Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013

Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013

Uploaded by

ganvaqqqzz21Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013

Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013

Uploaded by

ganvaqqqzz21Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/281272724

Transcinema: The purpose, uniqueness, and future of cinema

Article · January 2013

CITATIONS READS

0 421

1 author:

Robert Beshara

Northern New Mexico College

50 PUBLICATIONS 26 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Lacanian Film Theory View project

Transpersonal studies View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Robert Beshara on 26 August 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

TRANSCINEMA:

THE PURPOSE, UNIQUENESS, AND FUTURE OF CINEMA

Robert Beshara, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, Georgia, USA

ABSTRACT

Trans- as a prefix means beyond but also through. Moreover, it means change and transcending.

Hence, transcinema is beyond conventional or mainstream notions of cinema and achieves its goals

through avant-garde and experimental styles, yet transcinema also resembles industrial cinema

functionally because similar tools are put to use (e.g., actors, cameras, a screenplay, locations, etc.) with

the main difference being in budget size, methodologies, aesthetics, and philosophy. The aim of

transcinema is to help us change through transcendence. Moreover, the prefix trans- serves as a

reference to transpersonal studies to allude to transcinema’s psychospiritual utility, that it can potentially

help us heal and grow as individuals and as a community. Three aspects of transcinema will be explored

in this paper: its transformative potential or purpose, its transdisciplinarity, and its future vis-à-vis

transhumanism.

Keywords: cinema, transformation, transdisciplinarity, transhumanism, transpersonal studies

1. INTRODUCTION

Etymologically, cinema—which was invented by the Lumière brothers in the 1890s—comes from the

French word cinématographe, which in turn comes from the Greek word kinēma or movement; motion

pictures imply a change across time and space—aka the magic of cinema. The cinematograph as a

word referred to several things: “a motion-picture camera, projector, theater, or show” (Merriam-

Webster’s online dictionary, n.d.); in other words, cinema from its inception was a social event made up

from a collection of things—a film, a projector, a screen, a dark room, an audience, etc.—that resulted in

a shared experience akin to a collective dream wherein one, among a group of strangers and/or

acquaintances, was transposed to another (perhaps, more subtle) dimension. Even though cinema is a

young art—a little more than a century old—no one can deny the powerful positive effects it has had on

individuals and communities around the world in its short span of existence as a source of entertainment

and enlightenment. However, it is not possible to talk about cinema without first talking a little bit about

its origins in theatre. One must go all the way back to Ancient Greece to understand the purpose of

cinema or at least some of its potentials. This may seem like a Eurocentric approach given that “[t]he

world’s earliest report of a dramatic production comes from the banks of the Nile […] somewhere around

the year 2000 B.C.” (Fort and Kates, 1935), but cinema happens to have been invented by the French

and even though it is a relatively new and still evolving technology/art form, its foundation in terms of

dramatic theory has been laid down by Aristotle in The Poetics, whether screenwriters and screenwriting

gurus know it or not. There is some universality to dramatic structure because when it works it is

effective regardless of nationality, so clearly cinema can transcend borders in terms of box office

success (e.g., Avatar) and perhaps it can transcend language, too (e.g., Koyaanisqatsi). We expect

transpersonal themes even from mainstream movies because we have a psyche, and we are curious as

meaning makers.

George Polti (1924) identified thirty-six dramatic situations by analyzing a number of Greek and French

dramatic works, this is reminiscent of the notion of Jungian archetypes or that there is a collective

unconscious that the entire humanity is tapping into, hence, explaining the universality of some recurrent

themes or plot ideas in plays and films from time immemorial (e.g., the father and son plot in Star Wars).

The question is not how many dramatic situations or archetypes there are exactly, but rather what is the

meaning of such a phenomenon? For after all, a human being is an animal symbolicum, to borrow Ernst

Cassirer’s term, trying to understand him/herself. Cinema, which can function as a cultural and/or

personal mirror, may help us in this process of self-reflection as is clear in this quote from Joseph

Campbell (1991) in The Power of Myth:

124 Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

Shakespeare said that art is a mirror held up to nature. And that’s what it is. The nature is your

nature, and all of these wonderful poetic images of mythology are referring to something in you.

When your mind is trapped by the image out there so that you never make the reference to

yourself, you have misread the image.

Cinema and transcinema are distinct for a variety of reasons; transcinema resembles conventional or

mainstream cinema functionally (i.e., in terms of the tools used, such as cameras, actors, locations,

etc.), but goes beyond the industrial/formulaic model epitomized by Hollywood into the more innovative

realms of the avant-garde and the experimental in terms of aesthetics, methodology, and philosophy.

Ideologically, transcinema embraces fringe people (e.g., minorities and the marginalized), fringe

theories, and fringe cinema (i.e., underground and independent filmmaking) for socioeconomic and

political reasons, and is critical of nationalism and globalization and their traps, such as the negative

stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in some American films.

After the advent of digital filmmaking—popularized by Lars von Trier, Mike Figgis, George Lucas, Robert

Rodriguez, and Michael Mann—gradually came the affordability of digital cameras and video editing

systems. These new technologies were empowering to many people in terms of creative expression be

they filmmakers or simply film lovers, and so the dominant monopoly of the studios was slightly

challenged and the fine line between expert and lay person was blurred. The DIY ethic became a

guiding principle, e.g., mumblecore (see Denby, 2009), and the Internet became a platform or a

playground for sharing video content or ideas with results ranging from the amateurish to the

professional. Internet film distribution is a viable alternative business model that is feared by the ‘Big Six’

because of how empowering it can be to independent filmmakers. Similarly, in the music world, David

Byrne (2007) who has been labeled “Rock’s Renaissance Man” by TIME magazine (1986) makes the

case that in the future less music will be purchased physically and more so digitally as downloads; is this

a metaphor for the mind-body problem? Journalist Ronald Bergan (2007) wrote an article for the

Guardian titled Is Cinema Dead? British filmmaker Peter Greenaway (2001) responded to Bergan’s

question in the affirmative six years before Bergan even asked that ominous question:

I think that the cinema died on the 31st of September 1983. There is a reason for that, because

on 31st of September 1983 the remote control, the zapper was introduced into the living rooms

of the world. Cinema is a passive medium. I never quite understood really how it works. […] So,

you are sitting in the dark, man is not a nocturnal animal […] looking in one direction, sitting still?

And you commit yourself to the flat screen on which there are colored shadows. What an

extraordinary description of an obsession. Unfortunately, I think, if the cinema died in 31st of

September 1983 I think it was a still birth, because I don't think any of you in this room have

seen any cinema yet. All you have seen is 105 years of illustrated text and that is not the same

thing.

One of Greenaway’s recent projects is called LUPERPEDIA and it is described as “the Live Cinema

Event of the Tulse Luper Suitcases Project, an encyclopedic multi-media show deliberately made for the

Information Age” (European Graduate School, 2011). It can perhaps be experienced as merely a

sophisticated avant-garde VJ show with which Greenaway has successfully toured the world, or we can

think of it as stretching the limits of cinema. The project is described as deliberately made for the

“Information Age” because of its interactive nature akin to Web 2.0. If cinema is indeed dead, one is left

with the spiritual question: is there an afterlife? And if so, what is it like? Perhaps, the death of cinema is

the rebirth of cinema as transcinema: resuscitating its therapeutic/healing purpose in terms of dramatic

structure through a revival of the Aristotelian notion of catharsis. Wassily Kandinsky (1977), the

transpersonal Russian painter and art theorist who happened to be a synesthete, wrote: “That is

beautiful which is produced by the inner need, which springs from the soul.” He was critical of art for art’s

sake and as is clear from his quote, he saw tremendous value in an aesthetic informed by spirituality.

The main arguments of this paper is that transcinema can be transformative psychospiritually, that

transcinema is unique due to its transdisciplinarity, and that there may be no difference between cinema

and cinephiles in the future as more advanced machines and more evolved humans interconnect at a

level of unprecedented complexity, a position commonly known as transhumanism.

Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology 125

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

Before going any further, it is important to sift through the terms film, cinema, and movies since they are

different and, hence, are not interchangeable. LeCambrolieur (2012) situates cinema at the high-art end

of the spectrum, while positioning film as the middle ground, and movies as the most casual of the three.

Video would refer to electronic moving pictures, whether analog or digital. Movies is the most popular

term in North America as used by Hollywood to denote the economics of the medium, while film and

cinema are more popular outside of the US as they tend to be regarded as referring to more challenging

or highbrow motion pictures. However, there is a subtle but significant distinction between cinema and

film: “The filmic is the idea of an aspect of art and its relationship with the entire world around it. The

cinematic attempts to define the aesthetic and deal with the internal structure of the art” (LeCambrolieur,

2012). In this paper, the focus is primarily on the latter, but reference to the former is made when

appropriate, and the colloquial term movies is sometimes used, too, depending on the context. It is also

important to point out that the scope of this paper revolves mostly around feature films, whether fiction or

nonfiction.

2. TRANSFORMATION

Peter Greenaway (2001), in a lecture given at the European Graduate School in Switzerland, said:

I think that art is the most powerful educational tool that any of us have ever had, because it

communicates obviously not only in terms of intellect and rationality, but spiritually [emphasis

added] and for all the other reasons for which we exist here in a civilized state.

The purpose of this section is to highlight the therapeutic and/or healing potential of cinema vis-à-vis its

common function as a source of entertainment. The term ‘movie industry’ can seem like an oxymoron to

some, especially if one sees cinema as an art form and not merely a commodity. Undoubtedly, it takes a

sizeable amount of resources and hard work to make a film, so it is reasonable to expect revenue back.

However, we live in a time when making a huge profit may be the main incentive behind jumpstarting a

feature film project. This capitalist approach to filmmaking is epitomized by the Hollywood system and it

can sometimes bear good results, but in most cases there is a heavy reliance on formulas based on

what films have succeeded in the past particularly when it comes to writing a screenplay, which is

perhaps one of the most challenging parts of the filmmaking process since it is the barebones structure

or foundation of a film. The core ethic of mainstream cinema today seems to be inspired by the pleasure

principle of profit, which is a deviation from the true purpose of cinema.

Certainly, many people go to the movies to get distracted from their daily worries and that may be a

legitimate form of escapism, but going to the cinema because it is pleasurable should be half of the

story. The other half is that cinema can help us transform suffering, whether as audience members or as

filmmakers. The metaphor of the cinema screen as a mirror is fitting here because cinema at its worst

can be an exercise in narcissism wherein what is reflected can make us delusional. At its best, cinema

can reflect truths, whether beautiful or ugly, to help us manage and change some of our parts or

subpersonalities as we identify with the protagonist in his or her struggle. In The Matrix (1999), which

explores many philosophical and spiritual themes, before Neo wakes up from the matrix he looks at a

mirror and touches it to realize that it has a fluid structure, this series of surreal shots, one can argue,

marks a major plot point or transition in the film that compellingly seems symbolic of the difference

between maya (Sanskrit for illusion) and brahma (Sanskrit for the ultimate ground of all being) to use

Hindu terminology. Neo experiences an awakening both literally and symbolically (or spiritually) as he

shifts from the matrix to the real world. Enlightenment is often conceptualized as a positive experience,

but it is neither positive nor negative. In other words, it is beyond positive and negative. Neo wakes up to

the painful truth of reality—the red pill—that looks worse than the illusory world of the matrix—the blue

pill; that is his experience of awakening. Transcinema is like the red pill, but ultimately the choice is ours.

Rob Ager (2008) writes about the mysterious monolith from Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A

Space Odyssey, which was hailed as “the greatest sci-fi film of all time” by the Online Film Critics

Society (2002), as a metaphor: “For Bowman, the realization of the cinema screen paradigm creates a

doorway through which he can symbolically leave his own universe. Reborn in the enclosed renaissance

126 Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

room, which has no doorway, the camera assumes his point of view and moves directly into the upright

monolith. In this shot the monolith acts as a doorway straight back to Bowman’s own cinematic

universe”. To take this further, we can think of the cinema screen as a portal, which can transpose us as

viewers to different worlds, wherein we can experience all sorts of emotions and learn all kinds of things

that would normally take us lifetimes to experience or learn.

Kaplan (2005) does an excellent job naming some of the transpersonal dimensions of cinema, such as:

“transpersonal elements inherent in the nature of the cinematic medium; transpersonal influences on the

cinematic content, structure, and style; and potential transpersonal effects of the cinematic experience.”

In the beginning of his paper, he highlights the transpersonal nature of any creative medium, but

particularly in the cinematic medium, the interconnectedness between the minds of the filmmakers and

the film viewers through the film experience. This intersubjective outlook on cinema brings to light the

potential of the cinematic medium as a cultural therapeutic to use Robert D. Romanyshyn’s term.

Romanyshyn (2008), building on Van den Berg’s work, writes: “we are not surprised that Van den Berg

even coins a new word for neuroses, calling them ‘socioses’ (1971, p. 341). […] It acknowledges that the

social-cultural world is the field of human psychological life. There is a not a social world apart from the

psychological world, acting upon it from the outside. Rather the psychological world is the social world,

and the social world is the visible expression of the psychological world, the place where psychological

life is made concrete and incarnate. It follows, then, that any psychotherapy of neuroses will be a

therapy of the social world, or as we have said a cultural therapeutics.”

Cinema can be therapeutic and/or healing; the difference being that therapy involves psychological or

personal work while healing involves spiritual or transpersonal work. The difference may be subtle;

hence, a hybrid term such as ‘psychospiritual’ may conveniently be a better alternative in some cases to

bridge both words. Humphry House (1966) in writing about Aristotle’s Poetics explains that it is not

important whether catharsis is a metaphor from religion or medicine, in either case it is a technical term

which results in “an emotional balance and equilibrium: and it may well be called a state of emotional

th

health.” The therapeutic purpose of tragedy, hence, was explored since the 18 Century B.C. if not

before. House adds that “Aristotle’s educative and ‘curative’ theory [i.e., the purging of emotions through

pity and fear] has a very important element of permanent truth in it” and this is contrasted by the effect of

“inferior art,” namely “sentimentality,” which is prominent in many Hollywood movies. Andrzej Szczeklik

(2005) may have an answer as to why we talk about the magic of cinema: “Medicine and art are

descended from the same roots. They both originated in magic—a practice based on the omnipotence of

the word.” Chilean filmmaker and “father of the midnight movie,” Alejandro Jodorowsky, who came up

with his own psychospiritual system known as Psychomagic takes the notion of catharsis further by

saying: “The world is ill. We need to make therapy pictures. If art is not a medicine for the society, it is a

poison” (ABKCO Films, 2007). Jodorowsky is an excellent example of a transcineast because he is a

transdisciplinary artist who explores transpersonal themes under the stylistic umbrella of surrealism, and

he makes films with the intention that they may be therapeutic/healing. For example, El Topo (1970) is

an Eastern—exploring the Western genre through East Asian spiritual themes—, The Holy Mountain

(1973), which was produced by John Lennon, was made to simulate some of the subjective effects of an

LSD trip by delving into all sorts of esoteric symbolism ranging from Zen Buddhism to alchemy, and

Santa Sangre (1989), which was inspired by a real story, shows us the making and unmaking of a serial

killer. But what does catharsis exactly mean? According to Joe Sachs (2005): “Catharsis in Greek can

mean purification. While purging something means getting rid of it, purifying something means getting rid

of the worse or baser parts of it.” This means that pity and fear, or suffering in general, may be useful to

us because as symptoms they are there for a reason but the key thing is to be mindful of our suffering

and not to identify with it to be able to transform it, or to put a positive spin on the previous analysis, “for

many alchemists the purification of metals in alchemical transmutation was matched by a purification of

the soul [or mind], a kind of self-transmutation in the Hermetic Great Work” (Morrisson, 2007). Therefore,

watching or making transcinema should feel like an alchemical process.

American poetic filmmaker, James Broughton, wrote a short hymn in his book Seeing The Light (1978)

titled “The Secret Name of Cinema is Transformation”. Even though most (if not all) films may be argued

to be transpersonal in one way or another, some film styles are more synergistic than others with

regards to transpersonal content and structure. Kaplan (2005) thinks that “the surrealistic and

expressionistic styles appear to have a greater capacity for the expression of transpersonal concepts

Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology 127

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

and experiences because of the symbolic, intuitive, visceral, and arational nature of these styles.” What

may be added to that statement is that surreal films have had an affinity with psychoanalysis historically

for surrealism’s goal is “to develop the human personality by bringing repressed desires into

consciousness” by integrating “the irrational with the rational” through translating unconscious content

(e.g., dreams, memories, visions) to conscious cinematic images (Duplessis, 1962); however,

transcinema is not just surreal, it more broadly tends to be avant-garde or experimental. Transcineasts

are auteurs who explore transpersonal themes in their films; the alchemical process of the film may have

been healing/therapeutic to the filmmaker(s) and/or the film director may have had the intention that the

end product lends itself to be psychospiritually transformative to audience members. Examples of

transcinema include some of the works of the following transcineasts: Maya Deren (e.g., Meshes of the

½

Afternoon), Federico Fellini (e.g., 8 ), Andrei Tarkovsky (e.g., Stalker), Stanley Kunbrick (e.g., 2001: A

Space Odyssey), Alejandro Jodorowsky (e.g., The Holy Mountain), and David Lynch (e.g., Eraserhead).

It may be surprising to some of the readers to include a dark film that impeccably captures depression as

transcinematic, but Lynch himself wrote: “Eraserhead is my most spiritual movie. No one understands

when I say that, but it is” (2006). A spirituality that only focuses on the bright side of things is a superficial

one; a more holistic approach to spirituality is one that acknowledges both the darkness and the

lightness of the human condition a la the yin-yang. It is not within the scope of this paper to explore this

issue at length, but suffice it to say that there is value in the experience of ‘the dark night of the soul’

because it is through contrast that we can come to understand and maybe appreciate what is present

and what is lacking.

Perhaps to conclude this section, the personal dimension of transcinema can be highlighted. For one

reason or another, some expressive therapies are more popular than others; the most prominent ones

include art therapy, drama therapy, and music therapy. But what about cinema therapy? Why is that field

virtually unknown or not widely researched even though cinema plays an increasingly central role in a lot

of cultures worldwide? Cinema therapists (see Solomon, 2001; Wolz, 2005; Niemiec and Wedding,

2008) use films as a psychospiritual tool in their practice. These psychologists tend to prescribe the

appropriate films (i.e., films exploring concerns—usually experienced by the protagonist—that resonate

with the client’s concerns) to their clients. As the client identifies with the film’s protagonist, s/he may be

able to work through some of their issues slowly but surely.

In addition to the previous formal psychotherapeutic model, there is also value in healing through the

filmmaking process, whether one is a novice or an expert. Jodorowsky (2010) argues against the

limitations of talk therapy and for the possibilities of Psychomagic: “ I realized immediately that no true

healing could take place if one did not take some concrete action […] a creative action accomplished in

reality.” Confessional cinema, which is explored at length by filmmaker/film professor Caveh Zahedi,

could be regarded as a Psychomagical film genre because it tends to rely on the filmmaker sharing

his/her vulnerabilities during the process as they are trying to change a negative aspect about

themselves—see I Am A Sex Addict (Zahedi, 2005). To reiterate some of what was said in the

introduction, we live in revolutionary times because the technologies of the day have the potential to

bring all of us Internet users together. Today, we feel virtually more interconnected yet more

disconnected socially. Cinema can change that because it is a sacred space, where strangers gather

together in darkness. Certainly, filmmaking may be technically and/or aesthetically challenging, but with

minimal costs, some reading, and trial and error anyone can become an amateur filmmaker. We can use

all of these technologies that we have available to us at the present moment to help us heal and grow as

individuals and as communities, as we express ourselves creatively and communicate our uniqueness

artistically. Our video diaries or essay films can be regarded as an attempt to understand the human

condition a little bit better, or as a psychospiritual experience, wherein there was an attempt to spread

awareness and educate others and ourselves in a transcinematic process.

3. TRANSDISCIPLINARITY

To address what makes cinema unique, reference will be made to Ricciotto Canudo’s reflections on

cinema, which he regarded as ‘the seventh art.’ Canudo extends G.W.F. Hegel’s aesthetics, wherein the

latter conceptualized “the five arts [architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and poetry] that he thinks are

made necessary by the very concept of art itself” (Houlgate, 2010), the former added dance as the sixth

128 Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

art—initially it was cinema—and cinema as the seventh art, which according to Canudo synthesized yet

went beyond all of the Rhythmic arts of Space (aka the Plastic Arts) and Time—i.e., music, poetry, and

dance—combined (Abel, 1993). Perhaps transcinema sculpts in spacetime, to riff off Andrei Tarkovsky,

and interdimensionally transposes us viewers from the second dimension (i.e., a flat screen) to the third

dimension (i.e., a transcinematic experience). Canudo implicitly hints to the transpersonal nature of

cinema in 1923 when he writes:

Action in—only in—the cinema should be nothing more than a corporeal detail, a material

consequence, a visual expression of a collective psychology. The theatre, on the other hand,

can only focus on the individual and will always remain more oriented toward the specifically

psychological. Cinema will thereby prove to be the supreme artistic means of representation and

expression of milieus and people. It will cease being ‘individual,’ copying the theatre, which in

turn copies life (Abel, 1993).

Cinema would not have existed if it were not for theatre, so no need to be ungrateful about cinema’s

roots; however, the variables of location, camera angles, shot sizes, and post-production technologies

(e.g., CGI and color grading) among others make cinema stand apart. Perhaps, to highlight one aspect

of transcinema’s transdisciplinarity one could refer to Sergei Eisentein’s transcendent notion of the

‘synchronization of the senses’ or “the integration of word, image and sound, and the accumulation of

successive images and sounds [that serve] to construct perception, meaning, and emotion (p. 69)”

(quoted in Kaplan, 2005). A fine example of that to mention but one would be ‘The Blue Danube’

sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey, which “[a]t first glance […] may seem long and unnecessary but it

is a crucial scene to understanding Kubrick’s vision of the future. The use of music and movement is

designed to give the impression of the machines waltzing, which is the ultimate expression of the state of

grace that humanity-built technology has now achieves” (Caldwell, 2011). That sequence conveys a lot

of visual information that forces us to react emotionally and to construct meaning as we are interpreting

the images and the sounds being juxtaposed, and all of that happens without the use of any dialogue

and it is this translinguistic potential of transcinema that can render it indeed a universal language.

Another excellent example of a translinguistic film would be the prototypical experimental documentary

film Koyaanisqatsi (1982) which showcases some of the effects that human beings have had on nature

over time and some of the effects of technology on us, and this is shown to us by resorting only to edited

moving images and a minimalist soundtrack. Of course, some techniques (e.g., slow motion and time-

lapse cinematography) were used as part of the film’s vocabulary but there was no use of dialogue

proper.

Kaplan (2005) names the emergence of trans-genre (e.g., Star Wars and The Matrix) and trans-media

(e.g., !Women Art Revolution) as cinematic structures that “seek to transcend the boundaries of some

aspect of the Cartesian-Newtonian constructs of time and space.” These are useful terms to know

especially in the age of New Media and globalization because they point to the multi-layered

hybridization that has been taking place worldwide, but most specifically in the developed world.

4. TRANSHUMANISM

In a very inspiring article titled The Future of Science…Is Art?, Jonah Lehrer (2008) writes:

If we are serious about unifying human knowledge, then we’ll need to create a new movement

that coexists with the third culture [which consists of scientists talking directly to the general

public] but that deliberately trespasses on our cultural boundaries and seeks to create

relationships between the arts and the sciences. The premise of this movement—perhaps a

fourth culture—is that neither culture can exist by itself. Its goal will be to cultivate a positive

feedback loop, in which works of art lead to new scientific experiments, which lead to new

works of art and so on.

Perhaps, not only are we in need for a ‘fourth culture,’ maybe we need to reflect on ourselves as mutants

that are developing and evolving into a fourth brain because according to Jodorowsky (2010):

“Entertainment that sedates serves nothing; well, maybe to be able to bear life, right? I amuse myself.

Like a little dwarf, I entertain myself with American movies, which serve to dull the brain. But all of this

Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology 129

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

pseudo-art does not change society. Although really society should not change, it should mutate. And

little by little, it is mutating.” This may seem like a creative spree, but it echoes Ray Kurzweil’s (2005,

p.9) words: “The Singularity will represent the culmination of the merger of our biological thinking and

existence with our technology, resulting in a world that is still human but that transcends our biological

roots. There will be no distinction, post-Singularity, between human and machine or between physical

and virtual reality.” Even though Kurzweil (p. 145) thinks, “nonbiological mediums will be able to emulate

the richness, subtlety, and depth of human thinking,” they, according to him, “will not automatically

produce human levels of capability (e.g., musical and artistic aptitude, creativity, etc.). In other words, in

the future envisioned by Kurzweil, transcineasts will still have a role to play as “patternists” who arrange

let’s say shots in just the right way that they transcend their materiality and randomness to become art in

a more holistic fashion, this is the “magic” of cinema or the transcendence of all levels of reality—natural

and man-made. This spiritual aspect of the Singularity does not make it antithetical to evolution because

“[a]s a consummation of the evolution in our midst, the Singularity will deepen all of these manifestations

of transcendence” (p. 388). To the Sinularitarian, transcinema would be regarded as a useful form of

knowledge (p. 372). An exemplar of a Singularitarian transcineast would be Greenaway especially with

his project LUPERPEDIA, which claims to be “a highly innovative audio-visual experiment intended to

challenge the borders of film language [i.e., boundary-transcending] and offer the audience a totally new

[trans]cinematic experience” (European Graduate School, 2011). Will we as film viewers interact with the

films we are watching a la Web 2.0 so as to change the course of the plot? Will we download digital films

in the future directly to our brains? These provocative questions are open for scholars to think about as

they imagine the future of cinema in regards to content, form, structure, and purpose particularly in the

context of emerging new media technologies and the overall fast rate of technological acceleration.

5. CONCLUSION

Robert Wise has observed perhaps the most powerful effect that transcinema can have on us at the

level of the collective consciousness when he “noted the possible connection between the evolution of

consciousness and the evolution of the cinema [thanks to neuroplasticity]. […] Wise explained that when

he first started in the film industry the motion picture audiences required very clear linear story

structures, and that gradually through his career the audiences seemed to develop the ability to more

readily and quickly project meaning across discontinuous and non-linear cinema structure” (quoted in

Kaplan, 2005). Examples of nonlinear films include: The Killing (1956), Pulp Fiction (1994), The Thin

Red Line (1998), Magnolia (1999), Mulholland Dr. (2001), Memento (2000), Eternal Sunshine of the

Spotless Mind (2004), and Babel (2006). This shows that films are getting more and more complex—

structurally at least—, and so filmmakers’ techniques and artistic sensibilities are getting more

sophisticated (especially with the evolution of film technologies) and film viewers’ appreciation for

complexity is growing.

To conclude, it is worth pointing out some trends about the tastes of mainstream cinema fans and critics

nowadays because they hint that there is an implicit longing for transpersonal themes even from

Hollywood movies. As of 06 April 2013, The Shawshank Redemption (1994) tops the list of top 250

movies based on 946,828 votes as voted by IMDB users who gave the film the highest rating: 9.2/10

(“Top 250 movies as voted by our users”). The film’s central theme is hope—one of two words used by

the Barack Obama presidential campaign in 2009 that seems to have resonated with many people back

then. The Internet Movie Database is a popular website and it can be regarded as an online democratic

platform wherein Internet users who are film lovers can vote for their favorite films. The spectrum of

voters includes lay people, experts, and everyone in between, whether male or female, old or young, or

American and non-American. On Box Office Mojo, Avatar (2009) tops the list of all-time worldwide

grosses making more than two billion dollars (“All Time Box Office”). The central visual motif in that film

is the Kabalistic tree of life, which is a symbol for interconnectedness. Is it a coincidence that the

highest-grossing film of all-time across the world is a spiritual sci-fi film that sort of preaches peace?

Brussat and Brussat (2012) in their analysis of the film write: “Cameron gives the People an Earth-based

cosmology that is totally in sync with contemporary spirituality movements: reverence for Gaia (earth) as

a living being and the Oneness movement that celebrating the interconnection of all being.” The purpose

of cinema cannot simply be mere entertainment; otherwise, “the most selected ‘alternative’ faith on the

Census […] in England and Wales” wouldn’t be Jediism, which is a result of the influence of Star Wars

130 Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

on the collective consciousness (Taylor, 2012). Why would The Wizard of Oz, a film made in 1939, get a

100/100 rating by critics on Metacritic (“Movie Releases by Score”) and still be considered relevant by

critics and relatable by viewers today? Perhaps because there are spiritual lessons we can still learn

from it seventy-four years later? Such as: “There’s no place like home. The kingdom of heaven is not a

place; but a condition” or that “Truth is found in your own back yard,” and others (Johnson, n.d.).

Ultimately, “any film can become transpersonal” as, stated by Kaplan (2005), and the key thing is to be

mindful of the process of making films or watching them so as to be able to use the experience as an

educational and transformative tool for personal and transpersonal (or collective) growth and

development. Cinema is unique, and its future may lie in transcinema, but at the moment we must focus

on its transformative purpose particularly after realizing that there is a clear longing for spiritual themes

by a large number of people. This does not come as a surprise and Aristotle was right about the

cathartic purpose of tragedy or drama more than two millennia ago!

REFERENCE

Abel, R. 1993. French Film Theory and Criticism: A History/Anthology, 1907-1939. Volume 1: 1907-

1929, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

ABKCO Films. 2007. The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky Box Set. [Online Video]. Available at:

http://www.abkco.com/index.php/films/film/11. [Accessed: 07 April 2013].

Ager, R. 2008. Kubrick: and beyond the cinema frame. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.collativelearning.com/2001%20chapter%202.html. [Accessed 07 April 13].

“All Time Box Office”, Box Office Mojo. Available at: http://www.boxofficemojo.com/alltime/ [Accessed 07

April 2013].

Bergan, R. 2007. Is cinema dead?. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/filmblog/2007/aug/20/comparedtothefirsthalf. [Accessed 07 April 13].

Broughton, J. 1978. Seeing The Light, City Lights Books, San Francisco, CA.

Brussat, F. and Brussat, M.A. 2012. “Avatar”, Spirituality & Practice. Available at:

http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/films/films.php?id=19534 [Accessed 07 April 2013].

Byrne, D. 2013. David Byrne's Survival Strategies for Emerging Artists. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.wired.com/entertainment/music/magazine/16-01/ff_byrne?currentPage=all. [Accessed 07

April 2013].

Campbell, J. 1991. The Power of Myth, Anchor Books, New York, NY.

Caldwell, T. 2011. “Free Will, Technology and Violence in a Futuristic Vision of Humanity – 2001: A

Space Odyssey”, Screen. Available at: http://blog.cinemaautopsy.com/2011/06/03/free-will-

technology-and-violence-in-a-futuristic-vision-of-humanity-2001-a-space-odyssey/ [Accessed 07 April

2013].

cinematograph. 2013. In Merriam-Webster.com.

Available at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cinematograph [Accessed 07 April 2013].

Denby, D. 2009. Youthquake : The New Yorker. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/cinema/2009/03/16/090316crci_cinema_denby. [Accessed 08

April 2013].

Duplessis, Y. 1962. Surrealism, Walker and Company, New York, NY.

European Graduate School. 2011. “LUPERPEDIA Peter Greenaway BIEFF 2011 Opening Gala”,

Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/events/190450071037711/ [Accessed 07 April

2013]

Fort, A.B. and Kates, H.S. 1935. Minute History of the Drama, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY.

Greenaway, P. 2001. The Tulse Luper Suitcase. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.egs.edu/faculty/peter-greenaway/articles/the-tulse-luper-suitcase/. [Accessed 07 April 13].

Houlgate, S. 2010. "Hegel's Aesthetics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N.

Zalta (ed.), Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2010/entries/hegel-aesthetics/

[Accessed 07 April 2013].

House, H. 1966. Aristotle’s Poetics: A Course of Eight Lectures, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, UK.

Jodorowsky, A. 2010. Psychomagic:The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy, Inner

Traditions, Rochester, VT.

Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology 131

Volume VII Number I ISSN 2327-7017

Johnson, A. n.d. “The Spirituality of Oz: The Meaning of the Movie”, The Theosophical Society of

America. Available at: http://www.theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/1555 [Accessed 07

April 2013].

Kandinsky, W. 1977. Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, NY.

Kaplan, M.A. 2005. “Transpersonal Dimensions of the Cinema”, The Journal of Transpersonal

Psychology, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 9-22

Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Penguin Group, New

York, NY.

Lynch, D. 2006. Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity, Penguin Books,

London, UK.

LeCambrioleur. 2012. Film, Cinema, Movies and the difference between the three. [ONLINE] Available

at: http://www.ign.com/blogs/lecambrioleur/2012/07/17/film-cinema-movies-and-the-difference-

between-the-three. [Accessed 07 April 13].

Lehrer, J. 2008. “The Future of Science…Is Art? FOURTH CULTURE”, SEED. Available at:

http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/the_future_of_science_is_art/ [Accessed 07 April 2013].

Morrisson, M.S. 2007. Modern Alchemy: Occultism and the Emergence of Atomic Theory, Oxford

University Press, Inc., New York, NY.

“Movie Releases by Score”, Metacritic. Available at:

http://www.metacritic.com/browse/movies/score/metascore/all?sort=desc&view=condensed

[Accessed 07 April 2013].

Niemiec, R.M. and Wedding, D. 2008. Positive Psychology at the Movies: Using Films to Build Virtues

and Character Strengths, Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Cambridge, MA.

Polti, G. 1924. The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations, James Knapp Reeve, Franklin, OH.

Romanyshyn, R.D. “The Despotic Eye: An Illustration of Metabletic Phenomenology and Its

Implications”, Janus Head, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 505-527.

Taylor, H. 2012. “'Jedi' religion most popular alternative faith”, The Telegraph. Available at:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/religion/9737886/Jedi-religion-most-popular-alternative-faith.html

[Accessed 07 April 2013].

The Online Film Critics Society. 2002. 2001: A Space Odyssey Named the Greatest Sci-Fi Film of All

Time. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://web.archive.org/web/20061126071451/http://ofcs.rottentomatoes.com/pages/pr/top100scifi.

[Accessed 07 April 13].

TIME Magazine Cover: David Byrne - Oct. 27, 1986 - Rock - Music. [ONLINE] Available at:

http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19861027,00.html. [Accessed 08 April 2013].

Top 250 movies as voted by our users, IMDB. Available at:

http://www.imdb.com/chart/top?ref_=nb_mv_3_chttp [Accessed 07 April 2013].

Sachs, J. 2005. Aristotle: Poetics. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.iep.utm.edu/aris-poe/. [Accessed

07 April 13].

Solomon, G. 2001. Reel Therapy: How Movies Inspire You to Overcome Life's Problems, Lebhar-

Friedman Books, New York, NY.

Szczeklik, A. 2005. Catharsis: on the art of medicine, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Wolz, B. 2005. E-Motion Picture Magic: A Movie Lover’s Guide to Healing and Transformation,

Glenbridge Publishing Ltd., Centennial, CO.

Zahedi, C. 2005. I Am a Sex Addict. [DVD] United States.

AURHOR PROFILE

Robert Beshara (M.F.A., Governors State University) is a doctoral student in Psychology

(Consciousness and Society) at the University of West Georgia. His areas of research include film

studies and transpersonal psychology. He is also a filmmaker whose work has been shown at the New

York International Film & Video Festival, El Sawy International Film Festival, the International ArtExpo,

the One-Minute Film Festival, the Chicago International Movies and Music Festival, and the Dubai

International Film Festival.

132 Review of Social Studies, Law and Psychology

View publication stats

You might also like

- Agnes Pethő - Cinema and IntermedialityDocument441 pagesAgnes Pethő - Cinema and Intermedialityramayana.lira2398100% (2)

- Miriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"Document20 pagesMiriam Hansen's Introduction Kracauer's "Theory of Film"dbluherNo ratings yet

- On The Real and The Visible in Experimental Documentary FilmDocument12 pagesOn The Real and The Visible in Experimental Documentary FilmDaniel JewesburyNo ratings yet

- Cruel Creeds, Virtuous Violence - Jack David EllerDocument1,996 pagesCruel Creeds, Virtuous Violence - Jack David EllerAlma Slatkovic100% (1)

- 2020 - Rennebohm Wittgenstein (In October)Document30 pages2020 - Rennebohm Wittgenstein (In October)domlashNo ratings yet

- Screen - Volume 15 Issue 1Document128 pagesScreen - Volume 15 Issue 1krishnqais100% (1)

- Psychological Science Textbooks: TRIMESTER 3, 2020Document4 pagesPsychological Science Textbooks: TRIMESTER 3, 2020no_if0% (1)

- Ruby AnthrocinemaDocument14 pagesRuby Anthrocinemaklumer_xNo ratings yet

- 02 WholeDocument221 pages02 Wholekmvvinay100% (1)

- University of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlyDocument3 pagesUniversity of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlytaninaarucaNo ratings yet

- Dreaming of Cinema / Slow Cinema: Repositorium Für Die MedienwissenschaftDocument8 pagesDreaming of Cinema / Slow Cinema: Repositorium Für Die Medienwissenschaftalessandro regianiNo ratings yet

- Transworld Cinemas - David Martin-JonesDocument11 pagesTransworld Cinemas - David Martin-Jonesozen.ilkimmNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of the Film - An Analysis of Film TechniqueFrom EverandA Grammar of the Film - An Analysis of Film TechniqueRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Rosenstone Historical FilmDocument9 pagesRosenstone Historical FilmRohini SreekumarNo ratings yet

- Introduction Affecting A Knowledge of AntiquesDocument3 pagesIntroduction Affecting A Knowledge of AntiquesMichael Ramos-AraizagaNo ratings yet

- Between Stillness and Motion - Film, Photography, AlgorithmsDocument245 pagesBetween Stillness and Motion - Film, Photography, AlgorithmsMittsou100% (2)

- Filmtheoryfinalpart 2Document35 pagesFilmtheoryfinalpart 2AnikaNo ratings yet

- JURNAL JSTOR - Candelaria 1983 Social Equity in Film CriticismDocument8 pagesJURNAL JSTOR - Candelaria 1983 Social Equity in Film CriticismTaufik Hidayatullah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- New French Extremity - Taste of CinemaDocument15 pagesNew French Extremity - Taste of CinemawrittiNo ratings yet

- Imp Film TheoriesDocument5 pagesImp Film TheoriesPavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Film Theory RevisedDocument21 pagesFilm Theory RevisedAyoub Ait MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Film Theory RevisedDocument21 pagesFilm Theory RevisedAyoub Ait MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Theorizing The Moving ImageDocument45 pagesTheorizing The Moving Imagen1ck101100% (1)

- "The Avant-Garde and Its Imaginary," by Constance PenleyDocument32 pages"The Avant-Garde and Its Imaginary," by Constance PenleyChristoph CoxNo ratings yet

- 05 - Film Theory Form and FunctionDocument40 pages05 - Film Theory Form and Functiondie2300No ratings yet

- Ethos of CinemaDocument13 pagesEthos of CinemajosesbaptistaNo ratings yet

- Antropologie FilmDocument27 pagesAntropologie FilmAndreea HaşNo ratings yet

- Utopias Sci HubDocument18 pagesUtopias Sci HubDiego Mazacotte SNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Walley - The Material of Film and The Idea of Cinema. Contrasting Practices in Sixties and SeventiesDocument17 pagesJonathan Walley - The Material of Film and The Idea of Cinema. Contrasting Practices in Sixties and Seventiesdr_benway100% (1)

- Tie Xi QuDocument20 pagesTie Xi QuRick SanchezNo ratings yet

- The End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Document30 pagesThe End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Esteban BrenaNo ratings yet

- Exposing Yourself Reflexivity Anthropology and FilDocument30 pagesExposing Yourself Reflexivity Anthropology and FilArtoria RenNo ratings yet

- Film Studies Critical Approaches IntroductionDocument8 pagesFilm Studies Critical Approaches IntroductionPaula_LobNo ratings yet

- Documentary - History - DN10 - Sem3 - Manna Duk and Viktor Nemeth - 19DEC2022Document12 pagesDocumentary - History - DN10 - Sem3 - Manna Duk and Viktor Nemeth - 19DEC2022Viktor NemethNo ratings yet

- The Essay Film From Montaigne After MarkerDocument244 pagesThe Essay Film From Montaigne After Markeryu100% (1)

- Documentary and ReportDocument8 pagesDocumentary and ReportAna MartínezNo ratings yet

- Rodowick-Dr Strange MediaDocument10 pagesRodowick-Dr Strange MediaabsentkernelNo ratings yet

- Jargon and The Crisis of Readability: Methodology, Language, and The Future of Film HistoryDocument5 pagesJargon and The Crisis of Readability: Methodology, Language, and The Future of Film HistoryDimitrios LatsisNo ratings yet

- Project Elysium.Document39 pagesProject Elysium.Ramanand KNo ratings yet

- The Historical Film As Real History Robert A. RosenstoneDocument12 pagesThe Historical Film As Real History Robert A. RosenstoneLucy RoseNo ratings yet

- Meaning in Film, Domnica NastaDocument5 pagesMeaning in Film, Domnica NastaIulia BarbuNo ratings yet

- Round Table. Obsolescence and American Avant-Garde Film PDFDocument19 pagesRound Table. Obsolescence and American Avant-Garde Film PDFDaniel Tercer MundoNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism - Theory, Theorists and TextsDocument30 pagesPostmodernism - Theory, Theorists and TextsadanicNo ratings yet

- Cosmopolitanism and Animated Kinography in Persepolis and Sita Sings The BluesDocument12 pagesCosmopolitanism and Animated Kinography in Persepolis and Sita Sings The BluesxinyiNo ratings yet

- wk5 Contemporary Film TheoryDocument3 pageswk5 Contemporary Film TheoryrchelseaNo ratings yet

- Documentary: An Effective Tool For Representing Social IssuesDocument31 pagesDocumentary: An Effective Tool For Representing Social IssuesViktoria FomenkoNo ratings yet

- Film and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca FantoniDocument23 pagesFilm and History: A Very Long Engagement - Gianluca Fantonidanielson3336888100% (1)

- History in ImagesDocument14 pagesHistory in ImagesAli GençoğluNo ratings yet

- Var 1991 7 2 50Document18 pagesVar 1991 7 2 50Ashraya KhecaraNo ratings yet

- Cinema and IntermedialityDocument30 pagesCinema and IntermedialityLívia BertgesNo ratings yet

- Cinephile Vol4 BigDocument76 pagesCinephile Vol4 BiglafairyNo ratings yet

- The Parallax Effect: The Impact of Aboriginal Media On Ethnographic FilmDocument13 pagesThe Parallax Effect: The Impact of Aboriginal Media On Ethnographic FilmDavidNo ratings yet

- Cinematic ArtDocument11 pagesCinematic ArtSatyam SinghNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism Theories, Theorists and TextsDocument65 pagesPostmodernism Theories, Theorists and Textsraybloggs75% (4)

- Reform in China's New Cinema 1990Document29 pagesReform in China's New Cinema 1990Liam MilesNo ratings yet

- Toscano Reviews Ranciere On TarrDocument4 pagesToscano Reviews Ranciere On Tarrtomkazas4003No ratings yet

- Aesthetics Ethics CinemaDocument203 pagesAesthetics Ethics CinemaArturo Shoup100% (2)

- Film Theory and CausalityDocument6 pagesFilm Theory and CausalityJessica Fernanda Conejo MuñozNo ratings yet

- FilmTheoryTermPaper FaryalJogezaiDocument19 pagesFilmTheoryTermPaper FaryalJogezaiKim LegayaNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Faculty Brochure: Make Today MatterDocument20 pagesUndergraduate Faculty Brochure: Make Today Matterganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

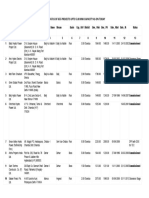

- List/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On TodayDocument45 pagesList/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On Todayganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Foldery Koji Shima (1) : HawkmenbluesDocument1 pageFoldery Koji Shima (1) : Hawkmenbluesganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Border News Media Coverage of Violence, Organized Crime, and The War On Drugs, and A Culture of LawfulnessDocument3 pagesBorder News Media Coverage of Violence, Organized Crime, and The War On Drugs, and A Culture of Lawfulnessganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Consumption of US Television and Films in Northeastern MexicoDocument23 pagesConsumption of US Television and Films in Northeastern Mexicoganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Theoretical Approaches and Methodological Strategies in Latin American Empirical Research On Television Audiences: 1992-2007Document30 pagesTheoretical Approaches and Methodological Strategies in Latin American Empirical Research On Television Audiences: 1992-2007ganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Public Policies and Research On Cultural Diversity and Television in MexicoDocument16 pagesPublic Policies and Research On Cultural Diversity and Television in Mexicoganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Nabokovs Time Doubling From The Gift To PDFDocument41 pagesNabokovs Time Doubling From The Gift To PDFganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Ruins of Doom Pages 1.1Document40 pagesRuins of Doom Pages 1.1Gin100% (1)

- Titanes Body Horror Love and TechnologyDocument9 pagesTitanes Body Horror Love and TechnologyCarlos Augusto AfonsoNo ratings yet

- 4049-Article Text-14612-1-10-20210226Document10 pages4049-Article Text-14612-1-10-20210226Marie Angel PantanoNo ratings yet

- Values Education Self Development PDF FreeDocument55 pagesValues Education Self Development PDF FreeHanima Macarambon100% (1)

- Math Lab Approach Lesson PDFDocument9 pagesMath Lab Approach Lesson PDFapi-381849962No ratings yet

- Meditation TechniquesDocument12 pagesMeditation Techniquesarjun454100% (1)

- Depth of Reflection Rubric - HandoutDocument2 pagesDepth of Reflection Rubric - HandoutIryna LiashenkoNo ratings yet

- Sleep Deeply Wake RefreshedDocument24 pagesSleep Deeply Wake RefreshedteommNo ratings yet

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 2 Lesson 7 Conditionals in Argumentative EssayDocument14 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 2 Lesson 7 Conditionals in Argumentative EssayChlea Marie Tañedo Abucejo80% (5)

- Research Paper On Labeling TheoryDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Labeling Theoryafnhdmovmtoddw100% (1)

- CowardDocument385 pagesCowarddanyjorge100% (3)

- Guruyoga Garabdorje PracticeDocument4 pagesGuruyoga Garabdorje PracticeTanya Marïa100% (1)

- The Sea AssignmentDocument3 pagesThe Sea AssignmentCristine G. LagangNo ratings yet

- Erpat-2 0Document43 pagesErpat-2 0fob offNo ratings yet

- Brand Awareness Effects On Consumer Decision Making For A Common, Repeat Purchase Product:: A ReplicationDocument12 pagesBrand Awareness Effects On Consumer Decision Making For A Common, Repeat Purchase Product:: A ReplicationSanjana SamarasingheNo ratings yet

- Course Overview and SyllabusDocument17 pagesCourse Overview and SyllabusJoelNo ratings yet

- Negotiation Skills: Asking For A Raise Selling PropertyDocument4 pagesNegotiation Skills: Asking For A Raise Selling PropertymanishNo ratings yet

- Justice Scales and Attorney Tales - The Lawful Symphony of Lawyers in SocietyDocument2 pagesJustice Scales and Attorney Tales - The Lawful Symphony of Lawyers in SocietyManha MukadamNo ratings yet

- Drug Addiction: Signs of Drug Use ConclusionDocument2 pagesDrug Addiction: Signs of Drug Use Conclusionjhoan eriquitaNo ratings yet

- Scary StoriesDocument15 pagesScary StoriesHannah MandrykNo ratings yet

- Flourish PDFDocument4 pagesFlourish PDFapi-372585795No ratings yet

- WorkbookEdition 7 The Scientific MethodDocument4 pagesWorkbookEdition 7 The Scientific MethodManalNo ratings yet

- Survey Questionnaire 1 - Student EngagementDocument2 pagesSurvey Questionnaire 1 - Student EngagementDAN MARK CAMINGAWANNo ratings yet

- Menangani Kelesuan Upaya Ibu Bapa (ParentalDocument19 pagesMenangani Kelesuan Upaya Ibu Bapa (ParentalTiey RaaNo ratings yet

- How To Ease Your AnxietyDocument6 pagesHow To Ease Your AnxietyManuel HerreraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Psychology Lecturer Sunaina MajeedDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Psychology Lecturer Sunaina MajeedMuhammad ShehzamNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Theories of MotivationDocument14 pagesContemporary Theories of MotivationSiddharth SetiaNo ratings yet

- Concept of RecreationDocument10 pagesConcept of RecreationTrixie MarananNo ratings yet