming that Leonardo's in

in the

da Vincis, Engelsdorf, 1929; 2d ed., Munich, 1971. The earliest subject was largely theoretical and not practical. S. Lang, "L

datable

item in Manuscript B was entered in 1482 and the latestardo's Architectural

in 1492; see Designs and the Sforza Mausoleum,"Journal o

Warburg

C. Pedretti, "The Missing Folio 3 of MS B," Raccolta Vinciana, and Courtauld Institutes, XXXI, 1968, 218-233, took th

XX,

1964, 211-224. None of the drawings of central-plan posite

churches inof view, arguing that Leonardo's architectural studies

point

always

Manuscript B is dated. Most scholars of Leonardo date them rooted in opportunities for real commissions, even thoug

to 1487-

1490, although Heydenreich thought some entries might was usually

be as late asfrustrated in his pursuit of them. In the preface to the s

1495. In my opinion, the drawings of churches appear to (1971)

haveedition

been of the Sakralbau-Studien, Heydenreich brusquely

misses

made in a burst of creative energy during a relatively short Lang's

period of thesis and all attempts to reconstruct a putative arc

tural

time lasting a few months or even a few weeks. For reasons oeuvre for Leonardo. His view has been widely accepted, bu

explained

my opinion Lang's arguments are not without merit. The questio

below, I would place that period in late 1490 or early 1491.

35. Heydenreich, Sakralbau-Studien, 77-84, believed thatwhether Leonardo planned to write a treatise on architecture mig

the draw-

reopened.

ings of Manuscript B were intended for a treatise on architecture, and

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

Fig. 18. Leonardo da Vinci, projects for domed churches, c. 1490. Paris,

Fig. 19. Leonardo da Vinci, project for a domed church, c. 1490. Paris,

Institut de France, Manuscript B, fol. 17v (from Carusi, Marcolongo,Institut de France, Manuscript B, fol. 18 (from Carusi, Marcolongo,

and Pelaez, eds., II Codice B nell'Istituto di Francia, 1941). and Pelaez, It Codice B nell'Istituto di Francia).

treatise at about the same time, because its influence is clearplans

in with spaces centered on domes.37 Some of his plans are

Manuscript B.36 little more than diagrams, and in others the structural forms are

One of Francesco di Giorgio's innovations in architectural

only roughly indicated and appear to be purely arbitrary. In the

projects that he chose to delineate most carefully, Leonardo

theory was to use drawings to study systematically the possi-

created structural forms by filling in the gaps between the lines

bilities of formal composition in a given building type, and this

is nowhere more evident than in the book on temples in Sa-

that define the spaces in plan, and then he studied the resulting

luzzianus 148. In Manuscript B, Leonardo picked up the prob-

37. Leonardo did not use any of the geometrical procedures of Fran-

lem of church design where Francesco di Giorgio had left it

cesco di Giorgio's second treatise, including the method for calculating

and continued the process of exploration, concentrating on domed

a structural module. He seems not to have had access to the second

churches. He used a variety of geometrical procedures to create

treatise until 1501, when he went to Urbino in the company of Rodrigo

Borgia. He then copied parts of the second treatise into one of the

recently rediscovered Madrid codices; see Leonardo da Vinci, The Madrid

Codices, New York, 1974; and L. H. Heydenreich, "Bemerkungen zu

36. Leonardo owned and annotated a copy of the first treatise, now

den wiedergefundenen Manuskripten Leonardo da Vincis in Madrid,"

in Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, ms. Ashburnham 361. For a fac-

Kunstchronik, XI, pt. 4, 1968, 92-96. Marani, "Leonardo, Francesco di

simile of and commentary on this manuscript, see Francesco di Giorgio

Giorgio, e il tiburio," 81-92, has argued that Francesco di Giorgio

Martini, Trattato, ed. Marani. Leonardo's marginal annotations are very

brief and have little to do with the content of the treatise. Maraniintroduced

is geometrical procedures into his second treatise under the

influence of Leonardo, and I once shared that opinion. I now know,

certain that the annotations postdate 1500, but that may not correspond

however, that most of those procedures were invented by Francesco di

to the date when Leonardo acquired the manuscript. The most striking

Giorgio himself some twenty years before he saw Leonardo in Milan.

evidence of its influence on Leonardo's thinking is his famous drawing

Since Leonardo did not use the procedures in 1490, their invention

of so-called Vitruvian man in the Accademia in Venice. This drawing,

cannot be attributed to him. Obviously, Francesco di Giorgio did not

usually dated to c. 1490, is clearly based on Francesco di Giorgio's

tell all when he and Leonardo met in 1490, so Leonardo was left to

drawing of the same subject in Saluzzianus 148, fol. 6v, and Ashburnham

361, fol. 5. invent his own methods of design, which he did.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BETTS: STRUCTURAL INNOVATION AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN 19

Fig. 21.

Fig. 20. Graphic analysis of Leonardo's Manuscript B, Graphic analysis

fol. 18, stepof Leonardo's

1 Manuscript B, fol. 18, step 2

(author). (author).

forms in three-dimensional sections and perspective views (Figs. nardo brought Renaissance theory to the point where Bramante

18 and 19). could use it to design the new Saint Peter's.39

For example, the plan on folio 18 (Fig. 19) is based on a pair Bramante's design for Saint Peter's went through several stages

of concentric circles centered on the dome, the inner circle being of revision before Julius II laid the foundation stone of the

two-thirds of the diameter of the outer circle (Fig. 20). This is northwestern pier with proper ceremony on 18 April 1506.

one of the proportions that Francesco di Giorgio recommends Two preliminary projects are known from drawings made dur-

for round churches in his first treatise.38 But while Francesco di ing the period of Bramante's tenure as capomaestro at Saint Pe-

Giorgio simply made plans out of concentric circles and poly- ter's. The most important of the drawings are in the Uffizi in

gons, Leonardo used the figure as the starting point for a more Florence (Figs. 23 and 24). Together Uffizi 1A and Uffizi 20A

complex geometry. He drew the orthogonal and diagonal radii

and located the centers of the chapels where the radii intersect 39. From the point of view of Francesco di Giorgio's theory, the

the outer large circle (Fig. 21). The chapels are formed by small projects of Manuscript B are deficient because they do not involve

calculation of structural dimensions based on the spans of vaults. In

circles whose radii equal the difference between the two large 1490 Leonardo was apparently unaware that such calculations could be

circles. The outer perimeter of the building is made by drawing incorporated in geometrical procedures of design. Eventually, after 1500,

a square tangent to the circles of the chapels (Fig. 22). To form he speculated about the behavior of structures from the point of view

of Archimedean mechanics, of which he was a keen student. See A.

the structure, Leonardo simply filled in the gaps between the Chastel, "The Problem of Leonardo's Architecture in the Context of

circles and added walls to the outside and inside. He thereby His Scientific Theories," in Galuzzi, ed., Leonardo da Vinci: Engineer and

reinvented the ancient Roman method of using complex pier Architect, 193-206; C. A. Truesdell, "Fundamental Mechanics in the

Madrid Codices," in Bellone and Rossi, eds., Leonardo e l'etd della ragione,

forms in concrete construction as a means to solve the design

309-319; M. Clagget, "Leonardo da Vinci: Mechanics," in Dictionary

problems invoked by the Renaissance dome. With this, Leo- of Scientific Biography, 15 vols., New York, 1973, VIII, 215-234; C.

Zammattio, "Mechanics of Water and Stone," in L. Reti, ed., The

Unknown Leonardo, New York, 1974, 190-215. Though his results were

not immediately useful for purposes of architectural design, Leonardo's

38. Cf. Saluzzianus 148, fol. 13: "He tenpi circhulari hovero tondi investigations anticipate modern structural mechanics. In at least one

preso el diamitro disua larghezza laterza parte desso dentro efuore Edop- instance his intuition is startling. In Madrid ms. I, fol. 143r, is an

po queste circhular terminationi inellultimo cinto difuore lechonpartite isometric view of a barrel vault carried by massive walls. The walls are

cholonne auna auna chollocharai hovero adue adue Cholle medexime marked by diagonal lines representing the force exerted by the vault.

mixure epartitioni Elsimile dala parte didrento hordinato sia." (And These are not the catenary curves described in the modem theory of

circular or round temples: take the diameter of its width, the third part the arch, but they clearly indicate Leonardo's understanding of structural

of it outside and inside. And after these circular terminations you will design in vaulted masonry as a three-dimensional problem. The thick-

put the compartmented columns in the last circle outside, one by one ness of the walls must be governed by the height and volume of the

or two by two. With the same measures and partitions. And the same vault as well as by its span. The essential weakness of Francesco di

is ordered on the inside part.) Giorgio's theory is that it is entirely two-dimensional.

This content downloaded from

95.249.247.83 on Fri, 11 Dec 2020 20:07:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 JSAH, LII:1, MARCH 1993

Project" (Fig. 25).40 More recently, Graf Metternich tried to

dimension this project by assuming that it would be built on

the existing walls of the choir of Nicholas V. But Uffizi 1A has

no dimensions or any indications of the context and existing

structures at the site, so we must suppose that it was made to

demonstrate what Bramante could do on a clean site if he were

not constrained by considerations of function, if he had a free

40. See Geymiiller, Die urspriiglichen Entwiirfe. Since 1875, the lit-

erature on Bramante's Saint Peter's has grown enormously, and it is

contentious. For a review of literature up to 1969, see A. Bruschi,

Bramante architetto, Bari, 1969, 532-592, 883-908. The most extensive

recent studies of Saint Peter's are by the late Count Metternich and his

colleagues at the Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome. See F. Graf Wolff

Metternich, Die Erbauung der Peterskirche zu Rom im 16. Jahrhundert.

Erster Teil (Rimische Forschungen der Bibliotheca Hertziana, 20), Vi-

enna, 1972; idem, Bramante und St. Peter, Munich, 1975; C. L. Frommel,

"Die Peterskirche unter Papst Julius II. in Licht neuer Dokumente,"

RomischesJahrbuchfu'r Kunstgeschichte, XVI, 1976, 57-136; C. Thoenes,

"Erste Skizzen: St. Peter," Daidalos, V, 1982, 81-92; F. Graf Wolff

Metternich

Fig. 22. Graphic analysis of Leonardo's Manuscript B, fol. 18, step 3 and C. Thoenes, Diefriihen St.-Peter-Entwirfe, 1505-1514

(author). (Romische Forschungen der Bibliotheca Hertziana, 25), Tiibingen, 1987;

C. L. Frommel, "Il cantiere di San Pietro prima di Michelangelo," in

A. Chastel and J. Guillaume, eds., Les chantiers de la Renaissance, Paris,

1991, 175-190.

show us how Bramante applied the theory of the fifteenth cen- Somewhat different opinions have been expressed by H. Giinther,

tury to the task of designing a structure that he and his client "Werke Bramantes im Spiegel einer Gruppe von Zeichnungen der

Uffizien in Florenz," MiinchnerJahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, XXXIII,

surely knew would point the way toward the future of a new