Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Goldstein 18

Uploaded by

Lester Moe0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesOriginal Title

goldstein18

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesGoldstein 18

Uploaded by

Lester MoeCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Burns, in his discussion of motivations for orthodontic treatment,

cites the results of a study by Jarabak who determined

five stimuli that may move a patient toward orthodontia.

The motives, also applicable to esthetic dentistry, are as follows:

(1) social acceptance, (2) fear, (3) intellectual acceptance, (4)

personal pride, and (5) biological benefits. (It should be noted

that these stimuli pertain only to patients who cooperate in

treatment.)6,19

A spirit of cooperation and understanding between you and

your patient is paramount to successful esthetic treatment.

This relationship is a kind of symbiosis in which each contributes

to the attitude of the other. The necessity for close observation

and response on your part, particularly to nonverbal

clues offered by the patient, cannot be overemphasized. The

confidence generated by a careful and observant dentist will

be perceived by the patient; so, unfortunately, will a lack of

confidence. A competent, confident, professional dentist can

reinforce the positive side of the ambivalence that patients feel

toward persons who can help them but who they fear may

hurt them.

Much psychological theory in dental esthetics must be formulated

through analogy because of the comparatively recent recognition

of the importance of dental esthetics and the consequent

lack of a comprehensive database. The most obvious parallel

field is plastic surgery. In a pioneering paper published in 1939,

Baker and Smith21 posited a system that categorized 312 patients

into three groups based on personality traits as they related to a

desire for corrective surgery, the motives for requesting it, and

the prognosis for successful treatment.

●● Group I—Ideal individuals for successful treatment with

well‐adjusted personalities, moderate success in life, aware

that all life problems cannot be solved by better‐looking

teeth, and realistically want treatment to improve esthetics

and/or for greater comfort. In your own practice, patients

who fall into the first group are moderately successful people

who want repair of their disfigurements for cosmetic reasons

or comfort, not as an answer to all their problems. They do

not expect too much from the improvement and they have a

realistic visual concept of the outcome. They are ideal subjects

for successful treatment.

●● Group II—Irksome individuals of two types. The very irksome

type are individuals who remain unhappy with results

despite the excellent technical outcome achieved through

prior treatment, indicating the same will happen with future

treatments. Underlying that unhappiness, they continue past

dysfunctional thinking about their prior appearance defects

causing unrelated life problems outside the oral cavity or

they find actual life with better‐looking teeth to be not as

great as they had earlier unrealistically fantasized. A substantially

less irksome type in this Group II category are passive

apologetic individuals who are grateful for any and all

treatment,

even though past results proved technically unsatisfactory

as likely will be results of future treatments.

●● Group III—Individuals with psychotic personalities for

whom treatment outcomes will never be satisfactory in their

view, regardless of actual technical results. Their visibly

unattractive

dental esthetics that existed before treatment

served then as a focal point of their life problems and will

probably continue always. With these people, any esthetic

correction serves only to disrupt the rationalization process.

Soon, some other defect is seized upon as the focus for their

continuing psychotic delusions. These individuals warrant

other professional treatment such as psychological or psychiatric

counseling because dental treatment alone likely only

disrupts their delusional rationalizations with no significant

benefit in the longer term.

As expressed above, patients focused on cosmetic dentistry can

be greatly appreciative and/or greatly demanding. Nevertheless,

they must all be satisfied with their results. This satisfaction usually

means their concept of a natural looking outcome that meets

their pretreatment expectations and receives “a thumbs up”

approval in the eyes of the patient and the most significant

other(s) in the patient’s life. Advance measures, pretreatment, by

the dentist to improve the likelihood of posttreatment satisfaction

include the following:

●● Listen well to the wants and perspectives of the patient before

embarking on treatment. This “listening” extends to observing

well any possible pertinent nonverbal clues exhibited by

the patient.

●● Discuss well any concerns, questions, expectations, and as

much or little detail as appropriate for the individual patient.

●● Present treatment options along with their procedures,

timelines,

advantages, and disadvantages or limitations.

●● Be “realistically idealistic,” expressing the ideal but realistic

scenario while being neither unrealistically optimistic that

then builds too high of expectations that cannot be met and

will generate dissatisfaction. Nor should you be unreasonably

pessimistic. The latter balances lower expectations

that results will nearly always meet and exceed and for that

reason will nearly always generate substantial satisfaction

with positive word‐of‐mouth evaluative comments to family

and friends.

●● Trial smile procedures are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

The dentist–patient relationship should be long term, which by

definition concerns posttreatment. Esthetic dentistry offers this

opportunity more so than other dental treatments. Patients typically

deliberate over this decision longer and with more thought

invested than for other dental treatments. This greater investment

in the decision process combined with improvement of

appearance/physical attractiveness, as well as dental health, sets

the stage for a rather special bonding consequence analogous to

that between a cosmetic surgeon and a patient. To increase this

likelihood, just as there are pretreatment alerts and actions for

dentists when delivering esthetic treatments, there are posttreatment

alerts and actions. For patients satisfied with their results,

reinforcing words and careful direction for maintenance along

with additional optional treatments might be well appropriate.

This situation certainly poses opportunity for good word‐ofmouth

comments by the patient to family, friends, and potentially

coworkers. Alternatively, the patient might experience

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Scott Malingering HandoutDocument37 pagesScott Malingering HandoutFell SaenzNo ratings yet

- Protocols of The Illuminated Suns of The Golden Dawn - SteemitDocument1 pageProtocols of The Illuminated Suns of The Golden Dawn - SteemitZsi Ga100% (2)

- Mood Disorders Are The Most Common Psychological Diagnoses inDocument2 pagesMood Disorders Are The Most Common Psychological Diagnoses inLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Case Example: Obsessive-Compulsive DisorderDocument2 pagesCase Example: Obsessive-Compulsive DisorderLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Chu 11Document1 pageChu 11Lester MoeNo ratings yet

- Goldstein 29Document2 pagesGoldstein 29Lester MoeNo ratings yet

- Mood Disorders: DepressionDocument2 pagesMood Disorders: DepressionLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Of A Face. in Review of A Book Written by A Long Term Friend ThatDocument3 pagesOf A Face. in Review of A Book Written by A Long Term Friend ThatLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Treatment Planning: Predicting Patient ResponseDocument2 pagesPsychology and Treatment Planning: Predicting Patient ResponseLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Esthetics: A Health Science and ServiceDocument2 pagesEsthetics: A Health Science and ServiceLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Patient Response To AbnormalityDocument2 pagesPatient Response To AbnormalityLester MoeNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Facial Appearance: Dateline NBC, and Supermodel Turned Television Host TyraDocument2 pagesThe Importance of Facial Appearance: Dateline NBC, and Supermodel Turned Television Host TyraLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Functions of TeethDocument2 pagesFunctions of TeethLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Patient's Esthetic Needs: Physical Attractiveness PhenomenonDocument1 pageUnderstanding The Patient's Esthetic Needs: Physical Attractiveness PhenomenonLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Goldstein 9Document1 pageGoldstein 9Lester MoeNo ratings yet

- The Social Context of Dental EstheticsDocument2 pagesThe Social Context of Dental EstheticsLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Goldstein 2Document1 pageGoldstein 2Lester MoeNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspective of Dental Esthetics: OhaguroDocument2 pagesHistorical Perspective of Dental Esthetics: OhaguroLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Curbele Spee, Wilson Și Monson Nu Există La Arcadele Dentare NaturaleDocument1 pageCurbele Spee, Wilson Și Monson Nu Există La Arcadele Dentare NaturaleLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Bucuresti Cluj Napoca Craiova Iasi Oradea Sibiu Targu Mures TimisoaraDocument1 pageBucuresti Cluj Napoca Craiova Iasi Oradea Sibiu Targu Mures TimisoaraLester MoeNo ratings yet

- Psychosis in The Older PatientDocument25 pagesPsychosis in The Older PatientKreshnik IdrizajNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Mental Status ExamDocument14 pagesSchizophrenia and Mental Status ExamGeraldine TeneclanNo ratings yet

- 2016 What Is Psychosis Fact SheetDocument2 pages2016 What Is Psychosis Fact SheetGrace LNo ratings yet

- Nursing Management For Patients With DelusionsDocument13 pagesNursing Management For Patients With DelusionsAbeer salehNo ratings yet

- L 8 NewDocument13 pagesL 8 NewWeronika Tomaszczuk-KłakNo ratings yet

- Self and SchizophreniaDocument21 pagesSelf and SchizophreniaAriel PollakNo ratings yet

- PRELIMINARY Exam (CRIM SOC 3) HUMAN BEHAVIOR AND CRISIS MGMTDocument5 pagesPRELIMINARY Exam (CRIM SOC 3) HUMAN BEHAVIOR AND CRISIS MGMTDonnie Ray SolonNo ratings yet

- McCutcheon Et Al-2020-World PsychiatryDocument19 pagesMcCutcheon Et Al-2020-World PsychiatryRob McCutcheonNo ratings yet

- Delusion and Self-Deception - Affective and Motivational Influences On Belief Formation-Psychology Press (2008) (Macquarie Monographs in Cognitive Science) Tim Bayne, Jordi FernándezDocument312 pagesDelusion and Self-Deception - Affective and Motivational Influences On Belief Formation-Psychology Press (2008) (Macquarie Monographs in Cognitive Science) Tim Bayne, Jordi FernándezRey Jerly Duran BenitoNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgmentDocument44 pagesAcknowledgmentImtiaz HussainNo ratings yet

- ABPSYCH Practice ExamDocument16 pagesABPSYCH Practice ExamGlynis Marie AvanceñaNo ratings yet

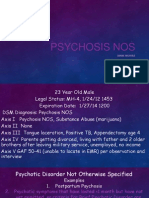

- Psychosis NosDocument8 pagesPsychosis Nosapi-253211220No ratings yet

- Case Study: 1. Bio Data of PatientDocument41 pagesCase Study: 1. Bio Data of Patientkiran mahalNo ratings yet

- NCMB317 Lec MidtermDocument55 pagesNCMB317 Lec Midterm2 - GUEVARRA, KYLE JOSHUA M.No ratings yet

- Human Behavior and VictimologyDocument25 pagesHuman Behavior and VictimologyAyessa Maycie Manuel OlgueraNo ratings yet

- SPMM Smart Revise Descriptive Psychopathology Paper A Syllabic Content 5.22 Mrcpsych NoteDocument43 pagesSPMM Smart Revise Descriptive Psychopathology Paper A Syllabic Content 5.22 Mrcpsych NoteBakir JaberNo ratings yet

- AbPsych Reviewer 5Document11 pagesAbPsych Reviewer 5Syndell PalleNo ratings yet

- Process RecordingDocument9 pagesProcess RecordingShiva CharakNo ratings yet

- AP Psych - Psychological DisordersDocument6 pagesAP Psych - Psychological DisordersKloie WalkerNo ratings yet

- Disturbed Thought Process NCP Gallano May 22 2018Document3 pagesDisturbed Thought Process NCP Gallano May 22 2018Charles Mallari ValdezNo ratings yet

- Mse - Mania, Depression, Paranoid SchizoDocument2 pagesMse - Mania, Depression, Paranoid SchizoBernice Joy Calacsan Daguna0% (1)

- CASC Summary Lawrence IsaacDocument126 pagesCASC Summary Lawrence IsaacTeslim RajiNo ratings yet

- Analisis Film Black Swan - Kel.3Document28 pagesAnalisis Film Black Swan - Kel.3Yuni WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For A Patient With SchizophreniaDocument14 pagesNursing Care Plan For A Patient With SchizophreniaMary Luz De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Assessment & Functional PatternsDocument30 pagesMental Status Assessment & Functional PatternsCharlz ZipaganNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument9 pagesMental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfGRUPO DE INTERES EN PSIQUIATRIANo ratings yet

- Love and Psychosis. Why Does Love Make Us Crazy?Document6 pagesLove and Psychosis. Why Does Love Make Us Crazy?LexDePraxisNo ratings yet

- Outline The Clinical Characteristics of SchizophreniaDocument1 pageOutline The Clinical Characteristics of Schizophreniadaljit-singhNo ratings yet