Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Work-Related Eye Injury: The Main Cause of Ocular Trauma in Iran

Uploaded by

fadil ahmadiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Work-Related Eye Injury: The Main Cause of Ocular Trauma in Iran

Uploaded by

fadil ahmadiCopyright:

Available Formats

Eur J Ophthalmol 2010 ; 20 ( 4 ): 770 - 775

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Work-related eye injury: the main cause of ocular

trauma in Iran

Mohammad Reza Mansouri1, Mona Hosseini2,3, Masoumeh Mohebi1, Fateme Alipour2,

Ramin Mehrdad4

1

Department of Ophthalmology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran

2

Eye Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran - Iran

3

Genomic Medicine and Statistics, University of Oxford, Oxford - UK

4

Department of Occupational Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran - Iran

Purpose. Occupational eye injuries are among the major causes of ocular trauma and can cause severe

visual impairment, with even minor injuries incurring considerable financial costs due to work absen-

teeism. This study was designed to evaluate the epidemiology of eye trauma and the role of occupa-

tional injuries at Farabi Eye Hospital, which is the largest eye hospital in Iran.

Methods. In this prospective, cross-sectional study, 822 eyes from 768 trauma patients presenting to

Farabi Eye Hospital were enrolled in the study. The Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology System and

the United States Eye Injury Registry model were adopted as the basis for the study questionnaire.

The questionnaires were completed through in-person interviews and comprehensive ocular exami-

nations.

Results. The mean age of ocular trauma patients was 31.11 years, and 685 (89.2%) patients were

male. Of all eye injuries, 73.7% were work-related. Only 2.2% of the patients were wearing safety

goggles at the time of injury. History of previous eye trauma was positive in 44.3% of cases. An Ocular

Trauma Score 3 or more was present in 4% of patients.

Conclusions. Work-related eye trauma is the major cause of eye injury in Iran and most often occurs

as a result of the lack of proper eye protection. Most work-related eye injury patients are young men.

(Eur J Ophthalmol 2010; 20: 770-5)

Key Words. Eye injury, Eye trauma, Iran, Occupational, Work-related

Accepted: August 13, 2009

INTRODUCTION

developing countries). Ocular trauma is more common in

young people (5), males, workers, and those who do not

Ocular trauma is a common cause of emergency ophthal- use safety goggles at work (6-11).

mologic visits. In the United States alone, it is estimated It has been suggested that about one quarter of all serious

that more than 2.4 million eye injuries occur annually (3). eye injuries are related to activities in the workplace (7).

The cumulative lifetime prevalence of eye injury in the Uni- Each year, more than 65,000 work-related eye injuries and

ted States is estimated to be over 1,400 per 100,000 popu- illnesses, with significant visual consequences, are repor-

lation (4). There are considerable discrepancies in inciden- ted in the United States (12). However, there is a substan-

ce by factors such as gender, age, occupation, and area tial lack of knowledge about the different aspects of eye in-

of residence (rural versus urban areas; developed versus juries in developing countries. Additionally, the proportion

770 © 2010 Wichtig Editore - 1120-6721

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 770 28-04-2010 17:20:11

Mansouri et al

of work-related eye injuries due to different causes varies the study questionnaire. In each case, the questionnaire

between countries (7), and findings from other developing was completed through an in-person interview and a com-

countries cannot be generalized to Iran. prehensive ocular examination. All interviews and exami-

Systematic collection of standardized data on the occur- nations were done by 3 ophthalmologists familiar with the

rence of eye injuries can lead to health system action plans study questionnaire.

to prevent serious visual impairment. Using the United Sta- Demographic data and data on the clinical presentation

tes Eye Injury Registry (USEIR) as our framework (1, 2), this such as cause and place of injury, use of protective eyewe-

study was designed to elucidate information regarding the ar, and nature of the injury as accidental or intentional were

causes, settings, possible prognosis, and role of work-re- collected via standardized questionnaires by the same

lated accidents in ocular trauma epidemiology in Iran. Our physician. The Ocular Trauma Score (OTS) (13) was calcu-

results provide useful information for ophthalmologists as lated for each injured eye.

well as the health system, and could be useful for preven- Data were analyzed by SPSS 16.0. We compared demo-

ting occupational eye injuries in the workplace. graphic data, clinical signs, and initial diagnosis between

occupational and nonoccupational subgroups using a t

test for continuous variables and the chi square test for

MATERIALS AND METHODS binary or categorical variables. p Values <0.05 were consi-

dered statistically significant.

In this prospective, cross-sectional study, 822 eyes from

768 ocular trauma patients presenting to the Farabi Eye

Hospital (Tehran, Iran) emergency clinic were enrolled. The RESULTS

study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of

Tehran University of Medical Sciences. All subjects signed A total of 822 eyes from 768 patients were evaluated in this

informed consent forms prior to participating in the study, prospective study. Age, gender, laterality of the injured eye

and patient care was independent of the patients’ deci- or eyes, and hospitalization are summarized in Table I.

sions regarding this issue. Approximately 73.7% of eye injuries were work-related.

One day in each week was randomly selected from Sep- Industrial environments were the most common site

tember 1, 2005, to February 28, 2006. During the selected for ocular trauma to take place (71.5%), with the home

days, all patients with complaints of trauma presenting to ranking second (13%), and streets or highways third

the Emergency Clinic at Farabi Eye Hospital were exami- (11%). The mean and mode time to presentation in the

ned. The Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology System (1) emergency room were 11 and 8 hours after the trauma,

and the USEIR model (2) were adopted as the basis for respectively, but the presenting time varied between im-

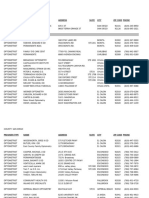

TABLE I - DEMOGRAPHIC DATA, LATERALITY, AND HOSPITALIZATION

Total, n=768 Work-related, n=566 Nonoccupational, n=202 p value

Age, y, mean (SD) 31.1 (12.7) 32.7 (11.00) 26.7 (15.8) 0.000*

Gender, n (%)

Male 685 (89.2) 545 (96.3) 140 (69.3) 0.000*

Female 83 (10.8) 21 (3.7) 62 (30.7)

Laterality, n (%)

Right 373 (48.6) 266 (47.0) 108 (53.5)

Left 336 (43.7) 252 (45.5) 83 (41.1) 0.198

Bilateral 59 (7.7) 48 (8.5) 11 (5.4) 0.164

Hospitalization, n (%)

No 730 (98.4) 544 (98.6) 186 (97.9) 0.54

Yes 12 (1.6) 8 (1.4) 4 (2.1)

*Statistically significant at <0.001.

771

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 771 28-04-2010 17:20:11

Work-related eye injury in Iran

mediately (less than 1 hour) to 240 hours. At the time of presentation, 3% of eyes had visual acuity

About 92% of eyes had no eye protection at the time of less than 20/200 and 1% of eyes had visual acuity betwe-

injury, and only 2.2% were protected by safety goggles. en 20/120 and 20/200. Fortunately, 88% had visual acuity

More than 95% of traumas were unintentional and 3.5% greater than 20/40.

of injuries were secondary to assault. Self-inflicted ocular The cornea was the most commonly involved tissue; distri-

traumas were reported in 0.7% of cases. bution of involved tissues is shown in Table II. Almost all

The 3 most common sources of trauma both for the group patients (97.7%) had more than one tissue involved.

as a whole and within the occupational group were scatte- Major diagnoses on presentation were open globe inju-

red particles of stone blade, blunt object, and arc welding, ry, intraocular foreign body, endophthalmitis, and corneal

with 40%, 16%, and 9%, respectively. In patients with no- burn. Table III shows the frequency and patterns of open

noccupational eye injuries, the 3 most common sources globe injuries.

were blunt objects (39.8%), sharp objects (14.8%), and Endophthalmitis was the initial diagnosis in 4 (0.5%) pa-

falls (6.5%). tients. All of the endophthalmitis cases had occupational

A history of previous eye trauma was positive in 44.3% of injuries. Intraocular foreign body (posterior or anterior) was

patients. Among those who had a positive history of trau- the initial diagnosis given to 2 (0.2%) patients; 1 had endo-

ma, 91.8% were work-related and the odds ratio for the phthalmitis at the time of initial presentation and both had

current injury being work-related was 7.72 (95% confiden- occupational injuries.

ce interval 4.93–12.09). Corneal burn was observed in 22 (2.7%) patients; 1.6%

TABLE II - COMPARISON OF INVOLVED TISSUES BETWEEN OCCUPATIONAL AND NONOCCUPATIONAL INJURED EYES

Involved tissue Total, Occupational, Nonoccupational, p value OR (95% CI)

n=822, n (%) n=606, n (%) n=216, n (%)

Lids 115 (14) 33 (5.4) 82 (38) 0.000* 0.09 (0.06–0.15)

Conjunctiva 153 (18.6) 80 (13.2) 73 (33.8) 0.000* 0.30 (0.20–0.43)

Lacrimal system 6 (0.7) 3 (0.5) 3 (1.4) 0.189 0.35 (0.07–1.76)

Cornea 648 (78.8) 538 (88.8) 110 (50.9) 0.000* 7.62 (5.28–11.00)

Sclera 9 (1.1) 7 (1.2) 2 (0.9) 1.000 1.25 (0.26–6.06)

Iris 21 (2.6) 14 (2.3) 7 (3.2) 0.457 0.70 (0.28–1.77)

Anterior chamber 46 (5.6) 20 (3.3) 26 (12) 0.000* 0.25 (0.14–0.46)

Lens 6 (0.7) 4 (0.7) 2 (0.9) 0.656 0.71 (0.13–3.90)

Vitreous 2 (0.2) 1 (0.2) 1 (0.5) 0.457 0.36 (0.2–5.70)

Retina 13 (1.6) 8 (1.3) 5 (1.3) 0.343 0.56 (0.18–1.74)

Macula 13 (1.6) 6 (1.0) 7 (3.2) 0.49 0.30 (0.10–0.90)

Choroid 3 (0.4) 3 (0.5) 0 (0.0) 0.571 1.00 (0.99–1.01)

Optic nerve 2 (0.2) 0 (0.0) 2 (0.9) 0.069 0.99 (0.98–1.00)

Extraocular muscles 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) NA NA

Orbit 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) NA NA

*Statistically significant at <0.001.

TABLE III - PATTERNS OF OPEN GLOBE INJURIES

Open globe injury Corneal, n (%) Scleral, n (%) Corneoscleral, n (%)

Full-thickness corneal laceration 13 (1.6) 4 (0.5) 0 (0.0)

Rupture 5 (0.6) 1 (0.1) 1 (0.1)

Penetrating Injury 11 (1.3) 1 (0.1) 2 (0.2)

Perforating Injury 3 (0.4) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.1)

772

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 772 28-04-2010 17:20:12

Mansouri et al

were chemical with 1.1% acidic and 0.5% alkali burns. cy of safety goggles in preventing eye injuries; however,

Corneal thermal and electrical burns were observed in because of our study design, we cannot know the ratio

0.9% and 0.2% of corneal burn patients, respectively. of their use in the general working population. More than

Among corneal burn cases, 59% (13 patients) were occu- 44% of cases had a history of previous eye trauma, but

pationally related. even in those with a positive history, only 1.9% wore safety

The OTS for injured eyes was calculated in 799 injured glasses at the time of injury. This is the same behavior as

eyes. In 23 patients, most of whom were children under 5 reported in Singapore (16). It clearly shows that awareness

years of age who could not cooperate for visual acuity te- of the possibility of trauma alone is not enough motivation

sting, the OTS could not be calculated. Results are shown to use safety goggles.

in Table IV. In one study in India, 97.8% of patients were not wearing

any eye protection at the time of trauma (10). This is similar

to our finding, and much lower than the reported use of

DISCUSSION safety goggles by 32% of US adults engaging in activities

that could cause an eye injury (17). It appears that the use

Our study population consisted mainly of patients who of preventive means is neglected in developing countries,

were male (more than 89%), workers (approximately 74%), and more attention should be paid to this issue.

and young people (mean age of 31 years). These findings Cornea was the only tissue which reached statistical signi-

are compatible with other published reports (6-11, 14, 15), ficance for more involvement among occupational injuries,

but the percentage of work-related ocular traumas is higher primarily because of the nature of work-related eye injuri-

in our study compared to rates of up to 25% in the litera- es, which usually result from foreign bodies. As the source

ture (7, 9). The reported ratio of occupational eye injuries in of trauma was scattered particles of stone blade in about

developing countries is higher. For example, work-related 40% of occupationally injured patients, most corneal injuri-

eye injuries are reported to be responsible for 20.5% to es were superficial corneal foreign bodies. Lid, conjunctiva,

56% of ocular traumas in Singapore (16) and 55.9% of eye and anterior chamber involvement were significantly more

injuries in a rural population in southern India (10). These prevalent among nonoccupational injuries. This differen-

differences can be attributed to differing study designs and ce is explained by blunt objects being the most common

variable definitions, cultural differences, different locations source of injury in this group.

(rural versus urban), and different patterns of ocular injuri- Although most of the injuries were minor and more than

es. Due to these factors, it is a widely held hypothesis that 86% of our patients had an OTS of 5, we did encounter 4

the incidence of ocular trauma varies by population, giving cases of endophthalmitis and 2 intraocular foreign bodies.

rise to the necessity of conducting epidemiologic studies All of these serious cases were occupationally related.

in each region. Also, from a preventive perspective, although most ocular

Only 3.6% of workers in our study were using safety gog- traumas are minor and do not require hospitalization (18),

gles at the time of injury. This finding may show the effica- each trauma indicates a lack of preventive measures and,

TABLE IV - OCULAR TRAUMA SCORE (OTS) AMONG INJURED, N (%)

OTS Total Occupational Nonoccupational p value

1 2 (0.3) 1 (0.2) 1 (0.5) 0.457*

2 6 (0.8) 2 (0.3) 4 (2.0) 0.044*†

3 23 (2.9) 14 (2.3) 9 (4.4) 0.155

4 77 (9.6) 50 (8.4) 27 (13.3) 0.066

5 691 (86.5) 529 (88.8) 162 (79.8) 0.001‡

Total 799 (100) 596 (100) 216 (100)

*p values by exact test.

†Statistically significant p<0.05.

‡Statistically significant p<0.01.

773

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 773 28-04-2010 17:20:12

Work-related eye injury in Iran

especially in work-related injuries, can be interpreted as a Several of this study’s strengths lie in its prospective nature,

shortage of laws, supervision, awareness, and accessibili- a relatively large sample size, and the use of a standardized

ty to proper safety equipment, leading to catastrophic se- questionnaire. Our study population may not be conside-

quela (18). Even minor traumas such as superficial corneal red to be a representative sample of all eye trauma patients

foreign bodies result in 1 to 2 days absence from work, throughout the country. Because Farabi Eye Hospital is the

and the accumulation of such absences results in signifi- largest eye hospital in Iran and additionally because of the

cant financial costs (7). Considering the workload in emer- services Farabi Eye Hospital offers, the hospital receives

gency ophthalmologic units and the expense of treatment, referrals from all over the country. Further research inve-

the economic consequences of eye injuries become even stigating the exact incidence of eye injuries throughout the

higher. country of Iran and its sequela are necessary.

In summary, occupational eye injuries are the most com-

mon cause of ocular trauma among Farabi Eye Hospital

emergency room patients. The high proportion of work- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

related eye trauma among our patients may be attributed

to several causes, the most important of which is the pro- The authors thank Drs. R. Ghafari and M. Malihi for their help in

bable low use of safety goggles among Iranian workers. visiting patients and Dr. Caroline Hedges for editing the manu-

Work-related ocular injuries have not received enough at- script.

tention in Iran. Many employers, especially those in small This study was supported by a grant from Tehran University of

businesses, do not provide appropriate safety goggles for Medical Sciences.

their employees, and even when the goggles are provided,

many workers do not use them at all because of inconve-

The authors report no proprietary interest.

nience or distortion of vision. Our data suggest that this

needs more attention.

Address for correspondence:

Eye injuries may be reduced substantially by educating Fateme Alipour, MD

workers about potentially risky behaviors and convincing Eye Research Center

Tehran University of Medical Sciences

them to use safety goggles, instituting laws requiring em-

Tehran

ployers to provide well-made, appropriate safety goggles 005 63110 Iran

for their employees, and close supervision. alipour@tums,.ac.ir

REFERENCES Sonographic evaluation of ocular trauma in Ilorin, Nige-

ria. Eur J Ophthalmol 2006; 16: 453-7.

1. Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD. Birmingham Eye 6. Mansouri MR, Mirshahi A, Hosseini M. Domestic ocular

Trauma Terminology (BETT): terminology and classifica- injuries: a case series. Eur J Ophthalmol 2007; 17: 654-

tion of mechanical eye injuries. Ophthalmol Clin North 9.

Am 2002; 15: 139-43. 7. Vasu U, Vasnaik A, Battu RR, Kurian M, George S. Occu-

2. Kuhn F, Pieramici DJ, eds. Ocular Trauma: Principles and pational open globe injuries. Indian J Ophthalmol 2001;

Practice. Italy: Thieme; 2002. 49: 43-7.

3. Salvin JH. Systematic approach to pediatric ocular trau- 8. Vats S, Murthy GV, Chandra M, Gupta SK, Vashist P, Go-

ma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2007; 18: 366-72. goi M. Epidemiological study of ocular trauma in an ur-

4. Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mann L. Epidemio- ban slum population in Delhi, India. Indian J Ophthalmol

logy of blinding trauma in the United States Eye Injury 2008; 56: 313-6.

Registry. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13: 209-16. 9. McCall BP, Horwitz IB. Assessment of occupational

5. Nzeh DA, Owoeye JF, Ademola-Popoola DS, Uyanne I. eye injury risk and severity: an analysis of Rhode Island

774

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 774 28-04-2010 17:20:12

Mansouri et al

workers’ compensation data 1998–2002. Am J Ind Med Clin North Am 2002; 15: 163-5, vi.

2006; 49: 45-53. 14. Ritenour AE, Baskin TW. Primary blast injury: update on

10. Krishnaiah S, Nirmalan PK, Shamanna BR, Srinivas M, diagnosis and treatment. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: S311-7.

Rao GN, Thomas R. Ocular trauma in a rural population 15. Gyasi M, Amoaku W, Adjuik M. Epidemiology of hospi-

of southern India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Stu- talized ocular injuries in the upper East region of Ghana.

dy. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 1159-64. Ghana Med J 2007; 41: 171-5.

11. Cillino S, Casuccio A, Di Pace F, Pillitteri F, Cillino G. A 16. Ngo C S LSW. Industrial accident-related ocular emer-

five-year retrospective study of the epidemiological cha- gencies in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Singapore

racteristics and visual outcomes of patients hospitalized Med J 2008; 49: 280-5.

for ocular trauma in a Mediterranean area. BMC Ophthal- 17. Forrest KY, Cali JM, Cavill WJ. Use of protective eyewear

mol 2008; 8: 6. in US adults: results from the 2002 national health inter-

12. Peate WF. Work-related eye injuries and illnesses. Am view survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2008; 15: 37-41.

Fam Physician 2007; 75: 1017-22. 18. Khatry SK, Lewis AE, Schein OD, Thapa MD, Pradhan

13. Kuhn F, Maisiak R, Mann L, Mester V, Morris R, Wither- EK, Katz J. The epidemiology of ocular trauma in rural

spoon CD. The Ocular Trauma Score (OTS). Ophthalmol Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 456-60.

775

EJO_09_84_ALIPOUR.indd 775 28-04-2010 17:20:12

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Spectacle Prescription by DR Harbansh LalDocument52 pagesSpectacle Prescription by DR Harbansh LalJatinderBaliNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Rumus Johnson Dan Rumus Risanto Dalam Menentukan Taksiran Berat Janin Pada Ibu Hamil Dengan Berat Badan BerlebihDocument4 pagesPerbandingan Rumus Johnson Dan Rumus Risanto Dalam Menentukan Taksiran Berat Janin Pada Ibu Hamil Dengan Berat Badan Berlebihfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Steroids and The Eye-Indications and Complications: W. J. DinningDocument5 pagesSteroids and The Eye-Indications and Complications: W. J. Dinningfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Right Lower Lid Entropion in A 79-Year-Old Female: A Case-ReportDocument4 pagesRight Lower Lid Entropion in A 79-Year-Old Female: A Case-Reportfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Asian Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty Sebagai Tatalaksana Dermatokalasis - Adessa RachmaDocument11 pagesAsian Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty Sebagai Tatalaksana Dermatokalasis - Adessa Rachmafadil ahmadi100% (1)

- Ocular Complications of Thermal Injury: A 3-Year RetrospectiveDocument4 pagesOcular Complications of Thermal Injury: A 3-Year Retrospectivefadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Visual Impairments in Young Children: Fundamentals of and Strategies For Enhancing DevelopmentDocument13 pagesVisual Impairments in Young Children: Fundamentals of and Strategies For Enhancing Developmentfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Amsler Grid PDFDocument1 pageAmsler Grid PDFfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric Assessment Triangle Webinar1Document25 pagesThe Pediatric Assessment Triangle Webinar1fadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Early Recovery Following New Onset Anosmia During The COVID-19 Pandemic - An Observational Cohort StudyDocument6 pagesEarly Recovery Following New Onset Anosmia During The COVID-19 Pandemic - An Observational Cohort Studyfadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- JMV 25815Document2 pagesJMV 25815fadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- 2277-Article Text-7155-4-10-20200122Document15 pages2277-Article Text-7155-4-10-20200122fadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Comprhensive Exam Queations PDFDocument27 pagesComprhensive Exam Queations PDFhenok birukNo ratings yet

- KERATOCONUSDocument22 pagesKERATOCONUSAarush DeoraNo ratings yet

- Mild or Pricking Pain: Trauma? Y NDocument4 pagesMild or Pricking Pain: Trauma? Y NHongMingNo ratings yet

- 3Rd Annual Transformational Ophthalmology Symposium: Saturday, OCTOBER 6, 2018 8:00 AM - 4:00 PMDocument5 pages3Rd Annual Transformational Ophthalmology Symposium: Saturday, OCTOBER 6, 2018 8:00 AM - 4:00 PMyos_peace86No ratings yet

- Journal Article 5 48Document3 pagesJournal Article 5 48LorenaNo ratings yet

- Optical Instrument: By: Sariyati, S.TDocument21 pagesOptical Instrument: By: Sariyati, S.TparamitaNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Adult Eye and Vision ExamDocument51 pagesComprehensive Adult Eye and Vision ExamAurel FeodoraNo ratings yet

- Comparing The Accommodation Facility Among The Emmetropes, Myopes and Hypropes and The Level of Recovery Among Them After Vision TherapyDocument26 pagesComparing The Accommodation Facility Among The Emmetropes, Myopes and Hypropes and The Level of Recovery Among Them After Vision TherapySHANKAR PRINTINGNo ratings yet

- Ospe Ophthalmology CorrectedDocument55 pagesOspe Ophthalmology CorrectedGgah Vgggagagsg100% (1)

- Management of Alkali Eye Injury: Abdulla A. Almoosa, MD Muhammad Atif Mian, FrcsedDocument3 pagesManagement of Alkali Eye Injury: Abdulla A. Almoosa, MD Muhammad Atif Mian, FrcsedChandra WulanNo ratings yet

- Practical Approach To Medical Management of Glaucoma: Dr. Ravi Thomas, Dr. Rajul Parikh, Dr. Shefali Parikh IJO MAY 2008Document25 pagesPractical Approach To Medical Management of Glaucoma: Dr. Ravi Thomas, Dr. Rajul Parikh, Dr. Shefali Parikh IJO MAY 2008Andi Ayu LestariNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Hyperopic SurpriseDocument4 pagesPrevention of Hyperopic SurpriseDavid MartínezNo ratings yet

- Exp 5..effect of Mydriatic and Miotic Drug On Rabbit Eye - LabmonkDocument6 pagesExp 5..effect of Mydriatic and Miotic Drug On Rabbit Eye - LabmonkSubodh ShahNo ratings yet

- BJSTR MS Id 004577Document8 pagesBJSTR MS Id 004577SartajHussainNo ratings yet

- Progressive LensesDocument4 pagesProgressive LensesrawanezahraNo ratings yet

- Scleral Lens GuideDocument8 pagesScleral Lens Guideadidao111No ratings yet

- MCQ in OphthalmologyDocument108 pagesMCQ in OphthalmologySushi HtetNo ratings yet

- Chotijah Auliana Gusti - Rhizopus Keratitis Associated With Poor Contact Lens HygieneDocument4 pagesChotijah Auliana Gusti - Rhizopus Keratitis Associated With Poor Contact Lens HygieneaulianaNo ratings yet

- Re TinosDocument31 pagesRe TinosAn Da100% (1)

- Glaucoma QuizDocument2 pagesGlaucoma QuizvoodooariaNo ratings yet

- Phacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery For Treatment ofDocument7 pagesPhacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery For Treatment ofRagni MishraNo ratings yet

- Write A Dialogue of at Least 150 Words Between A Nurse and A Patient Suffering of Earache/ An Eye ConditionDocument1 pageWrite A Dialogue of at Least 150 Words Between A Nurse and A Patient Suffering of Earache/ An Eye ConditionLaurusAdiaNo ratings yet

- AstigmatismDocument18 pagesAstigmatismAmie CuevasNo ratings yet

- Interpretasi Vision-Test JaegerDocument1 pageInterpretasi Vision-Test Jaegerbagol julegNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23 Indications and Contradictions For Contact Lens Wear PDFDocument16 pagesChapter 23 Indications and Contradictions For Contact Lens Wear PDFfakenameNo ratings yet

- Astigmatism Definition, Etiology, Classification, Diagnosis and Non-Surgical TreatmentDocument17 pagesAstigmatism Definition, Etiology, Classification, Diagnosis and Non-Surgical TreatmentRisky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Normal Postnatal Ocular DevelopmentDocument23 pagesNormal Postnatal Ocular DevelopmentSi PuputNo ratings yet

- Vision-SanDiego (1) - 231013 - 141100Document10 pagesVision-SanDiego (1) - 231013 - 141100fernyz2886No ratings yet

- Full Download Ati RN Proctored Leadership Form C 2016 PDF Full ChapterDocument35 pagesFull Download Ati RN Proctored Leadership Form C 2016 PDF Full Chapteroscines.filicide.qzie100% (12)