Professional Documents

Culture Documents

22 Emeg

Uploaded by

schauhan120 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views1 pagefgh

Original Title

22Emeg

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentfgh

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views1 page22 Emeg

Uploaded by

schauhan12fgh

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

etween 1967 and 1971, Prime Minister

Indira Gandhi came to obtain near-absolute control over the

government and the Indian National Congress party, as well as a huge majority in Parliament. The

first was achieved by concentrating the central government's power within the Prime Minister's

Secretariat, rather than the Cabinet, whose elected members she saw as a threat and distrusted.

For this, she relied on her principal secretary, P. N. Haksar, a central figure in Indira's inner circle of

advisors. Further, Haksar promoted the idea of a "committed bureaucracy" that required hitherto-

impartial government officials to be "committed" to the ideology of the ruling party of the day.

Within the Congress, Indira ruthlessly outmanoeuvred her rivals, forcing the party to split in 1969—

into the Congress (O) (comprising the old-guard known as the "Syndicate") and her Congress (R). A

majority of the All-India Congress Committee and Congress MPs sided with the prime minister.

Indira's party was of a different breed from the Congress of old, which had been a robust institution

with traditions of internal democracy. In the Congress (R), on the other hand, members quickly

realised that their progress within the ranks depended solely on their loyalty to Indira Gandhi and her

family, and ostentatious displays of sycophancy became routine. In the coming years, Indira's

influence was such that she could install hand-picked loyalists as chief ministers of states, rather

than their being elected by the Congress legislative party.

Indira's ascent was backed by her charismatic appeal among the masses that was aided by her

government's near-radical leftward turns. These included the July 1969 nationalisation of several

major banks and the September 1970 abolition of the privy purse; these changes were often done

suddenly, via ordinance, to the shock of her opponents. She had strong support in the

disadvantaged sections—the poor, Dalits, women and minorities. Indira was seen as "standing for

socialism in economics and secularism in matters of religion, as being pro-poor and for the

development of the nation as a whole." [4]

India, "The Emergency" refers to a 21-month period from 1975 to 1977 when Prime Minister Indira

Gandhi had a state of emergency declared across the country. Officially issued by

President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed under Article 352 of the Constitution because of the prevailing

"internal disturbance", the Emergency was in effect from 25 June 1975 until its withdrawal on 21

March 1977. The order bestowed upon the Prime Minister the authority to rule by decree, allowing

elections to be suspended and civil liberties to be curbed. For much of the Emergency, most of

Indira Gandhi's political opponents were imprisoned and the press was censored. Several

other human rights violations were reported from the time, including a mass forced

sterilization campaign spearheaded by Sanjay Gandhi, the Prime Minister's son. The Emergency is

one of the most controversial periods of independent India's history.

The final decision to impose an emergency was proposed by Indira Gandhi, agreed upon by

the president of India, and thereafter ratified by the cabinet and the parliament (from July to August

1975), based on the rationale that there were imminent internal and external threats to the Indian

state.[1][2]

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Sanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri CalligraphersDocument1 pageSanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri Calligraphersschauhan12No ratings yet

- Sanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri CalligraphersDocument1 pageSanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri Calligraphersschauhan12No ratings yet

- Sanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri CalligraphersDocument1 pageSanskrit Urdu Persian Greek Latin Arabic Kashmiri Calligraphersschauhan12No ratings yet

- Indira Gandhi's consolidation of power through constitutional amendments and the EmergencyDocument2 pagesIndira Gandhi's consolidation of power through constitutional amendments and the Emergencyschauhan12No ratings yet

- Abu'l-Fath Jalal-Ud-Din Muhammad AkbarDocument1 pageAbu'l-Fath Jalal-Ud-Din Muhammad Akbarschauhan12No ratings yet

- Sacred Games (TV Series)Document3 pagesSacred Games (TV Series)schauhan12100% (1)

- State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain: See AlsoDocument2 pagesState of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain: See Alsoschauhan12No ratings yet

- 1 AkbarDocument1 page1 Akbarschauhan12No ratings yet

- Dynamic Load Test: Motion or Acceleration TransducerDocument2 pagesDynamic Load Test: Motion or Acceleration Transducerschauhan12No ratings yet

- Abu'l-Fath Jalal-Ud-Din Muhammad AkbarDocument1 pageAbu'l-Fath Jalal-Ud-Din Muhammad Akbarschauhan12No ratings yet

- Modern HumansDocument1 pageModern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- World War OneDocument8 pagesWorld War Oneschauhan12No ratings yet

- Modern HumansDocument1 pageModern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- EmegDocument1 pageEmegschauhan12No ratings yet

- Sacred GamesDocument4 pagesSacred Gamesschauhan120% (1)

- Modern HumansDocument1 pageModern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- Modern HumansDocument1 pageModern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- World War OneDocument7 pagesWorld War Oneschauhan12No ratings yet

- Anatomically Modern HumansDocument1 pageAnatomically Modern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- Anatomically Modern HumansDocument1 pageAnatomically Modern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- YamunaDocument1 pageYamunaschauhan12No ratings yet

- World War OneDocument6 pagesWorld War Oneschauhan12No ratings yet

- World War OneDocument7 pagesWorld War Oneschauhan12No ratings yet

- Anatomically Modern HumansDocument1 pageAnatomically Modern Humansschauhan12No ratings yet

- Arms Race: SMS RheinlandDocument5 pagesArms Race: SMS Rheinlandschauhan12No ratings yet

- YamunaDocument1 pageYamunaschauhan12No ratings yet

- Taj Mahal: Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan's Mausoleum for his WifeDocument1 pageTaj Mahal: Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan's Mausoleum for his Wifeschauhan12No ratings yet

- Carefully Managed Grassy AreasDocument1 pageCarefully Managed Grassy Areasschauhan12No ratings yet

- "World War One", "Great War", and "WW1" Redirect Here. For Other Uses, See,, andDocument5 pages"World War One", "Great War", and "WW1" Redirect Here. For Other Uses, See,, andschauhan12No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Basic Legal and Judicial EthicsDocument1 pageBasic Legal and Judicial EthicsAnton ArponNo ratings yet

- Martinez Vs TanDocument3 pagesMartinez Vs TanGlenda Mae GemalNo ratings yet

- 48.phil Scout Vs SecretaryDocument2 pages48.phil Scout Vs SecretaryRey David LimNo ratings yet

- Prerna Arora BUS 261 Assignment 6Document8 pagesPrerna Arora BUS 261 Assignment 6Prerna AroraNo ratings yet

- The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005: Fundamental Changes Done in 1956 Act The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005Document28 pagesThe Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005: Fundamental Changes Done in 1956 Act The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005AMARNATHNo ratings yet

- Right To Property and Land Reforms 113Document11 pagesRight To Property and Land Reforms 113Syed Mohammad Aamir AliNo ratings yet

- Eagles Nest Outfitters v. Harden - ComplaintDocument31 pagesEagles Nest Outfitters v. Harden - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- (Https://parivahan - Gov.in/parivahan) Government of India: Ministry of Road Transport & HighwaysDocument2 pages(Https://parivahan - Gov.in/parivahan) Government of India: Ministry of Road Transport & HighwaysmuruguandcoNo ratings yet

- Past Exam Papers - FeminismDocument9 pagesPast Exam Papers - FeminismUdara SoysaNo ratings yet

- 317 - Lorenzo V NicolasDocument1 page317 - Lorenzo V NicolasThird Villarey100% (1)

- Brief Summary of Eric Shirt Vs Saddle Lake Cree Nation T-978-16Document2 pagesBrief Summary of Eric Shirt Vs Saddle Lake Cree Nation T-978-16Shannon M HouleNo ratings yet

- Ipr PDFDocument16 pagesIpr PDFUmar AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Sueno Vs LANDbankDocument6 pagesSueno Vs LANDbankRenz Jaztine Alcazar100% (1)

- Land Scams Involving The Power of Attorney in Land Dealings in MalaysiaDocument11 pagesLand Scams Involving The Power of Attorney in Land Dealings in MalaysiaANITH HUMAIRA MOHD KORDINo ratings yet

- Jacinto and Manotok CaseDocument6 pagesJacinto and Manotok CaseCarlos JamesNo ratings yet

- XXX HO#31 - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesDocument8 pagesXXX HO#31 - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesperlitainocencioNo ratings yet

- StatusOutcome 28 August 2019 PDFDocument5 pagesStatusOutcome 28 August 2019 PDFLiviu Baronei100% (1)

- 10 Batch4 Robinson Vs VillafuerteDocument2 pages10 Batch4 Robinson Vs VillafuerteLex D. Tabilog100% (3)

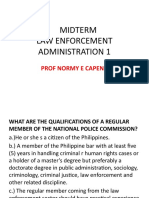

- Midterm Law Enforcement Administration 1: Prof Normy E CapenaDocument15 pagesMidterm Law Enforcement Administration 1: Prof Normy E CapenaPaolo VariasNo ratings yet

- Proquest Dissertations and Theses 2002 Rilm Abstracts of Music LiteratureDocument117 pagesProquest Dissertations and Theses 2002 Rilm Abstracts of Music LiteratureBrenton OffenbackNo ratings yet

- Guide to Effective Employee CounselingDocument29 pagesGuide to Effective Employee CounselingEmy Rose N. DiosanaNo ratings yet

- IPR BitsDocument2 pagesIPR BitsAnuNo ratings yet

- LLB Exam TimetableDocument17 pagesLLB Exam TimetableshamimNo ratings yet

- Corrigan v. Liberty Life Assurance Company of Boston Et Al - Document No. 2Document3 pagesCorrigan v. Liberty Life Assurance Company of Boston Et Al - Document No. 2Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Strack v. Frey - Document No. 33Document28 pagesStrack v. Frey - Document No. 33Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Land Dispute Case Decided in Favor of HeirsDocument15 pagesLand Dispute Case Decided in Favor of HeirsJosephine Redulla LogroñoNo ratings yet

- Excessive Bail Ruling OverturnedDocument18 pagesExcessive Bail Ruling OverturnedCaleb Josh PacanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment ContractDocument3 pagesAssignment ContractDavid DameronNo ratings yet

- 2018-01-26 Declaration of Attorneys For FaZe BanksDocument7 pages2018-01-26 Declaration of Attorneys For FaZe BanksDerrick M. KingNo ratings yet

- Taxation of Partnership FirmsDocument2 pagesTaxation of Partnership FirmsNaushad RahimNo ratings yet